Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic, working from home has unquestionably become one of the most extensively employed techniques to minimize unemployment, keep society operating, and shield the public from the virus. However, the impacts of work-from-home (WFH) on employee productivity and performance is not fully known; studies on the subject are fragmented and in different contexts. The purpose of this study is therefore to provide systematic review on the impact of WFH on employee productivity and performance. A sample of 26 studies out of 112 potential studies (from various databases, including Scopus, Google Scholar, and the Web of Science database from 2020 to 2022) were used after a comprehensive literature search and thorough assessment based on PRISMA-P guidelines. Findings reveal that the impact of the WFH model on employee productivity and performance depend on a host of factors, such as the nature of the work, employer and industry characteristics, and home settings, with a majority reporting a positive impact and few documenting no difference or a negative impact. This study recommends that an improvement in technology and information technology (IT) training and capacity-building would yield more significant results to those who are willing to adopt the WFH model even after the pandemic.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak has changed the world, introducing new social expectations and ways of living [1]. COVID-19 is a deadly transmittable virus. Work-from-home (WFH) has become the new standard due to businesses changing their current operating regime in response to the COVID-19 pandemic [2,3,4,5]. WFH is an employment arrangement in which employees are not required to physically report to a central place of work, such as an office building, warehouse, or retail shop, etc., but instead work from their home or any offsite location (remote work, (RW)) while keeping communication with colleagues and performing duties using telephone, email, and virtual conferences (telework, (TW)). The declaration of a new virus known as COVID-19, also known as the coronavirus, has stunned people all around the globe. According to statistics from [6], this virus spreads quickly and vaccines are limited or nonexistent, thus making it difficult to contain the pandemic, as no safeguards against viral transmission have occurred. In addition, due to difficulties in the economic pace, this has had significant impacts on all aspects of life, including livelihoods and businesses [7,8,9,10,11,12].

According to [13], 59 countries across the globe mandated that public workers who can carry out their job-related tasks and duties remotely must work from home to stop the further spread of the COVID-19 virus ([13]). Due to people’s fear of leaving the house and government orders urging people to stay home to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus, several major retailers and businesses were forced to close temporarily or permanently [7]. Some businesses that had direct contact with customers temporarily shuttered their doors and shifted their attention to Internet trade. For employees who worked from home to serve customers, this shift impacted their work–life balance, either immediately or eventually, due to the changes in formerly consistent activities [7].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, working from home unquestionably became one of the most extensively employed techniques to minimize unemployment, keep society operating, and shield the public from the virus [13]. Work-from-home is working remotely from a nonoffice location, most often at the employee’s residence [7]. It is also commonly referred to as telecommuting. Governments promote, and in some circumstances even demand, personnel who can carry out their work-related obligations and activities from a distant place to lessen the danger of epidemics.

Companies are increasingly enabling their employees to work from home for several reasons, including cheaper office rent costs, improved work–life balance, travel-time savings, and minimizing the spread of the deadly virus [14]. The author also reports that working from home has grown increasingly prevalent during the quarantine phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, as many countries used a physical separation strategy to prevent the spread of the virus. Consequently, working from home is becoming the only choice for some workers. However, according to Gibbs et al. (2021), workers with children living at home lost more outstanding production than those without children, although all employees lost output. In addition, WFH was more harmful to females than males, although this differential was unrelated to the number of children in the family. Instead, it may have resulted from the different domestic obligations women must fulfill when working from home.

Ref. [15] reports that the impacts of WFH on productivity remain unknown. Some experts think teleworking could be suitable for working life [16]. For example, letting employees work from home shows that the company has a human-centered strategic vision, which helps the company support its workers’ mental and physical health. During the COVID-19 crisis, Ref. [17] discovered a beneficial influence on the productivity of call-center staff.

Ref. [18] noted that working from home has many disadvantages, including an absence of supervision, which might lead to arguments. The negative aspects of working from home include the potential for a repetitive and uninspiring work environment and the absence of a clear demarcation between work and leisure time. These drawbacks may increase workplace anxiety, lowering productivity as assessed by the company’s performance metrics. One of the challenges that Ref. [19] identified in their study is that communication, coordination, and cooperation are more expensive in a virtual work context, which is expected to provide a significant barrier to WFH in jobs where such components are vital, particularly for less-experienced employees. Ref. [20] stated that WFH has been demonstrated to be equally advantageous and negatively impacts productivity, depending on abilities, education, tasks, or sector. Reference [20] also reported that physical health moderates WFH’s productivity effect, and muscular issues are frequently mentioned as a concern with WFH.

Working from home (interchangeably referred to as telework or remote work) is not a novel concept, as it had been practiced to some extent in the pre-COVID-19 era. For instance, in the 1970s, remote work was thought to be a means to minimize the heavy reliance on the importation of fuel for transport [21,22], and work arrangement for future telework [23]. Furthermore, some small businesses used part of their home for provision stores (selling simple groceries, among other items) [24]. However, the diffusion of work from home or telework, largely used as an occasional work pattern, had proven slow until 2019, when COVID-19 started and became more severe in the following years. This has fast-tracked the WFH model as the only means for employee and business survival. Unlike the pre-COVID-19 remote-working model, WFH during COVID-19 was associated with emotional disruption and strict, restrictive policies which impacted employee performance and productivity. Academic research on the impacts on productivity due to WFH has not been exhaustive, and thus there is only limited and fragmented academic literature on the subject. In emergency situations, public health workers must utilize WFH fully and mandatorily. Consequently, systematic reviews on WFH will assist us in traversing this fragmented knowledge base. Critically assessing study components, including methodology, research topics, participant data and findings on WFH during COVID-19, and employee productivity will deepen the understanding on its impacts and establish a framework for intervention and future research.

Based on these premises, this paper provides a systematic review on how the remote-work paradigm affected employee productivity and performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. The following research questions will be addressed in this review: Does working from the home influence the productivity and performance of employees? What are the factors influencing productivity for employees working from home? Answering these questions will assist in advancing the area of research, but it is not limited to that. In addition, it will help policymakers, employee unions, employees, and organizations to plan and be aware of the cost and benefits of the work-from-home strategy.

The remaining parts of the research are organized as follows: The method used for the review is discussed in Section 2. The results are presented in Section 3, while the discussions of those results are documented in Section 4. Lastly, the conclusions with recommendations and study limitations are highlighted in Section 5 and Section 6, respectively.

2. Methods

A systematic review of the literature is based on strict, objective standards that promote transparency and allow for replication by other researchers. This section discusses the study-selection approach, the research design inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as the quality of assessment and synthesis.

2.1. Study-Selection Strategy

Using the following online resources, a search strategy was developed to discover pertinent research to provide a solution to the research topic. These resources include Google Scholar, the Scopus and Web of Science databases, as well as Library, Research Gate, Elsevier, and Sage Publication. The search approach was limited to literature published between 2020 and 2022. The search technique was focused on the right combination of specified phrases using Boolean operators, including the essential concepts such as “Impact of Work from Home on employee’s performance”, “Impact of Work from Home on employees productivity”, “WFH on employee productivity”, “remote work”, “Work from home during COVID-19”, “Effects of WFH on the employee”, “teleworking during COVID-19”, “effect of WFH”, “work from home”, and “business productivity”. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, (PRISMA), a set of guidelines, was used to guide the conduct of the systematic review and the reporting of its findings.

The following primary research questions guided the selection of literature: Does work-from-home influence the productivity of employees? What are the factors influencing productivity for employees working from home? Before conducting full-text reviews, the researchers assessed the titles and abstracts of the search results to determine eligibility. To be included, publications must have addressed the effect of WFH during the COVID-19 pandemic on employee productivity and business performance.

The following sections further explain the study design inclusion and exclusion criteria, quality of assessment, and research synthesis.

2.2. Study Design Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

For inclusion in this review, studies were required to focus on answering the research questions of whether the environment of the work-from-home arrangement had any impact on business and employee performance, as well as the outcome, whether the impact was positive or negative. Because the review is solely concerned with assessing literature on WFH in the context of COVID-19, peer-reviewed journal publications published between January 2020 and the present were included. For clarity, the writers included only publications published in English. Studies that focused on the impacts of work-from-home on employee productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic were included, but those studies conducted in the period prior to the COVID-19 pandemic were excluded. This search included quantitative and qualitative studies. The exclusion criteria also included papers not published in English, not related to the subject matter covered, as well as news articles, reports, and dissertations, and publications that did not address the critical questions of this study.

2.3. Quality of Assessment

With respect to the screening procedure, the quality of the studies was assessed in accordance with the PRISMA-P guidelines. The screening technique included investigating each study’s goal and if it addressed any of the research questions. Second, the quality assessment centered on measuring worker performance and productivity. Third, data were extracted on the study characteristics and outcomes. Studies that failed to meet the quality assessment criteria were eliminated. Following the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the researchers examined the adequacy of the titles and abstracts, then assessed the probability of bias and extracted the data.

2.4. Synthesis

The researchers examined the remaining 26 papers using thematic synthesis after the selection procedure. Thematic analysis is well-known for assisting in the extraction of information from the literature in order to synthesize it into an analytical topic. It is appropriate in answering our specific questions.

3. Results

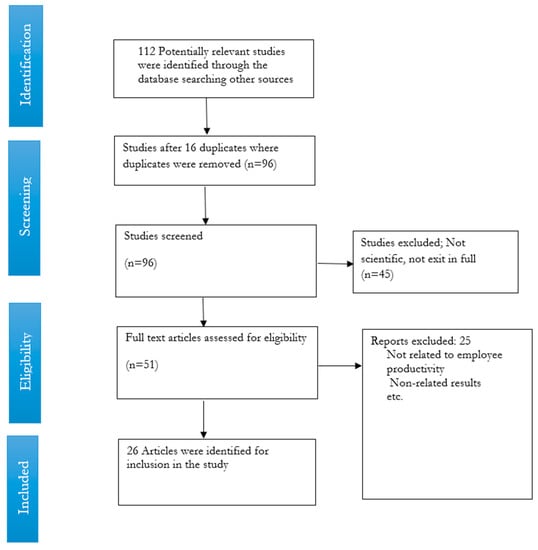

A selection of 26 studies was used in this systematic review and the geographical jurisdiction of these studies was not constrained to a specific place. One hundred and twelve (112) prospective papers were discovered throughout the search; 16 duplicates and 45 titles and abstracts were eliminated as nonscientific. The 51 remaining papers were then assessed according to the eligibility criteria, during which the researchers read through the complete texts and searched for possibly relevant material to the topics under discussion. Twenty-six (26) papers remained after rigorous evaluation on the basis of the criteria used to include or exclude publications. Figure 1 of the PRIMA flow diagram depicts this process in detail.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study search and selection.

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.1.1. Location

Research that has been done on the effects of WFH on worker productivity and performance includes many locations/countries that are frequently connected to various societal norms and individual characteristics. This covers studies in the context of low-, middle-, and high-income countries such as Saudi Arabia, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Poland, Europe, Hungary, Italy, Turkey, Washington, Luxembourg, Germany, and Slovenia. Studies in the context of Africa are greatly limited in the existing literature, arguably because of a lack of infrastructure and a low adoption rate.

3.1.2. Aims of the Study

Studies were carefully chosen for inclusion in the review based on their relevance to the research questions. This includes studies that look at how researchers experience WFH and their productivity and performance outcomes [25], as well as those that examine how attitudes and views and the relationship between requirements and facilities for working from home were influenced by factors such as gender, education level, and job position [26]. Additionally, Ref. [27] conducted a study that sought to ascertain the association between the degree of telecommuting and employee job productivity and work–life balance. Other studies included in this review aimed to better understand employee motivation and demotivation during the COVID-19 pandemic, which affected employee performance on Sayurmoms [28]; investigated the impact of working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic on job engagement [29]); examined how attitudes and views and the relationship between requirements and facilities for working from home were influenced by factors such as gender, education level, and job position [26]; attempted to learn more about how University of Ljubljana students and staff behaved toward WFH and online learning [30]; investigated how employee productivity related to work-from-home (WFH) practices during the COVID-19 pandemic (Farooq and Sultana, 2021), how the remote working system affected millennial employee performance during the COVID-19 pandemic [31], and the impact of WLB, work happiness, and mental health on employee productivity in the Greater Jakarta area’s banking businesses [32].

Some studies examined the impact of the WFH (work-from-home) system’s implementation on worker output in the Medan City Office [33]; investigated and illustrated how organizational culture, WFH, and dedication to WFH affected employee performance [34]; investigated how employees’ home-based work habits affected both individual and group productivity [35]; investigated the relationship between the usage of digital technologies for cooperation and communication and the rise in the subjective well-being of teleworkers (job happiness, job stress, and job productivity) both during and prior to the first lockdown in spring 2020 [36]; examined the impact of successful work-from-home leadership, competency, training, and technology on employee performance in the manufacturing sector [37]; investigated the direct effects of WFH on productivity, as well as the mediating effects of WFH on productivity [38,39]; investigated how work-from-home policies affected Filipino employee productivity [40]; investigated how working from home affected employee performance [41]; looked into how WFH affected employee output (Shi et al., 2020); determined whether employee participation in remote work arrangements was associated with perceived overall job performance and remote work productivity [42]; investigated the unusual and unique challenges of negotiating the work–nonwork interface and how employees are better prepared to deal with the work-from-home trial [43].

3.2. Study Methodology

3.2.1. Study Sample

Depending on the target participants, research location, methodology, and the goal of the study, different sample sizes have been employed in the literature. As a result, there is no uniformity in terms of sample size in the literature. The most extensive research sample size included 11011 workers, which was a study conducted in Europe [35], followed by 2174 employees from Washington [44]. Pokojski’s study included 248 Polish commercial firms, 1300 participants each in Slovenia and Europe [30], and 1200 and 50 participants, respectively, in Indonesia [39,41], all conducted across different industries and institutions.

3.2.2. Nature of the Study and Design

The available research on the influence of WFH on employee productivity and business performance is mostly a composite of qualitative studies, such as [26,27,28,32,39], quantitative studies [31,33,45], and mixed methods studies [46] using survey designs [33].

3.3. Findings

Table 1 summarizes studies on the impact of WFH on employee productivity that have passed through the quality assessment criteria. The results of the study are presented for each of the subjects of the study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

Ref. [52] looked into the impact of telework on work productivity in Indonesia, surveying 330 employees, and concluded that the employees reported more satisfaction, contentment, and motivation when they worked from home, which boosted job performance. Reference [53] investigated the effect of WFH on organizational commitment the institution’s culture and on job satisfaction in 105 Kupang employees. According to the findings [53], WFH, organizational commitment, and organizational culture all had a favorable and significant effect on employee performance, either partially or concurrently.

Ref. [49] conducted interviews with 24 middle and senior managers in India to study the impact of work-from-home on workers in India’s industrial and business sectors, made possible by advances in information technology. Workers proclaimed longer work hours, significant changes in duties, reduced productivity, and more stress. Ref. [25] conducted research with 704 academics regarding the researchers’ experiences with WFH in Hong Kong. They found that more than a quarter of the researchers were more productive during the shutdown due to the outbreak than they had been previously. Seventy percent (70%) of researchers said they would be just as productive if they could do some of their work from home at least a portion of the time.

Ref. [35] evaluated the impact on 11,011 European workers who worked from home on individual and team performance. They discovered that working from home may be helpful for some employees, but also has disadvantages. Having a home-based office has been shown to be detrimental to productivity. Furthermore, team performance declines when more teammates work from home. Ref. [30] collected 1300 responses from students and workers at Slovenia’s University of Ljubljana concerning their perceptions of WFH and distance learning in general. There are three main issues that are brought up by respondents: increased stress, decreased study/work efficiency, and a less-than-ideal setting in which to get work done.

In their research, Ref. [26] investigated the role that employees’ perspectives and beliefs played as a “mediating” factor between remote employment and improved productivity in the workplace (WFH). They also looked at the beliefs and perspectives of 399 Saudi workers and how factors such as gender, education, and employment status affected the correlation between remote work needs and available resources. Through examining the attitudes and perspectives of WFH workers as a mediator, the researchers found a robust direct association between WFH and job performance. The study also revealed a strong correlation between WFH and work performance, as well as between the characteristics of WFH individuals and their productivity on the job. Ref. [51] investigated the effect of WFH on the productivity of small, medium, and large businesses in Poland during the pandemic in 234 firms. The performance, control, and support of remote work were all favorably influenced by an organization’s attitude toward it, with the last of these variables having the most impact. The attitude of an organization toward remote work was the most crucial element affecting its support for working remotely outside of the business office [51].

In order to learn how much telecommuting affected workers’ job productivity and work–life balance, Ref. [27] interviewed 396 workers from three business-process-outsourcing (BPO) businesses in the Philippines. Additionally, the author was interested in comparing office workers versus remote workers to see whether there was a discernible difference in output. Results from the study by Ref. [27] show that the amount of time spent telecommuting had no impact on the amount of work completed by remote workers. This conclusion is supported by the fact that there is no statistically significant distinction between how much time is spent on a project at home and in the office and the quantity of work done at each location. According to Ref. [44], as compared to their former employment, 23.8% of respondents reported higher job performance, 36% reported no change, and 38.6 % reported worse productivity. Analyzing disparities in managers’ working circumstances in Turkey involving 211 hotel employees, Ref. [29] demonstrated that working from home has both beneficial and harmful consequences.

In their analysis on the COVID-19 pandemic in India, Ref. [47] examined WFH and employee productivity among 250 respondents. Additionally, they investigated the role that gender plays in the connection between WFH and productivity on the job. Their findings confirm the adverse connection between WFH and employee productivity. According to the study, gender has a role in mediating the connection between WFH and worker output. Hafsah (2022) used 367 answers to investigate how millennial workers fared during the COVID-19 outbreak in Indonesia, where working from home positively affected productivity, morale, and participation in the workplace.

Ref. [50] investigated the impact of COVID-19 on job performance with a sample of 106 employees using technologies to moderate this effect. Working from home enhanced workers’ output quality and performance. Ref. [42] studied 171 participants in Italy to examine if employee engagement in work-from-home arrangements was associated with overall job performance and remote work productivity, and its impacts on the productivity of workers who have children under the age of 18. They concluded that working from home increases one’s sense of productivity, which in turn increases one’s actual productivity. The effects of work–family harmony (WFH) on productivity in the banking industry were studied by Ref. [38] on 234 respondents in Indonesia. They looked at both the direct effect of WFH on productivity and the mediating effect of WFH on productivity via work–life balance and job performance. The authors found that work–family harmony positively affected overall productivity via job satisfaction. However, the results also showed that WFH negatively impacted WLB.

Ref. [41] surveyed 1200 people in Indonesia to assess the impact of telecommuting on productivity. According to the data, employees performed less effectively when working from home, which affected their performance. Ref. [48] looked at the effects of telecommuting, followership style, and work motivation as mediators on the productivity of 142 Indonesian workers. The authors found that working from home had a beneficial but not statistically significant influence on employee performance. Furthermore, Ref. [46] studied the effect of WFH during the lockdown on IT personnel productivity in India, emphasizing organizational difficulties. The authors found that about two-thirds of IT workers said they were more productive at WFH, using the time they saved on commuting to their full advantage to meet rising demands.

According to research conducted by Ref. [40], work-from-home has a detrimental effect on performance. However, work-from-home features have a significant beneficial impact on employee happiness and productivity rather than on workplace stress. The 2020 study by Toriana and Yoesoef investigated the impact of using the WFH method on employee performance in the Medan City Office in Indonesia. The findings of Ref. [33] demonstrated that the work-from-home strategy used in the City of Medan Office was less beneficial in boosting employee performance. Ref. [32] investigated the impact of WLB, job satisfaction, and mental health on employee productivity on WFH in the financial sector of Greater Jakarta in 314 banking workers. The study concluded that job satisfaction and mental health had a positive impact on the productivity of banking employees who adopted the WFH model.

4. Discussion

WFH was recommended as a public health safety precaution throughout the COVID-19 crisis to break the chain of COVID-19 transmission after discovering that overcrowding (in workplaces) might be a risk factor for COVID-19 transmission. WFH may have implications on employee performance and productivity (output per unit input, efficiency, and effectiveness). The productivity of workers is an essential component of any organization that operates, regardless of whether the organization is a public, commercial, or private entity, or whether it is a profit or nonprofit organization.

The findings show that WFH may result in both positive and negative job outcomes on a host of factors such as the nature of work, employers and industry characteristics, and home settings, with a majority reporting a positive impact, while few documented no difference or a negative impact. For instance, in their study, Ref. [25] found that academic researchers in a tertiary institution were more productive with the WFH model than working in an office. Additionally, the authors documented that about 70% out of the 704 researchers believed they would be equally or more productive in the future if they could spend more time working from home. At the workplace, they are better at collaborating with colleagues on projects, communicating with their team, and collecting data, but at home, they were better at working on their manuscripts, reading the literature, and analyzing their data, with a better publication rate. Thus, the nature of work (such as whether work needs collaboration or not) plays a great role on the performance and productivity of employees. Consequently, employees are more productive with WFH given work that does not require collaboration with others, but less productive with work that requires collaboration. This finding is confirmed by Ref. [54], who reported that productivity results from a combination of internal performance behaviors, the macroenvironment, and resource access.

Personal characteristics, such as living with dependents and gender, have also been associated with outcomes with work-from-home. For instance, according to Ref. [42], there is a reported moderating role when living with minor or dependent children. In addition, regardless of the pandemic lockdown, researchers who have children who are reliant on them may benefit less than those researchers who do not have childcare responsibilities [25]. It is important to note that childcare responsibility is one of the primary causes of individuals feeling overwhelmed with their workloads, and, as a consequence, experiencing work–family conflict. The results suggest that human resource professionals need to design support policies that take into consideration the specific characteristics of their employees. There is a correlation between the work–life balance and the gender imbalance, since women are more likely to dedicate themselves to household chores than their male counterpart, thus affecting their productivity and job satisfaction. Studies by Refs. [42,47,55] have identified that gender roles have an impact on employee productivity. The results of the study by Ref. [47] showed that employee productivity in WFH arrangements affected women more than men. Telework is advantageous to women since it makes domestic work and family responsibilities simpler for them than for males. On the other hand, Ref. [42] documented that productivity correlates favorably with perceived remote work productivity regardless of gender. The difference can be attributed to whether or not female workers have additional responsibilities, such as having dependent children, which may negatively affect their productivity due to time competition. Ref. [13] finds it disturbing that the bulk of the repercussions of the pandemic, both economic and societal, is borne by women; they lose their employment, have their hours shortened, and are saddled with a substantial degree of domestic responsibilities. This might reverse the gender equality established prior by the G20 [13].

Ref. [56] argues that an employee’s productivity is a function of both the number of hours he or she spends at the office and the quality of those hours, defined as “mental presence” or effective operation. Findings by Ref. [42] (2021) showed a highly significant direct relationship between overall job performance and RW productivity, showing that people’s views of their productivity generally correspond with the efficiency they portray, even when faced with a substantial change in their work atmosphere, such as the transition to telework due to the COVID-19 outbreak. The results also show that the perception of being a high-performing employee was tied to engagement with the new style of working, which was linked to the experience of being productive even under the new work configuration. According to Ref. [38], job satisfaction is a mediating factor between work–life balance and productivity, and WFH boosts overall productivity. According Ref. [32], WFH, which began as a novel and demanding work arrangement, particularly among employees in the Indonesian banking industry, was shown to increase productivity. WFH encouraged delegating greater responsibility to employees, resulting in more job satisfaction, which led to higher productivity. Ref. [32] suggest that, in order to boost employee productivity under the existing WFH setup, managers and directors should focus on fostering employee job happiness while also fostering mental health awareness in the workplace.

It is often believed that telecommuting offers more convenience than traditional office work, since the working environment plays several significant roles in the employee’s productivity and performance. Ref. [41] documented that telecommuting has a negative impact on productivity. The work environment, technical infrastructure, and intrinsic motivation all have an impact on employee performance when working from home. Meanwhile, no significant relationship was seen between job autonomy and employee performance. Employees have more freedom to work on their responsibilities during their own productive time, unlike in the office. However, there are some challenges regarding the work-from-home environment. Some workers are hampered at their home offices by a lack of Internet and other technological resources that are necessary to do their jobs properly [57]. The government must make an effort to address the issue of inadequate employee work equipment, one of which is the implementation of a work digitalization system. Another measure that leaders should take is to increase the capacity to use technology by offering IT training.

According Ref. [40], factors related to working from home have a significant positive effect on employee satisfaction and output but no impact on occupational stress. Ref. [49] found that there was an increase in the levels of stress on workers as well as reduced productivity. According to research by Ref. [7], employees who can work from home save money on transportation costs, which may lead to less stress and improved performance on the job.

In addition, the nature of work-from-home settings may also have significant impacts on employee productivity. Working from home cannot be generally accepted because there are certain works that cannot be performed from home [39]. For instance, some work requires heavy infrastructure that, in turn, requires a large space for set up and operation, and thus may be difficult to install in the home. Similarly, some onsite jobs, that is, a job that requires employees to visit the site or location of their clients, cannot be performed at home. This may have a negative impact on the productivity of the employees. This finding is consistent with that of Ref. [39], who concluded that WFH is beneficial for some workers but detrimental to others, and that it is the cause for the decline in employee productivity. The authors documented that, while many workers experienced improved work–life balance, WFH cannot be widely embraced, since certain types of work cannot be done in the comfort of one’s own home [40,58].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this research provides a rapid systematic literature review on the effect of WFH on employee productivity and performance based on PRISMA-P guidelines. The findings reveal that the impact of the WFH model on employee productivity and performance depends on a host of factors, such as the nature of work, employer and industry characteristics, and home settings, with the majority reporting a positive impact and few documenting no difference or a negative impact. This has implications on the work model; characteristics such as the nature of the work (researchers at university are more productive with the WFH model, while lecturers and teachers are less productive because the former has less or no direct involvement with people), the position of the employees (directors, managers, or supervisors have increased productivity with WFH because they are able to convert physical mobility to reach out virtually to supervise more tasks and pay attention to details, while lower-rank employees are less productive), the nature of employee tasks (employees performing collaborative task are less productive with WFH), home capacity to use the Internet and technological resources (higher productivity in technologically favorable homes), the nature of the industry (IT and banking and service industries are more productive), gender (female employees are less productive than male counterparts), employee experience (experienced employees are more productive), and the knowledge of IT (IT-literate employees had a positive impact on productivity with WFH).

This study recommends that an improvement in technology and IT training, capacity-building in areas such as virtual teamwork, remote engagement with clients, and support systems for the disadvantaged would yield more significant results to those who are willing to adopt the WFH method even after the pandemic.

6. Limitations and Future Research

This study has a few limitations. First, despite the fact that we completed a thorough search of the published literature, we did not manually search any journals or other sources of gray literature. On the other hand, given that we focused our investigation only in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, we did not believe that any pertinent information would be missed by our computerized searches. Lastly, this review included some studies that were survey-based, online, and cross-sectional. Each of these research methods has their advantages and disadvantages. For example, there may be differences in access to online surveys due to language barriers, and, as a result, the results may not be entirely generalizable to the entire population. However, the research adheres to all of the standard procedures, which helps to guarantee that the data and, more importantly, the conclusion can be replicated.

Various suggestions might be taken into account for future studies. Researchers should also look into whether the implementation of work-from-home has any implications on workers’ income. There still needs to be more literature from Africa regarding this field of study in a developing continent, and research about work-from-home environments and IT tools would benefit governments and policymakers.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (grant number: 121890) and Nelson Mandela University through Vice Chancellor funds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ratten, V. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and entrepreneurship: Changing life and work landscape. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2020, 32, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anakpo, G.; Mishi, S. Business response to COVID-19 impact: Effectiveness analysis in South Africa. The Southern African. J. Entrep. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniffin, K.M.; Narayanan, J.A.F.; Antonakis, J.; Ashford, S.P.; Bakker, A.B.; Vugt, M.V. COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anakpo, G.; Mishi, S. Hesitancy of COVID-19 vaccines: Rapid systematic review of the measurement, predictors, and preventive strategies. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2074716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gqoboka, H.; Anakpo, G.; Mishi, S. Challenges Facing ICT Use during COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Small, Medium and Micro Enterprises in South Africa. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2022, 12, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Organization World, COVID-19 Situation Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Putri, A.; Amran, A. Employees Work-Life Balance Reviewed from Work from Home Aspect During COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2021, 1, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafta, K.; Anakpo, G.; Syden, M. Income and poverty implications of COVID-19 pandemic and coping strategies: The case of South Africa. Afr. Agenda 2022, 19, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Komanisi, E.; Anakpo, G.; Syden, M. Vulnerability to COVID-19 impacts in South Africa: Analysis of the socio-economic characteristics. Afr. Agenda 2022, 19, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Tshabalala, N.; Anakpo, G.; Mishi, S. Ex ante vs ex post asset-inequalities, internet of things, and COVID-19 implications in South Africa. Afr. Agenda 2022, 18, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Anakpo, G.; Nkungwana, S.; Mishi, S. Impact of COVID-19 on school attendance in South Africa. Analysis of sociodemographic characteristics of learners. Helioyn 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Anakpo, G.; Hlungwane, F.; Mishi, S. The Impact of COVID-19 And Related Policy Measures on The Livelihood Strategies in Rural South Africa. Afr. Agenda 2023. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organisation. COVID-19 and the World of Work: Country Policy Responses; International Labour Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thorstensson, E. The Influence of Working from Home on Employees’ Productivity: Comparative Document Analysis between the Years 2000 and 2019–2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1446903/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Productivity Gains from Teleworking in the Post COVID-19 Era: How Can Public Policies Make It Happen? OECD Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Djeebet, H. What Is the Impact of COVID-19 on the Global Hospitality. 2020. Available online: https://www.hospitalitynet.org/opinion/4098062 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Emanuel, N.; Harrington, E. Working Remotely? Working Paper; Department of Economics, Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Madell, R. Pros and Cons of Working From Home. 2019. Available online: https://money.usnews.com/money/blogs/outside-voices-careers/articles/pros-and-cons-ofworking-from-home (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Gibbs, M.; Mengel, F.; Siemroth, C. Work from Home & Productivity: Evidence from Personnel & Analytics Data on IT Professionals. University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No. 2021-56; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa, R.; Kuroda, S.; Okudaira, H.; Owan, H. Working from home and productivity under the COVID-19 pandemic: Using survey data of four manufacturing firms. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e026176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athanasiadou, C.; Theriou, G. Telework: Systematic literature review and future research agenda. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddon, L.; Brynin, M. The character of telework and the characteristics of teleworkers. New Technol. Work. Employ. 2005, 20, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, A.; Illegems, V.; S’Jegers, R. The organisational context of teleworking implementatio. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2001, 67, 275–291. [Google Scholar]

- Vrchota, J.; Maříková, M.; Řehoř, P. Teleworking in SMEs before the onset of coronavirus infection in the Czech Republic. Manag. J. Contemp. Manag. Issues 2020, 25, 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Aczel, B.; Kovacs, M.; Van Der Lippe, T.; Szaszi, B. Researchers working from home: Benefits and challenges. PloS ONE 2021, 16, e0249127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choukir, J.; Alqahtani, M.S.; Khalil, E.; Mohamed, E. Effects of Working from Home on Job Performance: Empirical Evidence in the Saudi Context during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfanza, M.T. Telecommuting Intensity in the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic: Job Performance and Work-Life Balance. Econ. Bus. 2021, 35, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisah, C.; Wisesa, A. The impact of COVID-19 towards employee motivation and demotivation influence employee performance: A study of Sayurmoms. Eqien-J. Ekon. Dan Bisnis 2021, 8, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran-Chi, V.L.; Ly, T.T.; Luu-Thi, H.T.; Huynh, V.S.; Nguyen-Thi, M.T. The Influence of COVID-19 Stress and Self-Concealment on Professional Help-Seeking Attitudes: A Cross-Sectional Study of University Students. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drašler, V.; Bertoncelj, J.; Korošec, M.; Pajk Žontar, T.; Poklar Ulrih, N.; Cigić, B. Difference in the attitude of students and employees of the University of Ljubljana towards work from home and online education: Lessons from COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafshah, R.N.; Najmaei, M.; Mansori, S.; Fuchs, O. The Impact of Remote Work During COVID-19 Pandemic on Millennial Employee Performance: Evidence from the Indonesian Banking Industry. J. Insur. Financ. Manag. 2022, 7, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Heryanto, C.; Nurfauzi, N.F.; Tanjung, S.B.; Prasetyaningtyas, S.W. The Effect of Work from Home on Employee Productivity in The Banking Industry. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 4970–4987. [Google Scholar]

- Imsar, I.; Tariani, N.; Yoesoef, Y.M. The Effectiveness of WFH Work System Implementation on Employee Performance in Dinas Pendidikan, Medan City. J. Manag. Bus. Innov. 2020, 2, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Riwu Kore, J.R.; Zamzam, F.; Haba Ora, F. Iklim Organisasi Pada Manajemen SDM (Dimensi dan Indikator Untuk Penelitian); Deepublish Press: Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Lippe, T.; Lippényi, Z. Co-workers working from home and individual and team performance. New Technol. Work. Employ. 2020, 35, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Hauret, L.; Fuhrer, C. Digitally transformed home office impacts on job satisfaction, job stress and job productivity. COVID-19 findings. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mon, M.D. The effectiveness of work from home (wfh) against employee performance. KINERJA 2021, 18, 397–403. [Google Scholar]

- Prasetyaningtyas, S.W.; Heryanto, C.; Nurfauzi, N.F.; Tanjung, S.B. The effect of work from home on employee productivity in banking industry. J. Apl. Manaj. 2021, 19, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustajab, D.; Bauw, A.; Rasyid, A.; Irawan, A.; Akbar, M.A.; Hamid, M.A. Working from home phenomenon as an effort to prevent COVID-19 attacks and its impacts on work productivity. TIJAB (Int. J. Appl. Bus.) 2020, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauline Ramos, J.; Tri Prasetyo, Y. The impact of work-home arrangement on the productivity of employees during COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines: A structural equation modelling approach. In Proceedings of the 2020 The 6th International Conference on Industrial and Business Engineer, Macao, China, 27–29 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rosidah, S.; Maarif, M.S.; Sukmawati, A. The Effectiveness of Employee Performance of Ministry of Religious Affairs during Work from Home and The Factors that Influence It. J. Manaj. 2022, 13, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, F.; Zappalà, S. Overall job performance, remote work engagement, living with children, and remote work productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Psychol. Open 2021, 80, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troll, E.S.; Venz, L.; Weitzenegger, F.; Loschelder, D.D. Working from home during the COVID-19 crisis: How self-control strategies elucidate employees’ job performance. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 71, 853–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Moudon, A.V.; Lee, B.H.; Shen, Q.; Ban, X.J. Factors influencing teleworking productivity–A natural experiment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riwukore, J.R.; Alie, J.; Hattu, S.V.A.P. Employee performance based on contribution of WFH, organizational commitment, and organizational culture at Bagian Umum Sekretariat Daerah Pemerintah Kota Kupang. Ekombis Rev. J. Ilm. Ekon. Dan Bisnis 2022, 10, 1217–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patanjali, S.; Bhatta, N.M.K. Work from home during the pandemic: The impact of organizational factors on the productivity of employees in the IT industry. Vision 2022, 09722629221074137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, R.; Sultana, A. The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on work from home and employee productivity. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2022, 26, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultom, F.; Wanasida, A. The Effect of Work from Home and Followership Style on Employee Performance Mediating by Work Motivation (A Case Study of PT. Sampang PSC at Post Acquisition). Bp. Int. Res. Crit. Inst. J. 2022, 5, 21731–21743. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, A.; Arun, C.J. Working from home during COVID-19 and its impact on Indian employees’ stress and creativity. Asian Bus. Manag. 2022, 14, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanamurthy, G.; Tortorella, G. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on employee performance–moderating role of industry 4.0 base technologies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 234, 108075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokojski, Z.; Kister, A.; Lipowski, M. Remote work efficiency from the employers’ perspective—What’s next? Sustainability 2022, 14, 4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susilo, D. Revealing the effect of work-from-home on job performance during the COVID-19 crisis: Empirical evidence from Indonesia. J. Contemp. Issues Bus. Gov. 2020, 26, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Marnisah, L.; Kore, J.R.R.; Ora, F.H. Employee Performance Based on Competency, Career Development, And Organizational Culture. J. Apl. Manaj. 2022, 20, 632–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Gerlowski, D.; Acs, Z. Working from home: Small business performance and the COVID-19 pandemic. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 58, 611–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petcu, M.A.; Sobolevschi-David, M.I.; Crețu, R.F.; Curea, S.C.; Hristea, A.M.; Oancea-Negescu, M.D.; Tutui, D. Telework: A Social and Emotional Perspective of the Impact on Employees’ Wellbeing in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanyama, K.W.; Mutsotso, S.N. Relationship between capacity building and employee productivity on performance of commercial banks in Kenya. Afr. J. Hist. Cult. 2010, 2, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar, V.; Bhattacharya, S. Significant household factors that influence an IT employees’ job effectiveness while on work from home. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2021, 13, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alifuddin, N.A.; Ibrahim, D. Studies on the impact of work from home during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic literature review. J. Komun. Borneo 2021, 9, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).