1. Introduction

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is the most stable type of foreign capital flow. The global value chain (GVC) has enabled firms to spread their production activities across the globe depending on the availability of competitive resources and competencies [

1]. FDI followed the GVC pattern in most destinations with competitive production factors, closeness to the regional/global production network, as well as prospective markets in the region. Traditionally, FDI has long been acknowledged as a source of economic progress through facilitating the spread of new ideas, skills, technology, and management practices in developing economies [

1,

2,

3]. GVC and FDI can provide foreign technology and a source of positive spillover. They have also offered manufacturing procedures and quality control techniques, generating employment opportunities and access to finance, which is not always easily accessible at the local level [

4,

5,

6]. However, during the last two decades, countries worldwide have opened their doors to attract foreign direct investment using various incentives, such as preferential tax and open economy policies [

7]. On the supply side of the economy, FDI has three effects on the recipient economies: size effect, composition effect, and technical effect [

8,

9,

10]. The home nation’s input and output determine the FDI’s scale effect on economic activity. The composition effect of FDI is indicated by a structural transition from old to contemporary means of production work, such as pre-stage to take-off stage, which changes the industrial mix of recipient nations. In contrast, FDI’s technical influence is centered on transmitting new ideas, information, and superior technologies. On the consumption side of the economy, FDI impacts income inequality and the social welfare of FDI receiving countries [

10,

11,

12].

The relationship between FDI inflows and economic growth has been studied in theoretical and empirical investigations. In particular, most empirical research investigated the cross-country drivers of FDI and diverse variables that influence investment decisions in foreign countries. Previous findings varied across developed and developing countries. Accordingly, net FDI inflows from developed to developing nations differ from those from developing to developed economies. For instance, geographic proximity and institutional environment, as well as macroeconomic conditions, including market size [

13], distance, technological differences, income level, business cost, political stability, and property protection, etc., are the factors affecting investment in a foreign country [

14,

15]. Remarkably, macroeconomic instability and economic policy uncertainty (EPU) lower domestic and foreign investment inflows [

12,

15,

16,

17,

18], reduce production [

19,

20], and decrease the stock of capital [

21,

22] and real estate prices [

23] in the home country. Thus, home and host policy uncertainty become an important source of macroeconomic instability, particularly for emerging and developing economies. Large emerging market economies and developing countries are the major players in the globalized world regarding the rapid pace of economic integration and trade under the global value chain framework. The rapid economic growth, large consumer market, lower wages, and abundant natural resources are attractive to foreign investors in developing economies. However, this research aims to investigate the impact of global and domestic policy uncertainty on the net inflow of foreign direct investment in Asian countries.

Two main factors motivate this research on FDI inflows and policy uncertainty in Asian countries. First, FDI is the most important driving force behind the Asian economic miracles of the last three decades and has provided the capital and expertise to these economies. It contributes to economic growth, creates employment opportunities, and improves productivity and labor force skills through technological transfers. Thus, FDI plays a crucial role today in the global economy and provides additional financial capital to the host countries [

2,

20]. Second, over the last decades, Asian countries have faced subsequent recessions, such as the Asian financial crisis and global financial crisis, governance issues, and policy uncertainty. Most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic badly hit the economies and induced a large construction and FDI flow slowdown. However, compared to the other developing regions, Asian countries still performed better in their share of global FDI inflows. However, the current pandemic uncertainty, trade tensions between China and the United States, and regional political instability have disrupted global FDI inflows. New and noteworthy investment and trade policies are needed to further encourage and promote FDI inflows in Asian countries. The limited literature highlights the impact of domestic and foreign policy uncertainty on FDI inflows and how the financial development mediates the relationship between domestic and foreign policy uncertainty in Asian countries and FDI inflows. Thus, this study fills the gap by exploring the links between domestic and foreign policy uncertainty in FDI inflows in 48 Asian countries from 2000 to 2020.

Furthermore, we look at the relationship between the macroeconomic determinants of FDI, such as real GDP growth, GDP per capita, trade, inflation rate, population, and employment rate. To measure policy uncertainty, we used the recently developed Economic Policy Uncertainty Index [

24,

25]. The current study used an alternative method to measure domestic policy uncertainty, such as political risk.

Theoretically, this study sheds light on the institutional theory, which explains the institutional structure and behavior of the investors and the determinants of FDI flows. According to the theory, the countries engaged in international investment and FDI flows are determined by institutional factors, such as business cost, macroeconomic environment, political stability, institutional quality, transparency, and property protection. Thus, our findings contribute to the institutional theory, which explains the constraints to FDI inflows, the role of state interference, institutional support, unpredictability of public policies, and political risk. On the empirical side, this study contributes to the literature in two ways. First, the FDI literature explains the extensive list of cross-border determinants of foreign direct investment [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Among these, the main determinants of FDI are income level, population, institutional quality, GDP growth, liberalization policies, and natural resource endowment. These empirical studies have shown mixed results, and the determinants have varied regarding regions and countries [

32]. However, we depart from the current literature in that we focus on policy uncertainty and investigate the impact of policy uncertainty on domestic and foreign investment, particularly on foreign direct investment. We include macroeconomic variables in our models, such as GDP growth, GDP per capita, exchange rate, trade openness, inflation rate, and the unemployment rate, as significant determinants of FDI. Second, our paper also contributes to the recent international investment and macroeconomic literature with regard to the role of financial institutions, focusing on the role of financial development in mitigating the negative effect of domestic and global policy uncertainty.

The rest of the paper is divided into the following sections. The second section offers a survey of the theory and empirical literature. The third section presents the data and methodology of the study, including the theoretical framework, econometric model, sources of data, and definition of variables. The fourth section involves the estimation of the econometric model and empirical findings. The fifth section concludes the overall results and provides some policy implications.

2. Some Stylized Facts from Asia: Inward and Outward FDI Flows

Since the 1990s, the inflow and outflow of foreign direct investment have increased dramatically worldwide, particularly in developing countries. After the 1990s, many developing countries removed restrictions and implemented bilateral investment policies to attract foreign direct investment and trade. This led to rapid FDI, business, and investment expansion in many developing countries, particularly in Asia. According to the World Investment Report (Ref. [

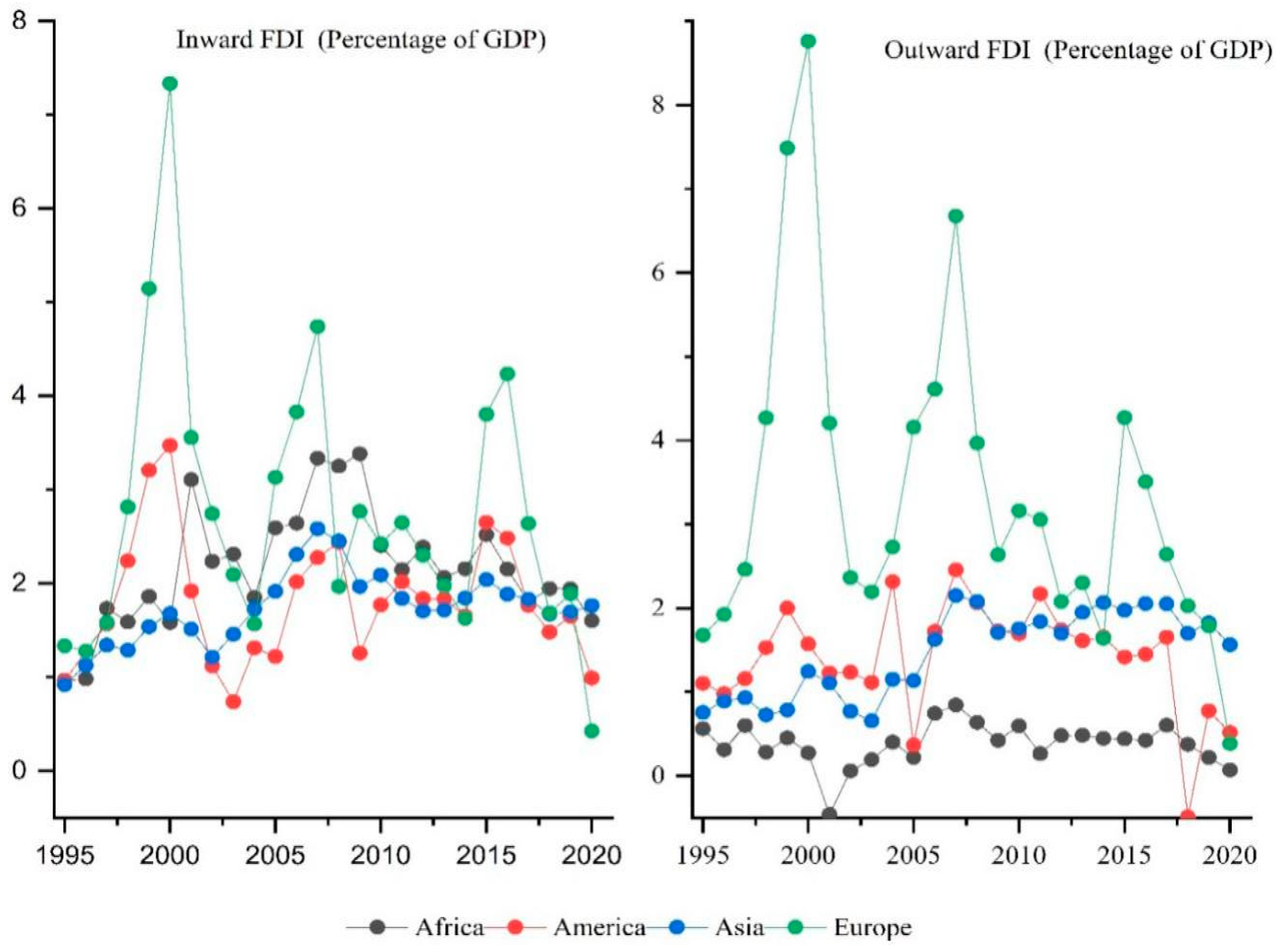

33]), the Asian region was the largest recipient of FDI inflows in 2018. As

Figure 1 demonstrates, Europe and America were the largest source of both inflows and outflows of FDI in the 1990s. The Asian countries’ shares significantly declined during the 1990s due to the Asian financial crisis (AFC). After the AFC, the Asian countries raised their shares and received large shares of world FDI inflows. At the same time, however, the contribution of both inward and outward FDI to GDP has been increasing in the Asian region over the last two decades; in other regions of the world, it has shown a decreasing trend, as shown in

Figure 1.

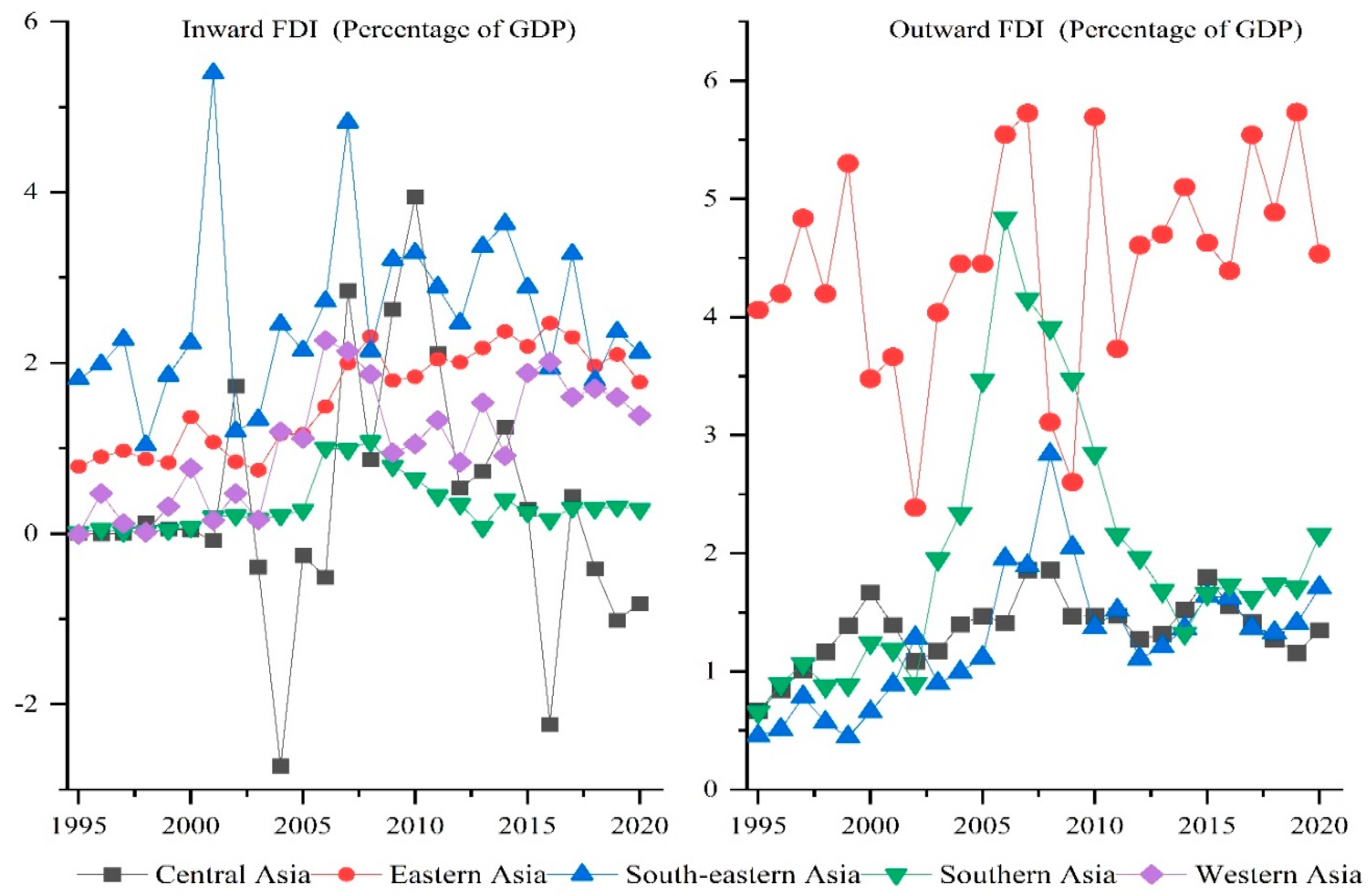

Regarding the geographical pattern, the inward and outward FDI flows differ among Asian countries.

Figure 2 shows both inward and outward FDI in five Asian regions. Among the five Asian regions, southeastern Asia has the largest inward FDI, while eastern Asia is the most significant outer FDI region. This shows that southeastern Asian countries are the most preferred location for foreign investors and a large amount of FDI outflow from eastern Asian countries. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused a decline in global FDI flows of 49% in the first quarter of 2020 compared to the previous year. In Asia, FDI inflows dropped from 45% to 35%, and its share of global FDI outflows dropped from 52% to 41% [

34]. However, the Asian region has maintained the largest FDI flows. Among the Asian countries, China, Japan, India, Malaysia, and Hong Kong are the countries with the largest FDI flows [

35,

36].

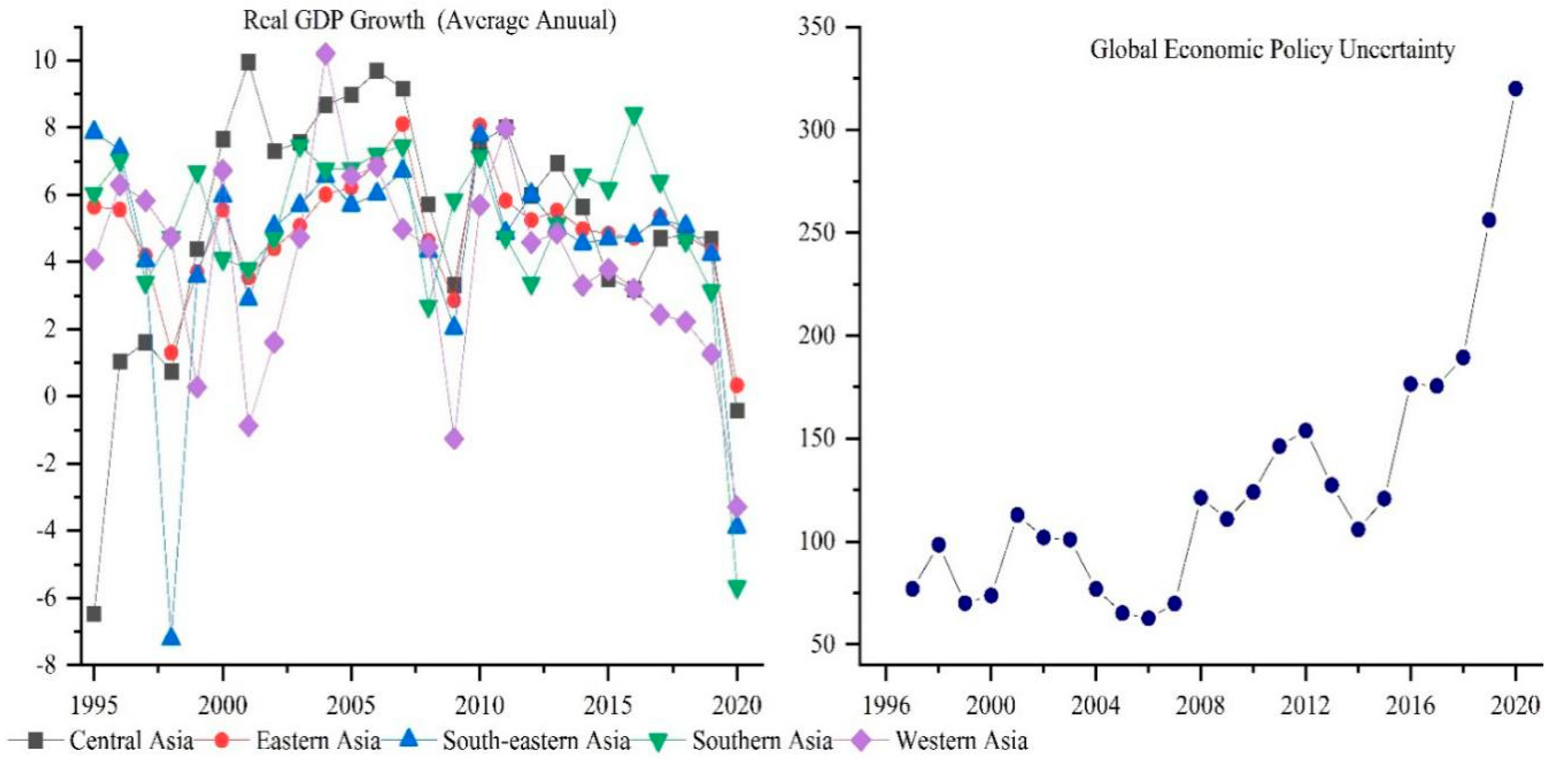

The Asian developing countries have grown impressively over the last two decades. The Asian countries’ real GDP had expanded four-fold since 1980, but the real per capita income in Asian developing countries remains below the world average. According to the International Monetary Fund [

37] economic outlook report, Asia is the fastest growing region in the world, with a GDP growth of 6.4 percent in 2021;

Figure 3 shows the regional real GDP growth of five Asian areas. Accordingly, many factors contribute to GDP growth, such as favorable geography and structural characteristic, trade openness, and FDI inflows. Therefore, Asia, particularly the emerging Asian countries in eastern and western Asia, influences the global economy and achieves robust economic growth.

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Several factors, including natural calamities, geo-political instability, trade wars, and changes in geo-economics, have brought the effects of economic policy uncertainty on FDI inflows to the limelight in a new context. Our finding contributes to the growing body of literature examining the relationship between economic policy uncertainty, foreign capital flows, and investor decision in 48 Asian countries from 2000 to 2020. We use the inward FDI and domestic investment data as the primary outcome variables, while global economic policy uncertainty and domestic policy uncertainty data are the primary variable of the study. The FDI and domestic investment data enable us to identify the effect of external and internal uncertainty. We used the generalized moment method, which also produces robust empirical results.

Our findings suggest that increasing policy uncertainty at the global level has a significant negative impact on inward FDI in our sample countries. We use the global economic policy uncertainty (GEPU) index to intensify foreign and domestic investment policy uncertainty. Furthermore, we employed the system GMM method and lagged dependent variable as an instrument to resolve endogeneity and serial correlation in residuals in our baseline findings. We investigate the impact of financial development in explaining how increased global policy uncertainty and domestic uncertainty decrease inward FDI and domestic investment. The results show that FD has no mitigating role in the negative effect of international economic policy uncertainty on inward FDI. In contrast, it has a negative role in mitigating the adverse effects of domestic policy uncertainty.

Domestic policy uncertainty has a negative impact on inward FDI in the whole sample and subsample countries in Asia. In addition, our results show that foreign investment is more sensitive than domestic investment. The impact of domestic and global uncertainty on inward FDI is greater than domestic investment. In addition to these effects, trade, GDP growth, GDP per capita, population, inflation rate, employment rate, and financial development are the main determinants of foreign direct investment across 48 Asian countries.

6.1. Policy Recommendations

Our findings have many policy implications, and we provide the following policy recommendations.

Despite economic challenges and geo-economic rhetoric, FDI continues to flow to Asian countries. However, policymakers should emphasize the mitigating mechanism of uncertainty by controlling the negative effect of policy uncertainty on FDI, promote FDI inflows, and attract and encourage foreign investors. Geo-political rivalry and decoupling of the global supply chain are further threatening economic uncertainty in the global market. Cooperation among the major economic powers in targeting the policies toward financial stability is needed to create an FDI-friendly business eco-system.

Decoupling of the global supply chains and geo-economic considerations may shift certain FDI destinations but may not result in any drastic shifts. FDI may leave some markets, such as China, and move to other Asian markets, such as Vietnam, India, Bangladesh, and southeastern Asian markets. Policymakers need to take these shifts into consideration and develop their economic and financial policies to woo a higher share of FDI to their respective economies.

Our findings imply that a well-developed financial system assists in the management of detrimental effects of economic uncertainty. Policymakers should go above and beyond in their planning to ensure a well-functioning financial system, which reduces the negative impact of uncertainty on FDI. Finally, it is critical to keep a careful eye on policy uncertainties both at home and abroad. Other aspects of the economy, such as trade liberalization, inflation, and domestic employment levels, should be considered by policymakers. Low inflation and unemployment rates and low political risk encourage FDI inflow into Asian countries. The role of institutions has become essential in increasing the attractiveness of a local economy, and the government needs to take proactive steps to encourage FDI inflows.

6.2. Limitation of the Research and Future Direction

Our research has two limitations. First, the findings of this study are generalized and are comparable to Asian developing countries. Second, the sample of countries is limited. Therefore, this study can be extended to increase the sample size of countries for the analysis of high-, low-, and middle-income countries. Economic structure might also be a determining factor in attracting FDI. For example, a manufacturing-focused economy will attract more FDI than a service sector economy in the developing Asian markets. More variables may be analyzed in the future to determine their effect on FDI inflow in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. In addition, with regard to the methodology of the study, machine-learning techniques can improve the quality of the model. Furthermore, the roles of institutions, trade policy, and export and import diversification in economic policy uncertainty can be added for examination.