1. Introduction

Historically, the backbone of indoor lighting design has been illuminance, measured with the illuminance, or ‘lux’, meter. More specifically, the lighting design task has been to guide the application of light to meet recommended levels of illuminance on the working plane. However, new lighting measurement tools are available, including luminance meters, imaging photometers, and spectroradiometers, which capture more visually relevant dimensions of lighting such as light distribution and spectrum. Assessing more dimensions of lighting has the potential to improve lighting practice, as lighting can be more effectively tailored to meet the full gamut of visual needs. However, these information-rich tools are yet to be integrated into lighting design practice.

Imaging photometers, also known as luminance imaging devices, are a data-rich measurement tool that capture luminance maps, which are analogous to an image wherein each pixel represents a luminance reading. Luminance maps capture the distribution of light in the surrounding lit environment and closely reflect human vision. Luminance imaging devices capture light for a view like a camera. Because reflected light can vary with angle, multiple locations and orientations of the image normal are required to fully characterise a lit environment.

Fundamental visual parameters such as visual size, target contrast, and object luminance may be extracted from a luminance map and used to derive a comprehensive suite of lighting measures. Therefore, the use of luminance maps can guide the more effective design of lighting, more closely matching the application of light to the underlying visual need. By contrast, illuminance measurements cannot evaluate all these visual parameters and thus form a lower-resolution lighting measurement device. Overall, luminance maps and their derived lighting measures enable better performing and more efficient lighting by directing light to meet the underlying visual need and eliminate wasteful over-lighting.

Luminance-based lighting design also enhances passive lighting design, as existing daylight methods are driven and constrained by illuminance targets, which relate poorly to visual needs. Adopting a luminance basis for daylighting design enables the sufficiency of natural lighting to be evaluated directly against the fundamental visual needs, and thus is a more specific basis for design. Through eliminating wasteful artificial over-lighting, enhancing daylighting design will lead to lower energy use, greener buildings, and overall enhanced sustainability. Additionally, designing closer to visual needs guarantees lighting performance and minimises visual strain, which leads to better performing and healthier buildings.

Despite the benefits of luminance maps and measures, a luminance basis does not exist as a clear alternative to illuminance-based lighting design. For the practitioner, it is unclear which luminance measures are available, how these measures should be applied, and whether these measures form a comprehensive alternative method to the current illuminance-based lighting design. These questions raise a more fundamental question: “what is required from a lighting design method?”

This paper is divided into four six sections.

Section 2 covers the relevant background of the topic and makes the case for a luminance-based lighting practice.

Section 3 addresses the question of what is required from a lighting design method by reviewing current and alternative lighting design measures and methods to elucidate the key requirements for lighting design. Lighting “measure” is defined here as a single lighting calculation, such as working plane illuminance or Unified Glare Index, and lighting “method” is defined as a suite of measures employed for a full lighting design. The results of this review are presented as a framework to meaningfully define and compare different lighting design measures and methods. In

Section 4, luminance measures are reviewed. In

Section 5, an alternative luminance-based lighting method is presented and demonstrated as a sufficient replacement to the current illuminance-based practise, in the context of the framework presented.

Section 6 concludes the research and summarizes key takeaways.

2. Background

Illuminance (lx, lm/m

2) is the foundation of lighting design. Task illuminance at the working plane, a horizontal plane at working height, is required for compliance to many lighting standards [

1] and is recommended in design guides [

2,

3]. Illuminance is typically measured from illuminance, also called ‘lux’, meters, although it can also be derived from luminance maps [

4]. The devices accept light from the surrounding hemisphere and the read out is equivalent light flux incident on the plane of the device at that point in space. Typically, a grid of measurements will be taken across the area of interest to capture the average illumination and its uniformity. Although any device orientation may be used, the most common measurement orientation is the horizontal plane; however, the vertical plane, or vertical illuminance, is also used.

The key measures and recommendations in the currently accepted lighting design methodology, the Working Plane Illuminance (WPI) method, include illuminance uniformity, glare index, and colour rendering index [

5]. The WPI method assumes that these measures, in combination, will ensure adequate visual conditions.

The WPI method was developed using historically available technology. However, the emergence of new light-measurement technologies means that WPI is no longer the best way to incorporate visual science into lighting design. Technological development has enabled accurate luminance meters [

6], imaging photometers [

7], custom luminance imaging devices [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], 360° high dynamic range imaging tools [

17,

18], custom quasi-spectral imaging radiometers [

19], and lighting modeling software packages [

20] for measuring or modeling luminance and luminance maps. Luminance maps capture the distribution of light in the surroundings, which is reflected or direct light in the environment, and can be expressed with luminance images, where each pixel represents a luminance measurement of the surroundings.

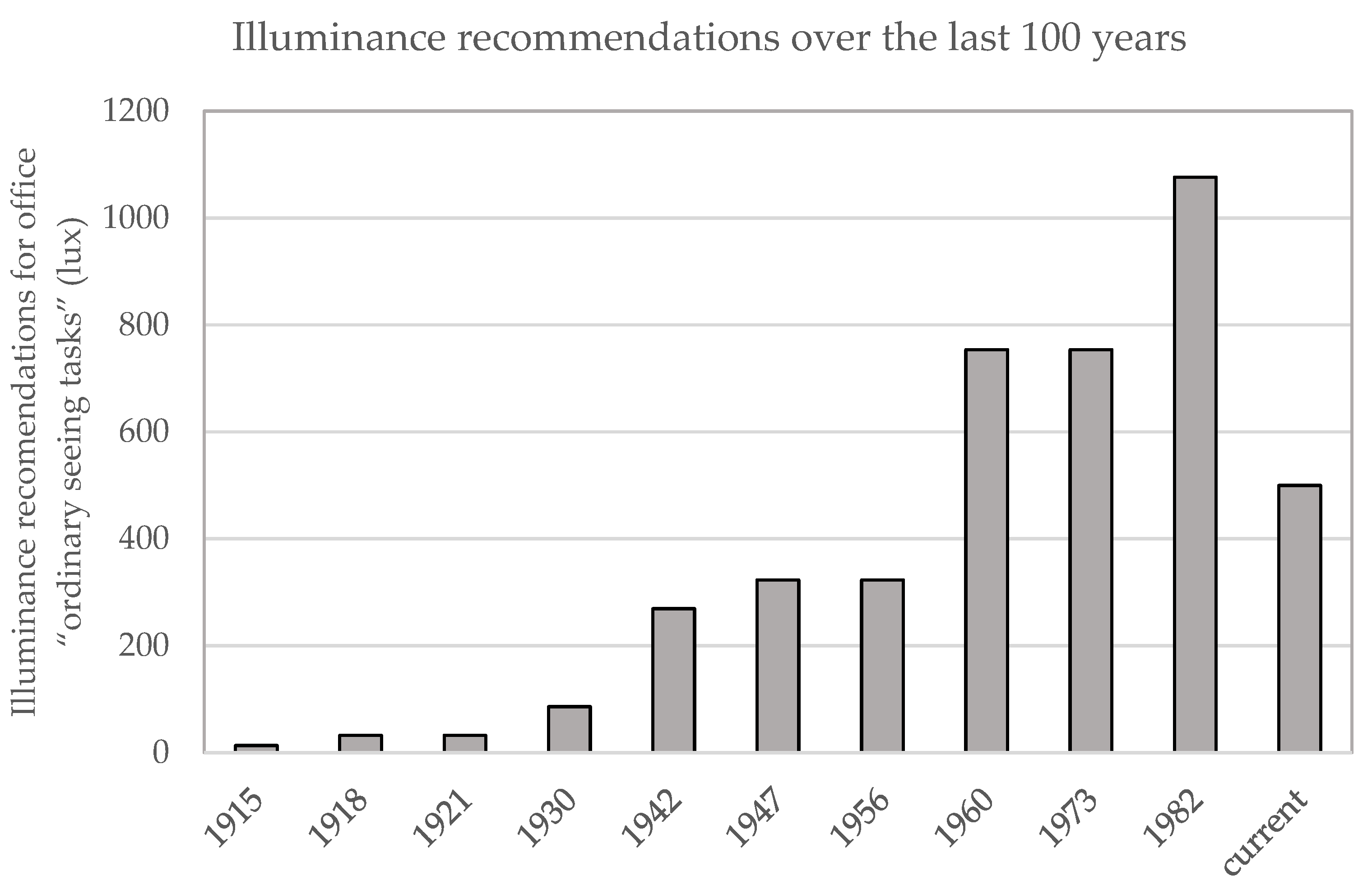

Furthermore, the WPI method and associated recommended levels are imprecise. Illuminance recommendations, and the consensus basis for their derivation, have attracted criticism for being guided by factors other than visual needs [

21], such as economic and technological forces. These outside drivers may thus better explain their significant variation over their century of use, as shown in

Figure 1.

In addition, the movement away from a criteria-based approach and towards single-zone-based illuminance recommendations has attracted criticism for providing largely arbitrary values [

24]. The recommended illuminance levels also map poorly to the visual requirements for performance or preference. For example, visual performance for dark 10 pt text on standard office paper, a common office reading task, is saturated at 25 lux [RVP = 0.95] (80% contrast, 30-year-old observer, 1 m reading distance) [

25], which is far lower than the typical recommended levels of 300 to 500 lux. This low requirement corresponds to the experience of successfully reading in dim lighting. Finally, visual preference by workplace illuminance is highly individual and does not correlate well with recommended levels: self-selected illuminance values can vary between 200 and 700 lux [

26].

The imprecision of illuminance may be due to the fact that illuminance readings include or condense many lighting components, such as background and target luminance, workstation luminance and contrast, room surface luminance, and contrast. Importantly, each of these components can affect performance and preference, and would be better assessed as separate elements. Such independent consideration of each element cannot be done using illuminance but can be done with luminance maps.

Overall, the key visual parameters in the WPI method are not directly evaluated. Instead, the critical lighting elements are measured either indirectly, as with visual performance where illuminance values are used as a proxy, estimated by simulation, as with discomfort glare or daylighting glare, or left unassessed, as with disability glare. Hence, the WPI method, and illuminance measures in general, is a less direct method, which is used largely due to the difficulty in obtaining accurate luminance maps.

In contrast, luminance maps are a better measure than illuminance for lighting design, as they directly assess key visual parameters, are more data-dense, and can be used to evaluate a comprehensive suite of lighting measures. Luminance maps can be used to directly assess known key visual parameters, including visual size (steradians), location in the field of view (FOV), object luminance, and luminance contrast. These visual parameters can be used to evaluate critical visual requirements, such as visual detection threshold [

27], visual performance [

27], and glare, including discomfort glare [

28] and disability glare [

28].

Luminance maps are more data-dense and can be used to evaluate a greater set of lighting measurements compared to illuminance measurements. A luminance map contains the distribution of light intensity over the FOV, which could correspond to millions of readings depending of the resolution of the image. In an illuminance measurement, this distribution is lost as it is consolidated into a single reading, and thus a great deal of data is lost.

More specifically, luminance maps may be used to derive a large set of lighting measures, including relative visual performance (RVP) [

25], disability and discomfort glare measurements [

28,

29], various lighting quality metrics [

30,

31], alternative lighting metrics such as mean room surface exitance (MRSE) [

32,

33], and even illuminance [

4]. Alternative illuminance measures exist that can also be assessed with luminance maps and include cylindrical illuminance [

27], cubic illuminance [

34,

35], and vertical illuminance [

3,

23]. Thus, while alternative illuminance measures exist and add data compared to working plane readings, these measures still do not encode the same level of data as luminance maps, nor can they be used to evaluate the same suite of lighting measures as luminance maps.

Overall, luminance maps have greater specificity than illuminance measures. They capture light distribution, which has been noted as a missing piece in lighting design [

36], and are a well-suited tool for a wide range of lighting measures [

31]. The adoption of luminance-map-based lighting design as a replacement, or addition, to the illuminance-based method of measurement offers a large opportunity to evolve lighting design into a new era with better performing and more efficient lighting by designing lighting systems to directly meet underlying visual requirements.

3. Requirements for Lighting Design

Lighting design has emerged out of historically available technologies, visual science, and evolving needs for lighting [

37]. As such, lighting design has not been explicitly “designed” to set criteria. To better understand the context of lighting requirements, we took a retrospective approach that drew from a range of commentary, current practice, and proposed alternative lighting measures that highlight perceived gaps in current practice. This review was used to make a framework by which to compare different lighting design measures and methods on the same basis.

3.1. Human Needs Served by Lighting and CSP

The Illumination Engineering Society of North America (IESNA) lighting handbook [

30] outlines the range of human needs served by lighting, which include (1) visibility; (2) visual comfort; (3) aesthetic judgment; (4) task performance; (5) social communication; (6) mood and atmosphere; (7) health, safety, and well-being. The list of needs does not clearly separate the visual need, such as visibility, from the application, such as task performance, social communication, or safety. More specifically, the first three needs are primarily visual factors (visibility, visual comfort, and aesthetic judgement (appearance)), and the latter (4–7) are ill-defined or specific applications of the first three.

The CSP index was developed to determine lighting satisfaction [

38]. The model assumes a three-factor basis to lighting quality: Comfort, Satisfaction, and Performance. The index assesses Comfort as the absence of glare, Satisfaction regards the appearance of people and objects in the office and is evaluated as a ratio between vertical cylindrical illuminance and horizontal illuminance, and Performance includes the illuminance, uniformity, and Colour Rendering Index. The CSP index is comprised of a series of correlations for users in offices where computer monitors are used and those where they are not. The index provides a single number, which has been correlated to lighting satisfaction. In the CSP index, lighting distribution is handled as a ratio between vertical and horizontal illuminance, or direct and indirect illumination, instead of conducting the more detailed evaluation of lighting distribution that is possible with luminance maps. As such, it overlooks preferred lighting variation within view, which has been identified as a flaw of the model [

38].

3.2. The Working Plane Illuminance (WPI) Lighting Design Methodology

Working plane illuminance is the illuminance level provided at the working plane, defined as a horizontal plane at a task-specific height, such as desk height for office work. The WPI method is a lighting design method utilizing working plane illuminance, illuminance uniformity, a discomfort glare rating such as the Unified Glare Rating (UGR), and a colour rendering index (CRI). This lighting method is employed in guidance documents from institutions such as SLL [

23] and the IESNA [

3], as well as in various standards [

1].

The illuminance recommended for offices ranges from 200–700 lux [

26], with recommended levels increasing for visually difficult tasks, or where higher working speed and greater attention are required. Illuminance uniformity is specified to ensure adequate illuminance throughout the working area, as overhead lighting naturally produces variable levels of illumination. Uniformity is generally expressed as the ratio of minimum illuminance to average working plane illuminance. However, formulations can vary. Typical minimum uniformity values for offices are between 0.7 and 0.9, with higher values where task performance is more critical [

23].

Discomfort glare is produced by high luminance–contrast ratios. The visual system is more sensitive to high luminance in certain regions of the FOV [

39]. The most commonly used metric for discomfort glare for indoor lighting is the Unified Glare Rating (UGR) [

40]. Typical maximum UGR values range from 13 to 30 [

23,

41].

Colour appearance is a function of surface properties and the incident light wavelength composition. The colour rendering index (CRI) is a 0 to 100 scale used to ensure faithful colour reproduction as related to a standard light source [

5].

3.3. Alternative Lighting Design Measures

Alternative bases for lighting design have been proposed. They typically arise from observed shortcomings in the WPI method and thus highlight its gaps. These gaps can be used to address where WPI methods may be improved, or where it misses key requirements.

Alternative illuminance measures include vertical illuminance, cylindrical illuminance, and cubic illuminance. Vertical illuminance is mentioned in guidance documents for lighting whiteboards in education settings and storage racking in warehousing [

23], although values are not specified. Cylindrical illumination is the illuminance falling on the surface of a vertically orientated cylinder and is specified for social communication in office settings [

42]. Semi-cylindrical illumination is used for street lighting applications [

42]. Cubic illumination [

34,

35] involves six illuminance measurements about a point corresponding to the faces of a cube. These six measurements capture light directionality at a point and are used to calculate other illuminance measures, such as vertical or cylindrical illuminance [

34].

Mean room surface exitance (MRSE) is a measure of the reflected light in a room, and, as such, gives an indication of the overall ambient light level [

32]. Exitance is the visible light reflected or emitted from a surface per unit area, and mean room surface exitance is the geometric average of all the exitance of interior surfaces. MRSE correlates better than illuminance to Perceived Adequacy of Illumination (PAI) [

43].

Alternative illuminance measures (vertical, cylindrical, and cubic) highlight the need to also assess the directionality of light beyond the working plane. Directionality is important for vertical task performance and social communication, and assessing lighting in multiple directions is an important requirement for a lighting design method. MRSE also highlights the need to consider reflected light (surface exitance), rather than surface illumination. MRSE and exitance, in general, consider both incident illuminance as well as surface reflectance. As such, MRSE introduces more elements into lighting design.

3.4. A Framework for Lighting Design Methods

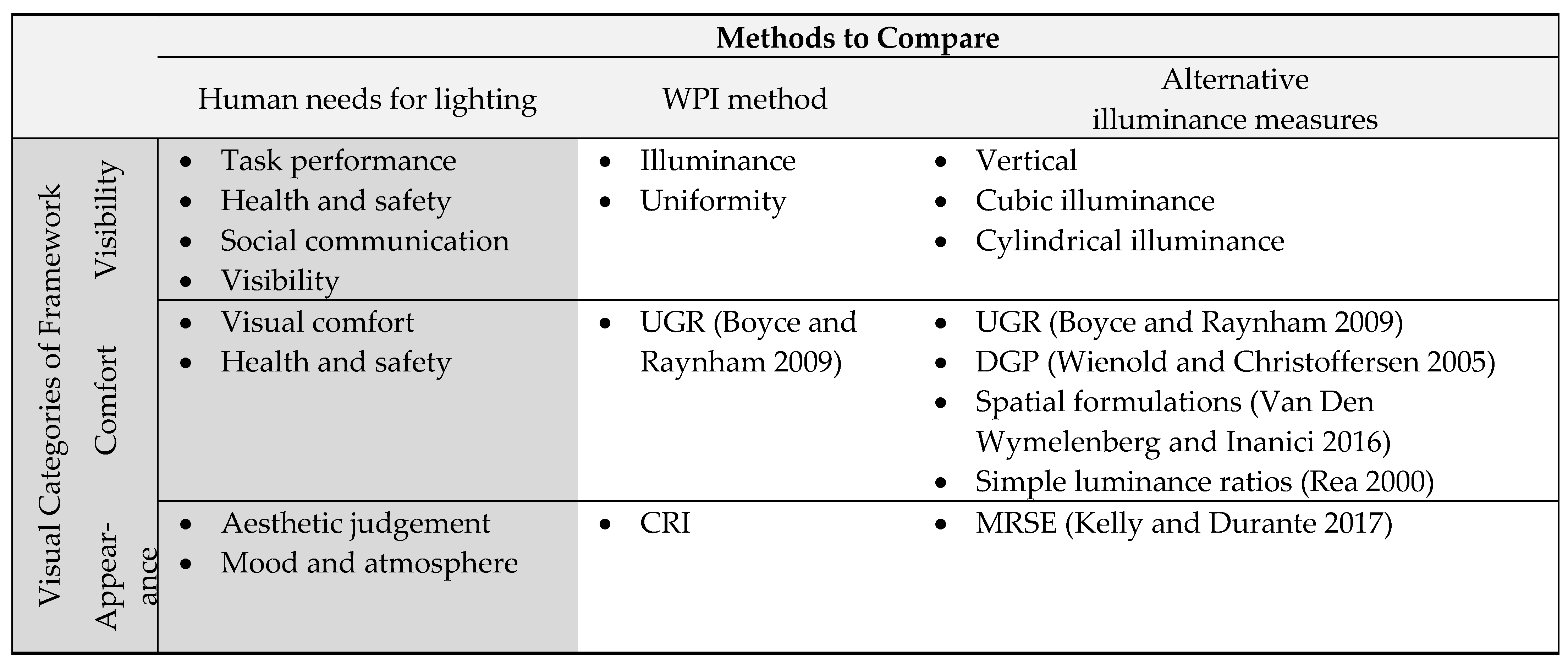

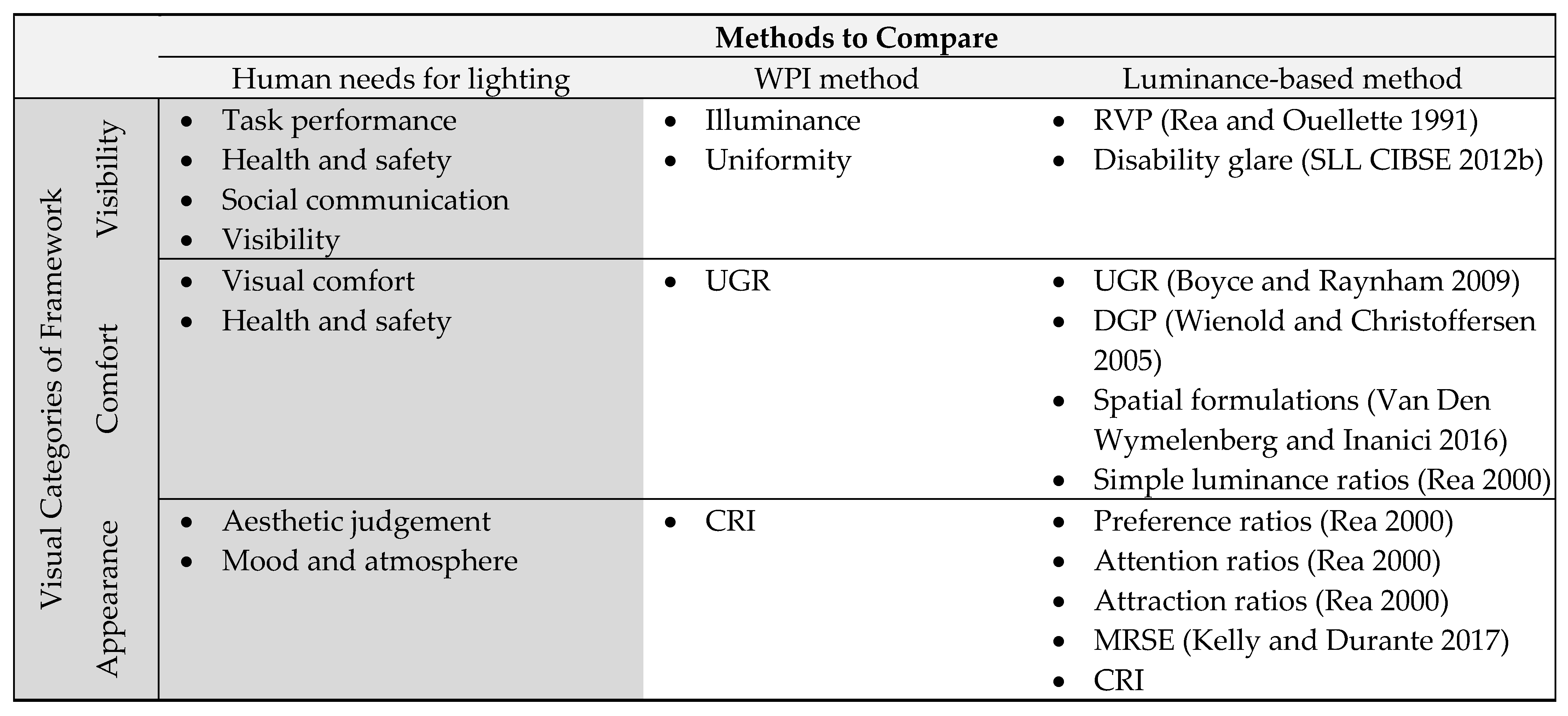

Given this discussion of current and alternative measures and outline of human needs and requirements,

Figure 2 presents a simple three-factor framework to compare lighting design measures and methods. In particular, this framework is intended to meaningfully compare alternative lighting methods to the WPI method. In this framework, aspects of lighting design are divided into three broad visual categories: Visibility; Comfort; and Appearance. Any method may be compared by how accurately and comprehensively it assesses all categories and associated needs.

A retrospective approach was used to determine the requirements for lighting design, wherein three sources of information were reviewed to assess lighting design from a multi-perspective approach. Firstly, commentary and existing frameworks such as the “human needs for lighting” and CSP index were reviewed. Secondly, current lighting design practice (the WPI method) was reviewed, as it is expected that current practice can implicitly reveal lighting requirements. Thirdly, alternative lighting measures were reviewed, as these highlight perceived gaps, i.e., lighting requirements that are inadequately met, in current practice. Where multiple perspectives converged, the common ground represented a grounded set of lighting requirements.

From these reviews, three factors emerged as visual categories that can organise all identified visual needs and the lighting measures that serve to fulfil them. These categories are Visibility, Comfort, and Appearance. While these categories are similar to the three assumed factors in the CSP model [

38], they have been justified by a multi-perspective approach. Additionally, where Satisfaction is related to the appearance of people and objects in the CSP model, in this work, the term “Appearance” is used, as “Satisfaction” is beyond the scope of a single visual category. These three categories map well to the identified ‘needs for lighting’, the lighting measures used in current practice, and alternative measures, as seen in the rows of

Figure 2. The categories are also largely independent, as comfort has minimal impact on visibility, visibility on appearance, and so forth. Overall, the framework is a suitable platform for comparing lighting design measures and methods.

As can be seen, each human need for lighting is reflected in the more fundamental visual requirements, which define the framework in

Figure 2. For example, task performance, social communication, and health and safety are purely, or in large part, expressions of visibility, with only the object or task changing. The same principle is true for the other visual requirements in

Figure 2. Some human needs for lighting have two visual components. For example, health and safety is a function of visibility and comfort, which could be divided as the need to safely navigate a room (Visibility) and the need to be free from persistent or intense discomfort (Comfort). A complete system or method would have entries in every row for the column it occupies for comparison.

The elements of the WPI design method were fitted within the framework of

Figure 2. Each of the key measures was fit into a category. Visibility is assessed by working plane illuminance and uniformity. Comfort is assessed by UGR, and appearance is assessed with CRI. While uniformity will affect appearance, the stated purpose is to ensure minimum illuminance, and so was attributed only to visibility.

Using this framework, lighting methods and measures may be compared. Two terms are useful for assessing the efficacy of methods and measures: ‘comprehensive’ and ‘accurate’. A ‘comprehensive’ method addresses all the visual categories. ‘Accurate’ assessment of a visual category relates to the evaluation of the underlying visual needs for an application. For example, Visibility is influenced both by target illuminance and disability glare. Assessing both components is more accurate than assessing only one. Equally, Visibility has many applications, or needs served, and incorporating measures assessing or applying to more applications is a more accurate assessment of the visual category. Thus, including Visibility measures that serve social communication, such as vertical illuminance, as well as task performance using working plane illuminance, would be more accurate than using only a single measure. In practice, measurement device accuracy will also affect how accurately the underlying visual needs are evaluated. However, in this work, the primary consideration and use of the term ‘accuracy’ relate to how lighting measures and methods map to visual requirements.

Under this framework, it should be direct and simple to determine whether an alternative lighting design methodology is sufficient to be used in place of the WPI method in the first column of methods compared in

Figure 2. If a lighting method is equally or more comprehensive and accurate than the WPI method, using these definitions, such a method would provide a suitable alternative.

Putting lighting measures in this framework also provides the opportunity to create a lighting method that best suits a particular lighting design application, where different applications could have their own weighting across the three visual categories. For example, a reception area with low requirements for visibility is justified in adopting MRSE as the primary design measure and ensuring adequate visibility by exceeding (very low) minimum illuminance levels. By contrast, a dental surgery with high visibility requirements and low expectations for appearance can use working plane illuminance targets. Thus, this framework provides justification for exercising flexibility to best meet application-specific needs.

Finally, the framework can be reformulated as knowledge grows. For instance, research is being conducted into the health effects of lamp spectral composition [

46]. This need for health does not fit well within the three visual categories presented in

Figure 2, but could be added as a fourth category. Hence, the framework is readily extensible. However, in the case of spectral assessment, neither luminance nor illuminance meters are suitable for this task, as they do not differentiate light spectra but give only the luminous power. Instead, spectroradiometers would be required.

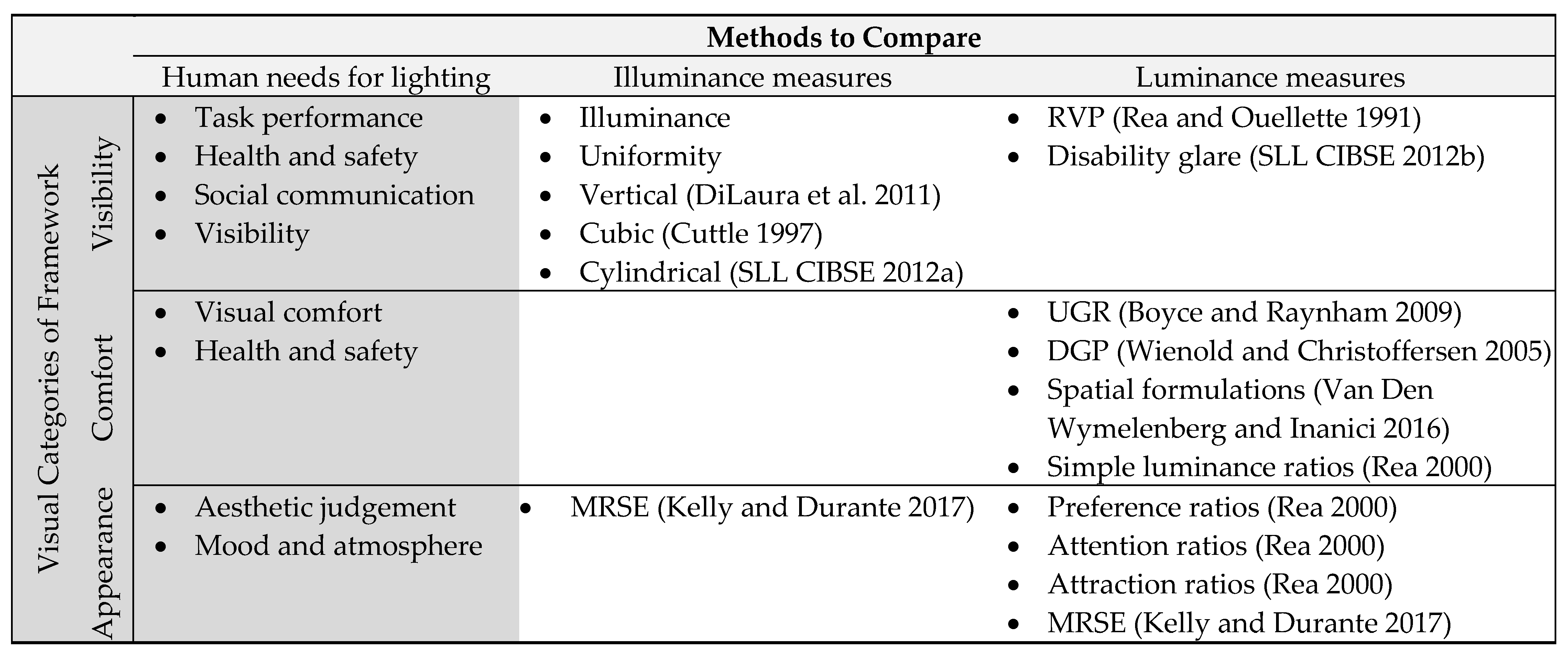

5. A Proposed Luminance-Based Lighting Design Method

We propose a luminance-based alternative to the WPI method using the three visual categories, which we compared to the WPI to demonstrate its justifiable substitution in lighting practice. The proposed luminance method requires each visual category to meet or exceed the WPI method. The proposed method and its measures are summarised using the framework of

Figure 2, as shown in

Figure 5.

Figure 5 directly compares the measures commonly employed in the WPI method and the proposed luminance-based lighting design method. As such, it is simple to compare the methods across each visual category.

5.1. Visibility

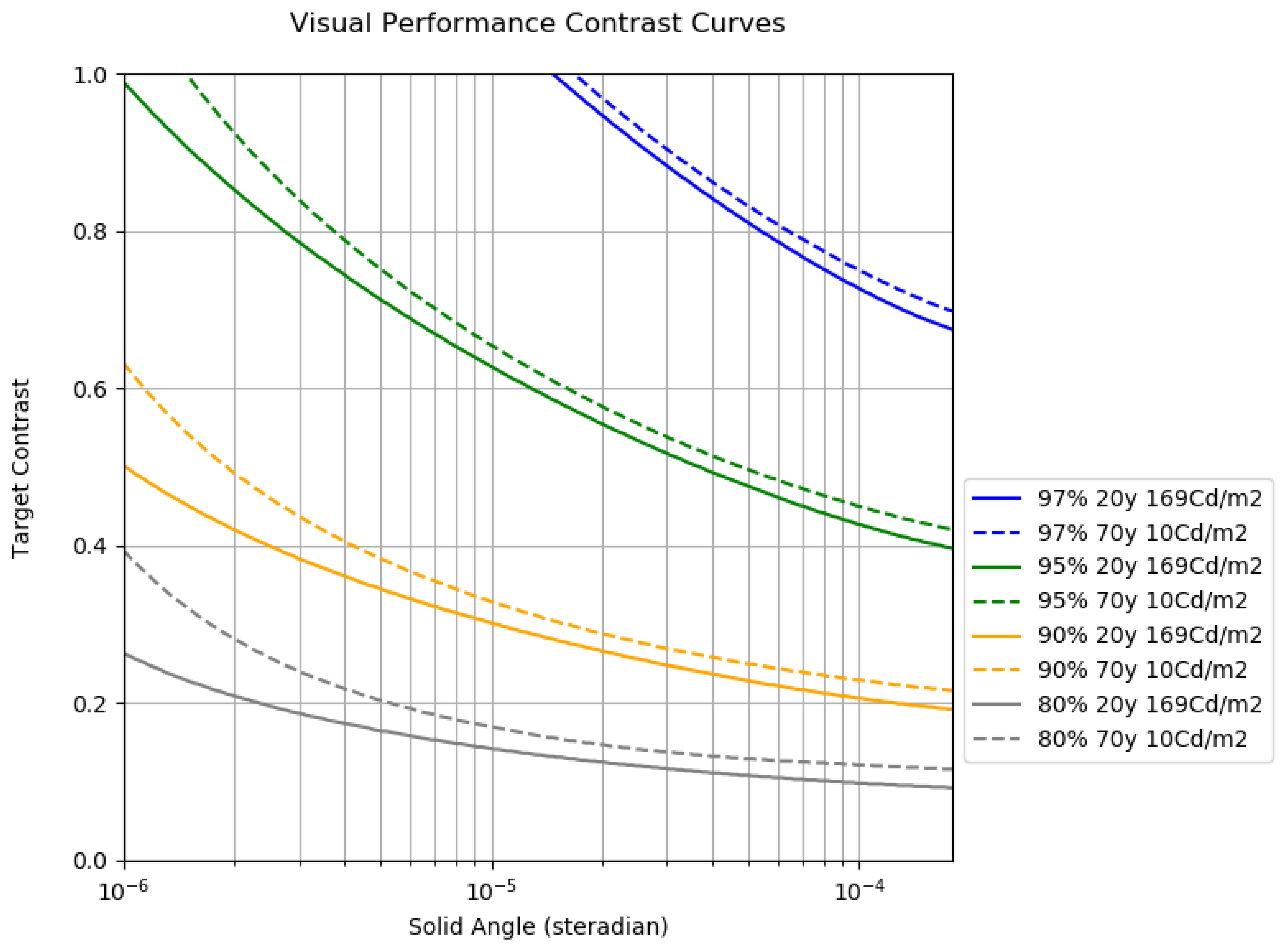

Visibility may be assessed by RVP and disability glare measures. For a given task, with a particular contrast, visual size, and RVP value, the two measures may be used to calculate the minimum target luminance (or background luminance) values required for performance. RVP calculations can be simplified and made more conservative by removing the observer age parameter by assuming a value of 70 years, the model upper limit.

In the first instance, a justifiable RVP target can be found using RVP of the relevant task under comparable recommended working plane illuminance levels (RVPWP). This approach guarantees that Visibility meets or exceeds the WPI method. If RVPWP is in the region of saturated visual performance, target luminance may be decreased with little or no penalty on performance, and a lower minimum target luminance is established. This approach ensures that over-lighting is minimised and performance is guaranteed by setting light levels to the need. In future, RVP targets should be independently established to avoid the ambiguity imposed by illuminance targets. Additionally, for many indoor lighting applications, the visibility requirements for lighting are low and minimum light levels are set by the needs for comfort and appearance, in which case, a full visibility analysis can be excluded.

The orientations or views that are evaluated are set by the task. For social communication, this view orientation is in the horizontal direction, comparable to a vertical plane. This requirement of luminance-based measures to assess lighting conditions in application-specific directions ensures that lighting is applied with the required directionality. However, this approach increases the number of orientations assessed and, consequently, the complexity and time burden for the Visibility assessment compared to the WPI method.

5.2. Comfort

Discomfort glare is derived from spatial luminance distributions in the FOV and is thus most natively and directly assessed with luminance maps. In a luminance-based design method, Comfort may be evaluated from a large suite of discomfort glare metrics, as shown in

Figure 5, which allows the most application-suitable metrics to be used. Therefore, luminance-based glare assessment is more accurate than glare assessment that is conducted with the WPI method, which is often limited to UGR and simplified to values provided by manufacturer tables or simple modelling.

In addition, daylight glare may be evaluated without additional effort, as high-quality modelling or measurement is already required and thus available. For equivalence with the WPI method, UGR should at a minimum be evaluated with design values taken from established standards.

5.3. Appearance

Appearance may be assessed using any of the following: luminance ratios to reproduce preferred conditions and highlight points of attention and attraction; MRSE for accurate indication of perceived room brightness, which may be assessed by luminance imaging; and CRI to account for faithful colour reproduction, managed by lamp selection. Where MRSE is typically captured with illuminance measurement, it can also be accurately captured with luminance-map measurement [

32]. At minimum, a luminance-based method should assess CRI to be equivalent to the WPI method.

Appearance design values can be found from standards and published research [

1,

3,

23]. CRI values may be taken from guidance or standards [

5]. Other dimensions of appearance, such as MRSE and preference–attention–attraction luminance ratios, have more flexibility with target values in published literature [

30,

32].

Luminance-based Appearance assessment captures many dimensions of appearance, particularly the variance and distribution of light in a space. By comparison, the WPI method employs only the CRI measure. However, guidance on surface reflectance values and uniformity will have an indirect effect on appearance. Overall, considering the range of measures available, Appearance assessment with luminance distributions is more accurate than the WPI method.

5.4. Technical Summary

The proposed luminance-based lighting design method can accurately assess the three key visual categories and the human needs for lighting they serve. Therefore, it is a comprehensive design method and an effective replacement for current practice. The increased accuracy of this method can lead to more efficient and better performing lighting design due to the precise application of light and direct evaluation of the fundamental lighting requirements.

Both task performance and discomfort glare analysis depend on the distribution and intensity of light in the FOV, which is dependent on time of day for daylight glare, and thus, metric evaluation depends on the view orientation of the luminance map. However, a number of key view orientations must be selected for a room lighting, increasing the complexity of the design beyond simple WPI illuminance assessment at the working plane. In contrast, these choices can be standardised by application or end-user preferences, and the added complexity provides a measurably better design outcome.

5.5. Practical Implications Summary

Our review-derived three-factor framework, review of luminance-based methods, and provided method of application in the translation of design values all help promote the uptake of luminance and alternative lighting measures by overcoming a knowledge barrier. Increased incorporation of accurate luminance-based measures drives improvements in lighting practice. Improvements include lighting efficiency increases by designing closer to lighting needs, eliminating over-lighting, and ensuring adequate performance across a wide range of lighting dimensions.

The framework for lighting design in

Figure 2 is a simple, effective tool for comparing lighting measures and methods. While it has been used here to construct a luminance-based design method, it is not limited to this application. Instead, it may be used to select specific measures best suited for a particular application to consequently improve lighting performance.

In addition, the three-factor lighting design framework may be expanded as more lighting design considerations and measures emerge. For example, the health effects of the lighting spectrum are being increasingly incorporated into lighting design [

46]. An additional factor of health could be added to the model to fit these emerging considerations. Interestingly, low-cost custom-imaging devices have also been used as quasi-radiometers [

19] and could capture this added dimension of lighting design.

The luminance-based design method presented is significantly more complex than the WPI method. The practitioner is required to determine key tasks, times, positions, and view orientations for the design in question, which introduces significant dimensionality to the problem and consequently requires increased modelling and measurement. While it is expected that increased use of luminance-based design methods will lead to a refining of the methods of application, at present, the complexity presents a significant barrier to luminance-based measurement uptake. In contrast to this perspective, the use of computers and CAD systems can enable the creation of these orientations and perspectives in simulation to better automate the process and potentially return the method to the early design phase for a given space.

Visibility design values are still based on current practice, and as such, the values may not accurately reflect all requirements. More specifically, RVP target values are set by taking the RVP values for the equivalent task under recommended working plane illuminance. These working plane illuminance targets are themselves inaccurate, as the minimum difference between zone-based illumination values in typical guidance is 50 lux, which may be 7–25% of the recommended value, for typical office settings. Instead, it would be more appropriate to establish an RVP based on the criticality of the task and to design to this value independent of the equivalent working plane recommendation.

Current commercial imaging photometers, which measure luminance distribution (luminance maps), are required to implement a luminance-based design method. However, they are currently prohibitively expensive. While custom low-cost alternative devices exist, these still rely on expensive calibration equipment. The expense of these devices is a significant barrier to the uptake of a luminance-based method, but one which may be addressed by emerging technologies and ideas using high-functioning mobile phone cameras.

6. Conclusions

The three-factor framework proposed in this study indicates that lighting design methods serve to fulfil three broad categories of visual needs: Visibility, Comfort, and Appearance. The framework provides a general and useful means to compare lighting methodologies and can be used to assess whether an alternative lighting-design method is as equally comprehensive and accurate as the WPI method, and thus could serve as an effective replacement. This framework is also readily extendable as additional factors and measurement device types are considered, such as the health and wellbeing effects of lighting and the use of spectral radiometers.

Luminance measures can provide an accurate and comprehensive alternative to the current working plane illuminance-based lighting design method. Implementing these luminance measures can lead to better performing and more efficient lighting. More detailed visibility assessment can be used to reduce light levels, while RVP and disability glare measures guarantee visibility by setting the lighting level in the task direction to the need, eliminating wasteful over-lighting. Direct comfort assessment leads to higher confidence in lighting comfort. Luminance-based glare assessment enables direct assessment of a wide range of glare metrics, providing for more direct, and thus accurate, glare assessment than the modelling methods used in the WPI method. Daylight glare, often left out of glare analyses, is easier to implement with luminance map assessment. Luminance-based appearance assessment includes many measures that cannot be evaluated with illuminance measurement, such as preference, attention, attraction contrast ratios, and MRSE. Thus, appearance assessment accuracy is greatly improved with the proposed luminance-based design method.

The flexibility offered by a luminance-based lighting design approach enhances passive lighting design. Light levels can be set by very low established minimums required for visual performance, then artificial lighting may be added effectively and, where required, to create the desired comfort and appearance.

The proposed luminance-based lighting design method is more complex than the WPI method. The practitioner must consider measures, locations, views, and times of day, as all these parameters can produce significantly different visual conditions. However, the added complexity provides for a measurably better design outcome. Additionally, the location/view/time combinations can both be simplified by considering the limiting conditions and standardised for common applications and end-user preferences.