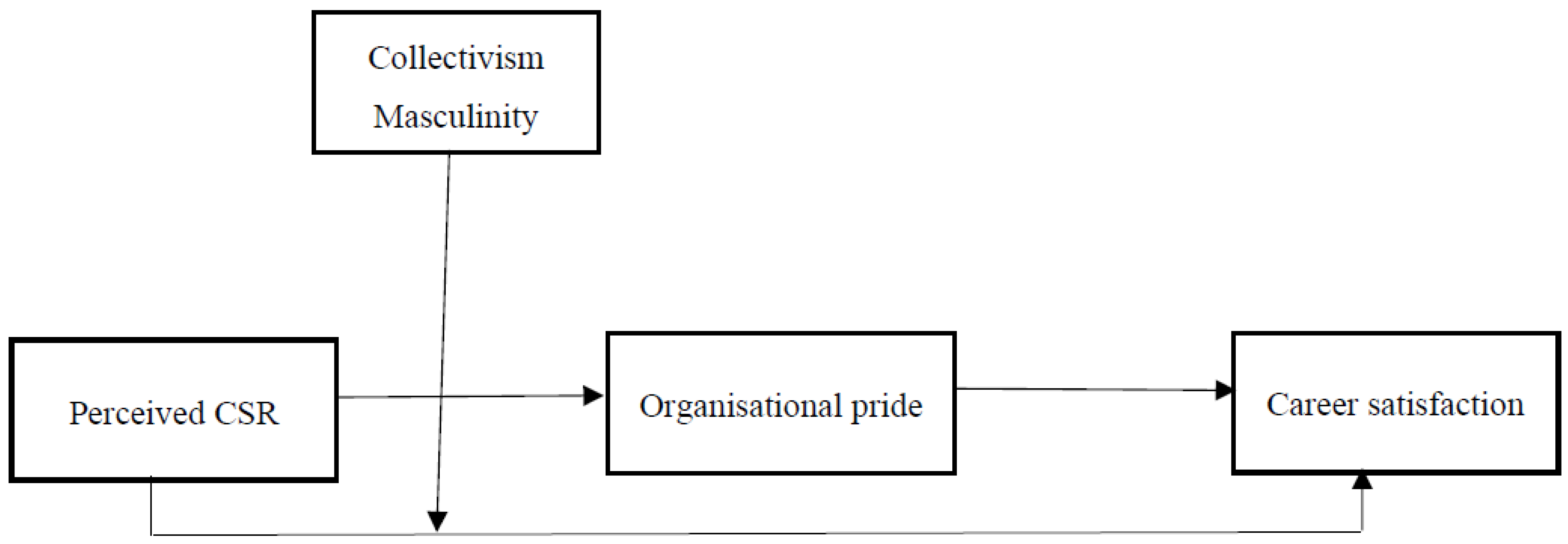

Perceived CSR on Career Satisfaction: A Moderated Mediation Model of Cultural Orientation (Collectivism and Masculinity) and Organisational Pride

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Perceived CSR

2.2. Organisational Pride

2.3. Career Satisfaction

2.4. Collectivism and Masculinity

2.5. Perceived CSR and Career Satisfaction

2.6. Organisational Pride as a Mediator

2.7. Collectivism and Masculinity as Moderators

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Instrument Establishment

3.3. Information Analysis

3.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

4. Results

4.1. Direct and Mediation Effects

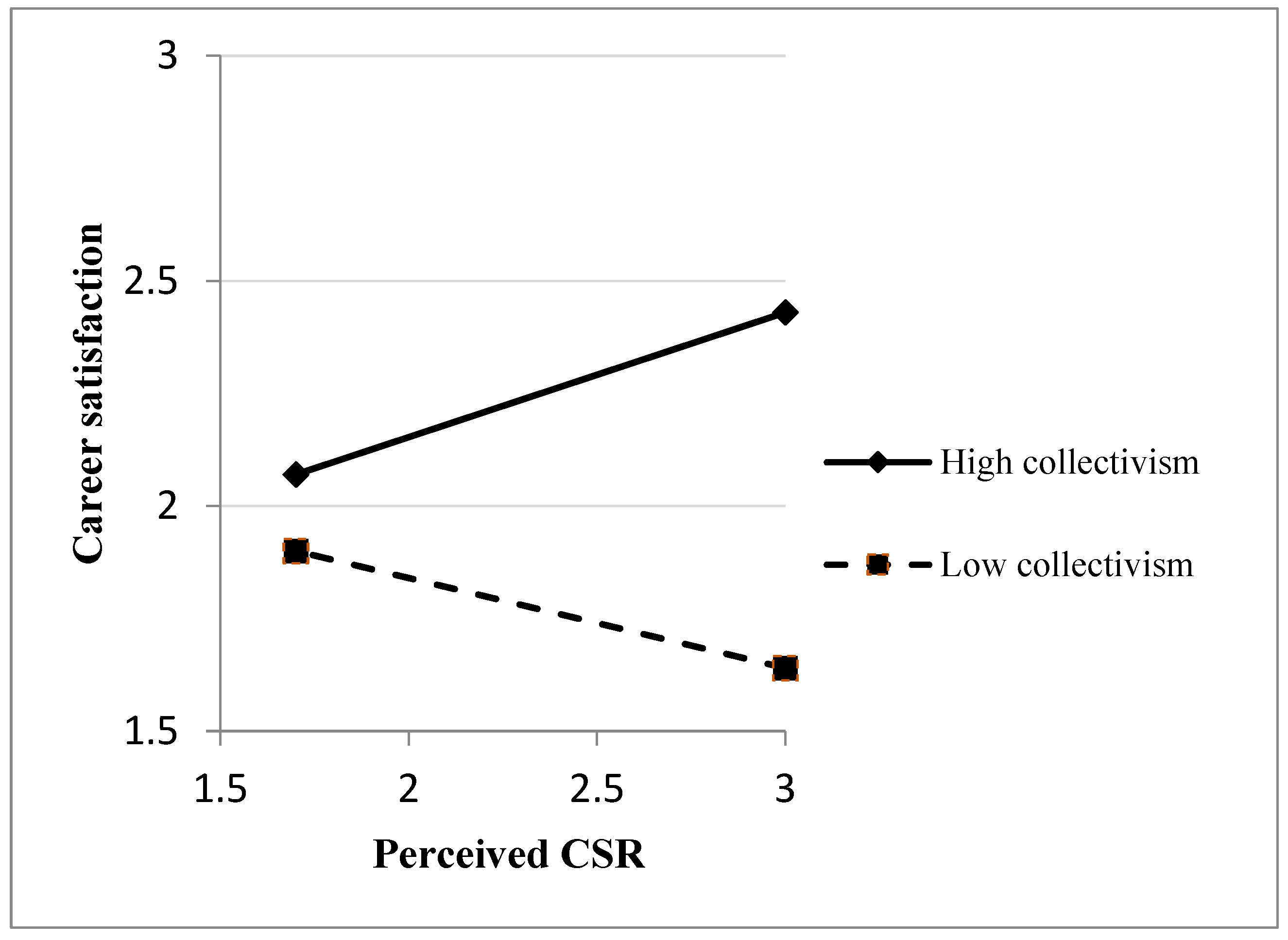

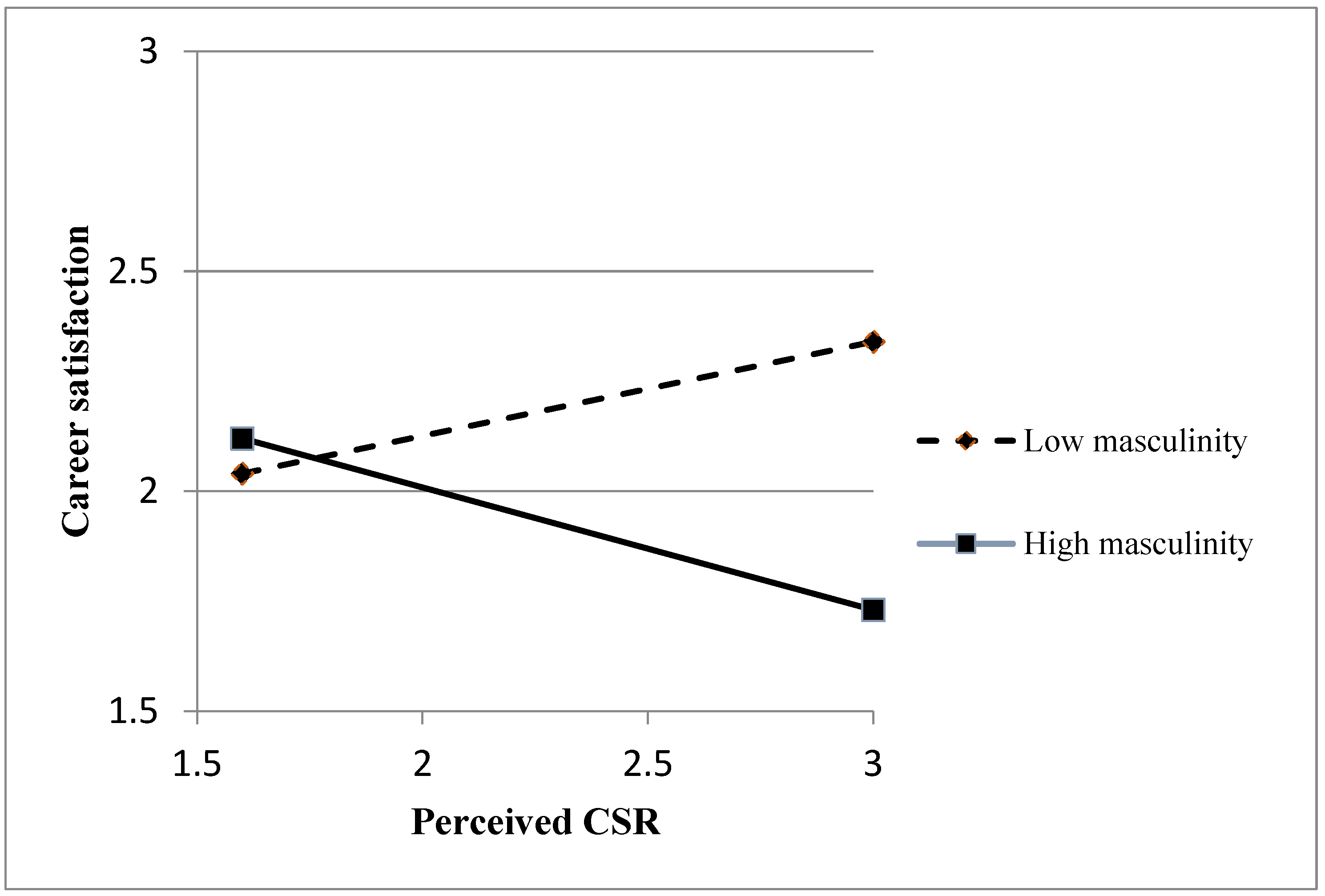

4.2. Moderating Effects

4.3. Conditional Indirect Effects

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shen, J.; Zhang, H. Socially responsible human resource management and employee support for external CSR: Roles of organizational CSR climate and perceived CSR directed toward employees. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, P.S.; Newman, A. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment and the moderating role of collectivism and masculinity: Evidence from China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donia, M.B.; Ronen, S.; Sirsly, C.A.T.; Bonaccio, S. CSR by any other name? The differential impact of substantive and symbolic CSR attributions on employee outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Corporate social responsibility, multi-faceted job-products, and employee outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.M.; Moon, T.W.; Ko, S.H. How employees’ perceptions of CSR increase employee creativity: Mediating mechanisms of compassion at work and intrinsic motivation. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 153, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fu, Y.; Qiu, H.; Moore, J.H.; Wang, Z. Corporate social responsibility and employee outcomes: A moderated mediation model of organizational identification and moral identity. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Sohail, M.S. The Impact of Employees’ Perceptions of CSR on Career Satisfaction: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Sohail, M.S.; Jumaan, I.A.M. CSR Perceptions and Career Satisfaction: The Role of Psychological Capital and Moral Identity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A. Corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: Enabling employees to employ more of their whole selves at work. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surroca, J.; Tribó, J.A.; Waddock, S. Corporate responsibility and financial performance: The role of intangible resources. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 463–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, E.Y.; Jung, H.; Park, I.J. Psychological factors linking perceived CSR to OCB: The role of organizational pride, collectivism, and person–organization fit. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelade, G.A.; Dobson, P.; Auer, K. Individualism, masculinity, and the sources of organizational commitment. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2008, 39, 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Lee, C.K.; Kim, H. The influence of corporate social responsibility on travel company employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Sial, M.S.; Ahmad, N.; Sehleanu, M.; Li, Z.; Zia-Ud-Din, M.; Badulescu, D. CSR as a potential motivator to shape employees’ view towards nature for a sustainable workplace environment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S. A matter of reputation and pride: Associations between perceived external reputation, pride in membership, job satisfaction and turnover intentions. Br. J. Manag. 2013, 24, 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A. Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism programme. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 857–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D.M.; Turban, D.B. The value of organizational reputation in the recruitment context: A brand-equity perspective. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 33, 2244–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Parasuraman, S.; Wormley, W.M. Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis, H.C.; McCusker, C.; Hui, C.H. Multimethod probes of individualism and collectivism. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, O.; Payaud, M.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Rupp, D.E.; Farooq, M. The multiple pathways through which internal and external corporate social responsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: The moderating role of cultural and social orientations. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 954–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhapakdi, A.; Lee, D.J.; Sirgy, M.J.; Roh, H.; Senasu, K.; Yu, G.B. Effects of perceived organizational CSR value and employee moral identity on job satisfaction: A study of business organizations in Thailand. Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 8, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldo, S.; Ciacci, A.; Penco, L. Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility and Job Satisfac-tion in the Retail Industry: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. In Managing Sustainability: International Series in Advanced Management Studies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onkila, T.; Sarna, B. A systematic literature review on employee relations with CSR: State of art and future research agenda. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Cheema, S.; Javed, F. Activating employee’s pro-environmental behaviors: The role of CSR, organizational identification, and environmentally specific servant leadership. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Umrani, W.A. Corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behavior at workplace: The role of moral reflectiveness, coworker advocacy, and environmental commitment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, L. Does perceived corporate social responsibility motivate hotel employees to voice? The role of felt obligation and positive emotions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob, U.; Podnar, K. Corporate marketing and the role of internal CSR in employees’ life satisfaction: Exploring the relationship between work and non-work domains. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Shao, R.; Skarlicki, D.P.; Paddock, E.L.; Kim, T.Y.; Nadisic, T. Corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: The moderating role of CSR-specific relative autonomy and individualism. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 559–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, B.; Ong, T.S.; Meero, A.; Abdul Rahman, A.A.; Ali, M. Employee-perceived corporate social responsibility (CSR) and employee pro-environmental behavior (PEB): The moderating role of CSR skepticism and CSR authenticity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilkhanizadeh, S.; Karatepe, O.M. An examination of the consequences of corporate social responsibility in the airline industry: Work engagement, career satisfaction, and voice behavior. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2017, 59, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A.; Van Der Heijden, B.I.; Akkermans, J. Sustainable careers: Towards a conceptual model. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 117, 103196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Skarlicki, D.; Shao, R. The psychology of corporate social responsibility and humanitarian work: A person-centric perspective. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 6, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.; Yam, K.C.; Aguinis, H. Employee perceptions of corporate social responsibility: Effects on pride, embeddedness, and turnover. Pers. Psychol. 2019, 72, 107–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsachouridi, I.; Nikandrou, I. Organizational virtuousness and spontaneity: A social identity view. Pers. Rev. 2016, 45, 1302–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costas, J.; Kärreman, D. Conscience as control–managing employees through CSR. Organization 2013, 20, 394–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzach, Y.; Pazy, A. Cognitive versus non-cognitive individual differences and the dynamics of career success. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 64, 701–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C.; Gelfand, M.J. Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stipek, D. Differences between Americans and Chinese in the circumstances evoking pride, shame, and guilt. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1998, 29, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, D.A.; Siegel, D.; Javidan, M. Components of transformational leadership and corporate social responsibility. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1703–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blodgett, J.G.; Lu, L.C.; Rose, G.M.; Vitell, S.J. Ethical sensitivity to stakeholder interests: A cross-cultural comparison. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2001, 29, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, M.W.; Den Hartog, D.N.; Mitchelson, J.K. Research on leadership in a cross-cultural context: Making progress, and raising new questions. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 729–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Tjosvold, D. Collectivist values for learning in organizational relationships in China: The role of trust and vertical coordination. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2006, 23, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, S.Y. The influence of cultural values on perceptions of corporate social responsibility: Application of Hofstede’s dimensions to Korean public relations practitioners. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Ding, C.G. The influence of culture on industrial buying selection criteria in Taiwan and Mainland China. Ind. Mark. Manag. 1995, 24, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.; Roy, A.; Mukhopadhyay, K. The impact of cultural values on marketing ethical norms: A study in India and the United States. J. Int. Mark. 2006, 14, 28–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Yoo, B. Cultural influences on service quality expectations. J. Serv. Res. 1998, 1, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mertler, C.A.; Vannatta, R.A. Advanced and Multivariate Statistical Methods: Practical Application and Interpretation, 3rd ed.; Pyrczak Publishing: Glendale, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Takeuchi, N. A lifespan perspective for understanding career self-management and satisfaction: The role of developmental human resource practices and organizational support. Hum. Relat. 2018, 71, 73–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.K.F.; Kim, S.; Hwang, Y. Effects of Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Performance on Hotel Employees’ Behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2022, 23, 1145–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, E.L. Linking Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Well-Being—A Eudaimonia Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N = 383 | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 259 (67.6%) |

| Female | 124 (32.4%) | |

| Age | 20–30 years | 49 (12.8%) |

| 31–40 years | 192 (50.1%) | |

| 41–50 years | 105 (27.4%) | |

| Above 50 years | 37 (9.7%) | |

| Education | Secondary | 16 (4.2%) |

| Certification/Diploma | 59 (15.4%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 172 (44.9%) | |

| Master’s degree | 124 (32.4%) | |

| Doctorate degree | 12 (3.1%) | |

| Type of organisation | Public | 197 (51.4%) |

| Private | 186 (48.6%) | |

| Types of industry | Oil and gas | 45 (11.7%) |

| Agriculture | 47 (12.3%) | |

| Mining | 59 (15.4%) | |

| Hospitality | 39 (10.2%) | |

| Construction | 64 (16.7%) | |

| Transportation | 69 (18%) | |

| Healthcare | 60 (15.7%) | |

| Nationality | Saudi | 99 (25.8%) |

| Non-Saudi | 284 (74.2%) | |

| Total experience | 5–10 years | 87 (22.7%) |

| 10–15 years | 146 (38.1%) | |

| 15–20 years | 104 (27.2%) | |

| Above 20 years | 46 (12%) | |

| Experience in current organisation | Less than a year | 11 (2.9%) |

| 1–5 years | 32 (8.4%) | |

| 5–10 years | 91 (23.7%) | |

| 10–15 years | 162 (42.3%) | |

| Above 15 years | 87 (22.7%) | |

| Job position | Top management | 79 (20.6%) |

| Middle management | 126 (32.9%) | |

| First line management | 112 (29.2%) | |

| Non-management | 40 (10.5%) | |

| Technical | 15 (3.9%) | |

| Other | 11 (2.9%) |

| Model | χ2/df | CFI | NFI | GFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five-factor model (Hypothesised model) | 1.86 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.06 |

| Four-factor model (combining collectivism and masculinity) | 2.48 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.08 |

| Three-factor model (combining perceived CSR and organisational pride) | 3.59 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.21 |

| Two-factor model (combining perceived CSR, organisational pride, collectivism, and masculinity) | 4.48 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.62 | 0.59 | 0.27 |

| One-factor model (combining all variables) | 7.11 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.38 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. Gender | −0.04 | 1 | |||||||

| 3. Industry type | 0.01 | 0.03 | 1 | ||||||

| 4. Tenure | 0.62 * | −0.06 | 0.05 | 1 | |||||

| 5. Organisational pride | 0.17 * | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.13 * | (0.786) | ||||

| 6. Perceived CSR | −0.08 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.19 * | 0.463 *** | (0.827) | |||

| 7. Collectivism | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.203 | 0.238 * | (0.819) | ||

| 8. Masculinity | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.127 * | 0.181 * | 0.124 * | (0.873) | |

| 9. Career satisfaction | 0.12 * | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.09 * | 0.412 ** | 0.527 *** | 0.148 * | 0.202 * | (0.924) |

| Mean | 33.78 | 0.68 | 4.72 | 14.34 | 4.07 | 3.97 | 3.19 | 3.26 | 4.19 |

| SD | 5.79 | 0.39 | 1.08 | 7.94 | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.26 |

| Standardised Coefficient | Confidence Intervals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | R2 | Lower Limit | Upper Limit |

| CSR perceptions → organisational pride → career satisfaction | 0.52 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.72 ** | 0.43 | 0.04 | 0.22 |

| Organisational Pride | Career Satisfaction | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | ||||||

| Variables | β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t |

| Age | 0.05 | 0.47 | 0.04 | 0.56 | 0.003 | 0.06 | 0.002 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.08 |

| Gender | −0.05 | −2.29 * | −0.04 | −2.12 * | 0.03 | 0.77 | 0.03 | 0.92 | 0.04 | 1.21 |

| Industry type | 0.04 | 0.57 | −0.03 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.34 | 0.01 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.35 |

| Tenure | 0.08 | 3.39 * | 0.08 | 3.37 * | −0.03 | −0.16 | −0.03 | −0.12 | −0.03 | −0.27 |

| Perceived CSR | 0.384 | 13.28 ** | 0.462 | 14.38 ** | 0.574 | 21.98 ** | 0.562 | 19.74 ** | 0.377 | 16.75 ** |

| Collectivism | 0.157 | 4.47 ** | 0.168 | 5.27 ** | 0.127 | 2.68 * | 0.07 | 2.03 * | 0.02 | 1.97 * |

| Masculinity | 0.186 | 5.68 *** | 0.194 | 5.83 *** | 0.212 | 6.58 ** | 0.185 | 6.02 ** | 0.173 | 5.17 ** |

| Perceived CSR X Collectivism | 0.06 | 2.27 ** | 0.05 | 2.14 * | 0.02 | 1.53 | ||||

| Perceived CSR X Masculinity | −0.05 | −2.18 ** | −0.04 | −1.36 | −0.03 | −1.39 | ||||

| Organisational pride | 0.258 | 7.16 *** | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.497 | 0.521 | 0.374 | 0.428 | 0.473 | |||||

| ΔR2 | 0.024 | 0.054 | 0.045 | |||||||

| F-value | 76.39 ** | 61.32 ** | 86.95 *** | 77.29 *** | 71.88 *** | |||||

| Career Satisfaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collectivism (Moderator) | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LL (95% CI) | Boot UL (95% CI) |

| −1 SD (−2.38) | 0.11 | 0.009 | 0.05 | 0.12 |

| Mean (0.00) | 0.09 | 0.014 | 0.07 | 0.11 |

| +1 SD (2.38) | 0.08 | 0.013 | 0.06 | 0.13 |

| Index of moderated mediation | 0.069 | 0.012 | 0.07 | 0.19 |

| Masculinity (moderator) | ||||

| −1 SD (−2.38) | 0.08 | 0.013 | 0.14 | 0.21 |

| Mean (0.00) | 0.07 | 0.014 | 0.11 | 0.17 |

| +1 SD (2.38) | 0.02 | 0.006 | 0.05 | 0.15 |

| Index of moderated mediation | −0.017 | 0.004 | −0.018 | −0.007 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mansour, M.; Alaghbari, M.A.; Beshr, B.; Al-Ghazali, B.M. Perceived CSR on Career Satisfaction: A Moderated Mediation Model of Cultural Orientation (Collectivism and Masculinity) and Organisational Pride. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5288. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065288

Mansour M, Alaghbari MA, Beshr B, Al-Ghazali BM. Perceived CSR on Career Satisfaction: A Moderated Mediation Model of Cultural Orientation (Collectivism and Masculinity) and Organisational Pride. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):5288. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065288

Chicago/Turabian StyleMansour, Mourad, Mohammed Abdulrazzaq Alaghbari, Baligh Beshr, and Basheer M. Al-Ghazali. 2023. "Perceived CSR on Career Satisfaction: A Moderated Mediation Model of Cultural Orientation (Collectivism and Masculinity) and Organisational Pride" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 5288. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065288

APA StyleMansour, M., Alaghbari, M. A., Beshr, B., & Al-Ghazali, B. M. (2023). Perceived CSR on Career Satisfaction: A Moderated Mediation Model of Cultural Orientation (Collectivism and Masculinity) and Organisational Pride. Sustainability, 15(6), 5288. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065288