Abstract

Peer interaction through play is one approach to stimulating preschool children’s growth. The outdoor playground facilities in parks are ideal places for children to practice their social skills. This study utilized nonparticipant observation to observe and record children’s play behaviors and interactions with others to ascertain whether outdoor playground facilities favor peer interaction. We summarized the design elements of peer-interaction-promoting playground facilities to optimize the facilities by determining the types of environments and facilities that trigger peer interaction. This study discovered that children spent most of their time in solo play and the least in peer interaction. Such interaction occurred only in spaces in which children stopped briefly. After installing a new bubble machine designed to increase peer interaction, solo play behaviors and parent–child interactions became less frequent for children younger than six years old, whereas peer interaction became more frequent. During the peer interaction of children aged 3 to 6, the frequency of level one, three, and four interactions increased. They also displayed level five behaviors, which were not observed before the installation. The new facility triggered higher-level behaviors, such as cooperation and playing together, enhancing peer interaction between different age groups.

1. Introduction

Play is a freely chosen intrinsically motivating behavior that actively attracts children [1]. Joy is inherent and required for an activity to be considered play. Even in the most constrained definitions of play cited above, joy is a central characteristic, despite the well-documented evidence that play sparks learning opportunities [2,3,4]. Play is notoriously tricky to define [5,6,7]. Ashby et al. [8] proposed a neuropsychological theory relating positive effects to long-term and working memory and creativity in problem-solving. Indeed, positive affect is linked to increased creativity [9], and creative thinking is related to improved learning [3,10]. Arguably play often includes joy, agency, flexibility, active engagement, social interaction, an iterative nature, imagination, and structure of some sort [2,3,5,6,7]. Play can support social, emotional, cognitive, and physical development [11,12,13,14,15]. Zosh et al. [3] recently presented five characteristics of play. For an activity to be considered playful, it should include elements of (1) joy, (2) active engagement, (3) meaning or relevance, (4) social interaction, and (5) iteration and variety. Not all characteristics need to be present for an activity to be considered playful; however, play will have the most significant benefits for child development when integrated into an activity.

Play includes freedom of choice, personal guidance, and intrinsic motivational behavior. It is not performed to reach external goals or obtain rewards but is an essential and indispensable part of healthy development for children and the society in which they live [16]. Children define goals and interests in play, defining success and failure and pursuing their goals in their manner [17]. The relationship between play modes and child development is complex [18]. Charlesworth [19] believed that play could help children improve their communication, self-control, social skills, language, reading and writing, and problem-solving skills, while increasing their curiosity, playfulness, and social cognitive ability.

Moreover, play can develop the ability to differentiate between fantasy and reality and provide tools for adults to learn how children see the world. Hartup [20] reported that peers are crucial intermediaries in children’s socialization, influencing their gender-role learning, moral development, and control of aggressive behavior. Peers acquire social skills and establish interpersonal relationships through interaction. The development of peer relationships is closely related to children’s social abilities. These abilities develop their cognition and help children become more able to express and control emotions. Social play refers to social interaction through games, which require children to get along with others. This includes an ability to interact with others daily, such as through sharing, taking turns, and allowing others to express their opinions; self-control skills, such as appropriate control and expression of anger, are also part of social play.

Although Park and Lee [21] suggest that one of the advantages of working with a peer is benefiting from a higher-ability peer or one with higher social skills, even the illusion of working collaboratively has positive effects. Cognitive and social-emotional development are interrelated: social competence has been highlighted as a prerequisite for academic success and mental growth [11,12,14,15,22,23,24].

Children’s perception of play is shaped by their experiences [25]. Social play encourages children to focus on the rules of play, enabling them to understand all social interactions under a particular direction. Hart [26] stressed the importance of public playgrounds to civil society and democracy because they allow children to interact with people of different ages, growth backgrounds, and social classes, shaping cultures and communities. When children engage in free play with peers, they practice social interaction, expressive communication, and behavioral regulation [27]. Research examining 6- and 7-year-olds’ unstructured time revealed that the more time children spent in unstructured activities, the better their self-directed executive function skills [28]. Therefore, peer play has a strong effect on the development of children’s social behavior. In particular, the social development of children aged 3–6 years is primarily based on peer interaction. After observing peer play, Howes and Matheson [29] developed the peer play scale based on the complexity of mutual interactions (Table 1). The instrument enables thorough observation of children’s social play.

Table 1.

The Peer Play Scale (The scale is based on Howes and Matheson [29], organized in to a table by the author of this paper).

An outdoor playground is where users of all ages and different growth backgrounds can play. Senda [30] noted that a children’s play environment contains four elements—place, time, playmates, and activities. A rich play environment should provide its participants with sufficient time and space. Play equipment is essential for play, enticing children to enter and play unconsciously and freely. Several countries [16,17] have developed policies emphasizing children’s play’s importance. Senda [30] identifies a common sequence of behaviors in children’s use of play structures. At the first stage of functional play, children use the equipment as intended, for example, climbing up the steps and sitting to go down the slide. After some experience, children move on to a stage of technical play. Now enjoyment comes from exploring new ways of using the structure. Children begin using playground facilities to engage in play activities, such as hide, seek, and tag. Play facility provides an impetus to move on to another stage, social play.

Playgrounds, the most common feature of neighborhood parks, are prime attractions that draw families with young children to parks [31]. Children need a place to find and create play to enhance their capabilities and expand their social world through exploration, play, and experience of the physical world [26]. An outdoor play area is excellent for children to interact with peers. Weinstein and Pinciotti [32] noted that an increase in spatial fluidity is related to an increase in children’s functional play and a decline in social interaction. Hou and Chen [33] stated that the characteristics of a playground environment—such as crowds, event integration, space invitation, and open communication—are crucial social attraction factors that influence children’s judgment of the playground.

Some research suggests that 2- to 5-year-old children’s participation in structured and enriched activities does not necessarily predict their cognitive, social, and physical outcomes [34]. Children thrive when offered some balance between the freedom of unstructured time to explore and self-direct their learning and more pointed and directed activities.

While free play has traditionally been recognized as optimal for promoting social interaction, even in play with peers, adults need to scaffold and protect the playful peer interaction [35] as even young children are susceptible to social loafing [36], bullying [37], and exclusion [38], suggesting that guided play may have a role in the development of positive social skills. Play that requires or encourages negotiating rules and limitations, taking the perspective of other players, and collaboratively creating play worlds or frameworks with peers has been linked to greater recognition that other people have unique perspectives and mindsets [27,39].

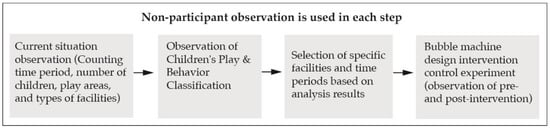

Although childhood offers important opportunities to establish active play habits, we do not understand developing and sustaining active play among children [40]. This is an exploratory study, and the authors observed and experimented with children’s play behaviors at the combined playground facilities in the children’s play area of Daan Forest Park. The interaction subjects and play behaviors of children aged 3–6 years during peer interaction were understood through observation. How play equipment can be designed to increase peer interactions was determined based on the observation results. In addition, the effects of pre-established versus new playground facilities on peer interaction were evaluated. Figure 1 shows the research steps of this study. In this study, we used non-participant observation, a well-validated method [41,42,43,44], because we wanted to observe children’s most natural behaviors.

Figure 1.

Research step-by-step diagram.

2. Current Situation Observation and Analysis

2.1. Location

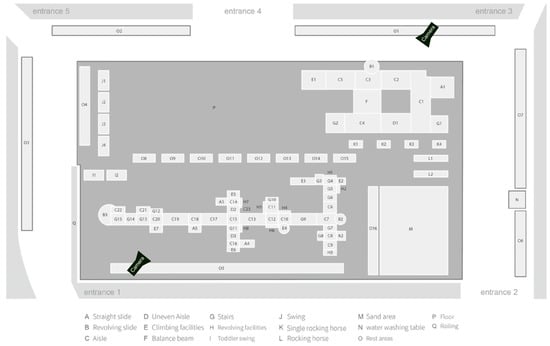

The present study investigated the children’s play area in Daan Forest Park (Figure 2), located in the Taipei metropolitan area. The park is adjacent to the main roads of Taipei City, resulting in convenient transportation. Daan Forest Park is the largest urban park in Taipei, covering an area of 26.114 hectares. This study focused on the children’s play area on the northeast side of the park, consisting of two sets of large-scale combined playground facilities (Figure 3). Different independent playground facilities are used within the area and cater to children of different ages. We set up multiple cameras, and all the personal data in the observation records are de-identified and processed. Although we do not have a demographic profile of our park users, we believe we can effectively present the user’s behavior patterns by observing and faithfully recording the children’s play activities using the area without hindrance.

Figure 2.

Children’s play area in Daan Forest Park.

Figure 3.

Classification codes of the play area in Daan Forest Park and camera locations.

2.2. Objects

Because it was impossible to observe the multiple entrances to the play area simultaneously during recording, we observed the number of people entering the playground from each entrance from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. on different days. The target groups we selected were composed of at least one adult and one child. A total of 649 target groups were observed. We found the number of people entering from the five entrances was in the ratio 4:2:4:2:1 based on previous observation records, which served as the basis for sample selection in Observation 1. After observing the target groups entering from the five entrances in sequence based on the ratio mentioned earlier, we proceeded to the next round of observation using the same ratio.

Non-participant observation was employed during the observation. Video recording commenced when a target group entered the play area and ceased when they left. A single caregiver–child group was recorded each time, and the behavior of 39 target groups (a caregiver with a child, a total of 78 individuals) in the play area was recorded. Multiple cameras could record the movements of the target group without them knowing it was being filmed. We looked at the behavior, and we did not include sound. Each group began when the target group entered the field and ended when they left the area. The observation was conducted between 2 and 4 p.m. on weekdays, when many people were in the play area. Since it was a non-participant observation, we conducted no interviews with the subjects. Therefore, we estimated the children’s heights based on their height compared to the playground entrance railings and used heights to correspond to probable ages. The reference for this information comes from the Taiwan Children’s Growth Curve provided by the Health Promotion Agency of the Ministry of Health [45]. The height of children aged 3–6 is 96–110 cm.

2.3. Data Collection and Coding

The videos were recorded in coded form. The behaviors of the children using a single playground facility were divided into solo play, caregiver–child interaction, and peer interaction. The time of appearance of a behavior was recorded using a code, and the percentage of time spent in one behavior was determined by dividing the duration spent in that behavior by the total time the child spent in one area.

((The duration the child or caregiver spent in that behavior/the total time the child or caregiver spent in one area) × 100% = percent of time spent in one behavior).

Caregiver–child interaction was considered to include waiting, eye contact, and searching, whereas peer interaction included speaking and physical contact. Children’s play was understood using the peer play scale of Howes [29] (Table 2). There are two coders for coding processing after observation. Cohen’s kappa coefficient [46,47] is used to confirm that the coding consistency of the two coders must be greater than 0.6 before being included in the analysis data.

Table 2.

Behavior codes of observation.

2.4. Observation Results

During the first observation stage, each child spent an average of 17 min in the playground. Christie, Johnsen, and Perckover [48] noted that higher-level peer interaction was more likely when a child’s playing time was more than 30 min, indicating that most children were not present long enough for peer interaction. The floor was the most used area because it was used to change between activities; slides were the second most commonly used facility. Solo play facilities was the most common type (48%), followed by caregiver–child interaction facilities (37%). The least time was spent using peer interaction facilities (15%).

Caregivers looked after their children in various ways: following and watching, standing and watching, sitting and watching, standing and waiting, and sitting and waiting. Standing and watching was the most common caregiver behavior (25.13%), followed by following and watching (23.75%). The caregivers spent the last time sitting and watching (3.71%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Caregivers’ care behavior in the play area.

Peer Interaction Behavior Displayed by Children Aged 3–6 Years during Play

Peer behavior was most frequent on the floor (P), revolving facilities (H3), the rocking horse (L1), straight slide (A), and large spaces (G1). Peer interaction was most frequent in playground facilities with ample surrounding space where children could linger. By contrast, peer behavior was rarely observed in aisles (C) or rest areas (O) that connected different playground facilities. Level one behavior (simple parallel play) in the peer play scale was the most frequently observed behavior (28.75%), indicating that children often used the facilities alone during play. The percentage of levels two (parallel play with mutual regard, 10.79%) and four (complementary play with mutual awareness, 7.54%) behavior was not too far behind, whereas the percentage of level three behavior (2%) was the lowest. Therefore, when children were playing in the outdoor playground, they spent little time in verbal and physical contact (level three) before progressing to level four (Table 4).

Table 4.

Places where behavior is prone.

Level 1 (simple parallel play): Level one involved children performing similar activities within 3 feet of each other but unaware of the other’s presence.

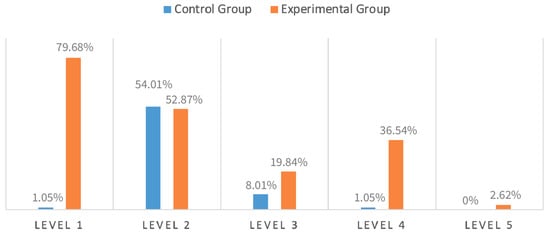

Level 2 (parallel play with mutual regard): Children spent the most time looking at others (9.07%), such as at the swings (J4) and rocking horses (L1 and K3), and areas with no facilities such as the rest areas outside the playground (O4 and O7) and railing (Q). These areas provide time for lingering; children could observe what others were doing and imitate them when using the area.

Level 3 (simple social play): Level three behaviors were most common in spaces with shelters, indicating that shelters created a sense of enclosure conducive to simple social play behaviors. In the main entrances to the play areas, children were prone to behaviors such as physical contact or talking when using them.

Level 4 (complementary play with mutual awareness): Waiting, finding, and initiative following, passive following, and playing together were observed in level four peer interaction; playing together accounted for the highest total play time (5.33%). The major locations where level four behaviors occurred were the aisles, entrances, and exits. However, children were not found to play together in E5 and E6 because the areas in each unit were relatively narrow, which was unconducive to quick movement during play. This revealed that playground facilities should have sufficient space for children to maintain quick movement without interruption.

In general, peer interaction was more commonly observed in spaces where children could temporarily remain for a short time, stopping their play. These spaces allowed children to observe others’ behaviors, which could lead to higher-level peer interaction. The lowest-level simple parallel behaviors were the most frequent, indicating that children often employed the playground facilities. Level three behaviors, such as speaking and physical contact, accounted for only a small percentage of the total playtime despite being necessary to progress to level four behaviors.

3. Methods

3.1. Stimuli

Based on the findings obtained in the first stage, a new bubble machine was established in the field where children stay less to verify whether it improved peer interaction. We recorded children’s behavior for two days in one week through non-participant observation to avoid climate effects. We used non-participant observation for two days and selected the target group the same way as before, based on the number of people entering each entrance. One of the two days was for the control group to recheck usual usage conditions. A new bubble machine was established on another day as the experimental group.

3.2. Choice of Facilities

In the design, the priority was to create a difficult operation method, to cause children to spend some time familiarizing themselves with the facility, thereby creating opportunities for peer interaction. Operation methods and sudden events could trigger children’s attention and the imitation of others. A see-through design through which children could observe each other was selected for the wall to promote children’s level two behavior (parallel play with mutual regard). An enclosed space can cause children to produce multilevel play behaviors and encourage them to stay still for a short period, potentially triggering social play behaviors at level three or higher. Therefore, a space with a sense of enclosure was designed. The facility was created with entrances, exits, and easy access so children could choose whether to join or leave the play area. The designed play area featured H3 (revolving facilities) and enclosed spaces that provided places to stay for a short period. In the preceding observations, C9 (aisle of the slider set) was observed to be the location of the least peer interaction (0%) during children’s play. Since we found in our initial observation that some children will play near the play facility with portable bubble toys, it was clear that the behavior of blowing bubbles attracts the attention of children. Therefore, we decided to use a bubble machine as a design intervention. In the designed facility, a bubble machine with a red button was installed at C9, and activities at the location were recorded using a camera from a distance (Figure 4). The height of the partition boards in the facility was 95 cm, the minimum standard for the average height of children aged 3–7 years. This height was used as the basis for judging the age of children during observation; height surpassing one-third of the red partition board at its upper edge was used to indicate the observed children’s height range.

Figure 4.

Installation and location of new facility design.

We selected the experimental and control groups for observation from 3:30 p.m. to 6:30 p.m. on different weekdays. This is the time period when the most people use the play equipment during summer weekdays. After observation, the time of each behavior was recorded with a behavior code.

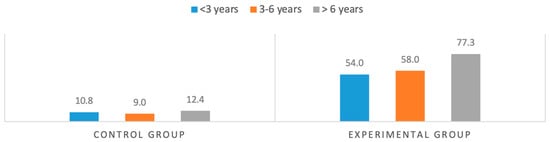

4. Results

Based on their height, the observed children were divided into Groups A (<3 years), B (3–6 years), and C (>six years). The number of observed children in the experimental and control groups in the same timeframe was 264 and 56 (Table 5), respectively. The number of users after installation of the bubble machine was approximately five times that before this installation. The average use time per child before bubble machine installation was 10 s, which increased to 63 s after installation, indicating that the bubble machine activated the area. Considerable improvement was discovered in the use time of all three age groups (Figure 5).

Table 5.

Number of children in each group.

Figure 5.

The average use time of each group using the facility.

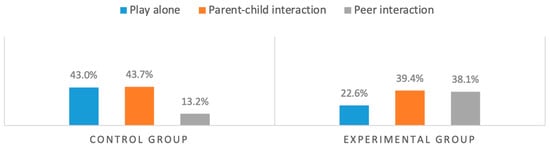

- Interaction among Group A children

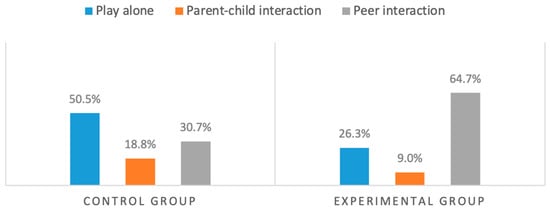

Group A consisted of children younger than three years old; these children demonstrated the most frequent interaction with their caregivers and tended to play alone, thus exhibiting the least frequent peer interaction. However, peer interaction was higher after bubble machine installation, halving the percentage frequency of solo play. Therefore, installing the bubble machine caused children younger than three years to spend more time with their peers using the facility, increasing the opportunity for peer interaction (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Percentage of interaction among Group A children (<3 years) using the facility.

- 2.

- Interaction among Group B children

The children in this group were aged 3–6 years. Before installing the bubble machine, Group B children tended to play alone, with peer interaction the second most common type of play; caregiver–child interaction was relatively infrequent. After the installation of the bubble machine, peer interaction became more frequent. In contrast, the percentages of time spent in solo play and caregiver–child interaction decreased, indicating that the bubble machine helped peer interaction among children aged 3–6 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Percentage of interaction among Group B children (3–6 years) using the facility.

- 3.

- Interaction among Group C children

Group C children consisted of school-age children older than six who focused on group play in social development, with their caregivers gradually being replaced in status by their peers [49]; thus, caregiver–child interaction was infrequent during the two observations. When using the designed facility, Group C children exhibited less frequent peer interaction and spent more time in solo play. They tended to use the facility alone and even prevent other children from using it (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Percentage of interaction among Group C children (>six years) using the facility.

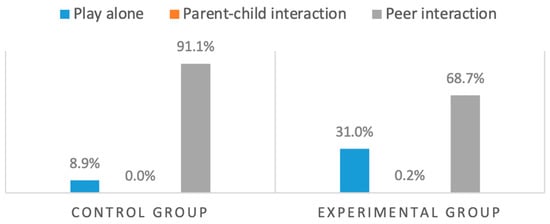

Among children aged 3–6 years (Group B), the experimental group displayed more peer interaction except for level two behaviors (parallel play with mutual regard). The number of users was higher following the installation of the new facility in the playground, with many children often gathering at the location; thus, increased level one behavior (simple parallel play) was observed. Level two behaviors (parallel play with mutual regard) consisted of simple parallel play with eye contact and imitation of others. Despite level two behaviors being slightly less common following the installation of the bubble machine, children spent more time in higher-level interactions such as speaking, physical contact, and playing together. Furthermore, level five behaviors (complementary social play) that did not occur in the previous observations also appeared (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Percentages of interactions at all levels when Group B children (aged 3–6 years) were using the new facility.

- Level 1: simple parallel play

Level 1 behavior (simple parallel play) refers to children performing similar activities within 3 feet of each other without being aware of others’ presence. After installing the bubble machine, the number of users in the area increased, and numerous children often gathered there. Children were often too focused on operating the facilities. They did not realize that more and more children were gathering around them, leading to a drastic increase in the appropriate behavior. The percentage of level one behavior among the experimental group was 79.68%, higher than that for the control group (1.05%).

- Level 2: parallel play with mutual regard

Before the bubble machine installation, children looked at other children below from the area’s window (C9). However, after the bubble machine installation, children often watched those operating the facility from the entrance to the field, an action that may have attracted children to stop and watch. Alternatively, they may have observed the reaction of the children below from the railing, indicating that the transparency of the walls in the facility was crucial to peer interaction (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Percentage of level 2 interactions (parallel play with mutual regard) for Group B children (3–6 years) using the facility.

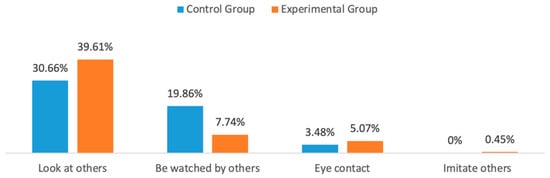

- Level 3: simple social play

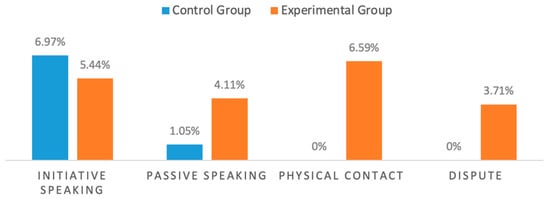

Level three behaviors (simple social play) refer to behaviors such as speech, provision and acceptance of playthings, physical contact, and conflict but not assistance among children. At this level, three interactions were observed in the control data. After the bubble machine installation, children’s initiative speaking was less common, whereas passive speaking was more common. This was because other children often spoke to the children operating the facility, with the content of this speech being propositions that others are allowed to use the facility. Moreover, some children actively notified other children that the bubbling water had been exhausted. Physical contact and disputes were more common in the experimental data. Physical contact primarily comprised pushing and disputes among children who wanted to operate the facility. In addition, older children were observed to stop or discourage other children from arguing, indicating that the facility increased communication between children of different ages despite causing conflict (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Percentage of level 3 interactions (simple social play) for Group B children (3–6 years) using the facility.

- Level 4: complementary play with mutual awareness

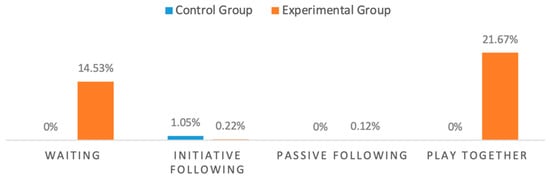

Level four interactions (complementary play with mutual awareness) were more frequent in the experimental data, primarily focused on waiting and playing together. Children queued and waited for their turn to operate the facility, inducing level two (parallel play with mutual regard) and level three (simple social play) interactions such as gazing, speaking, and physical contact. Playing-together behavior was children’s primary interaction at different positions in the experimental data. One child used the facility while other children below or beside them played with the bubbles without gazing at or talking to each other. Up to six children below were attracted, and up to seven children played together while using the facility, indicating that multiple children could use the facility together. However, it had only one operating mechanism (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Percentage of level 4 interactions (complementary play with mutual awareness) for Group B children (3–6 years) using the facility.

- Level 5: complementary social play

Playing together behavior under level five interaction (complementary social play) did not appear in control data; however, it was observed in the experimental data (2.62%), indicating that the facility promoted higher-level interactions. The behaviors included the children operating the facility watching the reaction of the children below and the children below looking up because the bubbles attracted them. Both parties thus produced behaviors such as eye contact and conversation and played together (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

The new facility was attractive, whereas peer interaction became more frequent.

5. Discussion

5.1. Transformation by Design Intervention

The observation was divided into experimental and control groups, and the cameras were set up for three hours on two weekdays in the afternoon. Children mostly passed by C9 and rarely entered the area before the bubble machine was installed. After its installation, the number of children using the area increased approximately fivefold, with the use time of a single child increasing sixfold, indicating that the new facility was attractive to them. Children younger than six years exhibited less solo play and caregiver–child interaction, whereas peer interaction became more frequent, indicating that the design helped preschool children develop peer interaction. Interaction and communication among peers help children grow and develop [33,34]. Because of the school-age children occupying the facility, the frequency of solo play behavior and peer interaction increased and declined, respectively. Among the types of peer interaction, those of levels one, three, four, and five became more frequent. Children exhibited lower-level behaviors such as speaking and physical contact while waiting, and disputes gave children the opportunity to communicate with children of different ages. Children displayed higher-level behaviors such as cooperation and playing together. Although gamification can negate real life [50], on the other hand, it is also a socialization and protection mechanism. In terms of communication, it develops self-virtualization and trains communication skills. In the social environment of the playground, the ability to play with the permission of adults and other children through interaction and communication is the primary and core experience of outdoor play, which is fun [51,52,53,54,55,56].

5.2. Caregiver–Child Interaction

The value of play in the practice and development of self-regulation has long been recognized [57]. We found that approximately one-third of the caregivers accompanying their children were grand caregivers; intergenerational interaction has thus become a major type of caregiver–child interaction. Children spent most of their time playing alone, interacting with their caregivers or grand caregivers. Peer interaction was the least common and frequent behavior. Independent facilities and those that were difficult to operate led to caregivers and children using them together, and caregiver assistant behavior was observed frequently. Caregivers tended to search for their children when they were in a high location or narrow and enclosed space with walls obscuring the caregivers’ line of sight. Children would ask their caregivers for help by looking at them when they encountered difficulty using the facilities. Accordingly, spatial environments and unobstructed sight are crucial in designing a play area. Although both Smith [58] and Thomson [59] mentioned that adults often have to play the role of supervisor, this role may hinder children’s choices in play. Observations in the present study revealed more peer interaction at locations where children briefly stayed still and paused their play. Children were capable of higher-level play behavior after engaging in only short conversations. They tended to look at others when operating independent facilities, at locations with walls that offered a clear view, and in locations that enabled a brief rest. Particular spatial characteristics such as narrow and oppressive areas (entrances and exits of facilities) often triggered level three interactions. Level four behaviors (complementary play with mutual awareness) were common at the connection ports of facilities or in broad areas with smooth traffic flow. The number of people using the facilities increased after a bubble machine was installed, indicating that the design was attractive to children. After the installation, children younger than six years displayed less frequent solo play and caregiver–child interaction.

5.3. Peer Interaction

In contrast, peer interaction was more frequent, indicating that the design facilitated peer interaction among preschool children. In the initial observations, peer interaction was the least observed behavior category. In the present study, we found an increase in Level one, three, and four interactions in the target group (children aged 3–6 years) after installation against the Peer Play Scale [29] categorization. Furthermore, level five interaction (complementary social play), which did not appear during the control observation, was observed, indicating that the new facility led to higher-level behaviors such as cooperation and playing together. The facility could accommodate multiple children and improve peer interaction between all age groups.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Contribution

In this study, we focus on how children interact with each other in public playgrounds and how to promote higher levels of interaction. Facilities should be designed that require children to familiarize themselves with their operation method; this produces the opportunity for peer interaction. Single-play methods and sudden events may trigger children to exhibit behaviors such as gazing at and imitating others. The partition of facilities should be installed in spaces that provide an open view to promote level two play behavior (parallel play with mutual regard). Enclosed spaces can trigger multilevel play behaviors and temporarily cause children to stay in a location. Increasing a child’s stationary time leads to greater opportunity for level three (or higher) social play behavior. Therefore, enclosed spaces can be established in facilities that are easy to enter or exit or at the entrances and exits of play areas, despite scholars’ claims that outdoor games are no longer favored by children [35,60]. This study validated that installing a simple bubble machine can promote peer interaction while revitalizing a legacy facility. Each play equipment has its own applicable children’s age, play method, and purpose. We suggest that this flexible design can be added to less popular play equipment or areas so that each piece of play equipment can be more evenly distributed, increasing the playability of the facilities or triggering new ways to play for children. Our research contribution mainly provides a research methodology and design interventions to allow existing play facilities to function in the spirit of sustainable development.

6.2. Future Research and Development

In this study, we installed a bubble machine in an obscure Daan Forest Park area, which successfully caused peer interaction. However, it is unclear whether these will affect each other in quantity. The follow-up maintenance cost of installing a bubble machine also needs careful evaluation. This study was conducted under favorable weather conditions, so the influence of environmental factors such as climate at different periods needs to be recorded for a long time. Follow-up research can continue to focus on user behavior and understand new issues in downstream devices for long periods of use. This study provides behavioral notation in the form of non-participant observation and incorporates design interventions to observe behavioral change. We encourage similar approaches to be taken in other community playgrounds of different types and consider the benefits of design-validated facilities to promote more interaction with children in play.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, J.-T.Y.; writing—review and editing, visualization, C.-I.C.; resources, supervision, project administration, M.-C.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Due to confidentiality agreements, supporting data can only be made available to bona fide researchers subject to a non-disclosure agreement. Details of the data and how to request access are available from Meng-Cong Zheng (zmcdesign@gmail.com) at the National Taipei University of Technology.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to all participants who generously shared their time and experience for the purposes of this study section.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- National Children’s Office. Ready, Steady, Play: A National Play Policy. 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/183b50-ready-steady-play-a-national-play-policy/ (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Yogman, M.; Garner, A.; Hutchinson, J.; Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Golinkoff, R.M.; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Council on Communications and Media; Baum, R.; Gambon, T.; Lavin, A.; et al. The power of play: A pediatric role in enhancing development in young children. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20182058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zosh, J.M.; Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Hopkins, E.J.; Jensen, H.; Liu, C.; Neale, D.; Solis, S.L.; Whitebread, D. Accessing the inaccessible: Redefining play as a spectrum. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillard, A.S.; Lerner, M.D.; Hopkins, E.J.; Dore, R.A.; Smith, E.D.; Palmquist, C.M. The impact of pretend play on children’s development: A review of the evidence. Psychol. Bull 2013, 139, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, P. What exactly is play, and why is it such a powerful vehicle for learning? Top Lang. Disord. 2017, 37, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassinger-Das, B.; Toub, T.S.; Zosh, J.M.; Michnick, J.; Golinkoff, R.; Hirsh-Pasek, K. More than just fun: A place for games in playful learning/Más que diversión: El lugar de los juegos reglados en el aprendizaje lúdico. Infanc. Aprendiz. 2017, 40, 191–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisberg, D.; Zosh, J.M.; Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Golinkoff, R. Talking It Up: Play, Language Development, and the Role of Adult Support. Am. J. Play 2013, 6, 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby, F.G.; Isen, A.M.; Turken, A.U. A neuropsychological theory of positive affect and its influence on cognition. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 106, 529–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isen, A.M.; Daubman, K.A.; Nowicki, G.P. Positive Affect Facilitates Creative Problem Solving. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, M. All i really need to know (about creative thinking) i learned (by studying how children learn) in kindergarten. In Proceedings of the Creativity and Cognition 2007, CC2007—Seeding Creativity: Tools, Media, and Environments, Washington, DC, USA, 13–15 June 2007; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, S.H.; Ladd, G.W. The teacher-child relationship and children’s early school adjustment. J. Sch. Psychol. 1997, 35, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, B.K.; Pianta, R.C. Early Teacher–Child Relationships and the Trajectory of Children’s School Outcomes through Eighth Grade. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Golinkoff, R.M.; Berk, L.E.; Singer, D.G. A Mandate for Playful Learning in Preschool: Presenting the Evidence; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-14352-000 (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Konold, T.R.; Pianta, R.C. Empirically-Derived, Person-Oriented Patterns of School Readiness in Typically-Developing Children: Description and Prediction to First-Grade Achievement. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2010, 9, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, G.W.; Herald, S.L.; Kochel, K.P. School Readiness: Are There Social Prerequisites? Early Educ. Dev. 2010, 17, 115–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh Assembly Government. A Play Policy for Wales; National Assembly for Wales: Bridgend, UK, 2002.

- Draft Play Policy for Northern Ireland. In Children and Young People’s Unit|The Royal Marsden; Office of the First and Deputy First Minister: Belfast, UK, 2008. Available online: https://www.royalmarsden.nhs.uk/our-consultants-units-and-wards/clinical-units/children-and-young-peoples-unit (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- McHale, S.M.; Crouter, A.C.; Tucker, C.J. Free-Time Activities in Middle Childhood: Links with Adjustment in Early Adolescence on JSTOR. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 1764–1778. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3654377 (accessed on 16 March 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlesworth, R. Understanding Child Development: For Adults Who Work with Young Children; Delmar Publishers: Albany, NY, USA, 1992; Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Understanding_Child_Development.html?hl=zh-TW&id=VoQrAQAAMAAJ (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Hartup, W.W. The social worlds of childhood. Am. Psychol. 1979, 34, 944–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, J. Dyadic Collaboration Among Preschool-Age Children and the Benefits of Working With a More Socially Advanced Peer. Early Educ. Dev. 2015, 26, 574–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, L.E.; Mann, T.D.; Ogan, A.T. Make-Believe Play: Wellspring for Development of Self-Regulation. In Play = Learning: How Play Motivates and Enhances Children’s Cognitive and Social-Emotional Growth; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Why improving and assessing executive functions early in life is critical. In Executive Function in Preschool-Age Children: Integrating Measurement, Neurodevelopment, and Translational Research; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 11–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golinkoff, R.M.; Hirsh-Pasek, K. Becoming Brilliant: What Science Tells Us about Raising Successful Children; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Westcott, M.; Howard, J. Creating a playful environment; evaluating young children’s perceptions of their daily classroom activities using the Activity Apperception Story Procedure. Psychol. Educ. Rev. 2007, 31, 27. Available online: https://scholar.google.com.tw/scholar?hl=zh-TW&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Creating+a+playful+environment%3B+Evaluating+young+children%E2%80%99s+perceptions+of+their+daily+classroom+activities+using+the+Activity+Apperception+Story+Procedure.&btnG=#d=gs_cit&t=1678969224630&u=%2Fscholar%3Fq%3Dinfo%3AQR33SDhScUQJ%3Ascholar.google.com%2F%26output%3Dcite%26scirp%3D0%26hl%3Dzh-TW (accessed on 16 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Hart, R. Containing Children Some Lessons on Planning for Play from New York City. Provis. Play 2002, 14, 135–148. Available online: https://www.studypool.com/documents/1659981/containing-children-some-lessons-on-planning-for-play-article- (accessed on 16 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Blatchford, P.; Baines, E. Peer Relations in School. In International Handbook of Psychology in Education; Littleton, K., Wood, C., Staarman, J.K., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, J.E.; Semenov, A.D.; Michaelson, L.; Provan, L.S.; Snyder, H.R.; Munakata, Y. Less-structured time in children’s daily lives predicts self-directed executive functioning. Front Psychol. 2014, 5, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, C.; Matheson, C.C. Sequences in the Development of Competent Play With Peers: Social and Social Pretend Play. Dev Psychol. 1992, 28, 961–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senda, M. Design of Children’s Play Environments; McGraw-Hill Companies: New York, NY, USA, 1992; p. 186. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.A.; Han, B.; Nagel, C.J.; Harnik, P.; McKenzie, T.L.; Evenson, K.R.; Marsh, T.; Williamson, S.; Vaughan, C.; Katta, S. The First National Study of Neighborhood Parks: Implications for Physical Activity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, C.S.; Pinciotti, P. Changing a schoolyard: Intentions, Design Decisions, and Behavioral Outcomes. Environ. Behav. 1988, 20, 345–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Chen, Z. Children’s Environmental Cognition to Children’s Playgrounds. Outdoor Recreat. Res. 1998, 11, 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffrin, H.H.; Godfrey, H.; Liss, M.; Erchull, M.J. Intensive Parenting: Does it Have the Desired Impact on Child Outcomes. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 2322–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri, F.; Wien, C.A. ‘Give Us a Privacy’: Play and Social Literacy in Young Children. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2005, 19, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arterberry, M.E.; Cain, K.M.; Chopko, S.A. Collaborative Problem Solving in Five-Year-Old Children: Evidence of social facilitation and social loafing. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirves, L.; Sajaniemi, N. Bullying in early educational settings. Early Child Dev. Care 2012, 182, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanger, S.M.; Frankel, L.A.; Hazen, N. Peer Exclusion in Preschool Children’s Play: Naturalistic Observations in a Playground Setting. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2012, 58, 224–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, G.M. Play as Regulation. Top Lang. Disord. 2017, 37, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, B.; Telford, A.; Finch, F.C.; Benson, C.A. Moving Physical Activity Beyond the School Classroom: A Social-ecological Insight for Teachers of the facilitators and barriers to students’ non-curricular physical activity. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 37, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.A.; Talarowski, M.; Han, B.; Williamson, S.; Galfond, E.; Young, D.R.; Eng, S.; McKenzie, T.L. Playground Design: Contribution to Duration of Stay and Implications for Physical Activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.A.; Setodji, C.; Evenson, K.R.; Ward, P.; Lapham, S.; Hillier, A.; McKenzie, T.L. How Much Observation Is Enough? Refining the Administration of SOPARC. J. Phys. Act. Health 2011, 8, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, M.F.; Bocarro, J.N.; Smith, W.R.; Baran, P.K.; Moore, R.C.; Cosco, N.G.; Edwards, M.B.; Suau, L.J.; Fang, K. Park-based physical activity among children and adolescents. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, J.W.; Larson, L.R.; Green, G.T. Monitoring visitation in Georgia state parks using the System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities (SOPARC). J. Park Recreat. Admi. 2012, 30, 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Health Promotion Administration-MOHW. Growth Curve of Children Aged 0–7. January 2015. Available online: https://www.hpa.gov.tw/Pages/Detail.aspx?nodeid=870&pid=4869 (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, N.J.-M.; Koval, J.J. Interval estimation for Cohen’s kappa as a measure of agreement. Statist. Med. 2000, 19, 723–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, J.F.; Johnsen, E.P.; Peckover, R.B. The Effects of Play Period Duration on Children’s Play Patterns Patterns. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2009, 3, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X. Play and Child Development; Yangzhi Culture: Taipei, Taiwan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kačerauskas, T.; Sedereviciute-Paciauskiene, Z.; Sliogeriene, J. Gamification in socio-cultural structures: Advantages and disadvantages. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2022, 21, 181–192. Available online: https://web.s.ebscohost.com/abstract?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=16484460&AN=157061087&h=RZd3D2o3qEnR3SLeWhnZID4qVGVMweECEBPx7V03FI%2fKmq2RMiY1ktfP2BZwJo7D9fTzjer1QYvEYjrAvTthvg%3d%3d&crl=c&resultNs=AdminWebAuth&resultLocal=ErrCrlNotAuth&crlhashurl=login.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26profile%3dehost%26scope%3dsite%26authtype%3dcrawler%26jrnl%3d16484460%26AN%3d157061087 (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Caro, H.E.E.; Altenburg, T.M.; Dedding, C.; Chinapaw, M.J.M. Dutch Primary Schoolchildren’s Perspectives of Activity-Friendly School Playgrounds: A Participatory Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminpour, F. The physical characteristics of children’s preferred natural settings in Australian primary school grounds. Urban For. Urban Green 2021, 62, 127163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitsikali, A.; Parnell, R. The public playground paradox: ‘child’s joy’ or heterotopia of fear. Child Geogr. 2019, 17, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahy, S.; Delicâte, N.; Lynch, H. Now, being, occupational: Outdoor play and children with autism. J. Occup. Sci. 2021, 28, 114–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, J.; Kraftl, P. Three playgrounds: Researching the multiple geographies of children’s outdoor play. Environ. Plan. A: Econ. Space 2018, 50, 214–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenthaler, T.; Schulze, C.; Pentland, D.; Lynch, H. Environmental Qualities That Enhance Outdoor Play in Community Playgrounds from the Perspective of Children with and without Disabilities: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitebread, D.; O’Sullivan, L. Preschool children’s social pretend play: Supporting the development of metacommunication, metacognition and self-regulation. Int. J. Play 2012, 1, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumerling, B. A place to play: An exploration of people’s connection to local greenspace in East Leeds. In Conscious Cities; Academia: Prague, Czech Republic, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, S. A well-equipped hamster cage: The rationalisation of primary school playtime. Education 3–13 2003, 31, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, S.-A. Children in the Outdoors; Sustainable Development Research Centre: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).