The Impacts of the Asian Elephants Damage on Farmer’s Livelihood Strategies in Pu’er and Xishuangbanna in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework and Econometric Approach

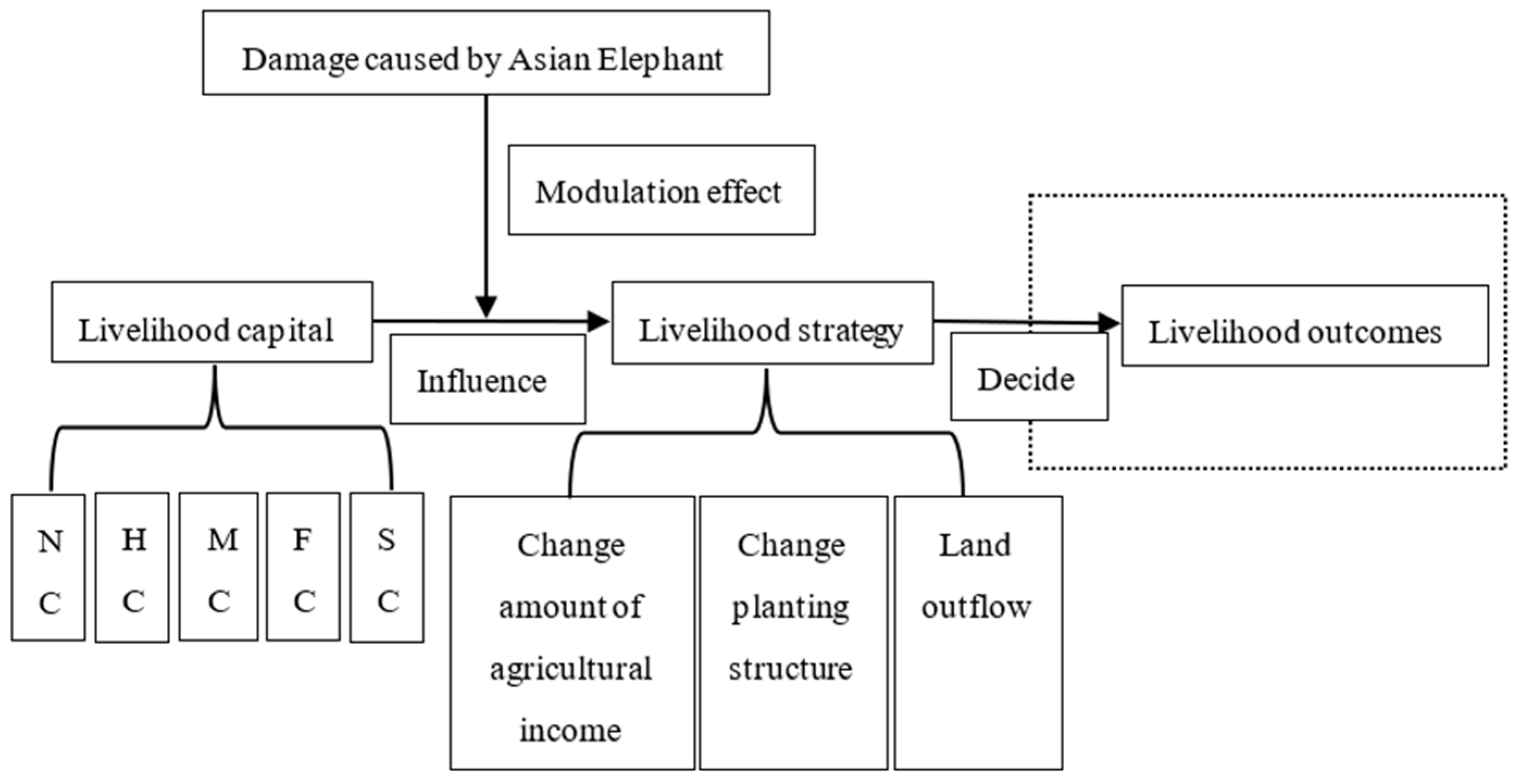

2.1. Conceptual Framework Based on the Sustainable Livelihood Analysis Framework

2.2. Empirical Model Specification

2.2.1. Binary Logit Regression Analysis Method

2.2.2. Modulation Effect

3. Data and Descriptive Statistics

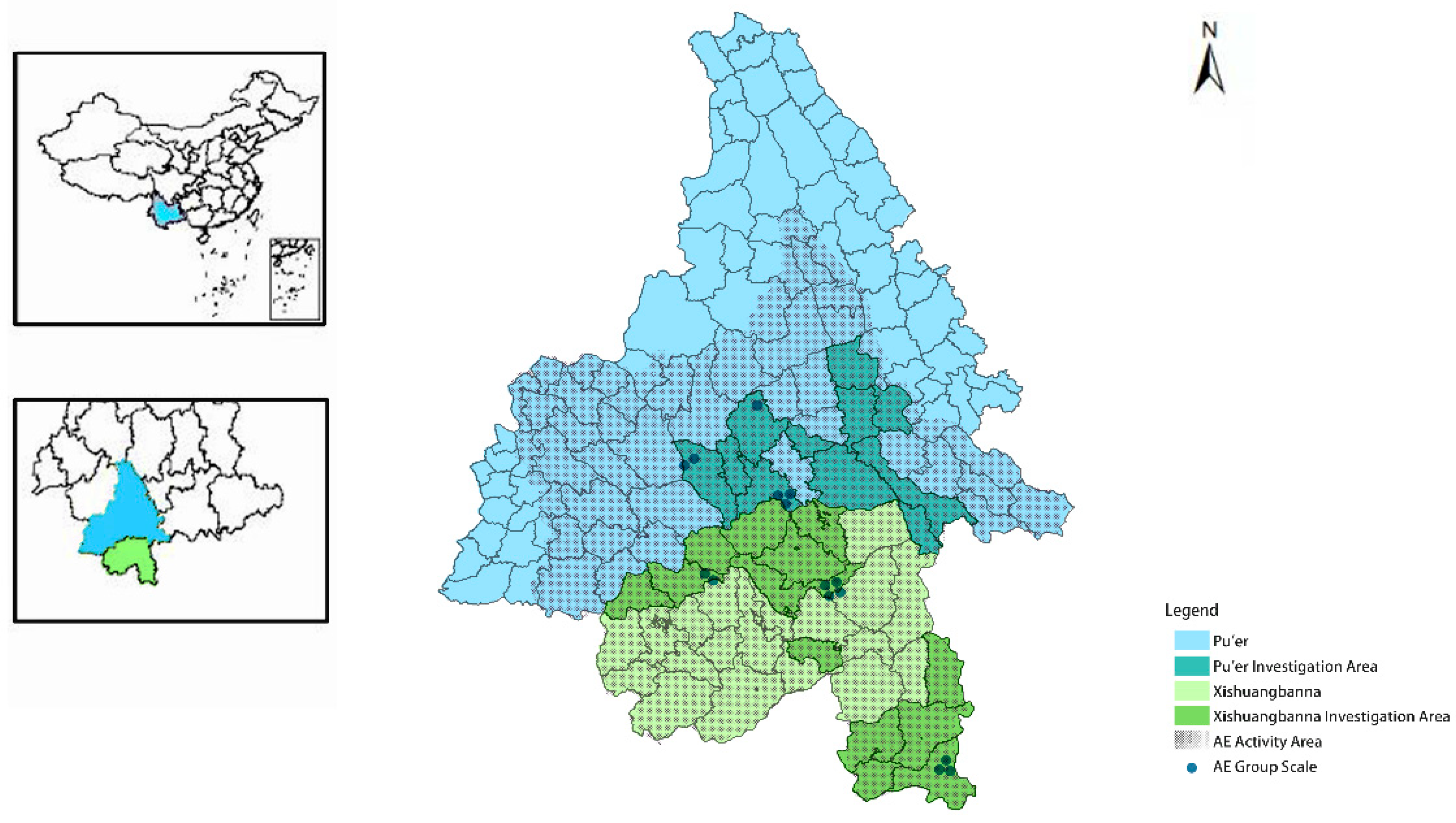

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Description

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parker, G.E.; Osborn, F.V.; Hoarse, R.E. Human-Elephant Conflict Mitigation: A Training Course for Community-Based Approaches in Africa (Participant’s Manual). 2007. Available online: https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=GB2013203085 (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Shaffer, L.J.; Khadka, K.K.; Van Den Hoek, J.; Naithani, K.J. Human-Elephant Conflict: A Review of Current Management Strategies and Future Directions. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 6, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thouless, C.; Dublin, H.T.; Blanc, J.; Skinner, D.P.; Daniel, T.E.; Taylor, R.; Maisels, F.; Frederick, H.; Bouché, P. African Elephant Status Report 2016. Species Surviv. Comm. 2016, 60, 309. [Google Scholar]

- Nyhus, P.J. Human–Wildlife Conflict and Coexistence. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 143–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodroffe, R.; Thirgood, S.; Rabinowitz, A. People and Wildlife, Conflict or Co-Existence? Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Ntukey, L.T.; Munishi, L.K.; Kohi, E.; Treydte, A.C. Land Use/Cover Change Reduces Elephant Habitat Suitability in the Wami Mbiki–Saadani Wildlife Corridor, Tanzania. Land 2022, 11, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Zheng, X.; Lv, T.; Jiang, G.; Tang, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, M. Population dynamics of Asian elephant in Xishuangbanna Pu’er. For. Constr. 2019, 6, 85–90. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, P.; Macandza, V.; Goba, P.; Mourinho, J.; Roque, D.; Mamugy, F.; Langa, B. Assessing Tolerance for Wildlife: Human-Elephant Conflict in Chimanimani, Mozambique. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2021, 26, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoare, R.E. Determinants of Human–Elephant Conflict in a Land-Use Mosaic. J. Appl. Ecol. 1999, 36, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y. Ecological Labeling and Wildlife Conservation: Citizens’ Perceptions of the Elephant Ivory-Labeling System in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 702, 134709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinsella, J.; Wilson, S.; De Jong, F.; Renting, H. Pluriactivity as a Livelihood Strategy in Irish Farm Households and Its Role in Rural Development. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, W.M.; Hutton, J. People, Parks and Poverty. Conserv. Soc. 2007, 5, 147–183. [Google Scholar]

- Barua, M.; Bhagwat, S.A.; Jadhav, S. The Hidden Dimensions of Human–Wildlife Conflict: Health Impacts, Opportunity and Transaction Costs. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 157, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyirenda, V.R.; Nkhata, B.A.; Tembo, O.; Siamundele, S. Elephant Crop Damage: Subsistence Farmers’ Social Vulnerability, Livelihood Sustainability and Elephant Conservation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, C.; Leimgruber, P.; Rodriguez, S.; McEvoy, J.; Sotherden, E.; Tonkyn, D. Perception of Human–Elephant Conflict and Conservation Attitudes of Affected Communities in Myanmar. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2019, 12, 1940082919831242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.L. Labor Costs and Crop Protection from Wildlife Predation: The Case of Elephants in Gabon. Agric. Econ. 2012, 43, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.D.; Ochieng, T. Uptake and Performance of Farm-Based Measures for Reducing Crop Raiding by Elephants Loxodonta Africana among Smallholder Farms in Laikipia District, Kenya. Oryx 2008, 42, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitati, N.; Walpole, M.; Leader-Williams, N.; Stephenson, P.J. Human–Elephant Conflict: Do Elephants Contribute to Low Mean Grades in Schools within Elephant Ranges. IJBC 2012, 4, 614–620. [Google Scholar]

- Nyumba, T.O. Are Elephants Flagships or Battleships? Understanding Impacts of Human-Elephant Conflict on Human Wellbeing in Trans Mara District, Kenya. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Machimu, G.M.; Kayunze, K.A. Impact of Sugarcane Contract Farming Arrangements on Smallholder Farmers’ Livelihood Outcomes in Kilombero Valley, Tanzania. EAJ-SAS 2019, 1, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hinks, T.; Gruen, C. What Is the Structure of South African Happiness Equations? Evidence from Quality of Life Surveys. Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 82, 311–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossouw, S.; Naudé, W. The Non-Economic Quality of Life on a Sub-National Level in South Africa. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 86, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalos, A.; Ferriss, A.L.; Easterlin, R.; Patrick, D.; Pavot, W. The Quality of Life (QOL) Research Movement: Past, Present, and Future. Soc. Indic. Res. 2006, 76, 343–466. [Google Scholar]

- Thant, Z.M.; May, R.; Røskaft, E. Pattern and Distribution of Human-Elephant Conflicts in Three Conflict-Prone Landscapes in Myanmar. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 25, e01411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis; IDS Working Paper 72; IDS: Brighton, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dorward, A.; Anderson, S.; Bernal, Y.N.; Vera, E.S.; Rushton, J.; Pattison, J.; Paz, R. Hanging in, Stepping up and Stepping out: Livelihood Aspirations and Strategies of the Poor. Dev. Pract. 2009, 19, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, H.G.; Pender, J.; Damon, A.; Wielemaker, W.; Schipper, R. Policies for Sustainable Development in the Hillside Areas of Honduras: A Quantitative Livelihoods Approach. Agric. Econ. 2006, 34, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhuo, R.; Xie, D.; Zhang, Y. Land use of farmers with different livelihood types—An Empirical Study of typical villages in the Three Gorges Reservoir area. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2010, 65, 1401–1410. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dhakal, B.; Thapa, B. Residents’ Perceptions of Human–Elephant Conflict: Case Study in Bahundangi, Nepal. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, A.-M.; Papo, S.; Rodriguez, A.; Smith, J.S. Antigenic Analysis of Rabies-Virus Isolates from Latin America and the Caribbean. Thai J. Vet. Med. Ser. B 1994, 41, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashley, C.; Carney, D. Sustainable Livelihoods: Lessons from Early Experience; Department for International Development: London, UK, 1999; ISBN 978-0-85003-419-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rakodi, C. A Capital Assets Framework for Analysing Household Livelihood Strategies: Implications for Policy. Dev. Policy 1999, 17, 315–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlauf, S.N.; Fafchamps, M. Empirical Studies of Social Capital: A Critical Survey. 2003. Available online: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:cfd0256d-9409-4538-8fca-0e019df36ca7/download_file?file_format=application%2Fpdf&safe_filename=wp2003-12.pdf&type_of_work=Working+paper (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- You Jun, Li Xiaobing Study on the mechanism of industrial poverty alleviation and benefit from the perspective of livelihood response—A case study of Weng’an county, Guizhou Province. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2019, 40, 185–192. (In Chinese)

- Chen, Z.; Xu, J.; Wu, W. Analysis on livelihood capital difference and livelihood satisfaction of different types of farmers in collective forest area. For. Econ. 2014, 36, 36–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.; Bidwell, P.; Sillero-Zubiri, C. A Review of Human-Elephant Conflict Management Strategies. In People & Wildlife, A Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Born Free Foundation Partnership; 2003; Available online: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/85104052/00b7d529f54e5db014000000.pdf?1651141809=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DA_review_of_human_elephant_conflict_mana.pdf&Expires=1678531116&Signature=Muc~h4LEAL6oVXbYJupluXD9DsD2FaawMOfLbFSD9B (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Dublin, H.T.; Hoare, R.E. Searching for Solutions: The Evolution of an Integrated Approach to Understanding and Mitigating Human–Elephant Conflict in Africa. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2004, 9, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.J.; DeFries, R. Ecological Mechanisms Linking Protected Areas to Surrounding Lands. Ecol. Appl. 2007, 17, 974–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.S.F.; Chase, M.J.; Rogers, T.L.; Leggett, K.E.A. Taking the Elephant out of the Room and into the Corridor: Can Urban Corridors Work? Oryx 2017, 51, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittiglio, C.; Skidmore, A.K.; van Gils, H.A.; McCall, M.K.; Prins, H.H. Smallholder Farms as Stepping Stone Corridors for Crop-Raiding Elephant in Northern Tanzania: Integration of Bayesian Expert System and Network Simulator. Ambio 2014, 43, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puyravaud, J.-P.; Cushman, S.A.; Davidar, P.; Madappa, D. Predicting Landscape Connectivity for the Asian Elephant in Its Largest Remaining Subpopulation. Anim. Conserv. 2017, 20, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakholi, L. Modes of Land Control in Transfrontier Conservation Areas: A Case of Green Grabbing. Master’s Thesis, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, K.; Mondal, J. Perceptions and Patterns of Human–Elephant Conflict at Barjora Block of Bankura District in West Bengal, India: Insights for Mitigation and Management. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 15, 547–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, G.; Dhakal, M.; Pradhan, N.M.B.; Leverington, F.; Hockings, M. Nature and Extent of Human–Elephant Elephas Maximus Conflict in Central Nepal. Oryx 2016, 50, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayechew, B.; Tolcha, A. Assessment of Human-Wildlife Conflict in and Around Weyngus Forest, Dega Damot Woreda, West Gojjam Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. IJSES 2020, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell-Rodwell, C.E.; Rodwell, T.; Rice, M.; Hart, L.A. Living with the Modern Conservation Paradigm: Can Agricultural Communities Co-Exist with Elephants? A Five-Year Case Study in East Caprivi, Namibia. Biol. Conserv. 2000, 93, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karidozo, M.; Osborn, F.V. Community Based Conflict Mitigation Trials: Results of Field Tests of Chilli as an Elephant Deterrent. JBES 2015, 3, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Le Bel, S.; La Grange, M.; Drouet, N. Repelling Elephants with a Chilli Pepper Gas Dispenser: Field Tests and Practical Use in Mozambique, Zambia and Zimbabwe from 2009 to 2013. Pachyderm 2015, 56, 87–96. Available online: https://agritrop.cirad.fr/578356/1/578356.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- He, Q.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, W.; Dong, R. Perception and Attitudes of Local Communities towards Wild Elephant-Related Problems and Conservation in Xishuangbanna, Southwestern China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2011, 21, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.S.; Andelman, S.J.; Bakarr, M.I.; Boitani, L.; Brooks, T.M.; Cowling, R.M.; Fishpool, L.D.; Da Fonseca, G.A.; Gaston, K.J.; Hoffmann, M. Effectiveness of the Global Protected Area Network in Representing Species Diversity. Nature 2004, 428, 640–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable Name | Variable Assignment | Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Y1 Change amount of agricultural income | 0 = reduce dependence 1 = maintain the status 2 = strengthen dependence | |

| Y2 Change planting structure | 0 = no change 1 = change | |

| Y3 Land outflow | 0 = no change 1 = change | |

| L1 Human capital | ||

| Health status | 1 = very good 2 = good 3 = general 4 = have ailment 5 = have serious disease | 0.28 |

| Amount of labor force in household population | Actual survey data | 0.07 |

| Education level | 1 = primary school or below 2 = junior high school 3 = high school 4 = college 5 = master degree or above | 0.49 |

| Village cadre | 1 = Yes 2 = Used to be 3 = No | 0.15 |

| L2 Natural capital | ||

| Per capita cultivated land area | Actual survey data | 0.51 |

| Per capita Forest land area. | Actual survey data | 0.49 |

| L3 Material capital | ||

| The number of family houses | Actual survey data | 0.01 |

| The number of transportations | Actual survey data | 0.16 |

| The number of production machines and tools | Actual survey data | 0.83 |

| L4 Finical capital | ||

| Having loans | 0 = no 1 = yes | 0.24 |

| Having borrowings | 0 = no 1 = yes | 0.66 |

| Obtained insurance | 0 = no 1 = yes | 0.10 |

| L5 Social capital | ||

| Difficulty of borrowing from relatives and friends | 1 = a lot of 2 = many 3 = general 4 = less 5 = very seldom | 0.16 |

| Degree of trust between relatives and friends | 1 = great trust 2 = trust 3 = general 4 = distrust 5 = very distrustful | 0.25 |

| Degree of trust in villagers | 1 = great trust 2 = trust 3 = general 4 = distrust 5 = very distrustful | 0.08 |

| Participation in collective, wedding and funeral activities | 1 = very high 2 = high 3 = general 4 = low 5 = very low | 0.24 |

| Villagers’ help and communication | 1 = very high 2 = high 3 = general 4 = low 5 = very low | 0.27 |

| X1 Subjective Asian elephant damage | 1 = least serious 2 = a little serious 3 = neutral 4 = serious 5 = very serious | |

| X2 Objective Asian elephant damage | Actual survey data |

| Livelihood Strategy Selection | Y1 Change Amount of Agricultural Income | Y2 Change Planting Structure | Y3 Land Outflow | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Err. | Coef. | Std. Err. | Coef. | Std. Err. | |

| L1 | −0.2314482 | 0.1851705 | 0.7562473 ** | 0.4760185 | −0.0713542 | 0.1933015 |

| L2 | 0.0071686 | 0.0048823 | −0.0224544 | 0.0269552 | −0.010532 ** | 0.0059167 |

| L3 | 0.1918159 ** | 0.1140615 | 0.4914612 ** | 0.2874045 | −0.022121 | 0.1198269 |

| L4 | 0.2855733 | 0.2311592 | 0.2629559 | 0.6503415 | −0.6641393 *** | 0.2571226 |

| L5 | 0.2855733 ** | 0.1578424 | −0.0809522 | 0.4686602 | 0.1210587 | 0.1682161 |

| Prod > chi2 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.02 | |||

| X1 Modulation Effect | Y1 Change Amount of Agricultural Income | Y2 Change Planting Structure | Y3 Land Outflow | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Err. | Coef. | Std. Err. | Coef. | Std. Err. | |

| L1 | 0.1784085 | 0.2840953 | −0.0006072 | 0.8455932 | −0.6494961 | 0.4143797 |

| L2 | −0.0027394 | 0.0065161 | −0.012507 | 0.0471369 | 0.0020528 | 0.0071788 |

| L3 | 0.2581704 | 0.1817919 | 0.0091392 | 0.4833497 | −0.0618001 | 0.2510354 |

| L4 | 0.2393823 | 0.3455573 | −0.5716905 | 1.105245 | 1.129883 ** | 0.4600167 |

| L5 | 0.0030493 | 0.1837158 | 0.1780317 | 0.587834 | −0.4361593 * | 0.2533164 |

| Prod > chi2 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | |||

| X2 Modulation Effect | Y1 Change Amount of Agricultural Income | Y2 Change Planting Structure | Y3 Land Outflow | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Err. | Coef. | Std. Err. | Coef. | Std. Err. | |

| L1 | −0.3519292 | 0.9356026 | −2.282997 | 3.399837 | −0.6069449 | 0.7646385 |

| L2 | 0.048185 ** | 0.0250428 | −0.0396047 | 0.1218744 | 0.0592259 ** | 0.0287386 |

| L3 | −2.062123 *** | 0.7542621 | −1.669317 | 2.334429 | −0.250099 | 0.5613632 |

| L4 | −0.4298687 | 0.7147174 | 0.5796835 | 1.279546 | −0.3332165 | 0.4855941 |

| L5 | −0.1333688 | 0.576897 | 0.6479888 | 1.842415 | 0.0836777 | 0.3919103 |

| Prod > chi2 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.03 | |||

| Modulation Effect | Y1 Change Amount of Agricultural Income | Y2 Change Planting Structure | Y3 Land Outflow | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Err. | Coef. | Std. Err. | Coef. | Std. Err. | |

| X1 | −0.0329467 | 0.033588 | −0.032798 | 0.1792023 | 0.0622442 | 0.0484823 |

| X2 | 0.2601678 ** | 0.1042488 | −0.1836357 | 0.5162698 | 0.1912931 ** | 0.0762499 |

| Prod > chi2 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.02 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Du, Y.; Chen, J.; Xie, Y. The Impacts of the Asian Elephants Damage on Farmer’s Livelihood Strategies in Pu’er and Xishuangbanna in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065033

Du Y, Chen J, Xie Y. The Impacts of the Asian Elephants Damage on Farmer’s Livelihood Strategies in Pu’er and Xishuangbanna in China. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):5033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065033

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Yuchen, Junfeng Chen, and Yi Xie. 2023. "The Impacts of the Asian Elephants Damage on Farmer’s Livelihood Strategies in Pu’er and Xishuangbanna in China" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 5033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065033

APA StyleDu, Y., Chen, J., & Xie, Y. (2023). The Impacts of the Asian Elephants Damage on Farmer’s Livelihood Strategies in Pu’er and Xishuangbanna in China. Sustainability, 15(6), 5033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065033