Knowledge and Attitude toward End-of-Life Care of Nursing Students after Completing the Multi-Methods Teaching and Learning Palliative Care Nursing Course

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sampling and Participation

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Outcome and Measurement

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristic of Participant

3.2. Knowledge and Attitudes toward EoLC after the PCN Course with Multi-Methods Learning

3.3. ANOVA Test of Characteristics toward Knowledge and Attitudes

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. The Implication to Clinical Practice

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Zahran, Z.; Hamdan, K.M.; Hamdan-Mansour, A.M.; Allari, R.S.; Alzayyat, A.A.; Shaheen, A.M. Nursing Students’ Attitudes towards Death and Caring for Dying Patients. Nurs. Open 2022, 9, 614–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A’la, M.Z.; Setioputro, B.; Kurniawan, D.E. Nursing Students’ Attitudes towards Caring for Dying Patients. Nurse Media J. Nurs. 2018, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, P.C.; van der Riet, P.J.; Jeong, S. End of Life Care Education, Past and Present: A Review of the Literature. Nurse Educ. Today 2014, 34, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndtsson, I.E.K.; Karlsson, M.G.; Rejnö, Å.C.U. Nursing Students’ Attitudes toward Care of Dying Patients: A Pre- and Post-Palliative Course Study. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubb, C.; Arthur, A. Student Nurses’ Experience of and Attitudes towards Care of the Dying: A Cross-Sectional Study. Palliat. Med. 2016, 30, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broom, A.; Kirby, E.; Good, P.; Wootton, J.; Yates, P.; Hardy, J. Negotiating Futility, Managing Emotions: Nursing the Transition to Palliative Care. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Shan, B.; Zheng, J.; Peng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Miao, X.; Hu, X. Knowledge and Attitudes toward End-of-Life Care among Community Health Care Providers and Its Influencing Factors in China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Medicine 2019, 98, e17683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwawi, A.A.; Abu-Odah, H.; Bayuo, J. Palliative Care Knowledge and Attitudes towards End-of-Life Care among Undergraduate Nursing Students at Al-Quds University: Implications for Palestinian Education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffers, S. Nurse Faculty Perceptions of End-of-Life Education in the Clinical Setting: A Phenomenological Perspective. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2014, 14, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wu, C.; Bai, D.; Chen, H.; Cai, M.; Gao, J.; Hou, C. A Meta-Analysis of Nursing Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes about End-of-Life Care. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 119, 105570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komariah, M.; Maulana, S.; Platini, H.; Pahria, T. A Scoping Review of Telenursing’s Potential as a Nursing Care Delivery Model in Lung Cancer During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 3083–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, M.M.; McDonald, B.; McGuinness, J. The Palliative Care Quiz for Nursing (PCQN): The Development of an Instrument to Measure Nurses’ Knowledge of Palliative Care. J. Adv. Nurs. 1996, 23, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frommelt, K.H.M. Attitudes toward Care of the Terminally Ill: An Educational Intervention. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2003, 20, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project. Jamovi. (Version 2.2) [Computer Software]. Available online: www.jamovi.org (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Schroeder, K.; Lorenz, K. Nursing and the Future of Palliative Care. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 5, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radbruch, L.; De Lima, L.; Knaul, F.; Wenk, R.; Ali, Z.; Bhatnaghar, S.; Blanchard, C.; Bruera, E.; Buitrago, R.; Burla, C.; et al. Redefining Palliative Care-A New Consensus-Based Definition. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, 754–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etkind, S.N.; Bone, A.E.; Gomes, B.; Lovell, N.; Evans, C.J.; Higginson, I.J.; Murtagh, F.E.M. How Many People Will Need Palliative Care in 2040? Past Trends, Future Projections and Implications for Services. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicely Saunders International You Matter Because You Are You. An Action Plan for Better Palliative Care. Available online: https://csiweb.pos-pal.co.uk/csi-content/uploads/2021/01/Cicely-Saunders-Manifesto-A4-multipage_Jan2021-2.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Deravin, L.; Anderson, J.; Croxon, L. Are Newly Graduated Nurses Ready to Deal with Death and Dying?—A Literature Review. Nurs. Palliat. Care 2016, 1, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, S.; Del Fabbro, E.; Bruera, E. Symptom Control in Palliative Care—Part I: Oncology as a Paradigmatic Example. J. Palliat. Med. 2006, 9, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekse, R.J.T.; Hunskår, I.; Ellingsen, S. The Nurse’s Role in Palliative Care: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e21–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henoch, I.; Browall, M.; Melin-Johansson, C.; Danielson, E.; Udo, C.; Johansson Sundler, A.; Björk, M.; Ek, K.; Hammarlund, K.; Bergh, I.; et al. The Swedish Version of the Frommelt Attitude Toward Care of the Dying Scale: Aspects of Validity and Factors Influencing Nurses’ and Nursing Students’ Attitudes. Cancer Nurs. 2014, 37, E1–E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, D.; Akca, N.K.; Simsek, N.; Zorba, P. Student Nurses’ Attitudes toward Dying Patients in Central Anatolia. Int. J. Nurs. Knowl. 2014, 25, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagelin, C.L.; Melin-Johansson, C.; Henoch, I.; Bergh, I.; Ek, K.; Hammarlund, K.; Prahl, C.; Strang, S.; Westin, L.; Österlind, J.; et al. Factors Influencing Attitude toward Care of Dying Patients in First-Year Nursing Students. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2016, 22, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knaul, F.M.; Farmer, P.E.; Krakauer, E.L.; De Lima, L.; Bhadelia, A.; Jiang Kwete, X.; Arreola-Ornelas, H.; Gómez-Dantés, O.; Rodriguez, N.M.; Alleyne, G.A.O.; et al. Alleviating the Access Abyss in Palliative Care and Pain Relief-an Imperative of Universal Health Coverage: The Lancet Commission Report. Lancet 2018, 391, 1391–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radbruch, L.; Knaul, F.M.; de Lima, L.; de Joncheere, C.; Bhadelia, A. The Key Role of Palliative Care in Response to the COVID-19 Tsunami of Suffering. Lancet 2020, 395, 1467–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.E.; Goebel, J.R.; Kim, Y.S.; Dy, S.M.; Ahluwalia, S.C.; Clifford, M.; Dzeng, E.; O’Hanlon, C.E.; Motala, A.; Walling, A.M.; et al. Populations and Interventions for Palliative and End-of-Life Care: A Systematic Review. J. Palliat. Med. 2016, 19, 995–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Integrating Palliative Care and Symptom Relief into Primary Health Care: A WHO Guide for Planners, Implementers and Managers. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274559 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Rosa, W.E.; Gray, T.F.; Chow, K.; Davidson, P.M.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Karanja, V.; Khanyola, J.; Kpoeh, J.D.N.; Lusaka, J.; Matula, S.T.; et al. Recommendations to Leverage the Palliative Nursing Role During COVID-19 and Future Public Health Crises. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. JHPN Off. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurses Assoc. 2020, 22, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, W.E.; Krakauer, E.L.; Farmer, P.E.; Karanja, V.; Davis, S.; Crisp, N.; Rajagopal, M.R. The Global Nursing Workforce: Realising Universal Palliative Care. Lancet. Glob. Health 2020, 8, e327–e328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, C.; Roberts, R.; Martz, K.; Perry, J.; Tivis, L.J. Communicating with Patients and Their Families about Palliative and End-of-Life Care: Comfort and Educational Needs of Nurses. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2015, 21, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smothers, A.; Young, S.; Dai, Z. Prelicensure Nursing Students’ Attitudes and Perceptions of End-of-Life Care. Nurse Educ. 2019, 44, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiel, M.; Harden, K.; Brazier, L.-J.; Marks, A.; Smith, M. Improving the Interdisciplinary Clinical Education of a Palliative Care Program through Quality Improvement Initiatives. Palliat. Med. Rep. 2020, 1, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Explanation of Palliative Care. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Available online: http://www.nhpco.org/palliative-care-0 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

| Method | Description | Period |

|---|---|---|

| Lectures | Lectures were delivered using the Flipped classroom method, synchronously and asynchronously. Synchronous through the Zoom meeting application, and teaching videos and materials uploaded at the Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) platform, powered by LiVE Unpad. Lectures were given by academic lecturers, hospital practitioners, and community practitioners, both from within and outside the country, and lecturers from Universitas Padjadjaran. | 4 days (day 1–4) |

| Problem-based study/case study | Students strengthened the concept of PCN through pre-designed cases. This strategy was aimed to prepare the students before they encounter with the real patients. | 1 day (day 4) |

| Real case study | Students provided palliative patients through telenursing under the supervision of the assigned academics (one for each group). Students carried out nursing care, which included assessment, determining nursing diagnoses, developing nursing care planning, and implementing, evaluating, and writing documentation. | 5 days (days 5–11) |

| Project-based | Students learned to provide health education to their patients and the patients’ families through project-based study. Students were asked to compile educational media that has been used in providing health education to patients. The media was then shared with other students and lecturers through an exhibition event. Media used for health education include posters, booklets, android applications, videos, and others. | 4 days (day 8–12) |

| Roleplay | Students were asked to do a role play about how to communicate with palliative patients. | 1 day (day 4) |

| Discussion | Discussions and questions and answers were held at any time as needed either synchronously or asynchronously. | Every day if needed |

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 22 | 13.4 |

| Female | 142 | 86.6 |

| Age (year); Mean (SD) | 23.3 (0.756) | IR (21–26) |

| <25 | 155 | 94.2 |

| ≥25 | 9 | 5.5 |

| GPA (4.00); Mean (SD) | 35.1 (0.196) | IR (3.06–3.940) |

| <3.25 | 19 | 11.6 |

| 3.26–3.70 | 116 | 70.7 |

| >3.70 | 29 | 17.7 |

| NPC course in undergraduate (pre-clinic) | ||

| Yes | 163 | 100 |

| No | 0 | 0 |

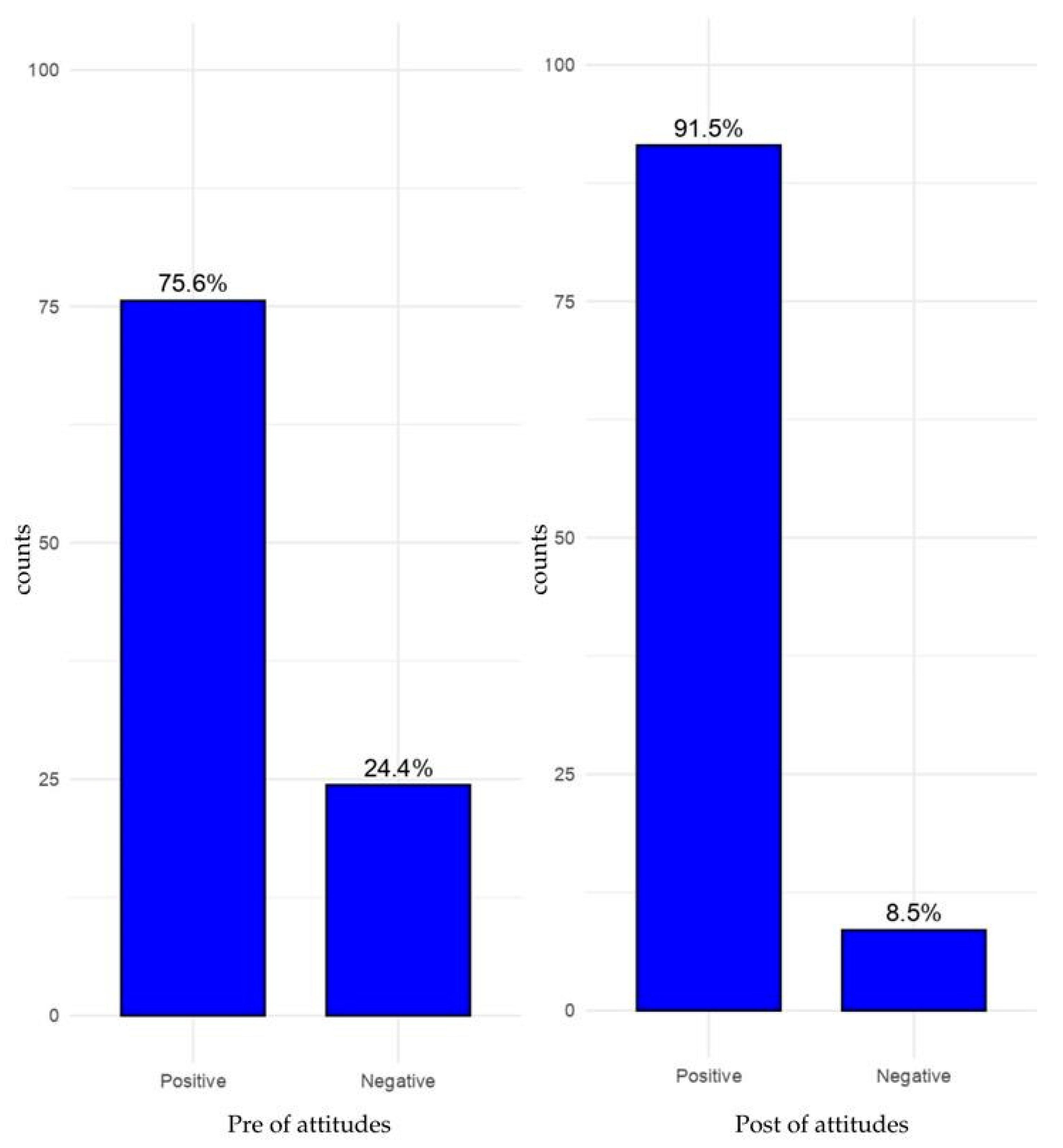

| Attitudes towards PCN | ||

| Positive | 124 | 75.6 |

| Negative | 40 | 24.4 |

| Witnessed dying people in family | ||

| Yes | 142 | 86.6 |

| No | 22 | 13.4 |

| Variable | Pre- (Mean, SD) | Post- (Mean, SD) | MD | 95% CI (Lowe; Upper) | t | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | 10.24 (1.83) | 10.98 (1.88) | −0.738 | −0.484; −0.170 | −4.20 | <0.001 |

| Theory and principles of PC | 1.94 (0.80) | 2.09 (0.82) | −0.152 | −0.306; 0.002 | −1.95 | 0.053 |

| Psychosocial and spiritual care | 0.54 (0.67) | 0.62 (0.72) | −0.086 | −0.291; −0.016 | −1.76 | 0.08 |

| Pain and other symptom management | 7.76 (1.40) | 8.26 (1.30) | −0.500 | −0.464; −0.151 | −3.95 | <0.001 |

| Attitudes | 103.35 (8.57) | 108.29 (8.94) | −4.933 | −0.776; −0.443 | −7.82 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Squares | F | p | η2 | ω2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | |||||||

| WDP | 2.869 | 1 | 2.676 | 0.758 | 0.385 | 0.005 | −0.001 |

| GPA | 8.027 | 2 | 4.254 | 1.205 | 0.322 | 0.015 | 0.003 |

| WDP × GPA | 0.250 | 2 | 0.173 | 0.049 | 0.952 | 0.001 | −0.012 |

| Residuals | 554.921 | 157 | 3.529 | ||||

| Attitudes | |||||||

| WDP | 77.7 | 1 | 77.7 | 0.971 | 0.326 | 0.006 | −0.000 |

| GPA | 204.5 | 2 | 102.2 | 1.278 | 0.281 | 0.016 | 0.003 |

| WDP × GPA | 205.7 | 2 | 102.9 | 1.286 | 0.279 | 0.016 | 0.003 |

| Residuals | 12558.5 | 157 | 80.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haroen, H.; Mirwanti, R.; Sari, C.W.M. Knowledge and Attitude toward End-of-Life Care of Nursing Students after Completing the Multi-Methods Teaching and Learning Palliative Care Nursing Course. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4382. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054382

Haroen H, Mirwanti R, Sari CWM. Knowledge and Attitude toward End-of-Life Care of Nursing Students after Completing the Multi-Methods Teaching and Learning Palliative Care Nursing Course. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4382. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054382

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaroen, Hartiah, Ristina Mirwanti, and Citra Windani Mambang Sari. 2023. "Knowledge and Attitude toward End-of-Life Care of Nursing Students after Completing the Multi-Methods Teaching and Learning Palliative Care Nursing Course" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4382. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054382

APA StyleHaroen, H., Mirwanti, R., & Sari, C. W. M. (2023). Knowledge and Attitude toward End-of-Life Care of Nursing Students after Completing the Multi-Methods Teaching and Learning Palliative Care Nursing Course. Sustainability, 15(5), 4382. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054382