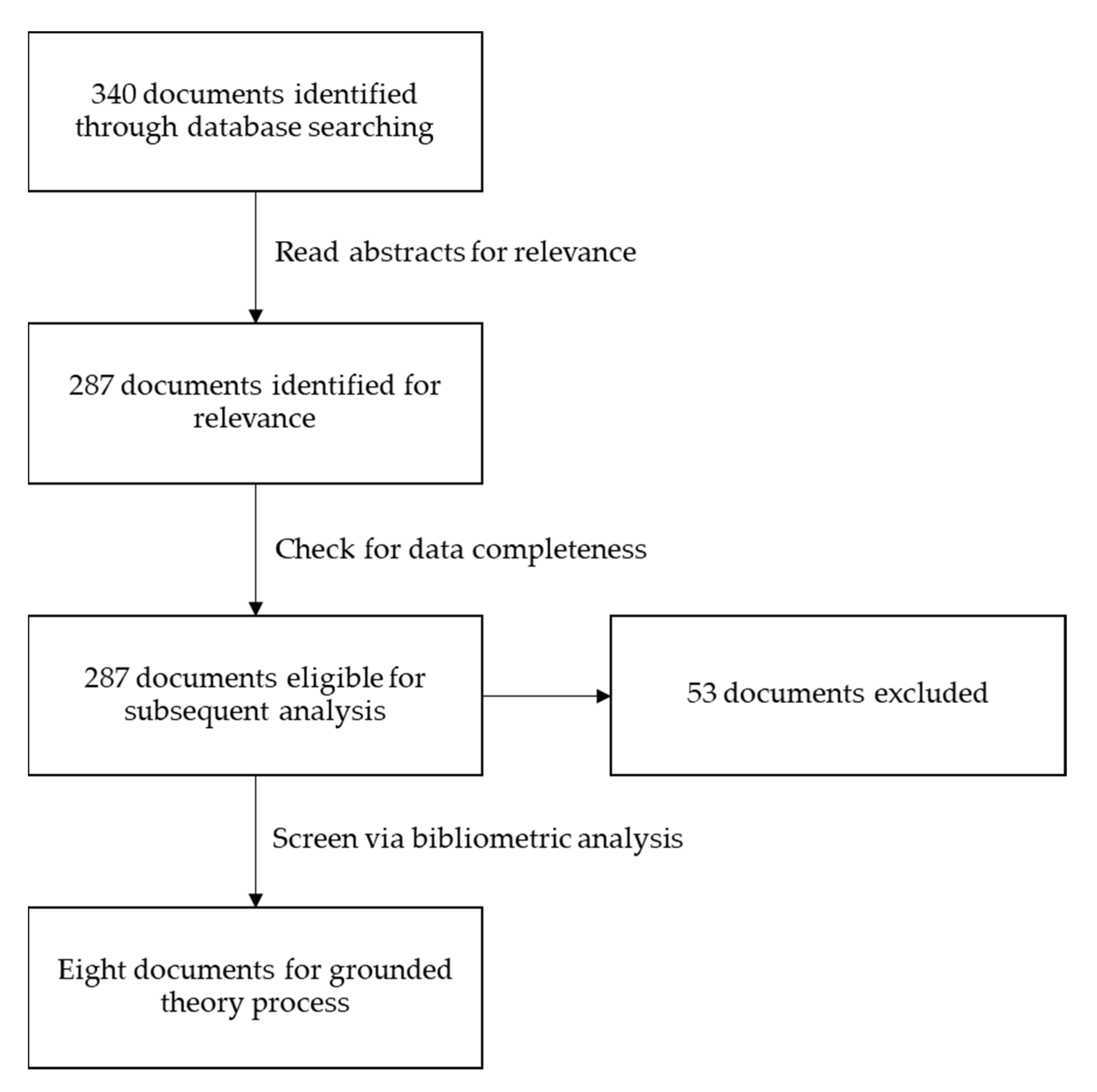

To address RQ #1, a series of analyses of citations and co-citations are conducted, with author and document serving as the two units of analysis, as described in greater detail below.

4.1.1. Author Citation and Co-Citation Analyses

The bibliometric evaluation can be employed to identify important authors and documents for knowledge generation [

49]. To identify scholars, schools of thought, and diverse levels of impact, as well as to rank these scholars according to the quantity of pertinent publications and citations, we use the bibliometric analysis (

Table 2).

The top five most cited and the first eighteen scholars in the brand and sustainability literature by total Scopus citations are shown in

Table 1. Among them, the top four most productive scholars in this area are Powell, S.M. (4), Gupta, Suraksha (3), Kumar, V. (2), and Lin, J. (2).

The author co-citation analysis (ACA), which visualizes the intellectual structure used by the authors, is used to assess important writers in the literature on brand and sustainability. When two writers are cited jointly in a different publication, this analysis counts as one. According to Bayer et al. [

50], this co-citation frequency reveals a degree of effect on the knowledge area both directly and indirectly. Based on the results of an author co-citation analysis presented in

Table 3, the top 10 foundation authors in the literature on brands and sustainability are as follows:

Interestingly, none of the top ten foundation scholars appear on the list of top-cited authors, indicating that the foundation knowledge in the brand and sustainability literature is not specifically related to sustainability brand. It is not a surprise that Keller is the top co-cited scholar in this area since he is well known as a pioneering scholar in the brand management field. Thus, it makes much sense that a well-known brand management scholar contributes his knowledge to the foundation knowledge of the sustainability and brand literature. However, we need to note that Keller’s work focuses almost solely on brand as perceived by customers (known as customer-based brand equity), as opposed to a broad range of stakeholders. This note is also true for all other brand scholars in this author co-citation ranking, such as Sen, Bhattacharya, and Aaker. In addition to the brand management scholars, Fornell and Hair have also contributed to the broad areas of quantitative customer satisfaction measurement and quantitative research methods in general. We can draw from the author co-citation analysis at this point that the specific body of knowledge on sustainability brand is not well established in the literature yet. Scholars have focused their efforts on brand as perceived by customers and still rely to a large extent on the literature from other relevant knowledge bases to inform the development of their studies.

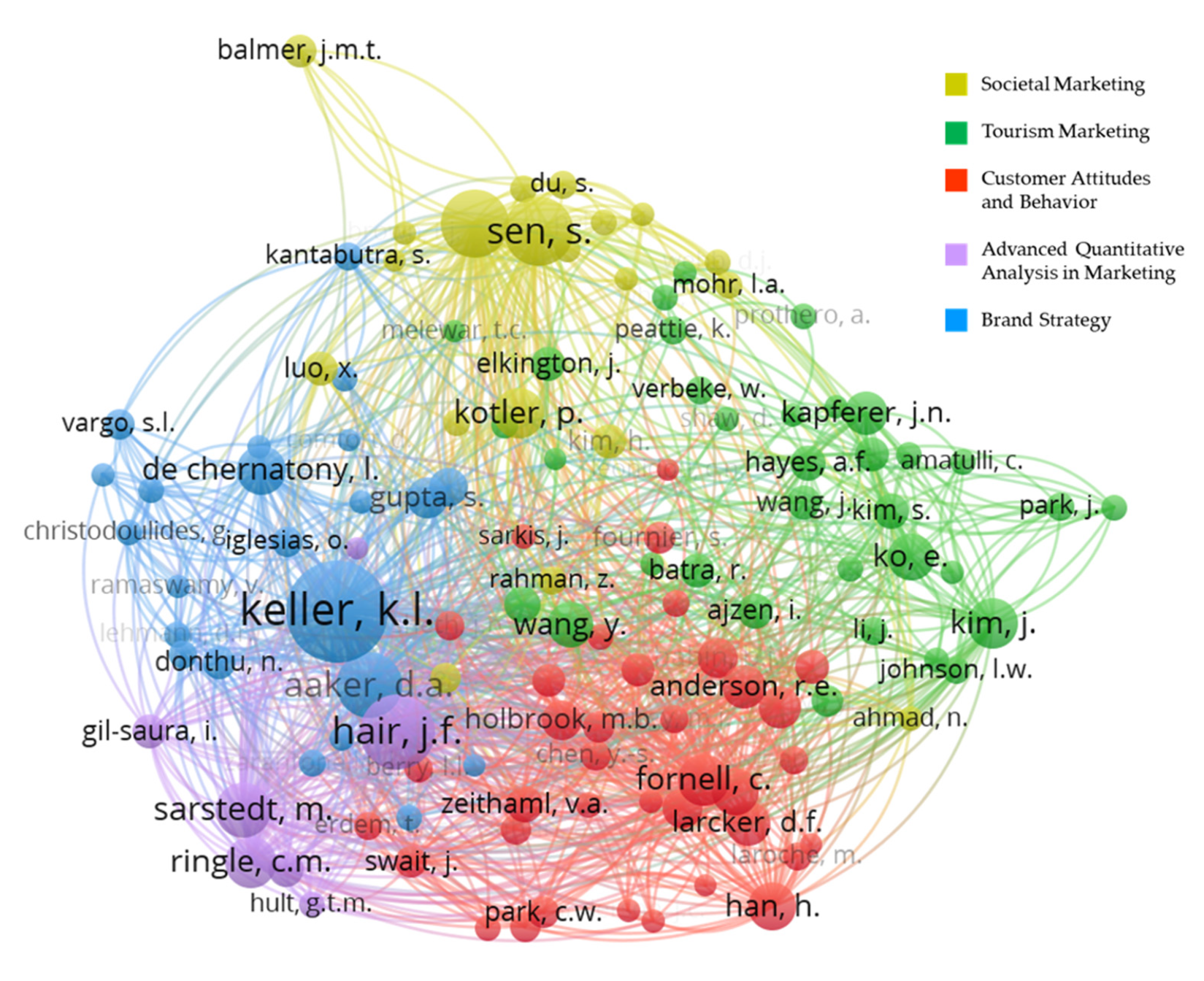

With regard to an examination of the various schools of thought that may be discovered in the brand and sustainability literature, the author co-citation map presents five key clusters, often known as “school of thought”, which collectively and cohesively depict the intellectual structure of the brand and sustainability knowledge base (

Figure 2), which is the response to RQ #3.

Following are five major schools of thought on the brand and sustainability literature: Brand Strategy (the blue cluster), Advanced Quantitative Analysis in Marketing (the purple cluster), Customer Attitudes and Behavior (the red cluster), Societal Marketing (the yellow cluster), and Tourism Marketing (the green cluster). Each school of thought provides a different perspective on brand and sustainability. The top-three scholars for each school are shown in

Table 4 below.

The first red school of thought, led by Fornell, Han, and Bagozzi, has the most members (37 total) and is the largest. Surprisingly, only Han is found in our Scopus data set as the 11th top-cited scholar, highlighting the value of co-citation analysis, which makes it possible to include cited documents from sources other than Scopus in the analysis. Fornell is well known for his American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI), a type of market-based performance measure for firms, industries, economic sectors, and national economies [

51]. The index employs the econometric approach to estimate the indices, a reason Fornell is often perceived as a scholar in the quantitative research methods knowledge base. Similarly, Bagozzi has contributed to two streams of research. The first one is basic research into human emotions, decision making, social identity, ethics, theory of mind, theory of action, and neuroscience (e.g., [

52]), while the other is research into multivariate statistics and its relationship to measurement, construct validity, theory, hypotheses testing, and the philosophy of science (e.g., [

53]). Like Fornell, Bagozzi is often perceived as a scholar in the quantitative research methods knowledge base. We determine that Fornell and Bagozzi contribute their knowledge to this cluster on customer attitudes and behavior because the cluster to which they belong is clearly distinct from the other cluster (in purple) that focuses on advanced quantitative analysis. In addition, Han, as the second most co-cited scholar in this school, confirms our conclusion, since he has focused his research on consumer behavior, particularly in the tourism industry. Therefore, it is reasonable to name this school of thought “Customer Attitudes and Behavior”.

As the second largest cluster, with 34 scholars, the green cluster is led by Kim, Ko, and Wang. As the leading scholar in this cluster, Kim, as the eighth top co-cited scholar, has contributed to the area of traveler satisfaction and experience. Similarly, Wang has focused his research efforts on hospitality, destination marketing, and branding. In addition, Ko has focused her research efforts on marketing communication and fashion brand management. Fashion has a strong linkage with specific tourism segments such as creative tourism, shopping tourism, and cultural tourism, as it associates with luxury and culture experiences, events, and leisure. Therefore, we name this school of thought “Tourism Marketing”.

Led by Keller, Aaker, and de Chernatony, the third largest cluster in blue has 23 scholars. Given that this cluster is exclusively about brand strategy, it is a surprise that none of the three leading scholars are among the top-cited scholars in the brand and sustainability data set. However, Keller, Aaker, and de Chernatony are ranked at 1st, 5th, and 10th in our author co-citation ranking. As the top co-cited scholars, Aaker and Keller have contributed to the area of branding and they are globally known for the brand equity model. While brand equity has later been widely considered a measure for corporate sustainability (e.g., [

21,

22,

54]), the core focus of brand strategy and brand equity are to create competitive point-of-differences and maintain long-term brand values, consistent with long-term orientation of the sustainability concept. One of Keller’s studies also found that corporate societal marketing can build brand equity [

55]. de Chernatony has also focused his research efforts on brand building. Thus, we name this school of thought “Brand Strategy”.

The fourth largest school of thought in the yellow cluster comprises 20 scholars, led by Bhattacharya, Sen, and Kotler. Surprisingly, none of them are listed among the top-cited scholars in our brand and sustainability data set. As the fourth and third scholars in the list of top co-cited scholars, Bhattacharya and Sen have focused their research efforts on corporate social responsibility and corporate reputation. They have contributed to the area of the intersection of sustainability and consumer behavior, i.e., when, how, and why consumers and employees respond to companies’ sustainability/corporate social responsibility endeavors. As the ninth top co-cited scholar, Kotler is a globally recognized marketing scholar [

56] who introduced the strategic marketing for sustainable competitive advantages under the concern about finite resources and the rising of environmental and social costs. In the brand and sustainability literature, Kotler has made contributions to social marketing, demarketing, and brand activism, with the idea that businesses must go beyond corporate social responsibility to address the world’s most pressing issues. These sustainability trends in marketing have been implemented across the broad contexts such as business-to-consumers, business-to-business, products, services, and hospitality industries. Thus, we name this school of thought “Societal Marketing”.

Finally, the smallest school of thought in the purple cluster comprises seven scholars, led by Hair, Sarstedt, and Ringle. Similarly, none of them appear in the list of top-cited scholars in our dataset. However, Hair, Sarstedt, and Ringle are ranked second, sixth, and seventh, respectively, on our list of top co-cited scholars. All three scholars have contributed to the area of quantitative modeling, particularly structural equation modelling. We can draw from this finding that the literature on brand and sustainability is predominantly quantitative. Therefore, we name this school of thought “Advanced Quantitative Analysis in Marketing”.

The proximity of the two schools—Brand Strategy and Advanced Quantitative Analysis in Marketing—shows how closely their respective fields of knowledge are intertwined. On the other hand, there is a large distance between the Tourism Marketing and Societal Marketing schools of thought and the Brand Strategy school of thought, indicating that research conducted by the first two schools is not very much related to brand strategy. Additionally, research in the Brand Strategy school is more closely related to the Customer Attitudes and Behavior school of thought than the two schools of Tourism Marketing and Societal Marketing, which makes much sense since brand is traditionally considered as a perception from customers. Therefore, it can be concluded from the distances among the clusters that the brand and sustainability literature is dominated by quantitative marketing methods and influenced by the literature on customer attitudes and behaviors.

4.1.2. Document Citation and Co-Citation Analyses

The top brand and sustainability articles (

Table 5) provide information about the organizational locus of these pieces, which helps to address RQ #2.

The analysis of document citations endorses the existence of three distinct schools of thought: Tourism Marketing, Brand Strategy, and Societal Marketing. Of the top-ten cited documents, three are from the Tourism Marketing school, two from the Societal Marketing school, and one from the Brand Strategy school. The rest do not belong to any of the schools of thought. In terms of quality, out of ten, nine were published by Q1 journal and one by a Q2 journal, suggesting that they are of very high quality.

Then, to investigate papers that have been regularly co-cited, we use document co-citation analysis (

Table 6). Publications from our brand and sustainability data set, as well as noteworthy and influential documents not included in the dataset, are included in the final documents.

All the first eleven top documents by co-citations were published with Q1 journals, four of which are from the

Journal of Marketing, reflecting the high quality of the foundation literature in the brand and sustainability domain. Five of the documents belong to the Customer Attitudes and Behavior school of thought, four from the Brand Strategy school of thought, and one from the Societal Marketing school of thought, suggesting that the foundation literature in the domain of brand and sustainability is dominated by the literature on customer attitudes and behavior and strategic brand management, which makes much sense since brand is traditionally considered as a perception from consumers. In the sustainability literature, brand equity is considered as a perception from a wide range of stakeholders [

21]. That is possibly the reason one document is from the Societal Marketing school of thought. Notably, there is no document commonly identified by both citation and co-citation analyses.

4.1.3. Co-Occurrence Analysis

In order to provide support for the earlier citation studies and to provide an answer to RQ #4, we use the co-occurrence analysis method. According to Zupic and Cater [

47], this is accomplished by adding subject specializations to the brand and sustainability studies. The author keyword co-occurrence search is configured with a threshold of five keyword occurrences. The selection of author keywords is justified by the fact that, given the study topic, authors are best positioned to say whether their works are connected to brand and sustainability.

A total of 28 out of the 1129 keywords satisfy the requirement (see

Table 7).

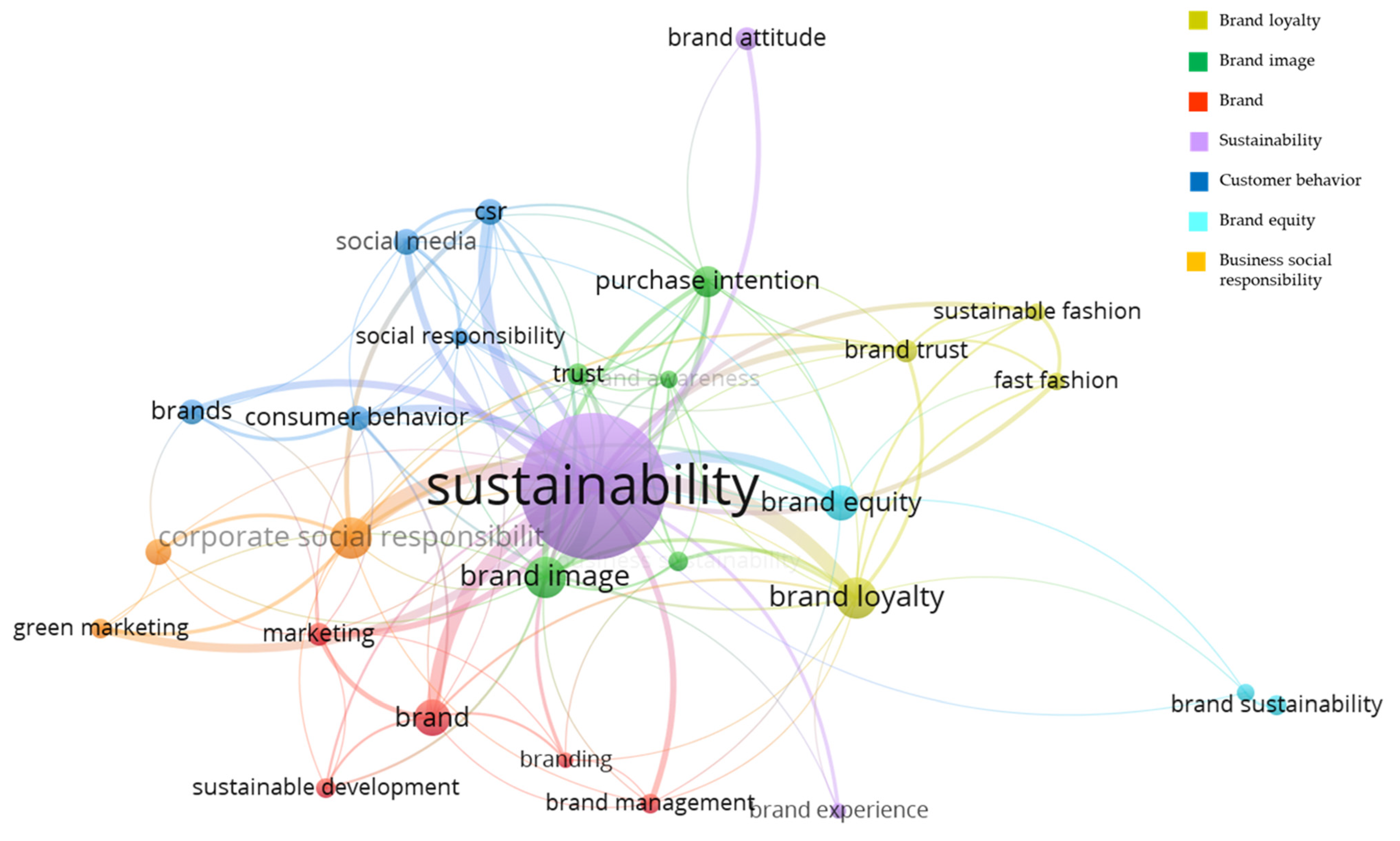

Figure 2 shows a co-word map that demonstrates the relative weighting of various different words connected to brand and sustainability. A connecting line that represents a link strength has a thickness between keyword nodes that denotes the existence of a relationship between those nodes.

The first ten frequently appearing keywords in the review dataset show that these terms are pertinent and of interest to brand and sustainability scholars, as shown in

Table 7. Sustainability, along with words containing the word “brand”, is the word that appears the most frequently in the literature and has the strongest link to it.

Therefore, according to major node sizes, the document co-occurrence science map (

Figure 3) shows seven clusters of topical focuses. The topical focus for the red cluster is “brand”, whereas the topical focus for the green cluster is “brand image”. While brand loyalty is the topical focus of the yellow cluster, “customer behavior” is the topical focus of the dark blue cluster. While brand equity is the topical focus for the light blue cluster, “sustainability” is the topical focus for the purple cluster. The orange cluster also identifies the topical focus as “business social responsibility”.

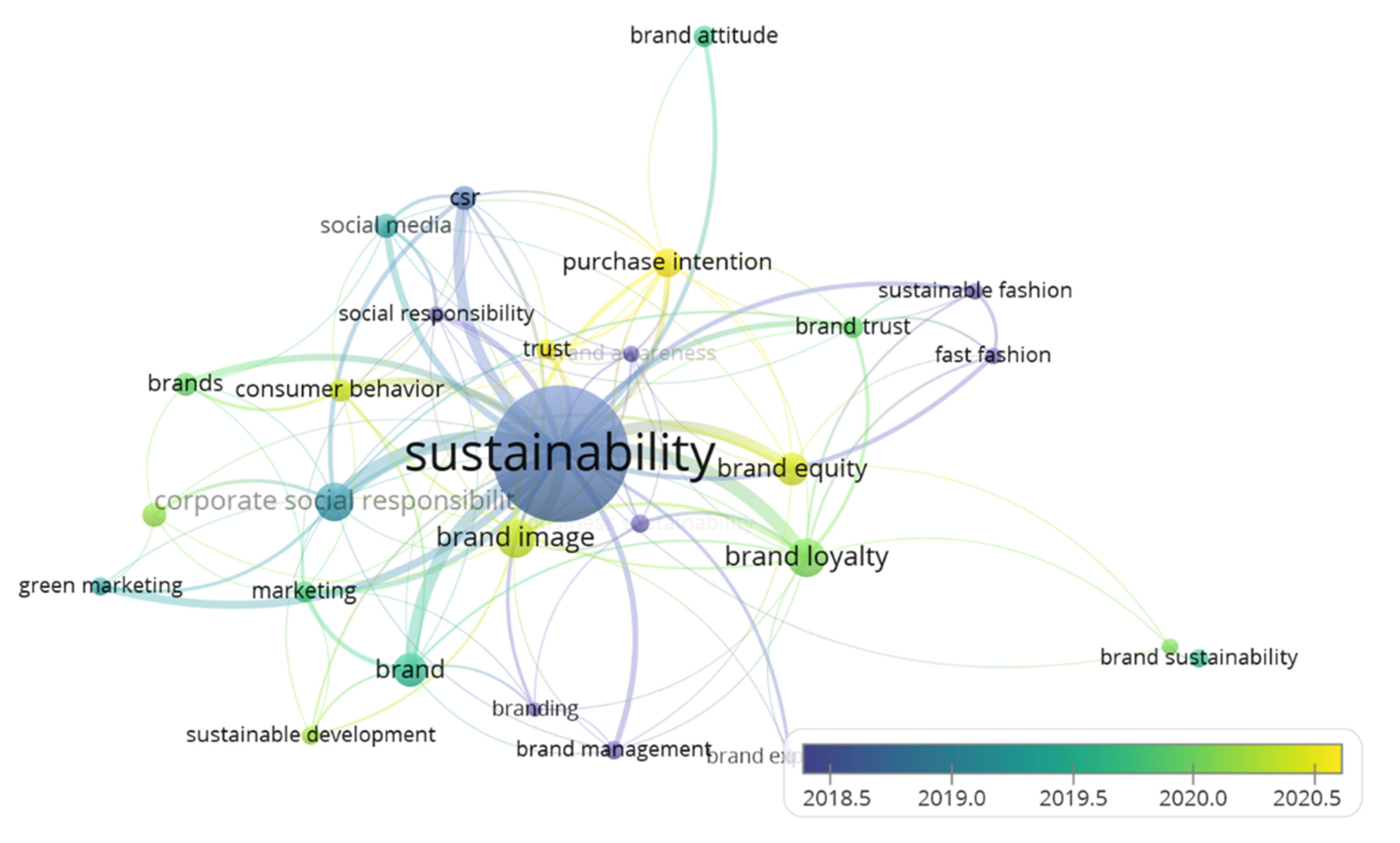

Because the literature is always evolving, especially following the introduction of new knowledge, scholars are quick to respond to shifts in the environment. According to Boyack and Klavans [

46] and Zupic and Cater [

47], the “research front” of the knowledge base literature can be determined using scientific mapping. We depict science mapping in this work to explain the research frontiers and the most interesting topics among scholars (See

Figure 4). Given that the average year these keywords were published is earlier than 2018, the overlay virtualization map (

Figure 4) suggests that the majority of them are very recent. Sustainability, branding, brand management, and brand experience are some of them. Between late 2018 and early 2019, more fresh research on CSR and green marketing was conducted. Mid-2019 to early-2020 marks the beginning of brand, brand loyalty, and brand image study. Most recently, research on brand equity and buying intention has started as of mid-2020.