Validation of an Instrument on Perceptions of Heritage Education through Structural Equation Modeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objective

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Research Design

2.4. Participants

2.5. Procedure and Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Troyer, V. HEREDUC–Patrimonio Culturale in Classe: Manuale Pratico per gli Insegnanti; Garant Uitgevers: Antwerpen, Belgium, 2005; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli, M. Heritage Interpretation. Un Nuovo Approccio per L’educazione Al Patrimonio; Eum: Macerata, Italy, 2014; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Bortolotti, A.; Calidoni, M.; Mascheroni, S.; Mattozzi, I. Per L’educazione al Patrimonio Culturale—22 Tesi; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2008; p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca, J.M. Análisis de concepciones sobre la enseñanza del patrimonio en la educación obligatoria. Enseñanza De Las Cienc. Soc. 2003, 2, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mingozzi, E. Apri una finestra su Bologna: Una esperienza didattica alla scoperta del nostro patrimonio per la costruzione di una cittadinanza attiva. Did. Della Sto.-J. Res. Did. His. 2019, 1, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, N.O. El estudio del patrimonio y las manifestaciones artísticas en la formación inicial. In El Patrimonio y la Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales; Ballesteros, E., Fernández, C., Molina, J.A., Moreno, P., Eds.; Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha: Cuenca, Spain, 2003; pp. 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ávila, R.M. La función de los itinerarios en la enseñanza y el aprendizaje del patrimonio histórico-artístico. Íber. Did. De Las Cien. Soc. Geo. E His. 2003, 36, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Borghi, B. La città come ambiente di apprendimento. Le esperienze del Centro internazionale di Didattica della Storia e del Patrimonio. In Didattica e Ricerca. La Didattica Nella Ricerca e la Ricerca Nella Didattica; Gherardi, V., Ed.; Aracne Editrice: Rome, Italy, 2019; pp. 171–198. [Google Scholar]

- Cajani, L. Le Vicende Della Didattica Della Storia in Italia; New Digital Frontiers: Palermo, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guanci, V.; Rabbiti, M.T. Storia e Competenze nel Curricolo; Mnamon: Milan, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brusa, A.; Musci, E. La didàctica difícil: Els problemes dels límits de l’ensenyament històric. In Les Qüestions Socialment Vives i L’ensenyament de les Ciències Socials; Santisteban, A., Pagés, J., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2011; pp. 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rico, L.; Ávila, R.M. Difusión del patrimonio y educación. El papel de los materiales curriculares. Un análisis crítico. In El Patrimonio y la Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales; Ballesteros, E., Fernández, C., Molina, J.A., Moreno, P., Eds.; Asociación Universitaria de Profesores de Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales-Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha: Cuenca, Spain, 2003; pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Antonaci, A.; Ott, M.; Pozzi, M. Virtual Museums. Cultural heritage education and 21st century skills. Learn. Teach. Med. Tech. 2013, 185, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Estepa, J.; Delgado, E.J. Educación ciudadana, patrimonio y memoria en la enseñanza de la historia: Estudio de caso e investigación-acción en la formación inicial del profesorado de secundaria. REIDICS Rev. De Inv. En Did. De Las Cien. Soc. 2021, 8, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estepa, J.; Martín, M.J. Antipatrimonio y turismo oscuro. El público escolar. PH Boletín Del Inst. Andal. Del Patrim. Histórico 2022, 30, 210–211. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Vera, J.R.; Ponsoda-López de Atalaya, S. La percepción del alumnado sobre la didáctica del patrimonio en la enseñanza de la Historia. In El Compromiso Académico y Social a Través de la Investigación e Innovación Educativas en la Enseñanza Superior; Roig-Vila, R., Ed.; Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca, J.M.; Martín, M.J.; Estepa, J. Buenas prácticas en educación patrimonial: Análisis de las emociones, territorio y ciudadanía. Aula Abierta 2020, 49, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurel, D.; Çetin, T. An Investigation of Secondary School 7th Grade Students’ Awareness for Intangible Cultural Heritage. Online Submiss. 2017, 8, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Molina Puche, S.; Armesto Sancho, A. El patrimonio como elemento de aprendizaje en los viajes educativos de estudiantes estadounidenses en Europa. HerMus. Herit. Mus. 2021, 22, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calaf, R.; Gutiérrez, S.; Suárez, M.Á. Desvelar competencias vinculadas con el conocimiento escolar de las CCSS mediante la evaluación educativa del museo. Ens. De las cien. Soc. Rev. De Inv. 2016, 15, 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Calaf, R.; Fontal, O. (Eds.) Miradas al Patrimonio, 1st ed.; TREA: Asturias, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fontal, O.; Martínez, M.; Ballesteros, T.; Cepeda, J. Percepciones sobre el uso del patrimonio en la enseñanza de la educación artística: Un estudio con futuros profesores de educación primaria. RIFOP Rev. Inter. De Form. Del Profr. 2021, 35, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigwell, K.; Prosser, M.; Taylor, P. Qualitative Differences in Approaches to Teaching First Year University Science. High. Educ. 1994, 27, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, L.; Kember, D. Conceptions of teaching and their relationship to student learning. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1993, 63, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kember, D.; Kwan, K.P. Lecturers’ Approaches to Teaching and Their Relationship to Conceptions of Good Teaching. Instr. Sci. 2000, 28, 469–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigwell, K.; Prosser, M. Development and use of the approaches to teaching inventory. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 16, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J. Calidad del Aprendizaje Universitario, 1st ed.; Narcea: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, C.J.; Chaparro Sainz, Á.; Felices de la Fuente, M.M.; Cózar Gutiérrez, R. Estrategias metodológicas y uso de recursos digitales para la enseñanza de la historia. Análisis de recuerdos y opiniones del profesorado en formación inicial. Aula Abierta 2020, 49, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Romera, C.; Sánchez-Ibáñez, R.; Miralles-Martínez, P. Approaches to History Teaching According to a Structural Equation Model. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, F.; Maquilón, J.; Monroy, F. Estudio de los enfoques de enseñanza del profesorado de educación primaria. Profr. Rev. De Curric. Y Form. Del Profr. 2012, 16, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Monroy, F.; González-Geraldo, J.L.; Hernández-Pina, F. A psychometric analysis of the Approaches to Teaching Inventory (ATI) and a proposal for a Spanish version (S-ATI-20). Anal. Psic. 2015, 31, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ibáñez, R.; Guerrero-Romera, C.; Miralles-Martínez, P. Primary and secondary school teachers’ perceptions of their social science training needs. Hum. Soc. Sci. Comm. 2021, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, M.G.; Cárdenas, F.A.; Hernández-Pina, F. Enfoques de enseñanza y enfoques de aprendizaje: Perspectivas teóricas promisorias para el desarrollo de investigaciones en educación en ciencias. Ciênc. Educ. 2018, 24, 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorno, S.; Ambrosi, L.; Angelini, M. Pensare Storicamente: Didattica, Laboratori, Manuali, 1st ed.; FracoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bertagna, G. Formazione iniziale e reclutamento dei docenti: Nuove basi per una ripartenza. Nuo. Sec. 2020, 1, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Borghi, B.; Dondarini, R. Un Manifesto per la didattica della storia. Didatt. Della Stor.-J. Res. Didact. Hist. 2019, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Musci, E. Patrimonio e didattica, fra teorie e pratiche di cittadinanza. Scu. Ita. Mod. 2015, 5, 85–86. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, H. A interculturalidade em Educação Patrimonial: Desafios e contributos para o ensino de História. Educ. Rev. 2017, 63, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gago, M. Consciência Histórica e Narrativa na aula de História-Concepções de Professores, 1st ed.; Edições Afrontamento: Porto, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Solé, G.; Barca, I. O Manual Escolar no Ensino da História: Visões Historiográficas e Didática, 1st ed.; Associação de Professores de História: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, A. Taking the Perspective of the Other Seriously? Understanding Historical Argument. Educ. Rev. 2011, 42, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H. History in the Primary School: Making Connections across Times and Places through Folk Tales. In Educação Histórica. Ousadia e Inovação em Educação e em História. Escritos em homenagem a Maria Auxiliadora Moreira dos Santos Schmidt, 1st ed.; Urban, A.C., de Rezende, E., Cainelli, M., Eds.; W.A. Editores: Curitiba, Brazil, 2018; pp. 149–167. [Google Scholar]

- Seixas, P.; Morton, T. The Big Six Historical Concepts, 1st ed.; Nelson College Indigenous: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ercikan, K.; Seixas, P. Issues in Designing Assessments of Historical Thinking. Theory Pract. 2015, 54, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorp, R.; Persson, A. On historical thinking and the history educational challenge. Educ. Philos. Theory 2020, 52, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanSledright, B.A. Assessing Historical Thinking and Understanding. Innovation Design for New Standards, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wineburg, S. Why Learn History (When it Is Already on Your Phone), 1st ed.; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yunga, D.C.; Loaiza Aguirre, M.I.; Ramón, L.N.; Bravo, L. Enfoques de la Enseñanza en Educación Universitaria: Una exploración desde la perspectiva Latinoamericana. Profr. Rev. De Curric. Y Form. Del Profr. 2016, 20, 313–333. [Google Scholar]

- Miralles, P. Estado de la cuestión sobre la didáctica de la Historia en España. In Canteiro de Histórias: Textos Sobre Aprendizagem Histórica; Bueno, A., Crema, D.E., Neto, J.M., Eds.; Edição Especial Ebook LAPHIS/Sobre Ontens: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2017; pp. 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cercadillo, L.; Chapman, A.; Lee, P. Organizing the past: Historical accounts, significance and unknown ontologies. In Palgrave Handbook of Research in Historical Culture and Education, 1st ed.; Carretero, M., Berger, S., Grever, M., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2017; pp. 529–552. [Google Scholar]

- Challenor, J.; Ma, M. A review of augmented reality applications for history education and heritage visualisation. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2019, 3, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P. Historical literacy and transformative history. Edu. Em Rev. 2016, 60, 107–146. [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque, S.; Croteau, J.P. Beyond History for Historical Consciousness. Students, Narrative & Memory, 1st ed.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Van Drie, J.; Van Boxtel, C. Historical reasoning: Towards a framework for analyzing student’s reasoning about the past. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 20, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchán, F.J. El control de la conducta del alumnado en el Aula. ¿Un problema para la práctica de la investigación escolar? Investig. En La Esc. Rev. De Investig. E Innovación Esc. 2011, 73, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, P.M.; Carrasco, C.J.G. Sin «Cronos» ni «Kairós». El tiempo histórico en los exámenes de 1.° y 2.° de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Enseñanza De Las Cienc. Soc. Rev. De Investig. 2016, 15, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáiz, J.; Gómez, C.J. Investigar el pensamiento histórico y narrativo en la formación del profesorado: Fundamentos teóricos y metodológicos. Rev. Electrónica Interuniv. De Form. Del Profr. 2016, 19, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hita, M.M.; Carrasco, C.J.G. Nivel cognitivo y competencias de pensamiento histórico en los libros de texto de Historia de España e Inglaterra. Un estudio comparativo. Rev. De Edu. 2018, 379, 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, C.J.; Ortuño, J.; Miralles, P. Enseñar Ciencias Sociales con Métodos Activos de Aprendizaje. Reflexiones y Propuestas a Través de la Indagación, 1st ed.; Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Verdú, D.; Guerrero, C.; Villa, J.L. ; Pensamiento Histórico y Competencias Sociales y Cívicas en Ciencias Sociales, 1st ed.; EDITUM: Murcia, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Montilla-Coronad, M.V.C.; Maraver-López, P.; Oliva, C.R.; Montilla, A.M. Análisis de las expectativas del profesorado novel sobre su futura labor docente. Aula Abierta 2018, 47, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejene, W.; Bishaw, A.; Dagnew, A. Preservice Teachers’ Approaches to Learning and Their Teaching Approach Preferences: Secondary Teacher Education Program in Focus. Cogent Educ. 2018, 5, 1502396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braslavsky, C. Diez factores para una educación de calidad para todos en el siglo XXI. REICE Rev. Electrónica Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Y Cambio En Educ. 2006, 4, 84–101. [Google Scholar]

- Postareff, L.; Katajavuori, N.; Lindblom-Ylänne, S.; Trigwell, K. Consonance and Dissonance in Descriptions of Teaching of University Teachers. Stud. High. Edu. 2008, 33, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felini, D. Quality media literay education. A tool for teachers educators of Italian Elementary Schools. J. Med. Lit. Edu. 2014, 6, 28–43. [Google Scholar]

- Orts, M. El uso de móviles en el instituto. Reflexiones en el instituto Jaume Vicens Vives (Girona). Aula De Secund. 2019, 32, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Olmos, R. Kahoot: ¡Un, dos, tres! Análisis de una aplicación de cuestionarios. Íber Didáctica De Las Cienc. Soc. Geogr. E Hist. 2017, 86, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, R.J. Experimentación y Análisis del uso de los Videojuegos para la Educación Patrimonial. Estudio de caso en 1.o de ESO, 1st ed.; Universidad de Huelva: Huelva, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rivero, P.; Feliu, M. Aplicaciones de la arqueología virtual para la Educación Patrimonial: Análisis de tendencias e investigaciones. Estud. Pedagóg. 2017, 43, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, F. Del juego a la gamificación. Mitos y leyendas de las TIC. Aul. De Innov. Educ. 2017, 267, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Calviño, L.C.; Medina, J.R.; Carrasco, C.J.G.; López-Facal, R. Patrimonializarte: A heritage education program based on new technologies and local heritage. Edu. Sci. 2020, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, A.E. Manual para el desarrollo de proyectos educativos de museos. Edu. Sig. XXI 2015, 33, 347–350. [Google Scholar]

| Items | Start | Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| 9.1 | 1.000 | 0.762 |

| 9.2 | 1.000 | 0.867 |

| 9.3 | 1.000 | 0.736 |

| 9.4 | 1.000 | 0.787 |

| 9.5 | 1.000 | 0.727 |

| 9.6 | 1.000 | 0.846 |

| 9.7 | 1.000 | 0.757 |

| 9.8 | 1.000 | 0.794 |

| 9.9 | 1.000 | 0.883 |

| 9.10 | 1.000 | 0.672 |

| 10.1 | 1.000 | 0.680 |

| 10.2 | 1.000 | 0.614 |

| 10.3 | 1.000 | 0.338 |

| 10.4 | 1.000 | 0.673 |

| 10.5 | 1.000 | 0.793 |

| 10.6 | 1.000 | 0.763 |

| 10.7 | 1.000 | 0.764 |

| 10.8 | 1.000 | 0.734 |

| 10.9 | 1.000 | 0.736 |

| 10.10 | 1.000 | 0.861 |

| 11.1 | 1.000 | 0.716 |

| 11.2 | 1.000 | 0.758 |

| 11.3 | 1.000 | 0.700 |

| 11.4 | 1.000 | 0.665 |

| 11.5 | 1.000 | 0.690 |

| 11.6 | 1.000 | 0.665 |

| 11.7 | 1.000 | 0.757 |

| 11.8 | 1.000 | 0.853 |

| 11.9 | 1.000 | 0.902 |

| 11.10 | 1.000 | 0.670 |

| 11.11 | 1.000 | 0.753 |

| 11.12 | 1.000 | 0.603 |

| 12.1 | 1.000 | 0.743 |

| 12.2 | 1.000 | 0.766 |

| 12.3 | 1.000 | 0.869 |

| 13.1 | 1.000 | 0.593 |

| 13.2 | 1.000 | 0.599 |

| 13.3 | 1.000 | 0.649 |

| 13.4 | 1.000 | 0.485 |

| Factor | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.406 | 30.962 | 30.962 | 2.889 | 26.266 | 26.266 | 2.816 |

| 2 | 2.030 | 18.450 | 49.412 | 1.526 | 13.876 | 40.142 | 1.481 |

| 3 | 1.206 | 10.962 | 60.374 | 0.770 | 7.000 | 47.141 | 1.215 |

| 4 | 0.902 | 9.109 | 69.483 | ||||

| 5 | 0.842 | 7.657 | 77.139 | ||||

| 6 | 0.630 | 5.731 | 82.871 | ||||

| 7 | 0.602 | 5.472 | 88.343 | ||||

| 8 | 0.393 | 3.577 | 91.920 | ||||

| 9 | 0.384 | 3.492 | 95.412 | ||||

| 10 | 0.261 | 2.370 | 97.782 | ||||

| 11 | 0.244 | 2.218 | 100.000 |

| Items | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9.1 | −0.021 | 0.578 | −0.352 |

| 9.2 | 0.856 | −0.117 | −0.088 |

| 9.3 | 0.194 | 0.573 | −0.397 |

| 9.4 | 0.836 | 0.030 | 0.005 |

| 9.5 | 0.679 | −0.363 | −0.108 |

| 9.6 | 0.876 | −0.246 | 0.014 |

| 9.7 | 0.818 | −0.235 | 0.134 |

| 9.8 | 0.771 | −0.287 | 0.282 |

| 9.9 | 0.725 | −0.408 | 0.275 |

| 9.10 | 0.807 | −0.126 | 0.059 |

| 10.1 | −0.308 | 0.484 | −0.164 |

| 10.2 | 0.723 | 0.004 | −0.193 |

| 10.3 | 0.464 | 0.008 | −0.428 |

| 10.4 | 0.573 | −0.170 | −0.524 |

| 10.5 | 0.831 | 0.004 | −0.125 |

| 10.6 | 0.659 | 0.016 | −0.085 |

| 10.7 | 0.683 | −0.124 | −0.468 |

| 10.8 | 0.755 | −0.382 | 0.078 |

| 10.9 | 0.251 | 0.687 | −0.185 |

| 10.10 | 0.583 | −0.381 | −0.277 |

| 11.1 | 0.449 | −0.565 | −0.084 |

| 11.2 | −0.243 | −0.217 | 0.569 |

| 11.3 | −0.136 | −0.168 | 0.648 |

| 11.4 | 0.385 | −0.243 | 0.646 |

| 11.5 | 0.775 | 0.142 | −0.002 |

| 11.6 | −0.017 | 0.586 | −0.014 |

| 11.7 | 0.561 | −0.225 | 0.531 |

| 11.8 | 0.744 | 0.047 | 0.380 |

| 11.9 | 0.391 | −0.579 | 0.330 |

| 11.10 | −0.108 | −0.289 | 0.483 |

| 11.11 | 0.818 | 0.249 | 0.144 |

| 11.12 | 0.285 | −0.042 | 0.575 |

| 12.1 | 0.030 | 0.702 | −0.196 |

| 12.2 | −0.032 | −0.333 | 0.676 |

| 12.3 | 0.703 | 0.147 | 0.007 |

| 13.1 | 0.011 | −0.223 | 0.618 |

| 13.2 | 0.463 | 0.205 | 0.283 |

| 13.3 | 0.389 | 0.587 | −0.111 |

| 13.4 | 0.215 | 0.071 | 0.563 |

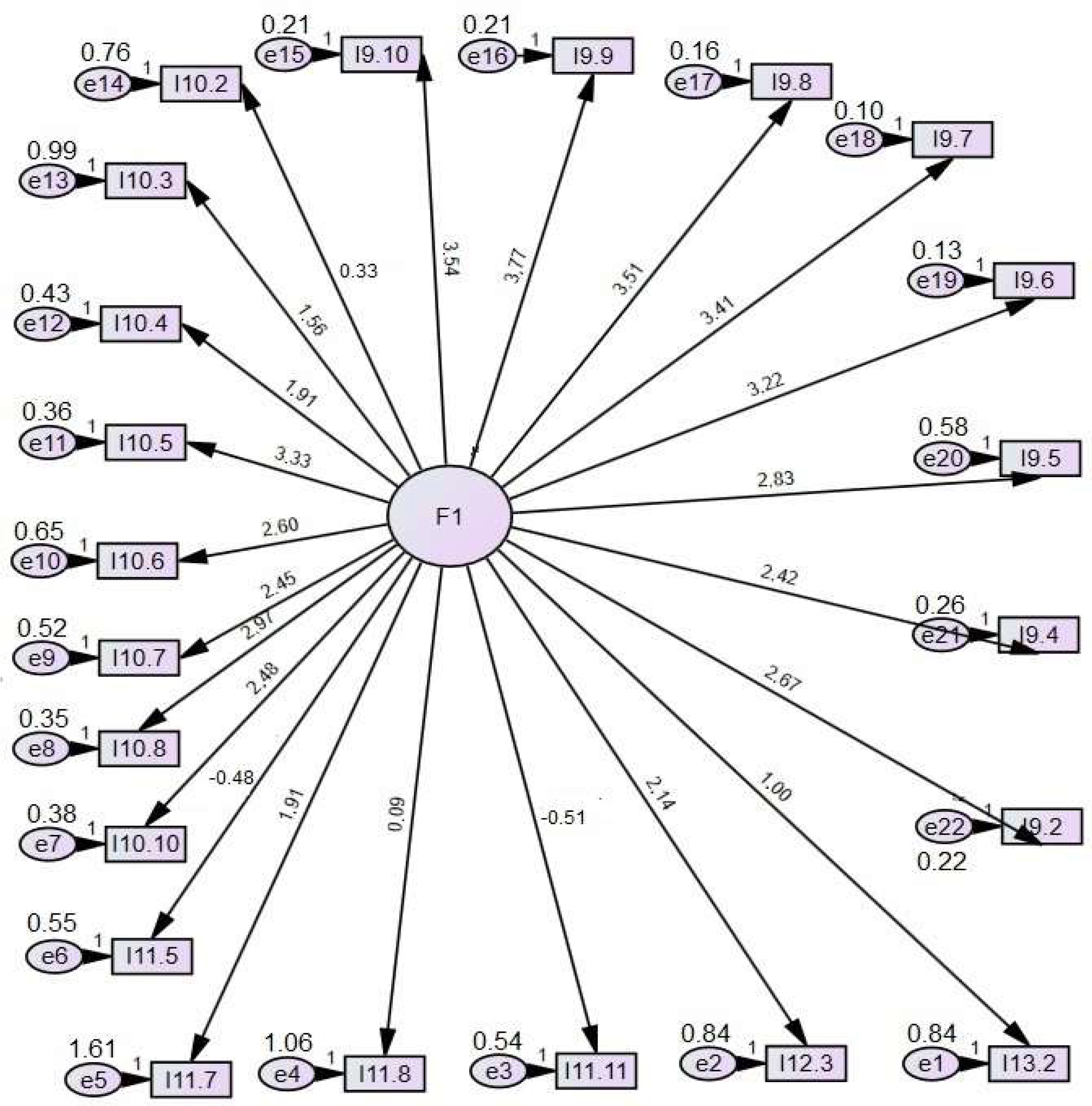

| Item | Question | Answer Option |

|---|---|---|

| 9.2 | How often do you teach the following content and skills to your students through heritage? | Teaching analysis from primary sources |

| 9.4 | How often do you teach the following content and skills to your students through heritage? | Teaching change and continuity of historical processes |

| 9.5 | How often do you teach the following content and skills to your students through heritage? | Teaching the historical relevance of characters and events |

| 9.6 | How often do you teach the following content and skills to your students through heritage? | Explaining the ethical dimension of historical facts |

| 9.7 | How often do you teach the following content and skills to your students through heritage? | Teaching understanding the past with a historical perspective |

| 9.8 | How often do you teach the following content and skills to your students through heritage? | Teaching historical discourse (historical method) |

| 9.9 | How often do you teach the following content and skills to your students through heritage? | Linking the past with the present |

| 9.10 | How often do you teach the following content and skills to your students through heritage? | Teach historical awareness: explain conflicting issues through heritage |

| 10.2 | How much do you use the following teaching strategies to teach heritage? | Flipped classroom |

| 10.3 | How much do you use the following teaching strategies to teach heritage? | Role-playing |

| 10.4 | How much do you use the following teaching strategies to teach heritage? | Debates |

| 10.5 | How much do you use the following teaching strategies to teach heritage? | Problem-based learning |

| 10.6 | How much do you use the following teaching strategies to teach heritage? | Project-based learning |

| 10.7 | How much do you use the following teaching strategies to teach heritage? | Research |

| 10.8 | How much do you use the following teaching strategies to teach heritage? | Teaching how to analyze sources |

| 10.10 | How much do you use the following teaching strategies to teach heritage? | Collaborative learning |

| 11.5 | How often do you use the following teaching resources to teach heritage? | Videogames |

| 11.7 | How often do you use the following teaching resources to teach heritage? | Virtual tours or multimedia resources |

| 11.8 | How often do you use the following teaching resources to teach heritage? | Educational mobile applications |

| 11.11 | How often do you use the following teaching resources to teach heritage? | Games |

| 12.3 | How often do students do the following types of activities in class? | Activities that help to understand heritage as a primary source for the elaboration of a historical narrative about the past at a higher cognitive level |

| 13.2 | How do you assess your students’ learning of heritage? | Through the practical work I design |

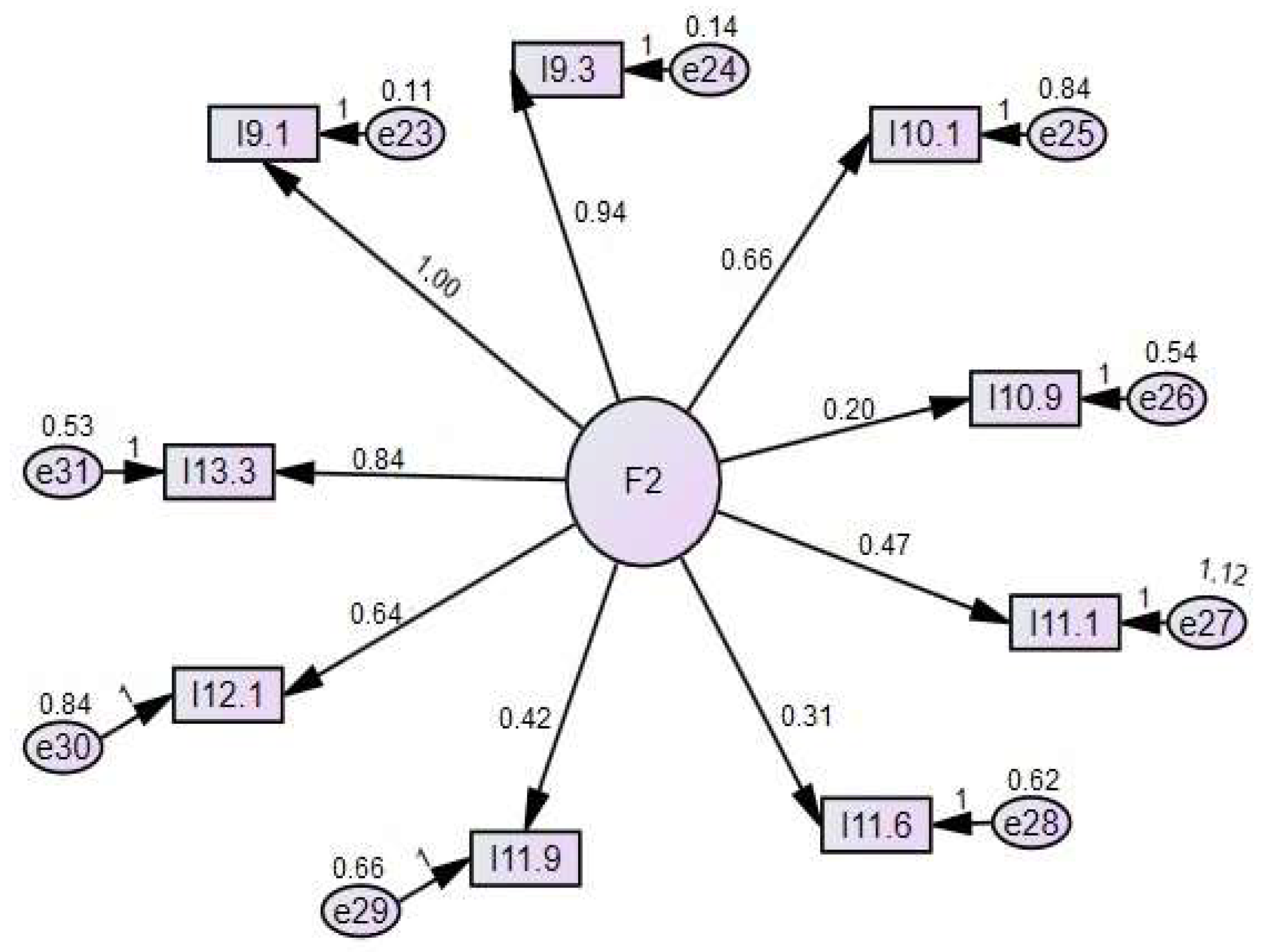

| Item | Question | Answer Option |

|---|---|---|

| 9.1 | How often do you teach the following content and skills to your students through heritage? | Teaching knowledge (theoretical content) |

| 9.3 | How often do you teach the following content and skills to your students through heritage? | Teaching multicausality and the consequences of facts |

| 10.1 | How much do you use the following teaching strategies to teach heritage? | Masterclass |

| 10.9 | How much do you use the following teaching strategies to teach heritage? | Autonomous and individual learning |

| 11.1 | How often do you use the following teaching resources to teach heritage? | History textbook |

| 11.6 | How often do you use the following teaching resources to teach heritage? | Guided tours (museums, archaeological sites, etc.) |

| 11.9 | How often do you use the following teaching resources to teach heritage? | Photographs |

| 12.1 | How often do students do the following types of activities in class? | Activities to describe the basic characteristics of heritage |

| 13.3 | How do you assess the students’ learning of heritage? | Final written test |

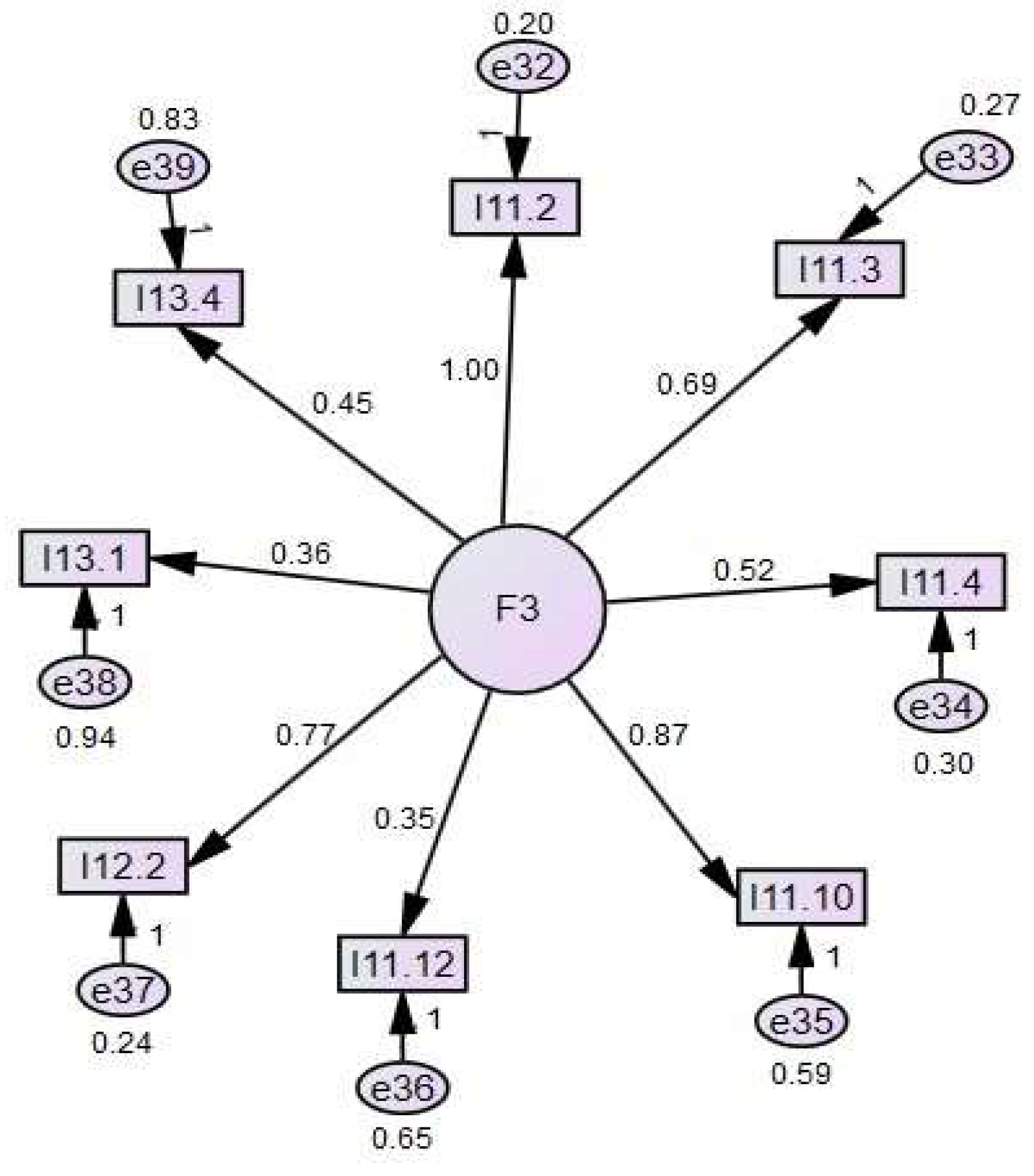

| Item | Question | Answer Option |

|---|---|---|

| 11.2 | How often do you use the following teaching resources to teach heritage? | Specific books on heritage |

| 11.3 | How often do you use the following teaching resources to teach heritage? | Films |

| 11.4 | How often do you use the following teaching resources to teach heritage? | Documentaries |

| 11.10 | How often do you use the following teaching resources to teach heritage? | Oral sources |

| 11.12 | How often do you use the following teaching resources to teach heritage? | Workshops |

| 12.2 | How often do students do the following types of activities in class? | Activities to understand the heritage element by contextualizing it in its spatial and temporal coordinates (intermediate cognitive level) |

| 13.1 | How do you assess the students’ learning of heritage? | Through the exercises in the textbook |

| 13.4 | How do you assess the students’ learning of heritage? | Through a written test (questionnaire) |

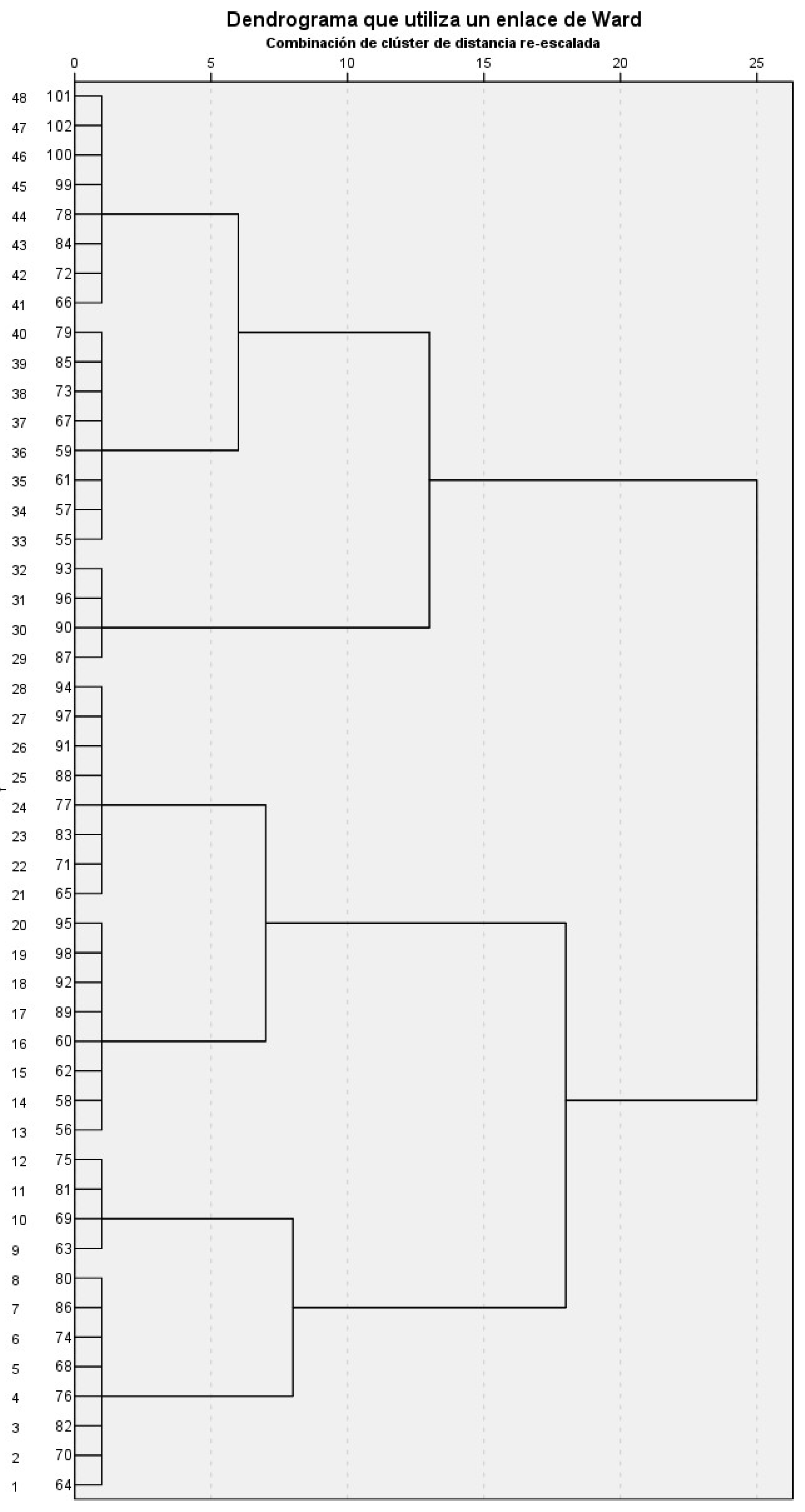

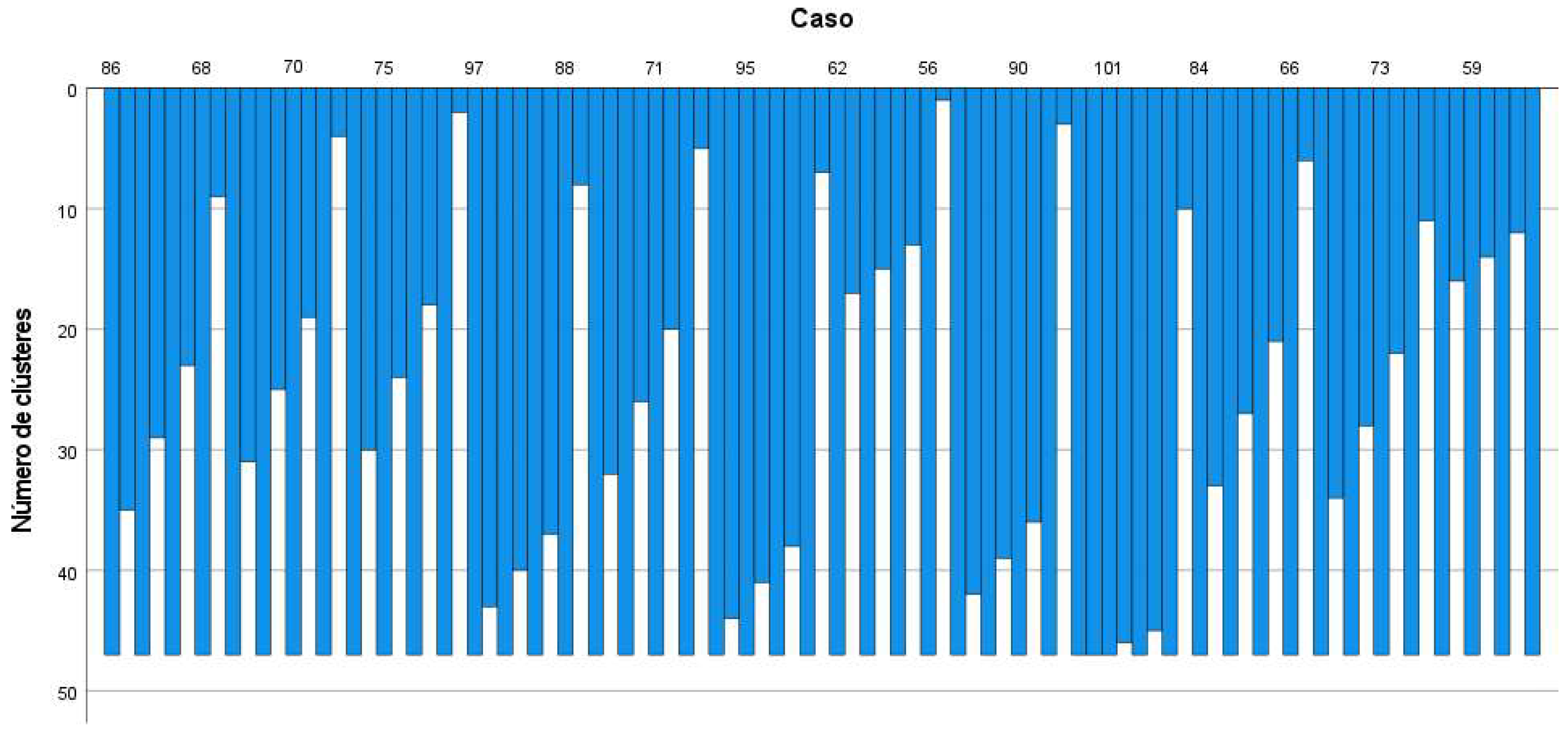

| Average Linkage (Between Groups) | REGR Factor Score 1 for Analysis 1 | REGR Factor Score 2 for Analysis 1 | REGR Factor Score 3 for Analysis 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N | Valid | 58 | 58 | 58 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Mean | 0.0077341 | 0.0178238 | −0.0673052 | ||

| Standard dev. | 0.92700789 | 0.89030283 | 0.81018227 | ||

| 2 | N | Valid | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Mean | 0.3018193 | −0.5470886 | 1.5282909 | ||

| Standard dev. | 0.17188340 | 0.37138275 | 0.25182663 | ||

| 3 | N | Valid | 21 | 21 | 21 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Mean | −1.4623146 | 0.3579488 | 0.2611032 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Ibáñez, R.; Cimino, A. Validation of an Instrument on Perceptions of Heritage Education through Structural Equation Modeling. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6865. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086865

Sánchez-Ibáñez R, Cimino A. Validation of an Instrument on Perceptions of Heritage Education through Structural Equation Modeling. Sustainability. 2023; 15(8):6865. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086865

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Ibáñez, Raquel, and Alfonso Cimino. 2023. "Validation of an Instrument on Perceptions of Heritage Education through Structural Equation Modeling" Sustainability 15, no. 8: 6865. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086865

APA StyleSánchez-Ibáñez, R., & Cimino, A. (2023). Validation of an Instrument on Perceptions of Heritage Education through Structural Equation Modeling. Sustainability, 15(8), 6865. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086865