Job Crafting, Job Boredom and Generational Diversity: Are Millennials Different from Gen Xs?

Abstract

1. Introduction

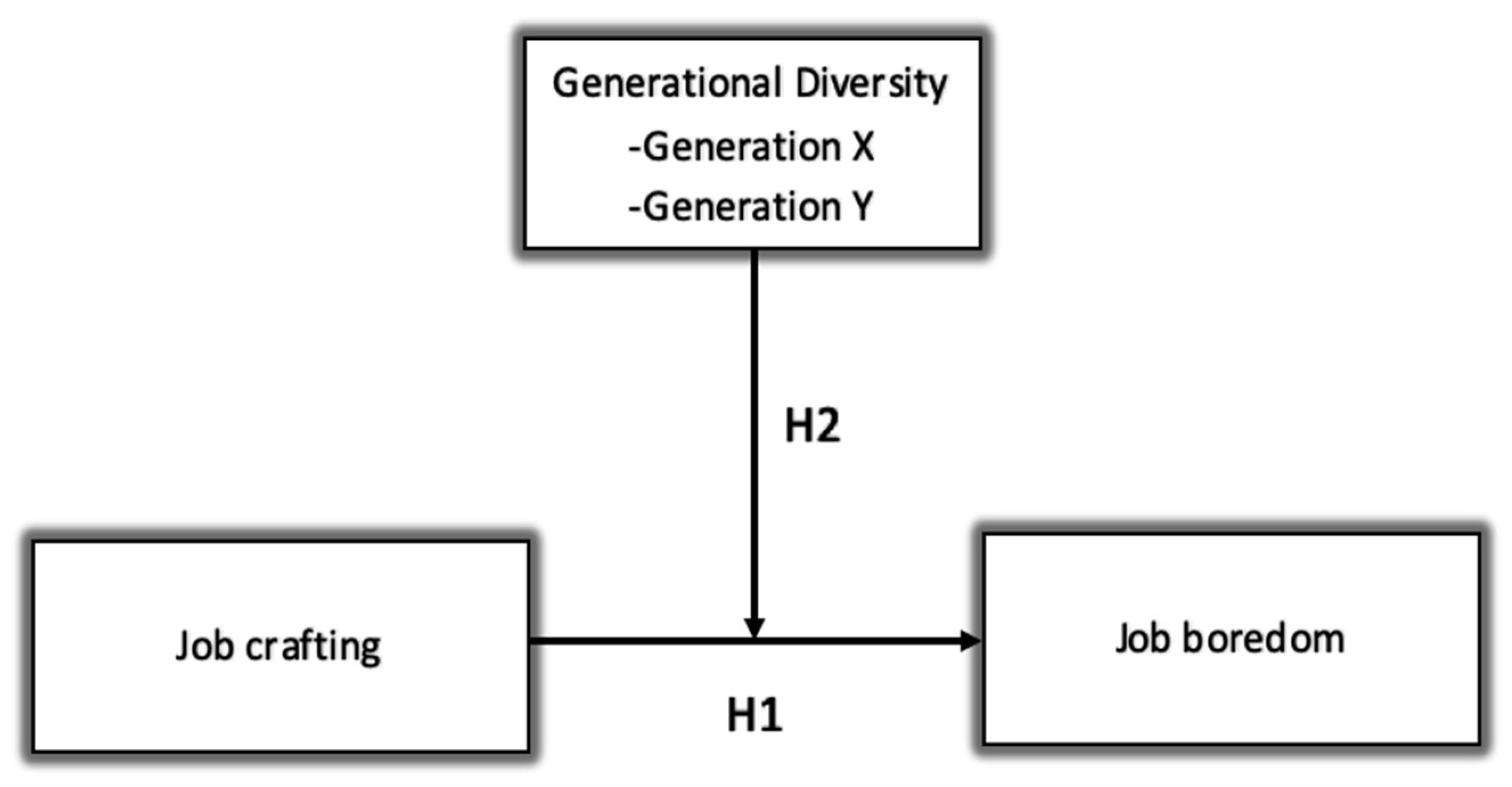

2. Theory and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Job Crafting

2.2. Job Crafting and Job Boredom

2.3. Moderating Role of Generational Diversity

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Control Variables

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

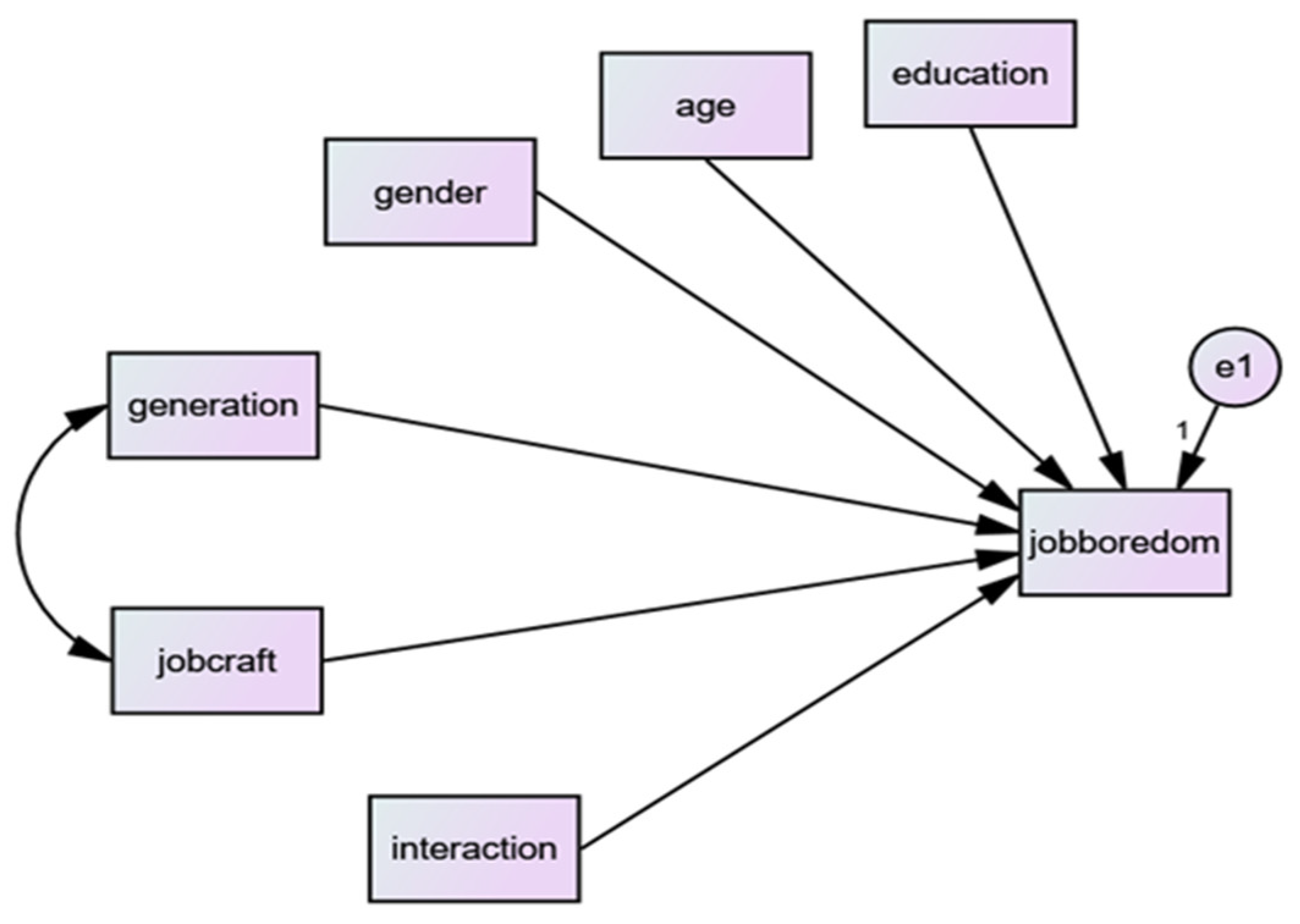

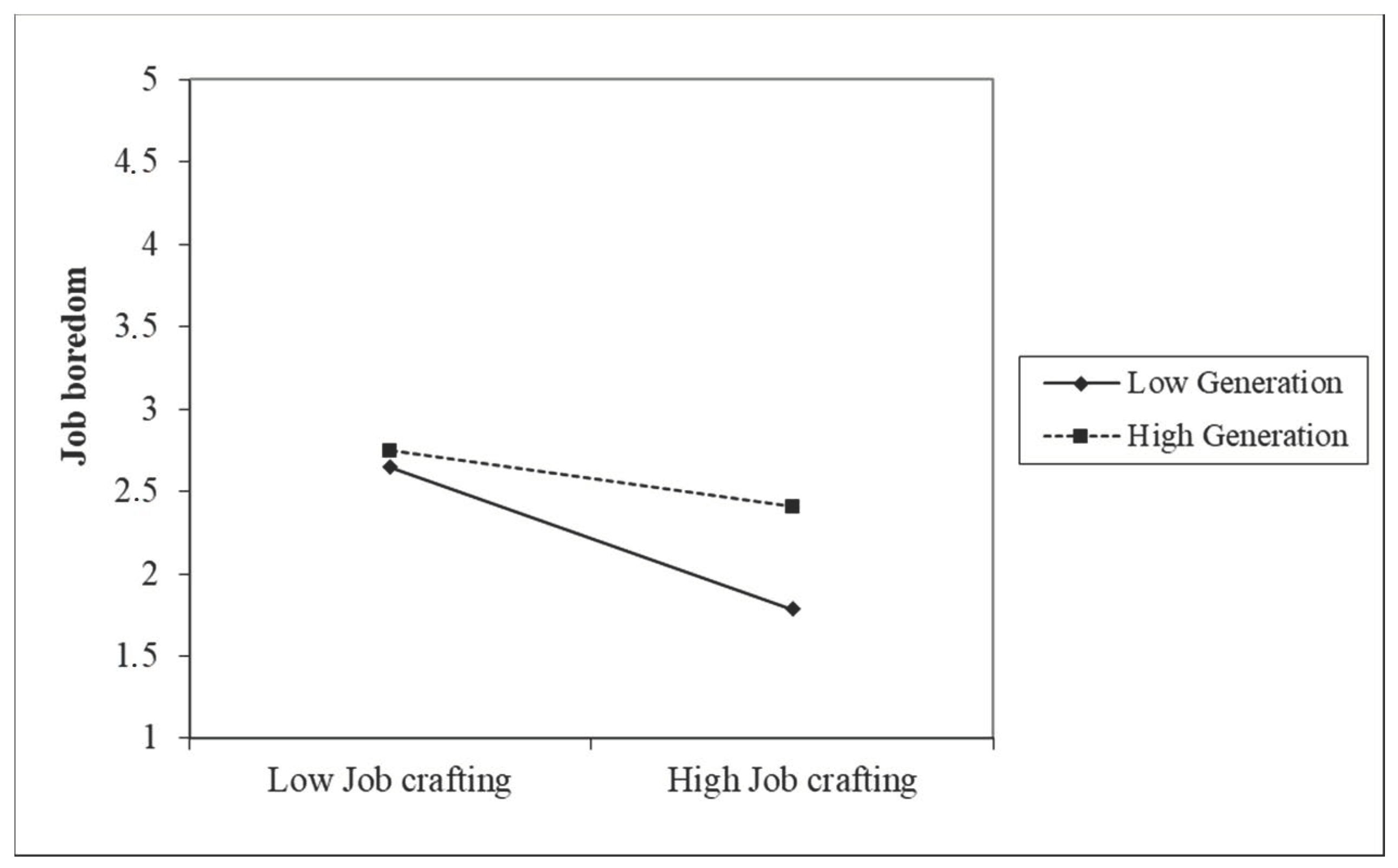

4.2. Test of Hypothesis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Limitations, Future Research and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a Job: Revisioning Employees as Active Crafters of Their Work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, H.J.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P.M.; Bakker, A.B.; Bipp, T.; Verhagen, M.A.M.T. Individual Job Redesign: Job Crafting Interventions in Healthcare. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 104, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, D.T.; van Woerkom, M.; Wilkenloh, J.; Dorenbosch, L.; Denissen, J.J. Job Crafting towards Strengths and Interests: The Effects of a Job Crafting Intervention on Person–Job Fit and the Role of Age. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Katz, I.M.; Lavigne, K.N.; Zacher, H. Job Crafting: A Meta-Analysis of Relationships with Individual Differences, Job Characteristics, and Work Outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 102, 112–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Peeters, M.C. The Job Crafting Intervention: Effects on Job Resources, Self-Efficacy, and Affective Well-Being. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 88, 511–532. [Google Scholar]

- Mattarelli, E.; Tagliaventi, M.R. How Offshore Professionals’ Job Dissatisfaction Can Promote Further Offshoring: Organizational Outcomes of Job Crafting. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 52, 585–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Jex, S. Workplace Boredom: An Integrative Model of Traditional and Contemporary Approaches. Group Organ. Manag. 2015, 40, 131–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P. Integrating Mediators and Moderators in Research Design. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2011, 21, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, E.; Wong, S.I. Crafting One’s Job to Take Charge of Role Overload: When Proactivity Requires Adaptivity across Levels. Lead. Q. 2016, 27, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenninkmeijer, V.; Hekkert-Koning, M. To Craft or Not to Craft. Career Dev. Int. 2015, 20, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Axtell, C.M.; Turner, N. Designing a Safer Workplace: Importance of Job Autonomy, Communication Quality, and Supportive Supervisors. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, C.; Solomon, N. Understanding and Managing Generational Differences in the Workplace. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. 2011, 3, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeberle, K.; Herzberg, J.; Hobbs, T. Leading the multigenerational work force. A Proactive approach will cultivate employee engagement and productivity. Healthc. Exec. 2009, 24, 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Becton, J.B.; Walker, H.J.; Jones-Farmer, A. Generational Differences in Workplace Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 44, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lub, X.; Nije Bijvank, M.; Matthijs Bal, P.; Blomme, R.; Schalk, R. Different or Alike? Exploring the Psychological Contract and Commitment of Different Generations of Hospitality Workers. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 553–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, C.J.; Rubin, B.A. Generational Differences in the Effects of Insecurity, Restructured Workplace Temporalities, and Technology on Organizational Loyalty. Sociol. Spectr. 2011, 31, 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamm, E.; Meeks, M.D. Workplace Fun: The Moderating Effects of Generational Differences. Empl. Relat. 2009, 31, 613–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Peeters, M.C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Hetland, J. Crafting a Job on a Daily Basis: Contextual Correlates and the Link to Work Engagement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 1120–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Job Crafting: Towards a New Model of Individual Job Redesign. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2010, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Job Crafting and Job Performance: A Longitudinal Study. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2014, 24, 914–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Derks, D.; Bakker, A.B. Job Crafting and Its Relationships with Person–Job Fit and Meaningfulness: A Three-Wave Study. J. Voc. Behav. 2016, 92, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slemp, G.R.; Kern, M.L.; Vella-Brodrick, D.A. Workplace Well-Being: The Role of Job Crafting and Autonomy Support. Psychol. Well-Being 2015, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Im, J.; Qu, H. Exploring Antecedents and Consequences of Job Crafting. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wingerden, J.; Derks, D.; Bakker, A.B. The Impact of Personal Resources and Job Crafting Interventions on Work Engagement and Performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 56, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Hur, W.M.; Choi, W.H. Coworker support as a double-edged sword: A moderated mediation model of job crafting, work engagement, and job performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 31, 1417–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.; Yi, O. Hotel employee job crafting, burnout, and satisfaction: The moderating role of perceived organizational support. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 72, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harju, L.K.; Hakanen, J.J.; Schaufeli, W.B. Can job crafting reduce job boredom and increase work engagement? A three-year cross-lagged panel study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 95, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass, S.J.; Vodanovich, S.J.; Callender, A. State-trait boredom: Relationship to absenteeism, tenure, and job satisfaction. J. Bus. Psychol. 2001, 16, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulas, W.L.; Vodanovich, S.J. The essence of boredom. Psychol. Rec. 1993, 43, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Barbalet, J.M. Boredom and Social Meaning. Br. J. Sociol. 1999, 50, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, C.D. Boredom at Work: A Neglected Concept. Hum. Relat. 1993, 46, 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V. Analysis of Employee Engagement and Its Predictors. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. 2011, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, M. Predictors of Job Boredom. Honors Undergraduate Thesis, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bruursema, K.; Kessler, S.R.; Spector, P.E. Bored Employees Misbehaving: The Relationship between Boredom and Counterproductive Work Behaviour. Work Stress 2011, 25, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cardona, I.; Vera, M.; Martínez-Lugo, M.; Rodríguez-Montalbán, R.; Marrero-Centeno, J. When the Job Does Not Fit: The Moderating Role of Job Crafting and Meaningful Work in the Relation between Employees’ Perceived Overqualification and Job Boredom. J. Career Assess. 2019, 28, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, M.L.; Gao, F.; Thornburg, K.M. Boredom in the Workplace. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2015, 58, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acee, T.W.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.-I.; Chu, H.-N.R.; Kim, M.; Cho, Y.J.; Wicker, F.W. Academic Boredom in under- and over-Challenging Situations. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 35, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harju, L.K.; Hakanen, J.J. An Employee Who Was Not There: A Study of Job Boredom in White-Collar Work. Pers. Rev. 2016, 45, 374–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijseger, G.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Taris, T.W.; van Beek, I.; Ouweneel, E. Watching the Paint Dry at Work: Psychometric Examination of the Dutch Boredom Scale. Anxiety Stress Coping 2013, 26, 508–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Bakker, A.B.; van den Heuvel, M. Weekly Job Crafting and Leisure Crafting: Implications for Meaning-Making and Work Engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 90, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baratta, P.; Spence, J.R. Do Bored Employees Job Craft When Demands and Resources Are Low? Acad. Manag. Proc. 2017, 2017, 14363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hooff, M.L.; van Hooft, E.A. Boredom at Work: Proximal and Distal Consequences of Affective Work-Related Boredom. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, S.K.; Ohly, S. Designing Motivating Jobs: An Expanded Framework for Linking Work Characteristics and Motivation. In Work Motivation: Past, Present, and Future; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 233–284. [Google Scholar]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Brauchli, R.; Jenny, G.J.; Bauer, G.F. The Consequences of Job Crafting: A Three-Wave Study. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2015, 25, 353–362. [Google Scholar]

- Bindl, U.K.; Parker, S. Proactive Work Behavior: Forward-Thinking and Change-Oriented Action in Organizations. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Angeline, T. Managing Generational Diversity at the Workplace: Expectations and Perceptions of Different Generations of Employees. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 249–255. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, S.; Kuron, L. Generational Differences in the Workplace: A Review of the Evidence and Directions for Future Research. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 35, S139–S157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemiec, S. Finding Common Ground for All Ages. Secur. Distrib. Mark. 2000, 30, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, M. Culture and Commitment: A Study of the Generation Gap; Panther: St. Albans, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Codrington, G. Detailed Introduction to Generational Theory. J. Human Resour. Sustain. Stud. 2021, 9, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hemlin, S.; Allwood, C.M.; Martin, B.R.; Mumford, M.D. Creativity and Leadership in Science, Technology, and Innovation; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, W.; Howe, N. Generations the History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069; Quill: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Scandura, T.A.; Williams, E.A. Research Methodology in Management: Current Practices, Trends, and Implications for Future Research. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 1248–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Kim, M.; Han, H.-S.; Holland, S. The Determinants of Hospitality Employees’ pro-Environmental Behaviors: The Moderating Role of Generational Differences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.C.; Gursoy, D. Impact of Job Burnout on Satisfaction and Turnover Intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2013, 40, 210–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, A.; Herzfeldt, R. Learning Orientation, Organizational Commitment and Talent Retention across Generations. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 929–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Gursoy, D. Generation Effects on Work Engagement among U.S. Hotel Employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1195–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowske, B.J.; Rasch, R.; Wiley, J. Millennials’ (Lack of) Attitude Problem: An Empirical Examination of Generational Effects on Work Attitudes. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M. A Review of the Empirical Evidence on Generational Differences in Work Attitudes. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemke, R.; Raines, C.; Filipczak, B. Generations at Work: Managing The Clash of Veterans, Boomers, Xers, and Nexters in Your Workplace; AMACOM: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jurkiewicz, C.L. Generation X and the Public Employee. Public Pers. Manag. 2000, 29, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulgan, B. Managing Generation X How to Bring out the Best in Young Talent; W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Orme, D. A Corporate Cultivator’s Guide to Growing Leaders. New Zealand Management: The Leaders’ Magazine, 24 August 2004; 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D.; Maier, T.A.; Chi, C.G. Generational Differences: An Examination of Work Values and Generational Gaps in the Hospitality Workforce. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostanek, E.; Khoreva, V. Multi-Generational Workforce and Its Implication for Talent Retention Strategies. Psychol. Retent. 2018, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupperschmidt, B.R. Multigeneration Employees: Strategies for Effective Management. Health Care Manag. 2000, 19, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dries, N.; Pepermans, R.; De Kerpel, E. Exploring Four Generations’ Beliefs about Career. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 907–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, B. Baby Boomers, Generation X and Generation Y? Foresight 2003, 5, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.; Maier, T.A.; Gursoy, D. Employees’ Perceptions of Younger and Older Managers by Generation and Job Category. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, S.M. Generational Differences in Psychological Traits and Their Impact on the Workplace. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 862–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hauw, S.; De Vos, A. Millennials’ Career Perspective and Psychological Contract Expectations: Does the Recession Lead to Lowered Expectations? J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goman, C.K. Communicating for a new age. Strateg. Commun. Manag. 2006, 10, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Jurkiewicz, C.L.; Brown, R.G. Generational Comparisons of Public Employee Motivation. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 1998, 18, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickson, S. The Impact of Identity Orientation on Individual and Organizational Outcomes in Demographically Diverse Settings. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A.; Terry, D.I. Social Identity and Self-Categorization Processes in Organizational Contexts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutell, N.J.; Wittig-Berman, U. Work-Family Conflict and Work-Family Synergy for Generation X, Baby Boomers, and Matures. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and Validation of the Job Crafting Scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J.; Tims, M. Crafting Your Career: How Career Competencies Relate to Career Success via Job Crafting. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 66, 168–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.-M.; Moon, T.-W.; Choi, W.-H. The Role of Job Crafting and Perceived Organizational Support in the Link between Employees’ CSR Perceptions and Job Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 40, 3151–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernerth, J.B.; Aguinis, H. A Critical Review and Best-Practice Recommendations for Control Variable Usage. Pers. Psychol. 2015, 69, 229–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, J. BAM2019 Conference Proceedings. In Gender and Job Crafting: Understanding the Role of Gendered Behaviours in the Abilities and Motivations to Proactively Craft Work; British Academy of Management: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Oprea, B.; Iliescu, D.; Burtăverde, V.; Dumitrache, M. Personality and Boredom at Work: The Mediating Role of Job Crafting. Career Dev. Int. 2019, 24, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harju, L.K.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Hakanen, J.J. A Multilevel Study on Servant Leadership, Job Boredom and Job Crafting. J. Manag. Psychol. 2018, 33, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, D.P.; Finkelstein, L.M. Generationally Based Differences in the Workplace: Is There a There There? Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 8, 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriac, J.P.; Woehr, D.J.; Banister, C. Generational Differences in Work Ethic: An Examination of Measurement Equivalence across Three Cohorts. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, E.; Urwin, P. Generational Differences in Work Values: A Review of Theory and Evidence. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabey, C.N.; Kerse, G. The Relationship between Job Crafting and Psychological Capital: A Survey in a Manufacturing Business. Pressacad. Proc. 2017, 3, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzi, L. Network Characteristics: When an Individual’s Job Crafting Depends on the Jobs of Others. Hum. Relat. 2016, 70, 436–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | Respondents (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 192 | 60.0 |

| Male | 128 | 40.0 |

| Age (birth year) | ||

| Gen X (1961–1981) | 172 | 53.7 |

| Gen Y (1982–2004) | 148 | 46.3 |

| Education | ||

| Associate degree/high school | 29 | 9.0 |

| Undergraduate | 247 | 77.2 |

| Graduate | 44 | 13.8 |

| Tested Model | χ2 | p | df | GFI | CFI | RMSEA | IFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job crafting (first order) | 738.837 | 0.01 | 183 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.06 | 0.89 |

| Job crafting (second order) | 706.323 | 0.01 | 189 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.06 | 0.89 |

| Job boredom (first order) | 26.126 | 0.01 | 9 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.05 | 0.90 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1. Job crafting | 3.69 | 0.63 | (0.90) | ||

| 2.2. Job boredom | 2.43 | 0.68 | −0.63 ** | (0.91) | |

| 3.3. Generational diversity | 0.52 | 0.49 | −0.23 ** | 0.14 * | - |

| Variables | Coeff. | SE | C.R. | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.214 | 0.060 | −3.574 | 0.000 | −0.334 | −0.082 |

| Gender | −0.026 | 0.091 | −0.289 | 0.773 | −0.189 | 0.127 |

| Education level | 0.078 | 0.112 | 0.698 | 0.485 | −0.129 | 0.285 |

| Job crafting | −0.407 | 0.030 | −13.559 | 0.000 | −0.461 | −0.346 |

| Generation | 0.187 | 0.037 | 5.104 | 0.000 | 0.116 | 0.265 |

| Interaction | 0.130 | 0.035 | 2.554 | 0.011 | 0.028 | 0.191 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sesen, H.; Donkor, A.A. Job Crafting, Job Boredom and Generational Diversity: Are Millennials Different from Gen Xs? Sustainability 2023, 15, 5058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065058

Sesen H, Donkor AA. Job Crafting, Job Boredom and Generational Diversity: Are Millennials Different from Gen Xs? Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):5058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065058

Chicago/Turabian StyleSesen, Harun, and Ama Asantewaa Donkor. 2023. "Job Crafting, Job Boredom and Generational Diversity: Are Millennials Different from Gen Xs?" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 5058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065058

APA StyleSesen, H., & Donkor, A. A. (2023). Job Crafting, Job Boredom and Generational Diversity: Are Millennials Different from Gen Xs? Sustainability, 15(6), 5058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065058