Abstract

The expansion of financial markets has enabled individuals to invest in a variety of securities and financial instruments. Consequently, behavioral finance has shed light on the characteristics and psychological processes that influence the investment intentions and decisions of investors. We performed a systematic review of the recent literature on the key elements that influence the behavioral intentions and investment decisions of individual investors. In combination with bibliometric and weight analysis, this review aims to propose a comprehensive approach to present quantitative and qualitative analyses of the rising elements influencing investors’ intentions and behaviors in financial investment products. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement, this work comprises a review of 28 articles published in Web of Science and Scopus databases between 2016 and 2021. The findings identify six underlying themes of investor behavior determined using content: (1) personal factors, (2) social factors, (3) market information, (4) firm-specific factors, (5) product-related factors, and (6) demography. The future research agenda is highlighted based on the Theories, Constructs, Contexts, and Methods framework. The findings provide insights for both theoretical and practical application for corporations, financial institutions, and policy makers in understanding investors’ behavior so as to strengthen the financial industry and economy.

1. Introduction

Investors normally generate returns by allocating capital to equity or debt investments. In light of recent market occurrences, investors may consider whether they should revise their investment portfolios. In an uncertain and unpredictable environment, investors rely on trial and error or old rules of thumb to make decisions. In reality, however, cognitive and emotional aspects are included while evaluating investment alternatives, which can eliminate logical conduct in the decision making process. Financial market expansion has created opportunities for individuals to invest in a variety of financial instruments. As such, the discipline of behavioral finance has enriched the understanding of individual investors’ behaviors by elucidating the individual attributes and psychological processes that influence their investment intentions and subsequent decisions [1].

The classical economic theory assumes that individuals act rationally as they aim to maximize their wealth by adhering to the basic financial rules and considering all available information when making investment decisions. They usually exercise fundamental analysis, technical analysis, and judgment when performing investment analysis [2]. Investment decisions are generally influenced by the market information structure and characteristics. Meanwhile, individual risk tolerance determines the degree of risk that people are willing to take. Regardless of how well-informed an individual is and the amount of research they have conducted on investment products before investing, they still behave irrationally due to the fear of future loss [3].

Contrary to the conventional economic theory, behavioral economics displays a variety of factors, including market features, individual risk profiles, and accounting information, which can impact individual financial decisions [3]. Researchers in behavioral economics have discovered repeated patterns of irrationality, inconsistency, and incompetence in individual investment decisions, particularly under risk and uncertainty conditions. In short, an individual’s investment decisions are influenced by both rational and irrational causes. It is critical to understand human behavior and decision making from a financial standpoint and investigate the factors influencing investment intention based on the investors’ perspectives.

Previous studies have examined investor behavior in the stock market [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20], mutual funds [21,22,23,24,25,26], bonds [27,28,29,30], and investment for retirement planning [31]. In terms of the stock market, studies have been conducted in the context of India [6,7,8,11,12], Pakistan [16,17,18,19], Saudi Arabia [5,14], Vietnam [13], Taiwan [9], and Malaysia [4]. Meanwhile, in terms of mutual funds, studies have been performed in the context of Indonesia [21], India [24,25,26], and Malaysia [22,23]. Studies on bonds have only been undertaken in Indonesia [27,28], UAE [29], and Pakistan [30], whereas research on retirement planning has been conducted in the context of Ireland and Turkey [31]. Moreover, some of the studies have focused on Shariah compliance [21,27,29,30] and green investment [6]. For the case of Shariah compliance, studies have been performed on Shariah equity mutual funds in Indonesia [21], Sukuk in the context of UAE [29], Indonesia [27], and Pakistan [30]. Furthermore, while several investor behavior studies have been conducted in terms of investment behavior [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,23,24,26,29], there are also studies on investment intention [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,21,22,25,27,28,30,31] to represent behavioral decisions. According to Ajzen [32], behavioral intention influences behavioral performance. The more devoted a person is to engaging in a particular behavior, the more likely it is that they will act on it. Thus, intention can be used to predict behavior.

Traditional literature reviews have various flaws, including being rarely thorough, having a high risk of reviewers’ bias, and rarely considering the differences in study quality. A systematic literature review (SLR) is an approach that rigorously reviews current material [33]. It is a method for locating, selecting, and critically evaluating prior works on a specific issue. A systematic literature review process requires a prior procedure or plan. SLR is a well-organized and transparent system in which the search is performed through various reputable databases. A systematic review includes details on the review process (such as keywords used and articles chosen) that can be adopted by other researchers to replicate and verify their findings. This methodical search process enables academicians to identify solutions to specific problems [34]. Based on this information, we developed a holistic perspective on each driver of investment decision making based on previous findings to answer the formulated research questions.

Although there are some studies that have attempted to systematically review the issue of investor behavior, these studies have not yet presented a complete view of financial instruments, as they have focused only on specific instruments, such as the stock market [35], socially responsible investments (SRI) [36], crowdfunding [37], and cryptocurrencies [38]. Kumar and Goyal [35] investigated the effects of cognitive biases on investors in the stock market. Meanwhile, Zahera and Bansal [39] identified several biases and provided solutions to minimize the effect of biases in decision making. Meanwhile, Ferrati and Muffatto [40] summarized and organized the current knowledge about the valuation criteria used by equity investors when evaluating a venture proposal. Hassan [41], despite the fact that their analysis covers a wide range of products, solely examines Islamic investments. The novelty of this study is that it examines all aspects of investment instruments (such as bonds, stocks, mutual funds, etc.), regardless of whether it is a conventional or Islamic investment, which fills the literature gap on general investment worldwide. In addition, in this study, we used several innovative approaches combining different methodologies, such as bibliometric analysis in exploring large volumes of scientific data at an initial stage, weight analysis in selecting the best and most promising predictors, as well as the Theories, Constructs, Contexts, and Methods (TCCM) as a framework in establishing a future research agenda.

In summary, this study aims to fill the gaps in the previous literature by assessing the influence of various key consumer behavior variables on investors’ investment intentions. The review is guided by a central research question: what are the predictors of investment intention and investment behavior among individual investors? The goal of this study is to illuminate new behavioral finance trends. Therefore, this study aims to identify and describe the predictors of investment intention and behavior among individual investors based on the previous literature. By systematically reviewing the literature and conducting weighted and content analyses on investment intention and behavior, this study intends to contribute to the existing body of knowledge. Understanding the factors influencing adoption intentions and actual usage behavior helps to set the direction for future research among academicians. This study also provides practical recommendations to practitioners who wish to build techniques to boost investors’ engagement in financial planning and investment strategies based on a detailed assessment of the factors influencing investment intentions and behavior. This paper is organized into several sections. Section 2 describes the process, while Section 3 summarizes the findings, which cover the descriptive, weighted, and content analyses. Section 4 examines knowledge gaps and possible research topics. Finally, Section 5 concludes the study.

2. Methodology

2.1. The Review Protocol—PRISMA

This study was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [42]. According to [43], it offers three unique advantages: (1) it defines a clear research question that allows the thematic research of the system, (2) it identifies inclusion and exclusion criteria, and (3) it attempts to perform verification. The SLR process began with the formulation of appropriate research questions for the review, guided by PRISMA. Next, a document search technique was devised and performed in three stages, namely identification, screening, and eligibility. Finally, we described the extraction of data for the review, along with the analyses and validation of the extracted data.

Based on the selected articles, we performed a meta-literature review incorporating bibliometric (quantitative) and content (qualitative) approaches. Meta-analysis is described as "the examination of examinations" [44]. Using bibliometric citation analysis to conduct a meta-literature review is a relatively new technique [45]. This meta-analysis method is distinct from the standard statistical meta-analysis because it is based on the regression analysis of previous empirical investigations [46,47,48,49,50]. Hence, it is commonly employed in the recent literature. Bibliometric citation analysis and keyword analysis were performed in this study. The bibliometric analysis was conducted using two software programs, namely Harzing’s POP and VOSviewer.

We used Scopus and Web of Science (WoS), two of the most well-known indexed databases, to obtain behavioral investment-related articles for this review. Both databases are regarded as the most valuable citation indexing systems [51]. Clarivate Web of Science was selected as the database for document collection because it is a very comprehensive bibliographic data source [51,52,53]; it is considered the most reliable database for publications and citations in the world [54]. Meanwhile, Scopus has established itself as a trustworthy source of comprehensive bibliographic data and has even outperformed WoS in some areas [55,56]. Scopus covers various topics, including science, technology, medicine, social sciences, arts, and humanities [51].

2.2. Formulation of Research Questions

The formulation of the research question for this study was based on PICo, which stands for population, interventions, comparators, and outcomes. PICo is a tool that assists authors in developing relevant research questions for a review [57]. Hence, we incorporated the three primary components in the review, namely individual or retail investor (population), determinants of investment intention and investment behavior (interest), and financial products (context). The context of financial products was limited to mutual funds, stocks, and bonds. The three components guided us to formulate a key research question: what are the predictors of investment intention and investment behavior among individual investors?

2.3. Systematic Searching Strategies

The systematic searching strategy procedure involves three main steps, namely identification, screening, and eligibility.

2.3.1. Identification

Identification is a procedure that involves searching for synonyms, related terms, and variations in the study’s primary keywords, which are investment intention, investment behavior, and individual investors. It increases the number of database options to search for additional relevant articles for the review. The keywords were determined using Okoli’s (2015) [58] research question and were identified using a variety of sources, including an online thesaurus, keywords from previous studies, keywords suggested by Scopus, and keywords proposed by experts. We upgraded the existing keywords for WoS and Scopus before developing a search string (using Boolean operators, phrase searching, truncation, wild card, and field code functions), as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Databases and search strings.

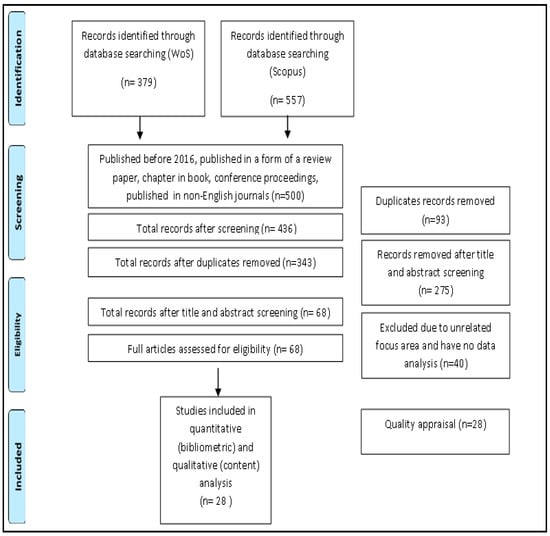

Initially, 936 publications were retrieved from 2016 to May 2021 across the two selected databases, of which 379 were from WoS and 557 articles were from Scopus. All retrieved articles were recorded in an Excel sheet to screen for duplicated materials before exporting them to the “Mendeley“ software for article management purposes.

2.3.2. Screening

We screened all 936 articles using automated criteria selection based on the database’s sorting function. Since it is nearly impossible to review all the previously published articles, [58] recommended a review period. Based on the findings of the database search, the number of studies connected to behavioral investment intention has increased dramatically since the year 2000. Meanwhile, individual investor behavior research began to acquire traction in both the WoS and Scopus databases in 2016. In the meantime, the search was limited to May 2021 based on the search process that began in May 2021. On this basis, the period between May 2016 and May 2021 was selected as one of the inclusion criteria. The search was limited to the last five years in order to capture the most recent work and identify the most current developments in this ever-evolving sector. As for the time frame, five years is sufficient to observe the pattern of research and related publications [59]. Moreover, we did not include the term "individual investors" in the search string because we did not wish to limit the articles to individual or institutional investors. To avoid ambiguities, only research with actual data published in English was included in the review.

In this process, a total of 93 duplicated items and 500 articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were removed from the review process (Table 2). The remaining 343 articles were then subjected to the third step of determining eligibility.

Table 2.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.3.3. Eligibility

The retrieved articles were manually checked during the eligibility step to ensure that all of the remaining articles (after the screening procedure) fitted the requirements. The manual check was performed by reading the titles and abstracts of the articles. A total of 297 articles were eliminated because they focused on investment performance instead of investor predictors and determinants of investment decision making. Therefore, conceptual or review publications without statistical data were disqualified. Finally, only 28 items were utilized in this review.

2.4. Data Extraction

Based on Figure 1, the 28 articles that were finalized were examined and data were extracted. We carefully reviewed each of the 28 publications by paying special attention to the abstracts, findings, and discussions. Relevant data were retrieved based on the research questions, where studies that answered these questions were selected and organized in a table. The bibliometric and weight analyses were carried out, followed by identifying the themes and sub-themes using patterns, grouping, and counting [60].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study (adapted by Moher et al. [42]).

We utilized this method to construct themes to explore inconsistencies, thoughts, puzzles, or other ideas on data interpretation, to identify the updated themes and sub-themes. The developed themes and sub-themes were examined through a qualitative technique by an expert and a community development specialist. Lastly, six primary themes and 17 sub-themes were assigned by the experts. Both experts agreed that the chosen themes and sub-themes corresponded with the findings from the review.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Bibliometric Analysis

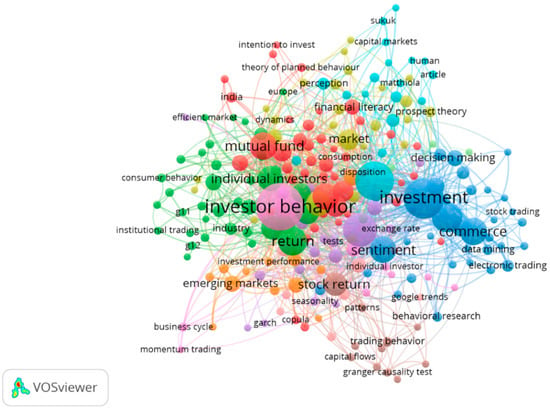

Using the VOSviewer application [61], as illustrated in Figure 2, we discovered that investor behavior, stock market, investment, financial market, commerce, and behavioral finance were frequently associated with investors’ behavioral intention and decision making. The color, circle size, font size, and thickness of connecting lines represented the relationships with other keywords. The keywords mirrored the main themes and sub-themes identified throughout the systematic literature review procedure.

Figure 2.

Network visualization map of the keywords in individual investors’ behavioral intention.

Based on the review, multiple theories were used in investment intention and behavior research to determine an individual’s behavioral intention and actual behavior (Table 3). The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) was most preferred in behavioral intention research. Most of the studies employed an expanded version of this theory that considered additional factors influencing the intention or actual behavior. Another preferred theory was the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). Overall, one article each employed the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), Prospect Theory, and Portfolio Theory to examine the factors affecting investors’ decision making.

Table 3.

Theories used in the research on investor behavioral intention and decision making.

Of the collated articles, eight studies were conducted in India, five in Pakistan, three in Malaysia, three in Indonesia, two in Saudi Arabia, and two in Vietnam. Meanwhile, one study each was conducted in Italy, Taiwan, the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, Ireland, Mainland China, and Hong Kong (Table 4). In terms of the study focus, 16 articles concentrated on intention, 7 on actual behavior, and 5 on the investor decision making process. The majority of the studies focused on the stock market (n = 17). Only six studies were devoted to mutual funds, four to bonds, and one to investment retirement planning. A total of 24 articles were conventional studies, while 4 studied Islamic investment. The majority of them employed quantitative analyses. Only one article employed a mixed-method research design.

Table 4.

The study contexts in the research on investor behavioral intention and decision making.

On the other hand, the most commonly used analytical methods included structural equation modeling (SEM) and partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) statistical methods (Table 5). Meanwhile, factor analysis and regression analysis were the two other most popular statistical methods used for analysis. Due to its limitation regarding categorical data, only a few studies applied logistic regression. Since SEM is a combination of factor analysis and regression analysis, it could be an appropriate technique for future studies in the field of the behavioral intention of investors to analyze structural relationships.

Table 5.

Methods of analysis applied in the research on investor behavioral intention and decision making.

3.2. Weight Analysis

Weight analysis measures the impact of an independent variable on an outcome (dependent variable). This method can be used to study the predictive potential of an independent variable in a relationship under investigation [62]. Table 6 provides a brief overview of the correlations in the 28 analyzed studies. It includes the number of significant and nonsignificant associations, the total number of previously investigated links between dependent and independent variables, and the weight assigned to each of these interactions.

Table 6.

Results of weight analysis.

Weight analysis was performed by dividing the number of significant relationships by the total number of the analyzed relationships [62,63,64]. “Well-used” (examined more than five times) and “experimental” (examined less than five times) are the two types of predictors. A “well-used” predictor is considered the “best” predictor if its weight exceeds 0.8. Meanwhile, an “experimental” predictor is considered a promising predictor if its weight is one (1) [62].

Based on the studies, the “best” predictors that were identified included attitude, subjective norms, PBC, heuristics, emotion, financial literacy, reputation, product features, and demographic factors. These best predictors in the weight analysis were identified to be the most examined sub-themes in terms of intention, actual behavior, and decision making. Attitude and subjective norms of financial behavior were also identified as strong predictors in other contexts, such as mobile banking [65,66], entrepreneurial intention [67,68], and health-related behavior [69,70]. The importance of personality traits was also highlighted by Lissitsa and Kol [71] as one of the most critical factors for purchase intention. Moreover, an increase in financial literacy can lead to insurance purchasing, as it also significantly and positively impacts the behavioral intention.

3.3. Content Analysis

We discovered that numerous variables comprised various pre-existing codes that were almost certainly the same item. Some constructs were synonyms and were merged into a single phrase (i.e., financial literacy, financial knowledge, investment literacy, and technical financial knowledge were considered jointly as a single construct of financial literacy). Following the grouping process, the pre-existing set of codes was finalized and blended with some newly emerged codes, leading to a final number of 41 codes.

Similar or related codes were grouped into four primary groupings for intention studies, six for behavior studies, and four for decision making studies. Subsequently, we assessed all 14 data groups to confirm the sub-groups. Then, the accuracy of the themes was reassessed in the next stage. We also ensured that all of the developed main themes and sub-themes were appropriate for data representation. As such, the theme of personal factors was divided into two categories during this process, namely psychological and cognitive factors. Finally, the studies had 6 main themes and 17 sub-themes.

Table 7 summarizes all determinants of investors’ behavioral intention, resulting in six categories. The dominant themes were the psychological and social factors, consisting of 25 and 18 studies, respectively. Meanwhile, 10 and 7 articles focused on cognitive and product-related aspects, respectively. The relatively less explored themes in the investor behavioral intention literature were the firm-specific and financial development factors, with five and one articles each. The following subsections discuss each theme in detail.

Table 7.

The themes and the sub-themes of investors’ behavior and decision making.

In addition to the direct impact of the aforementioned variables on investment intention, a number of studies have revealed the mediating and moderating mechanisms between the variables and intention. Seven studies were related to the stock market, while only one study was related to Sukuk (see Table 8). In the mediating analysis, two studies concluded that attitude is an effective mediator between previous behavior and intention [7] and between financial knowledge and investment intention [8]. Meanwhile, two studies examined perceived risk as a mediator between psychological factors, social factors, and investment decisions [16] and between brand equity and investment intention [10]. Three of the five studies that analyzed the moderating role indicated a positive effect of moderating variables, such as the effect of religious aspects on the social influence–intention relationship [30] and financial self-efficacy (FSE) on the personality traits–intention relationship [8]. Individuals’ personality and perceptive factors towards stock investment intention were found to be moderated by gender, age, and experience [9].

Table 8.

Mediating and moderating variables.

3.3.1. Personal Factors

The review revealed that the personal factors could further be divided into two major sub-themes, psychological and cognitive factors. The first sub-theme of psychological factors is attitude. Individual attitudes were associated with investment behavior in 11 of the studies. The majority of the studies applied the TPB as a model, except Sumiati et al. [21] and Raut et al. [6], who tested the TRA. Most of the studies highlighted the direct effects of attitude, except Raut [7], Akhtar and Das [8], Ashidiqi and Arundina [27], and Sivaramakrishnan et al. [12]. Individuals with a positive attitude toward a behavior are more likely to engage in it [8,31], while negative attitudes are the result of a set of beliefs from outcomes that are both extremely unfavorable and unlikely [72]. Consequently, an individual’s attitude toward a particular behavior is a good predictor of their intent to engage in this behavior [8].

A positive attitude toward investing improves the intention to invest in Shariah-compliant equity mutual funds among Indonesian college students because they believe that doing so will be rewarding, useful, and beneficial [21]. The findings were consistent with several other studies, where attitude influenced university students’ inclination to invest in a pension fund in Italy [31] and Sukuk in Indonesia [27]. Moreover, Raut [7] also discovered that attitude can also serve as a significant mediating variable between past behavior and intention. Investors frequently conduct a biased search of their memory for previously acquired experiences to support their attitude and influence their intention regarding a current investment decision. The mediating role of attitude between financial knowledge and intention was also evidenced in past studies [8].

Secondly, PBC, or people’s perception to perform a given behavior, was found to be a positive predictor of investment intention in the stock market [7,8,9,11], retirement [31], and Sukuk [27]. Contrarily, Dewi and Tamara [28] discovered a negative effect of PBC on the intention but a positive effect on the behavior of employees to invest in retail bond products. However, the findings were questionable, as the theories and previous studies proved that intention has a similar effect to that of behavior. Akhtar and Das [8], who tested the direct and indirect effects of PBC, also tested FSE to capture PBC and reported that FSE has a significant mediating and moderating effect between personality traits and intention.

Thirdly, moral norms, or one’s perception of the moral correctness or incorrectness of performing a behavior, were added as a new component of TRA by Raut et al. [6]. Moral norms are defined as one’s own beliefs regarding the obligation to perform or refuse to execute a particular behavior including intrinsic motivation. The authors indicated that it could substantially impact investors’ intentions toward SRI in India. Similarly, Khan et al. [30] showed that intrinsic motivation carries considerable beneficial effects on investors’ intention to participate in Sukuk.

The next sub-theme, personality traits, represents inherent features of an individual; thus, they may operate as antecedents to perceptual constructs in predicting an individual’s behavioral intention. For instance, a cheerful individual may find stock investment pleasurable [9,25]. Meanwhile, risk tolerance is a personality trait that could affect investors’ investment behavior. Lim et al. [1] studied the differences in investment decisions and behaviors between high- and low-uncertainty-avoidance investors. Based on their study, investors with low uncertainty avoidance demonstrated high risk tolerance and confusion or ambiguity about the success of their investment (i.e., will it yield profit or loss?). On the other hand, individuals with risk tolerance tend to take on investments before fully understanding the financial risks [73]. This positive high risk tolerance–intention relationship has been evidenced in the stock markets of Saudi Arabia [5,14] and Malaysia [4], with the exception of the unit trust in Malaysia [23]. According to Akhtar and Das [8], individuals with a high preference for innovation and risk-taking proclivity are more likely to invest in financial markets, especially when they have a high level of confidence in their ability to do so. As such, Cao et al. [13] analyzed personality traits such as loss aversion, regret aversion, and mental accounting to establish a substantial impact on investment decision making in Vietnam. Meanwhile, Lai [9] demonstrated the big five taxonomies, namely openness, extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism, to positively influence stock investment intention.

Of the available literature, only two studies covered the fifth sub-theme, past behavior. Mak and Ip [20] claimed that individual investors in Mainland China and Hong Kong were driven by experience or an investment assessment process when making investment decisions. Contrarily, Raut [7] discovered that previous investment experience had no bearing on the investment intentions of Indian stock market investors. However, the relationship between past behavior and investment intention becomes significant when it has been mediated by attitude.

The sixth sub-theme is compatibility. According to Khan et al. [30], individuals choose and use products or services in line with their lifestyles and beliefs, thus increasing their intention to invest in Sukuk. Since Sukuk is an Islamic financial instrument, Muslims in the Muslim-majority nations, such as Pakistan, believe that it is compatible with their way of life, evidenced by a strong compatibility–investment intention relationship.

Heuristics is the seventh sub-theme. Previous studies indicated that heuristics helps investors to make decisions because it is a strategy that does not consider all information to make a faster, cheaper, and/or more accurate decision compared to a more complicated method [74]. Representativeness, overconfidence, anchoring, gambling, and availability bias are among the heuristic variables that can positively impact investment decision making [13,19]. For instance, heuristics played a significant role in making investment decisions in Vietnam [13]. The study outcome demonstrated that heuristic biases influence investors to act irrationally and make trading errors. Hence, heuristics can also negatively impact an individual’s investing decisions. Psychologically, investors cannot make better investment decisions due to heuristics.

The final sub-theme under the psychological theme is emotion. Angry investors may be able to obtain more clues about the situation because they are more aware of what is taking place, are more willing to consider other aspects, and have a better understanding of the situation than normal investors. Additionally, fear can also help investors to make smarter investments. Investors who are afraid are more alert to the risks and uncertainties of investment; hence, they would rarely invest in risky or unknown stocks. Fear also allows investors to be more analytical of their decisions. Investors who are in a good mood can make balanced and precise decisions, enabling them to take risks with good outcomes. When in a good mood, they are able to have a realistic and positive view of the situation. Hence, anger, fear, and a positive mood could positively influence investors’ decision making. Meanwhile, stress, social interaction, and herding can impair their decision making. Of the six variables studied, anger was identified to bear the greatest impact on Pakistani investors’ stock market selections [16].

On the other hand, the second major sub-theme under the personal factors is the cognitive factors related to the individuals’ financial literacy. Financial literacy can be categorized into subjective and objective knowledge [75,76]. The term “subjective knowledge” refers to the self-assessed financial confidence (i.e., how each individual perceives their knowledge of finance). Meanwhile, objective knowledge is the fundamental financial knowledge based on an individual’s understanding of finance and economics concepts, such as inflation, stock markets, savings, credit, and insurance. In short, both subjective and objective financial literacy are strong predictors of intention [4,6,7,22]. However, only objective financial literacy was proven to affect an individual’s investment intentions in the Indian stock market [8,12]. The authors claimed that objective financial literacy is the actual knowledge possessed by an individual that enables prospective investors to generate more external-based thoughts in uncertain financial market conditions. Contrarily, Shehata et al. [5] reported that subjective knowledge has a greater influence than objective knowledge on stock investment intention in Saudi Arabia. Meanwhile, Kaur and Kaushik [26] added that both subjective and objective financial literacy can positively affect mutual fund investment intention in India. In the context of pension funds among Italian students, Bongini and Cucinelli [31] discovered that objective financial literacy (money management and pension knowledge) and other TPB predictors are positively associated with their intention to invest.

3.3.2. Social Factors

Previous studies examined social factors in the context of social influence and religiosity. In stock market decision making, investors were influenced by their social influences in Malaysia [4], Saudi Arabia [14], India [7,8,12], Pakistan [16,17], Vietnam [13], and Taiwan [9]. Similarly, social influences were also discovered in Sukuk investments in Pakistan [30] and Indonesia [27], and in Islamic mutual funds [21] and retail bonds [28] in Indonesia, while not present in retirement planning in Italy [31]. Khawaja and Alharbi [14] investigated the impacts of social influence in terms of advocate recommendations, such as advice or recommendations from other stockholders, brokers, friends, and family members, that could significantly affect the investor behavior in the Saudi investment opportunity. However, the image built by the company over time based on its financial practices largely influences investors’ judgments compared to advocated recommendations. Meanwhile, Cao et al. [13] investigated the social factor in terms of herding behavior. Herding is a situation in which all individuals behave similarly to one another, even if their private information would suggest otherwise, or they are likely to replicate rational or irrational past behavior [77]. Investors who rely on inaccurate information tend to imitate others’ ideas and decisions. Herding usually affects individual investors, especially those who are incapable of assessing the market due to literacy issues [13] and private information [17].

Religious beliefs were strong predictors, especially those related to Shariah-compliant investments, such as in Shariah equity mutual funds [21] and Sukuk [27,29,30]. Several other studies have also examined the moderating role of religion. Khan et al. [30] revealed that religion strengthened the relationship between compatibility (suitability with individuals’ actions, lifestyle, and mode of thinking), internal factors (family members, peers, friends, and relatives), external factors (social media), and intrinsic motivation (individuals’ inner satisfaction) toward Sukuk investment intention. The authors also added that Muslims who believe in a system of reward and punishment on Judgment Day are more inclined to invest in Islamic financial instruments or products.

3.3.3. Market Information

Investor behavior is influenced by market variables such as price movements, news from politics and society, forecasts for future trends, information from others, and the importance of stocks [78]. Market information is also associated with risk aversion. News of an impending economic recession influences risk-averse investors, who lose confidence in selling their stocks. Meanwhile, high-risk investors with extra cash will seize the opportunity to buy stocks at a low price [79]. Hence, market information is a positive predictor of investment intention in the stock market in Vietnam [13] and Saudi [14], unit trust in Malaysia [23], and Sukuk in the UAE [29]. Cao [13] indicated that market-based factors such as price fluctuations, market information, past trends of a stock, fundamentals of underlying stocks, customer choice, and reactions to price changes were identified as positive influences on investors’ behavior. Therefore, it implied that the market feature was highly valued in investment decisions in Vietnam. On the other hand, Khawaja and Alharbi [14], who investigated investors’ behavior in the Saudi stock market, found that it was influenced by neutral information, including internet information, information about government holders, stock market volatility, recent price swings, and press coverage. The Saudi stock market also considered all accounting information related to the firm, such as a business stock worthiness, financial status, predicted corporate gains, expected dividends, past performance, and the dividend paid.

The decision to invest among investors is influenced by their capacity to collect financial data to analyze and comprehend certain instruments and markets [23,29]. The extensive availability of information is the most significant benefit to investors, as it provides them with an advantage over other investors who may lack the necessary information to make a comprehensive decision through market analysis [23]. However, Duqi and al-Tamimi [29] found a positive coefficient for information availability and investment in Sukuk, but it was statistically insignificant. The findings show that the availability of information is insufficient from the perspective of investors, implying that UAE investors are aware of the importance of information availability in making investment decisions.

3.3.4. Firm-Specific Factors

Firm-specific factors refer to a firm’s image and reputation or an organization’s reliability, credibility, and social responsibility. Reputation is perceived as the most significant element influencing students’ attitudes towards Sukuk investments in Indonesia [27]. Since sovereign Sukuk is the most widely offered Sukuk (in terms of volume and nominal value) in the Indonesian capital market, students refer to Sukuk investment as sovereign Sukuk. Moreover, several studies [14,29] discovered a negative reputation–investment relationship between Islamic Sukuk (both sovereign and corporate) in the UAE and the stock market in Saudi Arabia. Investors with lower amounts of investment are influenced by a firm’s reputation, whereas profit takes precedence over all other considerations among investors with larger amounts of investment [14].

3.3.5. Product-Related Factors

Product-related factors can be grouped into three sub-themes, namely risk and return, brand equity, and product features. The term “return” refers to the benefit/reward that investors receive in the future from their investment. Meanwhile, “risk” refers to the uncertainty surrounding the benefits. Hence, risk and return can be considered as the investment purpose influencing investment intention. Risk and return are positively correlated with Sukuk investments in Indonesia [27] and the UAE [29]. The financial performance, which can be measured based on risk and return, was identified to have the greatest impact, followed by subjective norms and attitudes towards SRI intention in the Indian stock market [6]. Furthermore, investment in environmentally friendly companies is not only influenced by subjective norms and attitudes but is most importantly influenced by the potential future benefits based on their prior financial performance [6]. However, Annamalah et al. [23] claimed that mutual fund investment return does not have a significant impact on the investment behavior of Malaysian investors because past returns may not guarantee the current expected return.

Brand equity is embodied through variables such as brand awareness, brand quality, and brand loyalty [10]. A cross-country study performed in Turkey and Ireland [10] indicated that brand equity manifests itself through brand awareness, brand quality, and brand loyalty variables. These variables significantly impact investors’ intention to invest. In other words, changes in brand loyalty can impact the stock market investment intention. The findings also revealed a connection between brand equity perceptions and intention to invest, mediated by perceived risk, with a stronger effect in the Turkish and a weaker effect in the Irish stock market. Investors in developing markets were more risk-averse compared to those from developed markets when making investment decisions.

The third sub-theme focused on product features, such as attractiveness, accessibility, liquidity, affordability, and low riskiness [28,29]. UAE investors prefer to invest in Islamic Sukuk due to the Sukuk’s features [29]. Meanwhile, specific product features of mutual funds, including professional management, fractional purchases, lower brokerage, less volatility, diversification, regular income benefits with skilled knowledge, and limited liability with a trustworthy regulatory body, have all influenced investors’ decisions to adopt mutual funds in North India [24]. Contrarily, product features were not significant in influencing employees’ intentions to invest in retail bonds in Indonesia [28].

3.3.6. Other Factors

Other factors that influenced investment intention, according to the analysis, were demographics. There are several factors to consider under demographics, including financial or income status, marital status, occupation, level of education, age, and gender. For instance, Malaysian investors with a low financial status often take on little risk; thus, they favor the unit trust investment option [23]. Stock investors in China consider age, gender, marital status, education level, and investment experience as significant determinants, besides income status [20].

Lai [9] examined the moderating roles of gender, age, and experience using PLS multi-group analysis to determine the big five personality traits in the Taiwanese stock market. The study revealed that gender has a moderating influence on the association between subjective norms and attitude, whereas age played a moderating role in the relationship between extroversion and PBC. Moreover, stock trading experiences can significantly affect the relationship between attitude and behavior, besides the relationship between experience, subjective norms, and attitude, together with the relationship between experience and PBC. Similarly, Kaur and Kaushik [26] also discovered that demographic and socioeconomic characteristics (investment criteria and level of savings) can significantly influence the awareness of mutual funds in India. They indicated that the older and female groups negatively affected the mutual fund investing decisions.

4. Recommendations and Future Research Agenda

A variety of theories, theoretical models, and constructs were evaluated in the 28 articles, comprising 153 (independent–dependent) relationships, which provided a comprehensive picture of all the variables of investment behavioral intention examined over the last five years. This review is expected to guide future studies. The TCCM framework was used to make recommendations for future research based on the criteria from previous studies [80,81,82].

4.1. Theory

Based on the review, investor-focused studies engaged a range of theories to understand the individual intention, behavior, and decision making, namely TRA, TPB, Prospect Theory, Social Cognitive Theory, Portfolio Theory, and self-developed research models. Furthermore, the most frequently explored constructs in the studies were also derived from TRA and TPB. Although all dimensions of these well-known theories were not always significant, they were potent predictors in some circumstances.

On the other hand, attitude, subjective norms, personality traits, and risk and return are key determinants of an individual’s behavior from previous intention, adoption, and decision making studies, conjecturing the relevance of TPB as the dominant theory. The original theoretical TPB models were also usually extended with several variables, such as financial literacy, personality traits, and reputation. Moral norms, religiosity, herding behavior, social interaction, and brand equity, which were recommended as promising variables based on the weight analysis, were also recommended to be integrated into modified TPB future models. Future studies could also test the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) or any other theories related to behavioral intention. With the current emergence of fintech, many theories may be utilized to gain a better understanding of the investors’ behavioral intentions regarding digital applications. More investigations should be conducted to assess the impacts of innovative touchpoints [83] on customer behaviors. For instance, the direct or indirect relationship of fintech self-efficacy could change the structure of investing behavior.

The term “attitude” refers to a person’s overall perception of an object, which is based on their affective, cognitive, and conative responses [84]. “Affective reaction” refers to a person’s feelings and assessment of an object, person, issue, or event [85]. The feeling could be positive or negative, leading to either a favorable or unfavorable assessment of an entity, person, issue, or event [86]. Meanwhile, “cognitive reaction” relates to an individual’s knowledge, beliefs, opinions, and thoughts regarding a certain object [85]. On the other hand, “conative reaction” refers to a person’s behavioral intentions and actions toward or in the presence of a certain object [85]. Most previous studies employed cognitive [9] and affective reactions [7,11,27,28,31]. Hence, future research should identify the overall attitudes of investors instead of focusing on one or two reactions at a time. Incorporating both or all attitude components when trying to understand investors’ behavioral intentions may be more informative and provide a more comprehensive overview because attitude does not only involve cognitive appraisal, but also includes affective and behavioral/conative responses.

4.2. Context

Previous studies can be grouped into several contexts, namely dependent variables, investment scope, and countries. For the former, studies on investors’ behavior have focused on intention, actual behavior, and decision making. The majority of studies focused on intention, because intention is assumed to incorporate the motivational factors influencing a particular behavior. For a person who has complete control over his or her behavior, one could rely on behavioral intention alone to predict their behavior. Consequently, some articles used intention instead of behavior or decision making as the dependent variable.

As for the investment scope, previous studies focused on mainstream and alternative investments, such as Shariah-compliant investments and SRI. The conventional investment studies were mostly focused on the stock market, while the alternative investment studies focused on Sukuk and mutual funds. Therefore, scholars could focus on the mutual fund and bond/debt market in the future to fill the research gap. Since research on the Shariah-compliant financial products, such as Islamic mutual funds, Sukuk, or sustainable and responsible investment, is still limited, there is plenty of potential to focus on these products to contribute to the behavioral intention literature.

Additionally, our review revealed that most investor behavioral intention and decision making research was performed in individual countries, particularly in emerging countries within Asia (i.e., Malaysia, Indonesia, India, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE), with limited attention to developed markets (i.e., Italy and Ireland). Only two articles conducted comparative studies, comparing nations such as Turkey and Ireland and Mainland China and Hong Kong. Hence, more cross-country studies should be performed to provide comparative findings and theory validation (Lai, 2019).

4.3. Constructs

Our review revealed that five constructs, namely moral norms, brand equity, herding behavior, market information, and religiosity, were identified as promising predictors besides the best predictors (attitude, subjective norms, PBC, personality traits, emotion, financial literacy, and reputation) of investor intention, behavior, and decision making. However, the promising predictors need further empirical testing before they could be considered as the best predictors [62]. In the literature, brand equity is usually discussed in one of three ways, namely customer-based brand equity [87], financial brand equity [88], or a combination of the two [89]. Cal and Lambkin [10] captured customer-based brand equity (CBBE) in the Turkish and Irish stock markets. Although brand equity is widely analyzed in product and service domains, the notion has recently been extended to the financial services domain, i.e., investor-based brand equity [90]. Brand equity is regarded as a strategy for reducing perceived risk. They must be viewed as corporate brands that require marketing investment to establish brand equity and increase their reputation in order to realize their full potential. In this regard, this article draws together both marketing and finance disciplines by exchanging research approaches between the two.

Herding behavior refers to blindly following the actions of other investors. Due to a lack of certainty, investors emulate their peers or a specific group. In short, “herding” negatively impacts the individual investor’s viewpoint and decision making behaviors [16]. These investors tend to disregard their skill and understanding when making an investment decision so as to avoid being judged for making the wrong move. Herding is one of the most influential dimensions measuring social influence in India [15]. These findings also elucidated the link between investors’ decisions regarding irrational behavior and market inefficiency.

Based on our review, only four studies addressed Shariah-compliant instruments, such as Sukuk and mutual funds. All the Shariah-compliant studies examined religiosity as a unique variable, which has not been addressed in conventional studies. The impact of religion on individual behavior is referred to as religiosity. Religiosity refers to the cultural elements that make up a religion’s social structure. As such, religion can substantially impact individuals’ views, values, and behaviors [91]. The acceptance of new products [92] and purchasing behavior [93] are both influenced by religiosity. Religious views are a strong predictor of people’s investment intentions in Shariah mutual funds [21] and Sukuk [27,29,30]. Hence, religion is a positive moderator with direct effects. Both internal and external factors influencing behavioral intention are strengthened by religion. Muslims with a higher level of religiosity are obliged to invest in Islamic financial instruments or products [30], suggesting that religiosity has both direct and indirect moderating impacts. Religiosity strengthens both internal factors (family members, peers, friends, and relatives) and external factors (social media) affecting behavioral intention. Muslims who believe in a reward and punishment system on the Day of Judgment are compelled to invest in Islamic financial instruments or products, suggesting both direct and positive moderating roles of religiosity.

Paliwal et al. [25] investigated the role of demographic variables, such as gender and age, in mitigating the influence of demographic variables. Khan et al. [30] assessed the moderating effects of religious factors on the relationship between compatibility, internal influence, external influence, intrinsic motivation, and Sukuk behavioral intention in Pakistan. Akhtar and Das [8] investigated the moderating effects of financial self-efficacy on the personality traits–stock market intention relationship in India. These findings helped us in understanding users’ aspirations to channel particular strategies into a policy. Hence, it is recommended for future research to explore the moderating role of personality traits and to incorporate individual characteristics, such as gender, age, annual income, ethnicity, and education level, as potential moderating variables for stock market investment intention [4,25].

The impacts of personality traits using the big five taxonomies (agreeableness, extroversion, conscientiousness, openness to experience, and neuroticism) on the intention to invest are well documented [9,25]. Therefore, future studies could explore other dimensions of personality traits, such as risk-taking propensity and preference for innovation [8], to better predict investment intention among citizens from other countries. Future studies could also explore the possibility of measuring personality traits using a higher-order construct instead of a direct relationship between the five taxonomies and intention.

4.4. Method

All articles that were reviewed in this study used quantitative approaches to predict stock market investors’ behavioral intention and decision making. Quantitative approaches do not allow respondents to express their opinions and thoughts freely. Therefore, qualitative approaches (e.g., Delphi, focus groups, and interviews) and a broader variety of quantitative techniques (experiment and modeling techniques), which were under-represented in the reviewed studies, should be further investigated to better understand the judgments of investors. A qualitative approach is suitable for identifying constructs that are especially related to emerging issues. The content exercise produced a construct that was then finalized for a further literature review. Interviews were used as a qualitative approach in Sivaramakrishnan et al. [12]. Hence, future research could explore qualitative methods to learn more about the financial decision making of individuals. The R-squared value of less than 50% obtained via empirical results [14,23,30] indicated that other important factors are yet to be assessed. According to [94], the R² values of 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25 in many social science areas are regarded as considerable, moderate, and weak, respectively.

On the other hand, previous studies also applied cross-sectional analysis. Cross-sectional research does not consider the changes in human behavior over time [30], hence requiring subsequent analysis across time. Accordingly, a longitudinal analysis could be used to determine the effects of temporal changes on investors, which may help investigators to better understand consumers’ actual behavior in addition to their intentions [4,28,30]. We discovered that none of the reviewed articles used longitudinal analysis. Thus, future studies could employ longitudinal analysis to ascertain the effects of temporal changes on investors’ behavioral intentions.

5. Conclusions

Based on the 28 publications retrieved from the WoS and Scopus databases, we discovered that studies on investment behavioral intention–investment decision making have begun to attract academic attention. The growing interest in this research area has generated various high-impact articles documented with advanced knowledge, laying a scientific foundation for future research. The evidence from the 28 studies on investment intention, behavior, and investment decision making published between 2016 and May 2021 comprised a wide range of theoretical models and structures. This study also identified seven categories of themes/factors, namely, personal, social, macro-economic or financial development, microeconomic or firm-specific, product-related, socio-demographic, and information-related factors.

A total of 153 associations that were discovered elucidated a comprehensive picture of all the factors examined in the last six years of behavioral intention–decision making studies, establishing the groundwork for future studies. The best predictors include attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, personality traits, heuristic, emotion, financial literacy, a firm’s reputation, accounting disclosure, product features, and demographic factors. Meanwhile, the most promising constructs that need to be captured in future research are moral norms, religiosity, herding behavior, brand equity, and market information.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.C.H.; methodology, N.C.H.; software, N.C.H.; validation, A.A.-R., S.I.M.A. and S.N.A.H.; resources, A.A.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, N.C.H.; writing—review and editing, A.A.-R., S.I.M.A. and S.N.A.H.; project administration, A.A-R.; funding acquisition, A.A.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia (grant no. FRGS/1/2019/SS01/UKM/02/3).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lim, K.L.; Soutar, G.N.; Lee, J.A. Factors Affecting Investment Intentions: A Consumer Behaviour Perspective. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2013, 18, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishan, K.; Alfan, E. Financial Statement Literacy of Individual Investors in China. Int. J. China Stud. 2018, 9, 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Divanoğlu, S.U.; Bağci, H. Determining the Factors Affecting Individual Investors’ Behaviours. Int. J. Organ. Leadersh. 2018, 7, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Al Mamun, A.; Mohiuddin, M.; Al-Shami, S.S.A.; Zainol, N.R. Predicting Stock Market Investment Intention and Behavior among Malaysian Working Adults Using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. Mathematics 2021, 9, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, S.M.; Abdeljawad, A.M.; Mazouz, L.A.; Aldossary, L.Y.K.; Alsaeed, M.Y.; Sayed, M.N. The Moderating Role of Perceived Risks in the Relationship between Financial Knowledge and the Intention to Invest in the Saudi Arabian Stock Market. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2021, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, R.K.; Kumar, R.; Das, N. Individual Investors’ Intention towards SRI in India: An Implementation of the Theory of Reasoned Action. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, R.K. Past Behaviour, Financial Literacy and Investment Decision-Making Process of Individual Investors. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2020, 15, 1243–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, F.; Das, N. Predictors of Investment Intention in Indian Stock Markets. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-P.P. Personality Traits and Stock Investment of Individuals. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çal, B.; Lambkin, M. Stock Exchange Brands as an Influence on Investor Behavior. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2017, 35, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, R.K.; Das, N. Individual Investors’ Attitude towards Online Stock Trading: Some Evidence from a Developing Country. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Res. 2017, 14, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaramakrishnan, S.; Srivastava, M.; Rastogi, A. Attitudinal Factors, Financial Literacy, and Stock Market Participation. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2017, 35, 818–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.M.; Nguyen, N.T.; Tran, T.T. Behavioral Factors on Individual Investors’ Decision Making and Investment Performance: A Survey from the Vietnam Stock Market. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, M.J.; Alharbi, Z.N. Factors Influencing Investor Behavior: An Empirical Study of Saudi Stock Market. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2021, 48, 587–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, R.K.; Das, N.; Mishra, R. Behaviour of Individual Investors in Stock Market Trading: Evidence from India. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 21, 818–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moueed, A.; Hunjra, A.I. Use Anger to Guide Your Stock Market Decision-Making: Results from Pakistan. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2020, 8, 1733279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.; Hussain, R.Y.; Mehboob, I.; Arshad, M. Impact of Herding Behavior and Overconfidence Bias on Investors’ Decision-Making in Pakistan. Accounting 2019, 5, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, M.H.; Rafique, A.; Zahid, T.; Akhtar, M.W. Factors Influencing Investor’s Decision Making in Pakistan: Moderating the Role of Locus of Control. Rev. Behav. Financ. 2018, 10, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.Z.A.; Ahmad, M.; Mahmood, F. Heuristic Biases in Investment Decision-Making and Perceived Market Efficiency: A Survey at the Pakistan Stock Exchange. Qual. Res. Financ. Mark. 2018, 10, 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, M.K.Y.; Ip, W. An Exploratory Study of Investment Behaviour of Investors. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2017, 9, 184797901771152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumiati, A.; Widyastuti, U.; Takidah, E. Suherman The Millennials Generation’s Intention to Invest: A Modified Model of the Theory of Reasoned Action. Int. J. Entrep. 2021, 25, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdzan, N.S.; Zainudin, R.; Yoong, S.C. Investment Literacy, Risk Tolerance and Mutual Fund Investments: An Exploratory Study of Working Adults in Kuala Lumpur. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2020, 21, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamalah, S.; Raman, M.; Marthandan, G.; Logeswaran, A.K. An Empirical Study on the Determinants of an Investor’s Decision in Unit Trust Investment. Economies 2019, 7, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhorani, A. Factors Affecting the Financial Investors’ Decision in the Adoption of Mutual Funds. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 9, 2269–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, S.; Bhadauria, S.; Singh, S.P. Determinants of Mutual Funds Investment Intentions: Big Five Personality Dimension. Purushartha - A J. Manag. Ethics Spiritual. 2018, 11, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, I.; Kaushik, K.P.P. Determinants of Investment Behaviour of Investors towards Mutual Funds. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2016, 8, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashidiqi, C.; Arundina, T. Indonesia Students’s Intention to Invest in Sukuk: Theory of Planned Behaviour Approach. Int. J. Econ. Res. 2017, 14, 395–407. [Google Scholar]

- Dewi, M.K.; Tamara, D. The Intention to Invest in Retail Bonds in Indonesia. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2020, 9, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duqi, A.; Al-Tamimi, H. Factors Affecting Investors’ Decision Regarding Investment in Islamic Sukuk. Qual. Res. Financ. Mark. 2019, 11, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.; Khan, I.I.U.; Khan, I.I.U.; Din, S.U.; Khan, A.U. Evaluating ṣukūk Investment Intentions in Pakistan from a Social Cognitive Perspective. ISRA Int. J. Islam. Financ. 2020, 12, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongini, P.; Cucinelli, D. University Students and Retirement Planning: Never Too Early. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 775–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Shaffril, H.A.; Ahmad, N.; Samsuddin, S.F.; Samah, A.A.; Hamdan, M.E. Systematic Literature Review on Adaptation towards Climate Change Impacts among Indigenous People in the Asia Pacific Regions. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Goyal, N. Behavioural Biases in Investment Decision Making – a Systematic Literature Review. Qual. Res. Financ. Mark. 2015, 7, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, J.S.S.; Araújo, E.A. Socially Responsible Investments (SRIs) – Mapping the Research Field. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 17, 508–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescul, D.; Radu, L.D.; Păvăloaia, V.D.; Georgescu, M.R. Psychological Determinants of Investor Motivation in Social Media-Based Crowdfunding Projects: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballis, A.; Verousis, T. Behavioural Finance and Cryptocurrencies. Rev. Behav. Financ. 2022, 14, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahera, S.A.; Bansal, R. Do Investors Exhibit Behavioral Biases in Investment Decision Making? A Systematic Review. Qual. Res. Financ. Mark. 2018, 10, 210–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrati, F.; Muffatto, M. Reviewing Equity Investors’ Funding Criteria: A Comprehensive Classification and Research Agenda. Ventur. Cap. 2021, 23, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.K.; Aliyu, S.; Paltrinieri, A.; Khan, A. A Review of Islamic Investment Literature. Econ. Pap. A J. Appl. Econ. policy 2019, 38, 345–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Altman, D.; Antes, G.; Atkins, D.; Barbour, V.; Barrowman, N.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Correa, P.C.; Cantera Kintz, J.R. Ecosystem-Based Adaptation for Improving Coastal Planning for Sea-Level Rise: A Systematic Review for Mangrove Coasts. Mar. Policy 2015, 51, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, G.V. Primary, Secondary, and Meta-Analysis of Research. Educ. Res. 1976, 5, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zamore, S.; Ohene Djan, K.; Alon, I.; Hobdari, B. Credit Risk Research: Review and Agenda. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2018, 54, 811–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, W.M.H.W.; Aziz, N.A. Mobile Marketing in Business Sustainability: A Bibliometric Analysis. TEM J. 2022, 11, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.D.; Ali, M.H.; Tsai, F.M.; Iranmanesh, M.; Tseng, M.-L.; Lim, M.K. Challenges and Trends in Sustainable Corporate Finance: A Bibliometric Systematic Review. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddin, S.N.; Ismail, N.; Roslan, N.F. What We Know about Research on Life Insurance Lapse: A Bibliometric Analysis. Risks 2022, 10, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, F.M.; Bui, T.D.; Tseng, M.L.; Lim, M.K.; Hu, J. Municipal Solid Waste Management in a Circular Economy: A Data-Driven Bibliometric Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 124132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, N.; Mustaffa, Z.S.; Ahmad, N.D. Portfolio Management: A Bibliometric Review of 20 Years Publication. 2021 Int. Conf. Data Anal. Bus. Ind. ICDABI 2021 2021, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (Wos) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, A.; Bugheanu, A.M.; Boghian, R.; Madsen, D.Ø. Mapping Knowledge Area Analysis in E-Learning Systems Based on Cloud Computing. Electronics 2023, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, A.; Bugheanu, A.M.; Dinulescu, R.; Potcovaru, A.M.; Stefanescu, C.A.; Marin, I. Exploring the Research Regarding Frugal Innovation and Business Sustainability through Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkle, C.; Pendlebury, D.A.; Schnell, J.; Adams, J. Web of Science as a Data Source for Research on Scientific and Scholarly Activity. Quant. Sci. Stud. 2020, 1, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. A Tale of Two Databases: The Use of Web of Science and Scopus in Academic Papers Forthcoming in Scientometrics. arXiv 2020, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Harzing, A.W.; Alakangas, S. Google Scholar, Scopus and the Web of Science: A Longitudinal and Cross-Disciplinary Comparison. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 787–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative Research Synthesis. Int. J. Evid. Based. Healthc. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoli, C. A Guide to Conducting a Standalone Systematic Literature Review. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 37, 879–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffril, H.A.M.; Samah, A.A.; Kamarudin, S. Speaking of the Devil: A Systematic Literature Review on Community Preparedness for Earthquakes. Nat. Hazards 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaraj, A.; Rottman, J.W.; Lacity, M.C. A Review of the Predictors, Linkages, and Biases in IT Innovation Adoption Research. J. Inf. Technol. 2006, 21, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhowaiter, W.A. Digital Payment and Banking Adoption Research in Gulf Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo Zolotov, M.; Oliveira, T.; Casteleyn, S. E-Participation Adoption Models Research in the Last 17 Years: A Weight and Meta-Analytical Review. Comput. Human Behav. 2018, 81, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhajjar, S.; Ouaida, F. An Analysis of Factors Affecting Mobile Banking Adoption. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 38, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreejesh, S.; Anusree, M.R.; Mitra, A. Effect of Information Content and Form on Customers’ Attitude and Transaction Intention in Mobile Banking. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2016, 34, 1092–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, F.J.; Chamorro-Mera, A.; Rubio, S. Academic Entrepreneurship in Spanish Universities: An Analysis of the Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intention. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2017, 23, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.; Soomro, B.A. Investigating Entrepreneurial Intention among Public Sector University Students of Pakistan. Educ. Train. 2017, 59, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imani, B.; Allahyari, M.S.; Bondori, A.; Surujlal, J.; Sawicka, B. Determinants of Organic Food Purchases Intention: The Application of an Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour. Futur. Food J. Food, Agric. Soc. 2021, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.J.; Forster, M.; Bahr, K.; Benjamin, S.M. A Cross-Sectional Study Using Health Behavior Theory to Predict Rapid Compliance with Campus Emergency Notifications among College Students. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2021, 15, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissitsa, S.; Kol, O. Four Generational Cohorts and Hedonic M-Shopping: Association between Personality Traits and Purchase Intention. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 21, 545–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, M.P.H.; Fabrigar, L.R.; Fishbein, M. Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Encycl. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, A.; Afaf, G. A Comparison between Psychological and Economic Factors Affecting Individual Investor’s Decision-Making Behavior. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigerenzer, G.; Gaissmaier, W. Heuristic Decision Making. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2011, 62, 451–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.N.; Rothwell, D.W.; Cherney, K.; Sussman, T. Understanding the Financial Knowledge Gap: A New Dimension of Inequality in Later Life. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2017, 60, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.M.; Park, N.; Heo, W. Importance of Subjective Financial Knowledge and Perceived Credit Score in Payday Loan Use. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2019, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Kang, H.; Bagchi-Sen, S.; Rao, H.R. Gender Divide in the Use of Internet Applications. Int. J. E-Bus. Res. 2005, 1, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waweru, N.M.; Munyoki, E.; Uliana, E. The Effects of Behavioural Factors in Investment Decision-Making: A Survey of Institutional Investors Operating at the Nairobi Stock Exchange. Int. J. Bus. Emerg. Mark. 2008, 1, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savor, P.; Wilson, M. How Much Do Investors Care about Macroeconomic Risk? Evidence from Scheduled Economic Announcements. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2013, 48, 343–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mandler, T.; Meyer-Waarden, L. Three Decades of Research on Loyalty Programs: A Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddoud, M.Y.; Onjewu, A.K.E.; Nowiński, W.; Jones, P. The Determinants of SMEs’ Export Entry: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Rosado-Serrano, A. Gradual Internationalization vs Born-Global/International New Venture Models: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. Mark. Rev. 2019, 36, 830–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Sui, J.; Zhang, H. Switchable Ultra-Broadband Absorption and Polarization Conversion Metastructure Controlled by Light. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 34172–34187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.M.; Lou, S.J.; Huang, T.C.; Jeng, Y.L. Middle-Aged Adults’ Attitudes toward Health App Usage: A Comparison with the Cognitive-Affective-Conative Model. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2019, 18, 927–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Azjen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, D.J.; Wachter, K. A Study of Mobile User Engagement (MoEN): Engagement Motivations, Perceived Value, Satisfaction, and Continued Engagement Intention. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 56, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L. Cultivating Service Brand Equity. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davcik, N.S.; Sharma, P. Impact of Product Differentiation, Marketing Investments and Brand Equity on Pricing Strategies: A Brand Level Investigation. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 760–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.B.; Kim, W.G.; An, J.A. The Effect of Consumer-Based Brand Equity on Firms’ Financial Performance. J. Consum. Mark. 2003, 20, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalandides, A.; Jacobsen, B.P. Investor/based Place Brand Equity: A Theoretical Framework. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2009, 2, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, R. Integrating Muslim Customer Perceived Value, Satisfaction, Loyalty and Retention in the Tourism Industry: An Empirical Study. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansori, S.; Sambasivan, M.; Md-Sidin, S. Acceptance of Novel Products: The Role of Religiosity, Ethnicity and Values. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elseidi, R.I. Determinants of Halal Purchasing Intentions: Evidences from UK. J. Islam. Mark. 2018, 9, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling with R; 2017; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; Volume 21, ISSN 9783319055428. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).