Abstract

Marine development and eco-environmental management have received increasing attention over the past two decades, however, no effective universal approach has been established to achieve marine development without destroying marine ecosystems. This study discusses the integrated ocean management (IOM) for meeting the sustainable development goal (SDG14) through the following four aspects: the marine eco-environment foundation, market mechanism, management support, and space consideration. Our findings highlight how to enhance the coastal and marine areas management efficiency to achieve ecological and socioeconomic values for sustainable development through the benign interaction of marine ecosystem and socioeconomic systems. The presented case study examines the IOM framework for achieving SDG14 in the Bohai Sea. Furthermore, content analysis and semi-structured interviews were conducted. The framework is theoretically and empirically explored in light of the Bohai Sea’s management, focusing on the role of the government and incentive. Further, issues preventing effective IOM are highlighted and a framework for optimizing the IOM implementation to better balance the interests of various industries is suggested. When implementing the IOM framework, each region should fully play to its own advantages and push forward with some focused aspects first. The long-term effect of the Bohai Sea’s management may need time to be verified, and the role of the market mechanism and multi-interest coordination mechanism need more special attention for the Bohai Sea in the future.

1. Introduction

“The oceans and seas are essential for social well-being” [1]. More than 40 percent of the world’s population, or 3.1 billion people, live within 100 km of the ocean. Whether a country is landlocked or coastal, it has a direct connection to the sea through rivers, lakes and streams. The oceans provide more than 60 percent of the world’s gross national product (GNP) in benefits. “Oceans are the point at which planet, people, and prosperity come together. And that is what sustainable development is about” [1]. Sustainable development goals (SDGs) and integrated ocean management (IOM) have greatly improved marine development strategies and management policies. Reducing marine exploitation and increasing protection are the most important objectives [1] to systematically achieve a benign interaction between humans and the marine ecosystems.

The IOM aims regarding socioeconomic development are based on prompting healthy marine management (including coastal and marine ecology, environments, and resources), which focuses on enabling a harmonious relationship between marine ecosystem services and economic development [2,3]. Approaches such as market-based instruments (MBIs), ecosystem-based management (EBM), marine spatial planning (MSP), integrated coastal zone management (ICZM), and sea–land/land–sea management (SLM) provide theoretical and practical support for the IOM, as they are the most important achievements of mankind in this field. Moreover, these approaches facilitate the IOM implementation for achieving SDG14 (SDG14: conserve and sustainably use oceans, seas, and marine resources), which is an important goal for achieving sustainable development). (Please refer to the Table A1 in Appendix A for more details about the concepts above if necessary.)

Marine ecosystems play an important role in human development; however, there are several challenges, including the unidentifiability and uncertainty of the system, biophysical dynamics between the land and sea, and ecosystem management complexity across geographic and institutional boundaries. IOM has been recognized by the International Maritime Organization as an ideal strategy to deal with these challenges [2]. Some developed countries (such as Norway, United States) and developing countries (such as China) primarily use IOM in the process of marine management and have gradually applied it in coastal zone economic development to solve industrial, economic, and environmental conflicts. To extract petroleum products (oil and gas) in the Barents Sea, Norway designed a marine development plan as early as 2006 to balance the interests of various industries (such as the energy and fishery industry) and the relationship between economic development and marine ecosystem management. The plan involved rezoning the sea, rearranging shipping routes, demarcating areas for oil development and energy projects, fishing and biodiversity reserves, and creating rules for the eco-environment compensation, among others [4]. At the beginning of the 21st century, Australia initiated comprehensive management of the Great Barrier Reef, delineating tourism areas and coral reef areas (to protect biodiversity) in the space, and achieved a virtuous cycle of tourism and marine ecosystem management [5].

ICZM, MSP, EBM, and MBI for marine management are attempting to transcend traditional approaches to address marine-related issues using a linear perspective. However, this can cause decision incoherence, costing the opportunities to achieve sustainable development. For example, EBM is described as “the integrated management of marine systems based on ecological knowledge to achieve sustainability of ecosystem services”, but it lacks the tools for operability and implementation. Therefore, EBM fails to integrate into the market [6] and remains theoretical. Until recent years, features of various theories and approaches have been combined and incorporated into marine management. For example, the feasibility of ICZM and SLM legal models were proposed in empirical studies; MSP was incorporated into MBI for ecosystem services [7], and a framework of ICZM to serve the coastal development was proposed [8]. The idea of IOM, which aims to establish a benign interactive relationship and healthy cooperation between marine ecosystems and the human social-economic systems was proposed based on these advances. Winther et al. described the role of IOM in marine development and incorporated ICZM, MSP, EBM, and MBI into IOM [2,3]. This approach provided flexible in response options and effectively readdressed the inevitable limitations of individual approaches. Space planning and zoning can effectively solve conflicts between eco-environmental governance and marine development, in addition to providing insights for solving the marine eco-environment crisis and alleviating pressure on coastal resources [9]. To achieve this, the principles of MSP should be followed. Moreover, if pollution, waste discharge, ecological damage, and other environmental issues are designed as commodities, such as property rights (including mineral exploitation rights, pollution rights, emission rights, etc.), then the market mechanism resource allocation function can be used as a solution [10,11,12]. Economically, IOM is more cost-effective and easier to operate ecologically, thereby achieving SDG14.

The purpose of this study was to explore the application of IOM in coastal and marine sustainable development. For this, we established a framework to study IOM for SDG14 from four aspects: the marine eco-environment foundation, the market mechanism, management support, and space consideration, with a particular focus on China.

During the last three decades, China has experienced rapid development, however, complex environmental and ecological pressures (such as pollution and loss of biodiversity) have led to unsustainable development [13]. In recent years, China’s management of the Marine Ecological Civilization has aided in fulfilling the goals of SDG14 [14,15]. Thus, China provides an interesting case for disseminating how IOM can be implemented in national policies by focusing on ecosystem service.

In this study, Section 2 expounds on the IOM theoretical significance for achieving SDG14. Based on the marine economy sustainable development achieved by IOM [3], it introduces a framework for IOM to meet SDG14, which can guide further empirical research. Section 3 introduces a case study of the Bohai Sea. The research strategy for analyzing the IOM of the Bohai Sea is explained in Section 4, and Section 5 discusses the results. We conclude with a reflection of the advantages and disadvantages of the current IOM framework in view of China’s Marine Ecological Civilization, and suggest some measures to optimize the Bohai Sea management.

2. IOM for SDG14

2.1. Understanding IOM for SDG14

SDG14 calls on states and communities globally to “Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development” [16], which involves tackling the multi-angle and multi-dimensional problems related to marine resources, ecology, and environments in marine development. SDG14 is underpinned by nine specific targets addressing marine pollution and conservation, ocean acidification, fisheries, benefits for Small Island Developing States (SIDS), small-scale fisheries, scientific knowledge, marine research, and international law [16,17]. Development issues, and the rights and interests of future generations, in addition to the issues regarding equity in land, sea, and human space are considered as part of SDG14. Moreover, it also involves the harmonious coexistence between the development of humans and marine ecosystems, and is an equity issue for the co-existence of human beings and other organisms such as marine animals and plants.

Both SDGs and IOM recognize that the purpose of marine development is to promote social and economic progress while maintaining the overall ecosystem health and resilience. In terms of the marine ecosystem resilience and environmental carrying capacity, EBM (as an approach for IOM) emphasizes the compatibility and exclusiveness of ecosystem functions. Further, human activities should prioritize the overall ecosystem health and sustainable use of marine resources over certain development activities or special interests. MBIs achieve the optimal allocation of resources, minimum transaction costs, and maximum resource efficiency. Reasonable taxation, subsidies, and other measures can restrict or encourage specific aspects of marine development to a certain extent, which can promote the rational utilization of the ocean to maximize fishery, aquaculture, and tourism economic benefits in coastal countries, in addition to reducing the cost of ecological environments and effectively promoting stakeholders’ participation. Marine spatial planning has many dimensions, including the space, time, and ecosystem, and can change traditional marine management by facilitating EBM and MBIs centered on marine ecosystems. In recent years, ICZM has allowed the integration of coastal and offshore water ecosystem services enabling the inclusion of marine ecosystems into human social and economic systems.

In conclusion, IOM-related approaches provide solid foundations for studying IOM. Understanding the complexity of IOM is necessary to achieve SDG14; therefore, we discuss the current framework and propose an analytical framework to guide further empirical analysis.

2.2. The Framework of IOM

A summary of the IOM framework is shown in Table 1. For SDG14, the IOM is related to marine ecology, environments, resources, economic development, and marine governance, drawing on the qualitative research of IOM, EBM, MSP, MBI, ICZM, SLM, and ocean economics. The framework provides a structure for IOM implementation and insights into the associated practices.

Table 1.

The IOM Framework.

2.2.1. Ecosystem-Based Management

Protecting ecosystem structure and function for the maintenance of ecosystem services should be the main objective of the ecosystem-based approaches, which is one of the Malawi principles in the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) [18]. Marine resource management focuses on marine ecosystem stability (health), productivity, and resilience [9], in addition to all interactions within the marine ecosystem and the cumulative impact of different factors, such as human interactions and linkages [19]. The internal subsystems of an ecosystem are interconnected, and human activities targeting one subsystem can have an impact on others. Ecosystem components, such as air, land, and sea, are interconnected and interdependent; therefore, EBM should maintain the ecosystem integrity [20,21]. In addition to tending to the structure and function of ecosystems, EBM should protect key ecosystem processes. As a member of global ecosystems, it is within the best interests of humans to the limit activities that negatively impact the environment and carry out only necessary marine eco-environmental monitoring.

2.2.2. Marketization

At a time when the market economy is widely recognized, the Law of Value may be the most effective way to promote social and economic development through marine activities—the goal of both SDG14 and IOM. The market mechanism has penetrated many fields, including marine development and marine economy. Marine resources enter the economic system in the form of commercialization and marine ecological services through market transactions, such as those in fishery, shipping, oil development, and marine tourism [22]. In addition, marine industry development promotes the accumulation of production means in coastal zones, the construction of ports, and the development of coastal cities [23]. Thus, the Law of Value has played an important role in promoting marine ecosystems to provide a livelihood for humans.

Marketization can be used to enhance marine resource rational participation in social and economic system activities, such as the land-based administrative division categorizing the sea as “Commons”. Such externalities require the proper intervention to ensure a healthy market. This requires the internalization of the costs and benefits of specific ecosystems to reduce the market distortions that adversely affect biodiversity and ecological health. Therefore, externality characteristics must be modified before marine resources enter the market system. Previous studies have assessed various marine ecological services, such as environmental management, which are difficult to commercialize. Artificial prices of externalities and measurable regulatory elements (such as sea use, fishing quotas, and carbon credits) have been extensively piloted [10,24,25]. The operation of market regulation, such as empowerment (pollution rights and ecological compensation), the establishment of trading platforms, and venues and trading rules (administrative licensing and auction) are efficient.

2.2.3. Management Support

Legal systems create surroundings for defining and advancing cross-sectoral, long-term, ocean-related goals, and for IOM within countries or between regions. National administrative regulations, administrative orders, cooperation agreements, and cooperation plan frameworks among regions are all effective means to guide marine development and management [2]. Integrity and adaptability are important principles of the IOM. Regulations for marine governance, such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, are rules for the cooperation and guiding documents for global and regional maritime issues [3,26]. At the local level, an approach suited to the different environment, socioeconomic, and governance systems of each region incorporating local knowledge and ensuring active community participation [16] is needed, particularly in developing countries and SIDS. In addition, the multilateral problem-solving approach is central for implementing regional agreements and mechanisms. Cooperation and coordination play a key role in addressing the external factors involved in coastal and marine resources, the environment, and interest groups.

Specific organizations and policy systems guarantee the smooth operation of the IOM. Institutional capacity is a key element in enhancing ocean governance; in particular, strengthening institutional enforcement is at the forefront of the current global ocean debate [9] and is a top priority in the international agenda [2]. Inadequate knowledge and weak management enforcement prevent coastal states from fulfilling marine rights and obligations. The 2017 Global Marine Science Report indicated that many countries lack the basic scientific knowledge to support their efforts in marine governance [27].

Thus, the knowledge and information regarding marine ecosystems and economic activities are the foundation for successful execution. New technology has revolutionized how governments monitor and regulate misconduct at sea. The Global Fisheries Watch is an example of how new technology and transparency can improve sustainable governance, by tracking fishing activity in near real-time through public maps. The integration of these technologies with coordinated police action and effective prosecution may be very powerful.

2.2.4. Marine Spatial Consideration

The optimization of marine resources usage can be achieved through the space allocation, which involves changing traditional spatial links between human beings and ecosystems [9]. Specific ecological, economic, and social conditions determine the ecological environmental footprints and alternatives (region, type, economy, and impact) [10] and IOM implementation. Therefore, it is necessary to address the ecosystems causality and regional interactions, that is, the efforts to match political boundaries and jurisdiction to ecological scales [28], e.g., addressing off-site externalities such as the impact of upstream water on downstream water use. Effective marine spatial planning is ecosystem-based and balanced between the ecological, economic, social, and sustainable development goals. It is strategic and focused on long-term development. Moreover, stakeholders actively participate in the spatial planning process to promote cross-department, cross-organization, and cross-hierarchy integration.

Marine space consideration aims to establish a development framework that minimizes sectoral conflicts by identifying ocean space that is suitable for different uses and activities. It makes use of the sea consistent with marine functions to enable communications between the marine eco-environment and social economy. Marine ecosystems are included in the social and economic cycle, and social economy is also included in the marine ecological cycle, which is beneficial in promoting the benign interaction between the two systems [9]. Consequently, MSP is gaining recognition as a practical way of establishing a more rational use of space and the associated interactions, to balance development with marine ecosystem protection, and to achieve social and economic objectives in a transparent and organized manner. Marine space consideration helps address how to integrate the social, economic, and environmental values in space and address connectivity across domains [9], the two focal issues in implementing IOM.

2.3. Practical Support for the Framework

The practice of ocean governance shows that there is a long process that needs to occur before there is an obvious effect, and the existing successful cases are not abundant. The governance of the Barents Sea in Norway is one of the few successful cases, which provides a good reference. The development of offshore oil and gas resources in the Barents Sea conflicts with traditional industries, such as fisheries, sea transportation, tourism, the sea environment, etc. To exploit offshore oil and gas resources, under the direction of the Norway Government, all the stakeholders including the coastal fishermen, oil and gas exploration companies, and the sea transportation industry, negotiated for the solution for a long time. Finally, the government redefined the shipping routes, offshore oil and gas exploration areas, and fishing operation areas in the sea area [29]. Furthermore, the oil and gas exploration companies compensate the fishermen every year for the loss of fishing due to oil and gas exploration. At the same time, the companies pay ecological compensation to the government for the treatment of ecological damage and environmental pollution [4,29]. In fact, the governance process of the Barents Sea is resolving the conflict between shipping companies’ navigation rights, fishermen’s fishing rights, and oil companies’ oil exploration rights. The division of shipping routes, fishing areas, and oil and gas exploration zones solves the conflict and friction among different stakeholders, and the amount of compensation is determined through a long-term negotiation in operation, which is a process of searching the market equilibrium price.

The Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDL) of Chesapeake Bay in the United States is also a recognized success story. Since 1890, Chesapeake Bay has experienced an exploration process, from traditional governance to EBM governance [30]. The protection and restoration of the bay is coordinated by the Chesapeake Bay Program, part of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The EPA, as the leader of bay governance (Chesapeake Bay is a special case in the administrative system of the United States), determined TMDL through rigorous modeling techniques and established the governance process schedule: Emissions of N (Inorganic Nitrogen), P, and sediment pollution will be fully restored to ideal conditions by 2025 [31]. At the same time, the EPA develops short-, medium-, and long-term plans for the TMDL and tests, and monitors and evaluates state implementation through monitoring facilities. To enable the TMDL to proceed, the EPA has developed state Watershed Implementation Plans (WIPs) with a 2-year evaluation period. If some states make the cuts to the EPA, they will be offered technical and financial support to incentivize them to take aggressive action. Under the EPA, a coordination committee was set up to coordinate the relationship between stakeholders, and an implementation committee was set up to take charge of the implementation of the plan, which was decomposed and implemented to each enterprise in each state [30,31,32]. Unlike Norway, the success of the Chesapeake Bay is due to the guidance of the scientific knowledge (mainly EBM and modeling technique), but also due to the strict institutional design and departmental setup. This shows the importance of EBM and management support.

The successful cases are basically in line with the framework constructed in this study, but they have different emphases and different effects, which show that the framework is reasonable from the perspective of practice. Next, we will study the governance of the Bohai Sea in China with it.

3. Case Study: China’s Marine Management of the Bohai Sea

3.1. IOM for SDG14 in China

China’s marine economy began relatively late compared with that of other nations, with comprehensive marine management only recently undertaken. In the 1990s, the concept of sea–land economic integration was put forward for the first time for marine development and protection planning to guide the marine economy and coastal areas. The concept encompasses simultaneous planning for marine development, terrestrial economic development, and marine eco-environment governance [23]. However, the sea and land economic integration did not completely alter the dual system. Under the development concept that the sea should serve the land economy development, it was proposed that the land and sea system could achieve a more effective allocation of land and sea resources through unified planning, joint development, and comprehensive management [33]. After 2000, the “Scientific Outlook on Development” guided the national development, and the overall planning of land and sea was given importance in coastal provinces and cities; marine industries, infrastructure construction, eco-environment management, and the allocation of production factors became important issues [23]. The issue of marine ecology and the environment has since been added to the agenda, and marine sustainable development issues have been recognized by political and social circles. In 2007, China started “Ecological Civilization” and “Marine Ecological Civilization” (new concepts of development) [34,35]. The eighth Strategic Forum on Maritime Powers suggested that it was necessary to promote marine economy transformation to achieve the coordinated development of the regional economy, society, and marine ecology, under the premise of building a marine ecological civilization to promote the harmonious co-existence between humans and the sea, a virtuous cycle, and sustainable development [36]. Green development of the marine economy and land economy adjustment have since become the most important issues in national marine development. Simultaneously, China has been promoting the institutional reform for ecological conservation, in addition to the political system and mechanisms reform, and an all-round institutional restructuring of it. This is a complex project with sustainable development at its core.

3.2. Selected Case for Analysis

Comprehensive management of the Bohai Sea was initiated in 2000, and it was centered around marine ecological and environmental management. In 2008, a major revision was made to form the Bohai Sea comprehensive management action, which combines the ecological and environmental governance with marine and coastal economic development. Since 2012, coordinated regional development and marine ecological progress have been integrated into this process. The administrative system reform for marine management has begun, and the management system has been regularly innovated, which was revised again to issue the Final Action Plan for the Bohai Sea (FAPBS). It is an overall plan for the Bohai Sea governance at the national level, and mainly sets out the final goals to be achieved and provides some guidelines for governance:

“(1) Through the three-year (2018–2020) comprehensive treatment, the inflow of land-source pollutants shall be greatly reduced, and the inferior Class V water bodies of rivers entering the sea shall be significantly reduced; (2) To ensure steady discharge of pollution sources from industrial direct discharge to the sea; (3) Completing the cleaning up of illegal and unreasonably installed sewage outlets (hereinafter referred to as the two types of sewage outlets); (4) Build and improve the port, ship, aquaculture activities and garbage pollution control system; (5) We will implement the strictest control over reclamation, continue to improve the ecological functions of coastal zones, and gradually restore fishery resources. (6) We will strengthen and improve our capacity for monitoring, early warning, and emergency response to environmental risks. (7) By 2020, about 73 percent of coastal waters in the Bohai Sea will have good water quality (Grade I or II water quality).”[37]

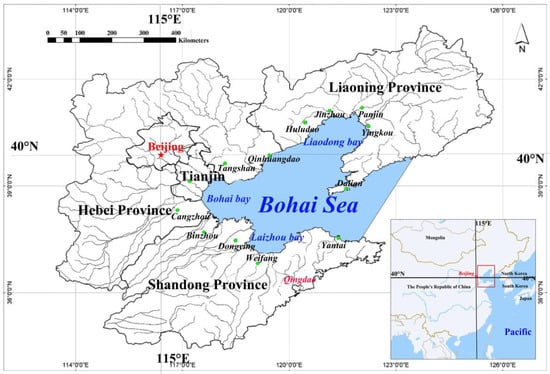

To promote the implementation of the FAPBS, the relevant departments of the State Council (SC) and the governments of the four coastal provinces formed an organization and coordination department. Furthermore, by the FAPBS, the provincial and municipal governments have defined the goals to be achieved in their regions and formulated corresponding plans. The IOM of the Bohai Sea for achieving SDG14 has gradually taken shape through this process. Figure 1 is the Map of Bohai Sea. Figure 1 shows a map of the Bohai Sea, displaying the Bohai Sea area and surrounding provinces.

Figure 1.

Map of Bohai Sea. Note: Taking the line between the coastline junction of Dalian and Dandong on The Liaodong Peninsula, and Yantai and Weihai on the Shandong Peninsula as the boundary, the sea area to the west is the studied area, with 95,000 km2.

The Bohai Economic Zone (including Shandong province, Hebei Province, Liaoning Province, Tianjin City), the Yangtze River Delta economic zone, and the Pearl River Delta economic zone constitute China’s three major marine economic zones. According to government statistics, the total marine industry output value reached 2.27 trillion yuan (330 billion US dollars) in 2016, accounting for 32.5% of the national marine industry’s total output. In addition, such developments discharge a large number of pollutants into the sea. For example, oil exploitation, and marine aquaculture and ecology are destroyed [38] in the process of coastal development and shipping. Consequently, the Bohai Sea’s eco-environment showed prominent signs of deterioration at the end of the 20th century, with studies suggesting that the Bohai Sea would become a lifeless “Dead Sea” [39,40] without intervention. Notably, this is an additional reason for the Bohai Sea Action originating from marine eco-environmental management.

4. Research Strategy for Analyzing the Bohai Sea IOM

Content analysis and semi-structured interviews were conducted to examine the Bohai Sea’s IOM. Interviewees included government officials from the SC, the governances of coastal provinces and cities, in addition to researchers from institutes under the Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China (MNR) and universities. Between October 2019 and March 2023, national and local pilot policy documents on coastal and marine governance, including legislation, administrative regulations, statements, project reports, and technical guidelines and standards were collected from major official websites of the SC, the MNR (including the original State Oceanic Administration (SOA), which was merged into the MNR in 2018, and the contents of the original SOA website can be found on the MNR website), and the Ministry of Agriculture (MA). Data on local pilots and initiatives were obtained from newspapers and provincial and municipal websites to reveal more details about the IOM operations. Local governments in China carry out their work under the leadership of the SC and CPC. In response to the SC and the Communist Party of China (CPC), most of the action strategies and policies of all provinces of the Bohai Sea are consistent.

We interviewed ten stakeholders to gain insights into the idea behind the framework and application of the IOM. Interviews were based either on their positions in government agencies, expertise in coastal and marine management, or view of the processes, outcomes, trends, and recommendations for environmental strategies. Semi-structured interview guidance questions follow the analytical framework in Section 2.2.

5. Results: IOM of the Bohai Sea for SDG14

During the interview, an expert from the MNR said, “In recent years, after many detours, the Bohai Sea eco-environment management has just made some achievements due to the guidance of sustainable development, which is also the practice of sustainable development in China.” The Bohai Sea IOM is a top-down process under the leadership of the CPC, in which the SC formulates macro-planning and local governments formulate the local implementation plans in accordance with the spirit of the CPC, planning of the SC, and local character. The IOM of the Bohai Sea is explained in this section as follows.

5.1. IOM of the Bohai Sea

5.1.1. Ecosystem-Based

The Bohai Sea IOM originated from the environment and ecosystem restoration, subsequently extended to marine resource development and marine economy, and coastal development, and lastly formed an integrated ocean management system.

(1) Marine environment. The marine eco-environment has been central to the Bohai Sea’s IOM as the earliest and most important concern. The SC supports local governments with annual transfer payments to implement the Blue Bay Initiative—marine ecological and environmental restoration. Foremost, this encompasses the control of land-based sources of pollution. The pollution treatment of rivers such as the Liaohe river and Haihe river are some of the first pilot projects initiated in China, after which the “River Chief System” was applied to all rivers entering the Bohai Sea. The main pollution sources include agricultural non-point source pollution, industrial pollution, and urban household pollutant discharge. Projects such as emitters rectification, coastal industry transformation, and domestic garbage disposal projects, are examples of the primary approaches used for pollution control.

In marine industry development, the secondary approaches applied to control pollution include shutting down unqualified oil wells, controlling waste discharge created during petroleum exploitation and mariculture processes, and promoting ecological aquaculture. In addition, mobile pollution sources and their operations (such as the discharge of oil pollutants from shipping vessels and fishing vessels) are under monitoring and restriction for pollution control. Ships with substandard pollutant discharge shall be eliminated, facilities for the reception and treatment of water pollutants of ships built at ports, and vessels disassembled on the water. In addition, monitoring facilities are under construction to improve the ability to control the marine ecological and environmental conditions in real-time.

(2) Ecosystem management. In the Bohai Sea, ecosystem management is mainly conducted around coastal zone estuarine and bay ecosystems. For coastal ecosystem management and protection, local governments have dissolved ongoing illegal reclamation projects in the Red Line areas (the boundary demarcated for marine ecological protection is also the boundary limiting human productive activities), and reclamation projects that do not implement the National Strategy are strictly prohibited. Furthermore, they have accelerated the comprehensive restoration of shorelines and beaches, removed illegal buildings and facilities on both sides of the shoreline, and restored and expanded the coastal forest belts. Through the shoreline restoration project (including coastal erosion protection, the reclamation and restoration of beaches, the demolition of artificial facilities, the implementation of coastal protection, and vegetation sand fixation and restoration projects), the natural coastal form and ecological function can be restored, the shoreline balance maintained, and the length of the natural shoreline restored.

For estuarine bay ecosystem management, actions such as ecological restoration of river estuaries entering the sea, coastal wetlands and afforestation, and the implementation of graded coastal wetlands protections have been taken. Coastal governments have demarcated areas encompassing important wetlands and established natural protection sites for all coast wetland types, such as the Luannan and Huanghua Wetlands in Hebei, Dagang and Hangu Wetlands in Tianjin, and Laizhou Bay Wetland in Shandong. Furthermore, the Marine Nature Reserve, Ecological Demonstration Zone, and Marine Life Conservation District have been established to restore the green coast and its ecological landscape. For example, according to the government statistics, the area of coastal wetland restoration in Tianjin reached 531.87 hectares, and 4.78 km of shoreline were restored from 2018 to 2021.

(3) Marine resources. The use and management of marine resources, such as sea sand, island waters, fishery resources, offshore oil, and strengthening shorelines, have been coordinated to improve their utilization. The status quo is maintained for uninhabited islands, and the illegal exploitation of sea sand has been prohibited.

For the conservation of marine bio-resources, the fishing season, number of fishing vessels, and minimum diameter of fishing nets are regulated to mitigate the fishing capacity and intensity, in addition to promoting the recovery of fishery resources. The Bohai sea management draws on the experience of the TMDL in Chesapeake Bay of the United States, which has yielded good results [32]. Under this system, a marine sanctuary will be established wherein a summer fishing moratorium system shall be strictly implemented and adjusted following investigation and assessment. Furthermore, the fishing operation structure will be gradually optimized, and illegal fishing gear such as no life nets (fishing net with over-dense mesh) and three-no fishing vessels (no valid inspection certificate, registration certificate, or fishing license) shall be banned. Coastal governments are strengthening the ecological aquaculture and landscape layout, promoting pelagic aquaculture and marine ranch construction, and developing marine recreational crop rotation. Baited mariculture is prohibited in ecologically sensitive and fragile seas, severely polluted areas, and areas with a high incidence of red tides. In addition, marine bio-resource conservation is promoted and the establishment of marine ranching demonstration zones supplemented by artificial reefs, bottom seeding, and proliferation is encouraged. One is to control the catch. According to the Tianjin municipal government statistics, the total output of Marine fishing in Tianjin in 2021 decreased by 25% compared with that in 2015. The other is to increase the reproductive capacity. Every coastal city organizes fishery release activities every year. According to government statistics, the four provinces (Shandong, Hebei, Tianjin, and Liaoning) of the Bohai Sea held conservation and release activities (e.g., releasing fry into the sea) at least 300 times in 2020 to promote the proliferation of 4.5 billion units of marine economic species. According to the Tianjin municipal government statistics, nearly 7.2 billion units of various types of seedlings, such as penaeus chinensis, racetus triton, half-smooth tongue sole, Songjiang bass, Talong hexanetus, Scorpenus Xu, and jellyfish, were proliferated and released into the Bohai Sea from 2018 to 2021 in Tianjin City.

(4) Details from small cases. The Liaohe River used to be the most important land source pollution into the Bohai Sea. Before the IOM, more than 20% of the water going into the sea was worse than G(V). In 2008, the Liaoning Provincial government set up the Li Protection Zone, which mainly covers the main river channel and the estuary wetland (1869.2 km2), and set up the Protection Zone Administration to take charge of the river management. Since the “River Chief System” was put into effect in 2011, a series of comprehensive river management measures have been implemented.

The first was the river cleaning work: the river sand mining, planting, and other production activities all stopped, and the river houses and other buildings were all dismantled and relocated. By the end of 2020, in the Liaohe flood protection area, a total of 183 km of embankments were cleared, 284 illegal structures were demolished, 18.7 km2 of trees obstructing the water were removed, and 187 households were relocated. The second one was to delineate and construct a river ecological zone, restore species diversity, and restore the ecosystem. A total of 426.7 km2 of tidal land in the main flood protection area has been delimited to return farmland (forest) to rivers and be naturally fenced. The comprehensive improvement of flood control projects has been strengthened at key points along the route, ecological landscapes in urban areas have been built, and beach land strip parks have been built.

By the end of 2019, the vegetation coverage rate of the riverfront zone remained above 82%, and the ecological landscape of key node projects was significantly improved. The river and lake environment was significantly improved, and more than 45 species of fish, five species of amphibians and reptiles, 83 species of birds, and 242 species of plants have been recovered.

5.1.2. Marketization

Economic interest is fundamental for most coastal stakeholders; however, it is difficult to gain the support of local governments without development. To arouse the initiative of economic subjects, we must follow market law, that is, the law of value of the allocation of marine resources. An expert from the Ocean University of China revealed, “In the early management of the Bohai Sea, eco-environment-centered governance was a plan to let coastal provinces take the initiative to draw blood, and the financial subsidies from SC were not enough to arouse the enthusiasm of locals for blood transfusion. The problem of excluding marine eco-environment from the blood circulation system must be solved, and the root causes of marine eco-environment must be solved in the social and economic system”. That is, marine eco-environment governance should be embedded into the process of marine exploitation and marine economic development, and the role of economic laws in resource allocation should be brought into the social and economic system, while the government should focus on the market failures after products such as marine resource exploitation rights and pollution rights with special permits are introduced.

(1) Macroeconomic environment. A major revision to the Bohai Sea management in 2010 gave rise to the IOM considering the eco-environmental management and regional social and economic construction, which has since become a sustainable development plan involving land and sea [41,42,43,44]. Local governments have seen opportunities within the marine economy and coastal society. Marine industrial clusters, such as deep-sea aquaculture, marine biomedicine, marine engineering construction, marine ecological and environmental protection, marine cultural tourism, and marine transport and logistics have originated from this. Traditional industries, such as marine food processing, marine equipment manufacturing, and marine chemical industries have also grown. In addition, ports, coastal development zones, and coastal towns are also under construction.

For example, the Coastal Town Belt Plan [45] was issued in 2018 to develop a coastal social economy based on adapting to the marine ecosystem. The layout of four coastal cities (including 13 municipal districts) and eight counties/county-level cities around the Bohai Sea have been rearranged [46]. The Hebei province has also planned the layout of a port and the coastal economic zone, such as the Caofeidian Port in Tangshan and Binhai New District of Tangshan and Cangzhou. All projects related to the eco-environment of the Bohai Sea have been subsidized by the SC.

(2) Microeconomic market. The premise for marine resources and the eco-environment to enter the social and economic cycle is to commercialize the sea; however, the most fundamental problem is changing the attributes of marine resources for use as public products.

One solution is to endow the sea with property rights, which can encourage and make full use of the marine resources to enhance their socioeconomic value [47,48]. After the “Notice on the full implementation of market-based selling of the right to use marine exploitation areas” issued in 2012 [29], regulations on the right to use the sea, relevant islands, coastline, and beaches have been gradually expanded and improved to include the transfer of rights through bid invitation and auction, among others [47]. Thus, users (such as fishermen and companies) set a price they are willing to pay for access to the sea and are permitted exclusive use of natural resources in a specified space for a given time. Such efforts have created a market in China that limits the use of marine resources, thereby increasing the competition and scarcity of access, such as sea sand resources, fisheries, and coastal engineering construction spaces.

Market regulation operation failure is a main cause of the limited green development of the coastal economy and industrial transformation, which can only be solved by increasing the responsibilities and enthusiasm of marine resources users (including stakeholders) for ecological and environmental protection. Solutions adopted in the Bohai Sea management include payment mechanisms such as marine ecological compensation, fishery restoration subsidies, and occupation compensation balance. Additional means include transfer payments, tax incentives, fines, and other regulatory methods through subsidies, tax credits, and other means.

Marine ecological compensation requires marine users to pay for ecological losses caused by their activities (such as pollution, wetland damage, and loss of species) to compensate aquaculture farmers and coastal communities [49,50]. Fishery restoration subsidies are payments made by the government to the private sector to support habitat restoration, build artificial reefs and promote fish stocks [51,52], thereby promoting sustainable use of fishery resources to meet seafood demands, internalizing positive externalities, limiting polluting enterprises by the discharge and sewage fines, and closing down or suspending business licenses [53].

5.1.3. Management Support

In the process of the Comprehensive Management of the Bohai Sea, the SC, and local government administrative units have been adjusted, gradually forming an efficient management system. As a unitary country, government actions at all levels are the response to the CPS’s development goals and implementation. For example, the “Action Plan for the Blue Sea in the Bohai Sea” was formulated under the guidance of the Scientific Outlook on Development.

(1) Institutions and management mechanism. The Law on the Protection of Marine Ecology and Environment, The Law on the Use and Administration of Sea Areas, the Measures for the Planning and Administration of Regional Construction use of Sea Areas, the Regulations on the Administration of The Protection and Utilization of Coastal Zones, and measures for the disposal of idle sea areas constitute a relatively complete and formal legal system. This system provides a legal basis for local governments to scientifically and effectively allocate marine resources and develop the marine economy through coastal industries, tourism and leisure, ports and towns, and eco-environment protection [54,55]. To implement the Bay Chief system, the MNR (Ministry of National Resources of the People’s Republic of China, including the original SOA) and National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) have issued a series of guidance documents, such as the Program for Regional Cooperation and Development in the Bohai Rim, to guide local governments in the Bohai Sea management. This has allowed local governments to incorporate marine economic development and eco-environmental governance into their five-year regional development plans or formulated separate action plans, such as local measures for coastal waters and regulations.

(2) Administrative Restructuring. An expert at the MNR (original SOA) said, “Eco-environment governance is key to achieving IOM of the Bohai Sea in China.”

First, the eco-environmental protection system solves problems such as insufficient attention to the eco-environment and inadequate implementation of policies, and insufficient punishment and enforcement [34]. The chief responsibility system strengthens the marine ecological consciousness of leading cadres. The Measures for Accountability for Ecological and the Environmental Damage of Party and Government Leading Cadres directly link the ecology, resources, and the environment to the achievements in leading cadres’ official careers and form the basis for promotion, appointment, and suspension. Lifelong accountability for ecological and environmental damage is implemented. In the selection and appointment of local leading cadres, the resource consumption, environmental protection, and ecological benefits are important factors for assessment and evaluation. Cadres responsible for serious damage to the eco-environment and resources are not promoted to important posts [34]. The “Bay Chief System” is a successful representation of grassroots governance system innovation. The coastal gulf of the Bohai Sea is assigned to the top leaders of the party or government, and the eco-environment of the Gulf becomes a rejection index for cadre appointment and suspension [56], which establishes the priority status of the Bohai Sea in government policies.

Second, as part of administrative restructuring since 2016, the former dual leadership comprised of superior competent departments was changed to a vertical leadership of provincial governments [57]. County environmental departments are now municipal environmental departments that are no longer under the jurisdiction of county governments that can uniformly exercise the power of supervision and inspection over municipal departments and their dispatched agencies (formerly county-level environmental protection departments), and serve as undivided enforcement units. Consequently, grassroots environmental protection work has been freed from the restrictions of local governments, and the final decision-making is transferred to the provincial government, which solves the problem of the environmental department’s ability to control the environment due to local interference.

Third, the departments’ functioning has been adjusted and organized. Before 2018, different aspects of the same ecological or environmental problem were dealt with by different departments, with several leaders but no defined authority. For example, watershed water environmental protection and sewage outlet management was under the department of water resources, agricultural non-point source pollution was under the jurisdiction of the agriculture department, and groundwater pollution was the responsibility of the land department. Sewages from these sources eventually flow into the sea, causing pollution. Although they are the responsibility of the SOA (original), in fact, this policy cannot be implemented as it involves the responsibilities of multiple departments, which is beyond the coordination authority of the SOA (original). However, the situation has since changed due to the Reform of the Plan for Deepening the Reform of Party and State Institutions issued in 2018. All marine resources, such as groundwater, rivers, the gulf, island, sand, and beach are under the jurisdiction of the MNR, and all eco-environmental protection, such as groundwater pollution prevention and agricultural non-point pollution are integrated under the Ministry of Ecological Environment (MEE) to tackle the problem of comprehensive marine management [58]. In addition, provincial governments have made corresponding adjustments to improve the long-standing malpractice of multiple jurisdictions and leadership, which has improved the coordination between land and sea management and the integrity of eco-environmental protection [58].

(3) Knowledge, Marine Database, and Research. The biggest obstacle in marine management is the lack of relevant knowledge. Marine monitoring has always been prioritized in the Bohai Sea management, with the continuous development of encryption monitoring sites, monitoring items, and monitoring frequency. For example, the number of monitoring items, mainly on N (Inorganic nitrogen), NH4, and TP (total phosphorous) has been increased to >30, and biological species monitoring has been introduced. Furthermore, the timing and fixed-point detection has been switched to real-time dynamic detection, and all real-time monitoring data are published on the MEE website, which improves the application scope, reference value, and credibility of the test results.

Under the National Action Plan for Sustainable Development in 2030, China has proposed to build earth databases, including a marine database, which will provide important data for marine development and management [59]. The database will increase transparency for the offshore resource trading platform and make the characteristics of the Object of Transaction (including its ecological surroundings) more comprehensive, enhancing the transaction confidence of the stakeholders, reducing transaction costs, increasing the trading frequency, and promoting the actual transaction price (i.e., the market price can reflect the resource value). An official of the MNR stated, “Human’s knowledge of the sea is far less than that of the land, and the openness of marine projects, including military, transportation, and private commercial information cannot be decided by one agency. The outcome of openness is uncertain. Poor information sharing leads to weak tradability of marine access, which further impedes the determination of optimal trading size, frequency, and price”.

Marine scientific research is expanding rapidly and receiving increasing investment. The number of projects funded by the MNR, the National Natural Science Research Fund, and the Social Science Research Fund for the Marine field has increased. According to the Earth Science Department of the MNR, 2397 applications (up from less than 200 in 2001) were accepted in the marine and polar fields in 2021, with an increase in 45 percent since 2017, indicating a significant increase in the number of scientific research talents in the marine field. On the other hand, according to the public data of the Ocean University of China (OUC), more than 200 projects were funded by the MNR for the first time in 2022, with a funding amount of nearly 200 million yuan (about 29 million US dollars). Most of these projects are related to the ocean, which shows the increasing funding for marine scientific research. Several projects are focusing on high-sea scientific research, aquaculture, and pollutant digestion in marine water, and studies on the inter-basin water management and sea–land coordinated management have attracted much attention in the field of social sciences. Furthermore, coastal regions are supporting the construction and expansion of universities, colleges, and research institutes to study the oceans. For example, the OUC, Shandong Province, and the Institute of Marine Biology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences jointly established the National Oceanographic Laboratory to study the frontiers of the ocean.

5.1.4. Spatial Consideration

An expert from the OUC explained, “China’s Marine Functional Zones are spatial distinctions between the ecological and operational properties of sea areas.” Thus, ecological attributes and socioeconomic characteristics are arguably the prerequisites for achieving the IOM. From the perspective of the market economy, the ocean’s economic value and ecological cost are the basis of ocean utilization models.

(1) Marine Function Zoning. The space of the Bohai Sea encompasses the sea area, coastline, and island, which are accordingly divided by The National Marine Function Zoning of China based on the carrying capacity, development intensity, and potential of the marine eco-environment to provide information on the following three functions: industrial town construction, agricultural and fishery production activities, and ecological and environmental services. Based on these main functions, it is further divided into the following four categories: the optimized development zone, key development zone, restricted development zone, and prohibited development zone, laying the foundation for the use of sea areas, development of marine resources, and its protection [60,61,62,63]. Consequently, the principles of optimal development and regional priorities of the waters in the Liaodong and Shandong Peninsulas, and the Bohai Bay have been clarified, and Shandong, Hebei, Tianjin, and Liaoning have completed both the local and main marine function zoning.

As a supplement to the Marine Function Zoning, China has implemented the Marine Ecological Red Line Districts System, which forms the basis for defining the eco-environment. Ecologically fragile marine ecosystems with functional importance are designated as key control zones [64] and marine protected areas, including important coastal wetlands, important estuaries, islands under special protection, and sea areas protected by sand sources, important sandy shorelines, natural landscapes, cultural historical sites, important tourist areas, and important fishing areas and have been designated as the Red Line Districts. Based on ecological characteristics and practices, they are further divided into prohibited and restricted development zones to facilitate the classification and control of marine resources, which is of great practical significance for maintaining marine ecological security and ensuring socioeconomic development.

(2) Coastal Towns and Cities. The planning of coastal towns and industrial clusters has been enabled by the refinement and implementation of Marine Function Zoning, and the rational distribution of production and housing. For example, the Hebei Province proposed a pattern for marine development, marine ecological security, and marine aquatic product security. The marine development pattern refers to the modern comprehensive port cluster (Qinhuangdao port, Tangshan port, and Huanghua port), and coastal industrial area (Shanhaiguan, Laoting, Caofeidian, Fengnan, and Bohai New Area); the marine ecological security pattern refers to the islands, natural shorelines, coastal landscape belts, important estuaries, and important coastal wetlands; the pattern of marine aquatic product security refers to the traditional fishing grounds, mariculture area, and aquatic germplasm resources protection area.

(3) River and Bay Zoning. The “River Chief System” and the “Bay Chief System” come under marine space management and are related to cross-basin governance and land–sea coordination. Both systems are based on the river eco-environment and bay eco-environment, which break the original administrative division and promote the cross-regional integration of resources [56,65]. The Liaodong bay, Bohai bay, and Laizhou bay are the three largest bays in the Bohai sea, while the Liaohe River, Haihe River, and Huanghe River are the three largest rivers flowering into the Bohai sea, all of which are located across different administrative regions; thus, governance is difficult. The implementation of the “River Chief System” and “Bay Chief System” has largely solved the long-standing problems of cross-basin and sea area cooperative governance, and the cross-regional allocation of resources.

(4) Details from small cases. Marine ecological reserves have become the bottom line of MSP, and the utilization of ecological resources has become one of the goals of many regions. Yantai is a city in the Shandong Province located to the east of the Bohai Sea. In 2022, The Yantai Government issued a new MSP, namely, Marine spatial planning of the Yantai Huanghai Sea and Bohai sea New Area [66]. The new MSP, to a large extent, focuses on the marine eco-environment and integrates the harbor industries and sea area use in the seven bays under its jurisdiction from the perspective of space. Tourism, fishery, and other industries with high eco-environmental requirements have been explored. Industries such as marine chemistry, which were damaging to the environment and ecology, were reintegrated. For example, the new MSP emphasizes the development of modern ecological fishery and aquaculture, and some industries move away to create conditions for ecological aquaculture. In addition, the plan combines the original marine ecological reserve with tourism to realize the combination of protection and development. This is actually the process of realizing the value of marine ecological resources with the help of MSP and combining economic development with marine protection through the design and institutional support of the government.

According to the government data, after the implementation of the new MSP in 2025, it is expected that the tourism industry will receive 140 million tourists and achieve a total tourism revenue of over 180 billion yuan (26,132.8 million US dollars); the annual breeding capacity of aquatic seedlings in the city will reach 360 billion units, the total output of aquatic products will be maintained at 1.6 million tons, and the construction area of marine ranches will reach 1333.3 km2 [67,68]. Yantai solves the contradiction between marine ecosystem and environment management and economic and social development through the MSP, which injects vitality into urban development.

5.2. Achievement and Problems of IOM of the Bohai Sea for SDG14

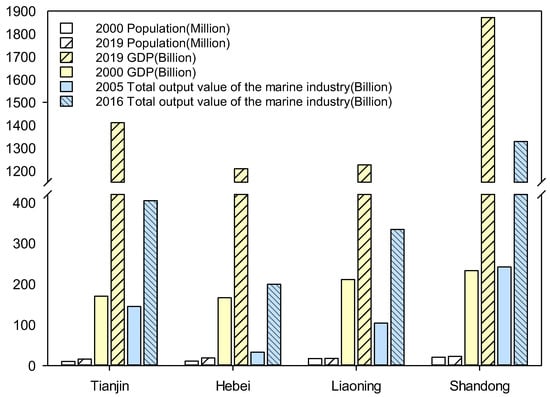

The Bohai Rim Economic Zone’s remarkable achievements in the socioeconomic development of the last 20 years are shown in Figure 2. The Bohai Sea’s coastal area has achieved unprecedented economic development, way faster than that of the national average. Social and economic data of 13 prefecture-level cities in the Bohai Rim region show that the total marine output value of 13 cities in 2019 was 5716.96 billion yuan (750 billion US dollars), 7.3 times (780.27 billion yuan) that of 2000; in 2016, the total marine output value was 226.57 billion yuan (33 billion US dollars), 4.3 times (522.85 billion yuan) that of 2005. When examining the marine output values between regions, the marine industry development in the coastal provinces of the Bohai Sea markedly is uneven. In 2016, the marine output value of Shandong accounted for more than half of that of the whole region, reaching 1.33 trillion yuan (5.5 times that of 2005), while the marine output value of the Hebei province was at a minimum of 241.8 billion yuan (35 billion US dollars).

Figure 2.

Achievements in socioeconomic development based on the Bohai sea’s IOM.

In addition, the social situation in the Bohai Rim Economic Zone has improved with the population growth. The total resident population of the 13 coastal cities increased from 58.35 million in 2000 to 74.34 million in 2019, an increase in 16 million (average annual growth rate of 1.28%). Hebei and Tianjin showed the most growth, while Liaoning showed the least. This may be due to the overall slow development of Northeast China in the last decade, in which the population has been in a state of outflow.

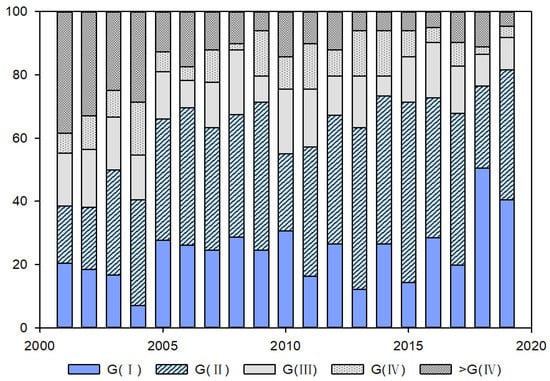

Bohai Sea management has gained eco-environmental achievements, such as reversing eco-environmental deterioration (Figure 3). Herein, the marine water quality has improved, the total proportion of G(I) and G(II) water quality has increased, and the seawater quality is optimal. However, the total proportion of G(I) has been maintained at 20%, indicating that seawater pollution persists.

Figure 3.

Results of seawater quality assessment of the Bohai sea (2001–2019).

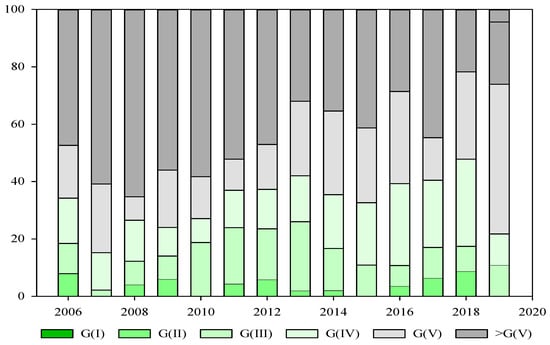

The quality of the water flowing into the sea from rivers has been well controlled with remarkable success (Figure 4). In particular, G(II), G(III), G(IV) proportion in river total water quality has shown improvement since 2010. The proportion of the water quality superior to G(IV) has increased, whereas the proportion of G(V) and water quality inferior to G(V) have decreased. Notably, the proportion of water quality > G(V) has decreased substantially. However, there is still no G(I) water quality in the rivers, and the total proportion of G(II) and G(III) for water quality has been maintained at ~20%, whereas that of G(V) has shown a negligible decrease.

Figure 4.

Quality assessment results of river water flowing into the Bohai Sea (2006–2019).

6. Reflection and Discussion

6.1. Advantages of the Chinese Governance of the Bohai Sea

This study provides a detailed understanding of the IOM application in the management of the Bohai Sea through an analytical framework containing four aspects. Our results highlight the importance of the IOM of the Bohai Sea for achieving SDG14 and the advantages of the IOM in China. The IOM promotes the coordination of social, economic, and marine ecology at the macro level, and maintains marine ecological balance at the micro level, such as improving the allocation efficiency of resources, reducing the transaction cost, and improving the participation enthusiasm of stakeholders.

First, marine exploitation and marine eco-environmental governance integrate with the socioeconomic system through marketization (such as the assessment of resources and ecological loss). This illustrates an approach to the assessment of ecosystem services bundles that is consistent with the spatial relevance of marine ecosystem functions, thereby maximizing social benefits [69]. In addition, the marine ecological and environmental service integration in social and economic development can increase beneficiaries and avoid the exclusivity of other services caused by service commercialization [70].

Second, market-oriented rules help to maintain the natural capital and eco-environment integrity in the evaluation scheme. The evaluation scheme, transaction mode, and pricing mechanism of ecological resources (such as bidding and the basic price of ecological compensation) enable marine resources to enter the market, making the value of natural capital more clearly understood and accepted by society. The government can protect marine resources and the marine eco-environment by controlling the transaction threshold and transaction rules. Property rules and liability rules are beneficial for overcoming the externality of public resources and reducing the transaction costs [71]. Considering the non-exclusivity of many coastal and marine environments, governments must limit the right to use resources through protection liability in the form of licenses or legal provisions. Compared with the Barents Sea, the market price discovery of ecological and environmental resources in the Bohai Sea is more efficient. For example, it has taken years of discussion and demonstration for the Barents Sea oil and gas producers to implement the ecological compensation scheme [72], but the Bohai Sea’s ecological compensation scheme is simpler to implement. In 2021, for example, a city in Liaoning province sold 50 million tons of sea sand mining rights through an open bidding process that took less than six months.

Third, regulations and administrative rules create surroundings for defining and advancing the cross-sectoral, long-term, ocean-related goals [2]. The ocean-related laws and the specialized regulation of the Bohai Sea form a system that makes the IOM flexible, holistic, and adaptive. The government institution, system reform, and the efficiency of ecological and environmental management have greatly improved. There are many similarities between the Bohai Sea and that of the Chesapeake Bay in the United States, such as the top-down coordination role played by the government. However, the difference is that the United States has a permanent organization while China does not set up a separate department. It only establishes a coordination relationship between relevant departments and local governments. China’s Bohai institutional structure is based on national institutional reform, which has a strong relationship with China’s one-party dictatorship and political system. However, as for the federalist countries, in the absence of permanent institutions, the independence of the states and the complexity of the multi-party relationship make it difficult for the ruling party and the central government to unify all the forces in one direction [73]. Furthermore, an integrated administrative structure has played an important role in the efficiency of China’s IOM, which may be difficult to adopt in federalist countries such as the United States.

6.2. Shortcomings of the Chinese Governance of the Bohai Sea

First, the IOM in China has not achieved complete marine ecosystem and socioeconomic system integration. Resource allocation based on the socioeconomic system might not reflect the marine ecosystem core values, which may not be directly channeled through the price mechanism. In addition, the assessment and spatial planning of the marine eco-environment by administrative means may not reflect the marine value and may hinder the role of the Law of Value. Thus, balancing the administrative intervention between marine ecology and socioeconomic laws becomes problematic.

Second, in the marketization process, the government plays a prominent role in enabling coordination by acting as a regulatory intermediary to establish links between participants. This monopoly situation (that is, centralizing the services or the capital provided by the provider) and the intermediary roles can reduce transaction costs by minimizing the number of participants involved [71]. However, this does not create a favorable market (for example, transparent market prices and an increase in voluntary participation). In some cases, stakeholders’ participation depends on their relationship with the government. In essence, the multiple roles of the government are likely to create political pressure on the functioning of the market. This situation is most marked in the distribution of subordinate power such as financial subsidies and franchise administrative licenses. The efficiency of Bohai’s Marine market value may have been achieved at the expense of stakeholders. Market pricing in China is strongly government-colored. For example, the sale of 50 million tons of sand mining rights in Liaoning in 2021 was in fact strongly government-special-operating-license-colored. Reconciling the interests of the fishermen involved in placer mining may not have been effectively considered. The speed of market price discovery of marine resources has increased, but the effect may be questionable.

Third, the top-down management approach of the Chinese government, although appealing and promising at present, has the characteristics of a political movement in the Bohai Sea IOM [74], lacks the participation of sufficient social subjects, and its long-term effects are uncertain. Furthermore, there is no formal inter-provincial coordination mechanism, especially at the provincial level; however, the Bohai Sea IOM lacks coordination. In solving temporary problems in the Bohai Sea governance, the MNR (including the original SOA) and NDRC have played a coordinating role among others, but no institutional coordination mechanism or organization beyond these departments has been established, as seen in the governance of Chesapeake Bay by the United States.

Fourth, the existing administrative management and space considerations lack a logical foundation. The implementation of ecological compensation and payment for the use of sea areas is under administrative control, and the cause-and-effect relationship between policies and the marine ecological environment system lacks attention. Our results show that there is no specific administrative scale matching the upstream and downstream allocation of resources (such as water) or basin-based causal relationships.

In summary, since coastal and marine areas are largely public resources, and their property rights are owned by the state, the Chinese government implements the IOM by relying heavily on economic incentives supplied by regulatory support and past advantages. Based on the above analysis, suggestions for the improvement of the IOM in the Bohai Sea can be put forward in relation to achieving SDG14.

6.3. Efforts for Improvement

To improve the Bohai Sea IOM, we propose three suggestions. First, the government’s role in the ecosystem and socioeconomic system coordination should be weakened to promote the automatic adjustment of both. A dynamic assessment system of marine resources and ecological value can be established based on the marine eco-environmental monitoring system and marine databases to identify and evaluate the key marine ecosystems in a dynamically and timely manner [75]. The integrated marine management can embody the marine ecological value and enable the marine ecological resources adaptation of the Law of Value, while correcting the information asymmetry, maintaining a lower level of transaction costs, increasing the transaction frequency, and generating optimal pricing for marine services. This will both reduce the pressure of government macro-control and correct for illogical processes in administrative supervision.

Second, regional cooperation requires more attention, with consideration of their potential to address local issues across authorities, overcome sectoral shortages, and promote policy implementation. Therefore, the formation of a management department for the Bohai Sea is necessary to strengthen the inter-ministerial and inter-regional cooperation and normalize communication and coordination. In turn, this will promote the coordination between the central and local governments. The Bohai Basin Management Committee should be established based on the “River Chief System” and “Bay Chief System” for formulating trans-regional water quality. These methods are feasible, as China is focusing on Ecological Civilization construction and administrative reform [57], and the institutional arrangements adopted are jointly pursued by the CPC and SC [34]. According to China’s Administrative Law, the SC can rearrange the responsibilities of relevant ministries, directly approve the provincial government’s proposal to simplify legal procedures, and adjust the arrangement of provincial agencies [59].

Last, stakeholders, involved in ecological and environmental governance in particular, should be encouraged to participate in marine services, enrich marine governance, and weaken the role of the government in the market economy. Furthermore, it is also worthwhile to strengthen social learning and the recognition of payments for coastal and marine resources. Compared with developed countries, there may be room for improvement in China’s Bohai governance to balance more stakeholders. Although the subsidy scheme in the governance of the Barents Sea in Norway is relatively inefficient, the interests of all parties have been taken into account, which provide a good reference. A better atmosphere of partnership and communication should be established to share social, economic, and ecological information for establishing more marketization awareness and support for the IOM [76]. Consequently, compulsory participation can be gradually transformed into voluntary participation with a higher willingness to pay, and thereby benefit the environmental and socioeconomic efficiency of the IOM [77].

7. Conclusions

This study comprehensively examined the application of integrated ocean management (IOM) for the Bohai Sea, China. We discussed four unique characteristics of the IOM framework: the marine ecological environment foundation, market operation support, management support, and space considerations. The management of the Bohai Sea in China shows that this framework has been partly effective in achieving social and economic development and reversing marine eco-environment deterioration. This study attempts to make up for vacuuming the implementation framework of the IOM and establishes a benign meshing relationship between oceans and human beings by using the existing ocean governance approaches and theories. Ecosystem-based management presents the idea of human activities being embedded into the marine eco-environment; marine spatial planning addresses the way in which human activity science is embedded in marine ecosystems; and marketization solves the problem of marine resources being embedding into the social and economic system, that is, the discovery of the market value of resources makes the resources enter the economic cycle. However, all these problems can only be effectively solved under the effective support of the political system, because the goal of bringing the established vicious circle relationship into SDG14 is actually to move from one steady state to another, and the breakthrough of the system threshold needs to be promoted by external forces, that is, to overcome the path dependence requires the role of government intervention. However, Bohai Sea management uses a top-down approach, wherein policies that are largely independent of the market determine the marine service supply, set prices, or negotiate freely between the supply and demand of marine ecological services. The use of coastal and marine policies to address complex interactions between the marine ecosystem and socioeconomic system remains limited owing to the lack of a stable self-operating model. In contrast, the market operation of China’s IOM mainly relies on government incentives.

Further, our findings highlighted the importance of the IOM of the Bohai Sea for achieving the goals of SDG14, by promoting social, economic, and ecological coordination, and ensuring marine ecological balance by optimizing resource allocation efficiency and transaction costs, and encouraging stakeholder participation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.X. and J.Y.; data curation, formal analysis and investigation: Y.X. and D.L.; methodology, software and roles/writing—original draft: Y.X.; funding acquisition, project administration, supervision and writing—review & editing: J.Y.; resources, validation and visualization: J.Y. and H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Philosophy and Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 19CJY023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Definitions of some key terms.

Table A1.

Definitions of some key terms.

| Name | Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Integrated Ocean Management | IOM | Integrated Ocean Management (IOM) is an ecosystem and knowledge-based holistic approach to planning and managing the use of Marine space. Its goal is to balance the various uses and needs to achieve a sustainable marine economy and healthy ecosystems. In addition, IOM has introduced a lot of implementation tools, but there is no clear and fair definition of concepts so far. However, ecosystem-based management and marine spatial planning are its core [2,3]. |

| Market-Based Instruments | MBIs | Market-based instruments (MBIs) is a generic term referring to a range of approaches (e.g., cap and trade schemes, payment schemes, and levies) to address environmental policy issues in an economically efficient way [10]. |

| Ecosystem-Based Management | EBM | Ecosystem-based management (EBM) is an integrated approach to management that considers the entire ecosystem, including humans. The goal of EBM is to maintain an ecosystem in a healthy, productive, and resilient condition so that it can provide the services humans want and need. EBM differs from current approaches that usually focus on a single species, sector, activity, or concern; it considers the cumulative impacts of different sectors [78]. |

| Marine Spatial Planning | MSP | Marine spatial planning (MSP) is used to create geospatial plans that identify what spaces of the ocean are appropriate for different uses and activities. These plans have similarities with sustainable ocean economy plans, which describe how to sustainably use the ocean and its resources to advance economic and social development [31]. |