Abstract

This research was undertaken with the objective of relating entrepreneurial perceived behaviour (EPB) and entrepreneurial intentions (EI) with students’ perceptions of the United Nations sustainable development goals. The current research advances on from EPB and EI to analyse whether the study of entrepreneurial competencies (ECs) enhance the impact of EI on sustainable growth. Sustainable growth is measured through the perception of students regarding the United Nations SDGs, measured through SDG3, SDG8, SDG9, and SDG10. Earlier studies have linked EPB with EIs as entrepreneurship, in the long run, has to focus on sustainable growth. EPB comprises entrepreneurial attitude, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms. ECs comprise leadership skills (LS); risk-taking skills (RTS); opportunity identification skills (OIS); perseverance skills (PS); and societal skills (SS). The study is based on a survey with data collected through a structured questionnaire from 480 engineering students. SEM-PLs was used to analyse the results. The outcomes suggest a direct relationship between EPB and EI, and EI and sustainable growth. However, as the main objective of the study was to find whether ECs enhance the impact of EIs with respect to ECs on sustainable growth, the results provide empirical support for EM-EI(ECs)-SG as there is a positive and significant indirect effect, suggesting complementary action, thus validating the proposed theoretical sustainable growth (SG). These outcomes suggest that there is a need to focus on ECs to improve the impact of EIs on SG.

1. Introduction

During the last two decades, sustainable development has gained a lot of importance. Entrepreneurship is recognized as a major driver for achieving sustainable growth and solving the challenges of sustainable development [1]. A systematic study of how Aizen’s theory of planned behaviour control (PBC) with entrepreneurial intention could be relevant in achieving sustainable growth especially in view of entrepreneurial education by higher educational institutions (HEIs) [2]. Empirical studies have extensively examined the impact of these direct determinants on entrepreneurial intentions, and there is a growing need to explore additional factors that can account for such intentions [3,4,5]. Sustainable growth includes: SDG3, ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all ages; SDG8, promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all; SDG9, build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation; and SDG10, reduce inequality within and among countries. SDG3, SDG8, and SDG9 are directly or indirectly linked when using entrepreneurship and innovation as a means to achieving sustainable growth. SDG10 is linked to governmental policies in promoting entrepreneurial culture in their country to promote a culture of innovative[6].

Earlier literature has focused on relating entrepreneurial behaviour and entrepreneurial intentions. Some researchers have suggested its relevance in HEIs leading to the introduction of EE. However, as highlighted by Nowiński et al. [7] and Taneja et al. [8], if we want to build EIs into students, there must be a focus on experiential learning. In this study we want to extend this further and see which competencies [9] help achieve sustainable growth, measured through SDG3, SDG8, SDG9, and SDG10. Entrepreneurial behaviour translated into ES must cater to these four SDGs to build innovative organizations, and promote health and well-being for sustained industrialization and growth. The present research is an effort in this direction, in addition it also considers the mediating role of entrepreneurial competencies to achieve sustainable growth.

- RQ1:

- How is EPB related with EIs?

- RQ2:

- Are EIs directly related with sustainable growth when measured through SDG3, SDG8, SDG9, and SDG10?

- RQ3:

- Is sustainable growth, when measured through SDG3, SDG8, SDG9, and SDG10, enhanced if EIs are pre-empted with ECs?

- RQ4:

- How are entrepreneurial behaviours, EIs and ECs related to sustainable growth when measured through SDG3, SDG8, SDG9 and SDG10.

2. Theoretical Underpinning and Hypotheses Development

The entrepreneurial literature is burgeoning with the prominent and conspicuous role played by entrepreneurial behaviour [10]. Entrepreneurial behaviour and perceived behaviour control have strong influence over entrepreneurial intentions (EIs), with the subjective norms and theory of planned behaviour as important aspects in explaining the relationship [11]. Entrepreneurial perceived behaviour (EPB) refers to the attitudes and beliefs that can have a significant effect on people to pursue entrepreneurship [12]. Additionally, the vibrant role of entrepreneurs in attaining sustainable development goals (SDGs) has also been reflected in many recent studies. Entrepreneurship through the creation of new businesses will help provide employment, reduce inequality, diminish poverty, and promote sustainable growth. The governments in developing economies are fast realizing the potential of entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship [13]. This interest is evident in the rapid development of entrepreneurship curricula and education programs since the early 80s. This has led to an increased in providing entrepreneurial education (EE) in higher educational institutions (HEIs). EE helps to shape entrepreneurial perceived behaviours and higher levels of education are more likely to relate with entrepreneurship as a viable career option [14].

A recent study by Taneja et al. [8] has suggested that we need to focus not on EE in general but experiential learning in entrepreneurship. With this is mind, in this study the major focus is on entrepreneurial competencies, which may be provided through business incubators (BIs) and entrepreneur development cells (EDCs) in HEIs. In addition to the theory of planned behaviour (TPB), other theories, such as social cognitive theory, self-determination theory, and resource-based theory, can be used to explain the relationship between entrepreneurial perceived behaviour (EPB) and entrepreneurial intentions (EIs). These theories differ in terms of the specific factors they emphasize and the mechanisms they propose to explain [15,16,17]. The study aims to apply the TPB to analyse the effect of EPB on EIs. Further, this study aims to examine the action of ECs between EI and sustainable growth (SG) when measured through SDG3, SDG8, SDG9 and SDG10. A current study by Ashari et al. [18] has suggested that attending entrepreneurship courses does not increase the strength of the association between EB and EI, thus indicating the need to improve course curricula and teaching pedagogy. This limitation has helped us to frame this study to focus on ECs in addition to EB and EI in our ultimate role to stimulate SG.

Entrepreneurship has been recognized as a critical factor in promoting economic growth and addressing global challenges. However, personal traits alone may not be sufficient to foster EIs. Recent studies have shown that entrepreneurial education (EE) plays a crucial role in cultivating positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship. Some studies, however, suggest a weak or negative relationship between EE and EI [5,19]. Management practices have also been found to positively impact entrepreneurial behaviour. EE based on successful entrepreneurial role models has been shown to positively influence EIs [20,21]. Despite the declining outcomes of EE reported in earlier literature [22], recent research indicates that choosing entrepreneurship as a major leads to higher EIs and a greater likelihood of venture creation [23,24].

2.1. Entrepreneurial Perceived Behaviour (EPB)

India is an emerging economy and the government wants to encourage a start-up culture [25,26,27]. The Atal Innovation Mission is the Indian Government’s flagship initiative to promote entrepreneurship by providing funding to educational institutions to start business incubators [28]. Su et al. [29] advocated that positive emotions significantly influence entrepreneurial motivation (EM). Bartha et al. [30] report that social mission as an important factor influencing EM. Hemmert et al. [31] ascertained that EM helps to initiate new ventures. Hessels et al. [32] established that self-employed people are generally presumed to be less stressed. EE assists in improving entrepreneurial skills and ECs [33]. Citing the theory of planned behavior (TPB), Bosnjak et al. [10] suggested that the most important determinant of an individual’s behaviour is their intention to perform that behaviour with three cognitive variables—attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control—said to be the direct determinants of intention. Research has shown attitudes predict both intention and behaviour [34].

Prior literature advocates that perceived entrepreneurship behaviour correlates with entrepreneurial attitudes (EA), subjective norms (SN), and perceived behavioural control (PBC) [10,35,36]. A difference is observed regarding the influence of the subjective norms of EPB on EI; however, as pointed by Bosnjak et al. [10], the correct scale of intention suggests a strong relationship of norms with EI. PEB EPB is impacted by social appraisal and sustenance [37,38]. Gerba [39] revealed that students with EE are more inclined to possess better EIs. It is important to see how this may be relevant for engineering graduates. With technical expertise, engineering graduates with EPB may be more suitable to be successful entrepreneurs. In view of this it is important to link EE, EI and SG when measured through the related SDGs. The outcomes of the research by Lu et al. [40] indicated that attitudes have a deeper association with intentions when attitudes mediate self-efficacy and intentions. EI is a person’s belief in initiating a new venture and their determination to execute their plan [41]. Researchers have proven that EI helps to explain the variation in entrepreneurship [42]. Researchers, such as Pérez-Pérez et al. [43], and Rashid [44], maintain that EI is due to internal and external motivation [45].

This present research uses the theory of planned behaviour (TPB), covering the strong desire and engagement towards entrepreneurship. The intrinsic factors include a person’s attitude, SN, and PBC which consequently influence their EIs [46]. Kim-Soon et al. [47], indicated PBC, SN, and attitude as the sub-constructs of motivation. EM had a substantial influence on the EIs of Malaysian university students. The present research allies with other similar studies relating attitude, PBC, SN with EI [24,48,49]. Further support has been reported by Dinc and Budic [50], indicating that PBC and personal attitude influenced individual’s intent to become involved in entrepreneurial events. The outcomes of the study by Ambad and Damit [51] highlighted personal attitude, perceived behavioural control, and perceived relational support as predictors of entrepreneurial intention. Similar findings were reported by Mutlutürk and Mardikyan [52]. Results from Jr. and Akiate [53] supported that PBC and personal attitude had a positive influence on EI.

H1:

Entrepreneurial perceived behaviour is a multidimensional construct consisting of entrepreneurial attitude, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms.

2.2. Entrepreneurial Competencies

Herrmann et al. [54] advocated for experiential education to provide students with entrepreneurial skills to empower them to search for a solution to real-world problems. The authors of Seun and Kalsom [55] along with Cheraghi and Schøtt [56] concluded that EI augments knowledge, skills and increases ECs. Engineering graduates need communication skills, leadership traits, and marketing skills for new product development [57]. SCORE, a successful US community economic development program, provides essential training for starting a small business. A comparison of the SCORE skill dimensions with prominent practice-based models highlight its uniqueness [58]. Providing entrepreneurial skills to students will help develop an entrepreneurial culture will help them become job providers and assist in the country’s development. It is important to highlight which entrepreneurial skills are critical. Ref. Schumpeter [59] related the success of entrepreneurship with risk-taking abilities and an innovative mindset. Gundry et al. [60] emphasised that creativity positively influence perceptions for innovation and its outcomes. Ref. Miller [61] suggested that entrepreneurial training helps in increasing risk-taking abilities and improves innovativeness. Ref. Wickham [62] elaborated with a focus on market innovations. Huber et al. [63] suggested an emphasis on robust non-cognitive entrepreneurial skills. Ref. Gaglio and Katz [64] suggested that what is risk some people, may be seen as an opportunity by an entrepreneur. This was also supported by Shook et al. [65], Chatterjee and Das [66], who highlighted the importance of these skills on the success of micro-entrepreneurs. Römer-Paakkanen and Pekkala [67] emphasized the importance of learning by experience and problem-solving for HEI students and reported that these skills motivated them towards entrepreneurship.

The framework by Loué and Baronet [68] focused on 44 skills classified into eight groups: (a) Intuition and vision; (b) opportunity recognition and exploitation; (c) financial management; (d) human resource management; (e) marketing and communication activities; (f) leadership; (g) self-discipline; and (h) marketing and monitoring. Thus, as highlighted through earlier studies, there is a necessity for entrepreneurship training to develop the skills needed for being a successful entrepreneur [69,70,71]. Ajzen [46] highlighted that a person will be able to accomplish success if they are able to regulate endogenic/exogenic factors. Training through business incubators to provide candidates who are EC is essential to venture, organize and manage an enterprise proficiently and also realize the objectives of the business venture. We have identified five skills: leadership (LS) and risk-taking(RTS); opportunity identification (OIS); perseverance (PS); and societal (SS). These competencies help to augment competitiveness, recognise opportunities, understand market dynamism, and realize the goals of the enterprise. These competencies may be latent and triggered through proper training. The related hypothesis is:

H2:

Entrepreneurial competencies comprise leadership skills (LS) and risk-taking skills (RTS), opportunity identification skills (OIS), perseverance skills (PS), and societal skills (SS).

2.3. Linking PEB; EI and ECs with SG through SDG3, SDG8, SDG9, and SDG10

Kolvereid and Øystein Moen [72] concluded that majors in entrepreneurship helped acquire higher EIs and thus more inclined to create new business ventures. Moses et al. [73] stated that intentions directed a person towards defined goals. According to Liñán et al. [74] if a person wants to achieve something in life, intentions play very vital role. Maresch et al. [75] examined the effect of EIs by EE among science, engineering and business students in the Netherlands. They suggested that TPB affected EIs. However, the researchers suggested that all EIs may not translate into initiating and running a new venture. Entrepreneurial family, age and the academic environment in the institute have a positive effect in translating intentions into start-ups. This was more evident in males students. Shirokova et al. [76] regarded EIs as the first step in entrepreneurship. In view of the ongoing research, it is important to examine how EPB influences the EIs of engineering graduates. EI models suggest that entrepreneurship is a planned, volitionally controlled behaviour that is inherently intentional rather than instinctive. According to Yan et al. [77], relating EE with EI using the TPB indicated that students’ EI scores rose significantly after participating in EE.

Prior literature on venture success in terms of sustainable growth (SG) has dealt with economic indicators [78,79,80]. Different studies have reported financial metrics [81]; sales [82]; market position [83]; and productive improvement [84] to be related with ES. However, Kiviluoto [79] suggested to not solely trust economic metrics. Further, Gorgievski et al. [78] related satisfaction with business performance. The success metric used should cover a holistic perspective. Along with profit and company growth, entrepreneurs need to use other measures for gauging venture success. Andruszkiewicz et al. [85] suggested a shift from financial perspectives to include the stakeholders’ perspective. Organizational performance, as per Richard et al. [83], comprises financial performance (profits, ROI), market performance (sales, share in market), and shareholder benefit (return, value added). Thus, keeping this as the base, it can be inferred that success should include both economic and shared perceptions, including stakeholder satisfaction, public perception, reputation, and fulfilment of social needs [80,83,85,86]. Some studies highlight these proficiencies Ajzen [46], Holienka et al. [87]. On the contrary, there is limited literature examining which competencies are needed to stimulate the influence of EI on SG. The responsibility of EE is to teach entrepreneurial skills and change the mindset of prospective entrepreneurs. Promoting an entrepreneurial culture is not enough, focusing on which competencies help in sustained growth is the major motivation of this paper. Entrepreneurship can help drive innovations, through knowledge spill-overs, increased competition, and increased businesses variety Fritsch and Mueller [88]. As highlighted by Stoica et al. [89], opportunity-driven entrepreneurship has a greater impact in transition nations compared to necessity-driven entrepreneurship in innovation-driven economies. Doran et al. [90] revealed the positive impact entrepreneurial attitudes have on GDP per capita in high-income nations, while a reverse effect was observable in low-income economies. In view of this, it would be good to examine how EI is linked with sustainable growth. Hence from the debate cited above, the current research is channelled through the following hypotheses:

H3:

Perceived entrepreneurial behaviour has a positive and significant influence on EI.

H4:

EI has a positive and significant influence on sustainable growth when measured through SDG3, SDG8, SDG9, and SDG10.

Further, whether ECs mediate EIs and SG needs to be considered.

H5:

ECs mediate EI and sustainable growth when measured through SDG3, SDG8, SDG9, and SDG10.

The final hypothesis is:

H6:

Perceived entrepreneurial behaviour and EI (mediated by ECs) have a positive and significant influence on sustainable growth when measured through SDG3, SDG8, SDG9, and SDG10.

The proposed relationship is depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Proposed relation.

3. Research Design and Methods

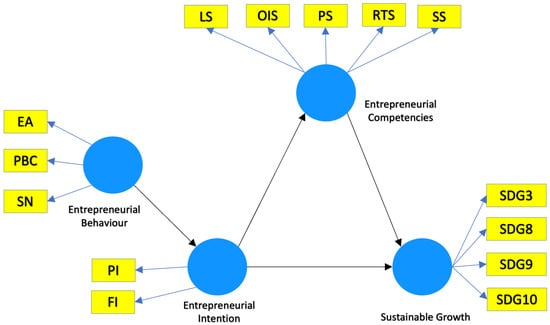

The proposed model is shown in Figure 1. The present research covers ECS as an added mediating variable among EI and SG. The research analyses the combined indirect effect of EPB on EI and EI with ECs on SG. Table 1 presents the suggested model and relationships among the selected constructs.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model.

3.1. Sample

The study used convenience sampling as it is recognised to be sufficient in the case of an entrepreneurial sample [7]. First, the top 100 ranking institutions in the National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF) were selected. From these 100 institutions, only HEIs providing entrepreneurship courses/programs were included, possessing entrepreneurial development cells (EDC), business incubation (BI) or both. Thus, six public and six private institutions were chosen in selected region of Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh. Data were gathered using a convenience sample of 480 engineering students. The student sample was used as this research deals with the EIs of ‘potential entrepreneurs’, as suggested by Kickul et al. [91]. The target was 40 responses from each institution. Data were collected in two phases, phase 1, from 1 June 2019 to 30 August 2020, and phase 2, from September 2020 to October 2021. In phase 1, the responses were slow; therefore, in the subsequent phase respondents were also contacted through electronic media to increase the response rate.

3.2. Scales

The EM metric was adopted from the previous studies of Gerba [39], Ajzen [46], Brandstätter [84] and Okpara [92]. EPB had three sub-constructs: EA, PBC and SN. The study used the EI metric from Linán and Chen [93] covering present and future intentions with a few items from Maresch et al. [75] and Shirokova et al. [76]. The EC metric was self-constructed with items borrowed from Chatterjee and Das [66] and Loué and Baronet [68]. The items were validated through a pilot survey and expert input (faculty and mangers of business incubators in these institutions). The details of the questionnaire are included in Appendix A. The sustainable growth metric was also self-constructed with a focus on SDG, ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all ages; SDG8, promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all; SDG9, build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation; and SDG10, reduce inequality within and among countries. The major idea was to identify how engineering students perceive EIs through ECs in helping move towards sustainable growth through the selected SDGs. Entrepreneurial success can only be gauged if sustained.

3.3. Research Methods

Partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) is an alternative to CB-SEM [94], which has many restrictive assumptions as suggested by [95]. PLS-SEM combines principal components analysis with ordinary least squares regressions [96]. While CB-SEM (AMOS) is covariance-based, PLS-SEM is variance-based. The latter applies total variance to estimate parameters, thus leading to its increasing acceptance among researchers [95,97,98]. As the current research is based on numerous constructs with several items and complex relations, PLS-SEM was chosen. Henseler et al. [99] reported that because PLS-SEM is a non-parametric method, there is thus a need to use bootstrapping to assess the significance of path coefficients and to interpret the indirect effect of a construct. Bootstrapping is a resampling procedure used to assess the precision of the estimates [100].

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Measurement Model

Cronbach’s alpha () was used to verify internal consistency. As indicated in Table 2, values are in the range of 0.724 and 0.939, and hence are acceptable. Composite reliability≥ 0.70 and AVE are greater than 0.50, thus indicating that all scales had reasonable composite and convergent validity, as reported by Nunnally [101].

Table 2.

Reliability and validity.

For discriminant validity (DV) the square root of AVE was used, with the the correlation (r) of variables [102]. The diagonal values, as indicated in Table 3, are higher than ‘r’ of the constructs. The DV as per HTMT ratio is near the threshold, as is presented in Table 4. Thus, we moved ahead with further analysis.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Heterotrait/monotrait ratio.

As indicated in Table 5, the VIF values were all < 3, and hence depicted with no multicollinearity, suggesting that we could proceed with the structural model.

Table 5.

Inner and outer VIF.

We analyses the outer loadings to validate whether these values were significance. As seen in Table 6, all values were significant with p values ≤ 0.001.

Table 6.

Outer Loadings.

As the loadings for all the EB sub-constructs—EA, PBC and SN—were greater than 0.70 and significant (p ≤ 0.01), we can accept H1.

In terms of highly important ECs: RTS ← ECs; 0.905; followed by LS ← ECs: 0.904; PS ← ECs 0.901; OIS ← ECs 0.895; and SS ← ECs 0.876. Hence, H2 is empirically supported. As highlighted by Shane [103] when exploiting a discovery opportunity it is important for a leader to have specific knowledge and information associated with the opportunity.

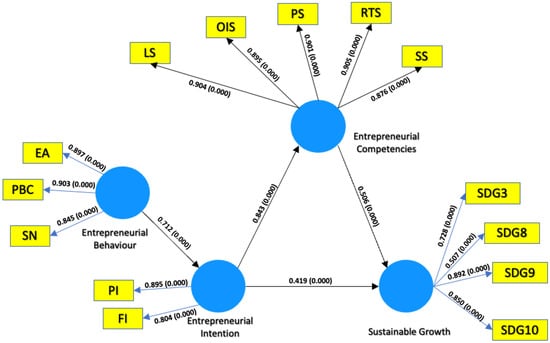

4.2. Structural Model: Path Analysis

PLS-SEM was applied to analyse the results. The outcomes are shown in Figure 2 and Table 7. The loading of EA←EPB is 0.897; for PBC←EPB it is 0.903; and for SN←EPB the value is 0.845. The value of EPB→EI is positive 0.506 with (T = 11.357 and p ≤ 0.001). Hence, EPB affirmatively influences EI. Accordingly, hypothesis H3 is empirically supported. The -value of EI→SG is 0.419 (T = 9.230; p ≤ 0.001). Thus, H4 is empirically supported. Though EI directly influence SG, we were interested in understanding whether ECs mediate EI and SG. The effect of EI through ECs was 0.843* > 0.546 = 0.426, which is more than the direct effect (0.419) and significant (t-values 56.358 and 11.357). Hence, we accept H5. Concerning the last hypothesis, EPB→EI→(ECs)→SG. As seen through the R-square and R-square adjusted values 0.789 and 0.788, respectively. Thus, the model highlights that EB influences EI and EI, mediated by ECs, impacts sustainable growth when measured through SDG3, SDG8, SDG9, and SDG10. Thus, H6 is empirically supported by results.

Figure 2.

Relationships between entrepreneurial behavior, entrepreneurial intentions (mediated by entrepreneurial competencies) with sustainable growth (through SDG 3, 8, 9, and 10).

Table 7.

Paths coefficients and model fit.

5. Discussion

The outcomes of this research highlight that EPB is a multidimensional construct encompassing entrepreneurial attitude, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms. All these sub-constructs are significant and hence critical. The high loadings of PBC indicate that it has greater relevance compared to EA and SN. Earlier researchers, Bosnjak et al. [10] and Ajzen [46], have considered PBC as a determinant of self-efficacy and the results of this study support a positive and significant relation between EPB and EI. This also corroborates reports by Shook et al. [65] and Souitaris et al. [104]. The outcomes of this research endorse that all EPB sub-constructs are important. The research outcomes of current paper reveal that the EPB of engineering students significantly support their EI. Former studies on the TPB model support that attitude affects EI [86,105].

The outcomes of the current study validate the role of competencies in encouraging SG, as endorsed by El-Gohary et al. [106]. Al-Mamary et al. [107] pointed out that competencies focused on mindset transformation significantly influence venture success through EI. ECs have an important role in entrepreneurial success. ECs (leadership skills (LS); risk-taking skills (RTS); and perseverance skills (PS)), considered as basic skills for entrepreneurship, have emerged as highly significant skills. The results of the current study indicate that basic competencies are important for realizing the goals of the enterprise and enhance its competitiveness. These skills have been endorsed prefiously by Schumpeter [59], Gundry et al. [60], Chatterjee and Das [66], and Wickham [62]. These were followed by enterprise-launching competencies, including opportunity identification skills (OIS). The next category of skills is related to enterprise management competencies, such sa societal skills (SS). Enterprise management competencies enable the entrepreneur to understand the market and lists their convictions to succeed. This study supports that requisite competencies help in enhancing the chances of success in entrepreneurship. The study by Banha et al. [9] suggested increasing the importance of entrepreneurial education programs focusing on entrepreneurial skills will train and prepare prospective entrepreneurs with an active and dynamic mindset and ensuring they can adjust and perform in society.

The outcomes of this study highlight that perceived entrepreneurial behaviour through EI (mediatde by ECs) enhances sustainable growth. The results bear testimony to SDG3, SDG8, SDG9, and SDG10, as a means to move towards sustainable growth. This is supported by earlier research [106,108]. Thus, EI mediated by ECs supports achieving sustaining growth when measured through SDG3, SDG8, SDG9, and SDG10. The study by Nabi et al. [109] highlighted the traditional skills and pedagogies and called for new or less-emphasised directions for future research. These include the impact of indicators related to the intention-to-behaviour transition. The current study provides a direction for developing countries, such as India, to develop the ECs of students to stimulate the success and sustained growth of enterprises.

6. Implications of the Study

The implications have been classified as theoretical and practical.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The theoretical contributions of this study help motivate engineering students to enhance their chances of becoming entrepreneurs and to stimulate the sustainability of entrepreneurial ventures. Growing uncertainties, e.g., recession, COVID-19, etc., have caused increasing unemployment ([110,111]), thus enhancing the relevancy of this study. It contributes to knowledge in terms of HEI’s role in promoting entrepreneurship amongst engineering graduates by focusing on competencies. There are many studies with diverse findings in developed nations; however, only a few have considered them from the perspective of a developing country, such as India. This study’s results are very important to HEIs, proving that HEIs need to focus on ECs to link EI and SG, highlighting specific SDGs.

6.2. Practical Implications

The findings support that EM has a significant positive influence on EI. Entrepreneurship needs to be promoted in HEIs by focusing on factors influencing EM and EI. Further, the study suggests that EIs may directly promote SG. The findings bring forth that ECs may mediate and enhance the effect of EI on SG. A holistic focus on ECs will certainly go a long way in manifesting EI to SG. The findings of this study offer crucial insights for sustainable ventures. Although there has been a plethora of research on entrepreneurial skills and competencies, as indicated by Brinckmann et al. [112], Knight et al. [113], and Arafeh [114], there is opportunity for theoretical and empirical analysis. The present study is an endeavour in this direction. To enhance the chances of success there is a need to trigger and focus behavioural competencies covering three critical entrepreneurial skills, (LS; PS and RTS). HEIs need to focus on these skills. However, this fails to account for the importance of other skills, such as enterprise-launching competencies (i.e., OIS); and enterprise-managing competencies, (i.e., SS). Going from EM to EI, including requisite ECs, we have made a sincere effort to propose and offer a valuable framework to reflect and enhance the chances of SG through SDG3, SDG8, SDG9, and SDG10. This framework will be the basis for investigating the essential motivations for entrepreneurship to help translate motivation to intention and improve the the training competencies linked to sustainable growth. In view of this, the study makes a genuine contribution towards the cohesive and assimilated knowledge of entrepreneurial motivation, intention, competencies and maintenance literature. Thus, to expedite EM–EI(ECs)–SG interaction, the state governments may take initiatives to ensure that ECs, through experiential training, enhance the development of new skills for the long-term survival of entrepreneurial ventures. EE needs to strengthen learning in HEIs to promote students to adopt entrepreneurship; however, as the results indicate, the focus must be on developing ECs. Banha et al. [115] provided evidence of how the NUTS III sub-regions could be a good vehicle for the diffusion and implementation of EE programmes in the European Union. This may be followed and adopted by other countries. Other researchers also reported EE programs able to develop the entrepreneurial capabilities of students and improve their success as entrepreneurs [116,117,118]. This study has re-emphasized the argument by Nabi and Linán [2] that individuals with the necessary entrepreneurial competencies will possess favourable entrepreneurial behaviours if surrounded by supportive people who value entrepreneurship.

7. Limitations of the Study and Future Work

This study has focussed on engineering graduates enrolled on entrepreneurship courses from top-rated institutions. The reason for taking engineering institutions was that they possessed business incubation facilities on their campus, thus could focus on providing entrepreneurial training. This helped in promoting entrepreneurial talent at these institutions. The research covers the added dimensions of earlier studies on EM and EI. The current study highlights the significance of ECs in SG through SDG3, SDG8, SDG9, and SDG10. In future, the study will be extended to management institutions and upgraded with feedback from BI managers regarding how these training programs can help to increase the spread and survival of start-ups. In future research, demographic variables can be used as control variables to validate the proposed model. The study can be extended to other developing countries, such as India. BI perspectives may be included to understand how training modules may be designed to enhance the ECs of prospective entrepreneurs.

Author Contributions

The work presented here was conducted by S.M. under the supervision of R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data for this study is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support provided by 12 Higher Engineering Institutions for the collection of data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted without any commercial or financial assistance. The authors also declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Scale for EPB, EI, ECs and SG.

Table A1.

Scale for EPB, EI, ECs and SG.

| Entrepreneurial Perceived Behaviour | Literature Support |

|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Attitude (towards self-employment) (Why do you want to an entrepreneur?) | |

| For financial security. | Hessels et al. [119] |

| To provide employment. | |

| To take advantage of my creative talent. | |

| To earn a reasonable living | |

| To exploit opportunities in the market. | |

| Subjective Norm (How will you use your entrepreneurship skills?) | |

| Entrepreneurial family culture. | Holcomb et al. [120] |

| To use skills learned in the university/institute. | |

| Follow the example of someone that I admired | |

| To invest personal savings | |

| To maintain my family | |

| I enjoy taking risk | |

| Perceived Behavioural Control (Why?) | |

| To be my own boss | Gerba [39], Okpara [92], Barringer and Ireland [121] |

| To realise my dream | |

| Increase my prestige and status. | |

| For my personal freedom | |

| To have an enjoyable life | |

| To challenge myself | |

| Good economic environment | |

| For my own satisfaction and growth | |

| Entrepreneurial Training (Requirements) | |

| Opportunity Identification Skills | |

| To enable them to think of products/services that could be offered in the market. | Chatterjee and Das [66], Loué and Baronet [68] |

| To help them know about the market needs for determined products/services. | |

| To help them possess ability to detect business opportunities in the market. | |

| To make them observe complaints about some products/services | |

| To enable them to think about new market opportunities. | |

| To help them imagine the possibility of success of products/services in the market. | |

| Perseverance Skills | |

| To assist them facing difficulties. | Tseng [122] |

| To enable to employ extra effort to overcome adversaries. | |

| To help them face difficult situations as personal challenges. | |

| To help them tackle the obstacles with ease. | |

| Societal skills | |

| To enable to communicate effectively with friends | Huber et al. [63], Rae [123] |

| To help them relate easily with other persons. | |

| To enable them to contact other persons. | |

| To help develop extroversion | |

| Risk Taking Skills | |

| To enable them to rethink financial bet in projects that can bring advantages in the future | Gürol and Atsan [124], Diochon et al. [125] |

| To help them manage financial risks for potential benefits. | |

| To expose them to risky situations. | |

| To help them to develop an attitude to bear risks. | |

| Leadership Skills | Loué and Baronet [68] |

| To enable them to influence other people’s opinions. | |

| To enable them to convince others. | |

| To assist them to inspire other persons to do what they want. | |

| To enable them to inspire others. | |

| To assist in making others follow them. | |

| Entrepreneurial Intention | |

| Immediate Intention | |

| I am ready to do anything to be an entrepreneur | |

| My professional goal is to become an entrepreneur | |

| I have very seriously thought of starting a firm | |

| I shall make every effort to start and run my own firm | |

| I have already prepared myself to become an entrepreneur | |

| I have the firm intention to start a firm after completing studies | |

| I want to be my own boss. | |

| Future Intention | |

| I am determined to create a firm in the future | |

| I have very seriously thought of starting a firm in future | |

| I have strong intention to start a business someday | |

| Sustainable Growth | |

| Entrepreneurial success is identified with: | Gorgievski et al. [78], Kiviluoto [79], Walker and Brown [80], Zhou et al. [81], Richard et al. [83] |

| SDG8: the financial yield of the company | |

| SDG9: good position in the market | |

| SDG8: firm’s growth | |

| SDG9: increase in the number of employees | |

| SDG8: sales growth | |

| SDG8: increase in productivity | |

| SDG10: stakeholder satisfaction | |

| SDG10: public recognition | |

| SDG3: good reputation | |

| SDG3: fulfilment of societal needs | |

References

- Gatti, L.; Ulrich, M.; Seele, P. Education for sustainable development through business simulation games: An exploratory study of sustainability gamification and its effects on students’ learning outcomes. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Liñán, F. Considering business start-up in recession time: The role of risk perception and economic context in shaping the entrepreneurial intent. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2013, 19, 633–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hueso, J.A.; Jaén, I.; Liñán, F. From personal values to entrepreneurial intention: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, 27, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lortie, J.; Castogiovanni, G. The theory of planned behavior in entrepreneurship research: What we know and future directions. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 935–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otache, I.; Umar, K.; Audu, Y.; Onalo, U. The effects of entrepreneurship education on students’ entrepreneurial intentions: A longitudinal approach. Educ. Train. 2021, 63, 967–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: The SDGs in Action. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals/reduced-inequalities (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Nowiński, W.; Haddoud, M.Y.; Lančarič, D.; Egerová, D.; Czeglédi, C. The impact of entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and gender on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in the Visegrad countries. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 44, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, M.; Kiran, R.; Bose, S.C. Understanding the relevance of experiential learning for entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A gender-wise perspective. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2023, 21, 100760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banha, F.; Coelho, L.S.; Flores, A. Entrepreneurship Education: A Systematic Literature Review and Identification of an Existing Gap in the Field. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, M.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. The theory of planned behavior: Selected recent advances and applications. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Sánchez, V.; Mitre-Aranda, M.; del Brío-González, J. The entrepreneurial intention of university students: An environmental perspective. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2022, 28, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Simeone, A.; Kautonen, T. Senior entrepreneurship following unemployment: A social identity theory perspective. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2021, 15, 1683–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. The design logic and development enlightenment of American social entrepreneurship curriculum. Entrep. Educ. 2021, 4, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogatyreva, K.; Edelman, L.F.; Manolova, T.S.; Osiyevskyy, O.; Shirokova, G. When do entrepreneurial intentions lead to actions? The role of national culture. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.P.; Le, A.N.H.; Xuan, L.P. A systematic literature review on social entrepreneurial intention. J. Soc. Entrep. 2020, 11, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jubari, I.; Hassan, A.; Liñán, F. Entrepreneurial intention among University students in Malaysia: Integrating self-determination theory and the theory of planned behavior. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 1323–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Zaman, U.; Waris, I.; Shafique, O. A serial-mediation model to link entrepreneurship education and green entrepreneurial behavior: Application of resource-based view and flow theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashari, H.; Abbas, I.; Abdul-talib, A.N.; Zamani, S.N.M. Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Development Goals: A Multigroup Analysis of the Moderating Effects of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurial Intention. Sustainability 2022, 14, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cera, G.; Mlouk, A.; Cera, E.; Shumeli, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention. A quasi-experimental research design. J. Compet. 2020, 12, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldureanu, G.; Ionescu, A.M.; Bercu, A.M.; Bedrule-Grigoruţă, M.V.; Boldureanu, D. Entrepreneurship Education through Successful Entrepreneurial Models in Higher Education Institutions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasianchavari, A.; Moritz, A. The impact of role models on entrepreneurial intentions and behavior: A review of the literature. Manag. Rev. Q. 2021, 71, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T.J.; Qian, S.; Miao, C.; Fiet, J.O. The Relationship Between Entrepreneurship Education and Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Meta-Analytic Review. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 217–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Chandran, V.; Klobas, J.E.; Liñán, F.; Kokkalis, P. Entrepreneurship education programmes: How learning, inspiration and resources affect intentions for new venture creation in a developing economy. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 18, 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almahry, F.F.; Sarea, A.M.; Hamdan, A.M. A review paper on entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurs’ skills. J. Entrep. Educ. 2018, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Government Initiatives. Available online: https://www.startupindia.gov.in/content/sih/en/international/go-to-market-guide/government-initiatives.html (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Pooja, M. These 8 Government Schemes Are Making the Indian Startup Ecosystem Robust. Available online: https://yourstory.com/2022/05/government-schemes-indian-startup-ecosystem-samridh-msmes (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- List Of Government Schemes for Startups in India. Available online: https://startuptalky.com/list-of-government-initiatives-for-startups/ (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Atal Innovation Mission (AIM). Available online: https://aim.gov.in/ (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Su, X.; Liu, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L. To be happy: A case study of entrepreneurial motivation and entrepreneurial process from the perspective of positive psychology. Sustainability 2020, 12, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, Z.; Gubik, A.S.; Bereczk, A. The social dimension of the entrepreneurial motivation in the central and eastern european countries. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2019, 7, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmert, M.; Cross, A.R.; Cheng, Y.; Kim, J.J.; Kohlbacher, F.; Kotosaka, M.; Waldenberger, F.; Zheng, L.J. The distinctiveness and diversity of entrepreneurial ecosystems in China, Japan, and South Korea: An exploratory analysis. Asian Bus. Manag. 2019, 18, 211–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, J.; Rietveld, C.A.; van der Zwan, P. Self-employment and work-related stress: The mediating role of job control and job demand. J. Bus. Ventur. 2017, 32, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampene, A.K.; Li, C.; Khan, A.; Agyeman, F.O.; Opoku, R.K. Yes! I want to be an entrepreneur: A study on university students’ entrepreneurship intentions through the theory of planned behavior. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, K.P.; DiBello, A.M.; Peterson, K.P.; Neighbors, C. Theory-driven interventions: How social cognition can help. In The Handbook of Alcohol Use; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 485–510. [Google Scholar]

- Engle, R.L.; Dimitriadi, N.; Gavidia, J.V.; Schlaegel, C.; Delanoe, S.; Alvarado, I.; He, X.; Buame, S.; Wolff, B. Entrepreneurial intent: A twelve-country evaluation of Ajzen’s model of planned behavior. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2010, 16, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Ethnic entrepreneurship: Studying Chinese and Indian students in the United States. J. Dev. Entrep. 2007, 12, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammari, M.; Waleed, R. Entrepreneurial intentions of private university students in the kingdom of Bahrain. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2018, 10, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.; Santos, T.; Sousa, M.; Oliveira, J.C.; Oliveira, M.; Lopes, J.M. Entrepreneurial intention among women: A case study in the Portuguese academy. Strateg. Chang. 2022, 31, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerba, D.T. Impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions of business and engineering students in Ethiopia. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2012, 3, 258–277. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, G.; Song, Y.; Pan, B. How university entrepreneurship support affects college students’ entrepreneurial intentions: An empirical analysis from China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, S.; Raghunathan, R.; Rao, N.M. The antecedents of entrepreneurial intention among women entrepreneurs in India. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2020, 14, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F., Jr.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez, M.; Serrano-Bedia, A.M.; García-Piqueres, G. An analysis of factors affecting students perceptions of learning outcomes with Moodle. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2020, 44, 1114–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, L. Entrepreneurship education and sustainable development goals: A literature review and a closer look at fragile states and technology-enabled approaches. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanoë-Gueguen, S.; Liñán, F. A longitudinal analysis of the influence of career motivations on entrepreneurial intention and action. Can. J. Adm. Sci. Can. Sci. L’Administration 2019, 36, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim-Soon, N.; Ahmad, A.R.; Ibrahim, N.N. Entrepreneurial motivation and entrepreneurship career intention: Case at a Malaysian Public University. Crafting Glob. Compet. Econ. 2014, 2020, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Ariff, A.H.M.; Bidin, Z.; Sharif, Z.; Ahmad, A. Predicting entrepreneurship intention among Malay university accounting students in Malaysia. UNITAR e-J. 2010, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Iffan, M. Impact of Entrepreneurial Motivation on Entrepreneurship Intention. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Economic, Social Science and Humanities (ICOBEST 2018), Bandung, Indonesia, 22 November 2018; pp. 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinc, M.S.; Budic, S. The Impact of Personal Attitude, Subjective Norm, and Perceived Behavioural Control on Entrepreneurial Intentions of Women. Eurasian J. Bus. Econ. 2016, 9, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambad, S.N.A.; Damit, D.H.D.A. Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intention Among Undergraduate Students in Malaysia. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 37, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlutürk, M.; Mardikyan, S. Analysing factors affecting the individual entrepreneurial orientation of university students. J. Entrep. Educ. 2018, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Otchengco, A.M., Jr.; Akiate, Y.W.D. Entrepreneurial intentions on perceived behavioral control and personal attitude: Moderated by structural support. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2021, 15, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, K.; Hannon, P.; Cox, J.; Ternouth, P.; Crowley, T. Developing Entrepreneurial Graduates: Putting Entrepreneurship at the Centre of Higher Education; NESTA London: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Seun, A.O.; Kalsom, A.W. New venture creation determinant factors of social Muslimpreneurs. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2015, 23, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cheraghi, M.; Schøtt, T. Education and training benefiting a career as entrepreneur: Gender gaps and gendered competencies and benefits. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2015, 7, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbagh, N.; Menascé, D.A. Student perceptions of engineering entrepreneurship: An exploratory study. J. Eng. Educ. 2006, 95, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstrom, T.R.; Talmage, C.A. Entrepreneurial skills for sustainable small business: An exploratory study of SCORE, with comparison. Community Dev. 2018, 49, 450–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Theorie der Wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung: Eine Untersuchung über Unternehmergewinn, Kapital, Kredit, Zins und den Konjunkturzyklus; Duncker und Humblot: Berlin, Germany, 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Gundry, L.K.; Ofstein, L.F.; Kickul, J.R. Seeing around corners: How creativity skills in entrepreneurship education influence innovation in business. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2014, 12, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Miller (1983) revisited: A reflection on EO research and some suggestions for the future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 873–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, P.A. Strategic Entrepreneurship; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, L.R.; Sloof, R.; Praag, M.V. The effect of early entrepreneurship education: Evidence from a field experiment. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2014, 72, 76–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglio, C.M.; Katz, J.A. The psychological basis of opportunity identification: Entrepreneurial alertness. Small Bus. Econ. 2001, 16, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shook, C.L.; Priem, R.L.; McGee, J.E. Venture creation and the enterprising individual: A review and synthesis. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 379–399. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, N.; Das, N. A study on the impact of key entrepreneurial skills on business success of Indian micro-entrepreneurs: A case of Jharkhand region. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2016, 17, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römer-Paakkanen, T.; Pekkala, A. Generating entrepreneurship from students’ hobbies. In Proceedings of the Promoting Entrepreneurship by Universities, the 2nd International FINPIN Conference, Hämeenlinna, Finland, 20 April 2008; Volume 20, p. 340. [Google Scholar]

- Loué, C.; Baronet, J. Toward a new entrepreneurial skills and competencies framework: A qualitative and quantitative study. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2012, 17, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, L.W. The goals and impact of educational interventions in the early stages of entrepreneur career development. In Proceedings of the Internationalising Entrepreneurship Education and Training Conference, Arnhem, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 24–26 June 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, J.; Stanworth, J. Education and training for enterprise: Some problems of classification, policy, evaluation and research. Int. Small Bus. J. 1989, 7, 83–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, D. Six steps to heaven: Evaluating the impact of public policies to support small businesses in developed economies. In The Blackwell Handbook of Entrepreneurship; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 176–193. [Google Scholar]

- Kolvereid, L.; Moen, Ø. Entrepreneurship among business graduates: Does a major in entrepreneurship make a difference? J. Eur. Ind. Train. 1997, 21, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, C.; Izedonmi, P.F. The effect of entrepreneurship education on students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2010, 10, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Liñán, F.; Rodriguez-Cohard, J.C.; Rueda-Cantuche, J.M. Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels: A role for education. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2011, 7, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresch, D.; Harms, R.; Kailer, N.; Wimmer-Wurm, B. The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial intention of students in science and engineering versus business studies university programs. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 104, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirokova, G.; Osiyevskyy, O.; Bogatyreva, K. Exploring the intention–behavior link in student entrepreneurship: Moderating effects of individual and environmental characteristics. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Huang, T.; Xiao, Y. Assessing the impact of entrepreneurial education activity on entrepreneurial intention and behavior: Role of behavioral entrepreneurial mindset. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 26292–26307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgievski, M.J.; Moriano, J.A.; Bakker, A.B. Relating work engagement and workaholism to entrepreneurial performance. J. Manag. Psychol. 2014, 29, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiviluoto, N. Growth as evidence of firm success: Myth or reality? Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2013, 25, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.; Brown, A. What success factors are important to small business owners? Int. Small Bus. J. 2004, 22, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wu, W.P.; Luo, X. Internationalization and the performance of born-global SMEs: The mediating role of social networks. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2007, 38, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtenhagen, L.; Naldi, L.; Melin, L. “Business growth”—Do practitioners and scholars really talk about the same thing? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 289–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, P.J.; Devinney, T.M.; Yip, G.S.; Johnson, G. Measuring Organizational Performance: Towards Methodological Best Practice. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 718–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandstätter, H. Personality aspects of entrepreneurship: A look at five meta-analyses. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andruszkiewicz, K.; Nieżurawski, L.; Śmiatacz, K. Role i satysfakcja interesariuszy przedsiębiorstw w sytuacji kryzysowej. Mark. Rynek 2014, 8, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Obschonka, M.; Silbereisen, R.K. Person–city personality fit and entrepreneurial success: An explorative study in China. Int. J. Psychol. 2019, 54, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holienka, M.; Pilková, A.; Jancovicová, Z. Youth entrepreneurship in Visegrad countries. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2016, 4, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, M.; Mueller, P. The persistence of regional new business formation-activity over time—Assessing the potential of policy promotion programs. J. Evol. Econ. 2007, 17, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, O.; Roman, A.; Rusu, V.D. The Nexus between Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth: A Comparative Analysis on Groups of Countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, J.; McCarthy, N.; O’Connor, M. The role of entrepreneurship in stimulating economic growth in developed and developing countries. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2018, 6, 1442093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickul, J.; Gundry, L.K.; Barbosa, S.D.; Whitcanack, L. Intuition versus analysis? Testing differential models of cognitive style on entrepreneurial self–efficacy and the new venture creation process. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpara, F.O. The value of creativity and innovation in entrepreneurship. J. Asia Entrep. Sustain. 2007, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y.W. Development and cross–cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G. A general method for estimating a linear structural equation system. ETS Res. Bull. Ser. 1970, 1970, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos-Aparicio, G. Partial least squares (PLS) methods: Origins, evolution, and application to social sciences. Commun.-Stat.-Theory Methods 2011, 40, 2305–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E.E. Choosing PLS path modeling as analytical method in European management research: A realist perspective. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petter, S. “Haters Gonna hate”: PLS and information systems research. ACM SIGMIS Database Database Adv. Inf. Syst. 2018, 49, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; SAGE Publications: Thausand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric theory—25 years ago and now. Educ. Res. 1975, 4, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S. Prior knowledge and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Organ. Sci. 2000, 11, 448–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souitaris, V.; Zerbinati, S.; Al-Laham, A. Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of learning, inspiration and resources. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 566–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaegel, C.; Koenig, M. Determinants of entrepreneurial intent: A meta–analytic test and integration of competing models. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 291–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gohary, H.; Sultan, F.; Alam, S.; Abbas, M.; Muhammad, S. Shaping Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intentions among Business Graduates in Developing Countries through Social Media Adoption: A Moderating-Mediated Mechanism in Pakistan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamary, Y.H.S.; Abdulrab, M.; Alwaheeb, M.A.; Alshammari, N.G.M. Factors impacting entrepreneurial intentions among university students in Saudi Arabia: Testing an integrated model of TPB and EO. Educ. Train. 2020, 62, 779–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorio, A.M.; Puumalainen, K.; Fellnhofer, K. Drivers of entrepreneurial intentions in sustainable entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A.; Krueger, N.; Walmsley, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2017, 16, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Villaverde, J.; Guerrón-Quintana, P.A. Uncertainty shocks and business cycle research. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 2020, 37, S118–S146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.R.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J.; Kost, K.J.; Sammon, M.C.; Viratyosin, T. The Unprecedented Stock Market Impact of COVID-19; Technical Report; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brinckmann, J.; Grichnik, D.; Kapsa, D. Should entrepreneurs plan or just storm the castle? A meta-analysis on contextual factors impacting the business planning–performance relationship in small firms. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.P.; Greer, L.L.; De Jong, B. Start-up teams: A multidimensional conceptualization, integrative review of past research, and future research agenda. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2020, 14, 231–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafeh, L. An entrepreneurial key competencies’ model. J. Innov. Entrep. 2016, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banha, F.; Flores, A.; Coelho, L.S. NUTS III as Decision-Making Vehicles for Diffusion and Implementation of Education for Entrepreneurship Programmes in the European Union: Some Lessons from the Portuguese Case. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akmaliah, Z.; Pihie, L.; Bagheri, A. An Exploratory Study of Entrepreneurial Attributes Among Malaysian University Students. Life Sci. J. 2012, 9, 1097–8135. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M.Y.; Chan, W.S.; Mahmood, A. The effectiveness of entrepreneurship education in Malaysia. Educ. Train. 2009, 51, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, M.; Aziz, A.R.A. Entrepreneurship education in developing country: Exploration on its necessity in the construction programme. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2008, 6, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, J.; Rietveld, C.A.; van der Zwan, P. Unraveling two myths about entrepreneurs. Econ. Lett. 2014, 122, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, T.R.; Ireland, R.D.; Holmes, R.M., Jr.; Hitt, M.A. Architecture of entrepreneurial learning: Exploring the link among heuristics, knowledge, and action. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barringer, B.R.; Ireland, R.D. Successfully Launching New Ventures; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, C.C. Connecting self-directed learning with entrepreneurial learning to entrepreneurial performance. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2013, 19, 425–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, D. Connecting enterprise and graduate employability: Challenges to the higher education culture and curriculum? Educ. Train. 2007, 49, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürol, Y.; Atsan, N. Entrepreneurial characteristics amongst university students: Some insights for entrepreneurship education and training in Turkey. Educ. Train. 2006, 48, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diochon, M.; Menzies, T.V.; Gasse, Y. Exploring the nature and impact of gestation-specific human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. J. Dev. Entrep. 2008, 13, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).