Systematic Review of Misinformation in Social and Online Media for the Development of an Analytical Framework for Agri-Food Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What is the current state of the literature on mis-dis-mal-information, including study types, frameworks, actors, focuses, tools, and main conclusions?

- How is mis-dis-mal-information characterized and defined in the literature?

- How can existing studies on mis-dis-mal-information in social and online media be used to draw conclusions and provide recommendations for agri-food advisory communities of practice?

2. Review: Social Media and Online Mis-Dis-Mal-information

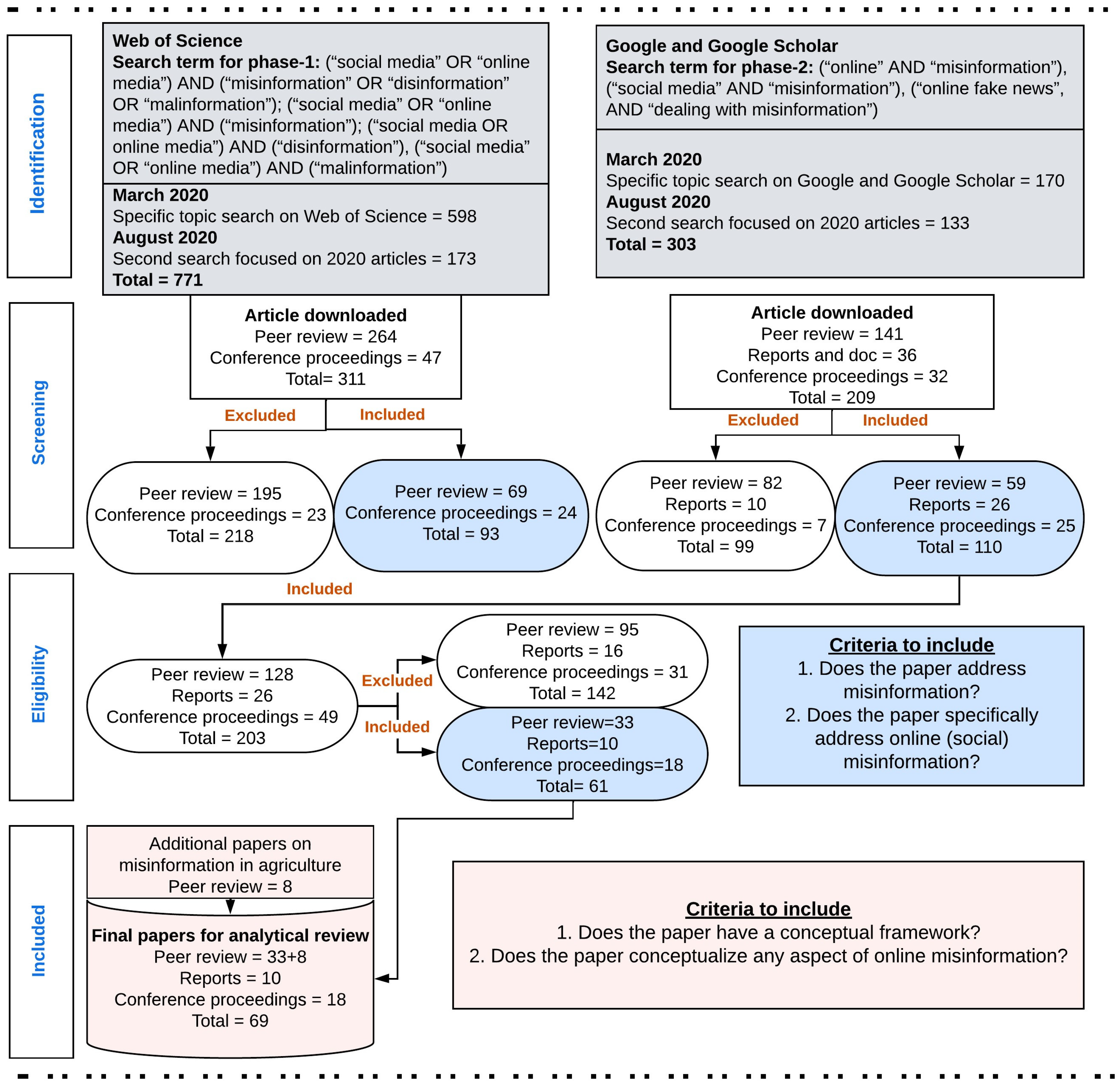

3. Methods

4. Results

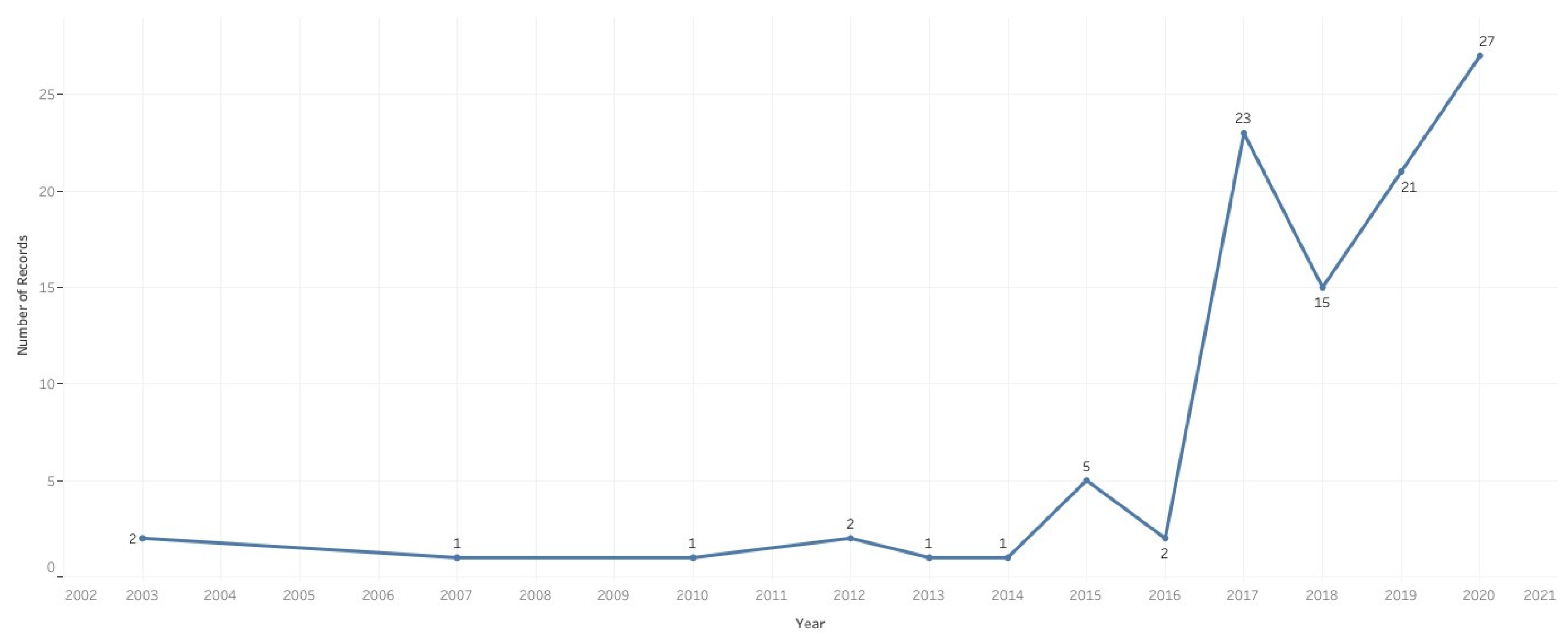

4.1. Temporal Growth of Mis-Dis-Mal-information Research

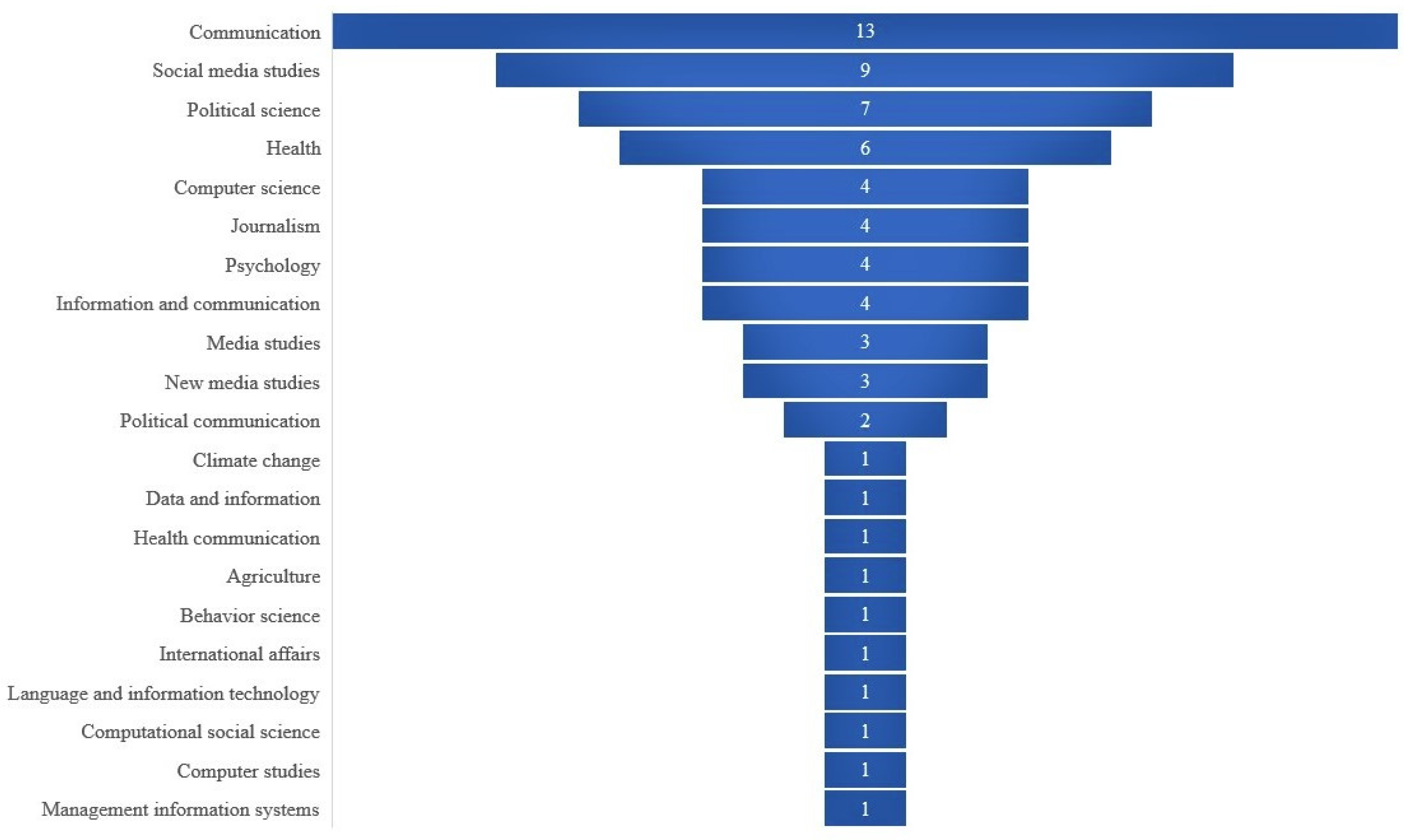

4.2. Main Discipline of Mis-Dis-Mal-information Research

4.3. Major Themes in Conceptual Literature

4.3.1. Theme 1: Characterization and Definition of Mis-Dis-Mal-Information

4.3.2. Theme 2: Sources of Mis-Dis-Mal-Information

4.3.3. Theme 3: Diffusion and Dynamics of Mis-Dis-Mal-Information

4.3.4. Theme 4: Mis-Dis-Mal-information Behaviors

4.3.5. Theme 5: Detection of Mis-Dis-Mal-Information

4.3.6. Theme 6: Strategies for Countering, Correcting, and Dealing with Mis-Dis-Mal-Information

4.4. Zooming in on Agri-Food (Mis-Dis-Mal) Information and Social Media CoPs

4.5. Frameworks for Researching and Understanding Online Mis-Dis-Mal-information

5. A Framework for Researching and Understanding Social Media and Online Agricultural Mis-Dis-Mal-Information

6. Conclusions and Areas for Further Engagement for Research and Development

7. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Editorials Nature. To End Hunger, Science must Change its Focus. Nature 2020, 586, 336. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, K.H.; Hassan, F.; Mukta, M.Z.N.; Roy, D.; Darr, D.; Leggette, H.; Ullah, S.M.A. Application of the Technology Acceptance Model to Assess the Use and Preferences of ICTs among Field-level Extension Officers in Bangladesh. Digit. Geogr. Soc. 2022, 3, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, M.L.; Cofini, F.; Sulaiman, R.V. Agricultural Extension in Transition Worldwide: Policies and Strategies for Reform; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tata, J.S.; McNamara, P.E. Impact of ICT on Agricultural Extension Services Delivery: Evidence from the Catholic Relief Services SMART Skills and Farmbook Project in Kenya. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2018, 24, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwombe, S.O.L.; Mugivane, F.I.; Adolwa, I.S.; Nderitu, J.H. Evaluation of Information and Communication Technology Utilization by Small Holder Banana Farmers in Gatanga District, Kenya. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2014, 20, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S. e-Agriculture Prototype for Knowledge Facilitation among Tribal Farmers of North-East India: Innovations, Impact and Lessons. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2013, 19, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L. Digital and Virtual Spaces as Sites of Extension and Advisory Services Research: Social Media, Gaming, and Digitally Integrated and Augmented Advice. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2021, 27, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; ITU. Status of Digital Agriculture in 47 Sub-Saharan African Countries; FAO: Rome, Italy; ITU: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fielke, S.; Taylor, B.; Jakku, E. Digitalisation of Agricultural Knowledge and Ad-vice Networks: A State-of-the-art Review. Agric. Syst. 2020, 180, 102763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, C.; Ayre, M.; Nettle, R.; Dela, R.B. Making Sense in the Cloud: Farm Advisory Services in a Smart Farming Future. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2019, 90–91, 100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijswijk, K.; Klerkx, L.; Turner, J.A. Digitalisation in the New Zealand Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation System: Initial Understandings and Emerging Organisational Responses to Digital Agriculture. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2019, 90–91, 100313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruzd, A.; Jacobson, J.; Wellman, B.; Mai, P. Understanding Communities in an Age of Social Media: The Good, the Bad, and the Complicated. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2016, 19, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E.; McDermott, R.; Snyder, W. Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge; Harvard Business School Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gow, G.; Chowdhury, A.; Ramjattan, J.; Ganpat, W. Fostering Effective Use of ICT in Agricultural Extension: Participant Responses to an Inaugural Technology Stewardship Training Program in Trinidad. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2020, 26, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S.; Heeks, R.; Huysman, M. Knowledge and Learning in Online Networks in Development: A Social-capital Perspective. Dev. Pract. 2006, 16, 570–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, T.; Aarts, N.; Termeer, C.; Dewulf, A. Social Media as a New Playing Field for the Governance of Agro-food Sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 18, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccarella, C.V.; Wagner, T.F.; Kietzmann, J.H.; McCarthy, I.P. Social Media? It’s Serious! Understanding the Dark Side of Social Media. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Gallegos, N.; Klerkx, L.; Romero-García, L.E.; Martínez-González, E.G.; Aguilar-Ávila, J. Social Network Analysis of Spreading and Exchanging Information on Twitter: The Case of an Agricultural Research and Education Centre in Mexico. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2021, 28, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivers, C.-A.; Bliss, K.; de Boon, A.; Lishman, L.; Schillings, J.; Smith, R.; Rose, D.C. Videos and Podcasts for Delivering Agricultural Extension: Achieving Credibility, Relevance, Legitimacy and Accessibility. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2021, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birke, F.M.; Lemma, M.; Knierim, A. Perceptions towards Information Communication Technologies and Their Use in Agricultural Extension: Case Study from South Wollo, Ethiopia. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2019, 25, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamruzzaman, M.; Chowdhury, A.; van Paassen, A.; Ganpat, W. Extension Agents’ Use and Acceptance of Social Media: The Case of the Department of Agricultural Extension in Bangladesh. J. Int. Agric. Ext. Educ. 2018, 25, 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munthali, N.; van Paassen, A.; Leeuwis, C.; Lie, R.; van Lammeren, R.; Aguilar-Gallegos, N.; Oppong-Mensah, B. Social Media Platforms, Open Communication and Problem Solving in the Back-office of Ghanaian Extension: A Substantive, Structural and Relational Analysis. Agric. Syst. 2021, 190, 103123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.; Hambly, O.H. Social Media for Enhancing Innovation in Agri-food and Rural Development: Current Dynamics in Ontario, Canada. J. Rural. Community Dev. 2013, 8, 97–119. Available online: https://journals.brandonu.ca/ (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- Materia, V.C.; Giarè, F.; Klerkx, L. Increasing Knowledge Flows Between the Agricultural Research and Advisory System in Italy: Combining Virtual and Non-Virtual Interaction in Communities of Practice. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2015, 21, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, P.; Chowdhury, A.; Odame, H.H.; Paassen, A.V. Social Media for Enhancing Stakeholders’ Innovation Networks in Ontario, Canada. J. Agric. Food Inf. 2018, 19, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekumhene, C.; de Vries, J.R.; van Paassen, A.; Schut, M.; MacNaghten, P. Making Smallholder Value Chain Partnerships Inclusive: Exploring Digital Farm Monitoring through Farmer Friendly Smartphone Platforms. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Jian, L.; Driscoll, K.; Bar, F. The Diffusion of Misinformation on Social Media: Temporal Pattern, Message, and Source. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 83, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Gupta, A.; Kauten, C.; Deokar, A.V.; Qin, X. Detecting Fake News for Reducing Misinformation Risks Using Analytics Approaches. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 279, 1036–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cato, S.; McWhirt, A.; Herrera, L. Combating Horticultural Misinformation through Integrated Online Campaigns Using Social Media, Graphics Interchange Format, and Blogs. HortTechnology 2022, 32, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.; Greig, J.; Rampold, S.; Nelson, H.; Stripling, C. Can You Cite that? De-scribing Tennessee Consumers’ Use of GMO Information Channels and Sources. Adv. Agric. Dev. 2022, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, A.; Rumble, J.N.; Lamm, A.J.; Gay, K.D. Discussing Extension Agents’ Role in Moderating Contentious Issue Conversations. J. Hum. Sci. Ext. 2020, 8, 1. Available online: https://www.jhseonline.com/issue/view/111 (accessed on 15 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Wardle, C.; Derakhshan, H. Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy Making. In Council of Europe Report; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2017; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Final Report of the High-Level Expert Group on Fake News and Online Disinformation. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/final-report-high-level-expert-group-fake-news-and-online-disinformation (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Ferreira, C.M.M.; Sosa, J.P.; Lawrence, J.A.; Sestacovschi, C.; Tidd-Johnson, A.; Rasool, M.H.U.; Gadamidi, V.K.; Ozair, S.; Pandav, K.; Cuevas-Lou, C.; et al. The Impact of Misinformation on the COVID-19 Pandemic. AIMS Public Health 2022, 9, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapferer, J.N. A Mass Poisoning Rumor in Europe. Public Opin. Q. 1989, 53, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolchinsky, E.I.; Kutschera, U.; Hossfeld, U.; Levit, G.S. Russia’s New Lysenkoism. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R1037–R1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazer, D.M.J.; Baum, M.A.; Benkler, Y.; Berinsky, A.J.; Greenhill, K.M.; Menczer, F.; Metzger, M.J.; Nyhan, B.; Pennycook, G.; Rothschild, D.; et al. The Science of Fake News. Science 2018, 359, 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Music, J.; Charlebois, S.; Marangoni, A.G.; Ghazani, S.M.; Burgess, J.; Proulx, A.; Somogyi, S.; Patelli, Y. Data Deficits and Transparency: What Led to Canada’s ‘Buttergate’. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 123, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaëlsson, K.; Wolk, A.; Langenskiöld, S.; Basu, S.; Lemming, E.W.; Melhus, H.; Byberg, L. Milk Intake and Risk of Mortality and Fractures in Women and Men: Cohort Studies. BMJ 2014, 349, g6015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapton, S. Three Glasses of Milk a Day Can Lead to Early Death, Warn Scientists. The Telegraph. 28 October 2014. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/health/news/11193329/Three-glasses-of-milk-a-day-can-lead-to-early-death-warn-scientists.html (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Bushra, A.; Zakir, H.M.; Sharmin, S.; Quadir, Q.F.; Rashid, M.H.; Rahman, M.S.; Mallick, S. Human Health Implications of Trace Metal Contamination in Top-soils and Brinjal Fruits Harvested from a Famous Brinjal-producing Area in Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.J. Harmful Substances Found in Brinjal May Increase Cancer Risk: Study. The Business Insider. 27 September 2022. Available online: https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh/harmful-substances-found-brinjal-may-increase-cancer-risk-study-504038 (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Lynas, M.; Adams, J.; Conrow, J. Misinformation in the Media: Global Coverage of GMOs 2019-2021. GM Crops Food 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norwood, F.B.; Oltenacu, P.A.; Calvo-Lorenzo, M.S.; Lancaster, S. Agricultural and Food Controversies: What Everyone Needs to Know; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Somerville, P. Misinformation in Agriculture Contributing to Tech Block. The Weekly Times. 21 February 2019. Available online: https://www.weeklytimesnow.com.au/agribusiness/misinformation-in-agriculturecontributing-to-tech-block/news-story/d9d3066537c06d6c2a31eafc6a2936c4 (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Goerlich, D.; Walker, M.A. Determining Extension’s Role in Controversial Issues: Content, Process, Neither, or Both? J. Ext. 2015, 53, n3. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, L.J.; Knobloch, N.A.; Tucker, M.A.; Hovey, M. Issues-360TM: An Analysis of Transformational Learning in a Controversial Issues Engagement Initiative. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2021, 28, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-H.; Hsieh, K.-J.; Chang, F.-H.; Chen, N.-C. The Customer Citizenship Behaviors of Food Blog Users. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12502–12520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rawi, A. Gatekeeping Fake News Discourses on Mainstream Media Versus Social Media. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2019, 37, 687–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.P.K.; Geethakumari, G. Detecting Misinformation in Online Social Networks using Cognitive Psychology. Hum. Cent. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2014, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R. Nip Misinformation in the Bud. Science 2017, 358, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzimonti, M.; Fernandes, M. Social Media Networks, Fake News, and Polarization; Working Paper 24462; National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER): Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w24462 (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Gupta, A.; Kumaraguru, P. Misinformation in Social Networks: Analyzing Twitter during Crisis Events. In Encyclopedia of Social Network Analysis and Mining; Alhajj, R., Rokne, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, M.; Piccardi, C.; Levy, M.; McRoberts, N.; Lubell, M. Core-periphery or Decentralized? Topological Shifts of Specialized Information on Twitter. Soc. Netw. 2018, 52, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Chao, N.; Ding, J. Rumormongering of Genetically Modified (GM) Food on Chinese Social Network. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz, A.P.; Benham, A.; Edwards, E.; Fractenberg, B.; Gordon-Murnane, L.; Hetherington, C.; Liptak, D.A.; Smith, M.; Thompson, C. Web of Deceit: Misinformation and Manipulation in the Age of Social Media; CyberAge Books: Medford, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Karlova, N.; Fisher, K.E. A Social Diffusion Model of Misinformation and Disinformation for Understanding Human Information Behaviour. Inf. Res. 2013, 18. Available online: http://InformationR.net/ir/18-1/paper573.html (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Rubin, V.L. Disinformation and Misinformation Triangle: A Conceptual Model for “Fake News” Epidemic, Causal Factors and Interventions. J. Doc. 2019, 75, 1013–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohang, A.; Weiss, E. Misinformation: Toward Creating a Prevention Frame-work. Inf. Sci. 2003, 109–115. Available online: https://proceedings.informingscience.org/IS2003Proceedings/docs/025Kooha.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Allcott, H.; Gentzkow, M.; Yu, C. Trends in the Diffusion of Misinformation on Social Media. Res. Politics 2019, 6, 2053168019848554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, L.; Vraga, E.K. In Related News, that Was Wrong: The Correction of Mis-information through Related Stories Functionality in Social Media. J. Commun. 2015, 65, 619–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, E. Bots, Elections, and Social Media: A. Brief Overview. In Disinformation, Misinformation, and Fake News in Social Media: Emerging Research Challenges and Opportunities; Shu, K., Wang, S., Lee, D., Liu, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, E.; Varol, O.; Davis, C.; Menczer, F.; Flammini, A. The Rise of Social Bots. Commun. ACM 2016, 59, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Lewandowsky, S.; Ecker, U.K.H. Neutralizing Misinformation through Inoculation: Exposing Misleading Argumentation Techniques Reduces their Influence. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.D.; Ng, F.; Ho, C.L.W. COVID-19: Emerging Compassion, Courage and Resilience in the Face of Misinformation and Adversity. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 1425–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sin, S.C.J. ‘Misinformation? What of it?’ Motivations and Individual Differences in Misinformation Sharing on Social Media. Proc. Am. Soc. Info. Sci. Technol. 2013, 50, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireton, C.; Posetti, J.; UNESCO. Journalism, ‘Fake News’ and Disinformation: Handbook for Journalism Education and Training. 2018. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0026/002655/265552E.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2022).

- Lu, X.; Vijaykumar, V.; Jin, Y.; Rogerson, D. Think Before You Share: Beliefs and Emotions that Shaped COVID-19 (Mis)information Vetting and Sharing Intentions among WhatsApp Users in the United Kingdom. Telemat. Inform. 2022, 67, 101750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. (Ed.) The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection; Sage: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rafi, M.S. Dialogic Content Analysis of Misinformation about COVID-19 on Social Media in Pakistan. Linguist. Lit. Rev. LLR 2020, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahinkorah, B.O.; Ameyaw, E.K.; Hagan, J.E.J.; Seidu, A.A.; Schack, T. Rising Above Misinformation or Fake News in Africa: Another Strategy to Control COVID-19 Spread. Front. Commun. 2020, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, M. The COVID-19 Infodemic: Mechanism, Impact, and Counter-Measures—A Review of Reviews. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzar, D.W.; Baig, D.Q.A.; Afaq, D.A.; Taheer, D.T.B.; Amar, D.S. Impact of Infodemics on Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Sleep Quality and Depressive Symptoms among Pakistani Social Media Users during Epidemics of COVID-19. Merit Res. J. Med. Med. Sci. 2020, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, D.; Elliott, R.J.R. Defining Misinformation, Disinformation and Malinformation: An Urgent Need for Clarity during the COVID-19 Infodemic. Discuss. Pap. 2020, 20, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kouzy, R.; Jaoude, J.A.; Kraitem, A.; Alam, M.B.E.; Karam, B.; Adib, E.; Zarka, J.; Tra-boulsi, C.; Akl, E.; Baddour, K. Coronavirus Goes Viral: Quantifying the COVID-19 Misinformation Epidemic on Twitter. Cureus 2020, 12, e7255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.; Rainie, L. The Future of Truth and Misinformation Online; PEW Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Acerbi, A. Cognitive Attraction and Online Misinformation. Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, J.L.; Rosenbaum, J.E. “Fake News,” Misinformation, and Political Bias: Teaching News Literacy in the 21st Century. Commun. Teach. 2020, 34, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, L.; Vraga, E.K. See Something, Say Something: Correction of Global Health Misinformation on Social Media. Health Commun. 2018, 33, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.S.; Jones, C.R.; Hall, J.K.; Albarracín, D. Debunking: A Meta-analysis of the Psychological Efficacy of Messages Countering Misinformation. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 28, 1531–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.L.; Idris, I.K. Recognise Misinformation and Verify before Sharing: A Reasoned Action and Information Literacy Perspective. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2019, 38, 1194–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolin, D.B.; Hannak, A.; Weber, I. Political Fact-checking on Twitter: When do Corrections have an Effect? Political Commun. 2018, 35, 196–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laato, S.; Islam, A.K.M.N.; Islam, M.N.; Whelan, E. Why Do People Share Misinformation during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Jang, S.M.; Kim, D.H.; Kenski, K. Perceptions of Mis- or Disinformation Exposure Predict Political Cynicism: Evidence from a Two-wave Survey during the 2018 US Midterm Elections. New Media Soc. 2020, 23, 3105–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egelhofer, J.L.; Lecheler, S. Fake News as a Two-dimensional Phenomenon: A Framework and Research Agenda. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2019, 43, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Wang, S.; Lee, D.; Liu, H. (Eds.) Disinformation, Misinformation, and Fake News in Social Media: Emerging Research Challenges and Opportunities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stray, J. Institutional Counter-disinformation Strategies in a Networked Democracy. In Proceedings of the WWW ’19: Companion Proceedings of the 2019 World Wide Web Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cinelli, M.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Galeazzi, A.; Valensise, C.M.; Brugnoli, E.; Schmidt, A.L.; Zola, P.; Zollo, F.; Scala, A. The COVID-19 Social Media Infodemic. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, R. Fighting the ‘Infodemic’: Legal Responses to COVID-19 Disinformation. Soc. Media + Soc. 2020, 6, 2056305120948190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangcharoensathien, V.; Calleja, N.; Nguyen, T.; Purnat, T.; D’Agostino, M.; Garcia-Saiso, S.; Landry, M.; Rashidian, A.; Hamilton, C.; AbdAllah, A.; et al. Framework for Managing the COVID-19 Infodemic: Methods and Results of an Online, Crowdsourced WHO Technical Consultation. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Ciampaglia, G.L.; Varol, O.; Yang, K.; Flammini, A.; Menczer, F. The Spread of Low-credibility Content by Social Bots. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovchenko, Y.; Hartmann, M.; Adler-Nissen, R. State, Media and Civil Society in the Information Warfare over Ukraine: Citizen Curators of Digital Disinformation. Int. Aff. 2018, 94, 975–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Dong, H.; Wang, J.; Tang, S. Using Deep Learning to Detect Defects in Manufacturing: A Comprehensive Survey and Current Challenges. Materials 2020, 13, 5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vosoughi, S.; Roy, D.; Aral, S. The Spread of True and False News Online. Science 2018, 359, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, C. Lexicon of Lies: Terms for Problematic Information. Data & Society. 2018, Volume 22. Available online: https://datasociety.net/pubs/oh/DataAndSociety_LexiconofLies.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Bradshaw, S.; Howard, P.N. Troops, Trolls and Troublemakers: A Global Inventory of Organized Social Media Manipulation; Oxford Internet Institute: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Guidi, B. An Overview of Blockchain Online Social Media from the Technical Point of View. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerback, T.; Toepfl, F.; Knoepfle, M. The Disconcerting Potential of Online Disinformation: Persuasive Effects of Astroturfing Comments and Three Strategies for Inoculation Against Them. New Media Soc. 2020, 23, 1080–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwick, A.; Lewis, R. Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online. Data and Society. 2017. Available online: https://datasociety.net/output/media-manipulation-and-disinfo-online/ (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Ong, J.C.; Corbanes, J.V.A. Architects of Networked Disinformation: Behind the Scenes of Troll Accounts and Fake News Production in the Philippines. Communication 2018, 74, 1–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessi, A.; Zollo, F.; Del Vicario, M.; Scala, A.; Caldarelli, G.; Quattrociocchi, W. Trend of Narratives in the Age of Misinformation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Ozdaglar, A.; ParandehGheibi, A. Spread of (Mis)information in Social Networks. Games Econ. Behav. 2010, 70, 194–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, S.; Halpern, D.; Katz, J.E.; Miranda, J.P. The Paradox of Participation Versus Misinformation: Social Media, Political Engagement, and the Spread of Misinformation. Digit. J. 2019, 7, 802–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; McPhetres, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.G.; Rand, D.G. Fighting COVID-19 Misinformation on Social Media: Experimental Evidence for a Scalable Accuracy-Nudge Intervention. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowsky, S.; Ecker, U.K.H.; Seifert, C.M.; Schwarz, N.; Cook, J. Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2012, 13, 106–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treen, K.M.; Williams, H.T.P.; O’Neill, S.J. Online Misinformation about Climate Change. WIREs Clim. Change 2020, 11, e665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Shah, N. False Information on Web and Social Media: A Survey. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.08559. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, R.K.; Poulsen, S. Flagging Facebook Falsehoods: Self-identified Humor Warnings Outperform Fact Checker and Peer Warnings. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2019, 24, 240–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trethewey, S.P. Strategies to Combat Medical Misinformation on Social Media. Post Grad. Med. J. 2020, 96, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühler, J.; Murawski, M.; Darvish, M.; Bick, M. Developing a Model to Measure Fake News Detection Literacy of Social Media Users. In Disinformation, Misinformation, and Fake News in Social Media: Emerging Research Challenges and Opportunities; Shu, K., Wang, S., Lee, D., Liu, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.C.; Boczkowski, P.J. The Reception of Fake News: The Interpretations and Practices that Shape the Consumption of Perceived Misinformation. Digit. J. 2019, 7, 870–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, A.E.; Lingeswaran, S. Misinformation Battle Revisited: Counter Strategies from Clinics to Artificial Intelligence. Companion Proc. Web Conf. 2020, 510–519. [Google Scholar]

- Paynter, J.; Luskin-Saxby, S.; Keen, D.; Fordyce, K.; Frost, G.; Imms, C.; Miller, S.; Trembath, D.; Tucker, M.; Ecker, U. Evaluation of a Template for Countering Misinformation-Real-world Autism Treatment Myth Debunking. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vraga, E.K.; Kim, S.C.; Cook, J. Testing Logic-based and Humor-based Corrections for Science, Health, and Political Misinformation on Social Media. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2019, 63, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourghomi, P.; Safieddine, F.; Masri, W.; Dordevic, M. How to Stop Spread of Misinformation on Social Media: Facebook Plans vs. Right-click Authenticate Approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering & MIS (ICEMIS), Monastir, Tunisia, 8–10 May 2017; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommariva, S.; Vamos, C.; Mantzarlis, A.; Đào, L.U.L.; Tyson, D.M. Spreading the (Fake) News: Exploring Health Messages on Social Media and the Implications for Health Professionals using a Case Study. Am. J. Health Educ. 2018, 49, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennen, J.S.; Simon, F.M.; Howard, P.N.; Nielsen, R.K. Types, Sources, and Claims of COVID-19 Misinformation 2020. p. 13. Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/types-sources-and-claims-covid-19-misinformation (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Wang, X.; Song, Y. Viral Misinformation and Echo Chambers: The Diffusion of Rumors about Genetically Modified Organisms on Social Media. Internet Res. 2020, 30, 1547–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielson, L.; Marcus, B.; Boyle, L. Special Feature: Countering Vaccine Misinformation. Am. J. Nurs. 2019, 119, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bran, R.; Tiru, L.; Grosseck, G.; Holotescu, C.; Malita, L. Learning from Each Other—A Bibliometric Review of Research on Information Disorders. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.; Reed, M.; Skaalsveen, K.; Ingram, J.; Bruyn, L.L. The Use of Twitter for Knowledge Exchange on Sustainable Soil Management. Soil Use Manag. 2019, 35, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveau, L.; Soulignac, V. Knowledge Management for Sustainable Agro-systems: Can Analysis Tools Help Us to Understand and Support Agricultural Communities of Practice? Case of the French Lentil Production. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2018, 9, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, M.; Robertson, B. #Farming365-Exploring Farmers’ Social Media Use and the (re)Presentation of Farming Lives. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 87, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreszczyn, S.; Lane, A.; Carr, S. The Role of Networks of Practice and Webs of Influencers on Farmers’ Engagement with and Learning about Agricultural Innovations. J. Rural. Stud. 2010, 26, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eenennaam, A.V. The History and Impact of Misinformation in the Agricultural Sciences. CAS Initiative on Conspiracy, Misinformation, and the Infodemic. 2022. Available online: https://mediaspace.illinois.edu/media/t/1_k0b1s1mh (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Zerbe, N. Feeding the Famine? American Food Aid and the GMO Debate in Southern Africa. Food Policy 2004, 29, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancke, S.; Frank, V.B.; Geert, D.J.; Johan, B.; Marc, V.M. Fatal Attraction: The Intuitive Appeal of GMO Opposition. Trends Plant Sci. 2015, 20, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.S.; Oh, A.; Klein, W.M.P. Addressing Health-related Misinformation on Social Media. JAMA 2018, 320, 2417–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Southwell, B.G.; Thorson, E.A. The Prevalence, Consequence, and Remedy of Misinformation in Mass Media Systems. J. Commun. 2015, 65, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroud, J.L. Tackling Misinformation in Agriculture. bioRxiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.; Stephens, C.; Stripling, C.; Brawner, S.; Loveday, D. The Effect of Social Media on University Students’ Perceptions of the Beef Industry. J. Agric. Educ. 2017, 58, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogha, K.V.; Shah, N.P.; Prajapati, J.B.; Chaudhari, A.R. Biofilm—A Threat to Dairy Industry. Indian J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 67, 459–466. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, A.; Firoze, A. Combatting Online Agriculture Misinformation (OAM): A Perspective from Political Economy of Misinformation. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the Association for International Agricultural and Extension Education, Thessaloniki, Greece, 4–7 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo, L.S.G.; Puska, A.; Pereira, R.; Farrell, T. Pathway to a Human-values Based Approach to Tackle Misinformation Online. In Human-Computer Interaction. Human Values and Quality of Life; Kurosu, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, N.A.; Stankovics, P.; Jarvis, R.M.; Morris-Trainor, Z.; de Vries, J.R.; Ingram, J.; Mills, J.; Glikman, J.A.; Parkinson, J.; Toth, Z.; et al. Have Farmers Had Enough of Experts? Envir. Manag. 2022, 69, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J.; Maye, D.; Bailye, C.; Barnes, A.; Bear, C.; Bell, M.; Cutress, D.; Davies, L.; de Boon, A.; Dinnie, L.; et al. What are the Priority Research Questions for Digital Agriculture? Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Jia, X.; Zhang, W.; Klerkx, L. The Effects of Combined Digital and Human Advisory Services on Reducing Nitrogen Fertilizer Use: Lessons from China’s National Research Programs on Low Carbon Agriculture. I. J. Agri. Sus. 2022, 20, 1136–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuan-Baltazar, J.Y.; Muñoz-Perez, M.J.; Robledo-Vega, C.; Pérez-Zepeda, M.F.; Soto-Vega, E. Misinformation of COVID-19 on the Internet: Infodemiology study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e18444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Major Theme | Some Focus Questions | Distinctive Concepts for Each Theme |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Characteriza-tion and definitions of misinfo |

| Key terms in the field: Fake news: Information (info) with low felicity, in a journalistic or new format, with intention to deceive [86]. It is simple news items that are intentionally and verifiably false [86,87], created in a journalistic form with the intention to misinform and/or employed by actors to disintegrate news sources or content [86]. Rumor: The spread of unverified info that may later turn out to be true or false [55,86]. Misinfo: Incorrect or misleading info disseminated unintentionally [50,59,64,86] without the intention to cause harm [32]. Misinformation can be high-quality info that spreads because of its efficiency [78]. Disinfo: Incorrect or misleading info that is disseminated deliberately [57,86,88] with intention to cause harm [32]. Malinfo: Info based on reality but used to inflict harm on a person, organization, or country [67]. Info disorder: Broader concept used to describe any unusual occurrence in info, involving misinfo, disinfo, malinfo [32,67]. Infodemics: Flow of an abundance of true and false info during a pandemic [89,90,91]. |

| Theme 2: Sources of misinfo |

| Misinfo emanates from behaviors of diverse actors. From a core controlled by individuals, organizations, bots, governments, etc. [92] and spreads within a network. Critical sources of misinfo identified include: The individual as a source of misinfo online: Individuals, citizens, and the general public [93] and resharing info [94,95]. Individuals may be volunteers and paid citizens [96,97]. False news spreads more than the truth because humans, not bots, are more likely to spread it [95]. Bots and spread of misinfo: Partly through unverified social media accounts [76], disseminates misinfo and amplifies false info [95], mostly through automated processes [94,98]. Social bots’ false impression and particular opinion has widespread public support through ‘astroturfing’ [99]. Organizations as a source of misinfo: Political entities and organizations such as partisan websites amplify misinfo [27], sometimes using cyber troops and private contractors [96,97]. Internet trolls, gamegaters, hate groups and ideologues, the manosphere, conspiracy theorists, hyper-partisan news outlets, and politicians circulate misinfo through blogs [100,101,102]. Government entities spread misinfo: Government-sponsored accounts, web pages or applications, and fake accounts spread misinfo for state interests [97]. |

| Theme 3: Diffusion and dynamics of misinfo |

| Identifiable dynamics of misinfo flow: Misinfo is temporary: False rumors (misinfo) tend return multiple times after initial publication, while true rumors (facts) do not. Rumor resurgence continues, often accompanying textual changes, until tension around the target dissolves [27,60]. Speed of diffusion varies: Falsehood diffuses significantly farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than truth [102]. Individuals and misinfo elements diffuse through agents. These signals can partially influence agents directly by not altering fake news or indirectly by following friends who are themselves influenced by bots which can generate misinfo and polarization in the long run [52,97]. “Forceful” agents influence beliefs of (some of) the other individuals they meet but do not change their own opinions [103]. Use accounts, either real, fake, or automated, to interact with users on social media or create substantive content. Valence, a term used to define attractiveness (goodness) or averseness (badness) of a message, event, or thing [97]. |

| Theme 4: Misinfo behaviors |

| Notable misinfo behaviors: Individual behaviors: People’s sharing of misinfo on social media is influenced by individual characteristics [48,65,66,78], including personalities, political interests, social motives, and capacities. Individual personalities can facilitate misinfo. For example, extroverts are more prone to share misinfo for socializing purposes [48,66]; self-expression and socializing motivations are crucial to misinfo sharing [48], and gender could influence misinfo sharing behaviors [48]. People’s political behaviors and interests affect misinfo behaviors. For example, politically enthusiastic people tend to share misinfo [104]; people sometimes deliberately share false content because it furthers their political agenda [65,105], and pre-existing socio-political and cultural beliefs and bias entrench misinfo [103,106,107]. Misinfo and motivations. Top motivations for misinfo sharing are obtaining others’ opinions on that info, expressing their own opinions, and interacting with others [66]; people share info based on its ability to spark conversations [48]; people are more likely to share info by virtue of novelty [95], and misinfo is not always intentional [105]. Individual capacity and capabilities affect misinfo. For example, sharing info on social media without verification is predicted by Internet experience, Internet skills of info seeking, sharing, verification, attitude towards info verification, and belief in the reliability of info [82]. Individual cognitive process [78] involved in the decision to spread info involves consistency of the message, the coherency, the credibility of the source, and general acceptability of the message [50]. Other socio-economic conditions affect misinfo sharing. For example, “self-efficacy to detect misinfo on social media is predicted by income and level of education, Internet skills of info seeking and verification, and attitude towards info verification” [82]. Info behaviors: Misinfo exhibits some characteristics, either familiar or very different from the expected info. Misinfo starts from a core and spreads in a network. Core is controlled by individuals, organizations, bots, or partnerships [92]. Misinfo mutates faster over time [27]. |

| Theme 5: Detection of misinfo |

| Varied strategies for the detection of misinfo: Info literacy and detecting misinfo: Misinfo and disinfo are closely linked to info literacy, especially how they are diffused and shared, and how people use both cues for credibility and deception to make judgments [57,65]. Automated systems can detect misinfo: Automated detection systems or computerized forms of detecting misinfo [108] using algorithms [80,108]. For example, Hoaxy, an open platform that enables large-scale, systematic studies of how misinfo and fact-checking spread [92], and the Fake News Detection (FEND) system [28]. Organizational strategies allow for identifying misinfo: Organizations such as academics or news outlets can provide gate-keeping [49] to detect misinfo. Fact-checking entities contribute to detection [83,109]. |

| Theme 6: Strategies for countering, correcting, and dealing with misinfo |

| Countering and correcting misinfo includes individuals, organizations, governments, and social media outlets. Individuals can play roles in correcting misinfo: Culture of fact-checking by people [110]. People detect misinfo using cues for deception, and info literacy is helpful [82,111]. Individuals who follow and are followed by people can minimize misinfo through gate-keeping info [83]. Individuals are relevant to social corrections, for example, as they effectively limit misperceptions, and correction occurs for high and low conspiracy belief individuals [80]. Reception of misinfo is crucial to prevention: Individual reception can be influenced by traditional fact-based media, accompanied by rejection of opinionated outlets; personal experience and knowledge; repetition of info across outlets; consumption of cross-ideological sources; fact-checking; trust in specific personal contacts [112]. Organizations (academia, media, independent fact-checkers, etc.) [113] could minimize misinfo: Stray categorized tactics used by organizations: refutation, exposure of inauthenticity, alternative narratives [61], algorithmic filter manipulation [80], speech laws, censorship [88]. Strategies include careful dissemination, expert fact-checking, social media campaigns, and greater public engagement by organizations [110] as well as prebunking of people against misinfo, debunking [81,114] messages by organizations, warning of threats reduce misinfo [64,115] and its persistence. Organizations can use an info architect solely responsible for the info and dissemination [59]. States and governments can counter misinfo. Governments can further tackle misinformation through regulations and censorship [113], algorithmic filter manipulation, speech laws, and censorships [88]. For example, the EU East StratCom Task Force, a contemporary government counter-propaganda agency, and China’s info regime are networked info control [88]. Social media networks: Facebook, Twitter, and other networks have made numerous changes to their operations to combat disinfo [88,116], such as automated correction through algorithmic filter manipulation and censorship, facilitated by bots made possible by networks [80,117]. |

| Citation | Key Components | Comment on Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Egelhofer and Lecheler [86] | Focus: Types/forms of fake news; identification of fake news; characterization of info. | Egelhofer and Lecheler [86] offer frameworks for research into fake news allowing researchers to characterize fake news, including in online mediums. The framework can help in the characterization of misinfo in online media. The focus on contents and attribution of info disorder to false content is a notable limitation. This is because accurate content can also be employed to misinform if used incorrectly. |

| Cook et al. [64] | Focus: Dealing with misinfo. | Cook et al. [64] employ two established concepts and apply them to the misinfo literature. The focus is on dealing with misinfo. The strength of their approach is their ability to apply and situate concepts within misinfo. Provides a limited view on dealing with misinfo since recent experiences show it requires more than social strategies to deal with the phenomenon. |

| Ireton et al. [67] | Focus: Elements in misinfo diffusion; characterization of misinfo. | Ireton et al. [67] provide an overview of misinfo in their handwork for a journalist. Frameworks provided in the handbook are essential to how we situate misinfo as a phenomenon and how it relates to journalists’ work. However, the focus on one discipline limits their work, applying a broader interest in misinfo. |

| Ji et al. [55] | Focus: Rumor mongering. | Framework allows us to appreciate misinfo elements which can be considered through different scales of action. |

| Rubin [58] | Focus: Misinfo and disinfo interventions. | Rubin [58] offers a method for dealing with misinfo. Levers of the ‘triangle’ offer practitioners what to focus on as strategies to combat the phenomenon. Framework is useful for researchers to start identifying components and interrogating misinfo. |

| Fard and Lingeswaran [113] | Focus: Strategies for countering misinfo. | Scaler approach to understanding the countering strategies for social media misinfo provides granular scale view of phenomenon. Crucial to understand misinfo elements, but focusing on one component limits its ability to describe misinfo effectively. |

| Piccolo et al. [135] | Focus: Tackling online misinfo. | The human value approach to misinfo countering allows for social view of the phenomena and would be critical to influencing human behaviors that drive misinfo. Approach is limited, as misinfo is increasingly shown to be diffused by non-human actors. |

| Tangcharoensathien et al. [91] | Focus: Managing Infodemic. | Framework is an excellent first step in plausible strategies for managing the contemporary infodemic. The generic focus on all forms (online and offline) may undermine the ability to incorporate the unique challenges of a social media misinfo. |

| Treen et al. [107] | Focus: Understanding the diffusion of climate change misinformation on social media. | Framework is one of first attempts to comprehend interconnected features of online social networks and underlying human and platform factors that may increase social media users’ susceptibility to consume, accept, and propagate misinfo. Framework needs further examination. |

| Wardle and Derakhshan [32] | Focus: Discussing and researching information disorder. | Framework reveals we must comprehend ritualistic function of communication. |

| Major Theme | Potential Questions |

|---|---|

| Characterization and definitions of mis-dis-mal-information |

|

| Sources of mis-dis-mal-information |

|

| Diffusion and dynamics of mis-dis-mal-information |

|

| Detection of mis-dis-mal-information |

|

| Impacts of mis-dis-mal-information |

|

| Strategies for countering, correcting, and dealing with mis-dis-mal-information |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chowdhury, A.; Kabir, K.H.; Abdulai, A.-R.; Alam, M.F. Systematic Review of Misinformation in Social and Online Media for the Development of an Analytical Framework for Agri-Food Sector. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064753

Chowdhury A, Kabir KH, Abdulai A-R, Alam MF. Systematic Review of Misinformation in Social and Online Media for the Development of an Analytical Framework for Agri-Food Sector. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):4753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064753

Chicago/Turabian StyleChowdhury, Ataharul, Khondokar H. Kabir, Abdul-Rahim Abdulai, and Md Firoze Alam. 2023. "Systematic Review of Misinformation in Social and Online Media for the Development of an Analytical Framework for Agri-Food Sector" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 4753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064753

APA StyleChowdhury, A., Kabir, K. H., Abdulai, A.-R., & Alam, M. F. (2023). Systematic Review of Misinformation in Social and Online Media for the Development of an Analytical Framework for Agri-Food Sector. Sustainability, 15(6), 4753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064753