Abstract

The introduction of social media in the restaurant sector has changed the manner in which customers communicate with businesses. Social media marketing activities (SMMAs), such as customization, entertainment, trendiness, and interaction may have a substantial impact on followers’ perceived value and consumer behavioral intentions. Therefore, this research aims to investigate the impact of SMMAs on restaurant social media followers’ purchase intentions (PUR), willingness to pay a premium price (WPP), and e-WoM. Additionally, drawing on the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) model, we seek to explore the mediation impact of perceived value (PV) in these relationships. To achieve this, an online questionnaire was developed for data collection from a convenience sample of casual-dining restaurant followers in Saudi Arabia. A sample of 433 social media followers was studied using PLS-SEM for testing the study hypotheses. The findings highlighted the significant positive impact of SMMAs on followers’ PV, PUR, e-WoM, and WPP. Further, PV partially significantly mediated the relationship between SMMAs and their consequences. Consequently, providing relevant, up-to-date, and entertaining content; responsiveness to customer needs and feedback; and positive brand engagement significantly contributed to enhancing restaurant followers’ perceived value, which sequentially improves their purchase intention, boosts positive e-WoM, and promotes the possibility of WPP for restaurant products and services. This research provides restaurant operators and marketers with valuable insights into how SMMAs influence followers’ behavioral intentions and enhances their understanding of how perceived value can be utilized to capitalize on the benefits of social media.

1. Introduction

Social media marketing has become an increasingly important part of modern marketing strategies. In recent years, businesses have been leveraging the power of social media to reach new clients, interact with existing ones, and increase awareness of the brand []. Social media platforms offer businesses with a variety of ways to interact with their target audience. Through these platforms, businesses can create content that is tailored to their target audience and share it with their followers []. Additionally, businesses can use social media to run targeted ads that are tailored to specific audiences and assess their campaign’s success [,]. Businesses can also use social media to gain valuable insights into customer behavior and preferences for future marketing campaigns []. Overall, SMM has become an integral part for businesses looking to reach new customers and build relationships with existing ones [].

Customer behavioral intentions are important in understanding consumer behavior and predicting future purchasing decisions [,]. PUR, WPP, and e-WoM are three measurements of customer behavioral intentions that can be used to gain insight into consumer behavior []. Purchase intention is a concept that refers to the likelihood of a consumer making a purchase. It is based on the idea that consumers go through a process of decision-making before they make a purchase [,]. This process includes gathering information, evaluating alternatives, and making a decision. Factors such as price, quality, convenience, and availability can influence purchase intention []. Further, e-WoM is an important factor in customer behavior as it provides insight into what other customers think about the product or service []. This can be measured by analyzing online reviews and comments from customers who have already purchased the product or service []. The WPP indicates how much a customer is willing to spend over the market price for services or products [,]

A perceived value (PV) is what the customer thinks a product or service is worth based on the benefits it provides compared to its cost []. It is determined by factors such as quality, brand, features, and customer service []. When customers recognize a greater value from a service or product, they are more inclined to purchase it and even pay an increased cost for it as well as interact in e-WoM activities, such as discussing their experiences with others on social media platforms [,,].

Prior studies have documented the influence of SMM on PUR, WPP, e-WoM, and PV. Findings have indicated that customers are significantly affected by social media marketing activities, with higher levels of engagement leading to greater PUR, WPP, e-WoM, and PV i.e., [,,]. Companies that actively engage in social media marketing have been seen to benefit from higher levels of customer loyalty, due to their increased perceived value among customers. Additionally, effective social media marketing can help businesses better engage with a larger target audience, while also helping to optimize their marketing campaigns to maximize their return on investment [,].

Even though numerous scholars have been interested in investigating the link between SMMAs and customer behavioral intentions in terms of PUR, WPP, and e-WoM in various settings, the links between these variables in the casual dining restaurant industry setting, specifically in developing countries, is still inadequate. The need to gain an in-depth understanding of how SMMAs can alter consumers’ perception of value, PUR, WPP, and e-WoM among restaurant social media followers is crucial. This is particularly relevant as SMMAs have become increasingly important for restaurants, and understanding their impact on customer behavior is substantial for restaurant operators in making informed decisions in marketing investments. Further, the findings of earlier studies were inconsistent. While some studies have illustrated that SMMAs significantly affected customer behavioral intentions, others have indicated that the influence of SMMAs or some of them may not have been significant i.e., [,,]. These findings have varied, indicating more research is required to better understand the associations between these variables. Furthermore, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, very few studies have examined the mediating effect of PV on the SMMAs-PUR, SMMAs-WPP, and SMMAs-e-WoM relationships in the restaurant context. Accordingly, to narrow the gap in the restaurant industry context, this study aims to empirically investigate the influence of SMMAs on PV, PUR, WPP, and e-WoM among restaurant social media followers. Further, the study will aim to examine the impact of PV on PUR, WPP, and e-WoM. Additionally, and drawing on the stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) model, the study seeks to explore the potential mediating role of PV in these relationships.

This study focuses on followers of casual dining restaurants, which are recognized as restaurants that offer a combination of fast food and fine dining as well as serve food at a moderate price with a casual atmosphere []. The casual dining market has seen a steady rise in market shares in recent years []. Casual dining restaurant marketers use social networking sites to boost engagement on social media []. They are taking advantage of social media platforms to broaden their exposure, reach their desired target customers (most often young people), and create more sales. This segment of social media users is likely to be more engaged and have a strong presence in the digital world [,]. Accordingly, it is easy to solicit their opinion for research purposes. This study is important for the restaurant industry because it provides insight into how SMMAs can influence PV, PUR, WPP, and e-WoM. The use of SMM by restaurants has become increasingly effective as a way of reaching their target market and establishing brand awareness. By understanding the impact of SMMAs on these factors, restaurants can better tailor their strategies to enhance their relationship with their customers, increase sales, and remain competitive in the market.

This study has greatly enriched SMM literature by empirically investigating a theoretical model; using the S-O-R model; including customized, entertaining, trendy, and interactive social media marketing as key factors (stimuli) in driving followers’ PV (organism) and contributing to encouraging PUR; promoting a WPP; and enhancing e-WoM (response) among restaurant social media followers. Further, PV has never previously been examined as a mediator in the relationships between SMMAs-PUR, SMMAs-WPP, and SMMAs-e-WoM in the restaurant industry context, particularly in developing countries such as Saudi Arabia. Additionally, from a practical point of view, restaurant operators and marketers can use the findings of this study as a guide to shape their social media marketing strategies in order to improve perceived value and enhance PUR, WPP, and e-WoM. Finally, by using the conclusions from this research, restaurants can explore how their SMMAs affect directly and indirectly (via PV) consumer behavioral intentions, resulting in long-term customer relationships, increased sales, and remaining competitive in the market.

This study is organized in a systematic manner. Following the introduction, Section 2 explores related literature and formulates hypotheses involving SMMAs, PV, PUR, WPP, and e-WoM. Section 3 presents the methodology, sample, and statistical analysis. Section 4 examines the assessment of the measurement model, analysis of the structural model, and hypotheses testing results. Section 5 and Section 6 discuss the results and implications, both practically and theoretically. Finally, Section 6 presents the study’s limitations and scope for future research.

2. Theoretical Background and the Development of Hypotheses

2.1. Social Media Marketing (SMM) and Its Related Activities (SMMAs)

Generally, social media refers to a group of online-based applications, platforms, or media that facilitate interaction, collaboration, or sharing of content []. The platforms for social media can include social networking sites (SNSs), blogs, and virtual social worlds. Also, it may include integration with a variety of sites via web links, users’ ratings and reviews, referrals, recommendations, forums, user-generated content, and communities [,]. The majority of these platforms are widely used for social media marketing (SMM) due to their perceived ability to boost revenue []. The term SMM has been defined by many scholars. For instance, Weinberg ([], p.3) defined SMM as “The process that empowers individuals to promote their websites, products, or services through online social channels and tap into a much larger community that may not have been available via traditional channels”. Barker et al. [] conceptualized SMM as the online community usage of blogs and other collaborative online media to market, sell, publicize, and serve customers. Others have described it as the practices that employ social media channels and technologies for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging products and services that add value for the organization’s stakeholders [].

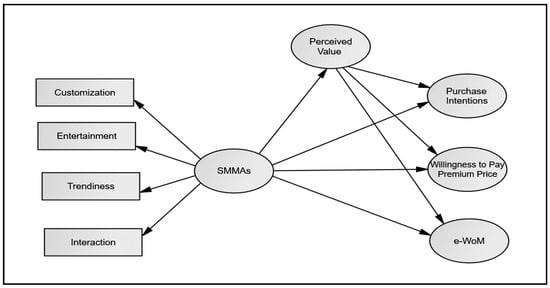

Numerous studies with different authors have examined the components of SMM in different contexts. For instance, Kim and Ko [] in the luxury brands context as well as Seo et al. [] in the airline industry context classified SMM activities into five components, namely interaction, customization, entertainment, trendiness, and e-WoM. Further, in the assurance services setting, Sano [] utilized customization, interaction, perceived risk, and trendiness as dimensions of SMM. Yadav and Rahman [], in their empirical study conducted to explore the influence of SMM on consumer loyalty to the e-commerce industry, categorized SMM activities into five dimensions, including interactivity, informativeness, WoM, trendiness, and personalization. Meanwhile, in the luxury cosmetic brands context, SMM was conceptualized by Cheung et al. [] as a multidimensional variable that consists of four factors including entertainment, customization, interaction, and trendiness. They omitted e-WoM because it was regarded as a behavioral outcome resulting from SMM adoption. In agreement with Cheung et al. [], as e-WoM is considered a behavioral outcome, this study will use the following four dimensions of SMMAs: customization, entertainment, interaction, and trendiness, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework of the study.

In social media marketing, customization (CUS) relies on contacting each user individually, which is a big difference from conventional advertising. Customizing products or services refers to tailoring them to meet and suit customers’ individual preferences []. By utilizing social media technologies, marketers can customize their messages to engage consumers in a personal conversation, create value for a particular customer, and contribute to sustaining the customer-company relationship []. The CUS is regarded as a strategy aimed at generating positive perceived control and enhancing consumer satisfaction [,]. Among SMMAs, entertainment help to evoke customers’ positive emotions, facilitates participation, and creates a desire to use the platform repeatedly. Marketers use social media channels to generate fun and entertaining experiences for customers using, for example, images, videos, and games. SMM strategies are increasingly using entertaining content to build consumer awareness and loyalty behavioral intentions [,,]. It could be noticed that interaction is considered one of the most important activities of SMM. Interaction allows customers the opportunity to share information, have two-way communication, exchange ideas, and converse with like-minded people about specific products, services, or brands. Based on these interactions, company-customer relationships are changing fundamentally, and user-generated content (UGC) in social networks is also evolving [,]. Additionally, through interaction, the company ensures consumers are highly aware of the benefits of the brand and the attributes of its products []. In SMM, an organization’s trendiness is referred to its ability to communicate the latest, most current, and most relevant information about its services and products []. The information consumers obtain from social media is more likely to be trusted than that acquired from advertising and promotion activities []. Through trendiness, companies provide their current and potential customers with the newest knowledge and information, as well as innovative ideas about the products, services, and promotions they offer, which help consumers make a well-thought-out purchase decision [].

2.2. Perceived Value (PV)

Since its appearance in 1980, perceived value (PV) has received considerable attention from academics and professionals []. The Marketing Science Institute’s research agenda for 2006–2008 included the definition of PV []. Many scholars have regarded the use of PV in business marketing as a key metric. Subsequently, marketers have been paying increasing attention to PV because of the growing number of value-conscious consumers []. As stated by Wang et al. [], the concept’s significance lies in its psychological and economic components, and its ability to attain businesses’ competitive advantages. The customer PV is widely defined as “the consumer’s overall assessment of the utility of a product based on perceptions of what is received and what is given” ([], p. 14). It simply refers to the comparison of what the consumer gave and what he or she gained. The previous definition of PV has been criticized by some authors as too narrow. They have described PV as a multidimensional variable that includes various dimensions such as perceived price, benefits, quality, and cost []. Roh et al. [] emphasized that PV may also encompass emotional, social, epistemic, and conditional dimensions. Moreover, El-Adly [] classified the dimensions of PV into six categories, namely, prestige value, self-gratification value, hedonistic value, transaction value, quality value, and aesthetic value.

In terms of consumer behavior, PV is the key predictor influencing customers’ preferences and behavioral intentions [,]. Companies can determine customers’ needs and preferences and improve the added value by examining the experiential value that reflects the value perceived through interactions between customers and products []. Experiential value is divided into four attributes as follows: (1) Aesthetics refers to whether the perceived service was harmonized and consistent with personal preferences; (2) Playfulness implies the pleasant feelings and sense of happiness experienced by customers during the service; (3) Customer return on investment indicates the benefits and rewards gained from the experience; (4) Service excellence results from the customer’s comparison between perceived service and the expected standard of the service and to what extent the perceived service surpassed customers’ expectations [,,].

2.3. Measurements of Customer Behavioral Intentions (CBIs)

According to the literature review, CBIs refer to what a customer intends to do after experiencing an activity []. In their earlier study, Ajzen and Fishbein revealed that CBIs are regarded as a customer’s desire to perform a specific action soon. In the marketing industry context, CBIs should be analyzed to fully understand customers’ behavior or motivation in the future []. A proper understanding and analysis of CBIs are considered essential factors for the success of service providers []. For social media marketers, it is imperative to recognize the key factors that affect the user’s intent to engage continuously on social media platforms []. Online purchase intention (online PUR), e-WoM, and WPP were widely used as measurements of customer behavioral intentions. Online purchase intention (online PUR) reflects the possibility of a customer purchasing a certain product or service based on his or her observed or predicted behavior from a particular online store or vendor in the future []. It is the consequence of a combination of elements like motivation, feeling interested in the product, and feeling confident and believing in the product quality as well as the benefits and advantages of the product and/or service [,]. Meanwhile, e-WoM was described as any negative or positive comments made by potential or existing customers about the company’s products and services that are available to many individuals and institutions through the Internet []. Maintaining a positive e-WoM reflects customer satisfaction and higher perceived value []. In addition, the WPP is also a significant positive indicator of customers’ behavioral intention toward company products and services. Basically, WPP is customers’ willingness to pay more for a product or service due to its perceived value []. This can be due to the quality of the product, its brand recognition, or other factors that make it more desirable than similar products []. Customers may also be willing to pay a premium price if they believe that the product or service will provide them with a greater benefit than what they would receive from a cheaper alternative. When customers are willing to pay a price premium, they are more likely to remain loyal to a service provider and are less sensitive to price changes [,].

2.4. The Relationship between SMMAs and PUR, WPP, and e-WoM

Over the past few years, an increase in the use of SMMAs by organizations targeting consumer markets has been mentioned. As these practices become more commonplace, research has been conducted to understand the relationship between SMMAs and customer behavioral intentions [,,]. Studies suggest that consumer engagement with social media marketing activities positively impacts consumer intentions such as purchase intentions, brand loyalty, and WoM. For example, a study of 375 students from Yüzüncü Yil University, Turkey, found that SMM significantly positively affected e-WoM and brand loyalty []. In the coffee shop sector context, Ibrahim et al. [] concluded that SMM significantly contributed to enhancing and improving customers’ revisit intentions for coffee shops. In terms of the SMM-PUR link, scholars concluded that SMMAs significantly and positively affected customers’ purchase intentions i.e., [,]. More specifically, they demonstrated that customers who actively engaged with content on a brand’s social media page reported higher intentions to purchase products from this brand.

In the context of SMM and customers’ willingness to pay more or pay premium prices, different studies have indicated that customer engagement with social media marketing activities can have a substantial effect on consumer intention to pay more for products and services. For instance, Farzin et al. [] indicated that SMM significantly correlated with customers’ WPP for leather products sold on social networks. Furthermore, in the banking industry context, Torres et al. [] suggested that SMMAs significantly contributed to improving consumers’ WPP. Additionally, the findings of the study on a sample of 845 participants from four countries (India, China, France, and Italy) following luxury brands revealed that SMMAs significantly influence customers’ WPP [].

Similarly, concerning the link between SMMAs and e-WoM, the literature suggests that SMMAs significantly affect e-WoM. Earlier research has demonstrated that the influence of SMMAs on e-WoM is largely determined by the nature of the activities and the audience to which they are targeted [,]. Social media interaction can significantly affect e-WoM because it allows the brand to build relationships with its customers and build credibility as a trustworthy source of information [,]. Enhancing interactions with customers assists in creating positive sentiment and encourages customers to engage with the brand’s content more frequently, which can help to increase the chances of them talking about the brand. Further, the trendiness of SMM can also substantially positively impacts WoM activity []. More specifically, being aware of the product and familiar with its recent trends relatively contribute to higher levels of word-of-mouth activity. In the context of tourism industry, Andervazh et al. [] demonstrated that using social media has a higher significant contribution to improving WoM advertising for tourist destinations in Tehran (β = 0.850, p < 0.01). Hence, it could be assumed that higher engagement in social media marketing may significantly positively affect customer behavioral intentions namely, PUR, WPP, and e-WoM. Hence, we postulate that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

SMMAs have a significant positive impact on PUR.

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

SMMAs have a significant positive impact on WPP.

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

SMMAs have a significant positive impact on e-WoM.

2.5. The Relationship between SMMAs and PV

SMM and customers’ PV are closely related. The Internet and social media have changed the way businesses interact and engage with customers, shifting the focus from transactions to relationships []. Through SMM, businesses can create a personal connection with customers by responding to customer needs and providing engaging content []. This can foster customer trust, which leads to an increase in customer perceived value for the product or service [,]. The results of the empirical study carried out by Chen and Lin [] suggested that SMMAs have a considerable effect on the PV of social media users. Further, Chafidon et al. [] indicated that SMMAs highly significantly contributed to improving customers’ PV (β = 0.850, p < 0.001). More specifically, they revealed that the increased use of SMM will increase the ability of communities to acquire more information, promote customers’ PV, and enhance the desire to engage in online transactions []. Quality content, responsiveness to customer needs, contacting each user personally, and positive brand engagement significantly contribute to an increase in customer perceived value. Hence, we could assume that:

Hypothesis 4 (H4):

SMMAs have a significant positive impact on customers’ PV.

2.6. The Impact of PV on PUR, WPP, and e-WoM

Earlier studies concluded that PV is regarded as a crucial predictor of CBIs [,,,,,,,]. The literature has shown that PV significantly encouraged PUR. Higher levels of PV have been associated with greater purchase intention, as customers have shown the willingness to pay more for products with greater perceived value. Furthermore, when customers perceive greater value from a product or service, there is a greater chance of them being satisfied with their purchase, which can lead to increased customer loyalty and improving his or her purchase intention [,]. Further, perceived value can strongly influence an individual’s WPP. If an individual perceives a product or service to be of higher value, they are more likely to be willing to pay a premium price in order to acquire it [,]. In addition, perceived value can influence how likely an individual is to recommend positive word of mouth based on the perceived values associated with a particular product or service. A high perceived value will increase the likelihood of the individual recommending the product or service to their peers, leading to positive WoM. Similarly, if the perceived value is low, the individual is less likely to recommend the product or service resulting in less positive word of mouth [,,,]. As a result, we could hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 5 (H5):

PV has a significant positive impact on PUR.

Hypothesis 6 (H6):

PV has a significant positive impact on WPP.

Hypothesis 7 (H7):

PV has a significant positive impact on e-WoM.

2.7. The Mediating Effect of PV in the Relationships between SMMAs and PUR, WPP, and E-WoM

The extent to which PV impacts the relationship between SMMAs and CBIs, particularly in the context of the restaurant industry, is still limited. Some scholars have examined this relationship in non-restaurant contexts. For instance, in the e-commerce transactions context, the results of the bootstrapping technique illustrated that PV significantly partially mediated the association between SMM and PUR []. Similarly in the Indonesian airline setting, Moslehpour et al. [] concluded that SMMAs, more specifically entertainment, significantly contributed indirectly (via PV) to the enhancement of customers’ purchase intention. Further, the findings of another empirical investigation in the Iranian insurance industry context revealed that PV plays a significant intervening role in the link between SMM and customers’ participation intention []. In the tourism sector setting, Juliana et al. [] suggested that PV significantly partially mediated the influence of SMMAs on tourists’ intention to visit Banten Province (Indonesia) as a tourist destination.

In addition to the previous results, this study’s theoretical framework will be based on the S-O-R. This model is a psychological theory that explains behavior (R) as a result of the interaction between an environmental stimulus (S) and a person’s internal responses (O) [,]. The model suggests that behavior is a result of both the stimulus and the organism’s interpretation of it, which is determined by the individual’s current state, motives, knowledges, and persona []. According to this model, stimuli from SMM (S) could influence customers’ perception of value (O), which could in turn lead to greater intent to purchase, WPP, and positive e-WoM (R). Consequently, the current study will test the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 8 (H8):

PV has a significant positive mediating effect on the relationship between SMMAs and customers’ purchase intentions.

Hypothesis 9 (H9):

PV has a significant positive mediating effect on the relationship between SMMAs and customers’ willingness to pay premium prices.

Hypothesis 10 (H10):

PV has a significant positive mediating effect on the relationship between SMMAs and positive e-WoM.

This study is conceptually framed in Figure 1. According to the S-O-R model, SMMAs including customization, entertainment, trendiness, and interaction are considered independent variables (S), whereas, PUR, WPP, as well as the intention to positive e-WoM are considered dependent ones (R). To determine the indirect impact of (S) on (R), PV as an intervening variable (O) was utilized.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measures and Instrument Development

The proposed study seeks to recognize the impact of SMMAs on customers’ PUR, WPP, and intention to positively e-WoM, as well as examine the mediating effect of PV in these relationships in a sample of casual-dining restaurants in Saudi Arabia. To achieve this, an online questionnaire was developed and administered through an electronic Google form to collect relevant data from restaurant followers. Recently, the online questionnaire has been widely used for data collection due to its several advantages such as cost efficiency, time-saving, access to a larger and more diverse population, greater reliability and accuracy, control over data storage and security, as well as its potential to include multimedia content such as images or videos to help better explain the concepts being discussed, which improves the clarity and accuracy of the collected data [].

Six sections were included in the questionnaire form. Throughout the first section, information about the demographic characteristics of participants and social media usage, such as gender, age, educational level, the most popular social networking platform, and social media usage hours per day, were requested. The second part of the study investigated the views of the participants being studied regarding SMMAs. The third part pertained to determining participants’ PV. The fourth, fifth, and sixth sections measured items that related to PUR, WPP, and e-WoM, respectively.

A four-dimensional scale of SMMAs adapted from Cheung et al. [] was employed to examine the perceptions of the investigated participants toward customization (CUS), entertainment (ENT), trendiness (TRE), and interaction (INT) activities on social media. Each dimension was composed of three items. Samples of these items are “Restaurant X offers customized services through its social media”, “Utilizing the social media channels of restaurant X is exciting”, “Restaurant X’s social media content is up to date”, and “I can easily share my opinions on restaurant X’s social media”. Further, items utilized to assess PV were derived from Yang et al. [] and Ramadan et al. []. Five items composed the scale. This is an example: “The products and services of restaurant x represent excellent value for money.” Regarding the measurements of followers’ purchase intention, an adapted three-item scale developed by Emini and Zeqiri [] and adopted by Chrisniyanti and Fah [] was utilized. A sample of this scale is: “I plan to purchase restaurant products that I have seen on social media.” Further, based on Seo et al. [], we utilized a three-item scale to measure the perceptions of the investigated respondents toward electronic word-of-mouth. “I will share positive feedback about restaurant X on my social media” is one of these items. For measuring the WPP, a two-item scale adapted from Torres et al. [] was employed. “I would pay more price for restaurant x than for similar restaurants” is a sample of these items. Based on a five-point Likert scale, all study items were measured. The items associated with all study constructs are presented in Appendix A.

The questionnaire was initially created in English and then translated into the native Arabic language of the respondents. To make sure that the Arabic and English versions were the same, the questionnaire was subjected to a back-translation by two experts fluent in both languages. It was exactly the same in the original and the revised translated version. Further, to confirm the content validity of the questionnaire form, three hospitality scholars with expertise in social media marketing were kindly asked to revise the questionnaire carefully and provide feedback to ensure the relevance of the questions and test how accurate a survey instrument it would be in capturing the information that it intends to. Additionally, to ensure the questions were understandable to respondents, there were sufficient response options and the questions were not too long or confusing. A pilot study of 40 participants was conducted, and, based on their feedback, some changes in the questionnaire’s wording were adopted. As a result, the questionnaire was found to have appropriate content validity.

3.2. Sample of the Study and Data Collection

The population of interest in this study was social media users who follow and interact on casual dining restaurants’ pages on social media platforms. A convenience sampling was utilized. Restaurants were first contacted and invited via email and their social media accounts to participate in the study. Only ten restaurants (Five from Riyad, the capital of Saudi Arabia; three from Jeddah; and two from Damam) agreed to take part in this study. Secondly, participants were identified through their following of and interactions with restaurants’ pages on social media platforms (i.e., Facebook and Twitter) and contacted individually through their accounts to invite them to take part in this study. The investigated participants were provided with a link to the survey form, which they could use to submit their responses. Additionally, a message of welcome and a clear explanation of the aims of the study were included. They were also informed that taking part was voluntary and reminded to double-check and re-submit their answers once the survey was completed. During the data-gathering period of approximately eight weeks (September–November 2022), a total of 452 forms were collected. Among them, only 433 forms were analyzed.

The criteria given by Nunnally [], which suggests a 1:10 ratio of items to sample, was used to determine the appropriate sample. So, for the questions set of 25 items, having 250 participants was considered suitable. Moreover, this figure (N = 433) complied with Hair et al.’s [] suggestion of using 100–150 samples for maximum likelihood estimation and reflected Boomsma’s [] recommendation of having a minimum of 200 samples for structural equation modeling.

3.3. Data Analysis

In this study, SPSS v. 25 and SmartPLS v. 4.0.8.7 were used to analyze the data. To provide an overview of the demographic characteristics of the participants and their use of social media marketing, frequencies and percentages were calculated. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used in combination with Cronbach’s alpha to assess the construct items’ reliability and validity. The Harman single-factor test was implemented to recognize common method variance (CMV). In order to assess the convergent validity of the study, composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) were calculated. Moreover, indicators’ cross-loading and the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) were used along with the Fornell-Larcker criterion to assess the discriminant validity. The coefficient of determination (R2), and predictors’ effect size (f2) were calculated to assess the predictive ability of the structural model. The variance inflation factor (VIF) value was examined to determine multicollinearity. Finally, the hypotheses of the study were tested, and the results were judged for statistical significance through partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) with bootstrapping technique.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the Study Sample

For data analysis, the total sample size was 433 participants comprising 59.8% males (N = 259) and the others (40.8%) females. Regarding their ages, more than two-thirds (64.2%, N = 278) were aged between 20–30. With respect to educational background, the largest group of participants had a university degree (66.7%, N = 289), followed by those who had a post-graduate degree (19.6%, N = 85). The largest category of the investigated participants (71.6%, N = 310) illustrated that they spend from 3–5 h/daily on social media platforms. In terms of the most popular social media platform, Twitter followed by Facebook and Snapchat were the most popular ones, representing 33.5%, 27.7%, and 26.6%, respectively.

4.2. Common Method Variance (CMV)

To minimize the chances of CMV because of gathering data using the online questionnaire, the researchers employed anonymity, confidentiality, and honesty to encourage accurate responses. They notified respondents that their answers would be kept confidential and merely used for research purposes. Anonymity was proposed to cover potential biases, while honesty was proposed to guarantee reliable results. Furthermore, Harman’s single-factor test was used to detect CMV. According to Podsakoff et al. [], CMV may be present if most of the variance (over 50%) can be explained by a single factor. Harman’s test was implemented by using unrotated principle component exploratory factor analysis with one-factor extraction. This study did not find any issues with CMV as only one factor could account for 41.03% of the variance.

4.3. Results of Measurement Model Assessment

The initial step in assessing the measurement model required looking at the indicator loadings []. It is recommended to have an outer loading of more than 0.708 so that the construct can explain more than 50% of the indicator’s variability, which will provide satisfactory item reliability. Table 1 shows that loadings of all factors were greater than 0.70 and statistically significant. The second step was evaluating internal consistency reliability. Cronbach’s alpha and CR were both applied. In Table 1, Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.715 to 0.912, while CR scores ranged from 0.821 to 0.926. As these values exceed Hair et al. []’s 0.70 threshold, they ensure excellent internal consistency reliability. The third step in evaluating the measurement model focused on investigating the convergent validity of each construct measure. This was done by determining the AVE. A higher level of AVE (equal to or higher than 0.50) is suggested [] (Hair et al., 2019). As shown, the AVE of the study constructs ranged from 0.635 to 0.792, indicating an acceptable convergent validity.

Table 1.

Reliability and validity of the study’s variables.

Finally, the discriminant validity of a research study was assessed utilizing three pieces of statistical evidence. Firstly, as proposed by Fornell and Larcker [], it was necessary to confirm that the square root of the construct’s average variance extracted (AVE) was larger than its correlation with any other construct in the structural model in order to ensure the construct’s discriminant validity remained intact. The data in Table 2 showed that each construct’s AVE square root was greater than its correlation with other constructs, demonstrating good discriminant validity.

Table 2.

Discriminant validity based on the Fornell-Larcker criterion.

Secondly, HTMT was also employed to assure construct discriminant validity. Hair et al. [] and Henseler et al. [] demonstrated that a threshold value of 0.90 or less is acceptable. In other words, if the HTMT score is above 0.90, then discriminant validity is affected. As presented in Table 3, the HTMT values between study constructs are all below 0.90, signifying that discriminant validity was successfully attained.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity based on the HTMT.

Thirdly, the cross-loading of indicators method was also examined. Verifying discriminant validity was accomplished by comparing the cross-loadings of each indicator to its assigned construct. If an item is showing a significantly greater correlation with a different construct than its own, then there is potential evidence of a lack of discriminant validity []. Results displayed in Table 4 suggest that all indicators had a higher loading on the assigned construct than other constructs, thereby demonstrating that discriminant validity has been established.

Table 4.

Multicollinearity statistics (VIF) and discriminant validity based on indicator cross-loadings.

4.4. Assessment of the Structural Model

Assessment of the structural model results depends deeply on the characteristics and concepts that underlie multiple regression analysis. Therefore, based on the recommendation of Hair et al. [], firstly, it is crucial to assess the constructs of the structural model in order to ascertain if there is an issue with high multicollinearity. High multicollinearity structural models may change the beta coefficients by decreasing or increasing them, as well as changing their signs. The VIF was used to assess multicollinearity in the data. A VIF value greater than five indicates that multicollinearity is present and should be addressed []. The results shown in Table 4 revealed that multicollinearity in this study did not cause a problem due to the VIF values of all constructs’ indicators below five.

4.5. Assessment of the Predictive Ability of The Structural Model

In order to examine the predictive ability of the structural model, two metrics were employed, namely, the R2 as well as f2. Statistically, R2 measures how much variation in a dependent variable can be explained by its independent variables. According to Hair et al. [] and Henseler et al. [], R2 scores of 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25 can be classified as substantial, moderate, and weak, respectively []. As shown in Table 5, R2 values ranged from 0.401 to 0.724, suggesting a good predictive accuracy of the study model. Additionally, each independent construct in the model was estimated by f2 to determine how well it predicts. As a rule of thumb, effects ranging from 0.02 to 0.15 are deemed small, effects greater than 0.15 to 0.35 are considered medium, and effects greater than 0.35 are considered large []. As shown in Table 5, the f2 values ranged from small (0.033) for PV on purchase intention, to large (2.624) for SMMAs on trendiness, confirming the adequacy of the model.

Table 5.

Structural Model Fit.

4.6. Testing the Study Hypotheses

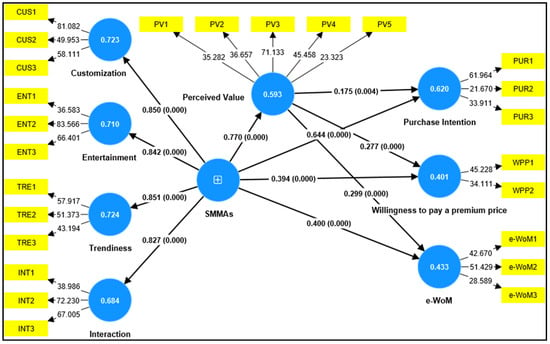

The study hypotheses were evaluated using the PLS-SEM algorithm with bootstrapping technique. To ensure accuracy, bootstrapping with subsamples of 5000 was applied. The results, shown in Table 6 and Figure 2, illustrated that SMMAs significantly impacted restaurant followers’ purchase intention (β = 0.644, t-value = 11.605, p < 0.001), thus supporting hypothesis 1. Moreover, SMMAs also contributed to improving e-WoM and WPP, respectively (β = 0.400, t-value = 6.431, p < 0.001; β = 0.394, t-value = 5.992, p < 0.001), indicating that H2 and H3 were accepted. The results also confirmed that SMMAs highly significantly contributed to improving followers’ PV, which supports H4. In terms of the influence of PV on PUR of restaurant social media followers, the results revealed that PV significantly affected PUR. Hence, H5 was also supported. Similarly, regarding e-WoM and WPP, followers’ perceived value significantly promoted e-WoM (β = 0.299, t-value = 5.283, p < 0.001) and WPP (β = 0.277, t-value = 4.146, p < 0.001), thus confirming hypotheses 6 and 7.

Table 6.

Structural parameter estimates.

Figure 2.

The study’s structural model. Note: Numbers in the blue circles represent R2.

In addition to examining the direct impact of SMMAs on PUR, WPP, and e-WoM, the results of PLS-SEM with bootstrapping technique emphasized that PV significantly positively mediated the relationship between SMMAs and followers’ purchase intention (β = 0.135, t-value = 2.764, p < 0.001), e-WoM (β = 0.135, t-value = 2.764, p < 0.001), and WPP (β = 0.135, t-value = 2.764, p < 0.001), confirming the hypotheses 8, 9, and 10, respectively.

To examine the contribution of PV in the nexus between SMMAs and PUR, WPP, and e-WoM, suggestions proposed by Kelloway [] and Zhao et al. [] were utilized. They illustrated that partial mediation was achieved when direct and indirect paths were significant. Meanwhile, full mediation was done when the direct path was insignificant and the indirect path significant. The results in Table 6 demonstrated that PV has a significant partial mediation effect on these relationships, where both direct and direct paths were significant.

5. Discussion

This study aims to empirically explore the direct effect of SMMAs on PV, PUR, WPP, and e-WoM among restaurant social media followers. Further, it aims to prove the direct effect of PV on followers’ PUR, WPP, and e-WoM. Finally, it aims to to examine the potential mediating effects of PV on the SMMAs-PUR, SMMAs-WPP, and SMMAs-e-WoM relationships. The results of this study’s hypotheses tests have revealed a number of significant findings. First, the findings revealed that SMMAs substantially contributed to enhancing restaurant social media followers’ purchase intention, promoted positive e-WoM, and increased restaurant social media followers’ WPP for restaurant products and services. This is in line with the results of prior studies, which foster the notion that SMMAs significantly impacted consumers’ PUR i.e., [,,]. Further, these findings agreed with those concluded by Ajina [] and López and Sicilia [], who found that when businesses make effective use of SMMAs that align with consumer needs and preferences, e-WoM can be positively influenced. However, when social media marketing efforts are poorly executed, consumer e-WoM can suffer. Additionally, the results of this study further confirm the previous findings that SMMAs have a positive effect on consumers’ WPP [,,].

Second, the findings of this study demonstrated that restaurant followers’ perceived value was highly significantly impacted by SMMAs. This finding fosters the notion that there is a strong relationship between SMMAs and customer perceived value [,,]. In other words, quality content, responsiveness to customer needs, contacting each user personally, and positive engagement with the brand all make a significant contribution in increasing customer perceived value of a restaurant’s products and services.

Third, the results showed that PV is a major factor in influencing the responses of restaurant social media followers in terms of PUR, WPP, and e-WoM. These findings support the results of the prior studies that assured the significant associations between PV and e-WoM [,,], PV and WPP i.e., [,], and PV and PUR [,]. Accordingly, it can be suggested that the greater the value perceived, the more likely it is to generate positive e-WoM, increase WPP, and boost PUR among restaurant social media followers. In other words, when customers perceive a restaurant to be of high value, they are more likely to purchase its products, pay more money for its products, and share their positive experiences with others. On the other hand, if customers perceive a restaurant to be of low value, they may be less likely to share their experiences or even avoid the restaurant altogether.

Fourth, in the context of the intervening role of PV on the SMMAs-e-WoM, SMMAs-WPP, and SMMAs-PUR relationships, the study found that PV has a significant partial impact on these relationships. More specifically, the findings of this study emphasized that, by increasing their degree of interactivity, entertainment, customization, and trendiness, restaurants could boost customer perceived value. This would in turn increase customer purchase intention, spread positive e-word of mouth, and increase customers’ willingness to pay more for the restaurant’s products and services. These findings are to some extent consistent with those found by Moslehpour et al. [], who demonstrated that the PV partially mediated the relationship between SMMAs and purchase intention.

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The present study has made a substantial contribution to the existing literature review on SMMAs, PUR, WPP, e-WoM, and PV in the casual dining restaurant industry context as follows. First, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first that examines the impact of SMMAs on PUR, WPP, e-WoM, and PV in the casual dining restaurant industry context, particularly in a developing country such as Saudi Arabia. The findings of the study emphasized the substantial effect of SMMAs on customers’ behavioral intentions in terms of PUR, WPP, e-WoM, and PV. Second, this study examined the intervening role of PV in the relationships amongst SMMAs, PUR, WPP, and e-WoM based on the S-O-R model. Using this model, the findings of the study illustrated that the higher the perceived customization, entertainment, trendiness, and interaction of SMM (Stimuli), the more likely it is to increase followers’ perceived value (Organism), which in turn leads to an increase in PUR, WPP, and positive e-WoM (Response). These findings support and extend the S-O-R model in the restaurant industry context. This study has developed and validated a new model that takes into account social media marketing activities (SMMAs), perceived value (PV), purchase intention (PUR), and electronic word-of-mouth (e-WoM). This contributes to the existing literature on social media marketing in the restaurant industry context. The findings of this study are significant as they can be used as a guide for future research. Additionally, they provide an in-depth understanding of the key factors that have a direct and indirect effect on the behavioral intention of restaurant followers on social media platforms, which could be beneficial for scholars in hospitality research.

6.2. Practical Implications

The findings of the study have several implications for restaurant operators and marketers. First, the study’s findings revealed that SMMAs, directly and indirectly, contributed to enhancing PUR, WPP, and generating positive e-WoM. Considering social media’s significant role in shaping consumers’ behavior, companies need to shift their marketing communication strategies by investing more in social media rather than traditional marketing. Hence, restaurant operators should consider implementing social media marketing activities to increase their followers’ purchase intention, willingness to pay a premium price, and positive word of mouth. To do this, operators should focus on creating engaging content that resonates with their target audience. Customization is a great way to engage customers and increase their behavioral intention. Restaurants can use social media to offer customers personalized experiences, such as customizing menu items or offering discounts for loyal customers. This will make customers feel valued and more likely to return. Additionally, restaurants can use social media to entertain their followers by creating content that is fun and engaging. This could include hosting contests, sharing recipes, or providing behind-the-scenes looks at the restaurant. Trendiness is also important for restaurants on social media as it helps them stay relevant and attract new customers. Restaurants can do this by staying up-to-date on the latest trends in food and beverage, as well as participating in conversations about current events or popular topics. Finally, interaction is key for restaurants on social media. By responding to customer comments and questions quickly and engaging with followers regularly, restaurants can create a sense of community that will encourage positive word of mouth and increase willingness to pay a premium price.

Second, PV has a significant positive impact on followers’ behavioral intentions, particularly positive e-WoM. Therefore, it is important for restaurants to create a positive perception of value by providing quality food and service at reasonable prices. Additionally, restaurants should use social media platforms to showcase their unique offerings and highlight customer reviews in order to create an atmosphere of trust and credibility that will encourage customers to share their experiences with others.

Third, restaurant marketers and operators should take advantage of the findings of this study to maximize their marketing efforts. By understanding the mediating role of PV in the relationship between SMMAs and PUR, WPP, and e-WoM, restaurant marketers and operators can create strategies that will increase customer engagement and loyalty. For example, they can focus on providing customers with customized experiences through social media platforms such as personalized offers or discounts. Further, this can also be done by emphasizing the quality of the food, the atmosphere, and the overall customer experience. Additionally, restaurant marketers and operators should strive to create a positive e-WoM environment by encouraging customers to share their experiences online. This can be done through social media campaigns or other forms of online advertising. By implementing these strategies, restaurant marketers and operators can increase customer perceived value, engagement, and loyalty, which will ultimately lead to increased PUR, WPP, and e-WoM.

7. Research Limitations and Future Directions

This study had several limitations. It was limited to the followers of ten casual dining restaurants in Saudi Arabia (Five from Riyad, the capital of Saudi Arabia; three from Jeddah; and two from Damam), using SMMAs, PV, PUR, WPP, and e-WoM. The results of this study may not be applicable to other countries, organizations, cultures, or work settings. Therefore, it is necessary to reassess and verify the findings of this study in different restaurant industry contexts to gain a better understanding of the topic. Second, the study conducted only looked at the potential of PV to act as a mediator in the relationship between SMMAs and PUR, WPP, and e-WoM. It is suggested that further research should be done to explore other possible mechanisms (mediators), such as customer trust and customer satisfaction. The demographics of the participants surveyed in this study such as age, and educational background, as well as usage period for social media, might moderate the relationship between SMMAs and users’ behavioral intentions in ways not explored in this study. Future research might investigate the potential moderating impact of these factors in these relationships. Lastly, in our research we used SMMAs as a single-dimensional construct and did not examine its associated four dimensions separately. Further research should be conducted to include all four dimensions in order to determine which one is the most predictive in this relationship. This could provide valuable insight into the role of each one in these relationships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H.A.; methodology, A.H.A., A.E.E.S., M.A.E., M.A. and A.A.E.; software, A.H.A., M.A.B. and T.H.H.; validation, A.H.A., A.E.E.S., M.A.E. and A.A.E.; formal analysis, A.H.A., M.A.B., W.G.A. and T.H.H.; data curation, A.H.A., A.S.M.A., A.E.E.S., M.A.E. and A.A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H.A., M.A.B., W.G.A., M.A. and T.H.H.; writing—review and editing, A.E.E.S., M.A.E., A.S.M.A. and A.A.E.; funding acquisition, A.H.A., M.A. and M.A.B.; supervision, A.H.A., A.S.M.A. and T.H.H.; visualization, W.G.A., M.A.E. and A.A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Grant No. 1985], through its KFU Research Summer initiative.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the deanship of the scientific research ethical committee, King Faisal University (Project number: Grant 1985, date of approval: 1 July 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data from this study can be obtained from the correspondence authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

Conflict of interest is not declared by the authors.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Study’s constructs and their related items.

Table A1.

Study’s constructs and their related items.

| Construct | Items | Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Customization (CUS) | CUS1 | It is possible to search for customized information on restaurant X’s social media |

| CUS2 | Restaurant X’s social media provide lively feed information I am interested in | |

| CUS3 | Restaurant X offers customized services through its social media | |

| Entertainment (ENT) | ENT1 | The content found in restaurant X’s social media seems interesting. |

| ENT2 | Utilizing the social media channels of restaurant X is exciting. | |

| ENT3 | It is fun to collect information on products through restaurant X’s social media. | |

| Trendiness (TRE) | TRE1 | Restaurant X’s social media content is up-to-date |

| TRE2 | Using restaurant X’s social media is very trendy. | |

| TRE3 | The content on restaurant X’s social media is the newest information. | |

| Interaction (INT) | INT1 | I can easily share my opinions through restaurant X’s social media. |

| INT2 | It is easy to convey my opinions or conversation with other users through restaurant X’s social media | |

| INT3 | It is possible to have two-way interaction through restaurant X’s social media. | |

| Perceived Value (PV) | PV1 | The social media page of restaurant x makes me feel more socially accepted. |

| PV2 | The social media page of restaurant x is useful and valuable for me. | |

| PV3 | The social media page of restaurant x is an important source of information for me. | |

| PV4 | Restaurant x’s products and services have a consistent level of quality. | |

| PV5 | Restaurant x’s products and services represent excellent value for money. | |

| Purchase Intention (PUR) | PUR1 | I plan to purchase restaurant products that I have seen on social media. |

| PUR2 | I intend to purchase restaurant products that I like based on social media interaction. | |

| PUR3 | I am very likely to purchase restaurant products recommended by my friends on social media. | |

| Willingness to Pay a Premium Price (WPP) | WPP1 | I would pay more price for restaurant x than for similar restaurants. |

| WPP2 | I intend to purchase from restaurant x even if another brand advertises a lower price. | |

| e-WoM | e-WoM1 | I will post positive comments about restaurant X on my social media. |

| e-WoM2 | I will recommend using restaurant x through my social media. | |

| e-WoM3 | I will recommend using restaurant x to my social media acquaintances. |

References

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.D.; Rosenberger, P.J.; Leung, W.K.S.; Ting, H. Investigating the role of social media marketing on value co-creation and engagement: An empirical study in China and Hong Kong. Australas. Mark. J. 2021, 29, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuseir, M.T. Is advertising on social media effective? An empirical study on the growth of advertisements on the Big Four (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp). Int. J. Procure. Manag. 2020, 13, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.J.; Park, J.; Choi, Y.J. The Effect of Social Media Usage Characteristics on e-WoM, Trust, and Brand Equity: Focusing on Users of Airline Social Media. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisniyanti, A.; Fah, C.T. The Impact of Social Media Marketing on Purchase Intention of Skincare Products Among Indonesian Young Adults. Eurasian J. Soc. Sci. 2022, 10, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önder, L.; Çakıroğlu, A. The relationships among social media marketing, online consumer engagement, purchase intention and brand loyalty. Bus. Manag. Stud. Int. J. 2021, 9, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrkar, A.; Hajimohammadi, M.; Aramoon, E.; Aramoon, V. Effect of the Social Media Marketing Strategy on Customer Participation Intention in Light of the Mediating Role of Customer Perceived Value. Tržište 2021, 33, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, A.H.; Mohamed, S.A.K.; Khalil, A.A.F.; Albakhit, A.I.; Alarjani, A.J.N. Modeling the relationship between perceived service quality, tourist satisfaction, and tourists’ behavioral intentions amid COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence of yoga tourists’ perspectives. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1003650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, K.K.; Hult, G.T.M. Customer behavioral intentions for online purchases: An examination of fulfillment method and customer experience level. J. Oper. Manag. 2006, 24, 124–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshardoost, M.; Eshaghi, M.S. Destination image and tourist behavioural intentions: A meta-analysis. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.; Chang, C.; Cheng, H.; Fang, Y. Determinants of customer repurchase intention in online shopping. Online Inf. Rev. 2009, 33, 761–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelia, R.; Hidayatullah, S. The effect of Instagram engagement to purchase intention and consumers’ luxury value perception as the mediator in the skylounge restaurant. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2020, 5, 958–966. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Li, M. Exploring new factors affecting purchase intention of mobile commerce: Trust and social benefit as mediators. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2019, 17, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Sicilia, M. Determinants of e-WoM Influence: The Role of Consumers’ Internet Experience. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2014, 9, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.K.; Seo, Y.; Yoon, S. e-WoM messaging on social media. Internet Res. 2017, 27, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, P.; Augusto, M.; Wallace, E. Improving consumers’ willingness to pay using social media activities. J. Serv. Mark. 2018, 32, 880–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, F.X.; Vlosky, R.P. Consumer willingness to pay price premiums for environmentally certified wood products in the U.S. For. Policy Econ. 2007, 9, 1100–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgarpour, R.; Hamid, A.B.A.; Sulaiman, Z. A Review on Customer Perceived Value and Its Main Components. GATR Glob. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2014, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Wang, W. The influence of perceived value on purchase intention in social commerce context. Internet Res. 2017, 27, 772–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, Q.; Tran, X.; Misra, S.; Maskeliūnas, R.; Damaševičius, R. Relationship between Convenience, Perceived Value, and Repurchase Intention in Online Shopping in Vietnam. Sustainability 2018, 10, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, E.A.d.M.; Alfinito, S.; Curvelo, I.C.G.; Hamza, K.M. Perceived value, trust and purchase intention of organic food: A study with Brazilian consumers. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1070–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaysha, J.R. An examination of the factors affecting consumer’s purchase decision in the Malaysian retail market. Int. J. Crowd Sci. 2018, 2, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Charni, H.; Khan, S. Impact of Social Media Marketing on Consumer Behavior in Saudi Arabia. PalArch’s J. Archaeol. Egypt/Egyptol. 2021, 18, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Moslehpour, M.; Dadvari, A.; Nugroho, W.; Do, B. The dynamic stimulus of social media marketing on purchase intention of Indonesian airline products and services. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2021, 33, 561–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.C.; Gupta, D.D. An investigative study of factors influencing dining out in casual restaurants among young consumers. Eur. Bus. Manag. 2018, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Malik, G.; Gupta, S. Impact of Extended Marketing Mix of Casual Dining Restaurants on Customer Experience and Customer Satisfaction. ECS Trans. 2022, 107, 19155–19161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.M. Effectiveness of social media marketing on enhancing performance: Evidence from a casual-dining restaurant setting. Tour. Econ. Bus. Financ. Tour. Recreat. 2021, 27, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, R.B.; Crews, T.B.; Gustafson, C.; Strick, S. Use of Social Networking Sites in the Restaurant Industry: Best Practices. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2012, 15, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajli, N. Social commerce constructs and consumer’s intention to buy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, P.; Frost, W.; Williams, K.; Laing, J. The Acceptance or Rejection of Social Media: A Case Study of Rochford Winery Estate in Victoria, Australia. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2013, 13, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, T. The New Community Rules, 1st ed.; O’Reilly Media, Incorporated: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, M.; Barker, D.I.; Bormann, N.F.; Neher, K.E. Social Media Marketing: A Strategic Approach; CENGAGE learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tuten, T.L.; Solomon, M.R. Social Media Marketing; Sage: New Delhi, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, A.J.; Ko, E. Do social media marketing activities enhance customer equity? An empirical study of luxury fashion brand. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1480–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, K. An empirical study the effect of social media marketing activities upon customer satisfaction, positive word-of-mouth and commitment in indemnity insurance service. In Proceedings of the International Marketing Trends Conference, Paris, France, 23 January 2015; pp. 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, M.; Rahman, Z. The influence of social media marketing activities on customer loyalty: A study of e-commerce industry. Benchmarking Int. J. 2018, 25, 3882–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godey, B.; Manthiou, A.; Pederzoli, D.; Rokka, J.; Aiello, G.; Donvito, R.; Singh, R. Social media marketing efforts of luxury brands: Influence on brand equity and consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5833–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Keh, H.T. A re-examination of service standardization versus customization from the consumer’s perspective. J. Serv. Mark. 2016, 30, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, V.; Peltier, J.W.; Schultz, D.E. Social media and consumer engagement: A review and research agenda. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2016, 10, 268–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, T.; Eastin, M.S.; Bright, L. Exploring Consumer Motivations for Creating User-Generated Content. J. Interact. Advert. 2008, 8, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naaman, M.; Becker, H.; Gravano, L. Hip and trendy: Characterizing emerging trends on Twitter. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 62, 902–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangold, W.G.; Faulds, D.J. Social media: The new hybrid element of the promotion mix. Bus. Horiz. 2009, 52, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntinga, D.G.; Moorman, M.; Smit, E.G. Introducing COBRAs: Exploring motivations for brand-related social media use. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 13–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajina, A.S. The perceived value of social media marketing: An empirical study of online word-of-mouth in Saudi Arabian context. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2019, 6, 1512–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fernández, R.; Iniesta-Bonillo, M.Á. The concept of perceived value: A systematic review of the research. Mark. Theory 2007, 7, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Adly, M.I. Modelling the relationship between hotel perceived value, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Po Lo, H.; Chi, R.; Yang, Y. An integrated framework for customer value and customer-relationship-management performance: A customer-based perspective from China. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2004, 14, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathwick, C.; Malhotra, N.; Rigdon, E. Experiential value: Conceptualization, measurement and application in the catalog and Internet shopping environment. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Seok, J.; Kim, Y. Unveiling ways to reach organic purchase: Green perceived value, perceived knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Wu, K. Sustainability development in hospitality: The effect of perceived value on customers’ green restaurant behavioral intention. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinillo, S.; Aguilar-Illescas, R.; Anaya-Sánchez, R.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. Social commerce website design, perceived value and loyalty behavior intentions: The moderating roles of gender, age and frequency of use. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, J.; Trujillo, A. Service quality dimensions and superior customer perceived value in retail banks: An empirical study on Mexican consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lin, C. Understanding the effect of social media marketing activities: The mediation of social identification, perceived value, and satisfaction. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 140, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobeiri, S.; Laroche, M.; Mazaheri, E. Shaping e-retailer’s website personality: The importance of experiential marketing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, C.K.; Gantasala, S.B.; Prabhakar, G.V. SERVQUAL, customer satisfaction and behavioural intentions in retailing. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2010, 17, 200–213. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S.; Yu, J. Determinants of Behavioral Intentions in the Context of Sport Tourism with the Aim of Sustaining Sporting Destinations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhaily, L.; Soelasih, Y. What Effects Repurchase Intention of Online Shopping. Int. Bus. Res. 2017, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the Internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataineh, A.Q. The Effect of eCRM Practices on e-WoM on Banks’ SNSs: The Mediating Role of Customer Satisfaction. Int. Bus. Res. 2015, 8, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, C.; Zhou, G. Willingness to pay a price premium for energy-saving appliances: Role of perceived value and energy efficiency labeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enehasse, A.; Sağlam, M. The impact of digital media advertising on consumer behavior intention: The moderating role of brand trust. J. Mark. Consum. Res. 2020, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzigeorgiou, C. Modelling the impact of social media influencers on behavioural intentions of millennials: The case of tourism in rural areas in Greece. J. Tour. 2017, 3, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dülek, B.; Aydin, İ. Effect of Social Media Marketing on e-WoM, Brand Loyalty, and Purchase Intent; Bingöl Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi: Bingöl, Türkiye, 2020; pp. 271–288. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, B.; Aljarah, A.; Sawaftah, D. Linking Social Media Marketing Activities to Revisit Intention through Brand Trust and Brand Loyalty on the Coffee Shop Facebook Pages: Exploring Sequential Mediation Mechanism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Hafeez, H.; Manzoor, D.S.; Salman, D.F. Impact of Social Networking Sites on Consumer Purchase Intention: An Analysis of Restaurants in Karachi. J. Bus. Strateg. 2017, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzin, M.; Sadeghi, M.; Fattahi, M.; Eghbal, M.R. Effect of Social Media Marketing and e-WoM on Willingness to Pay in the Etailing: Mediating Role of Brand Equity and Brand Identity. Bus. Perspect. Res. 2022, 10, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Martinez, B.; McClure, C.S.; Kim, S.H. e-WoM intentions towards social media messages. Atl. Mark. J. 2016, 5, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Adaptive, How Social Media Amplifies the Power of Word-of-Mouth. Available online: https://www.reutersevents.com/marketing/brand-marketing/how-social-media-amplifies-power-word-mouth (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Andervazh, L.A.; Albonaiemi, E.M.; Zarbazoo, M.A. Effect of Using Social Media on Word of Mouth Advertising for Tourism Industry. Utop. Prax. Latinoam. 2020, 25, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinerean, S.; Cetina, I.; Dumitrescu, L.; Tichindelean, M. The Effects of Social Media Marketing on Online Consumer Behavior. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Khan, Z.; Zhang, Y. The Influence of Social Media Marketing on Apparel Brands’ Customers’ Satisfaction: The Mediation of Perceived Value. Asian Acad. Manag. J. 2020, 25, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafidon, M.A.A.Z.; Margono, M.; Sunaryo, S. Social Media Marketing on Purchase Intention Through Mediated Variables of Perceived Value And Perceived Risk. Interdiscip. Soc. Stud. 2022, 1, 1182–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgünescedil, B. Relative Importance of Perceived Value, Satisfaction and Perceived Risk on Willingness to Pay More. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2015, 5, 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Sukaris, S.; Hartini, S.; Mardhiyah, D. The effect of perceived value by the tourists toward electronic word of mouth activity: The moderating role of conspicuous tendency. J. Siasat Bisnis 2020, 24, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadara, P.D.; Fanggidae, J.P. The Role of Perceived Value and Gratitude on Positive Electronic Word of Mouth Intention in the Context of Free Online Content. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Chang. 2020, 11, 391–405. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Chen, K.; Chen, P.; Cheng, S. Perceived value, transaction cost, and repurchase-intention in online shopping: A relational exchange perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2768–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, J.; Aditi, B.; Nagoya, R.; Wisnalmawati, W.; Nurcholifah, I. Tourist visiting interests: The role of social media marketing and perceived value. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2022, 6, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, H. Social media and human need satisfaction: Implications for social media marketing. Bus. Horiz. 2015, 58, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Chen, X.; Zheng, H. Exploring an adverse impact of smartphone overuse on academic performance via health issues: A stimulus-organism-response perspective. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2021, 40, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Eckman, M.; Yan, R. Application of the Stimulus-Organism-Response model to the retail environment: The role of hedonic motivation in impulse buying behavior. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2011, 21, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.B. Researching Internet-Based Populations: Advantages and Disadvantages of Online Survey Research, Online Questionnaire Authoring Software Packages, and Web Survey Services. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2005, 10, JCMC1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, Z.; Abosag, I.; Zabkar, V. All in the Value: The Impact of Brand and Social Network Relationships on the Perceived Value of Customer Endorsed Facebook Advertising. Eur. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 1704–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emini, A.; Zeqiri, J. Social Media Marketing and Purchase Intention: Evidence from Kosovo. Ekon. Misao Praksa 2021, 30, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomsma, A. Systems under indirect observation: Causality, structure, prediction. In The Robustness of Lisrel Against Small Sample Sizes in Factor Analysis Models; North-Holland Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982; pp. 149–173. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N. Detecting Multicollinearity in Regression Analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2020, 8, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway, E.K. Structural equation modelling in perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 16, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, B.K.P.D.; Dahnil, M.I.; Yi, W.J. The Impact of Social Media Marketing Medium toward Purchase Intention and Brand Loyalty among Generation Y. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 148, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |