Engaging Young People in Climate Change Action: A Scoping Review of Sustainability Programs

Abstract

1. Introduction

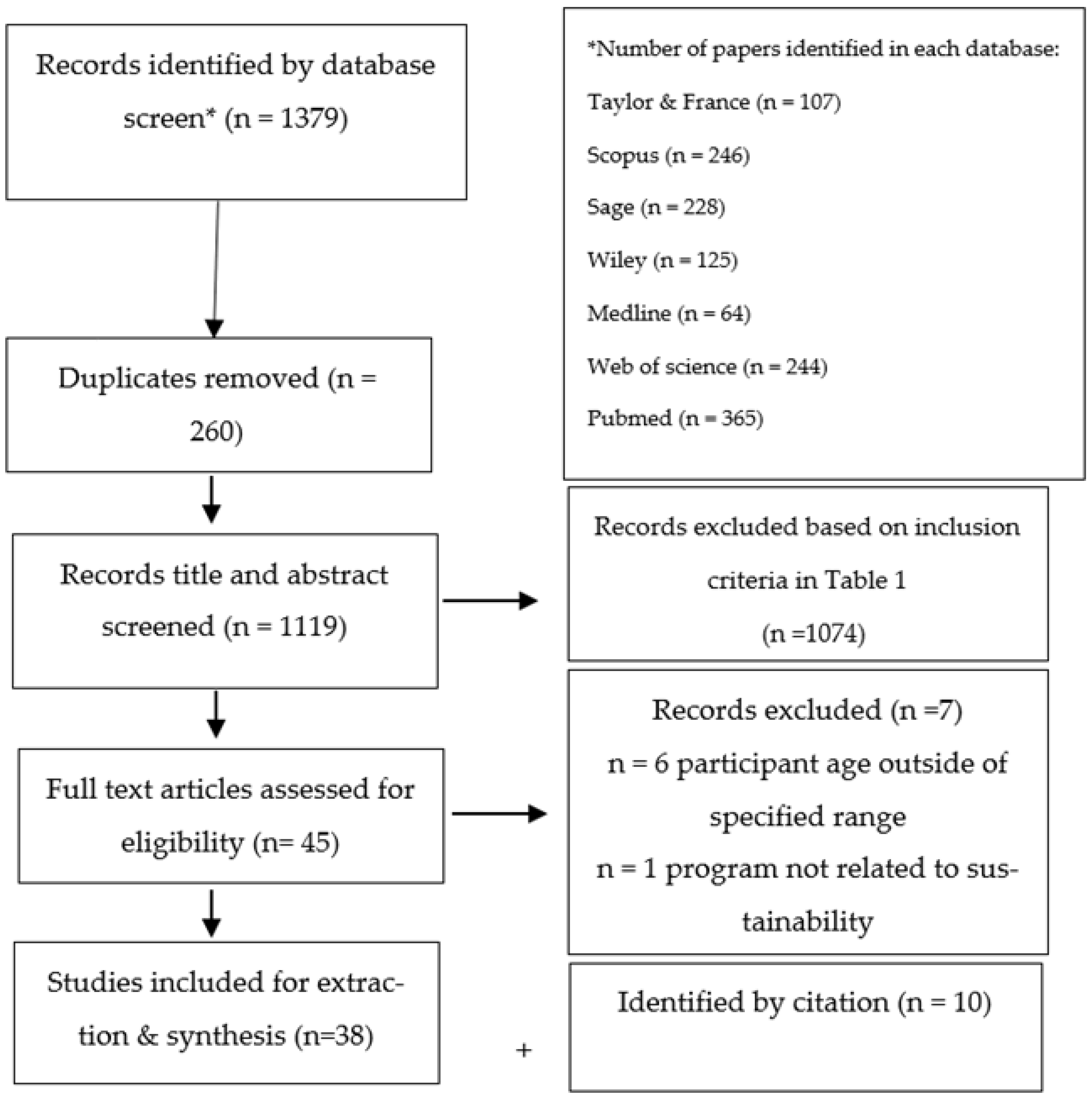

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Locations, Designs and Methods

3.2. Study Theories and Frameworks

3.3. Program Content and Activities

3.4. Outcome Measures

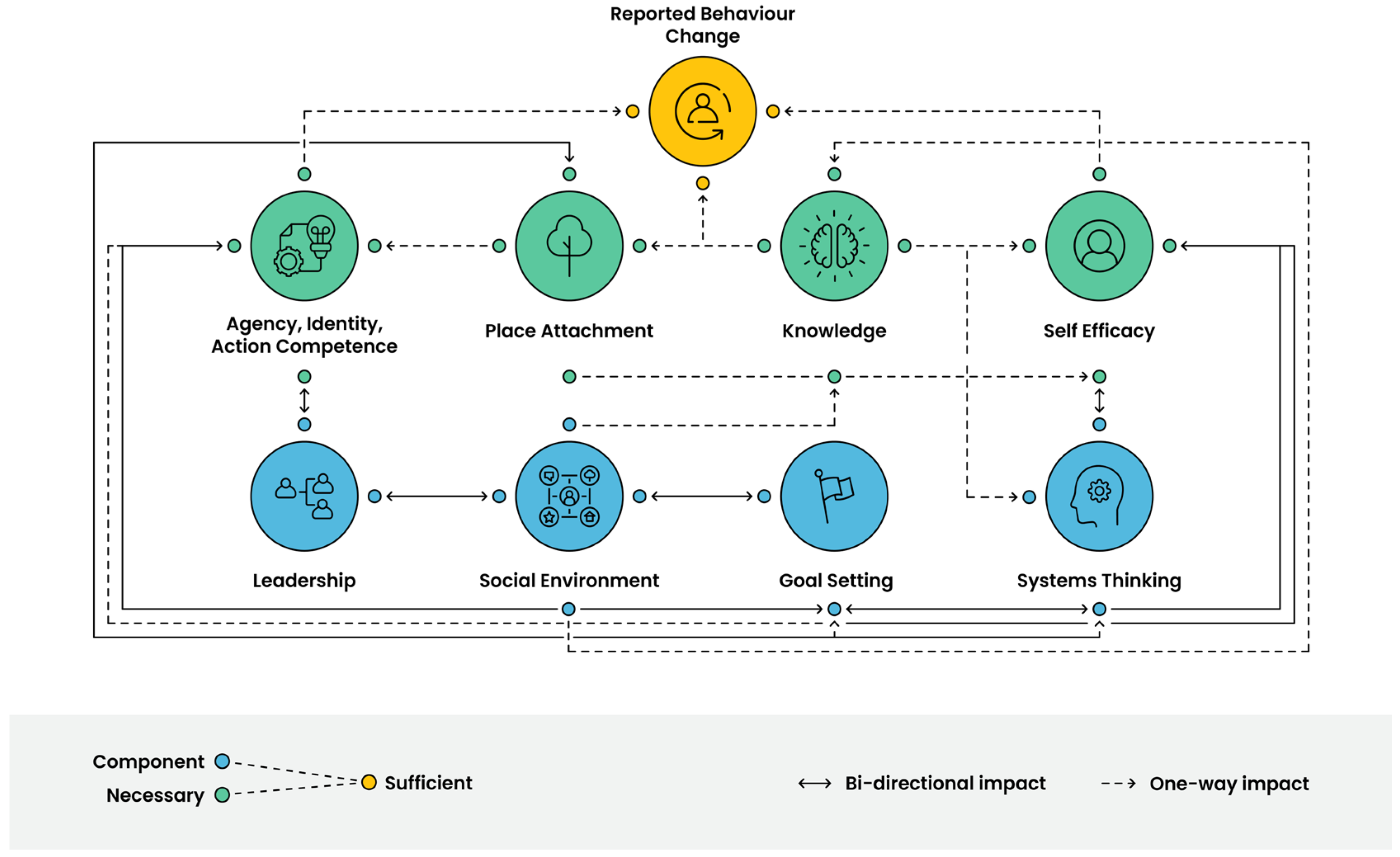

3.5. Factors Influencing Program Outcomes

3.5.1. External Factors

Social Environment

Place

Knowledge Development

Leadership

Goal Setting

3.5.2. Internal Factors

Self-Efficacy

Identity, Agency, and Action Competence

Systems Thinking

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ojala, M. Eco-anxiety. Rsa J. 2018, 164, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. Eco-anxiety, tragedy, and hope: Psychoological and spiritual dimensions of climate change. Zygon 2018, 53, 545–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léger-Goodes, T.; Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Mastine, T.; Généreux, M.; Paradis, P.-O.; Camden, C. Eco-anxiety in children: A scoping review of the mental health impacts of the awareness of climate change. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 872544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiderlin, S. Young People Just Got a Louder Voice on Climate Change—And Could Soon Be Shaping Policy; CNBC: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2022/11/23/young-people-just-became-official-climate-policy-stakeholders-at-cop27.html (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.C.; Adams, H.; Adelekan, I.; Adler, C.; Adrian, R.; Aldunce, P.; Ali, E.; Ara Begum, R.; Bednar-Friedl, B.; et al. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGII_TechnicalSummary.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Karsgaard, C.; Shultz, L. Youth Movements and Climate Change Education for Justice. 2022. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/education/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-1808 (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- UNICEF East Asia and Pacific Regional Office. It Is Getting Hot: Call for Education Systems to Respond to the Climate Crisis; UNICEF East Asia and Pacific Regional Office: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/eap/media/4596/file/It%20is%20getting%20hot:%20Call%20for%20education%20systems%20to%20respond%20to%20the%20climate%20crisis.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Willams, M.; Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience [AIDR]; Little, B.; World Vision. Our World, Our Say: Children and Young People Lead Australia’s Largest Climate and Disaster Risk Survey. Australia. 2020. Available online: https://knowledge.aidr.org.au/resources/ajem-april-2020-our-world-our-say-children-and-young-people-lead-australia-s-largest-climate-and-disaster-risk-survey/ (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Rousell, D.; Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, A. A systematic review of climate change education: Giving children and young people a ‘voice’ and a ‘hand’ in redressing climate change. Child. Geogr. 2020, 18, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter-Mackenzie, A.; Rousell, D. Education for what? Shaping the field of climate change education with children and young people as co-researchers. Child. Geogr. 2019, 17, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousell, D.; Wijesinghe, T.; Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, A.; Osborn, M. Digital media, political affect, and a youth to come: Rethinking climate change education through Deleuzian dramatisation. Educ. Rev. 2023, 75, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youth Affairs Council Victoria. Climate Change Youth Expert Advisory Group (YEAG); Youth Affairs Council Victoria: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2022; Available online: https://www.yacvic.org.au/get-involved/are-you-12-to-25/climate-change-yeag/ (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Queensland Government. Queensland Youth Strategy: Building Young Queenslanders Global Future; Report No.: 2020–21; Department of Communities, Child Safety and Disability Services: Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2021. Available online: https://www.qld.gov.au/youth/get-involved/qld-youth-strategy (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Greater Shepparton City Council. Climate Change Youth Leadership Program; Greater Shepparton City Council: Shepparton, VIC, Australia, 2022; Available online: https://greatershepparton.com.au/whats-happening/news/news-article/!/456/post/councils-seeking-expressions-of-interest-for-climate-change-youth-leadership-program (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tezlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, L.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata, R.; Castro, P.; Martins-Loução, M.A. How to promote conservation behaviours: The combined role of environmental education and commitment. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 1322–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissinger, K.; Bogner, F.X. Environmental literacy in practice: Education on tropical rainforests and climate change. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 20, 2079–2094. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10668-017-9978-9 (accessed on 20 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Ernst, J.; Blood, N.; Beery, T. Environmental action and student environmental leaders: Exploring the influence of environmental attitudes, locus of control, and sense of personal responsibility. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, J.A.; Saphir, M.; Lappé, M.; Roser-Renouf, C.; Maibach, E.W.; Leiserowitz, A.A. Evaluation of a national high school entertainment education program: The Alliance for Climate Education. Clim. Change 2014, 127, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, C.C.; Poortvliet, P.M.; Feindt, P.H. Examining the Effectiveness of Climate Change Communication with Adolescents in Vietnam: The Role of Message Congruency. Water 2020, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberger, P.; Matthes, N.; Kruse, L.; Draeger, I.; Narciss, S.; Kapp, F. Experiences with a Serious Game Introducing Basic Knowledge About Renewable Energy Technologies: A Practical Implementation in a German Secondary School. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 14, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vantamay, N. “3S Project”: A Community-Based Social Marketing Campaign for Promoting Sustainable Consumption Behavior Among Youth. J. Komun. 2019, 35, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, R.R.; Malafaia, C.; Faria, J.L.; Menezes, I. Using online tools in participatory research with adolescents to promote civic engagement and environmental mobilization: The WaterCircle (WC) project. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 1043–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemer, M.; Voorhees, C.; Dittmer, L.; Alisat, S.; Alam, N.; Sayal, R.; Bidisha, S.H.; Der Souza, A.; Lynes, J.; Metternich, A.; et al. The Youth Leading Environmental Change Project: A Mixed-Method Longitudinal Study across Six Countries. Ecopsychology 2016, 8, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senbel, M.; Ngo, V.D.; Blair, E. Social mobilization of climate change: University students conserving energy through multiple pathways for peer engagement. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, K.T.; Nils Peterson, M.; Bondell, H.D. Developing a model of climate change behavior among adolescents. Clim. Change 2018, 151, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigham, J.K.; Imbertson, P. Energy-Transition Education in a Power Systems Journey: Making the Invisible Visible and Actionable. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2020, 79, 981–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.M.; Koo, A.C.; Nasir, J.S.M.; Wong, S.Y. Playing Edcraft at Home: Gamified Online Learning for Recycling Intention during Lockdown. F1000Research 2021, 10, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, K.R.; Glasscock, S.N.; Schwertner, T.W.; Atchley, W.; Tarpley, R.S. Wildlife conservation camp: An education and recruitment pathway for high school students? Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2016, 40, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hehir, C.; Stewart, E.J.; Maher, P.T.; Ribeiro, M.A. Evaluating the impact of a youth polar expedition alumni programme on post-trip pro-environmental behaviour: A community-engaged research approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1635–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuthe, A.; Körfgen, A.; Stötter, J.; Keller, L. Strengthening their climate change literacy: A case study addressing the weaknesses in young people’s climate change awareness. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2020, 19, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, M.; Parlee, B.; Karsgaard, C. Youth engagement in climate change action: Case study on indigenous youth at COP24. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouariachi, T.; Li, C.Y.; Elving, W.J.L. Gamification Approaches for Education and Engagement on Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Searching for Best Practices. Sustainability 2020, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayal, R.; Bidisha, S.H.; Lynes, J.; Riemer, M.; Jasani, J.; Monteiro, E.; Hey, B.; De Souza, A.; Wick, S.; Eady, A. Fostering Systems Thinking for Youth Leading Environmental Change: A Multinational Exploration. Ecopsychology 2016, 8, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townrow, C.S.; Laurence, N.; Blythe, C.; Long, J.; Harré, N. The Maui’s Dolphin Challenge: Lessons From a School-Based Litter Reduction Project. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2016, 32, 288–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.C.; Chawla, L. Environmental identity formation in nonformal environmental education programs. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 978–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.C.; Carsten Conner, L.D.; Pettit, E. ‘You really see it’: Environmental identity shifts through interacting with a climate change-impacted glacier landscape. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2020, 42, 3049–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.J.; Okine, R.N.; Kershaw, J.C. Health-or Environment-Focused Text Messages as a Potential Strategy to Increase Plant-Based Eating among Young Adults: An Exploratory Study. Foods 2021, 10, 3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Hoyer, E.; Remmele, M. Collective Public Commitment: Young People on the Path to a More Sustainable Lifestyle. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehair, K.J.; Shanklin, C.W.; Brannon, L.A. Written Messages Improve Edible Food Waste Behaviors in a University Dining Facility. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooi Ting, D.; Chin Cheng, C.F. Measuring the marginal effect of pro-environmental behaviour: Guided learning and behavioural enhancement. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2017, 20, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, M.; Armel, K.C.; Hoffman, K.; Allen, L.; Bryson, S.W.; Desai, M.; Robinson, T.N. Increasing energy- and greenhouse gas-saving behaviors among adolescents: A school-based cluster-randomized controlled trial. Energy Effic. 2014, 7, 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blythe, C.; Harré, N. Encouraging transformation and action competence: A Theory of Change evaluation of a sustainability leadership program for high school students. J. Environ. Educ. 2020, 51, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, S.L.; Schroeder, B. Developing Great Lakes Literacy and Stewardship through a Nonformal Science Education Camp. J. Contemp. Water Res. Educ. 2015, 156, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, G.A.; Fischer, A.R.; Tobi, H.; van Trijp, H.C. Explicit and implicit attitude toward an emerging food technology: The case of cultured meat. Appetite 2017, 108, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, C.A.; Estrada-Mejia, C.; Rosa, J.A. Norm-focused nudges influence pro-environmental choices and moderate post-choice emotional responses. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Leifhold, C.; Hirscher, A.-L. Fashion Libraries as a Means for Sustainability Education—An Exploratory Case Study of Adolescents’ Consumer Culture. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 13, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vreede, C.; Warner, A.; Pitter, R. Facilitating Youth to Take Sustainability Actions: The Potential of Peer Education. J. Environ. Educ. 2014, 45, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, R.; Maguire, M.; Turner, S.; Arenas, F.; Guimarães, L. Ocean literacy gamified: A systematic evaluation of the effect of game elements on students’ learning experience. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, S.T.; Cruz, A.R.; Ardoin, N.M.; Durham, W.H. Community-as-pedagogy: Environmental leadership for youth in rural Costa Rica. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 1594–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayne, K.; Littrell, M.K.; Okochi, C.; Gold, A.U.; Leckey, E. Framing action in a youth climate change filmmaking program: Hope, agency, and action across scales. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 27, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, E.M.; Cordero, E. Youth science expertise, environmental identity, and agency in climate action filmmaking. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 656–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmingham, D.; Calabrese Barton, A. Putting on a green carnival: Youth taking educated action on socioscientific issues. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2014, 51, 286–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceaser, D. Our School at Blair Grocery: A case study in promoting environmental action through critical environmental education. J. Environ. Educ. 2012, 43, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oe, H.; Yamaoka, Y.; Ochiai, H. A Qualitative Assessment of Community Learning Initiatives for Environmental Awareness and Behaviour Change: Applying UNESCO Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) Framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, J.A.; Horry, R.; Skains, R.L. You and CO2: A Public Engagement Study to Engage Secondary School Students with the Issue of Climate Change. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2020, 29, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, S.R. Environmental Identity Development Through Social Interactions, Action, and Recognition. J. Environ. Educ. 2015, 46, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppert-Stroescu, M.; LeHew, M.L.A.; Connell, K.Y.H.; Armstrong, C.M. Creativity and Sustainable Fashion Apparel Consumption: The Fashion Detox. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2015, 33, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallay, E.; Furlan Brighente, M.; Flanagan, C.; Lowenstein, E. Place-based civic science—Collective environmental action and solidarity for eco-resilience. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molderez, I. How transformative learning nurtures ecological thinking. Evidence from the Students Swap Stuff project. Int. J. Sustain. High. Edu. 2021, 22, 635–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gibson, H.J. Long-term impact of study abroad on sustainability-related attitudes and behaviors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Li, H. Environmental education, knowledge, and high school students’ intention toward separation of solid waste on campus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, C.J.; Guy, E.; Al-Baldawi, Z.; McVean, L.; Sargent, S.; O’Sullivan, T. “I believe this team will change how society views youth in disasters”: The EnRiCH Youth Research Team: A youth-led community-based disaster risk reduction program in Ottawa, Canada. Can. J. Public Health 2021, 112, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemer, M.; Lynes, J.; Hickman, G. A model for developing and assessing youth-based environmental engagement programmes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2014, 20, 552–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. Inclusion with nature: The psychology of human-nature relations. In Psychology of Sustainable Development; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Schultz, P.; Berenguer, J.; Corral-Verdugo, V.; Tankha, G. General Ecological Behavior Scale—Expanded Version. Eur. Psychol. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, C.D. Reshaping our world: Collaborating with children for community-based climate change action. Action Res. 2019, 17, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synofzik, M.; Vosgerau, G.; Voss, M. The experience of agency: An interplay between prediction and postdiction. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.; Mills, S.B. Moving forward on competence in sustainability research and problem solving. Environment 2011, 53, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A. Climate change education and research: Possibilities and potentials versus problems and perils? Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 767–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novick, R. Empowering a Movement: The Influence of Climate Change Education on the Rise in Youth Climate Activism in the United States. In Proceedings of the AGU Fall Meeting, New Orleans, LA, USA, 13–17 December 2021; p. ED55H-02. Available online: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2021AGUFMED55H..02N (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Etchanchu, H.; Kassardjian, E.; Jahier Lecorre, P. How to Communicate Effectively to Foster Climate Action: The Role of Emotions, Science Education, Social Norms, and Youth Movements. USA. 2021. Available online: https://cdurable.info/IMG/pdf/icf-next-climate-communications-report.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Hornsey, M.J.; Fielding, K.S. Understanding (and reducing) inaction on climate change. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2020, 14, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskreis-Winkler, L.; Milkman, K.L.; Gromet, D.M.; Duckworth, A.L. A large-scale field experiment shows giving advice improves academic outcomes for the advisor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 14808–14810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arches, J. The role of groupwork in social action projects with youth. Groupwork 2012, 22, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowasch, M.; Cruz, J.P.; Reis, P.; Gericke, N.; Kicker, K. Climate youth activism initiatives: Motivations and aims, and the potential to integrate climate activism into ESD and transformative learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilder, C.; Collin, P. The role of youth-led activist organisations for contemporary climate activism: The case of the Australian Youth Climate Coalition. J. Youth Stud. 2022, 25, 793–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etmanski, C.; Bishop, K.; Page, M.B. Adult Learning Through Collaborative Leadership: New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, Number 156; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Klöckner, C.A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Graham Smith, L.D.; Weiler, B. Testing the dimensionality of place attachment and its relationships with place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviours: A structural equation modelling approach. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

| Research Methods | No. of Articles | % of Articles |

|---|---|---|

| Interviews | 18 | 37.5% |

| Focus Groups | 4 | 8% |

| Observation | 6 | 12.5% |

| Surveys | 29 | 60% |

| Document analysis | 5 | 10% |

| Blogs/posts | 2 | 4% |

| Group Discussion | 1 | 2% |

| Item analysis | 1 | 2% |

| Research Design | No. of Articles | % of Articles * | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quasi-experiment | 7 | 15% | Barata et al. [18]; Bissinger and Bogner [19]; Ernst et al. [20]; Flora et al. [21]; Ngo et al. [22]; Spangenberger et al. [23]; Vanatamay [24] |

| Mixed-methods quasi-experiment designs | 4 | 8% | Marques et al. [25]; Riemer et al. [26]; Senbel et al. [27]; Stevenson et al. [28] |

| Case study designs | 11 | 23% | Brigham and Imbertson [29]; Cheng et al. [30]; Griffin et al. [31]; Hehir et al. [32]; Kuthe et al. [33]; Mackay et al. [34]; Ouariachi et al. [35]; Sayal et al. [36]; Townrow et al. [37]; Williams et al. [38]; Young et al. [39] |

| Intervention study | 3 | 6% | Lim et al. [40]; Lindemann-Matthies et al. [41]; Whitehair et al. [42] |

| Ordered probit | 1 | 2% | Hooi Ting et al. [43] |

| Randomised control trial | 1 | 2% | Cornelius et al. [44] |

| Participatory, utilization-focused evaluation | 1 | 2% | Blythe et al. [45] |

| Impact evaluation | 1 | 2% | Dann and Schroeder et al. [46] |

| Between subjects experiment | 2 | 4% | Bekker et al. [47]; Trujillo et al. [48] |

| Mixed methods | 6 | 12% | Becker-Leifhold and Hirscher [49]; de Vreede et al. [50]; Leitão, [51]; Selby et al. [52]; Tanye et al. [53]; Walsh and Cordero [54] |

| Ethnography | 3 | 6% | Birmingham and Calabrese [55]; Ceaser et al. [56]; Oe et al. [57] |

| Pilot intervention | 1 | 2% | Rudd et al. [58] |

| Critical sociocultural analysis | 1 | 2% | Stapleton [59] |

| Exploratory content analysis | 2 | 4% | Ruppert-Stroescu et al. [60]; Gallay et al. [61] |

| Participatory action research | 1 | 2% | Molderez [62] |

| Interpretivist approach | 1 | 2% | Zhang et al. [63] |

| Cross-sectional survey | 1 | 2% | Liao and Li [64] |

| Qualitative description | 1 | 2% | Pickering et al. [65] |

| Discipline | Theory/Framework/Model | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Environment | Place-based or attachment theories | Birmingham and Calabrese, [55]; Dann et al. [46] |

| Environmental Identity theory (Clayton) | Young et al. [39]; Walsh and Cordero [54] | |

| Psychology | Social Identity theory | Hehir et al. [32] |

| Message Representation and Construal Level Theory (CLT) | Ngo et al. [22] | |

| Social Capital Theory | Cornelius et al. [44]; Mackay et al. [34] | |

| Theory of Change | Blythe and Harre [45]; Brigham and Imbertson [29] | |

| Social Environmental Identity | Stapleton [59] | |

| Theory of Commitment | Barata et al. [18] | |

| Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) | Hooi Ting and Chin Cheng [43]; Molderez [62]; Liao and Li [64]; Lim et al. [40] | |

| Norm activation theory | Hooi Ting and Chin Cheng [43] | |

| Psycho-social framework | Townrow et al. [37]; Ernst et al. [20] | |

| Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion | Whitehair et al. [42] | |

| Personal and social norm approach | Trujillo et al. [48] | |

| Social Sciences | Community-Based Social Marketing Approach | Vantamay [24] |

| Critical Theory | Ceaser et al. [56] | |

| Social Practice Theory | Williams and Chawla [38] | |

| Education | Climate Change Education (CCE) | Rudd et al. [58] |

| Environmental Literacy | Bissinger and Bogner [19] | |

| Transformative Learning | Blythe and Harre [45] | |

| Theory of Engagement | Riemer et al. [26] | |

| Pedagogical Learning Theory | Becker-Leifhold and Hirscher [49] | |

| Community-as-pedagogy framework | Selby et al. [52] | |

| 21st Century Skills Framework | Pickering et al. [65] | |

| ESD framework | Oe et al. [57] | |

| Place-based civic science pedagogy model | Gallay et al. [61] | |

| Behavioral Economics | Choice architecture | Trujillo et al. [48] |

| Public Health | Health Belief Model | Lim et al. [40] |

| Quantitative Outcome Measure | Authors |

|---|---|

| Place | |

| Place attachment | Dann and Schroeder [46] |

| Stewardship | Dann and Schroeder [46] |

| Self | |

| Agency | Riemer et al. [26]; Walsh and Cordero et al. [54] |

| Nature in self | Hehir et al. [32] |

| Self-efficacy | Cornelius et al. [44] |

| Self-perceived attitudes | Dann and Schroeder [46] |

| Social identity | Hehir et al. [32] |

| Behavior | |

| Climate friendly behavior | Kuthe et al. [33]; Lim et al. [40] |

| Energy saving behavior | Cornelius et al. [44] |

| Environmental action | Barata et al. [18]; Flora et al. [21]; Hooi Ting [43]; Riemer et al. [26]; Stevenson et al. [28] |

| General ecological behavior | Hehir et al. [32]; Trujillo et al. [48] |

| Attitudes, intentions and norms | |

| Attitudes towards pro-environmental behavior | Vantamay [24]; Ernst et al. [20] |

| Behavioral intentions | Bissinger and Bogner [19]; Dann and Schroeder [46]; Bissinger and Bogner [19]; de Vreede et al. [50]; Lim et al. [40] |

| Concern for the environment | de Vreede [50] |

| Importance of environmental sustainability | Cornelius et al. [44] |

| Subjective norms | Vantamay [24] |

| Knowledge | |

| Knowledge | Bissinger and Bogner [19]; Cornelius et al. [44]; Flora et al. [21]; Griffin et al.; Kuthe et al. [33]; Leitão et al. [51]; Stevenson et al. [28] |

| Qualitative Elements | Authors |

|---|---|

| Behavior | Lim et al. [40]; Lindemann-Matthies et al. [41]; Oe et al. [57]; Ouariachi et al. [35]; Trujillo et al. [48]; Zhang and Gibson [63] |

| Critical thinking | Rudd et al. [58] |

| Ecological and systems thinking | Molderez [62] |

| Environmental action | Ceaser [56]; Gallay et al. [61] |

| Environmental identity | Stapleton et al. [59]; Williams and Chawla [38] |

| Intention | Lim et al. [40]; Cheng et al. [30] |

| Leadership skills | Mackay et al. [34] |

| Sustainability-related attitudes | Oe et al., 2022; Zhang and Gibson, 2021; Oe et al., 2022 |

| Systems thinking | Sayal et al. [36]; Young et al. [39] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hohenhaus, M.; Boddy, J.; Rutherford, S.; Roiko, A.; Hennessey, N. Engaging Young People in Climate Change Action: A Scoping Review of Sustainability Programs. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054259

Hohenhaus M, Boddy J, Rutherford S, Roiko A, Hennessey N. Engaging Young People in Climate Change Action: A Scoping Review of Sustainability Programs. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054259

Chicago/Turabian StyleHohenhaus, Madeleine, Jennifer Boddy, Shannon Rutherford, Anne Roiko, and Natasha Hennessey. 2023. "Engaging Young People in Climate Change Action: A Scoping Review of Sustainability Programs" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054259

APA StyleHohenhaus, M., Boddy, J., Rutherford, S., Roiko, A., & Hennessey, N. (2023). Engaging Young People in Climate Change Action: A Scoping Review of Sustainability Programs. Sustainability, 15(5), 4259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054259