Abstract

Sustainable development is a widely discussed topic. English language education plays the dominant role in China, but the education of languages other than English (LOTEs) is more important for sustainable development. Based on a case study of German language education, this paper draws SWOT analysis to discuss the current foreign language education in China associated with sustainable development. We find that there are four current trends in the sustainable development of foreign language education in China: promotion of sustainable multilingual education, cultivation of sustainable citizens, integration of cultural values for sustainable development and digitalization for sustainable foreign language education. There are also challenges and new perspectives. A rational and systematic policy of multilingualism should be planned. In order to cultivate sustainable citizens who are able to respond to various global problems, the curricula, teaching materials and examinations for LOTE teaching at secondary schools and universities should be co-designed to work with each other. In order to integrate cultural values effectively, more suitable teaching materials should be developed and published, and teachers need to be trained for practicing these contents in class. Digitization in teaching, research and learning should be promoted.

1. Introduction

Sustainability is a complex and wildly discussed topic in many fields including the field of foreign language education. Sustainable development (based on the 17 goals of UNESCO 2017) encompasses future-oriented, whole-society and global dimensions of ecological sustainability, social and generational justice, democratic citizenship, economic performance and well-being of the world’s population at large. “[To] foster the right types of values and skills that will lead to sustainable and inclusive growth, and peaceful living together” [1] (p. 7), education has been playing a key role. As sustainability is not a local issue, all sustainability related problems ought to be discussed on the macro scale, which requires an internationally shared means of communication such as a language [2]. Therefore, it is pointed out that foreign language education is crucial to the achievement of all the 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) of UNESCO. In this context, foreign language education should be adapted to sustainable development.

One big problem facing the sustainable development of foreign language education in most countries in the world including China is that with the rise of English as an international language, it has been the dominant language in many contexts, while languages other than English (LOTEs) are in decline. Many countries have recognized that English is identified as the most important medium of global language, but not the only one [3]. As in other countries, China is aware of this situation and has adjusted its foreign language education policies in recent years, particularly in relation to LOTEs, in order to promote the sustainable development of the overall foreign language education in China. The number of German learners in China has exceeded 145,000 by the end of 2020 [4], and is one of the most important LOTEs. In this study, based on a case study of German language education in China, we discuss the current foreign language education in China associated with the sustainable development. To this end, this study focuses on two questions:

- (1)

- What are the current trends in the sustainable development of foreign language education in China?

- (2)

- What are the challenges and perspectives facing the sustainable development of foreign language education in China?

2. Overview of Foreign Language Education in China

Since 1949, the Chinese foreign language education has gone through five periods: the period of establishment (1949–1965), the period of stagnation (1966–1976), the period of development (1977–1999), the period of acceleration (1999–2017), and a new period (2013–present) [5].

From 1949 to 1964, because of the close relations between China and Russia, Russian was almost the only foreign language in China and should be taught in all schools. In the ten years of Cultural Revolution between 1966 and 1977, Chinese foreign language education stagnated. After this period, with the worsening of the relations between China and Russia and the thawing of the relations between China and the USA, English began to become the main foreign language in China. To meet the demands of communication with western countries, China’s government encouraged people to learn English, requiring all public schools to set up English courses for all students. In particular, English is treated as one of required three courses (the other two are Chinese and mathematics) for all primary, middle and high school students. After learning English in primary, middle and high schools of 12 years, the high school students choose English as the foreign language subject for College Entrance Examination (also called Gaokao). From 1999, universities began to expand in China, and many universities added foreign language majors. By the end of 2007, there had been 899 universities nationwide offering English majors [6]. In the new era since 2013, the “English fever” has begun to cool down, and the LOTEs are given opportunities to develop. The initiative of “Belt and Road” proposed in 2013 triggered especially China’s renewed investment in developing programs of LOTEs in different educational contexts, although since the 1980s, China has determined to develop English language education with due attention to other languages such as Japanese and Russian [7] and high school students have been able to choose Japanese or Russian for Gaokao. The number of students choosing LOTEs for Gaokao is extremely small compared to English. Along with the introduction of the new national curriculum program and standards for high school education in 2018, German, French and Spanish are also officially recognized as the foreign language subjects in Gaokao [8]. In higher education, the English major is the largest and most populous among the foreign language programs. And the number of learners of non-English majors who learn English as a foreign language in universities is even larger. More than 22.85 million candidates took the “Examination of Higher Education English Level 4” and “Examination of Higher Education English Level 6” (Only students in higher education institutions are eligible to register for the two exams and this exam is taken twice a year, in June and December) in 2021 [9] (p. 11). Since 2018, a few universities in China are beginning to encourage students to learn a LOTE as a second and even third foreign language [10].

However, English is the most important foreign language in Chinese language education [11], and the scale of LOTEs in different levels is relatively small in terms of the number of schools offering these foreign language courses, the number of learners and the impact. In an ever-changing world, the Chinese foreign language education has experienced new changes in the last five years. This study therefore focuses on the latest changes in the last five years.

3. Analysis Framework

In this study, we draw SWOT analysis to explore the opportunities and challenges for the sustainable development for foreign language education in China. SWOT analysis is an important strategic planning tool used by businesses and other organizations, and is used to ensure that there is a clear objective defined for the project or venture and that all factors related to the efforts, both positive and negative, are identified and addressed [12].

The Table 1 lists the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats that influence the sustainable development of education of foreign languages, especially of LOTEs, in China.

Table 1.

Influencing factors of foreign language education in China.

- Strengths

S1: Multilingual education in China has its intrinsic motivations as the development of economy, science and technology, close connection between China and the whole world, and increased international exchanges require a sustainable development of foreign language education, so as to enable individuals to develop sustainably for the new era and to empower a nation to participate in international affairs.

S2: After decades’ development of foreign language education in China, the concept of language education needs to be changed to cultivation of sustainable citizens.

- Opportunities

O1: The deepening of globalization and China’s globalization initiatives such as the “Belt and Road” initiative have created new framework conditions for the further development of foreign language education.

O2: In recent years, the concept of global sustainable development has developed and become widely accepted worldwide.

O3: Modern technological innovations have made the digitalization of foreign language education possible.

- Weaknesses

W1: A systematic policy on multilingualism is currently lacking.

W2: There is a lack of continuity in secondary education and university education in LOTEs. This is reflected in the lack of continuity in curriculums, accompanying teaching materials and lack of appropriate training for teachers.

W3: The integration of cultural values of foreign languages, especially of LOTEs, into teaching materials and process is not sufficient. Suitable teaching materials have not yet been published and teachers need to be trained.

- Threats

T1: English is a global language, and learners of LOTEs are few in number and have little influence.

T2: Technological advances and digital trends place high demands for both students and teachers.

4. Current Trends in the Sustainable Development of Foreign Language Education in China

Based on the above SWOT analysis, four current trends in the sustainable development of foreign language education in China are found out.

4.1. Promotion of Sustainable Multilingual Education

For a long time, English plays the dominant role in many countries in different educational contexts, while LOTEs are discriminated against and are in decline. In recent years, many countries have begun to recognize this status quo, because the languages of the world have to be protected in order to protect the cultures of the world and language is culture expressed in words [3] (p. 158). In order to achieve one of the SDGs that all learners can appreciate cultural diversity and the contribution of each culture to sustainable development [13], countries have raised the importance of multilingual education to solve the problem. In the USA, the National Foreign Language Center claims “to improve the capacity of the U.S. to communicate in languages other than English” (https://www.idealist.org/en/nonprofit/1bbf34d86f184eaa9ebe5e0494f4e4cb-national-foreign-language-center-riverdale (accessed on 22 March 2023)). In South Korea, the “Act on the Promotion of Special Foreign Language Education” and its supporting laws promulgated in 2016/17 are also important milestones in the development of less commonly taught language education [14].

In addition to the impact of international foreign language educational trend, the new emerging social, political and economic needs, especially the beginning of “Belt and Road” initiative in 2013, China has tried to develop LOTEs. In 2016, the Ministry of Education (MOE) issued the plan of “Developing Educational Cooperation along the Belt and Road”, stressing the need to expand multilingual education in China’s secondary- and tertiary-level institutions. In 2017, the MOE approved more than 20 foreign language degree programs including Hebrew, Persian and Serbian in more than 30 Chinese higher education institutions and encouraged secondary-school graduates to be recommenced for admission to LOTE major studies through favoring policies, such as early admission schemes or lower passing scores in the Gaokao [15]. Most importantly, German, French and Spanish in addition to English, Russian and Japanese were approved as an examination subject in the College Entrance Examination and new educational standards for these foreign languages were developed [8]. This means that five LOTEs as foreign language subjects are available in secondary-level education and the learners also have the chance to learn a second and a third foreign language. Meanwhile, the teaching of second and third foreign languages, including German and French, will be increasingly promoted, and was stipulated at the conference on the reform of foreign language education for non-major foreign language philology programs in 2018 [10] (p. 9). It is thus clear that foreign language education in China is being reformed with the aim of promoting lingual and cultural diversity and thus its sustainable development.

As a result of these policies, the number and scale of LOTE degree programs at Chinese universities have been growing dramatically, especially at Beijing Foreign Studies University, which has the longest history of LOTE education in China and offers most foreign language courses. By the end of 2020, the university has increased more than 100 language degree programs (https://www.bfsu.edu.cn/overview (accessed on 22 March 2023)). There has been a huzdramatic increase in the number of schools and universities offering these language courses, and LOTE learners have begun to increase greatly. We take German as an example. By the end of 2019, there had been around 23,400 Chinese students learning German in primary, middle, high schools. Along with the introduction of the new national curriculum program and standards for high school education in 2018, a considerable increase in the number of German learners in middle and high schools can be expected in the next few years. At the same time, the subject of German/German Studies continues to develop. After a moderate growth in the second half of the 20th century, the number of German Studies departments in Chinese universities has risen to 117 by 2017 [16] (p. 40), with Master’s programs at 33 universities and doctorates at 11 universities. More and more students are learning German as a second foreign language, which can be confirmed by the fact that in 2021, around 7000 Chinese students from more than 297 higher education institutions took the “Examination of Higher Education German Level 4” and the “Examination of Higher Education German Level 6” [17] (p. 50) (Only students in higher education institutions are eligible to register for the two exams). In fact, even more students are learning German as a second or third foreign language. Although the number of learners of German is incomparable to that of learners of English—for example, the number of people taking “Examination of Higher Education English Level 4” and “Examination of Higher Education English Level 6” exceeded 20 million in 2021 [9] (p. 11)—it should be seen that the German language as a LOTE has developed positively in recent years.

To sum up, benefiting from its sustainable multilingual education in recent years, China not only makes the most significant contribution to sustaining English as a global language [18], but also plays a role in promoting the learning and teaching of LOTEs as well.

4.2. Cultivation of Sustainable Citizens

In the new era, we need to educate the “sustainability citizens” who are able to collaborate, speak up and act for positive changes [19]. There is a general agreement that sustainability citizens need to have certain key competencies that allow them to engage constructively and responsibly with today’s world [20] (p. 10). The key competencies, such as system thinking competency, strategic competency, collaboration competency and critical thinking competency, are generally seen to be crucial to advance sustainable development of individuals [20,21]. In recent years, the foreign language education in China focuses on developing students’ key competencies so as to cultivate the sustainable citizens.

Key competencies have been a topic of interest in the international education landscape for a long time. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) first created and highlighted the idea of key-competencies by enriching its connotations and disseminated it globally soon after. According to the OEDC, a competency is defined as “more than just knowledge and skill”, but “the ability to meet complex demands by drawing on and mobilizing psychosocial resources (including skills and attitudes) in a particular context” [22] (p. 4). Following the OECD, the EU and the UNESCO accepted this term and worked on the concept continuously. China has also got involved in this trend. The key competencies for foreign language learning and teaching are localized, and a new term “Hexin-suyang” is introduced with the announcement of the new national curriculum program and standards for high school education in 2018. Along with this reform, German, French and Spanish were accepted in the Gaokao, and this concept is well adapted to these foreign languages.

The term Hexin-suyang is defined as “the key competencies, characters, and values that individuals show when they apply knowledge and skills to deal with complex situations” [23]. Many “local competences” are added to the Chinese framework of competences, such as Chinese morals and traditional culture competences, based on the assumption that they all constitute the central ideal of what it means to be the all-round developed person [24]. This means that foreign language education in today’s China is no longer merely competence-oriented, but goes beyond by placing greater emphasis on the development of sustainable citizens.

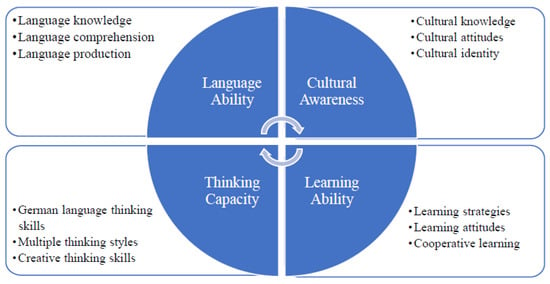

More importantly, to answer the question of how to achieve the overarching goals in education, subject key competencies are developed. Subject key competencies, by definition, are positive values, crucial characters, and key skills that learners acquire in learning each subject. Specifically for the six foreign language subjects, four subject key competencies, or four Hexin-suyang were set out: language ability, learning ability, thinking quality and cultural awareness. Under each subject key competence, there are still specific goals for teaching the foreign language. The Figure 1 shows four key competencies for German language.

Figure 1.

Four subject key competencies for German language.

Language ability, which is a basic and necessary ability for learners to learn, refers to the ability to understand and express meaning in a social context by way of listening, speaking, reading, viewing, and writing a foreign language, and also includes language awareness and a feel for language developed in the course of learning and using the language [23].

Learning ability refers to the ability to learn how to learn. Learning ability is not limited to learning methods and strategies, but also includes the knowledge and attitudes towards foreign language learning [25]. Mastery of learning ability has a great influence on learners’ enthusiasm for learning any foreign language and also for their lifelong learning of foreign languages.

Thinking quality is the brain’s indirect generalization of objective things and connections. It is based on perception and the procession of perceptual information through intellectual activities such as analysis and synthesis, abstraction, and generalization, and involves using the knowledge stored in memory as a medium to explore the internal essential connections and regularities of things [23].

Cultural awareness includes Chinese and foreign cultural knowledge, which is the basis for students to understand cultural connotations, to compare cultural similarities and differences, to absorb cultural essence, and to strengthen cultural self-confidence in language learning activities [23].

The four subject key competencies show that learning a foreign language includes not only learning and mastering of language knowledge and skills, but also the cultivation and improvement of learning ability, thinking quality, and cultural awareness [26]. Cultivating these abilities and qualities can truly contribute to the development of sustainable citizens and their lifelong learning, regardless of the foreign language being studied.

The development of sustainable citizens is recognized at both high schools and universities, and this particularly has had a positive impact on the LOTEs. The first quality standard for the university subject German Studies was published in 2018 and the instructions for university German have been developed [27], both of which follow this concept. For example, in the quality standard for the university subject German Studies, it is set out that the training objective of the German Studies degree is not only to impart and improve language skills, but also to train the German Studies students in the complex of practical skills, creativity, personal activity, intercultural skills, sense of responsibility and psycho-physical resilience in the situational context [28].

To sum up, the development of sustainable citizens as a talent development goal has been put into practice in the last five years and has greatly influenced the foreign language education in China, especially the LOTE education.

4.3. Integration of Cultural Values for Sustainable Development

For a long time, foreign language education in China had a wrong orientation that learning a foreign language requires students to spend too much time on rote-learning to pass examinations. Therefore, students focus more on language knowledge and skills, but ignore the culture embedded in language. Actually, language learning and teaching is not just about developing the language ability of individuals, and it also works toward an ideal of intercultural communication, a vision for life in a plurilingual world [29], which is consistent with one of SDGs that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development by 2030 [13]. In recent years, the foreign language education in China has been moving in this direction, integrating culture values into all aspects of foreign language education.

Culture along with learning a language involves different aspects, such as products, practices, persons, and perspectives [30] (p. 25). It was realized that it is through immersion into a foreign culture that the most important differences with one’s own culture come to the fore, and that the most important differences are in cultural values [31]. The cultural values that are currently having a very profound impact on Chinese society are the concept of “socialist core values” and the concept of “the community of shared future for mankind (CSFM)”. Socialist core values were originally proposed in 2012, and consist of 16 aspects (patriotism, dedication, integrity, friendship, freedom, equality, justice, rule of law, prosperity, democracy, and civilization, harmony), covering three different levels: individual, social and national levels. The CSFM concept was firstly introduced in 2013 and proposes a world community where the economic relations among nations should be based on the principle of win-win cooperation, which guarantees shared, just, and equitable development and prosperity for all [32]. Based on the concept of “socialist core values”, the CSFM concept extends its scope from individual to international relations. That is to say, the two concepts represent precisely the dominant cultural values of current Chinese society at four levels: personal, social, national and international levels. The two concepts are the values that China has put forward in the face of domestic and foreign changes and are a continuation of China’s excellent traditional culture in modern society. For example, the CSFM concept is a modern expression of the traditional Chinese values such as “World harmony” (天下大同) and “knowledge and action are one” (知行合一) [33].

More importantly, the two dominant concepts of cultural values in China are consistent with the global sustainable development pursued by the international community in the last two decades. The fundamental principles of sustainable development are augmented by political, legal and cultural dimensions: “Peace, security, stability and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the right to development, as well as respect for cultural diversity, are essential for achieving sustainable development and ensuring that sustainable development benefits all” [34] (p. 15). Resolutions on sustainability often refer to different levels. For example, in the final report of Johannesburg 2002, “we assume a collective responsibility to advance and strengthen the interdependent and mutually reinforcing pillars of sustainable development—economic development, social development and environmental protection—at the local, national, regional and global levels” [34].

Education is a right that transforms lives when it is accessible to all, relevant and underpinned by core shared values [20] (p. 1). It is when cultural values are similar that people are more likely to understand, appreciate and communicate with each other. The Chinese share quite a few values mainly from the concept of “socialist core values” and the concept CSFM with the international community. It is on this basis that China can interact with the international community in a friendly manner. Over the past five years, Chinese education, especially foreign language education, has sought to integrate these internationally shared cultural values, so that Chinese students can better understand students from other countries and communicate with them. With the introduction of the new national curriculum program and standards for high school education in 2018, learners are expected to compare, appreciate, criticize, and reflect on different cultures, while understanding, feeling, and experiencing excellent Chinese culture and foreign cultures [18]. Through the study of a foreign language, they can broaden their international horizons and improve ability of cultural appreciation and tolerance, enhance their understanding of excellent Chinese culture, and take the initiative to introduce Chinese culture to the whole world. In this way, Chinese learners can be prepared as global citizens to face global problems together with their partners around the world and promote global sustainable development together.

4.4. Digitalization for Sustainable Foreign Language Education

A large-scale survey on curriculum and instruction in China showed that rural middle school students have worse performance that urban ones in almost every schooling index, including school curriculum leadership, curriculum planning, teacher engagement, student learning quality, opportunities for learning, social relationships, family support und intervention, and learning outcomes [35]. These differences exist not only among different schools in rural or urban areas, but also among different classes within the same school. This situation of unfair development is even more pronounced in the case of education in LOTEs in China. Let’s take German language education as an example. On the one hand, the number of learners and schools at different levels offering German language courses has grown. On the other hand, German as a first, second or even third foreign language is studied in many secondary schools located in not only economically developed regions such as Beijing, Shanghai, etc., but also smaller cities in the economically relatively underdeveloped inland regions in Northeast and West China, where not a single German department is established at the universities [36]. Thanks to the use of information and communication technologies in the form of digital teaching, digital teacher training and digital seminars, China has provided quality education for different types of learners and eliminated educational inequalities, which is in line with one of the SDGs that quality education should ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all, in order to improve peoples’ lives and sustainable development [13], and promote sustainable foreign language education, especially sustainable LOTE education.

In recent years, almost all courses such as lectures, tutorials and seminars have taken place in digital teaching forms either synchronously or asynchronously, especially since the outbreak of COVID-19. Most of them were realized synchronously, and mainly in a traditional way, as action-oriented learning activities are difficult to manage without face-to-face communication and learners are not continuously motivated. Consequently, the learning effect is limited in synchronous teaching. However, through Massive Open Online Course (MOOC), teachers and learners are detached from time and place. The number of English-language MOOCs has grown rapidly because of its great impact and learners’ number, while the MOOCs of LOTEs have developed slowly. At the end of 2021, there were only 18 MOOCs in German Studies, an extremely low number, especially compared to the thousand MOOCs in English. Nevertheless, the 18 MOOCs include courses for language knowledge transfer as well as specialized courses such as linguistics, literature, regional studies, and history [17] (p. 52). Such MOOCs are a useful supplement to regular higher education. In view of the growing trend of German language at schools and universities, a large number of MOOCs in German/German studies can be expected in the near future.

Digital research on German language in China started in 2008, when the first German language corpus in China, the “Corpus of Interlanguage (German) of Chinese German Studies Students” (KICG), was compiled [37]. In the meantime, digital-based research on the German language in China has produced a lot of results, especially in the field of language acquisition research. Since 2017, the “Chinese German Learner Corpus” (CDLK) has been built at Zhejiang University, which collects the written texts on different topics and in different genres (argumentative, pictorial, descriptive and narrative texts) produced in class within 30 min without any aids by German learners from different years of schools and universities in different regions. According to the error system of Chinese learners of German with great efforts, the CDLK has been annotated at the word and sentence levels, which significantly enhances the corpus scientifically. Teaching and learning German in China is noticeably promoted by the CDLK, and the digitalized research can also be supported by the corpus.

Even during the pandemic, contacts of Chinese schools and universities with their German partners have not ceased, and can be further strengthened as exchanges can take place with the help of the internet without spatial restrictions at flexible times. Since the beginning of the pandemic, a number of lectures, seminars, discussions, and teacher training events have been organized online. The most effective one is the “Virtual German Teacher Days 2020” organized by the Goethe-Institute together with Zhejiang University. The 500 participants had a choice of 23 workshops. Chinese German teachers from all educational contexts were able to exchange views and experiences by attending public lectures and panel discussions. There are also some digital trainings for German teachers, such as DLL of the Goethe-Institute, which are particularly useful because German teachers at universities have long focused on the acquisition of the German language and the teaching of literary, linguistic and regional knowledge, and in most cases lack basic pedagogical and didactic-methodological training [38].

Although LOTEs such as German have not progressed as far as English, significant progresses have been made in the last few years. Because of digital teaching, digital teacher training and digital seminars, LOTE learners and teachers in different regions and schools of different levels have been given relatively equitable opportunities to learn, research, and develop themselves sustainably, so the foreign language education in China can also be developed in a sustainable way.

5. Challenges and Perspectives

In the last five years, four trends towards sustainable development of foreign language education in China are taking place: promotion of sustainable multilingual education, cultivation of sustainable citizens, integration of cultural values, and digitalization for sustainable foreign language education. At the same time, there are also challenges and new perspectives.

5.1. Developing a Systematic Policy of Multilingualism

As mentioned above, it is identified that there is a significant leap in the growth of LOTE programs and learners. However, there are a variety of challenges for the sustainable development of the whole foreign language education in China, including “bold” planning, teacher shortage and teacher’s overwhelming pressure, and poor attraction to learners.

Firstly, the policy of multilingualism should be rationally and systematically planned. The solution for primary and secondary school levels is to select the learners with a talent for language learning as early as possible, and to encourage them to learn LOTEs and then continue their learning at universities, because youngers are sensitive to languages and can learn more than one foreign language at the same time easily. Their learning experience can contribute to building their ability to learn foreign languages throughout their lives. In general, in addition to English, five foreign languages including German, French, Russian, Japanese and Spain can be offered in Chinese middle and high schools, even in some primary schools. However, compared to other countries such as America and Korea, more foreign languages should be encouraged, considering the location advantages of each region: in the cities where there is an ample supply of high-quality teachers of LOTEs and foreign languages are in high demand, such as Beijing and Shanghai, it is recommended that languages with greater coverage such as German and French can be added as the first foreign languages for the learners from an early age. The growth in the number of German learners in recent years has been due to the support for German language education in rapidly developing economic regions. The languages of neighbor countries such as Russian and Vietnamese can be encouraged in border areas [39]. It should be noted that the previous LOTE education at universities was designed in this way. In the case of Yunnan, LOTE programs in languages such as Thai, Burmese, Lao and other languages spoken in Southeast Asian countries are offered by Yunnan University, Yunan Minzu University and other tertiary vocational colleagues such as Yunnan Jiaotong Colleg, and Lincang Teachers’ College [40].

Secondly, many LOTE programs are short of teachers due to the programs’ rapid growth. Even in Beijing Foreign Studies University, the staffing situation of each program is not satisfied [40]. Given the young age of most teachers in these LOTE programs, they have recently started their academic careers and have limited prior education and training. At the same time, they are under overwhelming pressure to manage the balance between teaching and research because of the current Title Rating System in Chinese higher education. A fundamental solution to this problem is to set up specific support assessment systems for LOTE teachers and to provide training opportunities at the national level. Transnational and cross-lingual cooperation for LOTE teacher training can also be considered.

Studies have shown that the deteriorating employment situation in LOTE programs has made the programs less and less attractive for potential applicants, and the true applicants would be of lower academic quality, who may find it difficult to learn these languages and meet graduation requirements [40]. It can be considered that there are special programs to select learners with language talent to study LOTEs and to build good progression pathways to encourage them to continue their learning. For the greater majority of learners, to motivate their interest in learning LOTEs and to encourage their lifelong learning is also important.

In conclusion, a systematic multilingual policy for language placement according to linguistic and regional characteristics, teacher promotion and training, and student recruitment and promotion plays the dominant role for the sustainable development of the foreign language education in China, because the policy-making will take the implications for the sustainable development of a country, society and individuals into account.

5.2. Enhancing Continuity between Schools and Universities in Learning of LOTEs

If LOTEs, such as German, are not only established as an isolated school subject or a university course, but are integrated into a holistic system [41], primarily in order to cultivate sustainable citizens at different levels.

Let’s take German language as an example. Firstly, constant increase in German learners at schools calls for a reform of German education at universities, because many degree programs are designed for beginners, and do not offer a fully-fledged study of German language; rather, they are concerned with German in the sense of an extended language school, in which students focus on grammar and vocabulary [38]. Such courses do not meet the needs of students who have studied German at secondary schools for three to six years. In contrast to attending a language school, such courses should have a scientific level in terms of not only contents but also methodology. The courses should impart competences for autonomous learning with scientific working techniques and for reflective learning. Likewise, such competences that require independent thinking, intercultural ability to act, ability to innovate, ability to analyze and criticize German-language literature and international politics, and ability to deal with digital media are promoted to cultivate sustainable citizens [28]. It would be even better if there are flexible German course programs to meet the needs of students who are beginning or experienced learners of German, which will allow learners to choose the appropriate course according to their level and thus achieve best personal development.

Three series of school textbooks for German subject based on the Hexin-suyang model have already been designed and will have a significant impact on German learning in middle and high schools. In contrast, textbooks for German majors at universities, such as Studienweg Deutsch, are now outdated. They no longer contain up-to-date authentic language materials, and also lack continuity with textbooks for German as a school subject. New textbooks should be developed in line with school textbooks according to the same concept.

In addition, examinations and other performance monitoring procedures for the school subject German are in need of reform. This is especially the case of Gaokao, because this examination is a bridge between high school and university, and it should follow the same concept of foreign language learning at secondary schools and universities. Currently, this examination still follows the old knowledge-oriented concept, leading to exam-oriented German learning at secondary schools. In the future, these examinations should be designed according to the instructions (and also the examples of test items) and requirements of the educational standard, and should be changed to the subject-based Hexin-suyang-model, so as to cultivate sustainable citizens [42]. As mentioned in the above, the number of students registered for Gaogao is increasing. With the introduction of the new standards, a considerable increase in the number of students taking the Gaokao can be expected in the coming years. In this sense, the reform of Gaokao and other performance monitoring procedures is an urgent task of drastic importance.

Only if synergies between curricula, study programs, teaching materials and examinations for LOTEs at schools and universities are established and strengthened, the concept of cultivating sustainable citizens will be put into practice at various stages of LOTE learning, so as to promote sustainable development of individuals in the future.

5.3. Facilitating Effective Integration of Cultural Values in LOTEs

There is now a common understanding in Chinese foreign language education that carrying out education of cultural values in foreign language class can realize the sublimation of teaching materials related to individuals, society, nation and world community, and thus enrich teaching contexts. English, as the most significant foreign language, has made great efforts and achieved a lot in terms of teaching materials and teacher training; however, due to the small number of learners and low impact of LOTEs, it is needed to work on the effective integration of cultural values in LOTE education.

At present, cultural values are being sought to be integrated into LOTE education, particularly as learning contents. German language textbooks work as an example. Although there are no locally developed German language textbooks for secondary schools in use and teachers mostly use the textbooks introduced from Germany, which lack consideration of the needs of Chinese students, three school German textbooks have been completed and are about to be published. These three school textbooks were planned after 2018, so the writers have taken into account the Hexin-suyang concept as well as the needs of the learners in the current social context, with the purpose to cultivate the learners to be sustainable citizens, who can engage with global problems and promote global sustainable development with partners from the whole world. For example, one of the three textbooks Willkommen introduces the 17 Sustainable Development Goals of UN. In the unit of “Environment” in this textbook, students will be asked to put forward their ideas and suggestions on environmental protection to the municipality via a telephone hotline. The aim of this exercise is to encourage students to become aware of common human problems at an early stage, to take an active part in thinking and discussing social issues, to develop a sense of social participation and to develop a spirit of commitment and responsibility. It can be said that this textbook has made efforts and sporadic attempts in this regard; however, these attempts are not enough compared to the current goals pursued by Chinese foreign language education. The German language textbook currently used in Chinese universities, Studienweg Deutsch, was published 15 years ago and is outdated. New textbooks for German majors in universities are being developed and effective integration of cultural values, such as the objectives and principles of different levels, are also expected. In the absence of new teaching materials, teachers should play a role of conductor who can rationally utilize network materials and makes internet a powerful tool to help students build correct sense of values.

Embedding cultural values in foreign language class calls for continuous improvement of teachers’ comprehensive qualities, moral characters and active instruction of students to set up correct values, and adherer to the guiding status of cultural values. Therefore, teachers should adopt various teaching approaches to enable students to make dialectical comparison between Chinese and global values in the process of foreign language learning, so as to make them understand their missions in the new era. In this age of information explosion, it is also necessary and urgent for teachers to make use of modern teaching technology. Teachers are required to realize the combination of foreign language teaching and cultural values by means of multi-media teaching facilities and online teaching platform.

To sum up, in the current situation, effective integration of cultural values into LOTE education is achieved either by developing teaching materials, i.e., by making cultural values an important part of the learning content, or by training teachers, i.e., by empowering them to use the contents of teaching materials or to add cultural values education on their own.

5.4. Promotion of Digitization in Teaching, Research and Learning

Much progress has been made in digitalization of foreign language education in China, but teaching, research and learning of LOTEs such as German still have some shortcomings. The digital teaching, research and learning should be promoted in the future, with the purpose to eliminate inequities between different regions, schools, and even individuals, and finally to promote sustainable development of Chinese foreign language education.

German language is taken as an example again. Above all, digitization in teaching should satisfy the need for qualified teachers of German. Despite the growing dominance of English as the global lingua franca, German often does not serve as a predominant means of communication, but continues to serve as a language for scientific communication in the fields such as philosophy, music, religion, chemistry, car mechanics and medicine [43]. This is why the number of students with German as a second or third foreign language has increased significantly in the last five years and the need for German teachers is greater than ever before. In addition, new German teachers are needed at secondary schools and at the newly established German departments in Chinese universities. In the current training situation, where there is currently no basic pedagogical and didactic-methodical training in German or German studies in China, as mentioned above, the increasing demand can be met by means of digitalization in teaching, such as the promotion and dissemination of online German courses at all language levels.

In addition, there are more research opportunities because of the digitalization: On the one hand, one could focus on new research priorities in digital teaching, such as interaction in synchronous or asynchronous online teaching, learning activities in self-learning, effect of MOOCs, etc., which conversely promote digital teaching. On the other hand, research on the German language can continue to be digitalized and expanded: new procedures for analyzing and using research data are being developed, and new research questions are being posed with constantly evolving methods. The most representative digital research, corpus linguistics of German language, has currently yielded some results, and can be further promoted in the future in a cross-linguistic, cross-institutional, transnational, and interdisciplinary way [37].

Furthermore, the competences of German learners for autonomous learning and the use of digital media should be developed. They can independently select learning materials from the internet, use digital media and opt for a more flexible learning process that suits their language level to save time as well as energy. These competences contribute to sustainable development of individuals.

In a word, digitization is an important measure for the sustainable development of education including foreign language education in current digital society, irrespective of different educational inequities.

6. Conclusions

Given that sustainable development is a widely discussed topic, through a SWOT analysis, we have explored the current trends in the sustainable development of foreign language education in China in the last five years, and the challenges and perspectives of the sustainable development of foreign language education. English language education plays the dominant role in China, but the development of LOTE education is more important for sustainable development. In this study, we use German language as an example of LOTEs.

We have found that Chinese foreign language education currently has four trends: the promotion of multilingualism and promotion of LOTEs constitutes a framework for the sustainable development of foreign language education in China; the goal of talent development for foreign languages has been changed into the concept of cultivating sustainable citizens; in terms of learning and teaching contents, foreign language education integrates the cultural values that share the same connotations as global sustainability; digitalization is an essential measure for eliminating inequalities and achieving sustainable development of foreign language education.

Meanwhile, there are also challenges and perspectives: A rational and systematic policy of multilingualism should be planned, which should indicate the direction of foreign language education in China in the future. In order to cultivate sustainable citizens who are able to respond to various global problems, the curricula, teaching materials and examinations for German at secondary schools and universities should be co-designed to work with each other. Whether in terms of curriculums, textbooks or tests, there should be continuity between secondary schools and universities. In order to integrate the cultural values effectively, more suitable teaching materials should be developed and published; meanwhile, teachers need to be trained for practicing these contents in the class. The digitization in teaching, research and learning should be promoted.

Global issues urgently requires a shift toward the education of sustainable development. With these global trends, the foreign language education in China has made some progress, as it has tried to adapt to the trends. Chinese foreign language education will also continue to develop toward sustainable development. Future developments are yet to be followed, and we will share the experience with our international counterparts in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; Methodology, N.G., E.W. and Y.L.; Validation, N.G.; Formal analysis, N.G. and Y.L.; Investigation, N.G.; Writing—original draft, N.G.; Writing—review & editing, N.G.; Visualization, E.W.; Supervision, Y.L.; Project administration, E.W.; Funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The National Social Science Fund of China, grant number 20BYY103.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Zygmunt, T. Language education for sustainable development. Discourse Commun. Sustain. Educ. 2016, 1, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.; Siege, H. Curriculum Framework: Education for Sustainable Development: A Contribution to the Global Action Programme “Education for Sustainable Development”: Result of the Joint Project of the Standing Conference of the German Ministers of Education and Culture (KMK) and the German Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ); Cornelson: Berlin, Germany, 2016; Available online: https://www.globaleslernen.de/sites/default/files/files/link-elements/curriculum_framework_education_for_sustainable_development_barrierefrei.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Auswärtiges Amt. Deutsch als Fremdsprache Weltweit. Datenerhebung 2020. Available online: https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/blob/2344738/b2a4e47fdb9e8e2739bab2565f8fe7c2/deutsch-als-fremdsprache-data.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Wen, Q. Foreign language education in China in the past 70 years: Achievements and challenges. Foreign Lang. Teach. Res. 2019, 5, 735–745. [Google Scholar]

- He, Q.; Huang, Y.; Qin, X.; Chen, J. Teaching assessment of English in China tertiary education over the past 30 years. Foreign Lang. Teach. Res. 2009, 6, 427–432. [Google Scholar]

- The Chinese Ministry of Education (MOE). Some Suggestions for Strengthening Foreign Language Education; People’s Education Press: Beijing, China, 1979; (In Chinese). Available online: https://pkulaw.com/chl/fb44e7bab7affb45bdfb.html?way=textRightFblx (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- The Chinese Ministry of Education (MOE). General Curriculum Program for General Secondary Schools (2017); People’s Education Press: Beijing, China, 2017; Available online: https://www.ncct.edu.cn/Uploads/File/2022/04/28/%E6%99%AE%E9%80%9A%E9%AB%98%E4%B8%AD%E8%AF%BE%E7%A8%8B%E6%96%B9%E6%A1%88%EF%BC%882017%E5%B9%B4%E7%89%88%EF%BC%89.20220428175601.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Wang, H.; Wang, W. Teaching foreign languages at higher level. In Annual Report on Foreign Language Education in China 2021; Wang, W., Xu, H., Eds.; Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press: Beijing, China, 2022; pp. 7–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y. Exploring dual-foreign-language education in comprehensive universities: Fudan University’s innovation. Foreign Lang. Educ. China 2020, 1, 8–14, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, A.S.L. Language Education in China; Hong Kong University Press: Hong Kong, China, 2005; Available online: https://hkupress.hku.hk/image/catalog/pdf-preview/9789622097513.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Ifediora, C.O.; Idoko, O.R.; Nzekwe, J. Organization’s stability and productivity: The role of SWOT analysis an acronym for strength, weakness, opportunities and threat. Int. J. Innov. Appl. Res. 2014, 9, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. Available online: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/291/89/PDF/N1529189.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Wang, B. Research on new strategy for the development of less commonly taught languages in South Korea: The enlightenment of “Act on the Promotion of Special Foreign Language Education” of South Korea to the education of less commonly taught languages in China. Foreign Lang. Educ. China 2020, 4, 21–31, 90. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Zheng, Y. Multilingualism and higher education in Greater China. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2019, 40, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L. Deutsch. In Annual Report on Foreign Language Education in China 2017; Wang, W., Xu, H., Eds.; Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press: Beijing, China, 2018; pp. 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, L. Deutsch. In Annual Report on Foreign Language Education in China 2021; Wang, W., Xu, H., Eds.; Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press: Beijing, China, 2018; pp. 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L. Editorial: The Power of English and the Power of Asia: English as Lingua Franca and in Bilingual and Multilingual Education. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2012, 4, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.J. Beyond Unreasonable Doubt. Education and Learning for Socio-Ecological Sustainability in the Anthropocene; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2015; Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/365312 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- UNESCO. Position Paper on Education Post-2015. 2014. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000227336 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 2, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The Definition and Selection of Key Competencies [Executive Summary]. 2005. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/definition-selection-key-competencies-summary.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- The Chinese Ministry of Education (MOE). German Language Curriculum Standards for General Secondary Schools (2017); People’s Education Press: Beijing, China, 2017; Available online: https://www.ncct.edu.cn/Uploads/File/2022/04/28/%E6%99%AE%E9%80%9A%E9%AB%98%E4%B8%AD%E5%BE%B7%E8%AF%AD%E8%AF%BE%E7%A8%8B%E6%A0%87%E5%87%86%EF%BC%882017%E5%B9%B4%E7%89%88%EF%BC%89.20220428175426.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Zhao, K. Educating for wholeness, but beyond competences: Challenges to key-competences-based education in China. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2020, 3, 470–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Zhao, S. On students’ key competency in English as a foreign language. Curric. Teach. Mater. Method 2016, 5, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J. Interpreting Core Competencies of English as a Subject in China. IRA-Int. J. Educ. Multidiscip. Stud. 2021, 3, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, X. Interpretation of College German Teaching Guidelines in the Context of the College Foreign Language Teaching Reform. Foreign Lang. World 2020, 5, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Advisory Commission for Foreign Language Philology in Higher Education Institutions, the Chinese Ministry of Education. Teaching Guidelines for Foreign Language Philology in Undergraduate Programs in General Higher Education; Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D. Learning language, learning culture: Teaching language to the whole student. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2020, 3, 519–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, P.R. Teaching Culture: Perspectives in Practice; Heinle & Heinle: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters, B. Language and culture values: Adventures in applied ethnolinguistics. Int. J. Lang. Cult. 2015, 2, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U.; Wang, H.; Ali, I. A sustainable community of shared future for mankind: Origin, evolution and Philosophical foundation. Sustainability 2021, 12, 9352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. Community of shared future for mankind and Chinese traditional culture. China’s United Front. 2016, 8, 72–73. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Report of the World Summit on Sustainable Development, chapter Ⅰ, Annex, Johannesburg Declaration on Sustainable Development, §5. Johannesburg, 2002. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/478154 (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Wang, T. Competence for students’ future: Curriculum change and policy redesign in China. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2019, 2, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J. Eine sprachenpolitische und vergleichende Betrachtung der deutschen Sprache in Japan, Korea und China. Geschichtlicher Überblick, Gegenwartssituation und Zukunftsperspektive. Muttersprache 2020, 3, 216–234. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Ge, N. Digitalisierung in der chinesischen Germanistik am Beispiel der Korpuslinguistik im digitalen Zeitalter. Jahrb. Für Int. Ger. 2019, 2, 191–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lian, F. Die deutsche Sprache in China: Eine aktuelle Bestandsaufnahme. Jahrb. Für Int. Ger. 2017, 2, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, N. The characteristics of foreign language education in German primary and secondary schools their implications. Foreign Lang. Educ. China 2020, 4, 18–25, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Gao, X.; Xia, J. Problematising recent developments in non-English foreign language education in Chinese universities. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2019, 40, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerfeld, V. Strategien zur Verbreitung der deutschen Sprache in China. In Sprache Als Brücke Der kulturen. Sprachpolitik und Sprachwirklichkeit in Deutschland Und China; Jia, W., Miao, Y., Li., J., Eds.; Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press: Beijing, China, 2015; pp. 275–283. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Li, X. Der Hexin-Suyang-orientierte Bildungsstandard des Faches Deutsch an chinesischen Schulen. Jahrb. Für Int. Ger. 2019, 2, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y. Rethinking on the Training of T-shaped Talents of “Minor Languages”. Contemp. Foreign Lang. Stud. 2021, 1, 61–63. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).