1. Introduction

Research on generations has been around for some time. Mannheim’s [

1] seminal work in this area suggests that generations contain two essential components: a common location in a historic time period and a

distinct consciousness that is the result of important events of that time. Mannheim’s work predates but is reflected in, commonly used conceptualizations of generations based on age, such as baby boomers, Generation X, etc. These conceptualizations have their roots in the generational cohort theory, developed by Inglehart [

2] and later made popular by Strauss et al. [

3]. Strauss, Strauss and Howe [

3] defined a generation as: “a special cohort-group whose length approximately matches that of a basic phase of life, or about twenty-two years’’ (p. 34). Later, Kupperschmidt [

4] added a developmental and cultural aspect to the definition: “an identifiable group that shares birth years, age, location, and significant life events at critical developmental stages’’ (p. 66). The principle behind the concept of generations is that individuals are influenced by historical events and cultural phenomena that occur during key developmental stages typically late childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood [

5]. While there is general consistency across generations’ conceptualizations on birth years, development and culture, there is substantial variance in exactly when each generation starts and ends. For example, the baby Boom generation, about which there seems to be the most agreement on start and end dates, has starting years ranging from 1943 to 1946 and ending years from 1960 to 1969. Generation X has starting years varying from 1961 to 1965 and continuing on to 1975 to 1981 [

5]. There is a similar pattern for the millennial generation or Gen Y.

Therefore, in the same vein, the millennial generation, or Generation Y, can be defined as individuals born during the last two decades of the twentieth century [

5,

6]. Since the popular press recognizes millennials as an emerging generational group in today’s global workforce, executives, policymakers and academics have committed ample resources to understand them at work [

7]. As a result, the last two decades have seen a rapid increase in the number of research articles exploring the millennial generation at work. Former research mostly studied the previously predominant generations in the workplace i.e., baby boomers and Generation X [

4,

8]. Research on millennials at work dates from the beginning of the 2000s, though interpretation of the generation had begun earlier [

9]. In 2000, when the eldest of the millennials were about 20, a seminal book by Howe and Strauss [

10] described the millennial generation as special, vital, full of promise, sheltered, confident, team-oriented, achieving, pressured and conventional. The same year a book by Zemke et al. [

11] focused on managing and working with people from different generational groups (veterans, boomers, Generation Xers and nexters/millennials). Two years later, Lancaster and Stillman [

12] talked about the similarities and variations between different generations in the workplace, and [

13] explored the differences in work values between different generations at work (WWIIers, swingers, baby boomers, Generation Xers and millennials).

Since 2002, various empirical research studies to further understand millennials at work have reported contradictory findings [

14]. For example, work from Twenge [

15,

16,

17] identified millennials as narcissistic and with less concern for others, and hence labelled them as

Generation Me. Whereas other studies found millennials to have more of a sense of morality/ethics than previous generations [

18,

19]. Another debate surrounding millennials surrounds the question as to whether they are the first global generation. There is inadequate empirical evidence to prove or disprove the assertion that millennials are the first global generation [

20], with a generational consciousness that transcends national culture. Further, scholarship has yet to fully understand if millennials at a later stage in their career differ from those earlier in their careers [

21] and/or if millennials are a homogenous or heterogeneous group [

22]. Finally, while more recent and extensive media coverage, social media attention and popular culture references have made the term millennial a social meme [

23], academic research has become increasingly critical of generational labelling [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Therefore, to understand these debates, our bibliometric review examines the body of literature over the last 20 years, including how research studies on millennials at work relate to or build on each other. Further, various review studies and theoretical articles have been written to explore generations and generational differences [

30,

31,

32]. Other reviews have studied values, attitudes and behaviours of millennials in the workplace [

33,

34,

35,

36]. While these studies carried out extensive reviews of past literature on millennials at work, most of the review work was done almost a decade ago and, given the recent growth of literature on the subject, does not include the latest research trends. For this reason, we see the present need for another review paper to present the existing work and show how research has evolved and shaped other research on millennials at work over the past 20 years. We believe now is an important time to review the literature because the eldest millennials are now 38–40 years old and have entered key positions in organizations [

37]. In our review paper, we utilize bibliometric methods of citation, co-citation and bibliographic coupling analysis (utilizing VOSviewer and HistCite), as well as traditional content analysis. The methodology of our review differs from prior review studies, which have adopted more traditional review methods and which are susceptible to review authors’ specialization-in-the-field bias [

38,

39].

To fill in the gap in research on millennials at work, we used the following research questions to examine how millennials at work articles have evolved in the past 20 years:

(RQ1) Which mediums (articles, authors, journals, institutions and countries) are the most influential in the research on millennials at work?

(RQ2) What historic research streams emerge within the literature on millennials at work?

(RQ3) What are the (a) current research fronts and (b) future research questions?

Our study contributes to the literature on millennials at work in several ways. First, our citation analysis of the literature on millennials at work identifies key authors, articles, journals, institutions and countries to be considered for future research on the topic. Second, our co-citation analysis and bibliographic coupling, coupled with content analysis, extend earlier reviews by identifying the core structure of research on the topic in the past 20 years, identifying the underlying historic research streams, the current research fronts, a profile of millennials (categorized in terms of work, personal and psychological values, traits and attitudes) and future research questions. Finally, we present implications for HRM practice and research. This X-ray of research may help researchers and practitioners to circumnavigate the different avenues for their future research and help them in identifying possible ideas and interventions that deserve more attention. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes bibliometric techniques and their suitability for our study,

Section 3 describes our data search and analysis strategy,

Section 4 presents the results,

Section 5 provides discussion and implications, and

Section 6 discusses the limitations of the study and concludes.

3. Methods

On 30 December 2020, we searched the WOS database for publications over the period 2000–2020 with the term Millennial*, generation y*, and gen y* in their title or topic. The WOS database was preferred over other databases, such as Google Scholar or Scopus, because many notable bibliometric reviews have used this database before [

42,

43,

44,

46,

47]. Further, recent reviews comparing different publication databases show that WOS has the top-tier quality of publications, is designed for citation analysis, and is thus compatible with most citation analysis tools [

48]. The year 2000 was chosen as a benchmark year because millennials may have been nearing entry into the workforce [

33]. Additionally, as indicated in the introduction in the year 2000, two seminal books on millennials were published. The initial search revealed 15,037 records which were refined further by WOS categories (Psychology Multidisciplinary OR Business OR Management OR Psychology Social OR Public Administration OR Psychology Applied OR Business Finance), resulting in 1542 relevant publications. These categories were chosen because of the organizational focus of our research. We only included articles and review articles, written in English.

The records were then downloaded and imported into the VOSviewer to collect the keywords of these 1542 articles (all keywords with five or more occurrences) to assess the content of the research on millennials [

45]. VOSviewer can classify those keywords into different clusters: those located near each other depict high co-occurrence in articles, and those further apart demonstrate low co-occurrence. Each keyword cluster represents a research stream on millennials [

42]. We identified two distinct research clusters: millennials as consumers, and millennials at work.

Our focus was on the latter, millennials at work, stream of research. Therefore, we further refined our WOS search with the frequently co-occurring keywords identified from the keyword co-occurrence analysis (within the millennials at work cluster). The keywords were: cohort*, generational difference*, work*, value*, work value*, workplace*, attitudes*, performance*, behavior*, satisfaction*, commitment*, motivation*, career*, psychological contract*, turnover*, leadership*, recruitment*, age*, personality*, business ethic*, corporate social responsibility*, ethic*, and sustainability*. The search yielded 305 records. The records were then imported again in VOS viewer to perform a co-citation analysis with cited references as our unit of analysis. The purpose was to also include external WOS references that shared a high number of co-citations with our sample articles (five or more citations), in our final sample [

49]. The procedure resulted in an additional 72 articles and so we reached a final sample of 377 articles on millennials at work.

Figure 1 depicts a flow diagram of the search strategy.

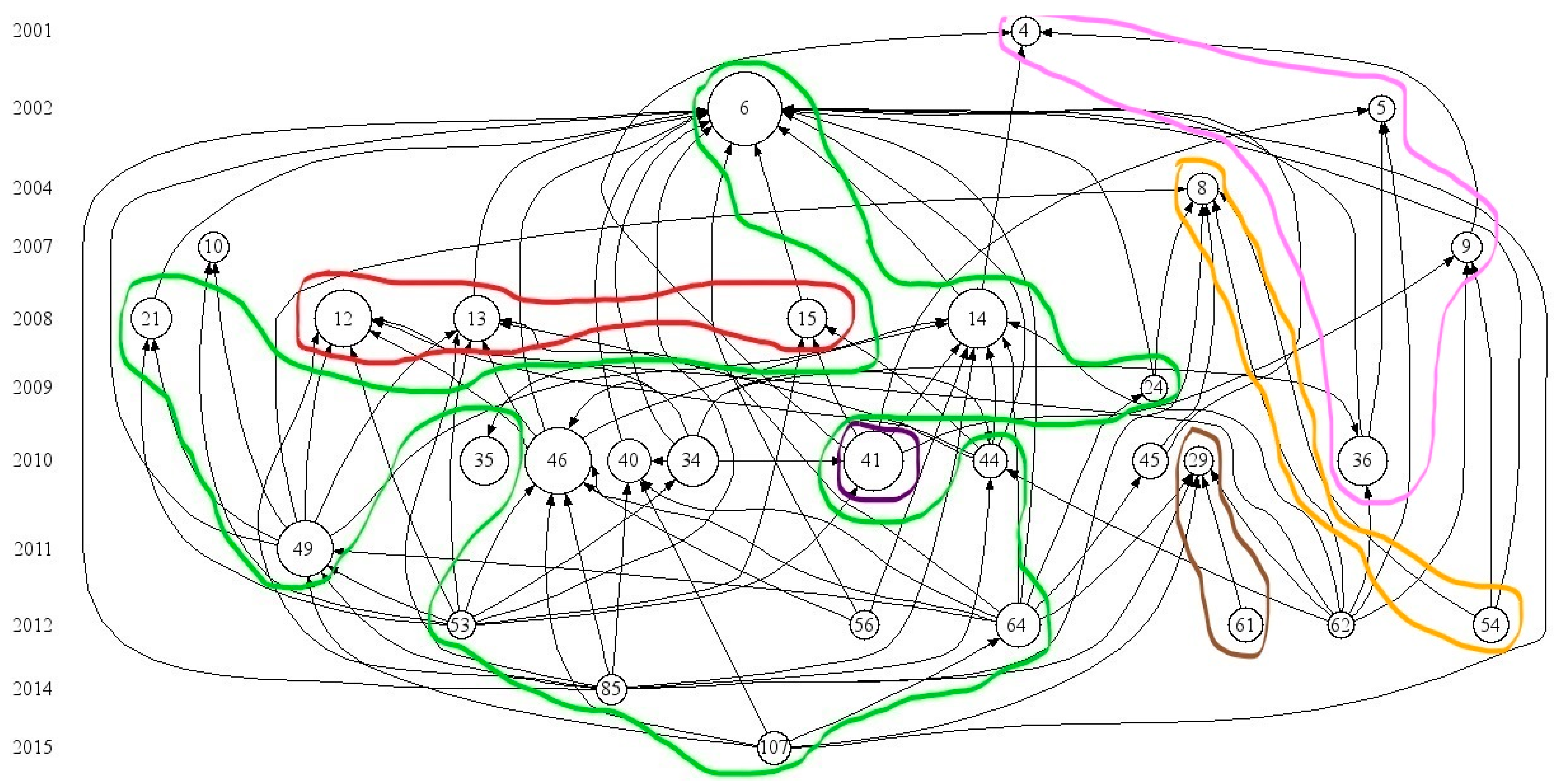

The 377 records were then imported into HistCite for further analysis of influential mediums (authors, articles, journals, institutions, and countries) to address RQ1. In order to answer RQ2, we first used HistCite to visualize the co-citation/historiographic map based on TLC (number of times a paper is cited by others within our retrieved set of 377 papers). To get an interpretable co-citation map, we only considered the articles cited ten or more times locally (TLC ≥ 10). Previous studies have used similar limits to show the most important citation links within the collection, simultaneously maintaining both the good readability of the graph and an understanding of the research streams emerging from the most important articles [

42,

50]. Co-citation/historiographic maps depict how articles are co-cited reciprocally over time (relationship between cited documents) and helps in identifying the historic core, or skeleton, of research [

43,

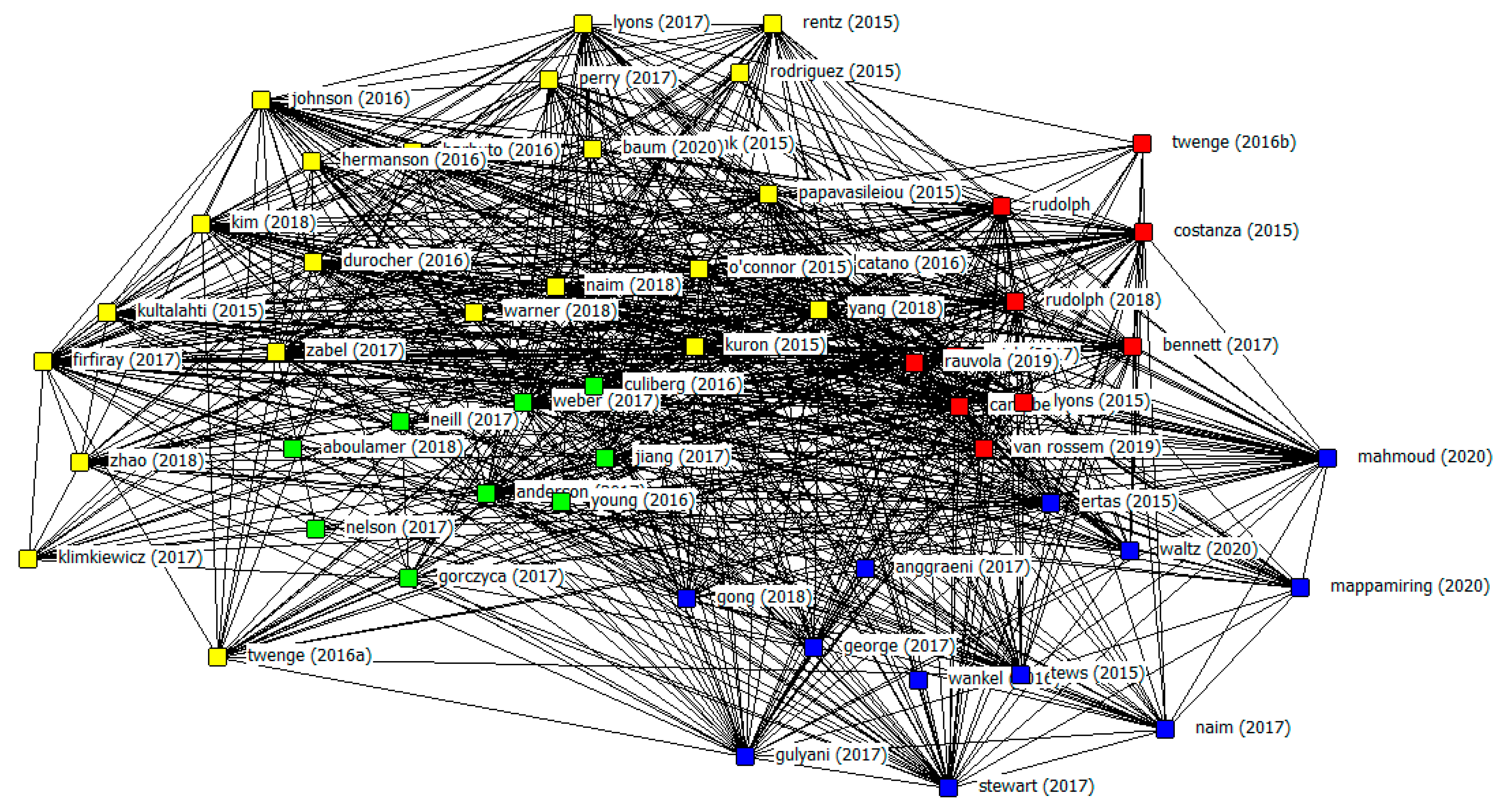

50]. To answer RQ3(a), we performed bibliographic coupling of articles published from 2015 to 2020. Bibliographic coupling reveals the network of citing documents and helps in identifying the current research fronts because it traces more recent publications, independently of the frequency with which they have been cited [

38,

46].

We analysed the content of the articles using a concept matrix developed in MS Excel [

44,

51]. This matrix consists of node id, authors, article title, publication year, journal, data and sample, context, methodology, theory, type of study, key findings and recommendations for future research columns. Using content analysis of latest and top-journal articles we answered RQ3(b) by obtaining the future research questions from articles’ recommendations for future research.

5. Discussion

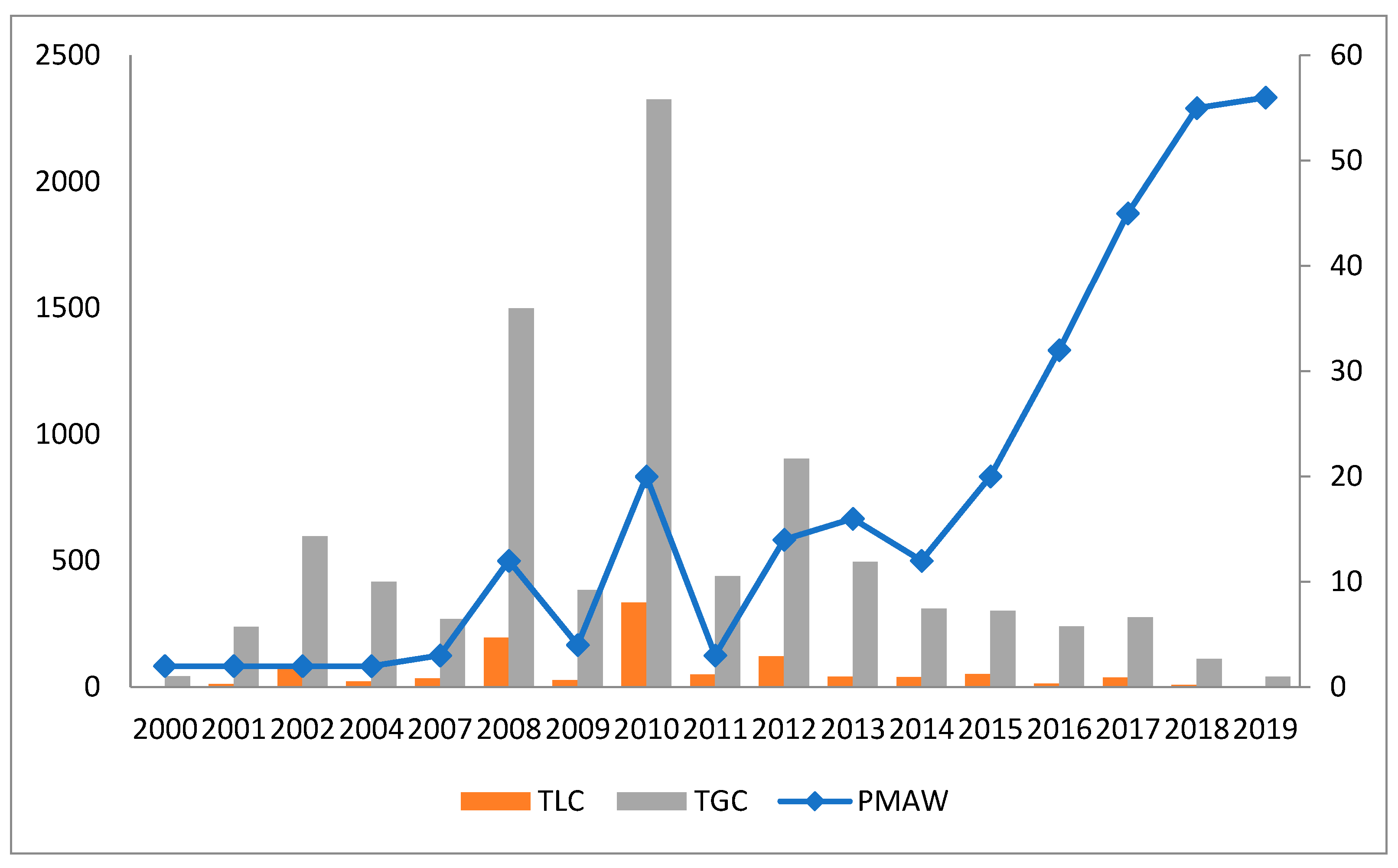

Our article contributes to the understanding of literature on millennials at work by reviewing the literature produced over the past 20 years. This growing body of literature (see

Figure 2) is of increasing importance now that the millennial generation has become a substantial and integral part of the workforce and its management.

We utilized bibliometric methods of citation, co-citation and bibliographic coupling analysis, as well as content analysis to answer three research questions. For RQ1 we identified the most important articles, authors, journals, institutions and countries in terms of the number of publications and citations (see

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4).

Table 1 and

Table 2 provide detailed references that the academic community can utilize to study millennials at work. The articles by Twenge, Campbell, Hoffman and Lance [

52] and Smola and Sutton [

13] are the two most influential articles in terms of TGC/t (see

Table 1). The article with the highest LCSe is a millennial-centred article exploring intragenerational differences (see Stream 5) by Ng, Schweitzer and Lyons [

54] (

Table 2). This further indicates that millennials (and other generations) may be conceptualized as fuzzy social constructs [

26,

97,

101] with individuals differing more from each other within a certain age bracket than across age brackets.

Figure 2 shows several peaks in P

MAW, TLC and TGC that we think might be because of the special issues published by the

Journal of Managerial Psychology (JMP) (‘Generational differences at work’, 2008), the

Journal of Business and Psychology (JBP) (‘Millennials and the World of Work’, 2010) and the

Journal of Social Psychology (JSP) (‘Millennials in the Workplace’, 2019). In addition,

Table 3 shows that, interestingly, no journal apart from

JMP and

JBP seems to be dominating research on millennials at work and it is surprising to see little research published in top-tiered journals such as, for example, the

Journal of Management (JOM) (P

MAW = 1). Even more surprising, another top-tiered journal, the

Journal of Organizational Behavior (JOB), has published very little research on millennials at work, though the seminal article by Smola and Sutton [

13] was published in

JOB.

Figure 3 confirms our observation. This information may be useful for journal editors who want to encourage research on the millennial generation. The findings related to influential institutions and countries reveal that most of the research on millennials at work has originated from the U.S., which is well ahead of other countries. (A detailed table of influential institutions ranked by P

MAW and citation metrics is available upon request.) This is understandable because the concept of millennials/Generation Y has originated from the West. Researchers from other countries may find this information useful and may be motivated to study the young generations within their cultural context. For RQ2 and RQ3(a), using co-citation and bibliographic coupling, we identified six distinct but interrelated research streams (the historic core of research) and four research fronts (current research) (see

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

Lastly, from the review and analysis of the literature, we derived a profile of millennials and future research questions (RQ3(b),

Table 5 and

Table 6), which may shape the development of generational research. In particular, we believe that the questions put forth in the Generations: Critical perspectives front may be the most important ones to consider by future researchers because criticism of the concept of generations seems to have been reaching a fever pitch lately—so much so that there have even been calls for abandoning generational research completely [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], though newer ways have been suggested to approach the concept of generations [

94,

121]. In the following sub-sections, we expand our interpretations from the answers to RQ3(b), to present the implications for HRM practice and research.

5.1. Implications for HRM Practice

The popular presses’ continual portrayal of generational labels has also led the practitioner media to stereotype individuals within a category by assuming that all generational members possess the same traits, behaviours, and values [

22]. For example, Deloitte in their 2020 survey inform employers that environmental stewardship influences loyalty among millennial employees [

122]. However, an influential strand of academic research (Research front 4: Generations: Critical perspectives) argues there is no real basis in academic theory or evidence for distinct generational categories such as millennials [

94]. However, the pursuit of the mainstream, social and practitioner media seems to outweigh the evidence presented in academic research and employees are still commonly segmented into generational categories such as millennials, presenting the risk that HRM practices become biased by stereotypes. Nonetheless, HRM must seek to derive value from generational research which can help inform strategies for inclusion by providing a better understanding of the dimension of differences that drives diversity. A more flexible and inductive approach, as suggested by Parry and Urwin [

94], may be the way to go for HR professionals—an approach that need not associate specific characteristics to particular age groups, but which considers how any changes identified in generational categories can be accommodated to promote inclusion within organizations. As such, even among millennial workers, a one-size-fits-all approach to HR policies and programs may be inappropriate [

92]. Because there is very little research evidence to support the idea that a global millennial generation exists, multinational organizations may be advised to view their young workers as a heterogeneous group rather than as stereotypical ‘millennials’. Further, other demographic differences among millennials need to be identified. For example, HR managers seeking to attract millennial employees should be aware that female millennials may be more ethical than males [

22]. Further, organizations that have employed millennials at the start of their careers, may legitimately ask now whether these later-career millennials have grown up and settled down with time. Archival and retrospective data, if available to HRM, may be utilized to draw conclusions about them in the earlier stage of their life, or used to study variations within the millennial group based on the amount of work experience in order to be better informed [

21,

22].

5.2. Implications for HRM Research

Despite the academic criticism on generational research and labelling or categorization, academic research still seems to be investigating millennials and the upcoming generation, Generation Z, under their respective generational labels. To explain our point, we are informed by the WOS alert that, since our literature search on 30 December 2020, 194 articles on millennials have been published as of 7 July 2022 (Results available upon request.). This may be an indication that research scholarship may not be willing to wholly desert generational research as suggested by some commentators [

26,

28]. The same commentators, however, also note that generations are ubiquitous due to their popular acceptance, but that alternate explanations need to be explored. Thus, we believe that future research hinges on the exploration of critical perspective and ways forward as suggested by, for example, Parry and Urwin [

94]. According to Parry and Urwin [

94], focusing on the year of birth and the continued use of generational labels or categories, such as millennials, is problematic because it prevents researchers from understanding the impact of contextual changes on the workforce and from considering meaningful individual differences in employees. They suggest that the longitudinal research on generations should adopt a more inductive and flexible approach that does not have to rely on a strict identification and disentanglement of age, period and cohort effects. Their approach proposes the identification of a dynamic that may be generational in nature but does not accept the presumption that such dynamics present only as categorical changes. Thus, in referring to Parry and Urwin, generational research can be retained in HRM. However, according to their approach and in the call for further research from Lyons and Schweitzer [

23] and Weber and Urick [

22], HRM researchers may ask and explore the question as to whether the generational label millennial is even valid, and whether all millennials are the same. Thus, investigators may shift away from a sole focus on year of birth and investigate other contextual drivers of the difference in attitudes, such as the role of location, gender and ethnic group. To explore the contextual drivers, robust conceptualizations, such as the notion of social location and construction, generational identities, collective memories and lifespan perspectives [

1,

26,

61], need to be incorporated.

Further, while exploring the ethical profile of millennials [

73], millennials at work can, for future research, be linked to UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). For example, future research may explore how millennials at work can contribute to sustainable economic growth through innovative business models, entrepreneurship, and employment opportunities (Goal 8: decent work and economic growth); how they view gender equality in the workplace, drive changes in policies and practices, and what more needs to be done to achieve gender balance (Goal 5: Gender equality); how they are changing consumer behaviour and pushing for more sustainable practices in businesses, such as reducing waste, promoting recycling, and using renewable resources (Goal 12: Responsible consumption and production); how they are addressing climate change through their work, for example, by promoting sustainable energy, reducing carbon emissions, and advocating for climate-friendly policies; and how they view education and contribute to the promotion of access to quality education in their workplaces and communities (Goal 4: Quality education).

Finally, in terms of methodology, prior review studies, both those that have explored generations/generational differences and those that have centred on millennials, were traditional reviews. Though traditional reviews benefit from the authors’ expertise in the field, they are also vulnerable to review authors’ specialization-in-the-field biases [

38,

39]. While few review studies were meta-analyses, they were narrower in scope. For example, Twenge [

30] used four time-lagged studies and Costanza, Badger, Fraser, Severt and Gade [

5] examined 20 studies to explore intergenerational differences in work attitudes. Our bibliometric review study comprehensively explores the body of literature on millennials at work over the last 20 years and offers context and placement in the literature for prior studies [

38]. To the best of our knowledge, no previous review study has performed a bibliometric analysis of literature on millennials at work. Using bibliometrics, our study, therefore, seeks to provide a quick reference guide for researchers interested in research on millennials at work by identifying the historic core structure of research, the current research fronts and subsequently identifying the key authors, articles, journals, institutions and countries and recommending questions to be considered for future research.