Learning from the Future of Kuwait: Scenarios as a Learning Tool to Build Consensus for Actions Needed to Realize Vision 2035

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Vision 2035 for the State of Kuwait

1.2. Problem Statement and Significance

- The unfinanced budget deficit;

- A waning infrastructure;

- Over-reliance on the oil sector;

- Limited linkage between the Kuwait Master Plan and the Development Plan;

- The weak role of the private sector in development;

- A poor track record of attracting Direct Foreign Investment (DFI).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Introduction to Royal Dutch Shell Scenarios

2.2. Input Variables

- (a)

- Which values, principles, incentives, and punishments does the national state stand for and uphold?

- (b)

- What role and format should be in place for general voters’ decisions to influence society?

- (c)

- Which forms and functions of governmental bureaucracies deliver the greatest good for the greatest number of people?

- Economic and social values;

- The state of relative safety in society;

- Fairness, transparency, and equality;

- The quality and affordability of healthcare and education;

- The merit-based upward mobility of individuals, groups, and regions;

- The competitive advance of nations in comparison to other nations;

- Quality of life according to the UNDP Happiness Index [49].

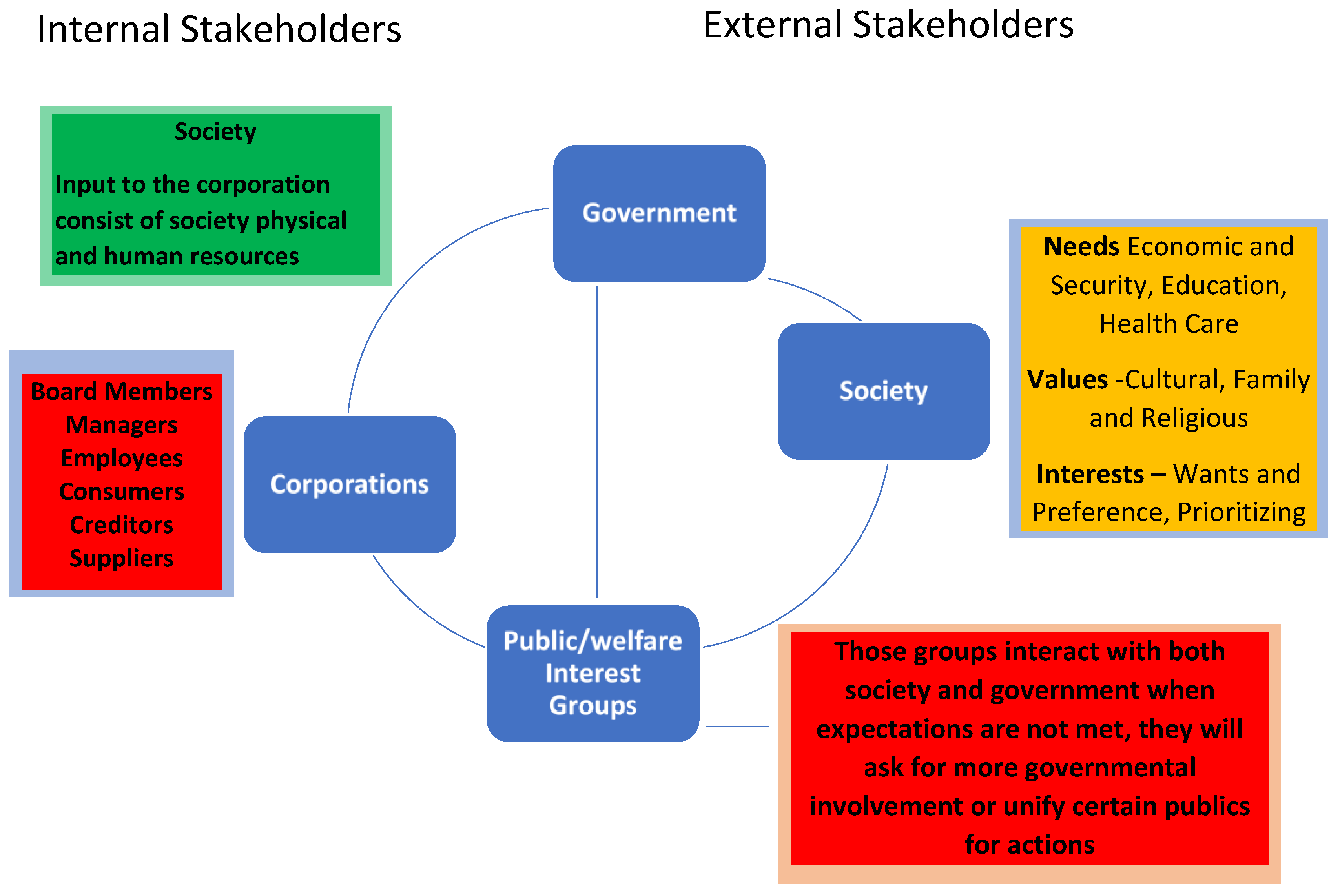

- internal stakeholders with societal input into the productive forces that form corporations, such as the employees, customers, suppliers, shareholders, and creditors, and members of the corporate structure that make decisions that affect the output and impact that corporations make on society [50]; and

- external stakeholders from various forms of governments and governmental bureaucracies and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and special interest groups that can help companies in terms of giving advice, opening doors to new opportunities, granting soft loans and finance, and providing protection against unfair competition, but can also restrict companies by providing inefficient, timely, and complicated procedures and high taxation and limiting advancement, often in order to protect environments, health and safety, or workers and the public, as well as to ensure a fair and efficient competitive environment [51].

2.3. Sources of Economic Growth

- A surge in aggregate demand, meaning a growth in domestic consumption, increase in governmental spending, and company domestic expansion, often driven by population growth via bringing in foreign labour;

- A rise in aggregated supply, and increased productive capacity through better use of existing capital goods and machinery, which will in turn increase unit labour productivity [53];

- The discovery or amplified utilization of natural resources such as oil and gas, hydro, geothermal, wind and solar power, fisheries, minerals, and forestry exploitation;

- Innovation and entrepreneurship activities, such as growth in new product and service creation, commercialization, development, and implementation—especially if these new endeavours will lead to growth in exports.

3. The Process of Data Integration: A Critical Interpretive Synthesis

3.1. Steps in Building a Scenario

- A comprehensive list of drivers is agreed upon, as are economic and social variables to be used in the creative scenario-building process.

- The interrelationship among the drivers and the variables must be analyzed to understand their causal connection to each other [33].

- Defining dimensions that embrace the areas of greatest uncertainty, spread over a broad but plausible range, to ensure the width and scope of the study.

- Criteria are established to select three to five phenomena (pasts) for the scenario formation and ensure that they all offer, within range, equally plausible future outcomes.

- Either a wide range of experts are gathered to devise the scenarios (the future forward approach) or adoptable historical developments (the future backward approach) are used.

- Different effects of some of the foreseeable future challenges are calculated, and sets of strategies are formulated either to counter the evolution or to advance it.

- These future scenarios are then presented in an eye-catching manner that creates conversation and rejoinder from the widespread collection of spectators, audience members, and readers, particularly the ones who are in positions to influence the real future outcomes.

- At the final stage, a consortium of specialists and opinion leaders is assembled in a discussion of which strategies, guidelines, and positive as well as punitive incentives would produce an “optimal” result that would generate the greatest good for the greatest number of citizens.

3.2. Selecting and Evolving the Scenario Drivers (Steps 1 and 2)

- future expectations and preferences regarding consumer confidence;

- market stability and price volatility;

- inward and outward perceptions of national competencies, and

- the general level of optimism, impacting present domestic spending, and building sustainable economic growth if these sentiments are based on solid foundations, or create short-term gains at the expense of long-term development if the thoughts are fabricated and illusionary.

3.3. Choose, Research, and Label the Scenario Projections (Steps 4–5)

3.3.1. Singapore’s Past: Sustainable Growth

- (a)

- The country’s strategic location, through which 40% of world trading routes pass, and an efficient and timely logistics infrastructure to take advantage of the location.

- (b)

- It actively attracts foreign investment and international talent through public and private invitations, low tax policies, and property and other rights protection.

- (c)

- Highly efficient, effective, and transparent governmental procedures and practices.

- (d)

- A stable political system and strong ties between the government and businesses by enforcing strict, transparent, and effective non-corruption measures via a highly efficient legal system.

- (e)

- The most progressive English-speaking education systems start in kindergarten and above. Education is a large sector with high quality standards, placing Singapore first according to the Human Capital Index. Robert Lucas from the University of Chicago states that human capital development, especially in natural science and technology, is the best indicator of future economic growth [67]. Singapore has been systematically among the top three for over three decades in the OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) competitions, which measure average scores in mathematics, science, and reading among the youth of every country [68].

- (f)

3.3.2. The Venezuela Story: Non-Sustainable Growth

3.3.3. The Lebanon Story

3.3.4. Labeling the Past for Future Forward Projection of Socio-Economy of Kuwait

3.4. Select Challenges for the Future (Step 6)

- The decline in the relative size of the workforce in the general population is due to longevity and falling childbirth rates per woman.

- The changing of worldwide competitive factors, which is frequently called the globalization phenomenon.

- The adaptation to new production and delivery technology, particularly atomization, such as self-service online sales of products and services, non-manned production and delivery, and enriched customer experiences with the use of Virtual and Augmented Reality (VR&AR) and Artificial Intelligence (AI), which can analyse and react to big data more accurately and effectively at a fraction of the time and cost compared to today’s business practices.

3.4.1. Ten Technology Trends Affecting Work in Near Future

- Process automation and virtualization (robots, automation, and 3D printing);

- Faster and greater machine-to-machine connectivity (decentralization over borders);

- Cloud computing (increased speed, reduced complexity, cost savings);

- Quantum computing (leap in speed of computer calculations for machine learning and artificial intelligence);

- Human Replacement Artificial Intelligence (service sector AI interfaces);

- AI-driven computer programming (for customization, speed, and simplicity);

- Trust architecture (block chain, biomarkers, wearable computer chips);

- The BIO revolution (DNA custom-made medicine, self-bio robots, life health data reporting);

- Next-gen materials (nano-technology-based shape/colour/form-shifting material);

- The Clean Tech Revolution (unit cost reduction in new renewable energy applications).

3.4.2. Industries That Will Be Most Affected by Technological Changes

- Healthcare (pharmaceutical and healthcare providers);

- Mobility sectors (transportation, logistics, and the automotive industry);

- The Industry 4.0 sector (advanced industries, chemicals, and electronics);

- The enablers sector (information gathering, distribution, and telecommunications).

3.4.3. Demographic Affecting the Work Place in KUWAIT

3.4.4. Seven Strategies to Bridge the Upcoming Labour Shortage Gap to Ensure Sustainable Development

- Longer work life and the postponement of retirement considering a longer life expectancy. Retirement at the age of 60 is available to many who are working in the public sector, and several restrictions apply to renewing the residencies of expats over sixty, especially for those who do not hold a university degree [98].

- Employment of foreign labour where specialized skills are in need or for 3D (dirty, difficult or demeaning) work usually not sought by Kuwait nationals, where it is dirty, difficult, and demeaning.

- Exporting service and production work in the form of outsourcing contracts, usually for call centres or digital services on the service side, and subcontracting production of goods in low-wage workplaces in Southeast Asia.

- Employing more Kuwaiti women as a result of the lowering birth rate from 4 children per woman 20 years ago to 2 children per woman in 2022. Women will be increasingly represented in the workplace, especially in light of the fact that as high as 65% of university students in Kuwait are women as of 2022. Currently, only 57% of women are represented in the workplace, compared to 85% of men, and women only enjoy around 56% of men’s salaries. Incentive programs with quota systems for either gender might lower this gap [99,100,101].

- Supporting female-owned entrepreneurship. It is evident from the data that female entrepreneurship is one of the most promising opportunities with which to grow the Kuwaiti economy but is exploited the least. Women in the Gulf Cooperation Countries (GCC) complain that external investment and department service are very much restricted to female owned enterprises. In the Middle East and North Afrika (MENA) area, companies created by women raised only 1.3% of the $3.94 billion funded in 2022. Female-led enterprises create 78 cents for every dollar invested. Comparatively, male-founded firms only produce 31 cents. Investing in firms managed by women appears to be a financially and morally sound decision. Kuwait supports entrepreneurship and innovation mainly through the Kuwaiti Foundation for Scientific Advancement (KFAS) and affiliated institutions, as well as financial institutions such as the National Fund for Small and Medium Enterprise Development (National Fund) [102,103,104,105]. Some kind of quota system to ensure that either gender will achieve a certain minimum might be beneficial.

- Employing further automation, self-service through digitized technology, or robotics to diminish the need for repetitive work.

- Added social and financial incentives to increase childbirth through governmental and social programs that allow women to have prosperous careers while taking care of numerous children.

3.4.5. Governmental Response to Technology and Demographic Shifts

- Cutting public spending and decreasing social entitlements, which might result in some form of civil protest.

- Issuing local or foreign governmental loans, which will have future implications as they will have to be paid back with interest later but might have the immediate impact of increasing capital for public and private companies as well as weakening the local currency.

- Levying higher taxes for individuals and firms, which will have a negative impact on economic growth as less money will be available for domestic consumption.

4. Projects: The Three Future Scenarios Applied to the State of Kuwait (Step 7)

4.1. The Private-Led Sustainable Growth Scenario—Inspired by Singapore’s Past Development

4.2. Borrowing from the Future Generations—Inspired by Venezuela’s Past Development

4.3. Strategic Stagnation Scenario—Inspired by Lebanon’s Past Development

5. Discussion: Paint the Big Picture and Provoke an Informed Discussion and a Decision-Making Process (Step 8)

6. Limitations and Future Studies

7. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | Identify critical uncertainties: First, identify the main uncertainties that could affect the future of your organization or community/society. These uncertainties may be caused by political, economic, social, technological, or environmental elements. Shell typically focuses on two primary uncertainties, which allows for a manageable number of potential outcomes. |

| 2 | Create scenario axes: Using the identified uncertainties, develop axes that represent a spectrum of potential outcomes. Frequently, Shell’s scenarios employ two axes, yielding a matrix with four quadrants. Each quadrant represents a distinct prospective outcome. |

| 3 | Define scenario archetypes by developing a narrative for each quadrant that describes the primary characteristics, trends, and potential outcomes. These tales, or archetypes, will serve as the foundation for your scenarios. |

| 4 | Break each scenario archetype down into smaller, more manageable modules. This procedure involves identifying and organizing the essential elements or components of each archetype. By modularizing the scenarios, you can simply modify or alter them as new information becomes available, allowing for adaptable planning. |

| 5 | Incorporate external perspectives: To inform and refine your scenarios, consult a variety of external sources, including research papers, expert opinions, and data-driven analyses. This will ensure that your scenarios are grounded in reality and reflect the most current industry concepts. |

| 6 | Examine the potential impact of each scenario on your organization and/or community, including hazards, opportunities, and strategic responses. This information can assist with decision-making and long-term planning. |

| 7 | Communicate and engage: Share your scenarios with key stakeholders, including employees, partners, and customers, to facilitate discussions and gather feedback. This can help build a shared understanding of the possible futures and drive strategic alignment across the organization. |

| 8 | Monitor and revise: Continuously monitor the external environment and revise your scenarios as necessary. This will assist in keeping your planning pertinent and adaptable in the face of change. |

References

- Al Sager, N. (Ed.) Acquiring Modernity: Kuwait’s Modern Era between Memory and Forgetting; National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters: Kuwait City, Kuwait, 2014; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nakib, F.; Al-Nakib, F. Kuwait’s Modern Era Between Memory and Forgetting—Introduction to Acquiring Modernity Publication of the Kuwait. In Proceedings of the 14th International Architecture Exhibition, Venice, Italy, 7 June–23 November 2014; Available online: https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/31227/Understanding-Modernity-A-Review-of-the-Kuwait-Pavilion-at-the-Venice-Biennale (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Farid, A. Acquiring Modernity: Kuwait at the 14th International Architecture Exhibition. 2014. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20180224093441/http://gulfartguide.eu/essay/cultural-developments-in-kuwait/ (accessed on 27 May 2017).

- Sager, A.; Koch, C.; Tawfiq Ibrahim, H. (Eds.) The Kuwaiti Press Has Always Enjoyed a Level of Freedom Unparalleled in Any Other Arab Country. In Gulf Yearbook, 2006–2007; I.B. Tauris: London, UK, 2008; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian, H. Looking for Origins of Arab Modernism in Kuwait. 2015. Available online: https://hyperallergic.com/191773/looking-for-the-origins-of-arab-modernism-in-kuwait/ (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Gulf Art Guide. Cultural Developments in Kuwait. 2020. Available online: http://gulfartguide.eu/essay/cultural-developments-in-kuwait/ (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Gunter, B.; Dickson, R. News Media in the Arab World: A Study of 10 Arab and Muslim Countries; Bloombury, Academic: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, N. Kuwait: Building the Rule of Law; Human Rights in Kuwait: Hawally, Kuwait, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Helal, A. Kuwait’s Fiscal Crisis Requires Bold Reforms. 2018. Available online: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/kuwaits-fiscal-crisis-requires-bold-reforms/ (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Reuters UPDATE. Kuwait Closes 2019–2020 Fiscal Year with $18 Billion Deficit. Finance Ministry. 2020. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/kuwait-budget-idUSL8N2FF76K (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Moody’s Investor Service. Rating Action: Moody’s Affirms Kuwait A1 Rating: Maintaining Stable Outlook. 2022. Available online: www.cbk.gov.kw/en/images/moodys-may-2022-en-1_v00_tcm10-157955.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- Reuters. Kuwait Crown Prince Dissolves Parliament, Calls for Early Election. 2022. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/kuwait-crown-prince-dissolves-parliament-calls-early-general-election-2022-06-22/ (accessed on 26 June 2022).

- AP News 19 March 2023. Kuwait Court Annuls 2022 Parliamentary Election. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/kuwait-parliament-2022-election-overturned-b5b0fe0e7a1c4fc7018046c90ab0be66 (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- AlJazzera 19 September 2022 What to Know about Kuwait’s Parliamentary Elections. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/9/29/what-you-need-to-know-about-kuwaits-parliament-explainer (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Statista. Largest Sovereign Wealth Funds Worldwide as of December 2022, by Assets under Management. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/276617/sovereign-wealth-funds-worldwide-based-on-assets-under-management/#:~:text=The%20world’s%20largest%20sovereign%20wealth,reserves%20and%20established%20in%202007 (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Caravalho, A.; Youssef, J.; Ghosn, J.; Talih, L. Kuwait in Transitions: Towards Post Oil Economy. Report Commissioned by the Kuwait Investment Authority. 2017. Available online: https://www.ticg.com.kw/content/dam/oliver-wyman/ME/ticg/publications/TICG_PoV_Kuwait_In_Transition.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Walker, W.; Haasnoot, M.; Kwakkel, J. Adapt or Perish: A Review of Planning Approaches for Adaptation under Deep Uncertainty. Sustainability 2013, 5, 955–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Planning Commission (Republic of South Afrika), National Development Plan—Our Future. Make It Work 2012. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/Executive%20Summary-NDP%202030%20-%20Our%20future%20-%20make%20it%20work.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Choo, E.; Fergnani, A. The adoption and institutionalization of governmental foresight practices in Singapore. Foresight 2022, 24, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Future Economy (Singapoure) Report of the Committee on the Future Economy Pioneers of the Next Generation 2017. Available online: https://www.mti.gov.sg/Resources/publications/Report-of-the-Committee-on-the-Future-Economy (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Costanza, R.; Cork, S.; Atkins, P.; Bean, A.; Grigg, N.; Korb, E.; Logg-Scarvell, E.; Navis, R.; Patrick, K.; Diamond, A. Scenarios for Australia in 2050: A synthesis and proposed survey. J. Futures Stud. 2015, 19, 49–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gutsche, J.; Post-Pandemic Trends: Business Lessons from The Spanish Flu, Black Death and Roaring 20s. Keynote Speaker at Future Festival & The New Roaring 20s. Available online: https://www.FutureFestival.com (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- International Monetary Fund. IMF Videos—Annual Research Conference: Policy Panel—The Global Economy: Old Trade-Offs and New Challenges 2022. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/videos/view?vid=6315398884112 (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Kuwait National Development Plan 2020–2025. 2019. Available online: https://www.media.gov.kw/assets/img/Ommah22_Awareness/PDF/NewKuwait/Revised%20KNDP%20-%20EN.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Kuwait Competitiveness Index. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/kuwait/competitiveness-index (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- NBK Economic Update. Population and Labor. Available online: www.nbk.com.LF20221026E(1).pdf (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- World Factbook. 2022. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Countrymeter. Kuwait Population Clock. September 2022. Available online: www.countrymeters.info/en/Kuwait#Population_clock (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Macrotrends. Kuwaiti Fertility Rate 2021. Available online: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/KWT/kuwait/population (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- World Bank. Doing Business, Economic Profile—Kuwait 2022. Available online: https://archive.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/country/k/kuwait/KWT.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- UNDP 2023. Available online: https://www.undp.org (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- Kuwait Voluntary National Review 2019. Report on the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda to UN High Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/23384Kuwait_VNR_FINAL.PDF (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Fahey, L.; Randal, R. Learning from the Future: Competitive Foresight Scenarios; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ottesen, A. Three future scenarios for ten year economic and social development of small-island-state. In Proceedings of the Bi-Annual Conference of Accreditation Council for Business Schools and Programs in Wien, Vienna, Austria, 22–24 May 2009; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Pierre, W. Scenario: Shooting the Rapids. In Harvard Business Review; HBR: Brighton, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Pierre, W. Scenario: Uncharted Waters Ahead. In Harvard Business Review; HBR: Brighton, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, D. Public Choice III; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, G.; Hanel, P.; Johansen, M.; Maio, G. Mapping the Structure of Human Values through Conceptual Representations. Eur. J. Personal. 2019, 33, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwartney, J.; Richard, S.; Russel, S.; MacPherson, D. Private and Public Choices, 17th ed.; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, S.A. Conceptual Framework for Environmental Analysis of Social Issues and Evaluation of Business Response Pattern. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1975, 4, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, M.; Bryde, D.; Fearon, D.; Ochieng, E. Stakeholder Engagement: Achieving Sustainability in the Construction Sector. Sustainability 2013, 5, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R. On The Mechanics of Economic Development. J. Monet. Econ. 1988, 22, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, D.; Maier, A.; Aschilean, L.; Anastasiu, L.; Gavris, O. The Relationship between Innovation and Sustainability: A Bibliometric Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemad, H.; Gurau, G.; Leo-Paul, D. International entrepreneurship research agendas evolving: A longitudinal study using the Delphi method. J. Int. Entrep. 2022, 20, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcel, P.; Jurgen, R.; Stefan, S. How will last-mile delivery be shaped in 2040? A Delphi-based scenario study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 177, 121493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincă, G.; Dincă, S.M.; Negri, C.; Bărbuță, M. The Impact of Corruption and Rent-Seeking Behavior upon Economic Wealth in the European Union from a Public Choice Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santis, S. The Demographic and Economic Determinants of Financial Sustainability: An Analysis of Italian Local Governments. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, P.; Dicorato, S.L. Sustainable Development, Governance and Performance Measurement in Public Private Partnerships (PPPs): A Methodological Proposal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Helliwell, J. Happiness and Human Development UNDP Human Development Report Office 2014. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/happinessandhdpdf.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Uribe, D.; Ortiz-Marcos, I.; Uruburu, Á. What Is Going on with Stakeholder Theory in Project Management Literature? A Symbiotic Relationship for Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, M.; Hussain, H.I.; Kot, S.; Androniceanu, A. Role of Social and Technological Challenges in Achieving a Sustainable Competitive Advantage and Sustainable Business Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassif, V.; Ghobril, A.; Silva, N. Understanding the Entrepreneurial Process: A Dynamic Approach. Braz. Adm. Rev. 2010, 7, 213–226. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/j/bar/a/HNL87DDsFpXb3NzVCCN6W7C/?lang=en&format=pdf (accessed on 27 May 2021). [CrossRef]

- Osawa, Y.; Miyazaki, K. An empirical analysis of the valley of death: Large-scale R&D project performance in a Japanese diversified company. Asian J. Innov. 2011, 14, 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Solow, R.; Swan, T. A Contribution of Economic Growth. Q. J. Econ. 1956, 70, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vullo, C.; Morando, M.; Platania, S. Understanding the Entrepreneurial Process: A Literature Review. 2017. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322656454_UNDERSTANDING_THE_ENTREPRENEURIAL_PROCESS_A_LITERATURE_REVIEW (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Shell Energy Scenarios Till 2050. Available online: www.energyforum.fiu.edu/outlooks/shell_outlook.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Beery, J.; Eidinow, E.; Murphy, N.; Kahane, A. The Mont Fleur Scenarios: What will South Africa be like in the year 2002? Deep News 1992, 7, 1–22. Available online: https://exed.annenberg.usc.edu/sites/default/files/Mont-Fleur.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Huges, N.; A Historical Overview of Strategic Scenario Planning: A Joint Working Paper of the UKERC and the EON. UK/EPSRC Transition Pathways Project. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238111229_A_Historical_Overview_of_Strategic_Scenario_Planning_A_Joint_Working_Paper_of_the_UKERC_and_the_EONUKEPSRC_Transition_Pathways_Project (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Zhukovskiy, Y.L.; Batueva, D.E.; Buldysko, D.E.; Gil, B.; Valeriia Starshaia, V.V. Fossil Energy in the Framework of Sustainable Development: Analysis of Prospects and Development of Forecast Scenarios. Energies 2021, 14, 5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S. Life of Reason; Reprint from 1905; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- International Churchill Society. Winston Churchill Paraphrasing Harvard Philosophy Professor Georg Santaya in a Speech at the House of Commons. 1948. Available online: https://winstonchurchill.org/resources/in-the-media/churchill-in-the-news/folger-library-churchills-shakespeare/ (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Isabella, B.; Bianchi, G. Singapore: The Reasons Behind Its Economic Success. 2019. Available online: https://hospitalityinsights.ehl.edu/singapore-economic-success (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- National Public Radio. How Singapore Become One of the Richest Places on Earth. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2015/03/29/395811510/how-singapore-became-one-of-the-richest-places-on-earth (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore. Speech by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong at Official Opening of University Town. 2013. Available online: https://www.pmo.gov.sg/newsroom/speech-prime-minister-lee-hsien-loong-official-opening-university-town (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Fazio, D.S.; Modica, G. Historic Rural Landscapes: Sustainable Planning Strategies and Action Criteria. The Italian Experience in the Global and European Context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian Development Bank. The Singapore Economy: Success, Challenges, and Future Prospects; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund. Singapore’s Economic Success: Lessons for Developing Countries; International Monetary Fund: Bretton Woods, NH, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. PISA: Program for International Student Assessment. 2022. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/pisa (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Plastrik, P.; Cleveland, J. The City within a Garden. Next City Solution for Liberated Cities. 2019. Available online: https://nextcity.org/features/the-city-within-a-garden#:~:text=Singapore%2C%20a%20dense%20city%2Dnation,shapes%20with%20an%20altered%20perspective (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- World Economic Forum. Singapore: Anatomy of a Smart Nation; World Economic Forum: Colony, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Center for International Governance Innovation. Singapore’s Economic Miracle: Lessons for Policy Makers; Center for International Governance Innovation: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Singapore Management University. Singapore’s Economic Development: Retrospection and Reflections; Singapore Management University: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, L.Y. Fifty Years of development in the Singapore economy: An introductory review. Singap. Econ. Rev. 2015, 60, 1502002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, W.E.; Naya, S.; Meier, G.M. Asian Development: Economic Success and Policy Lessons; University of Wisconsin: Madison, WI, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh, T.; Vo, D.C.; Vo, A.T.; Nguyen, T.C. Foreign Direct Investment and Economic Growth in the Short Run and Long Run: Empirical Evidence from Developing Countries. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2019, 12, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, M. The Enduring Legacy: Oil, Culture and Society in Venezuela; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Salas, M. Venezuela: What Everyone Needs to Know; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, J.K. How Venezuela Fell from the Richest Country in South America into Crisis. The History Channel. 2019. Available online: https://www.history.com/news/venezuela-chavez-maduro-crisis (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- United States Institute of Peace. The Current Situation in Venezuela. USIP Fact Sheet. 2022. Available online: https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/02/current-situation-venezuela (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Huhn, S. Negotiating Resettlement in Venezuela after World War II. In Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung; GESIS-Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences: Mannheim, Germany, 2020; Volume 45, pp. 203–225. [Google Scholar]

- Kohan, A.; Rendon, M. From Crisis to Inclusion: The Story of Venezuela’s Women; Center for Strategic and International Studies: Wahington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, A.; Parks, B.; Russell, B.; Lin, J.J.; Walsh, K.; Solomon, K.; Zhang, S.; Elston, T.; Goodman, S. Banking on the Belt and Road: Insights from a New Global Dataset of 13,427 Chinese Development Projects; AidData at William & Mary: Williamsburg, VA, USA, 2021; pp. 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rosales, A. Resource nationalism: Historical contributions from Latin America. In Handbook of Economic Nationalism; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, H. Challenges in Future China-Latin America and the Caribbean (CLAC) Relations. In China’s Trade Policy in Latin America: Puzzles, Transformations and Impacts; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, B.; Rosales, A. The crisis in Venezuela. Eur. Rev. Lat. Am. Caribb. Stud. 2020, 109, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, R.; Landau, D. Abusive Constitutional Borrowing: A Reply to Commentators. Can. J. Comp. Contemp. Law 2021, 7, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Aljazeera News. Over 6.8 Million Have Left Venezuela Since 2014 and Exodus Grows. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/8/31/over-6-8-million-have-left-venezuela-since-2014-and-exodus-grows (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Krayem, H. The Lebanese Civil War and the Taif Agreement. American University of Beirut. 2012. Available online: https://libraries.aub.edu.lb/digital-collections/collection/borre-webarchive (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Qiblawi, T. Beirut Will Never Be the Same Again. 2020. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/08/05/middleeast/beirut-qiblawi-analysis-intl/index.html (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Trading Economics. Lebanon Government Debt to GDP. 2021. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/lebanon/government-debt-to-gdp#:~:text=Government%20Debt%20to%20GDP%20in%20Lebanon%20is%20expected%20to%20reach,macro%20models%20and%20analysts%20expectations (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- United Nation Human Right. Lebanon: UN Expert Warns of ‘Failing State’ Amid Widespread Poverty. 2022. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/05/lebanon-un-expert-warns-failing-state-amid-widespread-poverty (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- IMF. Lebanon: Staff Concluding Statement of the 2020 Article IV Mission. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/03/05/pr2063-lebanon-staff-concluding-statement-of-the-2020-article-iv-mission (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- World Bank Group. Lebanon Economic Monitor. World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/lebanon/publication/lebanon-economic-monitor-october-2021 (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- United Nations Development Programme. Lebanon’s Economic Crisis: Impacts and Ways Forward. 2020. Available online: https://www.lb.undp.org/content/lebanon/en/home/library/crisispreventionandrecovery/lebanons-economic-crisis-impacts-and-ways-forward.html (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- World Economic Forum. Top 10 Tech Trend That Will Shape the Coming Decade according to McKinsey. 2021. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/10/technology-trends-top-10-mckinsey/ (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Macrotrends Kuwait Fertility Rate 1950–2023. Available online: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/KWT/kuwait/fertility-rate (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- WorldData. Popuations Growth in Kuwait. Available online: https://www.worlddata.info/asia/kuwait/populationgrowth.php#:~:text=The%20average%20age%20in%20Kuwait,by%20%2D2.6%20percent%20per%20year (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Arabian Business. Kuwait Will Again Issue Work Visa to Expats over 60 Years Old. 2022. Available online: https://www.arabianbusiness.com/politics-economics/kuwait-will-again-issue-work-visas-to-expats-over-60-years-old (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- World Economic Forum. Global Gender Gap Report; World Economic Forum: Colony, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Human Development Reports. Kuwait. United Nations Development Programme. 2019. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2019 (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Human Development Report 2021/2022. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2021-22 (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Global Gender Gap Report 2021; World Economic Forum: Colony, Switzerland, 2022.

- Arab Times, Femail Student Take Majority at Kuwait University 2022. Available online: https://www.pressreader.com/kuwait/arab-times/20220109/282067690285786 (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Kuwait Foundation for Scientific Advancement -Who We Are. Available online: https://www.kfas.org/Organization/About-Us (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- National Fund for Small and Medium Enterprise Development. Available online: https://www.nationalfund.gov.kw/en/ (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Scott, R.E.; Choi, S.J.; Gulati, M. Anticipating Venezuela’s Debt Crisis: Hidden Holdouts and the Problem of Pricing Collective Action Clauses. BUL Rev. 2020, 100, 253. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, P. The Art of the Long View: Planning for the Future in an Uncertain World; Doubleday & Currency Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Shell Global. Shell Scenarios: An Exploration of the Future. 2013. Available online: https://www.shell.com/energy-and-innovation/the-energy-future/scenarios.html (accessed on 13 April 2023).

| Country | Venezuela Past Projection | Singapore Past Projection | Lebanon Past Projection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario Label | Borrowing from Future Generations | Private-Led Sustainable Economy | Strategic Stagnation |

| Financial Prudence | Least important | Most important | Somewhat important |

| Image Management | Most important | Somewhat important | Least important |

| Social (Group) Equality | Somewhat important | Least important | Most important |

| Role of Government | Wealth distributor | Referee of fair competition | Protector of the equal collective treatment |

| Socio-Eonomic Preference | Order and stability | Freedom to pursue new opportunities | Equality among groups |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ottesen, A.; Thom, D.; Bhagat, R.; Mourdaa, R. Learning from the Future of Kuwait: Scenarios as a Learning Tool to Build Consensus for Actions Needed to Realize Vision 2035. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7054. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097054

Ottesen A, Thom D, Bhagat R, Mourdaa R. Learning from the Future of Kuwait: Scenarios as a Learning Tool to Build Consensus for Actions Needed to Realize Vision 2035. Sustainability. 2023; 15(9):7054. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097054

Chicago/Turabian StyleOttesen, Andri, Dieter Thom, Rupali Bhagat, and Rola Mourdaa. 2023. "Learning from the Future of Kuwait: Scenarios as a Learning Tool to Build Consensus for Actions Needed to Realize Vision 2035" Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7054. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097054

APA StyleOttesen, A., Thom, D., Bhagat, R., & Mourdaa, R. (2023). Learning from the Future of Kuwait: Scenarios as a Learning Tool to Build Consensus for Actions Needed to Realize Vision 2035. Sustainability, 15(9), 7054. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097054