Sustainability of Taiwanese SME Family Businesses in the Succession Decision-Making Agenda

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Related Theories

2.2. Influential Factors

2.2.1. Individual Factors

2.2.2. Interpersonal Factors

2.2.3. Organizational Factors

2.2.4. Environmental Factors

3. Methodology

3.1. Two-Round Delphi Method

3.2. DEMATEL Method

3.3. Importance–Performance Analysis

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Findings Result of Delphi Method

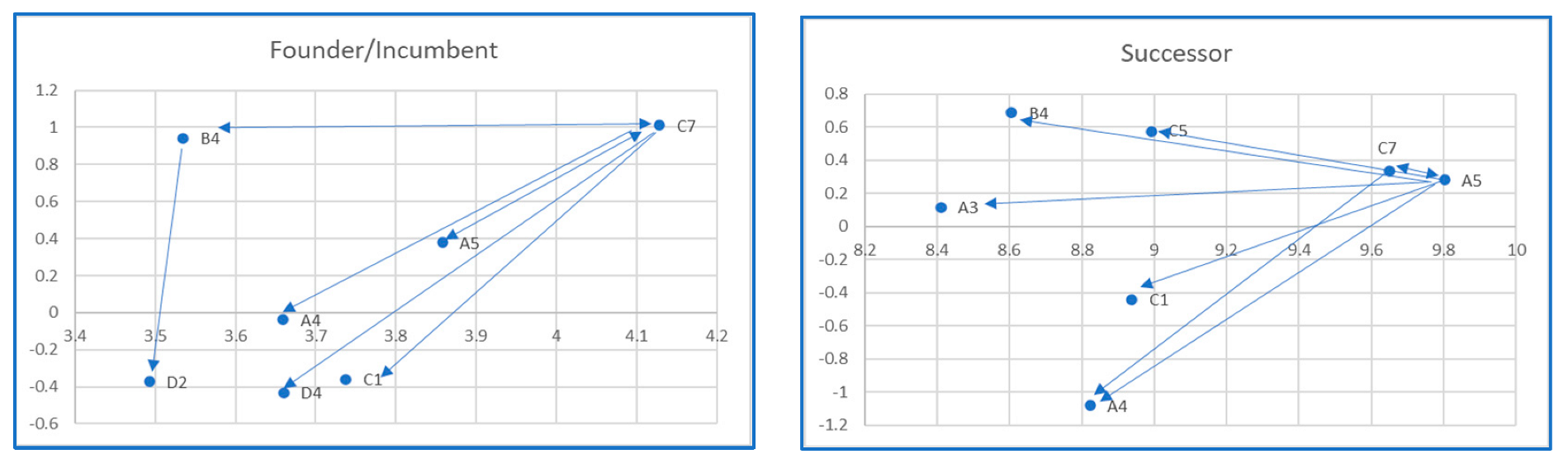

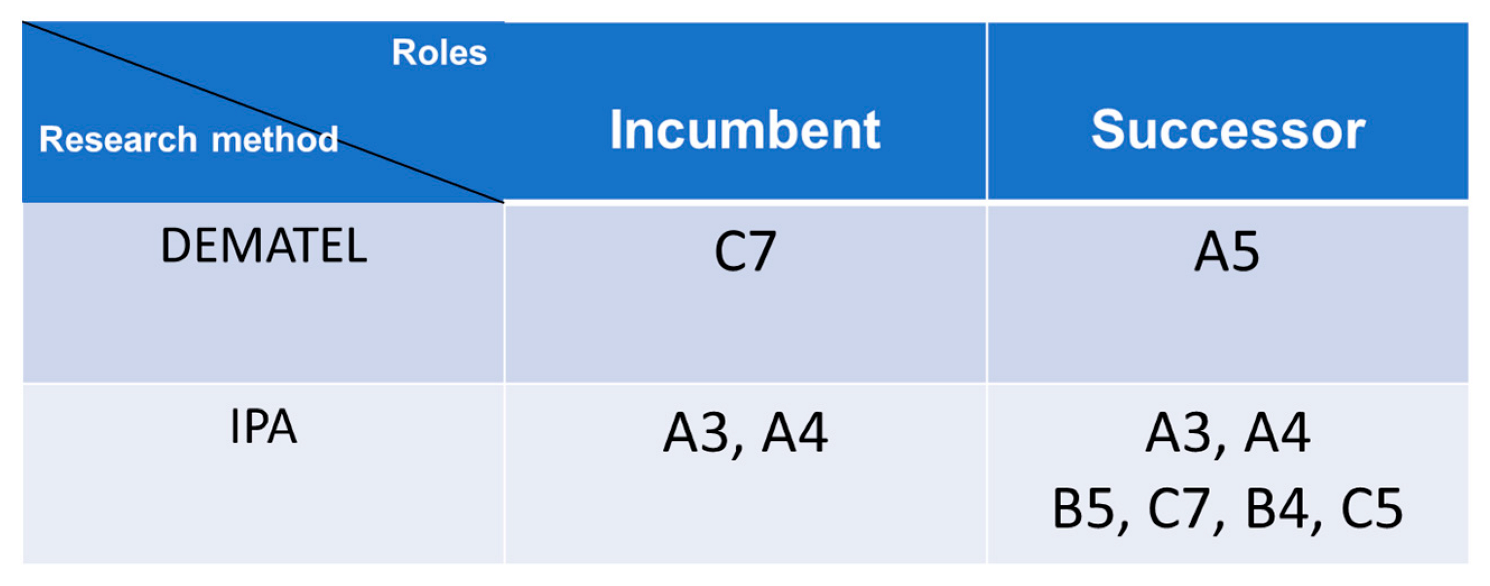

4.2. Findings Result of DEMATEL Method

4.3. Findings Result of IPA

5. Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Implication

5.3. Suggestions

5.4. Limitationand Future. Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baron, J.; Lachenauer, R. Do Most Family Businesses Really Fail by the Third Generation? 2021. Available online: https://hbr.org/2021/07/do-most-family-businesses-really-fail-by-the-third-generation (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Yeh, Y.H.; Liao, C.C. The impact of product market competition and internal corporate governance on family succession. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2020, 62, 101346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwan Institute of Directors. Family Governance Review 20. 2016. Available online: https://twiod.org/index.php/tw/?option=com_sppagebuilder&view=page&id=82 (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Villalonga, B.; Amit, R. How do family ownership, control and management affect firm value? J. Financ. Econ. 2006, 80, 385–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.L. Growing the family business: Special challenges and best practices. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1997, 10, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.S.; Harveston, P.D. The phenomenon of substantive conflict in the family firm: A cross-generational study. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2001, 39, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. An overview of the field of family business studies: Current status and directions for the future. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2004, 17, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, S.; Venter, E.; Boshoff, C. The influence of family and non-family stakeholders on family business success. S. Afr. J. Entrep. Small Bus. Manag. 2010, 3, 32–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaroni, F.M.; Sentuti, A. Family business succession and external advisors: The relevance of ‘soft’ issues. Small Enterp. Res. 2017, 24, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C. Upper echelons theory: An update. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.J.; Shim, J. When does transitioning from family to professional management improve firm performance? Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1297–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, H.; Coviello, N.; Ranaweera, C. When is top management team heterogeneity beneficial for product exploration? Understanding the role of institutional pressures. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldkirch, M.; Nordqvist, M. Finding Benevolence in Family Firms: The Case of Stewardship Theory; The Routledge Companion to Family Business; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 431–444. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, J.L.; Kostova, T.; Dirks, K.T. Toward a theory of psychological ownership in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, S.D.; Dyck, B. Agency, stewardship, and the universal-family firm: A qualitative historical analysis. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2015, 28, 312–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Breton-Miller, I.; Miller, D. The arts and family business: Linking family business resources and performance to industry characteristics. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 1349–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; Jensen, M.C. Agency problems and residual claims. J. Law Econ. 1983, 26, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, C.M. Agency Theory: Definition, Examples of Relationships, and Disputes 2021. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/agencytheory.asp (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and capital structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammerlander, N. I want this firm to be in good hands: Emotional pricing of resigning entrepreneurs. Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 34, 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M.; Johnson, S.; Samphantharak, K.; Schoar, A. Mixing family with business: A study of Thai business groups and the families behind them. J. Financ. Econ. 2008, 88, 466–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handler, W.C. Succession in family business: A review of the research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1994, 7, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrelli, V.; Rovelli, P.; Benedetti, C.; Überbacher, R.; De Massis, A. Generations in family business: A multifield review and future research agenda. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2022, 35, 15–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.L.; Harris, R.; Miles, A. Mentoring in sports coaching: A review of the literature. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2009, 14, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehrer, A.; Leiß, G. Intergenerational communication barriers and pitfalls of business families in transition: A qualitative action research approach. Int. J. 2020, 25, 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, E.; Van der Merwe, S.; Farrington, S. The impact of selected stakeholders on family business continuity and family harmony. S. Afr. Bus. Rev. 2012, 16, 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- Malinen, P. Problems in transfer of business experienced by Finnish entrepreneurs. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2004, 11, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, L.; Shariff, M.N.M.; Arshad, D.A. Attitude toward conflict and family business succession. J. Bus. Manag. Account. 2020, 6, 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, U.; Forsgren, M.; Holm, U. The strategic impact of external networks: Subsidiary performance and competence development in the multinational corporation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 979–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansberg, I. Succeeding Generations: Realizing the Dream of Families in Business; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, M.V. Does a Family-First Philosophy Affect Family Business Profitability? An Analysis of Family Businesses in the Midwest. Doctoral Thesis, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2015. Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_theses/498 (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Naveen, L. Organizational complexity and succession planning. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2006, 41, 661–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daspit, J.J.; Chrisman, J.J.; Ashton, T.; Evangelopoulos, N. Family firm heterogeneity: A definition, common themes, scholarly progress, and directions forward. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2021, 34, 296–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vola, P.; Songini, L. The role of professionalization and managerialization in family business succession. Mater. Corros.—Werkst. Und Korros. 2015, 1, 9–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell, W.J. Effective Succession Planning: Ensuring Leadership Continuity and Building Talent from Within, 3rd ed.; American Management Association: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Umans, I.; Lybaert, N.; Steijvers, T.; Voordeckers, W. The influence of transgenerational succession intentions on the succession planning process: The moderating role of high-quality relationships. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2021, 12, 100269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillebrand, S. Innovation in family firms: A generational perspective. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2019, 9, 126–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlömer-Laufen, N.; Rauch, A. Internal and external successions in family firms: A meta-analysis. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2022, 12, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincencová, E.; Hodinková, M.; Horák, R. The tax effects of the family business succession. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 34, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geroski, P.; Machin, S.; Van Reenen, J. The profitability of innovating firms. Rand J. Econ. 1993, 24, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, A.; Kammerlander, N.; Enders, A. The family innovator’s dilemma: How family influence affects the adoption of discontinuous technologies by incumbent firms. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2013, 38, 418–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundström, C.; Öberg, C.; Rönnbäck, A.Ö. Family-owned manufacturing SMEs and innovativeness: A comparison between within-family successions and external takeovers. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2012, 3, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Massis, A.; Chua, J.H.; Chrisman, J.J. Factors preventing intra-family succession. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2008, 21, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansikas, J.; Kuhmonen, T. Family business succession: Evolutionary economics approach. J. Enterprising Cult. 2008, 16, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbie, I.H. Concepts and measurements of industrial complexity: A state-of-the-art survey. Int. J. Ind. Syst. Eng. 2012, 12, 42–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giachetti, R.E.; Martinez, L.D.; Sáenz, O.A.; Chen, C.S. Analysis of the structural measures of flexibility and agility using a measurement theoretical framework. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2003, 86, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Steinwender, C. Import competition, heterogeneous preferences of managers, and productivity. J. Int. Econ. 2021, 133, 103533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morck, R.K.; Stangeland, D.A.; Yeung, B. Inherited wealth, corporate control, and economic growth: The Canadian disease? Concentrated Corporate Ownership; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000; pp. 319–372. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, A.J.; Marchildon, G.P. Using the Delphi method for qualitative, participatory action research in health leadership. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2014, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, S.A.; Lummus, R.R.; Vokurka, R.J.; Burns, L.J.; Sandor, J. Mapping the future of supply chain management: A Delphi study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2009, 47, 4629–4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Pippon-Young, L. The Delphi method. Nurs. Res. 2009, 46, 116–118. [Google Scholar]

- Quyên, Đ.T.N. Developing university governance indicators and their weighting system using a modified Delphi method. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 141, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibe, M.; Skutsch, M.; Schofer, J. Experiments in Delphi methodology. In The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications; Linstone, H.A., Turoff, M., Eds.; Addison-Wesley: London, UK, 1975; pp. 263–287. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.Y.; Hsu, P.Y.; Sheen, G.J. A fuzzy-based decision-making procedure for data warehouse system selection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2007, 32, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y. An integrative conceptual framework for sustainable successions in family businesses: The case of Taiwan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, M.; Khan, F.; Abbassi, R.; Rusli, R. Improved DEMATEL methodology for effective safety management decision-making. Saf. Sci. 2020, 127, 104705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martilla, J.A.; James, J.C. Importance-performance analysis. J. Mark. 1977, 41, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alase, A. The interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): A guide to a good qualitative research approach. Int. J. Educ. Lit. Stud. 2017, 5, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Expert | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | QDS1 | Avg | Sum | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0.375 | 4.7 | 56 | 5 |

| A2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3.8 | 46 | 19 |

| A3 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 0.625 | 4.3 | 52 | 9 |

| A4 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 0.25 | 5.2 | 62 | 1 |

| A5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 0.25 | 4.9 | 59 | 3 |

| A6 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3.0 | 36 | 27 |

| A7 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 0.625 | 3.6 | 43 | 23 |

| A8 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 0.25 | 3.2 | 38 | 26 |

| B1 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 0.375 | 4.5 | 54 | 7 |

| B2 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0.25 | 5.0 | 60 | 2 |

| B3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 0.75 | 4.0 | 48 | 16 |

| B4 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 0.75 | 4.2 | 50 | 13 |

| B5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 0.5 | 4.6 | 55 | 6 |

| B6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 0.5 | 4.4 | 53 | 8 |

| C1 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0.375 | 4.8 | 58 | 4 |

| C2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 0.625 | 3.8 | 46 | 19 |

| C3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 0.375 | 3.9 | 47 | 18 |

| C4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 0.375 | 4.2 | 50 | 13 |

| C5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 0.25 | 4.3 | 51 | 12 |

| C6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 | 3.8 | 45 | 21 |

| C7 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 0.375 | 4.3 | 52 | 9 |

| D1 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 3.4 | 41 | 25 |

| D2 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 0.5 | 4.3 | 52 | 9 |

| D3 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 0.875 | 4.0 | 48 | 16 |

| D4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 0.375 | 4.2 | 50 | 13 |

| D5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 0.625 | 3.8 | 45 | 21 |

| D6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 0.625 | 3.6 | 43 | 23 |

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 | F9 | F10 | F11 | F12 | F13 | F14 | F15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.87 | 0.80 | 1.53 | 1.00 | 1.20 | 0.53 | 1.13 | 0.60 | 0.87 | 1.20 | 0.47 | 0.60 |

| F2 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 1.87 | 1.20 | 1.93 | 1.53 | 1.40 | 1.73 | 1.27 | 1.60 | 0.73 | 1.07 | 1.60 | 1.80 | 1.67 |

| F3 | 1.73 | 1.67 | 0.00 | 1.53 | 1.33 | 0.87 | 1.67 | 1.53 | 1.73 | 1.53 | 1.80 | 1.60 | 2.00 | 2.47 | 2.27 |

| F4 | 2.80 | 2.00 | 2.20 | 0.00 | 2.40 | 2.60 | 2.20 | 2.40 | 1.40 | 2.47 | 1.47 | 1.33 | 1.80 | 1.73 | 1.87 |

| F5 | 1.47 | 1.67 | 0.93 | 1.33 | 0.00 | 2.20 | 1.07 | 2.20 | 0.87 | 1.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 1.53 | 0.60 | 0.87 |

| B6 | 1.53 | 1.73 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 2.13 | 0.00 | 0.87 | 2.27 | 0.67 | 1.53 | 0.60 | 0.27 | 1.13 | 0.33 | 0.47 |

| F7 | 2.53 | 1.93 | 2.67 | 3.07 | 1.93 | 1.60 | 0.00 | 1.73 | 1.27 | 2.40 | 2.20 | 1.87 | 1.93 | 2.33 | 2.33 |

| F8 | 1.53 | 1.73 | 1.60 | 1.67 | 1.80 | 2.27 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.93 | 1.07 | 1.40 | 1.20 | 0.73 | 0.60 |

| F9 | 2.07 | 1.47 | 1.47 | 2.40 | 1.47 | 1.13 | 1.27 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 1.93 | 0.93 | 0.33 | 1.33 | 2.47 | 2.67 |

| F10 | 1.93 | 0.80 | 2.07 | 1.27 | 1.13 | 1.47 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 1.47 | 0.00 | 1.20 | 2.07 | 1.53 | 2.73 | 3.33 |

| F11 | 1.00 | 0.53 | 1.13 | 0.87 | 0.73 | 0.53 | 0.73 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 1.80 | 0.00 | 2.33 | 1.27 | 2.20 | 1.73 |

| F12 | 2.33 | 1.33 | 1.80 | 1.73 | 1.40 | 0.40 | 1.73 | 1.27 | 0.60 | 2.20 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 1.20 | 2.40 | 2.60 |

| F13 | 3.07 | 2.73 | 2.67 | 2.93 | 2.53 | 1.93 | 2.40 | 2.13 | 1.47 | 2.67 | 2.53 | 1.93 | 0.00 | 2.53 | 3.20 |

| F14 | 1.67 | 0.80 | 2.27 | 1.93 | 0.53 | 0.07 | 0.47 | 0.33 | 0.93 | 2.60 | 2.13 | 2.20 | 1.40 | 0.00 | 2.87 |

| F15 | 1.53 | 0.60 | 2.80 | 1.73 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 1.33 | 2.93 | 1.67 | 2.27 | 1.33 | 2.73 | 0.00 |

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | S9 | S10 | S11 | S12 | S13 | S14 | S15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 2.13 | 3.20 | 2.73 | 2.73 | 2.87 | 2.80 | 1.40 | 2.60 | 1.93 | 2.13 | 2.60 | 1.60 | 1.93 |

| S2 | 2.33 | 0.00 | 3.40 | 3.13 | 2.80 | 1.93 | 2.67 | 2.93 | 1.60 | 2.20 | 1.47 | 2.80 | 2.80 | 2.60 | 2.47 |

| S3 | 1.80 | 2.67 | 0.00 | 2.87 | 2.07 | 1.40 | 1.87 | 1.80 | 2.20 | 2.93 | 2.07 | 2.67 | 2.33 | 2.47 | 2.73 |

| S4 | 3.20 | 3.80 | 3.53 | 0.00 | 3.40 | 3.47 | 3.27 | 2.60 | 1.60 | 3.80 | 1.73 | 3.07 | 3.53 | 2.33 | 2.73 |

| S5 | 2.67 | 2.93 | 2.60 | 3.20 | 0.00 | 3.07 | 2.47 | 2.80 | 1.40 | 2.47 | 1.13 | 1.80 | 2.60 | 1.27 | 1.27 |

| S6 | 2.47 | 3.07 | 3.13 | 2.07 | 2.53 | 0.00 | 2.33 | 2.93 | 1.07 | 2.13 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 2.07 | 0.47 | 1.00 |

| S7 | 2.80 | 3.13 | 3.00 | 3.33 | 2.27 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 2.33 | 1.40 | 3.47 | 2.80 | 3.07 | 3.47 | 2.60 | 2.80 |

| S8 | 2.00 | 2.73 | 2.60 | 2.47 | 2.60 | 2.67 | 2.20 | 0.00 | 0.53 | 2.20 | 1.73 | 2.80 | 2.93 | 1.53 | 1.73 |

| S9 | 2.13 | 2.60 | 2.00 | 2.60 | 2.33 | 1.40 | 1.87 | 1.87 | 0.00 | 2.40 | 1.07 | 1.53 | 2.33 | 2.53 | 2.87 |

| S10 | 2.40 | 1.87 | 3.33 | 2.93 | 1.60 | 1.73 | 2.40 | 2.40 | 2.20 | 0.00 | 1.73 | 2.73 | 3.33 | 3.13 | 3.33 |

| S11 | 1.67 | 1.47 | 2.00 | 1.67 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 1.60 | 1.80 | 1.20 | 2.07 | 0.00 | 2.40 | 2.40 | 2.73 | 2.87 |

| S12 | 2.67 | 2.73 | 3.47 | 3.20 | 2.60 | 1.93 | 2.87 | 2.67 | 1.40 | 3.40 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 3.40 | 3.27 | 3.33 |

| S13 | 3.53 | 3.00 | 3.53 | 3.53 | 3.00 | 2.60 | 3.13 | 2.73 | 1.20 | 3.33 | 3.13 | 3.07 | 0.00 | 2.80 | 3.27 |

| S14 | 2.67 | 1.33 | 3.47 | 2.93 | 1.27 | 0.67 | 1.53 | 0.53 | 2.07 | 2.87 | 2.67 | 2.67 | 2.40 | 0.00 | 3.60 |

| S15 | 1.60 | 1.20 | 3.00 | 2.53 | 0.93 | 0.73 | 1.53 | 0.53 | 1.87 | 3.00 | 2.53 | 2.73 | 2.60 | 3.47 | 0.00 |

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 | F9 | F10 | F11 | F12 | F13 | F14 | F15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| F2 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| F3 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| F4 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.16 |

| F5 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| B6 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| F7 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| F8 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| F9 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.16 |

| F10 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.18 |

| F11 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.12 |

| F12 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.16 |

| F13 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.22 |

| F14 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.16 |

| F15 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.09 |

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | S9 | S10 | S11 | S12 | S13 | S14 | S15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.27 |

| S2 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.19 | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.30 |

| S3 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.29 |

| S4 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.21 | 0.40 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.35 |

| S5 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.25 |

| S6 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.21 |

| S7 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.37 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.31 | 0.33 |

| S8 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.29 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.26 |

| S9 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.28 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.27 |

| S10 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.32 |

| S11 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.25 |

| S12 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.38 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.35 |

| S13 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.39 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.36 |

| S14 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.30 |

| S15 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.21 |

| Di | Ri | Pi | Ei | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Incumbent’s age and health condition | 0.9592 | 2.0348 | 2.9940 | −1.0756 |

| A3 | Incumbent’s satisfaction with their successor | 1.6133 | 1.4903 | 3.1036 | 0.1229 |

| A4 | Successor’s competence | 1.8113 | 1.8483 | 3.6596 | 0.0370 |

| A5 | Successor’s willingness | 2.1189 | 1.7388 | 3.8577 | −0.3800 |

| B1 | Relationship between generation | 1.2827 | 1.5374 | 2.8201 | −0.2546 |

| B2 | Family harmony | 1.0849 | 1.3945 | 2.4794 | −0.3097 |

| B4 | Management transfer | 2.2383 | 1.2964 | 3.5347 | 0.9418 |

| B5 | Conflict management | 1.3484 | 1.4396 | 2.7880 | −0.0912 |

| B6 | Founder social capital | 1.6537 | 1.1305 | 2.7842 | 0.5232 |

| C1 | Profitability and financial situation | 1.6888 | 2.0482 | 3.7371 | −0.3594 |

| C4 | Complexity of the organization | 1.2472 | 1.4816 | 2.7288 | −0.2344 |

| C5 | Senior managers | 1.7380 | 1.5533 | 3.2914 | 0.1847 |

| C7 | Succession plan | 2.5708 | 1.5580 | 4.1287 | 1.0128 |

| D2 | Industrial science and technology changes | 1.5601 | 1.9324 | 3.4925 | −0.3723 |

| D4 | Industrial life-cycle | 1.6143 | 2.0457 | 3.6600 | −0.4313 |

| D | R | Pi | Ei | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Incumbent’s age and health condition | 3.9717 | 4.0987 | 8.0704 | −0.1271 |

| A3 | Incumbent’s satisfaction with their successor | 4.2632 | 4.1480 | 8.4112 | 0.1151 |

| A4 | Successor’s competence | 3.8711 | 4.9527 | 8.8238 | −1.0816 |

| A5 | Successor’s willingness | 5.0413 | 4.7603 | 9.8017 | 0.2810 |

| B1 | Relationship between generation | 3.8721 | 3.7622 | 7.6343 | 0.1099 |

| B2 | Family harmony | 3.3124 | 3.3373 | 6.6497 | −0.0249 |

| B4 | Management transfer | 4.6465 | 3.9592 | 8.6056 | 0.6873 |

| B5 | Conflict management | 3.7657 | 3.7079 | 7.4735 | 0.0578 |

| B6 | Founder social capital | 3.5944 | 2.6308 | 6.2252 | 0.9636 |

| C1 | Profitability and financial situation | 4.2484 | 4.6902 | 8.9386 | −0.4418 |

| C4 | Complexity of the organization | 3.1455 | 3.4235 | 6.5690 | −0.2781 |

| C5 | Senior managers | 4.7817 | 4.2118 | 8.9935 | 0.5699 |

| C7 | Succession plan | 4.9918 | 4.6580 | 9.6498 | 0.3338 |

| D2 | Industrial science and technology changes | 3.7224 | 4.0023 | 7.7247 | −0.2799 |

| D4 | Industrial life-cycle | 3.463 | 4.348 | 7.811 | −0.885 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, C.-W.; Chen, H.C.; Peng, C.L.; Chen, S.H. Sustainability of Taiwanese SME Family Businesses in the Succession Decision-Making Agenda. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021237

Lee C-W, Chen HC, Peng CL, Chen SH. Sustainability of Taiwanese SME Family Businesses in the Succession Decision-Making Agenda. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):1237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021237

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Cheng-Wen, Hsiao Chuan Chen, Choong Leng Peng, and Shu Hui Chen. 2023. "Sustainability of Taiwanese SME Family Businesses in the Succession Decision-Making Agenda" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 1237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021237

APA StyleLee, C.-W., Chen, H. C., Peng, C. L., & Chen, S. H. (2023). Sustainability of Taiwanese SME Family Businesses in the Succession Decision-Making Agenda. Sustainability, 15(2), 1237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021237