Semi-Acquaintance Society in Rural Community-Based Tourism: Case Study of Moon Village, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Community-Based Rural Tourism Development

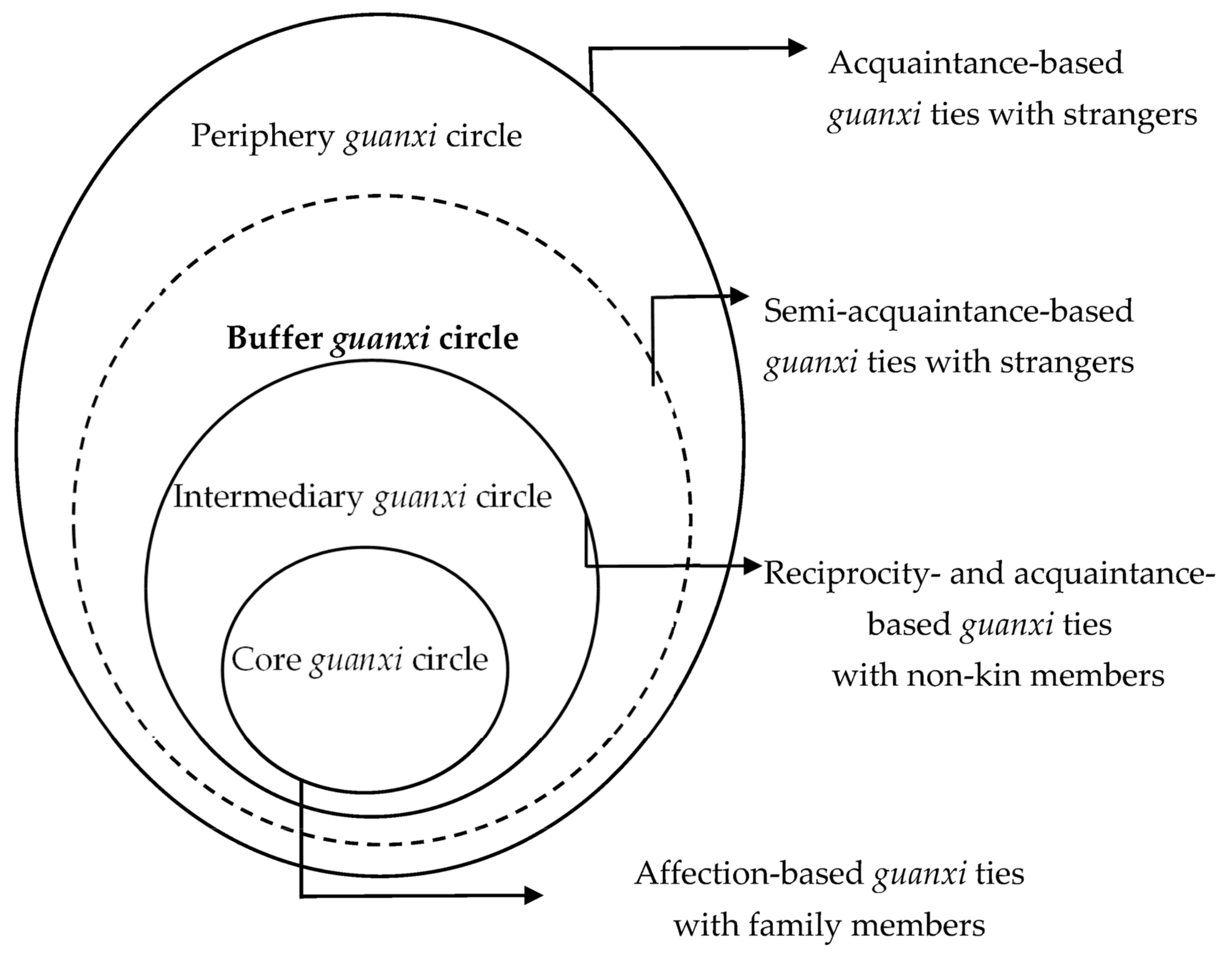

2.2. Guanxi in Community-Based Rural Tourism

3. Research Method

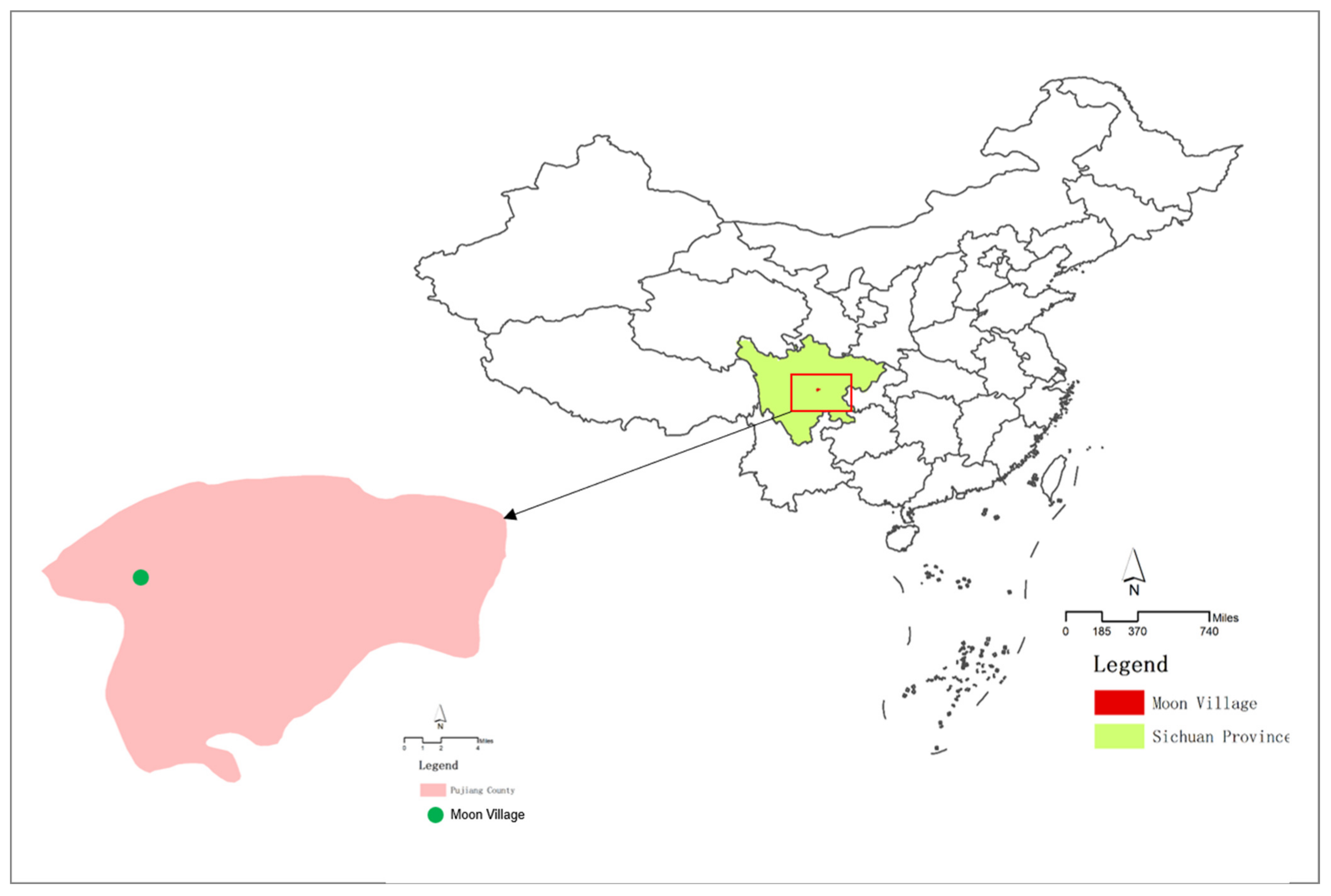

3.1. Case Overview and the Selection of Moon Village

3.2. Data Collection and Processing

| Investigation | Date | Participants | Objective | Main Question |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1–7 October 2014 | Management personnel, tourist | Immersive preliminary understanding of the Moon village | What do you think of Moon village? How do you think of its development prospects |

| 2 | 1–3 May 2015 | Tourist | Learn about Moon Village from visitors | What do you think of Moon village? What impresses you most? |

| 3 | 10–25 July 2016 | Tourist, (OR) | Focus on Tourists’ and ORs’ response to development tourism | Tourist: Have you paid any attention to the ORs besides traveling and relaxing? OR: How did you get involved in tourism development? |

| 4 | 6–21 July 2017 | New resident (NR), OR | Focus on their response to each other | NR: Why do you choose to stay? OR: What do you think of the newcomers? |

| 5 | 1–16 September 2018 | Management personnel, NR, OR | Learn about the relationship between the two from the perspective of management | How to get along with others? |

| 6 | 14–18 July 2020 | Management personnel, NR, OR | Focus on their response to each other | How to treat the relationship between each other? |

| 7 | 24–27 February 2023 | NR, OR | Focus on their response to their relationship | NR: How to integrate into the community of ORs? OR: What changes in traditional code of conduct have been brought about by the development of tourism? |

| Label | Gender | Classification | Age | Education | Occupation | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Female | NR | 39 | Graduate student | A member of the project team | |

| B | Female | OR | Undergraduate | Tourism cooperative workers | ||

| C | Male | OR | 30 | Village committee member | ||

| D | Male | NR | 55 | Undergraduate | Cultural and creative worker | |

| E | Male | NR | 40 | Cultural and creative worker, country inn operator | ||

| F | Female | NR | 43 | Cultural and creative worker, seller of tourist souvenirs | ||

| G | Female | NR | Cultural and creative worker, restaurant operator | |||

| H | Male | OR | 23 | College | Tour guide | Homecoming youth, rural tourism cooperative workers |

| I | Female | OR | 26 | Undergraduate | Design studio operator, seller of tourist souvenirs | Homecoming youth |

| J | Female | OR | Restaurant operator | Homecoming youth, rural tourism cooperative workers | ||

| K | Male | OR | 45 | Junior high school | Lei bamboo contractor | Member of Lei Bamboo Cooperative |

| L | Female | OR | 66 | Primary school | - | |

| M | Male | - | 62 | Graduate student | Sociological research specialist | |

| N | Female | - | 45 | Graduate student | Tourism management research expert | |

| O | Male | - | Graduate student | Rural construction research expert | ||

| P | Female | - | 39 | Undergraduate | Administrator |

4. Results and Analysis

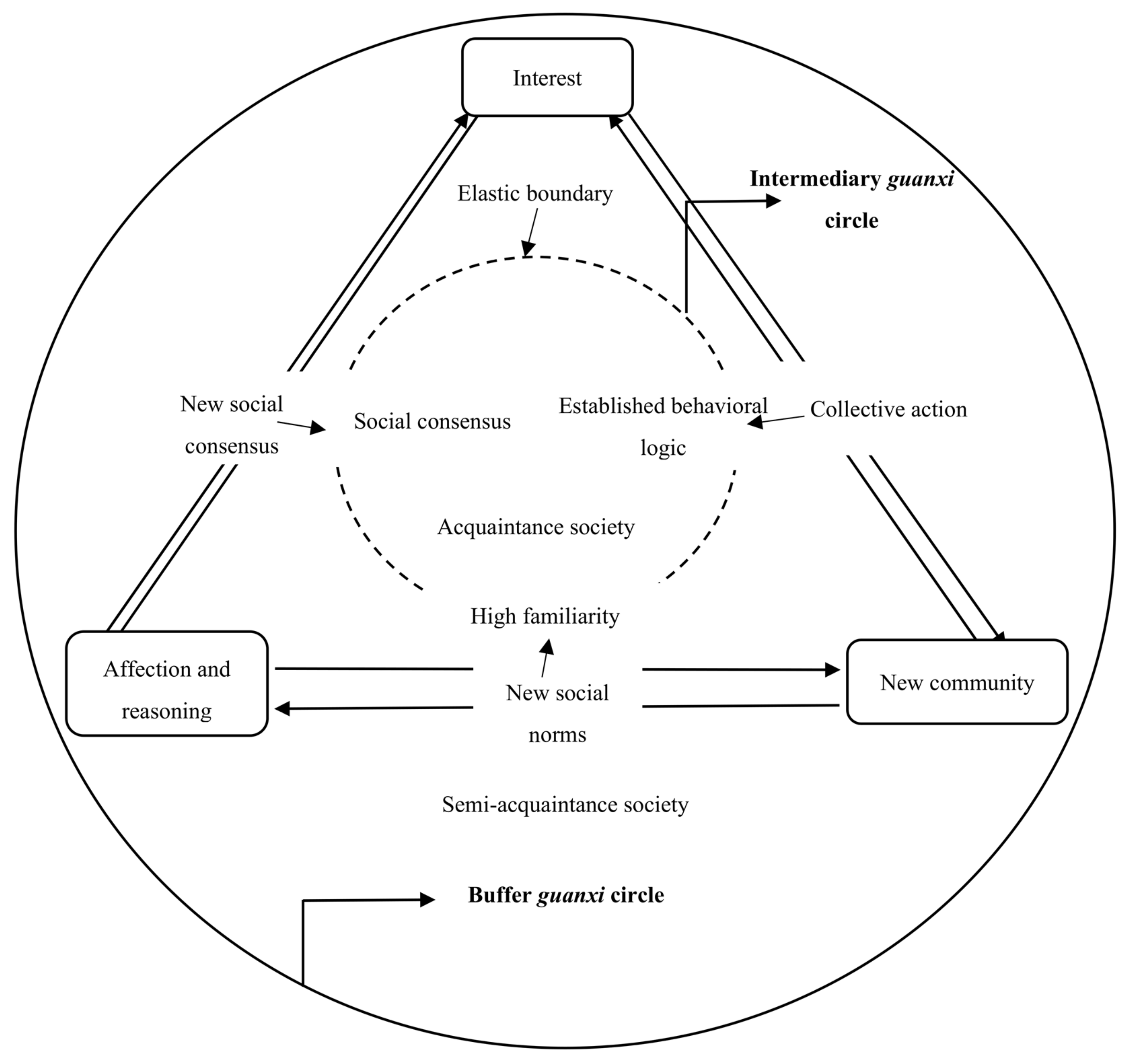

4.1. Embedding of Affection and Reasoning into Community Generates New Social Norms Triggering Familiarity Shock

4.2. Connection between Affection and Reasoning and Interest Condenses Social Consensus Promotes Community Harmony

“In 2014, the first time I came to Moon village, I saw a weather-beaten washstand placed on the threshold of a villager’s house, and its engraved traces deeply attracted me. I insisted on buying it, and the aunt (a local resident) insisted on giving it to me as a gift. When I left, she had put the washstand which is her dowry from 40 years ago in my trunk, the aunt gave it to me (a stranger) just because I said I like it. It was that special encounter that strengthened my affection for this place. Therefore, I came back here to rent and plan for the transformation of a village house into a studio and engaged in cultural and creative work in 2015. I think those who choose to stay here can also feel the kindness, comfort and acceptance of this place just like me. It was also because of the comfort interaction based on affection that retains them”.

4.3. Embedding of Interest into Community Generates Collective Action Reshaping Behavioral Logic

5. Discussion

5.1. From Familiar to Semi-Familiar

5.2. From Old Social Consensus to New Social Consensus

5.3. From Primitive Agrestic Behavioral Logic to Interest-Based Behavioral Logic

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, A.; Yang, Y.; Chen, T.; Liu, J.; Hu, Y. Exploration of spatial differentiation patterns and related influencing factors for National Key Villages for rural tourism in China in the context of a rural revitalization strategy, using GIS-based overlay analysis. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, R. Tourism and the reconfiguration of host group identities: A case study of ethnic tourism in rural Guangxi, China. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2015, 13, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C. Making sense of counter urbanization. J. Rural. Stud. 2004, 20, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahms, F. Settlement evolution in the arena society in the urban field. J. Rural. Stud. 1998, 14, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Tao, Z.; Li, Z.; Wei, H.; Ju, S.; Wang, Z. Research on the types and temporal and spatial characteristics of rural tourist attractions in Jiangsu Province based on GIS technology. Econ. Geogr. 2014, 34, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Ren, Y.; Zhu, D.; Cheng, J.; Yang, X.; Yang, Z.; Yao, G. Research framework and prospects of rural tourism guiding rural revitalization. Geogr. Res. 2019, 38, 102–118. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.E. Tourism: A Community Approach; Methuen: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Idziak, W.; Majewski, J. Community participation in sustainable rural tourism experience creation: A long-term appraisal and lessons from a thematic villages project in Poland. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1341–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.; Tsao, J. Exploring Chinese cultural influences and hospitality marketing relationships. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2000, 12, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.W.; Laws, E.; Buhalis, D. Attracting Chinese outbound tourists: Guanxi and the Australian preferred destination perspective. In Tourism Distribution Channels: Practices, Issues and Transformations; CABI: Glasgow, UK, 2001; pp. 282–297. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.Q. A phenomenological explication of guanxi in rural tourism management: A case study of a village in China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Li, T.H.; Ma, Z.Z.M.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.J.; Chen, N. What influence do regional government officials’ have on tourism related growth? Evid. China Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 2534–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Fennel, S. The role of Tunqin Guanxi in building rural resilience in north China: A case from Qinggang. China Q. 2017, 229, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taormina, R.; Gao, J. A research model for Guanxi behavior: Antecedents, measures, and outcomes of Chinese social networking. Soc. Sci. Res. 2010, 39, 1195–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, E. Can Guanxi be a source of sustained competitive advantage for doing business in China? Acad. Manag. Exec. 1998, 12, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, E.F. From Friendship to Comradeship: The Change in Personal Relations in Communist China. China Q. 1965, 21, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.M. Gifts, Favors, and Banquets: The Art of Social Relationships in China; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.K.; Chiu, S.W. The impact of guanxi positioning on the quality of manufacturer–retailer channel relationships: Evidence from Taiwanese SMEs. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3398–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. Guanxi vs. relationship marketing: Exploring underlying differences. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.B.; Luo, Z.M.; Cheng, X.S.; Li, L. Understanding the interplay of social commerce affordances and swift guanxi: An empirical study. Inf. Manag. 2018, 56, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, A.; Farh, J. Where Guanxi matters—Relational demography and Guanxi in the Chinese context. Work. Occup. 1997, 24, 56–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, A.; Postiglione, G. Guanxi and school success: An ethnographic inquiry of parental involvement in rural China. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2016, 37, 1014–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Woods, M. The role of Guanxi in rural social movements: Two case studies from Taiwan. J. Agrar. Chang. 2013, 13, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X. Social movements in China: Augmenting mainstream theory with Guanxi. Sociology 2017, 51, 111126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.Q.; Liu, P.Y.; Ravenscroft, N.; Su, S.P. Changing community relations in southeast China: The role of Guanxi in rural environmental governance. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 833–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Wang, H.W.; Wang, G.H.; Li, W. Opinion evolution in different social acquaintance networks. Chaos 2017, 27, 113111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Lai, K.; Feng, X. The problem of ‘guanxi’ for actualizing community tourism: A case study of relationship networking in China. Tour. Geogr. 2007, 9, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Ryan, C.; Wang, D.G. China’s Village Tourism Committees: A Social Network Analysis. J. Travel Res. 2020, 60, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, P.; Bao, J. Patroneclient ties in tourism: The case study of Xidi, China. Tour. Geogr. 2009, 11, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Peng, Q. A content analysis of corporate social responsibility: Perspectives from China’s top 30 hotel-management companies. Hosp. Soc. 2016, 6, 153–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Ryan, C.; Bin, L.; Wei, G. Political connections, guanxi and adoption of CSR policies in the Chinese hotel industry: Is there a link? Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ap, J. Factors affecting tourism policy implementation: A conceptual framework and a case study in China. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.N.; Timothy, D.J. Governance of red tourism in China: Perspectives on power and guanxi. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Dwyer, L. Residents’ place satisfaction and place attachment on destination brand-building behaviors: Conceptual and empirical differentiation. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 1026–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.C.; Dwyer, L.; Firth, T. Residents’ place attachment and word-of-mouth behaviours: A tale of two cities. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.C.; Hall, C.M.; Prayag, G. Sense of Place and Place Attachment in Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, L.; Chen, N.; Lee, J. The role of place attachment in tourism research. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, T.B. After comradeship: Personal relations in China since the cultural revolution. China Q. 1985, 104, 657–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, H.; Ames, R. Anticipating China: Thinking through the Narratives of Chinese and Western Culture; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.Q.; Nordin, A.H. Relationality and rationality in Confucian and Western traditions of thought. Camb. Rev. Int. Aff. 2019, 32, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D.G. Alternative Tourism: Concepts, Classifications, and Questions; Smith, V.L., Eadington, W.R., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Curry, N. Community participation and rural policy: Representativeness in the development of Millennium Greens. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2001, 44, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, J.A.P. Governmental responses to tourism development: Three Brazilian case studies. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, P.T.; Perdue, R.R.; Allen, L. Rural resident tourism perceptions and attitudes by community level of tourism. J. Travel Res. 1990, 28, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.; Getz, D. Collaboration theory and community tourism planning. Ann. Tour. Res. 1995, 22, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, H.; Prideaux, B. An alternative approach to community-based ecotourism: A bottom-up locally initiated non-monetised project in Papua New Guinea. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 880–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, N.B. Community-based cultural tourism: Issues, threats and opportunities. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatipoglu, B.; Alvarez, M.D.; Ertuna, B. Barriers to stakeholder involvement in the planning of sustainable tourism: The case of the Thrace region in Turkey. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.; Hafer, H.; Long, P.; Perdue, R. Rural residents’ attitudes toward recreation and tourism development. J. Travel Res. 1993, 31, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.S.; Morais, D.P. Factions and enclaves: Small towns and socially unsustainable tourism development. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGehee, N.G.; Andereck, K.L. Factors predicting rural residents’ support of tourism. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.E. Perceptions and attitudes of decision making groups in tourism centers. J. Travel Res. 1983, 21, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeldner, C.R.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Tourism: Principles, Practices, Philosophies, 9th ed; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, C.; Ladkin, A.; Fletcher, J. Stakeholder collaboration and heritage management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearing, S.; McDonald, M. The development of community-based tourism: Re-thinking the relationship between tour operators and development agents as intermediaries in rural and isolated area communities. J. Sustain. Tour. 2002, 10, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, C.; Simmons, D. Community adaptation to tourism: Comparisons between Rotorua and Kaikoura, New Zealand. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S.; Page, S.J. Destination Marketing Organizations and Destination Marketing: A Narrative Analysis of the Literature. Tour. Manag. 2014, 41, 202–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafieisabet, N.; Haratifard, S. Community-Based Tourism: An Approach for Sustainable Rural Development (Case Study: Asara district, Chalous Road). J. Sustain. Rural. Dev. 2019, 3, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, T.; Zhou, Y. Community, Governments and External Capitals in China’s Rural Cultural Tourism: A Comparative Study of Two Adjacent Villages. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Chen, G.; Ma, L. Tourism research in China: Insights from insiders. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 45, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.T. From the Soil: The foundations of Chinese Society; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, X.T. Peasant Life in China: A Field Study of Country Life in the Yangtze Valley; Routledge: London, UK; Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, X.T.; Chang, C. Earthbound China: A Study of Rural Economy in Yunnan; Routledge: London, UK; Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Edric, H.O.; Kochen, M. Perceived acquaintanceship and interpersonal trust: The cases of Hong Kong and China. Soc. Netw. 1987, 9, 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Miller, J.K. Guanxi dynamics and entrepreneurial firm creation and development in China. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2010, 6, 267–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A.; Starr, J.A. A network model of organization formation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1993, 17, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalet, J. Tripartite guanxi: Resolving kin and non-kin discontinuities in Chinese connections. Theory Soc. 2020, 50, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.W.; Laws, E. Tourism marketing opportunities for Australia in China. J. Vacat. Mark. 2002, 8, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, A.H.M.; Smith, G.M. Reintroducing friendship to international relations: Relational ontologies from China to the West. Int. Relat. Asia Pac. 2018, 18, 369–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.H.M. Worlds beyond Westphalia: Daoist dialectics and the ‘China threat’. Rev. Int. Stud. 2013, 39, 549–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.Q. A relational theory of world politics. Int. Stud. Rev. 2016, 18, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for The Social Sciences, 4th ed.; Alyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Figueredo, P. The role of dual embeddedness in the innovative performance of MNC subsidiaries: Evidence from Brazil. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraris, A.; Santoro, G.; Scuotto, V. Dual relational embeddedness and knowledge transfer in European multinational corporations and subsidiaries. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, P. Structural vs. relational embeddedness: Social capital and managerial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 1129–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzi, B. Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: The paradox of embeddedness. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Welsey: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Collective action and the evolution of social norms. J. Nat. Resour. Policy Res. 2014, 6, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.K. Face and Favor: The Chinese Power Game. Am. J. Sociol. 1987, 92, 944–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, Y.L. The philosophy at the basis of traditional Chinese society. In Selected Philosophical Writings of Fung Yu-lan; Foreign Languages Press: Beijing, China, 1998; pp. 632–639. [Google Scholar]

- Sechrist, G.B.; Young, A.F. The influence of social consensus information on intergroup attitudes: The moderating effects of ingroup identification. J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 151, 674–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, M.J. The Justice Motive in Social Behavior: An Introduction. J. Soc. Issues 1975, 31, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, M.J. The Justice Motive: Some Hypotheses as to Its Origins and Forms. J. Personal. 1977, 45, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, T.; Wu, B.; Guo, L.; Shi, H.; Chen, N.C.; Hall, C.M. Semi-Acquaintance Society in Rural Community-Based Tourism: Case Study of Moon Village, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5000. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065000

Li T, Wu B, Guo L, Shi H, Chen NC, Hall CM. Semi-Acquaintance Society in Rural Community-Based Tourism: Case Study of Moon Village, China. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):5000. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065000

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Taohong, Bo Wu, Ling Guo, Hong Shi, Ning Chris Chen, and C. Michael Hall. 2023. "Semi-Acquaintance Society in Rural Community-Based Tourism: Case Study of Moon Village, China" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 5000. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065000

APA StyleLi, T., Wu, B., Guo, L., Shi, H., Chen, N. C., & Hall, C. M. (2023). Semi-Acquaintance Society in Rural Community-Based Tourism: Case Study of Moon Village, China. Sustainability, 15(6), 5000. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065000

_Chen.png)