Effects of Organizational Justice on Employee Satisfaction: Integrating the Exchange and the Value-Based Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

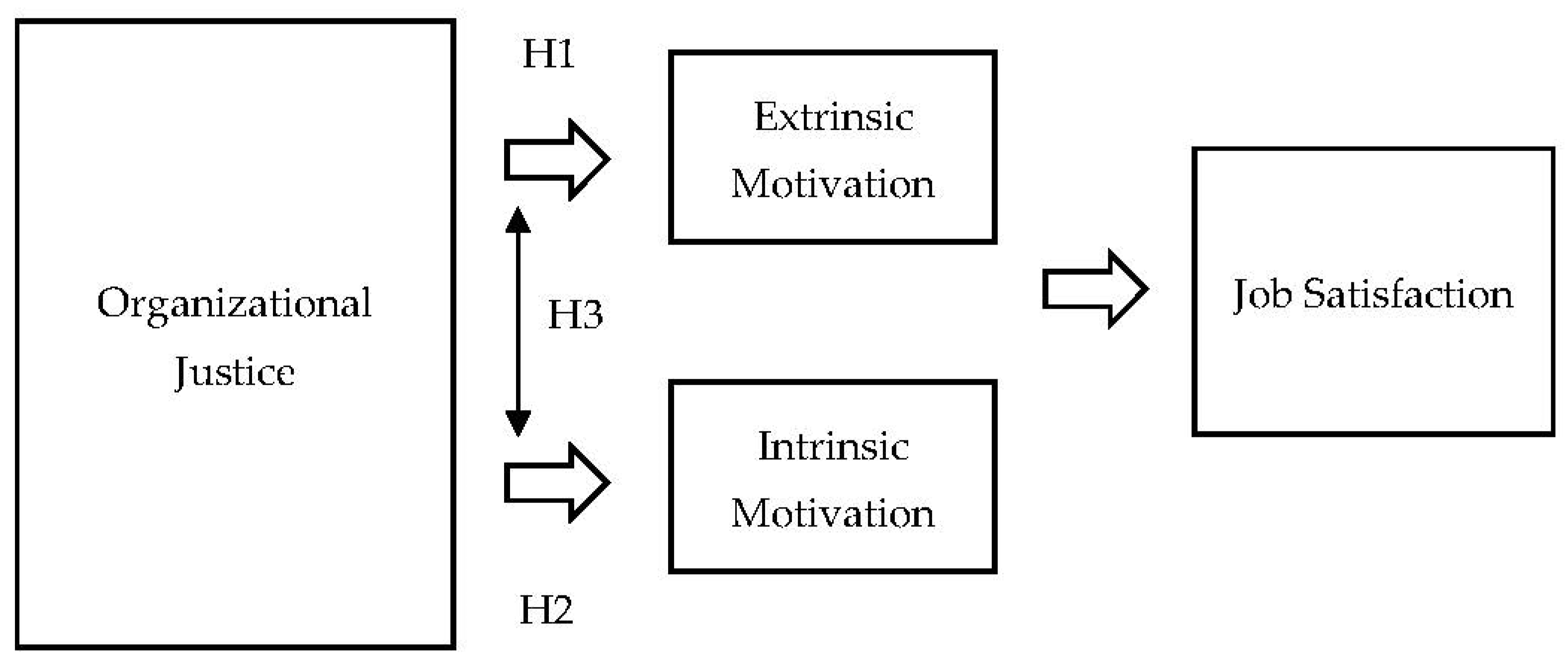

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Social Exchange Theory and Extrinsic Motivation

2.2. Value-Based Management Theory and Intrinsic Motivation

2.3. Relative Strengths of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

3. Methods

3.1. Data and Sample

3.2. Analysis

3.3. Measurement

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

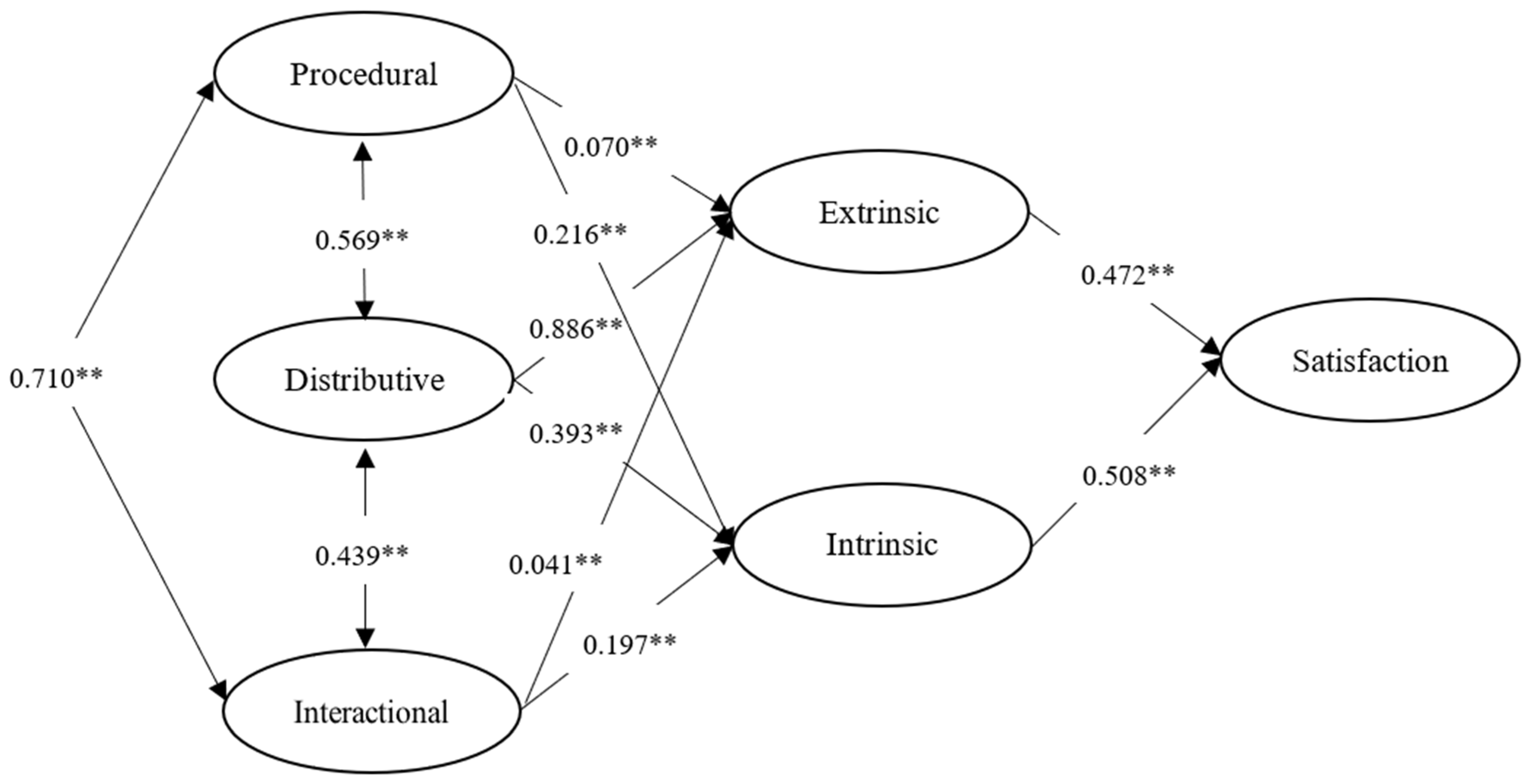

4.2. Structural Model

5. Discussions and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Implications for Sustainability

6. Limitation and Avenue for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ren, T. Value congruence as a source of intrinsic motivation. Kyklos 2010, 63, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J.; Porter, C.O.; Ng, K.Y. Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.S. Inequity in social exchange. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1965, 2, 267–299. [Google Scholar]

- Farh, J.L.; Earley, P.C.; Lin, S.C. Impetus for action: A cultural analysis of justice and organizational citizenship behavior in Chinese society. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 421–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, R.H. Relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviors: Do fairness perceptions influence employee citizenship? J. Appl. Psychol. 1991, 76, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, A.; Kumar, K.; Rani, E. Organizational justice perceptions as predictor of job satisfaction and organization commitment. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2009, 4, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, R.; Hang-Yue, N.; Foley, S. Linking employees’ justice perceptions to organizational commitment and intention to leave: The mediating role of perceived organizational support. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2006, 79, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlin, D.B.; Sweeney, P.D. Distributive and procedural justice as predictors of satisfaction with personal and organizational outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.; Heron, P. The difference a manager can make: Organizational justice and knowledge worker commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 16, 383–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay-Warner, J.; Reynolds, J.; Roman, P. Organizational justice and job satisfaction: A test of three competing models. Soc. Justice Res. 2005, 18, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeConinck, J.B.; Stilwell, C.D. Incorporating organizational justice, role states, pay satisfaction and supervisor satisfaction in a model of turnover intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.; Sire, B.; Balkin, D.B. The role of organizational justice in pay and employee benefit satisfaction, and its effects on work attitudes. Group Organ. Manag. 2000, 25, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R.J.; Kohlmeyer, J.M. Organizational justice and turnover in public accounting firms: A research note. Account. Organ. Soc. 2005, 30, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Budhwar, P.S.; Chen, Z.X. Trust as a mediator of the relationship between organizational justice and work outcomes: Test of a social exchange model. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.F. The relationships of organizational justice, social exchange, psychological contract, and expatriate adjustment: An example of Taiwanese business expatriates. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 1090–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prysmakova, P. Institutional antecedents of public service motivation: Administrative regime and sector of economy. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2021, 32, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. The contrary effects of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations on burnout and turnover intention in the public sector. Int. J. Manpow. 2018, 39, 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Byrne, Z.S.; Bobocel, D.R.; Rupp, D.E. Moral virtues, fairness heuristics, social entities, and other denizens of organizational justice. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 58, 164–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babakus, E.; Yavas, U.; Karatepe, O.M. The effects of job demands, job resources and intrinsic motivation on emotional exhaustion and turnover intentions: A study in the Turkish hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2008, 9, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.S.; Hargis, M.B. What motivates deviant behavior in the workplace? An examination of the mechanisms by which procedural injustice affects deviance. Motiv. Emot. 2017, 41, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice: Revised Edition; Belknap: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps, C.; Rinfret, N.; Lagacé, M.C.; Privé, C. Transformational leadership and change: How leaders influence their followers’ motivation through organizational justice. J. Healthc. Manag. 2016, 61, 194–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannam, K.; Narayan, A. Intrinsic motivation, organizational justice, and creativity. Creat. Res. J. 2015, 27, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Mondejar, R.; Chu, C.W. Accounting for the influence of overall justice on job performance: Integrating self-determination and social exchange theories. J. Manag. Stud. 2015, 52, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch Jr, J.G.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata-Phelan, C.P.; Colquitt, J.A.; Scott, B.A.; Livingston, B. Procedural justice, interactional justice, and task performance: The mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2009, 108, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.F. Effects of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on employee knowledge sharing intentions. J. Inf. Sci. 2007, 33, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weibel, A.; Rost, K.; Osterloh, M. Pay for performance in the public sector—Benefits and (hidden) costs. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2010, 20, 387–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crewson, P.E. Public-service motivation: Building empirical evidence of incidence and effect. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 1997, 7, 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould-Williams, J.S.; Mostafa, A.M.S.; Bottomley, P. Public service motivation and employee outcomes in the Egyptian public sector: Testing the mediating effect of person-organization fit. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2015, 25, 597–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Public service motivation and organizational citizenship behavior in Korea. Int. J. Manpow. 2006, 27, 722–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Roch, S.G.; Shannon, C.E.; Martin, J.J.; Swiderski, D.; Agosta, J.P.; Shanock, L.R. Role of employee felt obligation and endorsement of the just world hypothesis: A social exchange theory investigation in an organizational justice context. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 49, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekleab, A.G.; Takeuchi, R.; Taylor, M.S. Extending the chain of relationships among organizational justice, social exchange, and employee reactions: The role of contract violations. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Cropanzano, R. The mediating effects of social exchange relationships in predicting workplace outcomes from multifoci organizational justice. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2002, 89, 925–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, S.S.; Lewis, K.; Goldman, B.M.; Taylor, M.S. Integrating justice and social exchange: The differing effects of fair procedures and treatment on work relationships. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.J.; Perry, J.L. Intrinsic motivation and employee attitudes: Role of managerial trustworthiness, goal directedness, and extrinsic reward expectancy. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2012, 32, 382–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. Organ. Dyn. 1990, 18, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Steidlmeier, P. Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. Leadersh. Q. 1999, 10, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatman, J.A. Improving interactional organizational research: A model of person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finegan, J.E. The impact of person and organizational values on organizational commitment. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 73, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meglino, B.M.; Ravlin, E.C.; Adkins, C.L. A work values approach to corporate culture: A field test of the value congruence process and its relationship to individual outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberghe, C.; Peiró, J. Organizational and individual values: Their main and combined effects on work attitudes and perceptions. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1999, 8, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, B.J.; Bynum, B.H.; Piccolo, R.F.; Sutton, A.W. Person-organization value congruence: How transformational leaders influence work group effectiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estreder, Y.; Rigotti, T.; Tomás, I.; Ramos, J. Psychological contract and organizational justice: The role of normative contract. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2020, 42, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1976, 16, 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Oh, I.S.; Courtright, S.H.; Colbert, A.E. Transformational leadership and performance across criteria and levels: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of research. Group Organ. Manag. 2011, 36, 223–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Rich, G.A. Transformational and transactional leadership and salesperson performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2001, 29, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trottier, T.; Van Wart, M.; Wang, X. Examining the nature and significance of leadership in government organizations. Public Adm. Rev. 2008, 68, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, S.; Resh, W.G.; Moldogaziev, T.; Oberfield, Z.W. Assessing the past and promise of the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey for public management research: A research synthesis. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillier, J.G. The impact of teleworking on work motivation in a US federal government agency. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2012, 42, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Thoresen, C.J.; Bono, J.E.; Patton, G.K. The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curry, J.P.; Wakefield, D.S.; Price, J.L.; Mueller, C.W. On the causal ordering of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Acad. Manag. J. 1986, 29, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, P.G.; Foti, R.J.; Hauenstein, N.M.; Bycio, P. Are the best leaders both transformational and transactional? A pattern-oriented analysis. Leadership 2009, 5, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, S. Organizational justice as an outcome of diversity management for female employees: Evidence from US federal agencies. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2016, 12, 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Thibaut, J.W.; Walker, L. Procedural Justice: A Psychological Analysis; L. Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal, G.S. What should be done with equity theory? Soc. Exch. 1980, 27–55. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED142463.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Lee, H.W. Performance-based human resource management and federal employee’s motivation: Moderating roles of goal-clarifying intervention, appraisal fairness, and feedback satisfaction. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2019, 39, 323–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paarlberg, L.E.; Lavigna, B. Transformational leadership and public service motivation: Driving individual and organizational performance. Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 70, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlicki, D.P.; Latham, G.P. Leadership training in organizational justice to increase citizenship behavior within a labor union: A replication. Pers. Psychol. 1997, 50, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harackiewicz, J.M.; Barron, K.E.; Tauer, J.M.; Carter, S.M.; Elliot, A.J. Short-term and long-term consequences of achievement goals: Predicting interest and performance over time. J. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 92, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienesch, R.M.; Liden, R.C. Leader-member exchange model of leadership: A critique and further development. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 618–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cugueró-Escofet, N.; Ficapal-Cusí, P.; Torrent-Sellens, J. Sustainable human resource management: How to create a knowledge sharing behavior through organizational justice, organizational support, satisfaction and commitment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, M.; Izhar, Z.; Kazmi, Z.A. Organizational justice and employee sustainability: The mediating role of organizational commitment. SEISENSE J. Manag. 2020, 3, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Intrinsic Motivation | Extrinsic Motivation | Overall Satisfaction | Procedural Justice | Distributive Justice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic Motivation | 4.052 | 0.794 | |||||

| Extrinsic Motivation | 3.381 | 1.042 | 0.645 ** | ||||

| Overall Satisfaction | 3.785 | 0.989 | 0.744 ** | 0.766 ** | |||

| Procedural Justice | 3.748 | 1.031 | 0.593 ** | 0.740 ** | 0.706 ** | ||

| Distributive Justice | 3.316 | 0.990 | 0.612 ** | 0.867 ** | 0.708 ** | 0.723 ** | |

| Interactional Justice | 4.076 | 0.875 | 0.590 ** | 0.700 ** | 0.675 ** | 0.706 ** | 0.670 ** |

| Mediating Variable | ||

|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | Intrinsic Motivation | Extrinsic Motivation |

| Distributive Justice | 0.200 | 0.418 |

| Procedural Justice | 0.110 | 0.033 |

| Interactional Justice | 0.100 | 0.019 |

| Total Effect | 0.410 | 0.470 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, H.-W.; Rhee, D.-Y. Effects of Organizational Justice on Employee Satisfaction: Integrating the Exchange and the Value-Based Perspectives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075993

Lee H-W, Rhee D-Y. Effects of Organizational Justice on Employee Satisfaction: Integrating the Exchange and the Value-Based Perspectives. Sustainability. 2023; 15(7):5993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075993

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Hyung-Woo, and Dong-Young Rhee. 2023. "Effects of Organizational Justice on Employee Satisfaction: Integrating the Exchange and the Value-Based Perspectives" Sustainability 15, no. 7: 5993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075993

APA StyleLee, H.-W., & Rhee, D.-Y. (2023). Effects of Organizational Justice on Employee Satisfaction: Integrating the Exchange and the Value-Based Perspectives. Sustainability, 15(7), 5993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075993