Abstract

In the endeavour towards an inclusive society, work integration social enterprises (WISEs) play an important role in workplaces and labour market. Customers of WISEs are an underexplored field, and thus, this study looked at the influence of WISEs on customers using the concept of customer value. It deployed qualitative and quantitative study of two cases of WISEs in the Dutch agriculture and food industry. Market basket analysis was conducted to find interactions between customer characteristics and customer values. The results of our study show that taste as a functional value is a minimum requirement as well as a unique selling proposition for these two cases. The fact that they are a WISE was presented at different explicitness levels to customers: sometimes with a direct statement, other times with a phrase or visual hinting at this social aspect. Customers not always received this message or misinterpreted it as the WISEs intended. The results also indicate that products from these two cases are not associated with lower quality despite findings by earlier studies on socially oriented organisations. However, it is yet to be explored how the general Dutch population perceives the products and services of WISEs.

1. Introduction

Social inclusion and equality are of great importance in today’s world [1]. Everyone has the right to participate in society according to their own capabilities [2,3]. The field of the labour market and work is not an exception. Regarding social inclusion in the Dutch context, the Participation Act was enacted in 2015, substituting several older acts. Its aim is to encourage and support people with disadvantages in the labour market to find work by a regular employer [4]. The so-called “Work Integration Social Enterprises (WISEs; also known as social firms)” provide opportunities for people with disadvantages in the labour market to be trained and/or to work with other co-workers, while maintaining their business financial sustainability through trade [5], and thus are aligned with the objective of the Participation Act. WISEs are more socially and economically integrated into the rest of the society than the previous model of sheltered workshops [6].

Generally speaking, the WISEs are categorised as a type of social enterprise (SE)—businesses that prioritise the creation of social and/or environmental impact than profit-making for their owners or shareholders [5]. Other types of impact include but are not limited to circular and sustainable production and the development of a fair supply chain [7]. Aside from the direct impact on beneficiaries (e.g., nature and people with disadvantages), SEs also indirectly impact, for instance, the government, other enterprises, and consumers [8]. However, the indirect impact of SEs and WISEs is an underexplored field.

One way to look at the indirect impact of WISEs is through company—customer interaction using the concept of customer value (CV). CV can be defined as benefits that customers can expect from a product or a service [9,10]. Customer value proposition (CVP) is a strategic tool for organisations to communicate CV to their target customers [11]. It can be designed on four aspects, which are (1) perspective, (2) explicitness, (3) granularity, and (4) focus. CV is something that is mutually determined through the experience of the customers and not a one-way delivery of value predetermined by the supplier [11,12]. It may also reflect customers’ social and environmental concerns.

Several types of CV are explained in the literature, and their total number varies. One study describes 30 elements of CV divided into four categories: functional (e.g., quality, sensory appeal, reduces effort), emotional (e.g., design, entertainment, wellness), life-changing (e.g., self-actualisation, provides hope), and social impact (i.e., self-transcendence) [13]. The study starts with the view that there are underlying motives to more apparent attributes that customers say they appreciate. Their categorisation extends Maslow’s hierarchy of needs [14] in the context of consumers.

Customer’s perceived value is a precursor to customer loyalty. Loyalty can be divided into two types: behavioural and attitudinal [15]. Examples of the former include repeat purchases and high amount of purchases [16]. However, the behaviour may be habitual, thus easily influenced by situational factors. In contrast, the latter entails brand preference, commitment, trust, and satisfaction [17] and is less prone to situational factors.

As mentioned previously, customers of WISEs are an underexplored field. A study on Dutch SEs recommended future studies to investigate multiple questions [8], including “how can SEs become more effective in raising awareness and growing their customer base at the same time?”. This study aims to investigate customer value—segment interaction of WISEs in the Netherlands. The country is reported to have an SE sector that uses innovative approaches and tries to mobilise customers [18]. With this objective, this research could contribute to the sector involving more consumers in their activities and mission and taking steps towards a more inclusive society. This is vital because acts of individual SEs and consumers can lead to social issues gaining more attention and support, and thus niche movements leading to a systemic level change in regimes such as policy, market, and culture [19]. Given the potential of the indirect impact of WISEs, our research will attempt to answer the question—“How do different forms of customer value in the Dutch WISE sector influence the response of different customer segments?”

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

This study took a mixed-methods, abductive approach in order to explore CV of Dutch social enterprises. It was a multiple-case study instead of a single case study to better understand if the findings were valuable or not [20]. To triangulate the findings, both desk and field research, a combination of multiple and various stakeholders in data collection, and qualitative and quantitative data analysis methods were used.

2.2. Introduction of Cases

Two cases of Dutch WISEs in the agri-food sector with their own sales point and thus direct sales to customers were selected based on convenience sampling; they were accessible and willing to participate. A case study approach was suitable for this pilot study, which aimed to explore the characteristics of pioneering WISEs in depth. For the same reason, the cases were selected purposively based on the researcher’s experience and judgement on their suitability. Background information and customer interviewee profile of the two cases are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Background information of the two cases and customer interviewee profile.

2.2.1. Case #1: Tuinderij De Es

Tuinderij De Es had its 40th anniversary in 2021. Its current owners took over in 2012. The farm produces various types of organic vegetables and herbs, which are sold at the Friday market in Den Bosch, its own farm shop in Haaren, via online grocery platforms, colleague farmers and retailers, wholesaler, to restaurants. It is a “zorgtuinderij” (care farm) and as of 2022, it offers daycare service to 17 elderly people and 11 people with psychological conditions and those who want to make a step towards regular employment. The 11 people participate in farming activities.

2.2.2. Case #2: Het Theezaakje

Het Theezaakje was established in 2015, with a store on one of the main shopping streets in Nijmegen. The name means “the tea shop”, and the company sells more than 100 types of tea. They are described as “vrolijke thee met een sociaal verhaal” (cheerful tea with a social story). The company is organised as a workers’ cooperative with 12 people in the reintegration program and four paid employees (including the two board members).

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Document Secondary Data

Being a multiple-case study, it was suitable to use secondary document data [21]. To construct the first overview of CV and segments before deepening and validating through interviews, we collected textual, audio, and visual materials, both online and offline. Online materials such as websites and social media pages were screenshots using “NCapture”, which is a web browser extension compatible with the qualitative data analysis program NVivo 12. As for physical materials such as packaging, photos were taken to be processed on NVivo 12.

2.3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

Interviews were conducted to deepen and validate the emerging topics from two perspectives—companies and customers. The format was semi-structured, which allowed the interviewee to elaborate on a topic according to the flow of the conversation and allowed new themes to emerge and evolve over the course of each session and series of sessions [21]. This way, this exploratory research of an understudied field was not limited by existing concepts.

Semi-structured interviews with representatives of the cases served to deepen and validate the first overview of their CV, which was based on the researcher’s observation from secondary data. This provided insight into the issue from the company perspective, in other words, what CV the WISEs themselves think they are creating and delivering, to whom.

Individual customers of the cases were interviewed to gain insights into CV from the customer perspective. This prevented the study from being a one-sided analysis. An interview guide was created in English and Dutch, and the Dutch version was checked with native Dutch speakers in the researcher’s network. Then, the questions were tested at case #2, revised, and used at both cases for official data collection. The English version of the interview guide can be found in Appendix A.

The customer interviews took place on a Saturday in April 2022, at the owned sales points. All customers were approached during or after their purchase if the timing allowed the researcher to do so. The interview was introduced as “research on purchase from the shop”. The researcher first asked a question to initiate the conversation. Based on the answer and the interview guide, follow-up questions were asked to obtain more elaborate explanations on why the interviewees were shopping there. The follow-up questions also ensured that the conversation was not irrelevant to the research and that data was collected efficiently within the limited time—each session took around 3 min. This way, interviewees were not steered so much to give answers based on social desirability but were still guided to produce data relevant enough. Still, social desirability bias was not completely avoidable, and this was considered when analysing and discussing the results.

2.4. Data Analysis

The collected data was processed and analysed both qualitatively and quantitatively. Thematic analysis is a commonly used method for qualitative data and can integrate data derived from different sources [21]: the researcher coded the texts, interview notes, and visual materials to look for emerging themes. The main analysis tool was NVivo 12, and Microsoft Excel was used where necessary to organise and compare themes per question and case/interviewee. The analysis was conducted per case and per perspective to distinguish each. Inductive approach was used since the aim was to explore the topic. For CV-related topics in customer interviews, the latent approach was used to capture the underlying CV behind the attributes customers say they appreciate, which was possible to interpret based on their statement [13].

For instance, when a customer stated “For this store, it’s important that everything is organic, because that’s why we come here”, it was categorised as “organic”. When a customer stated “[The tea] reminds me of my home country. I am used to the original, good quality tea”, the CV this statement refers to was categorised as “nostalgia” for the first part and “quality” for the second part.

The first step of thematic analysis, familiarisation with textual and visual data, was performed in their original language, and in the second stage, the data was coded to English terms. Translation was based on the researcher’s language skills, and when unsure, online dictionary and translator and native Dutch speakers in the researcher’s network were consulted.

Market basket analysis (MBA) was deployed to make an assessment of behavioural elements of customers and also to identify associations between different types of CV (in the explanation below, referred to as “items”). The association rule mining approach, which is an unsupervised machine learning method, has been used extensively in the science domain [22,23]. The method of rule mining uncovers the associations between binary or categorical variables in a large dataset. Twelve items were used in the MBA as listed in Appendix B.

Support and confidence are the key measurements in the rule of associations. Support represents the popularity of a combination of items in all transactions. The higher the support, the more frequently the itemset occurs. Confidence can be interpreted as the likelihood of purchasing a combination of items when the customer purchases one of the items. The confidence value of 0.65 was chosen as the threshold based on the classical rule mining procedure [23]. Rules of associate analysis are generated from the frequent itemset using an algorithm, which guarantees that the support of the rule is greater than or equal to the minimum support (=0.005). Overall, the rule with the confidence value 0.65 means 65% of customers who jointly buy items 1 and 2, while 5% of support value (=0.005) shows that this combination covers 5% of transactions in the database. R packages Arules and ArulesViz with default “Apriori” algorithm were used for this analysis with support and confidence set at 0.005 and 0.65, respectively. The algorithm computes a lift value that determines the strength of the association pattern between two items. Larger the lift value, stronger the link between the two. Rules with high support are preferred due to the fact that they are likely to be applicable to a large number of future transactions.

In addition to MBA, logistic regression was used to statistically analyse the significance of each explanatory variables. Explanatory variables are gender, generation, product, organic, business, shop, assortment, convenience, and feeling. Target variables are repeater and awareness that the company is a WISE. Also, multivariate analysis was tested by using those variables that show significance in a univariate analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Visual and Textual Analysis

Each case presented its CV through various means. For instance, sensory-related aspects (i.e., taste, smell, freshness) was communicated on packaging, website, social media, and in-store. To give some examples, the packaging of Tuinderij De Es says “We sell tasty, fresh, healthy, and local food” (Figure 1). In the store of Het Theezaakje, customers could smell samples of all the teas. Additionally, at Tuinderij De Es, vegetables and fruits are displayed on the shelf.

Figure 1.

Het Theezaakje packaging (left) and Tuinderij De Es packaging (right).

Aspects related to production and sourcing were presented similarly. Examples included a label on the packaging that says EU organic label and Dutch EKO label on packaging and website (Tuinderij De Es) and an explanation of sustainable procurement on the packaging (Het Theezaakje) (Figure 1).

The fact that the cases are WISEs was communicated in various ways. The packaging of Het Theezaakje has a label that says “cheerful tea with a social story”, the logo of Social Enterprise NL, and a text explaining the mission. At the Tuinderij De Es farm shop, there are windows that allow customers to see people working in the greenhouse. In addition, the customers are free to walk into the greenhouse and the garden. The shops of both cases also have posters that explain how they help people with distance from the labour market (and in the case of former, also about elderly care). Het Theezaakje have a phrase on their web shops pointing out the social impact that a customer has when purchasing from these companies:

“Did you know that by drinking our tea, you create nice workplaces for people with a distance from the labour market?” (Het Theezaakje)

Finally, the packaging design of each case reflects their take on the environment. Tuinderij De Es uses a brown paper bag, while Het Theezaakje uses biodegradable bags and sells loose leaf tea that does not require additional packaging per portion.

3.2. Quantitative Analysis of Customer Interviews

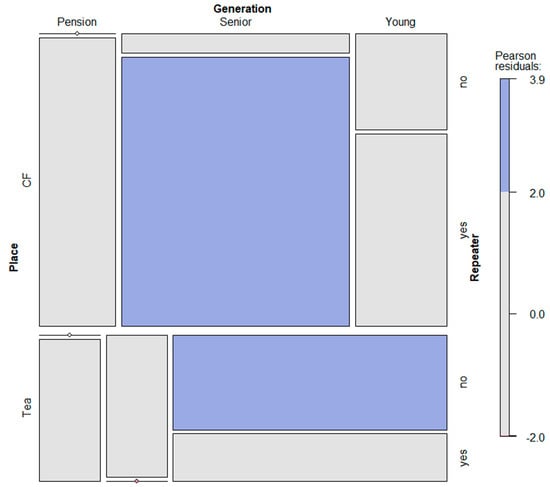

The distribution of our dataset in the relation between shops (local), the generation of the customers, and the repeater are shown in Figure 2. Mosaic plots show our data as is, and there is no attempt to generalise to the whole population. Regarding the case of Tuinderij De Es, seen on the top side of Figure 2, the frequency of the customers who are a senior and a repeater is significantly higher than expected under the null model. In contrast, at Het Theezaakje, on the bottom side of Figure 2, the group of young non-repeaters is significantly large.

Figure 2.

Mosaic plot showing the distribution of data sample (customer generations and repeaters) in two locations (CF = Tuinderij De Es; Tea = Het Theezaakje). Blue means there are more observations in the cell than would be expected under the null model (independence), while red colour denotes the opposite situation. The p-value of the Chi-square test is 0.00012054.

The list of CV categories mentioned in customer interviews is presented in Table 2 based on their frequency. The definition of the categories and more specific attributes under each are explained in Appendix C. The analysis indicates that “product” is the most commonly mentioned category in both cases. It includes taste (n = 6 at Tuinderij De Es; n = 5 at Het Theezaakje) and quality (n = 5 at Tuinderij De Es; n = 2 at Het Theezaakje). At Tuinderij De Es, organic was also mentioned by over half of the customers, which was also related to other categories such as product (i.e., taste) and business (i.e., sustainability and health). The attribute “social”, related to the social aspect of these WISEs and categorised under “business”, was only mentioned by one customer at Tuinderij De Es.

Table 2.

CV categories appreciated by customers in the two cases. Multiple answers possible.

- Using the categories, univariate and multivariate analysis was conducted to look for the significance of several factors (categories) in determining whether a customer is a repeater (Table 3) and whether they are aware of the social aspect (Table 4).

Table 3. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis showing predictors of repeater with odds ratio (OR), Wald test, and p-value. Asterisk mark (*) refers to statistical significance (p value < 0.05).

Table 3. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis showing predictors of repeater with odds ratio (OR), Wald test, and p-value. Asterisk mark (*) refers to statistical significance (p value < 0.05). Table 4. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis showing predictors of awareness with odds ratio (OR), Wald test, and p-value. Asterisk mark (*) refers to statistical significance (p value < 0.05).

Table 4. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis showing predictors of awareness with odds ratio (OR), Wald test, and p-value. Asterisk mark (*) refers to statistical significance (p value < 0.05). - When it comes to the repeater, a couple of categorical variables show a significant difference. The generation has a significant difference (p value < 0.05). The senior generation shows a significant difference compared to other generations. The business has a slightly significant difference (p < 0.1). However, no interactive effect between Generation and Business has been found.

- Regarding awareness, the following variables show a statistical significance: Place (p < 0.01); Generation (p < 0.05); Organic (p < 0.05), Product (p < 0.05); Business (p < 0.1). Senior generation (p = 0.002998) has more significance compared to other generations. On the contrary, the young generation does not show any significance in awareness.

- No interactive factors were found regarding awareness: (Generation * Organic), (Generation * Product), (Place * Generation), (Place * Organic), (Place * Product). In addition, gender has no significance.

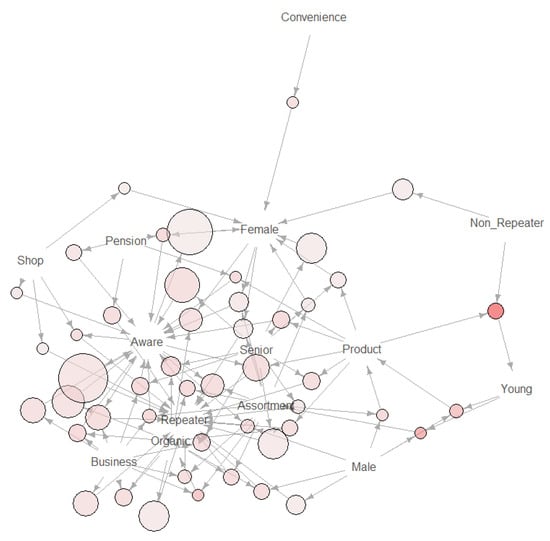

A so-called ‘basket analysis’ shows differences in the types of the items (answers) that the clients chose (Figure 3). As the result of our analysis, 48 rules were generated with the lift (between 1.076 and 2.6) by the default algorithm. A couple of the types of the answers do not appear in Figure 3, such as “Feeling”, due to the low frequent item set, which does not satisfy the minimum value of the support constraint (=0.005). In Figure 3, the position of “Non-Repeater” customers are isolated, seen in the upper right, while “Repeater” is enveloped by different types of answers such as “Aware”, “Assortment”, “Organic”, and “Business”. The large number of nodes are linked to the “Senior”, compared to “Young”.

Figure 3.

Outcome of market basket analysis for the interaction between customer characteristics and customer values. In this figure, the arrows indicate the relationship rules, and the size of the circle represents the level of confidence associated with the rule. The colour exhibits the level of lift with the range of 1.076–2.6. The support value is in the range between 0.103 and 0.615.

3.3. Interviews with Customers and Company Representatives

In line with the quantitative analysis of customer interviews in which “taste” was a most frequent word, company representatives explained how important taste and quality is:

“The other two market stalls, they are also local, so that’s not distinguishing. It’s more that …we take care of the quality. The quality is on our side…”(Tuinderij De Es, representative)

Compared to taste and quality, the social aspect seems to be lower in importance in terms of CV:

“It doesn’t matter [that it is a care farm]”(Tuinderij De Es, customer-female-repeater)

“I suspect that not a lot of customers know that we are a social enterprise”(Het Theezaakje, representative)

In fact, only 3 out of 13 interviewees at Het Theezaakje knew that the company was an SE. The researcher asked those who did not know about the “social story” what they thought it was about. Their answers were either donation of profit or fair-trade concept. In other words, the social aspect was not (correctly) conveyed to the customers.

At the same time, there are customers who do recognise and appreciate the social mission that the companies have.

“It’s not that I would stop coming here if it were not a care farm, but what they do is very beautiful…It’s a bit like the chicken and the egg story, it is what makes De Es a whole, it is what De Es is.”(Tuinderij De Es, customer-female-repeater)

The companies themselves do want to communicate their social aspect to their customers.

“…I think so [we want the customers to be more aware of our social story], we should emphasize it a bit more. we should make more use of that cross-linkage [between different activities on the farm]. So what I did in the shop now is that I put an infographic of the farm. To inform people what we are doing on the whole farm, not only that we have a shop.”(Tuinderij De Es, representative)

“…we have it [social story] on our packages, we also try to highlight it on our Instagram, a blend of social story and product, so in that sense, we are open and forward about it.”(Het Theezaakje, representative)

Twenty-four out of twenty-six interviewees at Tuinderij De Es knew that it was a care farm. This might be because 23 out of 26 were repeating customers. A relatively new customer who started shopping at Tuinderij De Es half a year ago said that he did not know but he could imagine because of the “social environment” of the farm.

Tuinderij De Es and Het Theezaakje work with organic products. They have their own motivations for this.

“At some point, we made the decision because we are a social enterprise, we care about people, but if we care about people, we also care about the plants and planet, because people live on this planet.”(Het Theezaakje, representative)

At Het Theezaakje, “organic” was not really a distinctive attribute for customers (3 out of 13 customer interviewees mentioned it). In contrast, it was by far the most frequently mentioned aspect by Tuinderij De Es customers. Interestingly, when they were asked if they would purchase from the farm even if there were non-organic products, some customers said they would not mind because they trusted the owners.

“I assume they don’t just put something here that actually contradicts the rest.”(Tuinderij De Es, customer-female-repeater)

4. Discussion

4.1. Development of WISEs

WISEs are said to have originated in the 20th century in multiple countries in the social context of neoliberalism, globalisation, and inclusion [24,25,26]. The regulatory, economic, and social environment surrounding WISEs varies among countries, for instance, with different levels of financial support from the government. In the Netherlands, the Participation Act was enacted in 2015 to reduce welfare expenditure and enable a more flexible approach to the varying needs of people at a distance from the labour market [4]. The so-called “social ontwikkelingsbedrijf” (social development company) plays an important role in actually creating work and training places, with financial and other support from municipalities [27]. Like this, WISEs fill in the gap in the social needs that neither the traditional government nor companies can meet, commonly called “the third sector” [24].

The growth of social enterprises, in general, can be compared to activities related to corporate social responsibility (CSR). CSR developed amidst rising concerns about companies’ social and environmental externalities [28]. Yet, it is distinct from CSR in that they do not have social and/or environmental impact as the priority [18]. WISEs can also be discussed in the context of creating shared value (CSV) proposed by Porter and Kramer [29]. This concept is a holistic combination of various concepts, including CSR and social entrepreneurship. However, it has received criticism that it does not tackle the fundamental issues of capitalism that it claims to do [30]. Thus, it can be considered somewhat different from social entrepreneurship, which in the Dutch context is observed to do things differently, innovatively, and driven by intrinsic motivation [18].

4.2. Customer Value among WISEs

Purchases from WISEs support the social participation of disadvantaged people and an inclusive society. Therefore, it can be considered a type of ethical consumption—making purchase decisions based on values embracing environmental and/or social sustainability [31,32]. Research implies that the types of CV identified in more general studies are also relevant to ethical consumption. First of all, ethical consumption, in general, can be driven by intrinsic and extrinsic motivations [33]. The former includes empathy and self-reflexive consciousness [34,35]. For consumers who identify themselves as ethically minded, ethical consumption is part of a search for a morally good life [36]. Social status and reputations are examples of extrinsic motivations [34].

Research has shown that SEs can promote ethical consumption [8], and there are several proposed methods and theories. As a starting point, non-SE entities such as NGOs and governments also influence consumer attitude and behaviour [37,38]. However, SEs are unique in that they use concrete and marketable products and services to reach consumers and give them “the power to change the industry” (Bas van Abel, founder of Fairphone. Quoted in [8]). Our study tried to explore how Dutch WISEs motivate customers to purchase their products and to influence customers regarding the social issue.

4.3. Characteristics of Customer Value

The observed types of CV (Table 2) are comparable to what was explained by other studies in general and those related to ethical consumption [13,39]. It is not surprising that as agri-food companies, “taste” was one of the most frequently mentioned CV types in both cases. This functional value acted not only as a minimum requirement, as found in a previous study [13] but also as a USP from both company’s strategy and customer perspective. In addition, some types of functional values (e.g., organic) substantiate the reason of existence and/or the story of the WISE. Some types of CV observed in previous studies, especially extrinsic motivations [34], were not observed. This may be due to social desirability bias or the framing of interview questions. They might be irrelevant for WISEs, but it is not to be concluded so.

Moving on to the “explicitness” of CVPs [11], our study shows a contrasting result between the two cases. On the one hand, Tuinderij De Es not always communicated its social aspect explicitly, but multiple customers considered it a logical, natural part of the whole organisation. This is because customers can feel the related values, as shown in the qualitative analysis of the interviews. A similar inference is made by Payne et al. (2017), where implicit CVP can be effective when it is embedded within the organisational culture.

On the other hand, Het Theezaakje’s stamp with the phrase “with a social story” (Figure 1) was misunderstood or not recognised. This is despite the elaborate explanations on the side of the packaging and online media. Apparently, some phrases are not easily linked to what they actually mean. This infers the “ineffectiveness” of a rather implicit CVP [11]. However, this mismatch between company’s claim and customer’s perception can also be attributed to a lack of “fit” between company’s offer and customer’s problem [40]. This situation also substantiates the view that CVP is mutually determined [12].

In the literature, the explicitness of sustainability is found to have varied effects, including both attracting and pushing away customers [41,42]. However, the existing studies are limited in the sector and relatively old, so it is unknown what effects exist in the WISE sector in the 2020s. It would probably be insightful to compare different explicitness. In fact, a brief observation of other WISEs in the Netherlands suggests that there are cases that present their social aspect more explicitly than the two cases in this study.

Both cases, although to a varying extent, showed a clear intention to communicate their social aspect to customers. This is in line with the motivation among Dutch SEs to influence customers and other organisations [7,18]. The results suggest that WISEs can be a touchpoint for customers to learn about the concept of an inclusive labour market. This might be achieved directly when customers read about the social aspect of company’s communication channel or less directly when customers see and feel the inclusive atmosphere. Especially, the latter seems to lead to the social aspect being naturally accepted by customers because it is “a part of the whole (organisation)”.

Despite the theory that SEs can change consumer norms and provide alternatives to consumers and empower them [8], and despite the expressions used by Het Theezaakje that buying their products can have a social impact, these were not really mentioned by customers (Table 2).

The choice regarding storytelling also concerns the growth stage [43] and the impact model of a WISE. As a smaller enterprise with a unique product/story, it might choose to enter the market with a niche strategy. When the core customer base is built, it might then appeal to a wider audience by being less niche, for instance, by using more major sales channels and toning down on social story. At this stage, the impact is created by increasing sustainable supply on the market, and possibly changing the norms of customers and industry [8].

4.4. Creating Customer Loyalty

When customers like certain aspects of the product/organisation, they come back to purchase again (Figure 3), which is a behavioural customer loyalty [16]. MBA shows that repeaters are attracted to various CV types, while first-time customers (non-repeaters) were connected to a few other items (Figure 3). This suggests that potential customers generally learn about the shop on a limited number of aspects and over time, they learn about and start to like other aspects. It should be noted that repeaters were not necessarily familiar with the social aspect, especially at Het Theezaakje. This, again, may be due to the implicitness of their CVP and, at the same time, implies that the social aspect is not a prerequisite for behavioural loyalty.

The customer interviews at Tuinderij De Es revealed that sometimes a key CV (i.e., “organic”) can be “compromised”. This implies that there are values that are as important or more important for customers. Such values included sustainability, local, and trust. The last aspect, trust in the organisation, supposedly occurs when there is coherency in the activities and values of the organisation [44], and those values match the personal values of the customers so that they can act according to their own determinations [45]. Purchasing from a company that one trusts is a characteristic of ethical consumption [46].

4.5. Characteristics of the Dutch Population and Customers

An increasing percentage of the Dutch consumers is influenced by “sustainability” “fair working conditions” etc. [47,48], but it is doubtful whether “work integration” is within their scope, as reflected in the customer interviews at Het Theezaakje. Work integration differs from other ethical consumption-related topics such as organic and fair trade in their public recognition (and thus the ease of association with “good practice”). Another difference between work integration and fair trade is that although both concern welfare of workers, the latter is in countries far away. It might be the case that consumers feel more comfortable to think about an issue that is not too closely related to their lives.

In addition, multiple studies in Europe and the Netherlands suggest that younger consumers are more informed and particular about sustainability and more likely to make sustainable purchasing decisions [49,50]. Meanwhile, in our study, this was not the case. The likeliness of a young customer in the two cases to be a repeater or aware about the social aspect is lower compared to other age groups (Figure 2; Table 4). Again, this raises a question whether work integration is within their interest of sustainability. Studies that suggest that younger consumers being more vulnerable to social norms, and this creates attitude–behaviour gap [51,52] support this question.

Finally, “quality stigma” is reported to be associated with products from CSR activities [39]. This is probably also relevant to WISEs. Similarly, customers might need to sacrifice this short-term benefit (quality) for a longer-term benefit (e.g., contribution to society) [53]. However, this sacrifice was not observed in this study. One reason may be that some customers did not know about the social aspect of the company, and thus no conscious “sacrifice” was made. In addition, non-customers, who presumably have more negative experience or image, were not studied. However, it may also be that people’s perceptions are changing, and they are expecting a higher quality from impact-first companies. This possibility is reflected in how some customers of Tuinderij De Es value the company’s wholesomeness. As a final note, the two cases themselves wanted to provide products with high quality. It would be insightful to analyse how relevant these results are to the overall image of the Dutch WISE sector.

4.6. Discussion on Methodology

Several points should be noted regarding the methodology. Firstly, even though this phase successfully combined company and customer perspectives of CVP, there is much room for deeper exploration from the customer perspective. For instance, the results suggest that if interviews had been conducted on a weekday, with online customers, and/or for a longer time per person, different conclusions might have been drawn. In addition, the size of the customer interviewees was too small to enable valid segmentation or development of customer profiles.

Another limitation is that the interviews with customers took place in-store for convenience, but it could have also been a source of social desirability bias. The questions could have been framed differently, for instance, to ask for a ranking of all CV types that a customer listed or to ask binominal (yes/no) questions to enable a more structured quantitative analysis. In addition, non-customers were not included in this study and thus, reasons for not purchasing were not explored in depth. This could be an agenda for future research. Nevertheless, this study contacted new customers, illustrating how non-customers came to be in touch with a WISE.

Moving on to the analysis method, this study deployed MBA as a tool to analyse relationship among various types of CV and demographic factors. It has been used for analysing consumer behaviour based on their purchase patterns (i.e., a large set of purchase records), but the application on CV is new. Despite the limited sample size in this research, the results suggest that MBA offers a new way to understand CV. In future research, with improvements in research methods such as the ones pointed out above, MBA could be utilised to analyse how different types of CV and combinations thereof lead to certain customer behaviours. The derived insights could be used for businesses to decide which types of CV to present together to which customer segments.

Moreover, in general, this is an exploratory pilot study. It did yield new insights about the issue. Yet, for the findings to be generalisable and validated, follow-up studies should be conducted on additional cases or with quantitative and/or experimental design. To give an example, experiments could be conducted to test how customers respond to a different presentation of a message on the packaging to better understand customer responses and their causes. Another example is to research outside the agri-food sector, since the most common CV types were quite specific to food.

Finally, these organisations are developing and changing. Thus, it would probably be insightful to design a longitudinal study where the development of these companies is followed over the years and how their CV and segment responses change.

5. Conclusions

This research explored the influence of WISEs on customers using the concept of customer value. The two cases of WISE in the Dutch agri-food sector were analysed quantitatively and qualitatively. For both cases, functional value, especially taste, was a main purchase driver and often the repurchase driver. Their social aspect (i.e., work integration) was not always known or clear to the customers. However, its related customer value does have the potential to be a USP and precursor to customer loyalty.

This study suggests that WISEs should provide high-quality products and/or services so as to deliver customer value and so as not to lead to quality stigma. Future research on customer aspects of WISEs can focus more on the social aspect, as well as use different research methods and samples to build on this small-scale, multiple-case studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.M. and P.M.; methodology, S.M.; software, S.M. and K.J.; validation, S.M. and P.M.; formal analysis, S.M. and K.J.; investigation, S.M.; resources, S.M. and K.J.; data curation, S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, K.J. and P.M.; visualisation, K.J.; supervision, S.M., K.J. and P.M.; project administration, S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Keiji Jindo wishes to acknowledge financial support (3710473400).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Below are the interview guides used for customer interviews at the stores of the two cases.

Tuinderij De Es

- -

- Is this your first visit? Or do you come here often?

- ○

- What makes you come back?

- -

- Did you know that all products here are organic?

- ○

- How important is this to you?

- ○

- Are you a frequent buyer of organic products?

- ○

- What would you think if there are local but not-organic products at this shop?

- -

- Did you know that this farm also has a social aspect, with care/“zorg”?

- ○

- How important is this to you?

- ○

- Were you familiar with the concept?

- ○

- What would you think if there are “social” but not-organic products at this shop?

Het Theezaakje

- -

- Is this your first visit? Or do you come here once in a while?

- ○

- What makes you come back?

- -

- Where do you usually buy your tea?

- ○

- What is important when you buy tea? Is it also relevant for this occasion?

- -

- Did you know that these tea also have a social story? Vrolijke thee met sociaal verhaal?

- ○

- What do you imagine from this?

- ○

- Are you familiar with the concept of “inclusive labour market”?

Appendix B

List of items used for MBA.

- -

- Age group

- -

- Gender

- -

- Repeater

- -

- Awareness

- -

- Assortment

- -

- Business

- -

- Convenience

- -

- Feeling

- -

- Organic

- -

- Product

- -

- Shop

Appendix C

Table A1.

Definitions of attributes and categories related to types of customer value.

Table A1.

Definitions of attributes and categories related to types of customer value.

| Category Name | Category Refers to… | Attribute Name | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assortment | Product assortment | Complete assortment | The product assortment is complete. |

| Diverse products | The product assortment is diverse. | ||

| Business | Business decision regarding scale and sustainability (social and environmental). Excludes “organic” 1 | Health | The products are good for health. |

| Local | The products are produced/sourced locally. | ||

| Packaging | The packaging is eco-friendly (i.e., biodegradable, reusable) | ||

| Seasonal | The fresh products are seasonal. | ||

| Small scale | The products are produced on a small scale. | ||

| Social | The company makes social impact. | ||

| Sustainability | The products and/or production methods are eco-friendly. | ||

| Convenience | Time and money-saving | Affordability | The products have an affordable price. |

| Location | The shop location is convenient. | ||

| Feeling | Personal, emotional experience of a customer | Nostalgia | The products remind me of home. |

| Reward | I feel good when I buy the products/from the shop. | ||

| Organic 1 | Organic production/sourcing | Organic | The products are produced/sourced organic. |

| Product | Inherent and sensory qualities of the products | Fresh | The products are fresh. |

| Quality | The product quality is good. | ||

| Smell | The products smell nice. | ||

| Taste | The products are tasty. | ||

| Shop | The experience of a customer in the shop, not related to the products. | Atmosphere | The atmosphere in the shop is nice. |

| People | The shop staff are friendly. | ||

| Purchasing experience | I enjoy the whole purchasing experience in the shop. |

1 “Organic” is both a category and an attribute on its own. This is because the number of codes under this attribute was substantially big compared to other attributes and also because this attribute was often connected to yet independent from other attributes such as local, quality, and taste.

References

- Oxoby, R. Understanding social inclusion, social cohesion, and social capital. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2009, 36, 1133–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN General Assembly. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Paris. 1948. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- UN General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities—Articles. New York. 2006. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-2.html (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Participatiewet. 2022. Available online: https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0015703/2022-08-26 (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Keizer, A.; Stikkers, A.; Heijmans, H.; Carsouw, R.; van Aanholt, W. Scaling the Impact of the Social Enterprise Sector; McKinsey and Company, 2016. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/scaling-the-impact-of-the-social-enterprise-sector#/ (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Zen A Net. Ōshu Ni Okeru Shōgaisha No Chūkanteki Shūrōbunnya Ni Kansuru Kaigai Shisatsu—Oranda Doitsu Hōmon Chōsa Hōkokusho. In Visit Abroad on Intermediary Employment of People with Disabilities in Europe—Report on Visit and Research in the Netherlands and Germany; Zen A Net: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Social Enterprise NL. De Social Enterprise Monitor 2019; Social Enterprise NL: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk, S.; Hillen, M.; Panhuijsen, S.; Sprong, N. Social Enterprises as Influencers of the Broader Business Community: A Scoping Study; Social Enterprise NL: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Reinartz, W. Creating enduring customer value. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 36–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, G. What Is Customer Value and How Can You Create It? J. Creat. Value 2020, 6, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.; Frow, P.; Eggert, A. The customer value proposition: Evolution, development, and application in marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 467–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Verleye, K.; Hatak, I.; Koller, M.; Zauner, A. Three Decades of Customer Value Research: Paradigmatic Roots and Future Research Avenues. J. Serv. Res. 2020, 23, 409–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almquist, E.; Senior, J.; Bloch, N. Customer Strategy. The Elements of Value; Harvard Business Review: Brighton, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossío-Silva, F.-J.; Revilla-Camacho, M.-Á.; Vega-Vázquez, M.; Palacios-Florencio, B. Value co-creation and customer loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1621–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Gaur, S.S.; Narayanan, A. Determining customer loyalty: Review and model. Mark. Rev. 2012, 12, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.K.; Niraj, R. Examining mediating role of attitudinal loyalty and nonlinear effects in satisfaction-behavioural intentions relationship. J. Serv. Mark. 2011, 25, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC. Building an ecosystem for social entrepreneurship: Lessons learned from The Netherlands; Pricewaterhouse Coopers B.V.: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. Multi-Level Perspective on System Innovation: Relevance for Industrial Transformation. In Understanding Industrial Transformation; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, J. Single Case Studies vs. Multiple Case Studies: A Comparative Study; Halmstad University: Halmstad, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; Pearson Education: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Aronne, G.; Giovanetti, M.; Guarracino, M.R.; de Micco, V. Foraging rules of flower selection applied by colonies of Apis mellifera: Ranking and associations of floral sources. Funct. Ecol. 2012, 26, 1186–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, D.; Haque, M.M.; Mande, S.S. Inferring Intra-Community Microbial Interaction Patterns from Metagenomic Datasets Using Associative Rule Mining Techniques. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, R.; Bidet, E. Social Enterprise for Work Integration in 12 European Countries: A Descriptive Analysis. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2005, 76, 195–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyssens, M.; Adam, S.; Johnson, T. Social Enterprise: At the Crossroads of Market, Public Policies and Civil Society; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cooney, K.; Nyssens, M.; O’Shaughnessy, M.; Defourny, J. Public Policies and Work Integration Social Enterprises: The Challenge of Institutionalization in a Neoliberal Era. Nonprofit Policy Forum 2016, 7, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOS Nieuws. Tweede Kamer Wil Sociale Werkvoorziening Nieuw Leven Inblazen. 2021. Available online: https://nos.nl/artikel/2367048-tweede-kamer-wil-sociale-werkvoorziening-nieuw-leven-inblazen (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Latapí Agudelo, M.; Jóhannsdóttir, L.; Davídsdóttir, B. A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.; Kramer, M. The Big Idea: Creating Shared Value. How to Reinvent Capitalism—And Unleash a Wave of Innovation and Growth. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, A.; Palazzo, G.; Spence, L.; Matten, D. Contesting the Value of “Creating Shared Value”. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 56, 130–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrier, H. Ethical consumption practices: Co-production of self-expression and social recognition. J. Consum. Behav. 2007, 6, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.A.; Murray, D.L. Ethical Consumption, Values Convergence/Divergence and Community Development. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2013, 26, 351–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Moosmayer, D.C. When Guilt is Not Enough: Interdependent Self-Construal as Moderator of the Relationship Between Guilt and Ethical Consumption in a Confucian Context. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 161, 551–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R. The taste for green: The possibilities and dynamics of status differentiation through “green” consumption. Poetics 2013, 41, 294–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Kim, H. Are Ethical Consumers Happy? Effects of Ethical Consumers’ Motivations Based on Empathy Versus Self-orientation on Their Happiness. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, A.; Woodall, T. Everything Flows: A Pragmatist Perspective of Trade-Offs and Value in Ethical Consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 893–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Chen, C.-W.; Tung, Y.-C. Exploring the Consumer Behavior of Intention to Purchase Green Products in Belt and Road Countries: An Empirical Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, N.; Salzmann, O.; Steger, U.; Ionescu-Somers, A. Moving Business/Industry Towards Sustainable Consumption: The role of NGOs. Eur. Manag. J. 2002, 20, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.; Peloza, J. How does corporate social responsibility create value for consumers? J. Consum. Mark. 2011, 28, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y.; Bernarda, G.; Smith, A.; Papadakos, T. Value Proposition Design: How to Create Products and Services Customers Want; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hyllegard, K.H.; Yan, R.N.; Ogle, J.P.; Lee, K.H. Socially Responsible Labeling: The Impact of Hang Tags on Consumers’ Attitudes and Patronage Intentions Toward an Apparel Brand. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2012, 30, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorek, S.; Lucas, R. Towards Sustainable Market Strategies: A Case Study on Eco Textiles and Green Power. 2003. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/49107 (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Solomon, M.; Marshall, G.; Stuart, E.; Mitchell, V.; Barnes, B. Marketing. Real People, Real Decisions; Second European; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, G.F.; Beck, J.T.; Henderson, C.M.; Palmatier, R.W. Building, measuring, and profiting from customer loyalty. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 790–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schösler, H.; de Boer, J.; Boersema, J.J. The Organic Food Philosophy: A Qualitative Exploration of the Practices, Values, and Beliefs of Dutch Organic Consumers Within a Cultural-Historical Frame. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2013, 26, 439–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerzema, J.; DÁntonio, M. Spend Shift: How the Post-Crisis Values Revolution Is Changing the Way We Buy, Sell, and Live, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- SB Insight. Official Report 2022 Sustainable Brand Index; SB Insight: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- B-Open, Market Response. Monitor Merk & Maatschappij 2021. 2021. Available online: https://marketresponse.nl/resources/download-trendrapport-monitor-merk-maatschappij-2021/ (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- SB Insight. Sustainable Brand Index B2C; SB Insight: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez-Cacho, P.; Leyva-Díaz, J.C.; Sánchez-Molina, J.; van der Gun, R. Plastics and sustainable purchase decisions in a circular economy: The case of Dutch food industry. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L.M. Exploring attitude–behaviour gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; van Doorn, J. Segmenting Consumers According to Their Purchase of Products with Organic, Fair-Trade, and Health Labels. J. Mark. Behav. 2016, 2, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).