Determinants and Impacts of Quality Attributes on Guest Perceptions in Norwegian Green Hotels

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- RQ 1: What are guests’ predominant themes and concepts about their experiences with green hotels in Norway?

- -

- RQ 2: Which main themes and concepts lead to guest satisfaction and dissatisfaction?

- -

- RQ 3: What are the main narratives or preferences shared by the different types of guests, gender, and regions?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability in the Hospitality Industry

2.2. Green Service Quality and Service Quality Attributes

2.3. Online Reviews in the Hospitality Domain

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Method

3.2. Data Collection and Sample

3.3. Data Treatment

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Distribution

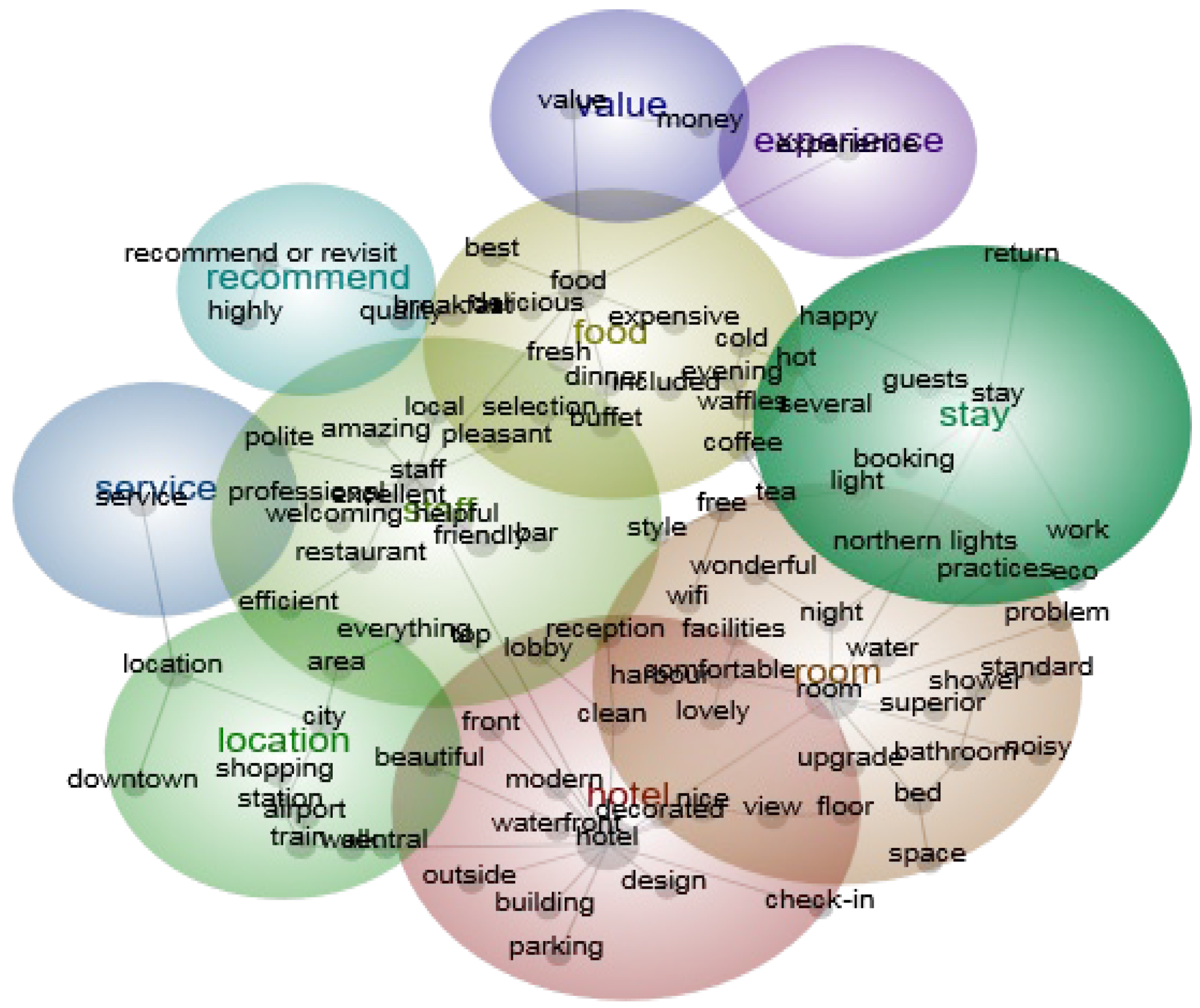

4.2. Concept Analysis

4.2.1. Hotel Theme

4.2.2. Room Theme

4.2.3. Food Theme

4.2.4. Location Theme

4.2.5. Staff Theme

4.2.6. Stay Theme

4.2.7. Service Theme

4.2.8. Recommend Theme

4.2.9. Value Theme

4.3. Satisfaction or Dissatisfaction: Analysis

4.4. Experiences and Preferences of Guests

4.4.1. Couple Guests

4.4.2. Business Guests

4.4.3. Family Guests

4.4.4. Friend Guests

4.4.5. Solo Guests

4.5. Evaluation of Norwegian Green Hotels Experiences by Gender

4.6. Evaluation of Norwegian Green Hotel Experiences by Guest Origins

4.6.1. European Guests

4.6.2. American Guests

4.6.3. Australian Guests

4.6.4. Asian Guests

4.6.5. African Guests

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Managerial Implications

5.4. Limitations and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdou, A.H.; Hassan, T.H.; El Dief, M.M. A Description of Green Hotel Practices and Their Role in Achieving Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTTC. Travel & Tourism Economic Impact 2021: Global Economic Impact & Trends 2021. WTTC, June 2021. p. 29. Available online: https://wttc.org/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/2021/Global%20Economic%20Impact%20and%20Trends%202021.pdf?ver=2021-07-01-114957-177 (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- WTTC. Economic Impact Reports. 2021. Available online: https://wttc.org/research/economic-impact (accessed on 16 July 2021).

- Statista. Norway: Number of Accommodation Enterprises, by Sector. En. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/861981/number-of-accommodation-enterprises-in-Norway-by-sector/ (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.-P.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Li, X.; Jai, T.-M. Hotel guests’ perception of best green practices: A content analysis of online reviews. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 18, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Reynolds, D.; Svaren, S. How “green” are North American hotels? An exploration of low-cost adoption practices. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A.; Ali, F. Why should hotels go green? Insights from guests experience in green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, X.; Jai, T.-M. The impact of green experience on customer satisfaction: Evidence from TripAdvisor. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1340–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Park, J.; Chi, C.G.-Q. Consequences of “greenwashing”: Consumers’ reactions to hotels’ green initiatives. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1054–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graci, S.; Kuehnel, J. How to Increase Your Bottom Line by Going Green; Green Hotels & Responsible Tourism Initiative: Norwalk, CT, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fauziah, D.; Noralisa, I.; Ahmad, I.; Mohamad, I. Green practices in hotel industry: Factors influencing the implementation. J. Tour. Hosp. Culin. Arts 2017, 9, 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Sanhaji, Z. Green Initiatives in the U.S. Lodging Industry. Available online: https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/70676 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Green Hotels Association. Why Should Hotels Be Green? 2022. Available online: http://greenhotels.com/index.php (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- TripAdvisor. TripAdvisor GreenLeaders (TM) Program Highlights Eco-Friendly Hotels To Help Guests Plan Greener Trips. Available online: https://www.tripadvisor.com/GreenLeaders (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Teng, Y.-M.; Wu, K.-S.; Liu, H.-H. Integrating Altruism and the Theory of Planned Behavior to Predict Patronage Intention of a Green Hotel. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 39, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graci, S.; Dodds, R. Why Go Green? The Business Case for Environmental Commitment in the Canadian Hotel Industry. Anatolia Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2008, 19, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.-T.J.; Lee, J.-S.; Sheu, C. Are lodging customers ready to go green? An examination of attitudes, demographics, and eco-friendly intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-B.; Kim, D.-Y. The Effects of Message Framing and Source Credibility on Green Messages in Hotels. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 2014, 55, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yoon, H. Customer retention in the eco-friendly hotel sector: Examining the diverse processes of post-purchase decision-making. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1095–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olorunsola, V.O.; Saydam, M.B.; Arasli, H.; Sulu, D. Guest service experience in eco-centric hotels: A content analysis. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Stepchenkova, S. User-Generated Content as a Research Mode in Tourism and Hospitality Applications: Topics, Methods, and Software. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 24, 119–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Soto, E.; Armas-Cruz, Y.; Morini-Marrero, S.; Ramos-Henríquez, J.M. Hotel guests’ perceptions of environmental friendly practices in social media. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 78, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Jai, T.-M.; Li, X. Examining green reviews on TripAdvisor: Comparison between resort/luxury hotels and business/economy hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2020, 21, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, R.A.; Méxas, M.P.; Meiriño, M.J. Sustainability and hotel business: Criteria for holistic, integrated and participative development. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, E.E. Sustainable hotel business practices. J. Retail. Leis. Prop. 2005, 5, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, R.A.; Méxas, M.P.; Meiriño, M.J.; Sampaio, M.C.; Costa, H.G. Criteria for assessing a sustainable hotel business. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Barber, N.; Kim, D.-K. Sustainability research in the hotel industry: Past, present, and future. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 576–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janković, S.; Krivačić, D. Environmental accounting as perspective for hotel sustainability: Literature review. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 20, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Maksoud, A.; Kamel, H.; Elbanna, S. Investigating relationships between stakeholders’ pressure, eco-control systems and hotel performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 59, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Leung, A.Y. A preliminary study on potential of developing shower/laundry wastewater reclamation and reuse system. Chemosphere 2003, 52, 1451–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimara, E.; Manganari, E.; Skuras, D. Don’t change my towels please: Factors influencing participation in towel reuse programs. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melissen, F.; Koens, K.; Brinkman, M.; Smit, B. Sustainable development in the accommodation sector: A social dilemma perspective. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, S. Going green: The evolution of micro-business environmental practices. Bus. Ethic A Eur. Rev. 2012, 21, 220–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepoutre, J. Proactive Environmental Strategies in Small Businesses: Resources, Institutions and Dynamic Capabilities. Ph.D. Thesis, Ghent University, Gent, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. The Debate over Doing Good: Corporate Social Performance, Strategic Marketing Levers, and Firm-Idiosyncratic Risk. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Gursoy, D. Influence of sustainable hospitality supply chain management on customers’ attitudes and behaviors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 49, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyilasy, G.; Gangadharbatla, H.; Paladino, A. Perceived Greenwashing: The Interactive Effects of Green Advertising and Corporate Environmental Performance on Consumer Reactions. J. Bus. Ethic 2014, 125, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton. Travel With Purpose: Hilton 2020 Environmental, Social and Governance (Esg) Report. 2020, p. 72. Available online: https://cr.hilton.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Hilton-2020-ESG-Report.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Statista. Number of Hotels Worldwide. 2018. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1092502/number-of-hotels-worldwide/ (accessed on 4 June 2022).

- Statista. Topic: Hotels in Norway. 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/6794/hotels-in-norway/ (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Han, X.; Chan, K. Perception of Green Hotels Among Tourists in Hong Kong: An Exploratory Study. Serv. Mark. Q. 2013, 34, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. The Investigation of Green Best Practices for Hotels in Taiwan. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 57, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Kasliwal, N. Going Green: A Study on Consumer Perception and Willingness to Pay towards Green Attributes of Hotels. Int. J. Emerg. Res. Manag. Technol. 2017, 6, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C. Sustainable Tourism and the Touristic Ecological Footprint. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2002, 4, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C. Sustainable tourism as an adaptive paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 850–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezan, O.; Millar, M.; Raab, C. Sustainable Hotel Practices and Guest Satisfaction Levels. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2014, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.-T.; Sheu, C. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Mattila, A.S.; Lee, S. A meta-analysis of behavioral intentions for environment-friendly initiatives in hospitality research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 54, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.H.; Stein, L.; Heo, C.Y.; Lee, S. Consumers’ willingness to pay for green initiatives of the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chang, C. Towards green trust: The influences of green perceived quality, green perceived risk, and green satisfaction. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedera, D.; Lokuge, S.; Atapattu, M.; Gretzel, U. Likes—The key to my happiness: The moderating effect of social influence on travel experience. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-C.; Cheng, C.-C. What drives green advocacy? A case study of leisure farms in Taiwan. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 33, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-C.; Ai, C.-H.; Cheng, C.-C. Synthesizing the effects of green experiential quality, green equity, green image and green experiential satisfaction on green switching intention. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2080–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Hsu, L.-T.; Han, H.; Kim, Y. Understanding how consumers view green hotels: How a hotel’s green image can influence behavioural intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinot, E.; Giannelloni, J. Do hotels’ “green” attributes contribute to customer satisfaction? J. Serv. Mark. 2010, 24, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. In Handbook of the Fundamentals of Financial Decision Making: Part I. World Scientific; Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2013; pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, R.; Thyne, M.; Davies, S. An investigation into customer satisfaction levels in the budget accommodation sector in Scotland: A case study of backpacker tourists and the Scottish Youth Hostels Association. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassinis, G.I.; Soteriou, A.C. Greening the service profit chain: The impact of environmental management practices. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2003, 12, 386–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-H.; Cheng, C.-C. Less is more: A new insight for measuring service quality of green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 68, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, B.; Stevens, P.; Wullaert, C.; Patton, M.; Yokoyama, F. Lodgserv: A Service Quality Index for the Lodging Industry. Hosp. Res. J. 1990, 14, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, A. Socio-Environmentally Responsible Hotel Business: Do Tourists to Penang Island, Malaysia Care? J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2004, 11, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaktola, K.; Jauhari, V. Exploring consumer attitude and behaviour towards green practices in the lodging industry in India. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slevitch, L.; Mathe, K.; Karpova, E.; Scott-Halsell, S. “Green” attributes and customer satisfaction: Optimization of resource allocation and performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 802–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Mattila, A.S. Improving consumer satisfaction in green hotels: The roles of perceived warmth, perceived competence, and CSR motive. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 42, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P. Customer loyalty: Exploring its antecedents from a green marketing perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 896–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdt, S.-O.; Wagner, E.; Schewe, G. The relationship between sustainability and customer satisfaction in hospitality: An explorative investigation using eWOM as a data source. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuckert, M.; Liu, X.; Law, R. Hospitality and Tourism Online Reviews: Recent Trends and Future Directions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 608–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Chung, N.; Xiang, Z.; Koo, C. Assessing the Impact of Textual Content Concreteness on Helpfulness in Online Travel Reviews. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Yoo, K.H. Use and impact of online travel reviews. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2008; pp. 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Tian, X.; Tao, R.; Zhang, W.; Yan, G.; Akula, V. Application of social media analytics: A case of analyzing online hotel reviews. Online Inf. Rev. 2017, 41, 921–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Han, H.; Koo, C. Adoption of travel information in user-generated content on social media: The moderating effect of social presence. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2015, 34, 902–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’connor, P. User-generated content and travel: A case study on Tripadvisor. com. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2008; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2008; pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Aakash, A.; Aggarwal, A.G. Assessment of Hotel Performance and Guest Satisfaction through eWOM: Big Data for Better Insights. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2022, 23, 317–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantallops, A.S.; Salvi, F. New consumer behavior: A review of research on eWOM and hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Law, R.; Gu, B.; Chen, W. The influence of user-generated content on traveler behavior: An empirical investigation on the effects of e-word-of-mouth to hotel online bookings. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, I.E.; Seegers, D. Tried and tested: The impact of online hotel reviews on consumer consideration. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.; Law, R.; Van Hoof, H.; Buhalis, D. Social Media in Tourism and Hospitality: A Literature Review. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilashi, M.; Mardani, A.; Liao, H.; Ahmadi, H.; Manaf, A.A.; Almukadi, W. A Hybrid Method with TOPSIS and Machine Learning Techniques for Sustainable Development of Green Hotels Considering Online Reviews. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arici, H.E.; Arıcı, N.C.; Altinay, L. The use of big data analytics to discover customers’ perceptions of and satisfaction with green hotel service quality. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 26, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, A.; Rita, P.; Oliveira, C.; Oliveira, F. Airline passengers’ perceptions of service quality: Themes in online reviews. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 855–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinay, L.; Paraskevas, A.; Ali, F. Planning Research in Hospitality and Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sulu, D.; Arasli, H.; Saydam, M.B. Air-Travelers’ Perceptions of Service Quality during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from Tripadvisor Sites. Sustainability 2021, 14, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasli, H.; Saydam, M.B.; Gunay, T.; Jafari, K. Key attributes of Muslim-friendly hotels’ service quality: Voices from booking.com. J. Islam. Mark. 2023, 14, 106–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Stepchenkova, S. Ecotourism experiences reported online: Classification of satisfaction attributes. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, H.; Chiu, W.; Won, D. The Voice from Users of Running Applications: An Analysis of Online Reviews Using Leximancer. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olorunsola, V.O.; Saydam, M.B.; Lasisi, T.T.; Ozturen, A. Exploring tourists’ experiences when visiting Petra archaeological heritage site: Voices from TripAdvisor. Consum. Behav. Tour. Hosp. 2023, 18, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayfuddin, A. When green practices affect business performance: An investigation into California’s hotel industry. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2022, 36, 154–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, H.; Brochado, A.; Troilo, M.; Mohsin, A. Wellness comes in salty water: Thalassotherapy spas and service level of satisfaction. Int. J. Spa Wellness 2022, 5, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, A.; Troilo, M.; Shah, A. Airbnb customer experience: Evidence of convergence across three countries. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 63, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.Y.; Wall, G.; Pearce, P.L. Shopping experiences: International tourists in Beijing’s silk market. Tour. Manag. 2014, 41, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saydam, M.B.; Olorunsola, V.O.; Rezapouraghdam, H. Passengers’ service perceptions emerging from user-generated content during the pandemic: The case of leading low-cost carriers. TQM J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasli, H.; Furunes, T.; Jafari, K.; Saydam, M.B.; Degirmencioglu, Z. Hearing the Voices of Wingless Angels: A Critical Content Analysis of Nurses’ COVID-19 Experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, C.; Wu, B.; Morrison, A.M.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.-C. Travel blogs on China as a destination image formation agent: A qualitative analysis using Leximancer. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambo, T.H.; Ersoy, M.; Auwal, A.M.; Olorunsola, V.O.; Saydam, M.B. Office of the citizen: A qualitative analysis of Twitter activity during the Lekki shooting in Nigeria’s #EndSARS protests. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2022, 25, 2246–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angus, D.; Rintel, S.; Wiles, J. Making sense of big text: A visual-first approach for analysing text data using Leximancer and Discursis. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2013, 16, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olorunsola, V.O.; Saydam, M.B.; Lasisi, T.T.; Eluwole, K.K. Customer experience management in capsule hotels: A content analysis of guest online review. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnawas, I.; Hemsley-Brown, J. Examining the key dimensions of customer experience quality in the hotel industry. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 833–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Sun, K.-A.; Wu, L.; Xiao, Q. A Moderating Role of Green Practices on the Relationship between Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction: Chinese Hotel Context. J. China Tour. Res. 2018, 14, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Impact of hotel-restaurant image and quality of physical-environment, service, and food on satisfaction and intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 63, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandampully, J.; Suhartanto, D. The Role of Customer Satisfaction and Image in Gaining Customer Loyalty in the Hotel Industry. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2003, 10, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Chandra, B. Hotel Guest’s Perception and Choice Dynamics for Green Hotel Attribute: A Mix Method Approach. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 77601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, Y. An investigation of green hotel customers’ decision formation: Developing an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimri, R.; Patiar, A.; Kensbock, S. A green step forward: Eliciting consumers’ purchasing decisions regarding green hotel accommodation in Australia. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 33, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, M.; Mayer, K.J.; Baloglu, S. Importance of Green Hotel Attributes to Business and Leisure Travelers. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2012, 21, 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam Malik, S.; Akhtar, F.; Raziq, M.M.; Ahmad, M. Measuring service quality perceptions of customers in the hotel industry of Pakistan. Total. Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2020, 31, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.; Jang, S. Effects of restaurant green practices: Which practices are important and effective? Purdue Univ. Main Campus 2010, 33, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M.A.; Davis, E.A.; Weaver, P.A. Eco-friendly Attitudes, Barriers to Participation, and Differences in Behavior at Green Hotels. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 2014, 55, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Jai, T.-M.; Li, X. Guests’ perceptions of green hotel practices and management responses on TripAdvisor. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2016, 7, 182–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertella, G. Northern lights chase tours: Experiences from northern Norway. J. North. Stud. 2013, 7, 95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Brochado, A. Nature-based experiences in tree houses: Guests’ online reviews. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, A.; Troilo, M.; Rodrigues, H.; Oliveira-Brochado, F. Dimensions of wine hotel experiences shared online. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2020, 32, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, M.; Baloglu, S. A Green Room Experience: A Comparison of Business & Leisure Travelers’ Preferences. Hosp. Manag. 2009. Available online: https://repository.usfca.edu/hosp/10/ (accessed on 28 January 2023).

- Moise, M.S.; Gil-Saura, I.; Molina, M.E.R. The importance of green practices for hotel guests: Does gender matter? Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2021, 34, 3508–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L.; Wu, M.-Y. Tourists’ Evaluation of a Romantic Themed Attraction: Expressive and instrumental issues. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Mandal, P. Traveler preferences from online reviews: Role of travel goals, class and culture. Tour. Manag. 2020, 80, 104108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Travel and Tourism in Norway. Eng. Statista Dossier on Travel and Tourism in Norway. 2021, p. 45. Available online: https://www.statista.com/study/48134/travel-and-tourism-in-norway/ (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Hoare, R.J.; Butcher, K. Do Chinese cultural values affect customer satisfaction/loyalty? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 20, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Peng, N. Recommending green hotels to travel agencies’ customers. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Ngniatedema, T.; Li, S. A cross-country comparison of green initiatives, green performance and financial performance. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 1008–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Green Level Badges | Evaluation Criteria |

|---|---|

| Platinum | Must meet up 60% or greater score on green practices survey evaluation |

| Gold | Must meet up 50% score on green practices survey evaluation |

| Silver | Must meet up 40% score on green practices survey evaluation |

| Bronze | Must meet minimum green practices and 30% score on green practices evaluation survey |

| Green Partner | Meets minimum green practices requirement |

| Hotel Name | Star Ratings | Green Leaders Level | Total Comments | Sample Size | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 4.5 | Gold | 2482 | 248 | Tromso |

| B | 4.5 | Platinum | 2006 | 201 | Tromso |

| C | 4.5 | Silver | 1259 | 126 | Tromso |

| D | 4.0 | Silver | 2249 | 225 | Trondheim |

| E | 4.0 | Silver | 2168 | 217 | Bergen |

| F | 4.0 | Silver | 1191 | 119 | Trondheim |

| G | 4.0 | Silver | 1684 | 168 | Oslo |

| H | 4.0 | Gold | 1147 | 115 | Kristiansand |

| I | 4.0 | Silver | 1562 | 156 | Oslo |

| Total | - | - | 15,748 | 1575 | - |

| Distribution | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 629 | 39.9 |

| Male | 850 | 54 | |

| Unknown | 96 | 6.1 | |

| Origin | Europe | 1119 | 71.1 |

| America | 244 | 15.5 | |

| Asia | 115 | 7.3 | |

| Australia | 81 | 5.1 | |

| Africa | 16 | 1 |

| Variable | Reviewers | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Satisfaction | 1 | 50 | 3.2 |

| 2 | 179 | 11.4 | |

| 4 | 579 | 36.8 | |

| 5 | 767 | 48.7 | |

| Guests Profile | Business | 419 | 26.6 |

| Couple | 603 | 38.3 | |

| Family | 301 | 19.1 | |

| Friends | 139 | 8.8 | |

| Solo | 113 | 7.3 | |

| Total | 1575 | 100.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ali, U.; Arasli, H.; Arasli, F.; Saydam, M.B.; Capkiner, E.; Aksoy, E.; Atai, G. Determinants and Impacts of Quality Attributes on Guest Perceptions in Norwegian Green Hotels. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5512. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065512

Ali U, Arasli H, Arasli F, Saydam MB, Capkiner E, Aksoy E, Atai G. Determinants and Impacts of Quality Attributes on Guest Perceptions in Norwegian Green Hotels. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):5512. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065512

Chicago/Turabian StyleAli, Usman, Huseyin Arasli, Furkan Arasli, Mehmet Bahri Saydam, Emel Capkiner, Emel Aksoy, and Guzide Atai. 2023. "Determinants and Impacts of Quality Attributes on Guest Perceptions in Norwegian Green Hotels" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 5512. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065512

APA StyleAli, U., Arasli, H., Arasli, F., Saydam, M. B., Capkiner, E., Aksoy, E., & Atai, G. (2023). Determinants and Impacts of Quality Attributes on Guest Perceptions in Norwegian Green Hotels. Sustainability, 15(6), 5512. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065512