Abstract

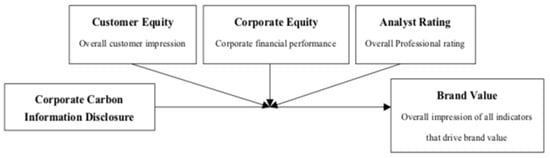

Could the corporate carbon information disclosure strategy influence a firm’s brand value, and how does corporate carbon information affect it? Previous research mainly examines the impact of ESG information disclosure on firm value and other financial indicators, but little research has focused on the effect of carbon information on brand value. This paper focuses on the influence of corporate carbon information disclosure on brand value, and we find that it positively impacts corporate brand value. In addition, when a company chooses to adopt a more quantitative and diverse carbon information strategy, it increases its brand value. We also examine the potential mechanisms involved in how corporate carbon information disclosure influences brand value. We focus on three types of factor: analyst rating, customer attitude, and corporate financial performance, and find that higher analyst forecasts and positive customer attitudes have a positive impact on the association between the carbon information strategy and corporate brand value. In contrast, corporate financial performance provides only weak evidence. These results are consistent with demands by users for more precise guidelines from regulators and standard-setters for measuring and disclosing carbon-related information.

1. Introduction

Within the context of a global commitment to carbon reduction, such as the Paris Agreement and the Kyoto Protocol, governments and institutional investors have increasingly incorporated carbon emission information into their investment recommendations [1]. Truthful voluntary carbon emission disclosures could convey nonfinancial information to investors, reduce the cost of carbon information searches, and increase firm value [2]. However, there are few studies on the relationship between carbon emission information disclosure and corporate brand value. Considering the concerns expressed by investors, customers, standard setters, and other stakeholders about the costs and benefits of carbon disclosure, we estimate the impact of voluntary carbon disclosure on brand value.

A corporate carbon information disclosure strategy means that corporations choose whether to disclose carbon information and what quantity to disclose. Corporate carbon information disclosure is voluntary, but independent third parties also create pressure to disclose, which is not mandated in China. The representative Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) questionnaire points out that the content of corporate carbon information should include different perspectives: managers’ understanding of risks and opportunities related to climate change, calculation of GHG emissions and GHG emission reduction, and the corporate company’s governance measures to deal with climate change, and so on. Our study classifies the corporate carbon information disclosure strategy according to these carbon information disclosure standards. We identify corporate carbon information disclosure content from the corporate carbon management strategy, corporate carbon management actions, and corporate carbon measurements. Additionally, we classify these into 13 categories: opportunities and risks related to low-carbon development, carbon reduction quantitative targets, carbon reduction qualitative targets, carbon reduction strategy, carbon reduction institution and system, carbon trade, low-carbon culture, government recognition of carbon reduction, low-carbon resource input and recovery, carbon reduction performance, carbon accounting standard, and carbon accounting.

To illustrate the corporate carbon information strategy, consider the example of China Southern Airlines and Beijing Gehua Cable Television Network. China Southern Airlines is a corporate company with the most significant aircraft, the most developed route network, and China’s most significant annual passenger volume. It was founded in 1991 and trades on the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The company’s annual reports have historically been similar over time. In contrast, Beijing Gehua Cable Television Network was listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange in 2001. It is the only network operator responsible for the construction, development, operation, management, and maintenance of cable broadcasting and television networks in Beijing. The company has also released annual reports historically. Table 1 shows some of these two corporate companies’ carbon information disclosure headlines in 2017.

Table 1.

Carbon information disclosure of example companies.

A brand is a critical asset of enterprise value [3]. The future of the consumer market belongs to the companies with the strongest brands, and customer brand engagement is an essential mediator between social media marketing and brand awareness [4]. Brand enables enterprise to add symbolic meaning to goods and services, but the end customer ultimately decides what the brand means to them. Given this reality, firms invest much time and effort in supporting their brand image through strategic brand concept management [5]. Enterprises traditionally manage their brand by targeting or using advertising and other promotional messages to have an effect on customers’ minds [6]. Enterprises deliver positive information to customers and thus generate a positive brand impression on them. With the development of social media, consumers are more likely to be affected by various information and have a more complex impression of enterprises in terms of their brand. In the context of global carbon emission reduction targets, customers pay increasing attention to corporate carbon information, which affects customers’ impression of the brand.

Previous studies have demonstrated the correlation between corporate ESG (Environment, Society, and Government) information and brand value. Saini N et al. (2022) [7] show that ESG is a management method to conduct business ethically in order to balance environmental, social, and economic goals, rather than focusing solely on economic results. Companies are tasked with maximizing profits while ensuring that their products and operations do not damage the environment. ESG metrics and reporting provide essential information for investors and regulators [8]. Therefore, when enterprises disclose more ESG information to customers, a positive brand impression will be generated. These furtherly affect the brand value. As a part of the ESG, carbon information reflects a company’s efforts to efficiently reduce their carbon emissions, which is increasingly important in the context of global carbon emission reduction. Corporate disclosure of carbon information is related to a low-carbon strategy, carbon emission reduction accounting, carbon emission reduction management, and global climate governance. Consumers are more likely to buy from companies that use ESG as a business model, especially when there is a high match between the company and the ESG business [9]. Therefore, as part of ESG information, the disclosed carbon information could also affect the corporate company’s brand value.

Our study contributes to the literature on company brands in four distinct and important ways. First, extant research examines the impact of ESG information disclosure on enterprise value and other financial indicators (i.e., stock price, debt cost, equity cost, revenue, cash flow). Nicola Raimo (2021) [10] shows the negative effect of ESG disclosure on the cost of debt financing. Companies with greater levels of transparency in the dissemination of ESG information benefit from accessing third-party financial resources. In contrast, we focus on carbon information disclosure, which is a voluntary disclosure process for corporate companies in China. Our study provides empirical evidence concerning the influence of corporate carbon information disclosure on brand value assessments. Second, we examine the relation between the carbon information disclosure strategy and brand value for high-carbon industries and low-carbon industries, because of the great industry heterogeneity of carbon emissions. Third, we further explore the potential mechanism of the corporate carbon information disclosure strategy on brand value. Fourth, we explore how analysts, customers, and corporate financial performances mediate the relationship between corporate carbon information and brand value.

2. Related Research and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Brand Value Creation

The literature on marketing conceptualizes brands from three theoretical perspectives: enterprise, society, and consumer [11]. First, the corporate perspective views the brand as an asset and examines the various functions by which the brand serves the enterprise strategically and financially. Brand identity is estimated in the following ways: brand positioning, target positioning, launch, and growth [12]. He J and Calder B.J. (2020) [13] indicate that financial strength is one of the main sources of a company’s brand value, which is gained by differentiating the brand from its competitors. Thus, the impact of brand creation is usually estimated by the company’s stock market valuation [14,15,16,17].

Second, the society perspective places the brand within a cultural framework, which relates to how it influences individual consumers directly or indirectly through social forces, structures, and commercial and non-commercial entities. O’Guinn et al. (2018) [18] find that brands develop or reshape themselves dynamically in order to create meaning in society, rather than being passive representations. In general, the literature utilizing this perspective focuses on how iconic brands significantly infuse cultural characteristics and then influence consumer behavior and market creation [19]. This kind of literature focuses on brand groups, regardless of geographical restrictions. Muniz and O’Guinn (2001) [18] show that admirers of a brand have a community distinction in their association with other brands, including a sense of variety, ritual, tradition, and moral obligation.

Third, the consumer perspective looks at brands from a signal and psychological perspective. Qing T and Haiying D (2021) [20] demonstrate that consumers tend to know the quality and intent of the brand in terms of information asymmetry. The research of Keller (1993) [21] indicates that consumer psychology and signal theory transfer achievement information such as brand type, favorability, strength, and uniqueness to consumers in order to impress on their minds. Therefore, the key concepts of brand value are conceptualized and measured from the perspective of consumers’ brand knowledge, brand image, and brand awareness [22].

In our recent literature review, we found that consumers tend to seek innovative and financially successful brands that contribute to the collective environmental, social, and economic good; this is known as ESG information. The consumer perspective of a firm’s product and financial performance provides a lens to examine brand value creation. Our research study is embedded in this consumer view of signaling theory.

2.2. The Influence of Carbon Information Disclosure on Brand Value

The American Marketing Association defines a brand as “a name, term, design, symbol, or any other feature that distinguishes one seller’s goods or services from those of other sellers.” Zhou G et al. (2022) [23] think that a brand is a sign that a company discloses the hidden qualities of its products that are inaccessible. In other words, consumers prefer to buy it when the product quality is higher than others. Accordingly, the function of a brand is to reduce the perceived risks. Brand value is created when customers perceive the importance, confidence, empathy, richness, and attractiveness of a company’s brand image compared to its competitors. In addition, brand value is consistent with brand equity, which is both tangible and intangible. Aaker (1992) [24] indicates that brand equity achievement can promote loyalty, awareness, quality, leadership, and association, thus generating high corporate value.

Previous studies have focused on whether consumers associate functional product achievements with brand value [25]. This literature examines the characteristics of brand innovation, practicality, and desirability as prerequisites for the specific context of brand value [26]. González-Mansilla (2019) [27] proves that brand equity and its perceived value are positively linked with customer satisfaction. In addition, the customer perception process of value co-creation positively impacts brand equity. France C et al. (2020) [28] consider the role of customer participation in a range of active customer behaviors, including development, feedback and advocacy. In recent years, in the context of global carbon emission reduction, enterprises have been increasingly willing to invest in low-carbon governance, while constantly pursuing a premium reputation and brand value. Low-carbon governance means that managers conduct their business to reduce carbon emissions rather than focusing solely on economic targets. The task for companies is to maximize profits while ensuring that they take governance measures to tackle climate change. Arvidsson S and Dumay J (2022) [29] show that consumers are more likely to buy from companies that use ESG as a business model, especially when there is a high degree of fit between the company and the ESG business. Carbon reduction governance is also part of ESG governance, so we hypothesize that it could also influence consumer behavior.

There is research on ESG information as a business model for brand valuation but there is little about carbon information. As carbon information belongs to the environment section, the research on customer ESG information also has significance for our research. Landrum (2017) [30] states that 66% of consumers are willing to pay more for brands that invest in ESG and 81% of millennials expect their favorite companies to publicly declare their corporate citizenship. In addition, Naidoo and Abratt (2018) [31] show that social brands have social intentions, which determine the value of the brand in terms of society. There is also research that proves the indirect value relationship of the ESG brand. For example, country differences affect sustainability and thus brand valuation [32,33]. Sierra et al. (2017) [34] indicate that customer-perceived ethicality has a positive, indirect impact on brand equity, through the mediators of brand effect and perceived quality. Lee (2016) [26] points out that empathy increases consumers’ willingness to pay for “pro-social” products and reduces their price sensitivity. Overall, these studies suggest that the consumer has more loyalty to an ESG brand than to its non-ESG competitors, as quality and value are impacted to a greater extent when companies invest in ESG.

In addition, there are few studies on the impact of carbon information disclosure on brand value. In 2005, the Kyoto Protocol forced developed countries to reduce their emissions. From 2010 to 2021, it stated that the total world’s carbon emission had increased to 33884.06 megatons, over 43.43% more than that in 2000. In addition, the growth rate rose from 2.4% to 5.6%. This made developed countries pay more attention to the carbon footprint of products and try to choose low-carbon products in the supply chain. As a result, Dhaliwal et al. (2011) [35] show that companies can make a good impression on these countries through good carbon performance disclosure. This suggests that greater transparency is a key part of building credibility. Consistent with these views, we propose the following hypothesis regarding the reputational impact of carbon disclosure.

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

A firm’s brand value is positively associated with carbon information disclosure.

2.3. How Does the Carbon Information Disclosure Influence Brand Value?

2.3.1. Carbon Information, Customer and Brand Value

With the growth of the interconnected environment, consumers can also rely on independent evaluators, reviewers, their peers, and influencers who rate businesses through social media networks and communicate with other consumers to assess and affect brand valuations [36]. This brings us to the second question of our study: How can companies share and communicate carbon information and achievements for brand valuation? To explain this, we explore how voluntary disclosure can affect corporate image through customer concerns, analyst ratings, and financial performance. We explore the potential underlying mechanism from three aspects. First, carbon information disclosure improves the ratings of professional analysts. Second, carbon information disclosure improves customer image. Third, carbon information disclosure reduces the company’s costs and increases its income, thus improving its financial performance.

Signal theory helps to explain the behavior when two parties receive different and incomplete information [37]. Typically, one party—such as a company—chooses how to convey a message, and the other party—such as a consumer—chooses how to interpret a signal. Fundamentally, signal theory is about reducing information asymmetry between two parties. This two categories of information in which asymmetry is important: information about quality and information about intention. In the first case, information asymmetry is important when one party does not fully understand the achievements of the other. In the second case, information asymmetry is also important when one party is concerned about the actions or intentions of the other.

The previous research finds that corporate disclosure provides benefits by reducing information asymmetry between the firm and the outside world, and demonstrates that a better disclosure policy can reduce information asymmetry and increase investors’ information acquisitions. If companies disclose their carbon emissions, voluntary carbon disclosure behavior will give investors confidence by providing transparent nonfinancial information to customers about the measures they are taking to address the risk of climate change. Milgrom (1981) [38] finds that if an enterprise does not disclose its carbon emissions, then customers will not only wonder about its carbon emissions, but also may perceive the non-disclosure as a negative signal and punish the enterprise for the failure to disclose. In addition, companies are likely to continue to signal their carbon reduction achievements through traditional advertising in terms of the history of their products, people, and financial performance. The interconnected environment provides additional channels to validate and support brand quality and intentions. Burton et al. (2021) [39] think that customers can use social media platforms to search for useful, truthful, and reliable information about a company’s carbon reduction achievements in terms of products, people, and financial performance. Lee et al. (2022) [26] find that the use of social media has grown exponentially over the last decade and that these platforms allow customers to participate in the brand experience. This corporate-to-consumer interaction could increase consumer attention, which leads to a continuous improvement in brand quality, intention, and valuation. Consumers pay more attention to their peers and social media influencers as they disclose information about the carbon emissions produced by companies. All of this leads to a high level of customer attention and the incorporation of their behavior into the increasing value of the brand. We propose hypothesis two:

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

A firm’s brand value is associated with carbon information disclosure through customer attitude.

2.3.2. Carbon Information, Analyst Rating and Brand Value

In the accounting and finance literature, numerous articles provide evidence that investment analysts’ expectations of the future growth and performance of focal companies are good proxies for the expectations of the companies’ shareholders. More generally, these sell-side analysts are employed by brokerage and research firms to track the performance of specific companies over time. They generate and publish two main products: forecasts of future earnings and investments, and advise clients to buy, sell, or hold shares in these companies. These products used by market participants and document their significant impact on stock prices and trading volumes. From a sociological perspective, “analysts act as ‘surrogate investors’” because their recommendations and forecasts significantly affect investors’ interest in a company’s stock. Indeed, while analysts often disagree with a company’s prospects, certain currents of opinion, especially those from prominent analysts, could have a significant impact on prices. In the early 1990s, investment analysts began to witness the growing interest in companies implementing CSR programs, and began to explore publicly available CSR ratings and rankings provided by third parties. For example, the results of two earlier investor surveys on the broader area of corporate social responsibility and ethics: In the first case, 72% of US investors claimed to consider the ethics of a company when deciding whether to invest in its stock in 1993. Importantly, a second survey, conducted in 1994, found that 26% of investors said a company’s business practices and ethics were extremely important to their investment decisions.

Companies also view analyst ratings as a way to influence their brand value through independent third-party ratings. Independent analyst ratings show the improvement in the actual position and overall performance of the corporate company. These made managers give back to the community and change the way the corporates do business while pursuing financial performance targets. Cowan and Guzman (2020) [32,40] indicate that analyst rating is a highly observable diagnostic signal that can improve customer evaluations of brands because they are highly credible and signal good behavior. Yang et al. (2011) [35] found that financial analysts would improve the rating of CSR disclosure, and analysts would also improve the accuracy of the forecast after CSR disclosure. Thus, hypothesis 3 is proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

A firm’s brand value is associated with carbon information disclosure through analyst rating.

2.3.3. Carbon Information, Financial Performance and Brand Value

Brand reputation should be related to value, which means the company’s financial performance. According to the definition in the literature on management, this value correlation reflects investors’ expectations of the financial value from current, potential, internal, and external customer perspectives [41,42,43]. Roberts and Dowling (2002) [44] show that brand reputation is not only the asset of an enterprise, but also the driving factor behind its financial performance. It means that a brand is a financial asset from which the economic value gained by the business exceeds its potential to generate future cash flows. For Wang, Chen, Yu, and Hsiao (2015) [45], the economic dimension of ESG is positively and significantly correlated with the drivers of brand reputation. Baalbaki and Guzman (2016) [25,32] develop a consumer-perceived measure of brand equity based on quality, preference, social influence, and sustainability, and financial performance is one of the measures of sustainability. However, Cowan and Guzman (2020) [32] include annual domestic and international sales in the construction of brand value. Jiang Y et al. (2021) [46] find that firms with greater carbon disclosure have a higher firm value. Furthermore, the positive association between firm value and voluntary carbon disclosure is stronger in developing countries. They also find that large emitters with a sufficient carbon disclosure policy experience a less negative valuation than firms with inadequate carbon disclosure.

From the perspective of equity investors, carbon information disclosure will bring both costs and benefits. In general, carbon disclosure could lead companies to improve the efficiency of their carbon operations by reducing energy consumption, improving product quality, or recruiting staff in a better way, thus increasing revenue. In contrast, carbon information may also cause costs. The first includes the direct costs of preparing, disseminating, and issuing new information. However, this cost is fairly minimal for most companies. Alsaifi K et al. (2022) [47] show that enhanced voluntary carbon disclosure reduces a firm’s total, systematic, and idiosyncratic risks, and that this negative association is driven mainly by carbon-intensive industries. In addition, government regulators, such as the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency), could use disclosures as the basis for investigations into high-carbon-emitting companies and increase the compliance costs for those companies. Additionally, carbon disclosure could lead to costly lawsuits from previously unwitting victims of climate change linked to greenhouse gases, benefit competitors’ green marketing strategies aimed at environmentally conscious consumers, and provide ammunition for public interest groups [36]. In short, the market will penalize companies that voluntarily disclose their carbon emissions. Therefore, we propose hypothesis 4:

Hypothesis 4 (H4):

A firm’s brand value is associated with carbon information disclosure through corporate financial performance.

Figure 1 shows the influence mechanism of corporate carbon information disclosure on brand value.

Figure 1.

Conceptual source of brand value.

3. Research

3.1. Sample and Data

3.1.1. Carbon Information Disclosure Strategy

We use Python and develop code to collect carbon information disclosure data from annual reports and ESG reports in the following sequence: (1) Download all corporate annual reports and ESG reports from 2010 to 2020. (2) Construct a carbon keywords dictionary according to the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) questionnaire, “Global Framework on Climate Risk Disclosure” of CRDI (Climate Risk Disclosure Initiative) and the “Draft Climate Change Reporting Framework” of CDSB (Climate Disclosure Standards Committee). (3) Use Jieba to cut words from the corporate annual reports and ESG reports and then identify whether each word in each reports includes the carbon keywords constructed above. The carbon keywords dictionary we constructed refers to 13 aspects: (1) Opportunities and risks related to low-carbon development (e.g., “climate change risks” and “climate change opportunities”). (2) Carbon reduction quantitative targets (e.g., “low-carbon targets”). (3) Carbon reduction qualitative targets (e.g., “zero carbon”). (4) Carbon reduction strategy (e.g., “low-carbon strategy” and “carbon reduction plan”). (5) Carbon reduction institution and system (e.g., “carbon GSP” and “low-carbon system”). (6) Carbon trade (e.g., “CDM” and “carbon allowance”). (7) Low-carbon culture (e.g., “carbon neutrality concept” and “green carbon”). (8) Low-carbon research investment and achievement (e.g., “carbon recycling” and “carbon technology”). (9) Government recognition of carbon reduction (e.g., “low-carbon man of the year” and “low-carbon model corporate”). (10) Low-carbon resource input and recovery (e.g., “low-carbon industrial park”). (11) Carbon reduction performance (e.g., “saving standard coal”). (12) Carbon accounting standard (e.g., “GRI” and “CRID”). (13) Carbon accounting (e.g., “carbon emission”). These phrases are developed based on our reading of 100 randomly selected ESG reports, annual reports and official carbon disclosure documents mentioned above. The construction of this corporate company carbon information disclosure keywords dictionary is also one of our contributions. Then, to measure a firm’s carbon information disclosure level, we construct two indicators: the carbon score () and the carbon information disclosure strategy (). Carbon score () is the sum of the score of all the carbon information categories mentioned above. Its construction can be shown in Equation (1).

where is the score of every carbon information category mentioned above; this is every appearance of the keywords in every category, which is the value of plus one.

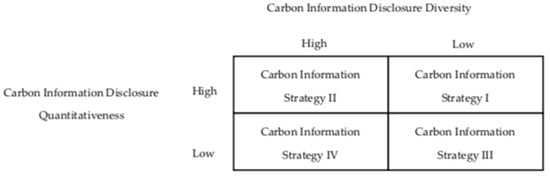

Furthermore, we classify the crate carbon information disclosure into four strategies. We describe carbon information into two dimensions: carbon information diversity and carbon information quantitativeness. Carbon information diversity indicates that the company discloses diverse categories, referring to more aspects of carbon information. A more complete framework would entail carbon information disclosure diversity and carbon information quantitativeness in the four carbon information strategies. Carbon Information Strategy I discloses high quantitative and low diverse carbon information. Carbon Information Strategy II discloses high quantitative and high diverse carbon information. Carbon Information Strategy III discloses low quantitative and low diverse carbon information. Carbon Information Strategy IV discloses high quantitative and low diverse carbon information. Figure 2 illustrates the classification of these four categories.

Figure 2.

Corporate Carbon Information Disclosure Strategy.

3.1.2. Corporate Brand Value

From the World Brand Lab, we obtain data on corporate company brand values from 2010–2020. The World Brand Lab is the most influential brand value estimation institution. It is a subsidiary of the magazine The Economist, which is dedicated to brand evaluation, brand communication, and brand management. Its experts and consultants come from Columbia University, the University of Cambridge, Tsinghua University, Harvard University, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, and other top universities around the world (the order of the list determines the instruction of The World Brand Lab). The World Brand Lab has also contributed a large amount of data and cases to the academic community. In the largest academic search engine (xueshu.baidu.com, accessed on 18 January 2023) in China, there are 54,800 results related to “World Brand Lab”. Among the three major academic citation databases in China, China Science and Technology Paper Citation Database has 2263 results; Peking University Paper Citation database has 1400 results; and China Science Citation Database has 714 results. In the world’s largest academic search engine (solar.google.com, accessed on 1 December 2022), the results for “World Brand Lab” total about 16,600.

Currently, the common brand evaluation methods include the Cost Price Method, Market Method, Income Calculation Method, and Economic Application Method. The World Brand Lab has adopted the adjusted Present Earning Value Method to evaluate brand values since 2019. We chose the Chinese Top 500 Brand Value List as the data source for the brand values of our sample companies. For example, the top Chinese brand value corporate in 2022 is the State Grid Corporation of China, and its value is 6015.16. Haier’s brand value is 4739.65, and it rates in the top 3.

3.1.3. Other Variables

We also use the corporate attention index as our control variable. The corporate attention index is manually collected and sorted through the Baidu search engine and the database of major Chinese newspapers (CCND). Then, it is divided into two categories: Baidu search volume index and the news media release index. The collection methods are as follows: (1) For each listed corporate, we collect and sort out the Baidu volume search index data based on the keywords stock code, company abbreviation, and company full name of Chinese listed companies. The Baidu search engine will automatically output the search index of each corporate, which we define as network media attention. (2) The news media release index comes from eight important newspapers, manually collected through the database of major Chinese newspapers (CCND), China Securities Journal, Securities Daily, Securities Times, Shanghai Securities News, China Business News, Economic Observer, 21st Century Business Herald, and China Business News. These two indexes could reflect the brand’s public attention from people and the media, and then influence corporate brand value.

The other firm-level financial data come from CSMAR (China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database), from which we select other controlling variables.

3.2. Model

To test H1 and H2, we examine whether carbon information disclosure has a positive impact on a firm’s reputation. In the empirical regression model, we control for other determinants of firm reputation to parse out potential confounding effects, such as the Baidu search volume index and news media release index. In addition, as brand value is part of corporate performance, we identify other firm-level factors that influence a firm’s brand value.

where is an indicator variable that equals the sum score of the 13 carbon keywords categories mentioned above. is the indicator variable that equals one if the firm, i, chooses a carbon information disclosure strategy, j, and equals zero otherwise. The regressions also include a number of firm-level control variables: is the news media release index that it used as the control variable and that reflects media attention on corporate companies; is the search volume index that is used as the control variable and that reflects the public’s attention. Other controlling variables are as follows: , , , , and . These variables control for firm characteristics, which could lead to variation in the observed market reactions (including several identified to affect other outcome variables).

4. Results

4.1. Summary Statistics

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and Table 3 presents the Pearson correlations for treatment observations (n = 1515). All variables are between 2010–2020 and are winsorized at the 1% and 99% levels. Table 1 reveals that the average brand value is 1270.625, and the carbon score is 12.403 (CS). The mean for carbon information disclosure strategy I is 0.058, for carbon information disclosure strategy II it is 0.307, for carbon information disclosure strategy III it is 0.450, and for carbon information disclosure strategy IV it is 0.183, and these scores range from 0 to 1. The mean analyst rating is 4.321 and this ranges from 1 to 5. The mean investor sentiment is 10.077, which reflects the low investor sentiment in the Chinese stock market. Table 2 reflects the correlations for observations. Carbon score is significantly positively correlated with brand value (0.362, p < 0.01). Carbon information disclosure strategy 2 is significantly positively correlated with brand value (0.302, p < 0.01), and Carbon information disclosure strategy 3 is significantly negatively correlated with brand value (−0.342, p < 0.01). These give preliminary evidence on the relationship between the carbon information disclosure strategy and the corporate brand value. In addition, the news media release index (NEWS) and search volume index (SEARCH) are both significantly positively correlated with brand value.

Table 2.

Description Statistics: Median, Standard deviation, Minimum, Maximum.

Table 3.

Correlations among Brand Value and other variables.

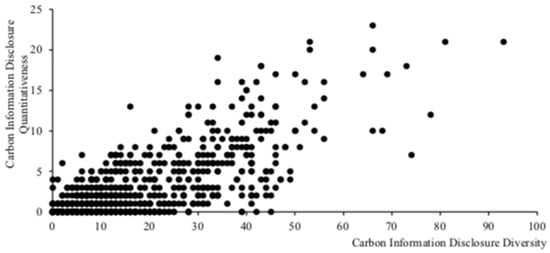

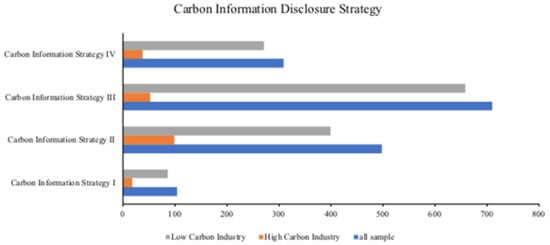

Figure 3 and Figure 4 provide an analysis of the extant corporate carbon information disclosure strategy. Figure 3 shows the two dimensions of corporate carbon information disclosure. We find that the carbon information disclosure level for the majority of firms is low and is concentrated on the low quantitative and low diverse carbon information disclosure level. Figure 4 shows the heterogeneity industry of corporate carbon information disclosure. It shows that most high-carbon industries choose to adopt carbon information disclosure strategy II, while low-carbon industries choose carbon information disclosure strategy III.

Figure 3.

The Diversity and Quantitativeness Dimensions of Corporate Carbon Information Disclosure.

Figure 4.

Heterogeneity Industry of Corporate Carbon Information Disclosure.

4.2. The Impact of Carbon Information Disclosure on Corporate Brand Value

Table 4 presents the primary results of the impact of the carbon information disclosure strategy on the corporate reputation of the sample (1515 firms). We also conduct two additional tests to assess the impact on the high-carbon industries and low-carbon industries in Table 5 and Table 6, which also provide robustness evidence. Table 4 shows that the coefficient of the carbon score for the full sample (coeff. = 0.088; p < 0.01) is positive and significant, consistent with H1. This result is also consistent with previous studies that also investigate the impact of carbon quality reports on corporate reputation, and the coefficient is 1.8106. This also demonstrates the positive impact of carbon information disclosure on corporate brand reputation. The coefficient of carbon disclosure strategy II for the full sample (coeff. = 0.066; p < 0.01) is positive and significant. This result means that a carbon information disclosure strategy that is of a high quantity and is highly transparent could increase brand value. The coefficient of carbon disclosure strategy III for the full sample (coeff. = −0.093; p < 0.01) is negative and significant. This means that a carbon information disclosure strategy that is of low quantity and of low transparency could decrease brand value.

Table 4.

The impact of the carbon information disclosure strategy on brand value.

Table 5.

Heterogeneity Industry analysis of the impact of the carbon information disclosure strategy on brand value.

Table 6.

Carbon Information Disclosure and Analyst Rating.

To examine whether the impact of carbon information disclosure on brand value differs for the high-carbon industries and low-carbon industries, we estimate Equation (3) separately for each group. Table 4 shows the impact of high-carbon industry and the coefficient is not significant. This means that the impact of the carbon disclosure strategy on brand value in the high-carbon industry is not significant. In contrast, Table 5 shows the impact of the low-carbon industry and the coefficient is significant, which is consistent with the result in Table 4. This result has economic significance because, for the low-carbon industry, the state does not have mandatory disclosure policies, so corporate companies disclose their carbon information voluntarily.

4.3. The Impact Mechanism of Carbon Information Disclosure on Corporate Reputation

The above results suggest that carbon information disclosure has a positive impact on corporate company brand value. Below, we provide evidence on the potential underlying mechanism through which voluntary carbon information disclosure increases brand value. We focus on three types of intermediaries: analyst rating, investor sentiment, and corporate financial performance.

4.3.1. Carbon Information Disclosure and Analyst Rating

First, we examine the effect of analyst forecast on the relationship between carbon information disclosure and brand value. Increased carbon information disclosure could increase levels of analyst coverage and lead to a reduction in the levels of forecast dispersion. These have the potential to increase corporate brand value. We run the following regressions following Lang and Lundholm (1996) [48].

where is the indicator variable from the analyst forecast report and has five categories. It equals 1 if the analyst forecast is sell, 2 when the analyst forecast is reduce, 3 when the analyst forecast is neutral, 4 when the analyst forecast is increase, and 5 when the analyst forecast is buy. is an indicator variable that equals the sum score of the 13 carbon keywords categories mentioned above. is the news media release index that is used as the control variable and that reflects media attention on corporate companies; is the search volume index that is used as the control variable that reflects the public’s attention. The regressions also include a number of firm-level control variables: , , , , and .

Table 6 presents the regression results for equation (3). Column (I) shows the results for the full sample, while Column (II) and Column (III) show the results for the high-carbon industry and low-carbon industry, respectively. Column (I) shows that there is a positive significant coefficient for (coeff. = −0.299, p < 0.05), which suggests that the brand value increases in terms of the analyst forecast with a higher carbon score performance. When the regression is run separately in the two groups of high-carbon industry and low-carbon industry, we find a significant positive coefficient (coeff. = 0.110, p < 0.01) for brand value, but only in the low-carbon industry.

4.3.2. Carbon Information Disclosure and Investor Sentiment

Second, we examine the effect of investor sentiment on the relationship between carbon information disclosure and brand value. Increased carbon information disclosure could influence investor sentiment and change the perception of the corporate company, which then has an impact on brand value. To determine whether carbon information disclosure influences investor sentiment and then corporate brand value, we follow Bushee and Noe (2000) [49] and estimate the below model:

where investor sentiment is the proxy variable that measures the corporate market turnover rate of the total circulating capital stock. is an indicator variable that equals the sum score of the 13 carbon keyword categories mentioned above. The regression also includes a series of control variables , , , , , , and

Table 7 displays the regression results. There is strong evidence that investor sentiment has a positive impact on the relationship between corporate company carbon information disclosure and brand value. The coefficient for is significant and positive (coeff. = 0.113, p = 5.640). To further examine this issue, we also run the regression in the two groups of high-carbon industry and low-carbon industry. The result shows that the impact of investor sentiment is significant in the low-carbon industry, but is only marginally significant in the low-carbon industry.

Table 7.

Carbon Information Disclosure and Investor Sentiment.

4.3.3. Carbon Information Disclosure and Corporate Performance

We additionally examine the effect of corporate performance on the relationship between carbon information disclosure and brand value. The corporate operating performance reflects profitability, which conveys a signal of strength to the outside world. This enables the company to build its image and increase its brand value. Thus, we investigate whether carbon information disclosure influences investor sentiment and has an impact on brand value, and to do so we follow the below regression:

where is an indicator variable that measures the total operating cost and is an indicator variable that measures the corporate’s total operating income. is the indicator variable that equals the sum score of the 13 carbon keyword categories mentioned above. The regression also includes a series controlling the variables: ,,, , , , and

Table 8 and Table 9 display the regression results of the impact of performance on the relationship between carbon information disclosure and brand value. There is weak evidence that corporate company performance affects carbon information disclosure and brand value. The coefficients of and are marginally significant. The result is consistent with Jiang et al. (2021) [46], who suggest that corporate company carbon information has a negative impact on company cost, which means that the carbon information brings additional cost. In addition, they also demonstrate the positive impact of carbon information on corporate revenue and Tobin’s Q, which is consistent with the results of our research. However, the significance (coeff. = 0.005, t = 0.534) of income (coeff. = 0.008, t = 1.133) is better than that of cost. This shows that the impact of income on the relationship is better than that of cost.

Table 8.

Carbon Information Disclosure and Corporate Cost.

Table 9.

Carbon Information Disclosure and Corporate Income.

5. Robustness

To address the problem of endogeneity, we next use a two-stage least squares (2SLS) approach, which uses instrumental variables to control for unobservable factors that may have an influence. In our research, we can only control for observable factors that are correlated with brand value. It is still possible that some unobservable variable may be driving the results (i.e., a correlated omitted variable). The two-stage least squares (2SLS) approach is advocated when the outcome of interest is dichotomous, such as in this setting. To implement this approach, we employ an instrumental variable, IFTRADE, which is an indicator variable that equals 1 when the corporate is located in a low-carbon city and 0 otherwise. The term low-carbon city refers to the «Notice on the Implementation of Low-Carbon Pilot Work in Provinces and Regions and Cities» issued by the National Development and Reform Commission on 10 August 2010, and comprises Guangdong, Liaoning, Hubei, Shanxi, Yunnan and Tianjin, Chongqing, Shenzhen, Xiamen, Hangzhou, Nanchang, Guiyang and Baoding. Corporate companies in these cities face more restrictive carbon information disclosure rules and thus disclose more carbon information.

Table 10 presents the result of the validity of the instrument. The instrument is positive and statistically significant in the first-stage model in the full sample, and has a partial R2 of 0.188 and a partial F-statistic that is highly significant (p-value, 0.000), confirming that the instrument is not weak [50]. Furthermore, the instrument appears to be appropriate, as the Hansen J-statistic from the over-identifying restrictions test fails to reject the null hypothesis that states that the instruments are uncorrelated with the error term in the second-stage model [51]. Thus, some confidence can be placed in the results of this 2SLS model. Table 10 shows the result of the second estimation. The coefficient of CS is positive and significant (coeff. = 2.158, p < 0.001). This is again consistent with H1, which predicts that carbon information disclosure is positively associated with corporate brand value. In terms of economic significance, the coefficient of carbon score suggests that firms that disclose carbon information have a positive impact on brand value, especially in the low-carbon industry (coeff. = 2.294, p < 0.01). These findings provide additional reassurance that the results are not driven by some unobservable correlated omitted variable. However, as with all instrumental variable models, these results should be interpreted with caution, because their reliability depends upon the validity of the instruments.

Table 10.

Two-Stage Least Squares Estimation.

6. Conclusions

This study uses the carbon emission information for 2010–2020 that was voluntarily disclosed in China’s ESG reports and annual reports. We find that corporate carbon information disclosure can improve corporate reputation, analyst forecasts and investor sentiment, and has a positive impact on the relationship between corporate carbon information and corporate reputation. Our study is the first to provide empirical evidence regarding the impact of the corporate carbon information strategy on corporate reputation and its potential mechanism.

We predict and find a positive relationship between carbon disclosure and brand value. Using the method of text mining to obtain the company carbon information disclosure strategy, we find that, for every 10-point increase in the carbon information disclosure score, brand value increased by 0.88 points on average. We found a positive relationship between the carbon information disclosure strategy and brand value, which raises the following question: “If the corporate carbon information disclosure strategy can affect company reputation, how does carbon information affect reputation?” We posit that, when an enterprise chooses to disclose more quantitative and diversified carbon information, it sends a positive signal that its management system is reasonable and that its carbon emission reduction measures are effective. These could have an impact on analysts’ forecasts for the company’s future, investor sentiment, and the company’s financial performance. Through a moderating analysis, we find that analyst forecasts and investor sentiment have a more significant impact on the relationship between corporate carbon information disclosure and brand value.

By providing academic evidence on the impact of the carbon information disclosure strategy on company reputation, we provide managers with information to help them make important decisions regarding the reputational effects of carbon disclosure. Our findings suggest that non-disclosure of carbon information could be costly and negatively impact a company’s reputation. The findings are also important for boards and managers because failing to incorporate climate change into business strategy could reduce company value.

7. Discussion

Our findings give policy recommendations for Chinese and international regulators and standard-setters when they work to develop standards for corporate carbon emissions reporting. Our results suggest that corporate reputation will incorporate information about the carbon information that firms choose to disclose. These estimates are in line with users’ demands that regulators and standard-setters develop clearer guidelines for measuring and disclosing carbon-related information. The Guidance on Social Responsibility of Listed Companies, issued by the Shenzhen Stock Exchange in 2006, encourages listed companies to proactively disclose corporate social responsibility reports and declare their pollutant emissions. The China Securities Regulatory Commission issued the Code of Governance for Listed Companies in 2018, which requires listed companies to disclose environmental information and other relevant information. In conclusion, China’s carbon disclosure is voluntary, and Chinese and international regulators and standard-setters have an important role to play in this regard and in considering whether to impose more uniform carbon disclosure policies in order to improve the reliability of the information.

Having found evidence of a positive association between carbon information disclosure and firm reputation, in future research, we plan to examine the association between carbon information and other components of the firm. Currently, international accounting research on the issuance of GHG emission statements is gaining momentum [52], thus pointing to the increasing relevance of this issue. In addition, increasing studies are focusing on sustainability management [52,53]. As more years of data become available from private and publicly available sources, future research could examine the association between carbon information and market value and other components.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M., X.L. and S.L.; Methodology, Y.L.; Writing—original draft, B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number Project No. 71850014, 71974180.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data used and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author by request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ameli, N.; Kothari, S.; Grubb, M. Misplaced expectations from climate disclosure initiatives. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2021, 11, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, E.M.; Prakash, R.; Vera-Muñoz, S.C. Firm-Value Effects of Carbon Emissions and Carbon Disclosures. Account. Rev. 2014, 89, 695–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadir, S.C.; Bharadwaj, S.G.; Srivastava, R.K. Financial Value of Brands in Mergers and Acquisitions: Is Value in the Eye of the Beholder? J. Mark. 2008, 72, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujica, A.; Villanueva, E.; Lodeiros-Zubiria, M. Micro-learning Platforms Brand Awareness Using Social media Marketing and Customer Brand Engagement. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2021, 16, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, I.; Khanna, M.; Rai, K.A. Attribution analysis of luxury brands: An investigation into consumer-brand congruence through conspicuous consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, N.; Antil, A.; Gunasekaran, A.; Malik, K.; Balakumar, S. Environment-social-governance disclosures nexus between financial performance: A sustainable value chain approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 186, 106571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, L.; Buoye, A.J.; Fors, M.; Keiningham, T.L.; Rosengren, S. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) metrics do not serve services customers: A missing link between sustainability metrics and customer perceptions of social innovation. J. Serv. Manag. 2022, 33, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.; Sen, S. Reaping Relational Rewards from Corporate Social Responsibility: The Role of Competitive Positioning. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2007, 24, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimo, N.; Caragnano, A.; Zito, M.; Vitolla, F.; Mariani, M. Extending the benefits of ESG disclosure: The effect on the cost of debt financing. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, V.; Sorescu, A.; Steenkamp, J.-B.E.M.; O’Guinn, T.C.G.; Schmitt, B. Branding in a Hyperconnected World: Refocusing Theories and Rethinking Boundaries. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinberg, M.; Ozkaya, H.E.; Taube, M. Do Corporate Image and Reputation Drive Brand Equity in India and China?-Similarities and Differences. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Calder, B.J. The experimental evaluation of brand strength and brand value. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 115, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Sorescu, A. Wedded Bliss or Tainted Love? Stock Market Reactions to the Introduction of Cobranded Products. Mark. Sci. 2013, 32, 939–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutordoir, M.; Verbeeten, F.H.M.; De Beijer, D. Stock Price Reactions to Brand Value Announcements: Magnitude and Moderators. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2015, 32, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agus Harjoto, M.; Salas, J. Strategic and Institutional Sustainability: Corporate Social Responsibility, Brand Value, and Interbrand Listing. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2017, 26, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.; Fournier, S.; Srinivasan, S. Brand Architecture Strategy and Firm Value: How Leveraging, Separating, and Distancing the Corporate Brand Affects Risk and Returns. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 44, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, A.M.; O’Guinn, T.C. Brand Community. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 27, 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epp, A.M.; Schau, H.J.; Price, L.L. The Role of Brands and Mediating Technologies in Assembling Long-Distance Family Practices. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, T.; Haiying, D. How to achieve consumer continuance intention toward branded apps—From the consumer–brand engagement perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L.; Lehmann, D.R. Brands and Branding: Research Findings and Future Priorities. Mark. Sci. 2006, 25, 740–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B. The Consumer Psychology of Brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2011, 22, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Huang, J.; Yu, S.X. Buy domestic or foreign brands? The moderating roles of decision focus and product quality. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022, 34, 843–861. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.A. The value of brand equity. J. Bus. Strategy 1992, 13, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, F. A brand building literature review. ICFAI J. Brand. Manag. 2005, 2, 30–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.T.; Raschke, R.L.; Krishen, A.S. Signaling Green! Firm Esg Signals in an Interconnected Environment That Promote Brand Valuation. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 138, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Mansilla, Ó.; Berenguer-Contrí, G.; Serra-Cantallops, A. The impact of value co-creation on hotel brand equity and customer satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, C.; Grace, D.; Iacono, J.L.; Carlini, J. Exploring the interplay between customer perceived brand value and customer brand co-creation behaviour dimensions. J. Brand Manag. 2020, 27, 466–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, S.; Dumay, J. Corporate ESG reporting quantity, quality and performance: Where to now for environmental policy and practice? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1091–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, S. Millennials driving brands to practice socially responsible marketing. Forbes 2017, 15, 58–75. [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo, C.; Abratt, R. Brands That Do Good: Insight into Social Brand Equity. J. Brand Manag. 2017, 25, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, K.; Guzman, F. How Csr Reputation, Sustainability Signals, and Country-of-Origin Sustainability Reputation Contribute to Corporate Brand Performance: An Exploratory Study. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinberg, M.; Katsikeas, C.S.; Ozkaya, H.E.; Taube, M. How nostalgic brand positioning shapes brand equity: Differences between emerging and developed markets. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 869–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, V.; Iglesias, O.; Markovic, S.; Singh, J.J. Does Ethical Image Build Equity in Corporate Services Brands? The Influence of Customer Perceived Ethicality on Affect, Perceived Quality, and Equity. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 144, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.G.; Tsang, A.; Li, O.Z.; Dhaliwal, D.S. Voluntary Nonfinancial Disclosure and the Cost of Equity Capital: The Initiation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting. Account. Rev. 2011, 86, 59–100. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, T.; Galan, J.I. Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Brand Value. J. Brand Manag. 2011, 18, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling Theory: A Review and Assessment. J. Manag. 2010, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, P.R. Good News and Bad News: Representation Theorems and Applications. Bell J. Econ. 1981, 12, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, J.L.; Mosteller, J.R.; Hale, K.E. Using Linguistics to Inform Influencer Marketing in Services. J. Serv. Mark. 2020, 35, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baalbaki, S.; Guzmán, F. A Consumer-Perceived Consumer-Based Brand Equity Scale. J. Brand Manag. 2016, 23, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, F.; Davis, D. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Brand Equity: Consumer Responses to Two Types of Fit. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2017, 26, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Serafeim, G.; Krzus, M.P. Market Interest in Nonfinancial Information. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2011, 23, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, S. Brand Equity as a Signaling Phenomenon. J. Consum. Psychol. 1998, 72, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.W.; Dowling, G.R. Corporate Reputation and Sustained Superior Financial Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.H.-M.; Chen, P.-H.; Yu, T.H.-K.; Hsiao, C.-Y. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Brand Equity and Firm Performance. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2232–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Luo, L.; Xu, J.; Shao, X. The value relevance of corporate voluntary carbon disclosure: Evidence from the United States and BRIC countries. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2021, 17, 100279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaifi, K.; Elnahass, M.; Al-Awadhi, A.M.; Salama, A. Carbon disclosure and firm risk: Evidence from the UK corporate responses to climate change. Euras. Bus. Rev. 2022, 12, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Lundholm, R. The relation between security returns, firm earnings, and industry earnings. Contem. Account. Res. 1996, 13, 607–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushee, B.; Noe, C.; Berger, P.G. Corporate disclosure practices, institutional investors, and stock return volatility. J. Account. Res. 2000, 38, 171–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcker, D.F.; Rusticus, T.O. Endogeneity and Empirical Accounting Research. Eur. Account. Rev. 2007, 16, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simnett, R.; Green, W.; Huggins, A. The Competitive Market for Assurance Engagements on Greenhouse Gas Statements: Is There a Role for Assurers from the Accounting Profession? Curr. Issues Audit. 2011, 5, A1–A12. [Google Scholar]

- Pop, R.-A.; Dabija, D.-C.; Pelău, C.; Dinu, V. Usage Intentions, Attitudes, and Behaviors towards Energy-Efficient Applications during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2022, 23, 668–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lăzăroiu, G.; Valaskova, K.; Nica, E.; Durana, P.; Kral, P.; Bartoš, P.; Maroušková, A. Techno-Economic Assessment: Food Emulsion Waste Management. Energies 2020, 13, 4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).