A Review of Household Food Waste Generation during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What is the quantity and composition of household food waste during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- (2)

- Has there been a change in the quantity and/or composition of household food waste since the onset of the pandemic?

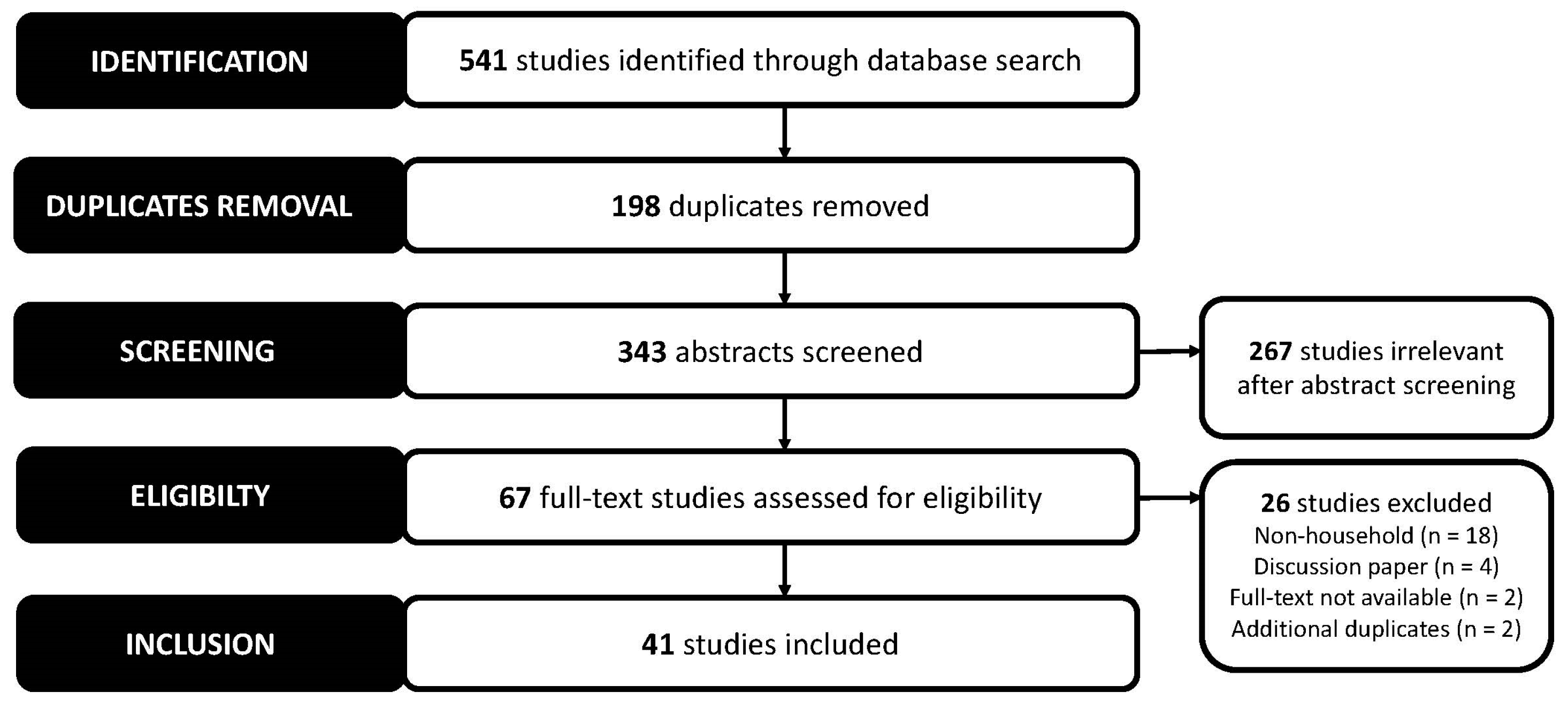

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Direct Measurement Studies

3.2. Studies Using Self-Reported Recall Data

| Study | Geography | Sample Size | Time of Data Collection | Perceived Quantity and Composition of Food Waste | Perceived Changes in Food Waste Quantity and Composition during COVID-19 Compared to before the Outbreak |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [26] | United Kingdom | 473 survey respondents | March 2020 | Avoidable food waste: respondents wasted 9% of purchased waste (i.e., purchased and thrown away uneaten) and 7% of cooked waste (e.g., cooked before being thrown away). The most wasted types of purchased waste were green leafy vegetables, carrots, potatoes, and sliced bread. The least wasted types of purchased waste were beef and chicken. The most wasted types of cooked waste were polenta, green leafy vegetables, and white rice. The least wasted types of cooked waste were beef, chicken, and bread. | Not reported |

| [27] | Mexico | 525 survey respondents | December 2020 to January 2021 | Total food waste: Fruit: 19% wasted Vegetables: 21% wasted Beef, chicken, and pork products: 10% wasted Fish and shellfish: 4% wasted Milk, yogurt, and dairy products: 10% wasted Eggs and cheese: 6% wasted Tortilla, rice, cereals, and pasta: 15% wasted Bread and pizza: 7% wasted Seasonings: 4% wasted Desserts: 5% wasted | Total food waste: −2% ** |

| [28] | Montenegro | 514 survey respondents | May to June 2020 | Avoidable food waste: the most wasted types of food were bread and bakery products, followed by fruit and vegetables. Almost none: 17% of respondents Very little: 38% of respondents Reasonable amount: 27% of respondents More than I should: 11% of respondents Much more: 7% of respondents | Avoidable food waste: Decrease: 5% of respondents No change: 74% of respondents Increase: 21% of respondents |

| [29] | Serbia | 1212 survey respondents | May to June 2020 | Avoidable food waste (kilograms/week): No wasted food: 46% of respondents <0.25: 22% of respondents 0.25 to 0.5: 21% of respondents 0.5 to 1: 7% of respondents 1 to 2: 2% of respondents >2: 1% of respondents | Avoidable food waste: Decrease: 8% of respondents No change: 63% of respondents Increase: 30% of respondents |

| [30] | North Macedonia | 754 survey respondents | May to June 2020 | Avoidable food waste (kilograms/week): No wasted food: 52% of respondents <0.25: 23% of respondents 0.25 to 0.5: 18% of respondents 0.5 to 1: 5% of respondents 1 to 2: 1% of respondents >2: 1% of respondents | Avoidable food waste: Decrease: 5% of respondents No change: 57% of respondents Increase: 38% of respondents |

| [31] | Canada | 8272 survey respondents | August 2020 | Avoidable food waste (kilograms/week): 0: 17% of respondents *** <2: 73% of respondents 2 to 4: 20% of respondents 4 to 6: 6% of respondents 6 to 8: 1% of respondents >8: 1% of respondents | Avoidable food waste (kilograms/week): <2: 80% of respondents 2 to 4: 15% of respondents 4 to 6: 5% of respondents 6 to 8: 1% of respondents >8: 1% of respondents |

| [34] | Spain | 6293 survey respondents | May to June 2020 | Avoidable food waste: 0.09 kg per capita per week | Avoidable food waste: Decrease or no change: 96% of respondents Increase: 3% of respondents Not applicable: 2% of respondents |

| [36] | Gweru City, Zimbabwe | 169 survey respondents | 2021 | Organic waste: 35.2 kg per household per week | Not reported |

| [38] | Turkey | 1098 survey respondents | March to June 2020 | Avoidable food waste: the most wasted types of food were bakery products, leftover foods, and fruit and vegetables. The least wasted types of food were milk and dairy products, beverages, cooking oil and related products, and legumes. | Avoidable food waste: Fresh fruit and vegetables: decrease *** White meat and products: decrease *** Milk and milk products: decrease *** Packaged take-home foods: decrease *** Bread and flour products: decrease *** Legumes: decrease *** Leftover foods: decrease *** |

| [39] | Tunisia | 284 survey respondents | March to April 2020 | Avoidable food waste: the most wasted types of avoidable food were bakery products, vegetables, and fruit. The least wasted types of avoidable food were fish and seafood, meat and meat products, and pulses and oilseeds. | Not reported |

| [40] | Portugal, Italy, Germany, Brazil, Estonia, United States, Australia, Canada, Singapore, United Kingdom, Denmark, Spain, Poland, Finland, Bangladesh, Argentina, Chile, Ireland, New Zealand, Japan, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Vietnam | 204 survey respondents | August to November 2020 | Total food waste: the most wasted types of food were fruit and vegetables, meat, dairy products, bread, and fish and seafood. The least wasted types of food were ready-made meals, canned food, milk, cereal and grain products, and potatoes. | Total food waste: Decrease: 15% of respondents No change: 37% of respondents Increase: 45% of respondents Do not know: 3% of respondents |

| [41] | Peru | 418 survey respondents | May 2020 | Avoidable food waste: vegetables, fruit, and roots and tubers were the most wasted types of food. No wasted food: 63% of respondents Some wasted food: 35% of respondents | Not reported |

| [42] | Poland | 500 survey respondents | March to April 2021 | Total food waste: The most wasted types of food were fruit, vegetables, bread, and dairy products | Not reported |

| [43] | Greece | 2205 survey respondents | April 2020 | Total food waste: The most wasted types of food were dairy products, fruit and vegetables, and cold meat. No wasted food: 22% of respondents | Not reported |

| [44] | India and United States | 590 survey respondents (India = 264, United States = 326) | April to May 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: Increase *** amongst respondents with a higher need for cognitive closure (i.e., the desire for definitive answers without ambiguity) |

| [45] | United States | 946 survey respondents | October 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: Decrease: 51% of respondents *** No change: 23% of respondents Increase: 27% of respondents |

| [46] | China | 2126 survey respondents | April to May 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: Decrease: 40% of respondents No change: Not reported Increase: Not reported |

| [47] | Bogotá, Medellín, Cali, and Barranquilla; Columbia | 579 survey respondents | July 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: Decrease: 55% of respondents No change: 31% of respondents Increase: 14% of respondents |

| [48] | Pakistan (rural) | 963 survey respondents | March 2021 | Not reported | Total food waste: Decrease: 77% of respondents No change: 19% of respondents Increase: 4% of respondents |

| [49] | Italy | 1078 survey respondents | April to May 2020 | Not reported | Avoidable food waste: −37% Bread: −60% Pasta and rice: −44% Meat, fish, and eggs: −50% Milk and dairy products: −51% Vegetables: −49% Fruit: −50% |

| [50] | Italy | 1865 survey respondents | May 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: Decrease: 54% of respondents No change: 43% of respondents Increase: 3% of respondents |

| [51] | Italy | 1500 survey respondents | May 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: Decrease: 52% of respondents No change: 40% of respondents Increase: 8% of respondents |

| [52] | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 3133 survey respondents | October to November 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: Decrease: 0% of respondents No change: 97% of respondents Increase: 3% of respondents |

| [53] | Russia | 1297 survey respondents | October to November 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: Decrease: 15% of respondents No change: 75% of respondents Increase: Not reported |

| [54] | Portugal | 841 survey respondents | May to June 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: Decrease: 36% of respondents No change: 60% of respondents Increase: Not reported |

| [55] | New Zealand | 3028 survey respondents | April to May 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: Decrease: 45% of respondents No change: 55% of respondents Increase: 6% of respondents |

| [56] | New York, United States | 300 survey respondents | August 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: Decrease: 37% of respondents No change: 38% of respondents Increase: 20% of respondents |

| [57] | Qatar | 579 survey respondents | May to June 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: Decrease: 45% of respondents No change: 42% of respondents Increase: Not reported |

| [58] | Italy | 1188 survey respondents | April 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: Decrease: 49% of respondents No change: 45% of respondents Increase: 6% of respondents |

| [59] | Turkey | 511 survey respondents (careless planners and cooks = 90, resourceful planners and cooks = 285, careless planners and resourceful cooks = 136) | January 2021 | Not reported | Total food waste: Decrease: 32% of careless planners and cooks, 31% of resourceful planners and cooks, and 29% of careless planners and resourceful cooks No change: 33% of careless planners and cooks, 26% of resourceful planners and cooks, and 24% of careless planners and resourceful cooks Increase: 13% of careless planners and cooks, 4% of resourceful planners and cooks, and 3% of careless planners and resourceful cooks No wasted food: 21% of careless planners and cooks, 39% of resourceful planners and cooks, and 43% of careless planners and resourceful cooks |

| [60] | United States and Italy | 954 survey respondents (United States = 478, Italy = 476) | April 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: Decrease: 49% of respondents No change/increase: 51% of respondents |

| [61] | United Kingdom | 205 survey respondents | June to July 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: Increased |

| [62] | Bangkok, Thailand | 239 survey respondents | June 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: Decrease: 5% of respondents No change: 19% of respondents Increase: 76% of respondents |

3.3. Studies Using Secondary Data

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U.; Van Otterdijk, R.; Meybeck, A. Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention. 2011. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/014/mb060e/mb060e.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- United Nations Environmental Programme. Food Waste Index Report 2021; United Nations Environmental Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021; Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Cuéllar, A.D.; Webber, M.E. Waste food, wasted energy: The embedded energy in food waste in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorward, L.J. Where are the best opportunities for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the food system (including the food chain)? A comment. Food Policy 2012, 37, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werf, P.; Seabrook, J.A.; Gilliland, J.A. “Reduce food waste, save money”: Testing a novel intervention to reduce household food waste. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 151–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quested, T.E.; Marsh, E.; Stunell, D.; Parry, A.D. Spaghetti soup: The complex world of food waste behaviours. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 79, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Standards Agency [FSA]. COVID-19 Consumer Tracker Waves 1–4. 2020. Available online: https://www.food.gov.uk/research/research-projects/the-covid-19-consumer-research (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- National Zero Waste Council and Love Food Hate Waste Canada [NZWC and LFHWC]. Food Waste in Canadian Homes: A Snapshot of Current Consumer Behaviours and Attitudes. 2020. Available online: https://lovefoodhatewaste.ca/get-inspired/food-waste-in-2020/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- International Food Information Council [IFIC]. Impact on Food Purchasing, Eating Behaviors, and Perceptions of Food Safety. 2020. Available online: https://foodinsight.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/COVID-19-Consumer-Research.April2020.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Waste and Resource Action Programme [WRAP]. Citizen Responses to the COVID-19 Lockdown—Food Purchasing, Management and Waste. 2020. Available online: https://wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Citizen_responses_to_the_Covid-19_lockdown_0.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- International Food Information Council [IFIC]. A Second Look at COVID-19’s Impact on Food Purchasing, Eating Behaviors, and Perceptions of Food Safety. 2020. Available online: https://foodinsight.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/IFIC-COVID-19-May-2020.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- World Health Organization. Timeline of WHO’s Response to COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Khangura, S.; Konnyu, K.; Cushman, R.; Grimshaw, J.; Moher, D. Evidence summaries: The evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst. Rev. 2012, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Werf, P.; Seabrook, J.A.; Gilliland, J.A. Food for naught: Using the theory of planned behaviour to better understand household food wasting behaviour. Can. Geogr. 2019, 63, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, H.; van der Werf, P.; Seabrook, J.A.; Wray, A.; Gilliland, J.A. The quantity and composition of household food waste during the COVID-19 pandemic: A direct measurement study in Canada. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 82, 101110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everitt, H.; van der Werf, P.; Seabrook, J.A.; Gilliland, J.A. The proof is in the pudding: Using a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of a household food waste reduction intervention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laila, A.; von Massow, M.; Bain, M.; Parizeau, K.; Haines, J. Impact of COVID-19 on food waste behaviour of families: Results from household waste composition audits. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 82, 101188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubíčková, L.; Veselá, L.; Kormaňáková, M. Food waste behaviour at the consumer level: Pilot study on Czech private households. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicarelli, V.; Bux, C. Food waste in Italian households during the COVID-19 pandemic: A self-reporting approach. Food Secur. 2020, 13, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. Beyond the throwaway society: Ordinary domestic practice and a sociological approach to household food waste. Sociology 2012, 46, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizeau, K.; von Massow, M.; Martin, R. Household-level dynamics of food waste production and related beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours in Guelph, Ontario. Waste Manag. 2015, 35, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werf, P.; Seabrook, J.A.; Gilliland, J.A. Food for thought: Comparing self-reported versus curbside measurements of household food wasting behavior and the predictive capacity of behavioral determinants. Waste Manag. 2020, 101, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, C.; Alboni, F.; Falasconi, L. Quantities, determinants, and awareness of households’ food waste in Italy: A comparison between diary and questionnaires quantities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høj, S.B. Metrics and Measurement Methods for the Monitoring and Evaluation of Household Food Waste Prevention Interventions. Master’s Thesis, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Requena-Sanchez, N.; Carbonel-Ramos, D.; Campodónico, L.F.D. A novel methodology for household waste characterization during the COVID-19 pandemic: Case study results. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2021, 24, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, B.; Reynolds, C.; Martins, C.A.; Frankowska, A.; Levy, R.B.; Rauber, F.; Osei-Kwasi, H.A.; Vega, M.; Cediel, G.; Schmidt, X.; et al. Food insecurity, food waste, food behaviours and cooking confidence of UK citizens at the start of the COVID-19 lockdown. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 2959–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Lopez, A.; Cicatiello, C.; Principato, L.; Secondi, L. Consumer expenditure, elasticity and value of food waste: A quadratic almost ideal demand system for evaluating changes in Mexico during COVID-19. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 82, 101065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasko, Z.; Berjan, S.; Bilali, H.E.; Allahyari, M.S.; Despotovic, A.; Vukojević, D.; Radosavac, A. Household food wastage in Montenegro: Exploring consumer food behaviour and attitude under COVID-19 pandemic circumstances. Br. Food J. 2022, 125, 1516–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berjan, S.; Vaško, Ž.; Hassen, B.T.; El Bilali, H.; Allahyari, M.S.; Tomić, V.; Radosavac, A. Assessment of household food waste management during the COVID-19 pandemic in Serbia: A cross-sectional online survey. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 11130–11141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogevska, Z.; Berjan, S.; Bilali, H.E.; Sadegh Allahyari, M.; Radosavac, A.; Davitkovska, M. Exploring food shopping, consumption and waste habits in North Macedonia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 82, 101150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Music, J.; Charlebois, S.; Spiteri, L.; Farrell, S.; Griffin, A. Increases in household food waste in Canada as a result of COVID-19: An exploratory study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werf, P.; Seabrook, J.A.; Gilliland, J.A. The quantity of food waste in the garbage stream of southern Ontario, Canada households. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Massow, M.; Parizeau, K.; Gallant, M.; Wickson, M.; Haines, J.; Ma, D.W.L.; Wallace, A. Valuing the multiple impacts of household food waste. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Mones, B.; Barco, H.; Diaz-Ruiz, R.; Fernandez-Zamudio, M.A. Citizens’ food habit behavior and food waste consequences during the first COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebauer, S.; Fleiß, J.; Schweighart, M. A household is not a person: Consistency of pro-environmental behavior in adult couples and the accuracy of proxy-reports. Environ. Behav. 2017, 49, 603–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzawanda, B.; Moyo, G.A. Challenges associated with household solid waste management (SWM) during COVID-19 lockdown period: A case of ward 12 Gweru City, Zimbabwe. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werf, P.; Larsen, K.; Seabrook, J.A.; Gilliland, J. How neighbourhood food environments and a pay-as-you-throw (PAYT) waste program impact household food waste disposal in the city of Toronto. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çavuşa, O.; Bayhanb, I.; Ismail, B.B. An overview of the effect of COVID-19 on household food waste: How does the pandemic affect food waste at the household level? Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2022, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jribi, S.; Ismail, B.H.; Doggui, D.; Debbabi, H. COVID-19 virus outbreak lockdown: What impacts on household food wastage? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 3939–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal Filho, W.; Voronova, V.; Kloga, M.; Paço, A.; Minhas, A.; Salvia, A.L.; Ferreira, C.D.; Sivapalan, S. COVID-19 and waste production in households: A trend analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 777, 145997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neyra, J.M.V.; Cequea, M.M.; Schmitt, V.G.H.; Ferasso, M. Food consumption and food waste behaviour in households in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 4477–4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicewicz, R.; Bilska, B. Analysis of Changes in Shopping Habits and Causes of Food Waste Among Consumers before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland. Environ. Prot. Nat. Resour. 2021, 32, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridis, P.K.; Zacharatos, T.V. Food waste during COVID-19 lockdown period and consumer behaviour—The case of Greece. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 83, 101338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brizi, A.; Biraglia, A. “Do I have enough food?” How need for cognitive closure and gender impact stockpiling and food waste during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-national study in India and the United States of America. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 168, 110396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, K.; Vizcaino, M.; Wharton, C. COVID-19-related changes in perceived household food waste in the United States: A cross-sectional descriptive study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wang, C.; Cui, Z.; Liu, X.; Jiang, J.; Yin, J.; Feng, H.; Dou, Z. COVID-19 affected the food behavior of different age groups in Chinese households. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejia, D.; Diaz, M.; Charry, A.; Enciso, K.; Ramírez, O.; Burkart, S. “Stay at home”: The effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on household food waste in Colombia. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, e0260244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Madni, G.R.; Anwar, M.A. Exploring rural inhabitants’ perceptions towards food wastage during COVID-19 lockdowns: Implications for food security in Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principato, L.; Secondi, L.; Cicatiello, C.; Mattia, G. Caring more about food: The unexpected positive effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on household food management and waste. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 82, 100953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scacchi, A.; Catozzi, D.; Boietti, E.; Bert, F.; Siliquini, R. COVID-19 lockdown and self-perceived changes of food choice, waste, impulse buying and their determinants in Italy: QuarantEat, a cross-sectional study. Foods 2021, 10, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittuari, M.; Masotti, M.; Iori, E.; Falasconi, L.; Gallina Toschi, T.; Segrè, A. Does the COVID-19 external shock matter on household food waste? The impact of social distancing measures during the lockdown. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, B.T.; El Bilali, H.; Allahyari, M.S.; Karabašević, D.; Radosavac, A.; Berjan, S.; Vaško, Ž.; Radanov, P.; Obhođaš, I. Food behavior changes during the COVID-19 pandemic: Statistical analysis of consumer survey data from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, B.T.; El Bilali, H.; Allahyari, M.S.; Berjan, S.; Fotina, O. Food purchase and eating behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey of Russian adults. Appetite 2021, 165, 105309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, I.M.; Fernandez-Zamudio, M.A.; Vidal-Mones, B.; Martins, R.B. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on Portuguese households’ food waste behaviors. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2020, 26, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, E.L.; Haszard, J.; Egli, V.; Roy, R.; Te Morenga, L.; Teunissen, L.; Decorte, P.; Cuykx, I.; De Backer, C.; Gerritsen, S. Less food wasted? Changes to New Zealanders’ household food waste and related behaviours due to the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbitt, C.W.; Babbitt, G.A.; Oehman, J.M. Behavioral impacts on residential food provisioning, use, and waste during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassen, T.B.; Hamid, E.B.; Allahyari, M.S. Impact of COVID-19 on food behavior and consumption in Qatar. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, G.; Cerroni, S.; Nayga, R.M.; Yang, W. Impact of COVID-19 on Household Food Waste: The Case of Italy. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 585090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetkin Özbük, R.M.; Coşkun, A.; Filimonau, V. The impact of COVID-19 on food management in households of an emerging economy. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 82, 101094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Lombardo, C.; Cerolini, S.; Franko, D.L.; Omori, M.; Linardon, J.; Guillaume, S.; Fischer, L.; Tyszkiewicz, M.F. “Waste not and stay at home” evidence of decreased food waste during the COVID-19 pandemic from the U.S. and Italy. Appetite 2021, 160, 105110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filimonau, V.; Vi, L.H.; Beer, S.; Ermolaev, V.A. The COVID-19 pandemic and food consumption at home and away: An exploratory study of English households. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 82, 101125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Bunditsakulchai, P.; Zhuo, Q. Impact of COVID-19 on food and plastic waste generated by consumers in Bangkok. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaco, R.; Hoehn, D.; Laso, J.; Margallo, M.; Ruiz-Salmón, J.; Cristobal, J.; Kahhat, R.; Villanueva-Rey, P.; Bala, A.; Batlle-Bayer, L.; et al. Food waste management during the COVID-19 outbreak: A holistic climate, economic and nutritional approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 742, 140524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharadin, B.; Yu, Y.; Jaenicke, E.C. Household time activities, food waste, and diet quality: The impact of non-marginal changes due to COVID-19. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2021, 19, 399–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Jaenicke, E.C. Estimating Food Waste as Household Production Inefficiency. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 102, 525–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herpen, E.; van der Lans, I.A.; Holthuysen, N.; Nijenhuis-de Vries, M.; Quested, T.E. Comparing wasted apples and oranges: An assessment of methods to measure household food waste. Waste Manag. 2019, 88, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visschers, V.; Wickli, N.; Siegrist, M. Sorting out food waste behaviour: A survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghesi, G.; Morone, P. A review of the effects of COVID-19 on food waste. Food Secur. 2022, 15, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmanesh, M.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Nilashi, M.; Tseng, M.L.; Senali, M.G.; Abbasi, G.A. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on household food waste behaviour: A systematic review. Appetite 2022, 176, 106127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Number | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| #1 | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((‘food wast*’) OR (‘organic wast*’)) |

| #2 | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((‘house*’) OR (‘home*’) OR (‘resident*’) OR (‘consumer’)) |

| #3 | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((‘COVID’) OR (‘COVID-19′) OR (‘coronavirus’) OR (‘SARS-CoV-2′) OR (‘pandemic’) or (‘lockdown’) OR (‘outbreak’)) |

| #1 AND #2 AND #3 |

| Study | Geography | Sample Size | Time of DataCollection | Quantity and Composition of Food Waste (Kilogram per Capita per Week) | Change in Food Waste Quantity and Composition during COVID-19 Compared to before the Outbreak |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [15] | London, ON, Canada | 100 households | June 2020 | Total food waste: 0.96 | Not reported |

| Avoidable food waste: 0.49 | |||||

| Fruit and vegetables: 0.16 | |||||

| Bread and bakery: 0.10 | |||||

| Other food: 0.10 | |||||

| Dried food: 0.06 | |||||

| Meat and fish: 0.05 | |||||

| Dairy: 0.02 | |||||

| Unavoidable food waste: 0.47 | |||||

| Fruit and vegetables: 0.32 | |||||

| Other food: 0.09 | |||||

| Meat and fish: 0.07 | |||||

| [16] | London, ON, Canada | 99 households | June 2020 | Total food waste: 0.97 | Total food waste: +22.5% |

| Avoidable food waste: 0.53 | Avoidable food waste: +0.4% | ||||

| Fruit and vegetables: 0.19 | Fruit and vegetables: −21.0% | ||||

| Bread and bakery: 0.09 | Bread and bakery: −14.7% | ||||

| Other food: 0.10 | Other food: +227.5% ** | ||||

| Dried food: 0.06 | Dried food: −17.6% | ||||

| Meat and fish: 0.06 | Meat and fish: +4.4% | ||||

| Dairy: 0.02 | Dairy: +25.6% | ||||

| Unavoidable food waste: 0.45 | Unavoidable food waste: +65.5% ** | ||||

| Fruit and vegetables: 0.32 | Fruit and vegetables: +78.1% ** | ||||

| Other food: 0.07 | Other food: +83.9% * | ||||

| Meat and fish: 0.06 | Meat and fish: +12.8% | ||||

| [17] | Guelph, ON, Canada | 19 households | July to August 2020 | Total food waste: 1.08 | Total food waste: +0.4% |

| Avoidable food waste: 0.47 | Avoidable food waste: −32% | ||||

| Fruit and vegetables: 0.29 | Fruit and vegetables: −5% | ||||

| Other: 0.18 | Other: −54% * | ||||

| Unavoidable food waste: 0.61 | Unavoidable food waste: +58% ** | ||||

| Fruit and vegetables: 0.43 | Fruit and vegetables: +48% * | ||||

| Other: 0.19 | Other: +89% ** | ||||

| [18] | Brno, Czech Republic | 900 households | May to June 2020 | Avoidable food waste: 0.44 | Avoidable food waste: decreased |

| Study | Geography | Sample Size | Time of Data Collection | Perceived Quantity and Composition of Food Waste (Kilograms per Capita per Week) | Perceived Changes in Food Waste Quantity and Composition during COVID-19 Compared to before the Outbreak |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [19] | Italy | 15 households | March to May 2020 | Total food waste: 0.63 | Not reported |

| Vegetables and legumes: 0.26 | |||||

| Fruit: 0.20 | |||||

| Fish and fish products: 0.07 | |||||

| Meat and meat products: 0.05 | |||||

| Milk and dairy products: 0.03 | |||||

| Pasta and rice: 0.01 | |||||

| Bread and bakery products: 0.01 | |||||

| [25] | Arequipa, Peru | 44 participants | September to October 2020 | Total organic waste: 1.34 | Total organic waste: +17% 1 |

| Food scraps and garden waste: 0.93 | |||||

| Leftover food and stews: 0.41 |

| Study | Geography | Sample Size | Time of Data Collection | Perceived Quantity and Composition of Food Waste | Perceived Changes in Food Waste Quantity and Composition during COVID-19 Compared to before the Outbreak |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [61] | United Kingdom | 16 interviewees | June 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: some interviewees self-reported a decrease, while others self-reported an increase |

| Study | Geography | Sample Size | Time of Data Collection | Perceived Quantity and Composition of Food Waste | Perceived Changes in Food Waste Quantity and Composition during COVID-19 Compared to before the Outbreak |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [63] | Spain | Not reported | March and April 2020 | Not reported | Total food waste: +12% |

| [64] | United States | 3298 observations | Not applicable | 32% of total food purchased was wasted | Not reported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Everitt, H.; van der Werf, P.; Gilliland, J.A. A Review of Household Food Waste Generation during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075760

Everitt H, van der Werf P, Gilliland JA. A Review of Household Food Waste Generation during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2023; 15(7):5760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075760

Chicago/Turabian StyleEveritt, Haley, Paul van der Werf, and Jason A. Gilliland. 2023. "A Review of Household Food Waste Generation during the COVID-19 Pandemic" Sustainability 15, no. 7: 5760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075760

APA StyleEveritt, H., van der Werf, P., & Gilliland, J. A. (2023). A Review of Household Food Waste Generation during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 15(7), 5760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075760