Abstract

In the context of China’s three-child policy, more and more families have been changing from a one-child family to a two-child or three-child family. Both changes of family structure and the increase in child number may bring new challenges to children’s social development, emotion regulation, and parent–child relationship. This study aims to deal with the comparison of children’s emotion regulation for families with different child numbers and its relationship with parental emotion regulation and parental reactions to children’s negative emotions. We examined children’s emotion regulation, parental emotion regulation, and parental reactions to children’s negative emotions through a questionnaire survey. A total of 7807 parents from Guangdong Province in China participated in this study. The results show that: (1) A significant difference exists in children’s emotion regulation for families with different child numbers. Both one-child and two-child families present significantly higher children’s emotion regulation than three-child families; (2) There is a significant difference in parental emotion regulation, and supportive and non-supportive reactions in these families. The more children in each family, the worse the parental emotion regulation, the less supportive the reaction, and the more non-supportive the reaction; (3) Parental emotion regulation exerts a significant positive impact on children’s emotion regulation, and both supportive and non-supportive reactions play the partial mediating role. The findings emphasize more potential risks for children’s emotion regulation with the increase in family’s child number and suggest that special attention should be paid to children’s and parental emotion regulation in three-child families.

1. Introduction

With China’s three-child policy and its supporting measures implemented, good birth conditions are provided for families of childbearing age. According to the seventh national population census, more than half of Chinese families are households with two or more generations [1]; a large number of families have been changing from one-child to two- or three-child families, and they are facing the education problem of multiple children. The increase in the family’s child number maintains China’s advantages in human resources endowment but brings challenges to the development of children’s emotion regulation. Emotion regulation (ER), as an important representation of individual emotional system, matters to the core development process of children’s mental health [2], and the stable development of families and society. For this, attention to children’s ER can promote their healthy development, and facilitate the continuous release of China’s demographic dividend.

As an important field of children’s lives, family can exert a profound impact on the development of children’s ER, and parental ER and parental reactions to children’s negative emotions have a greater influence on children’s ER. In the context of China’s three-child policy, this study intends to discuss the comparison of children’s ER for families with different child numbers, the differences in parental ER as well as parental reactions to children’s negative emotions in family’s child number, and the relationship of the parental ER and parental reactions to children’s negative emotions with children’s ER.

1.1. Changes in China’s Fertility Policy and Family Structure

In 1978, the Chinese government formally wrote the family planning policy into the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China, and the policy explicitly stipulated that the country “advocates and promotes the family planning” [3]. In 1979, China began to implement the stricter family planning policy [3]. According to this policy, most Chinese couples could only have one child [4]. The family planning policy played a positive role in China’s population and development problems to some extent, but it also led to the aging of the population. After the policy had been implemented for more than 30 years, it was finally withdrawn from the historical stage of China. In response to the aging population, the Chinese government adopted a step-by-step strategy, and in 2013 and 2016, it successively promulgated and implemented the only two-child and universal two-child policies. In 2021, in order to further optimize the birth policy, the Chinese government made a major decision, that is, implementing the policy of one couple having three children and the corresponding supporting measures.

The structure of Chinese families was also changing gradually with China’s different birth policies repeatedly changed. The results of the seventh national population census showed that only 45.78% of the population born during 2019–2020 were the first child [1], indicating that China’s families changed gradually towards the non-only-child ones in structure. Guangdong Province, as China’s largest economy, ranked first in the number of newly born population for four consecutive years, becoming a typical representative in the implementation of the three-child policy. The three-child policy has provided a guarantee for China to optimize its population structure and maintain its advantages in human resource endowment. However, due to the increase of the family’s child number, great challenges were brought to children’s development, especially their social development and emotion regulation.

1.2. Impact of Family’s Child Number on Family Education and Child Development

In view of the challenges to children’s education by the changing family structure, some researchers turned their research perspectives to family education and children’s development in the context of different birth policies. A large number of studies have shown that there was a general, significant negative correlation between family’s child number and children’s educational attainment as well as academic achievements [5,6,7,8]. However, the influences of the family’s child number on children’s non-cognitive ability were controversial.

Some scholars believed that the increase in family’s child number was conducive to children’s social development. This was because the smaller family size led to children’s lack of close interpersonal contact with their siblings and their incomplete socializing process in family education, so that more psychological and behavioral problems occurred for them [9]. This standpoint was supported by some empirical studies. One study found that only children were more likely to stay alone; whether staying alone or rubbing elbows with others, they often had less interpersonal time and joys than the ones who had siblings [10]. In one-child families, many children became self-centered, less independent [11], poor in cooperation ability, and strong in subjectivity [12]. An empirical study also pointed out that children from smaller families had significantly lower levels of psychological adaptation, but with the increase in family’s child number, their emotional development was significantly improved [9].

However, other scholars believed that the increase in a family’s child number could bring more challenges to family relations and children’s social development. According to the Resource Dilution Theory, the increase in family’s child number inevitably led to excessive distribution and dilution of parents’ psychological resources such as attention, intervention, and counseling [13]. This possibly gave rise to poor outcomes in family relations and children’s social development. Some studies provided evidence for this viewpoint. A Chinese study showed that the children from three-child families presented a significantly low level of parent-child relationship than the ones from only-child or two-child families [14]. Other studies also demonstrated that children with more siblings in the family had worse emotional ability [15], and in the group suffering from mental illness diagnoses, the children from large families accounted for a higher proportion [16].

Thus, it can be seen that a family’s child number has necessary effects on different aspects of children’s development, and its important role has been confirmed in the development of children’s social and emotional abilities. As an important representation of the individual emotional system, ER refers to the process in which individuals manage, monitor, evaluate, and adjust the occurrence, experience, and expression of emotions [17] It is an internal dynamic structure [18]. ER plays an important role in children’s cognitive and social abilities and the other aspects of their development [19]. Research showed that positive ER was beneficial to children’s social interaction [20,21] while the ones who had difficult ER were prone to various behavioral problems, which restricted the development of their cognitive and social functions. Therefore, paying attention to children’s ER is not only a potential requirement for implementing the three-child policy, but also an educational need to promote the healthy development of children.

1.3. The Relationship of Children’s ER with Parental ER and Parental Reactions to Children’s Negative Emotions under the Three-Child Policy

In the context of the three-child policy, more and more families are turning into two-child and three-child families. However, regardless of the differences in the development of children’s ER in different families, parents are always an important factor in the family environment, and their own emotional feature and upbringing practice can exert a crucial impact on the development of children’s ER. Among the features, parental ER and parental reactions to children’s negative emotions have been proven to directly affect children’s ER. Therefore, children’s emotion in families with different child numbers may occur with parental ER and parental reactions to children’s negative emotions to children.

The Tripartite Model of Familial Influence (Morris et al.) showed that observing/modeling were important processes for children to acquire ER patterns from their parents [22]. When children faced emotional problems, they tended to imitate parental ER pattern [23], so parental ER could set an example for the development of children and strengthen their ER. Research showed that parental ER could be used to positively predict children’s. Parents with fewer ER difficulties had fewer problems in the development of children’s ER [24]. The higher the probability of parental ER difficulties, the worse children’s ER skills [25].

Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions refer to the reactions that parents have when dealing with children’s negative emotions, including supportive and non-supportive reactions. Supportive reactions include paying attention to emotions (such as comforting children), encouraging children to express their negative emotions, helping children solve problems, etc.; non-supportive reactions include punishing children, not recognizing children’s negative emotions, etc. [26]. The influencing mechanism of family environment on children’s ER put forward by Liu Hang et al. showed that family interaction behaviors such as parental reactions to children’s negative emotions played an important intermediary role between parents’ emotional features and children’s ER [27]. Therefore, parental ER might indirectly affect children’s through the mediation of supportive and non-supportive reactions. Research showed that a supportive reaction did play a mediating role between parental and children’s ER [28]. However, the role of non-supportive reactions in parental and children’s ER was still controversial. An empirical study showed that parents with poor ER tended to adopt non-supportive reactions to cope with children’s emotions [29], and the parent–child interaction under these performances was related to children’s poor emotional ability [30]. However, an empirical study found that the non-supportive reaction of parents in Chinese immigrant families did not have a negative impact on children’s emotional development [31]. Therefore, the role of parental reactions to children’s negative emotions in parental and children’s ER and transmission needs to be further checked.

1.4. The Current Study

To sum up, previous empirical studies have begun to focus on the comparison of children’s ER for families with different child numbers and its relationship with parental ER and parental reactions to children’s negative emotions. As China has made the latest adjustment to the birth policy, a large number of families will face the education problem of multiple children. The conclusions of the above issues in the context of China’s three-child policy are worth discussing. Based on this, this study mainly has the following three purposes: First, compare children’s ER for families with different child numbers; second, analyze the differences of parental ER and parental reactions to children’s negative emotions in family’s child number; third, confirm the relationship between parental ER, parental reactions to children’s negative emotions, and children’s ER.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The participants were all from Guangdong Province in China. A total of 7807 parents from different families participated in the study during December 2021 to March 2022. In this study, 3732 respondents (47.8%) were fathers, 4075 respondents (52.2%) were mothers. Of the children, 3912 (50.1%) were boys and 3895 (49.9%) were girls; 2235 (28.6%) aged 3 years, 2846 (36.5%) aged 4 years, and 2726 (34.9%) aged 5 years. Of these families, 1953 (25.0%) were one-child families, 4962 (63.6%) were two-child families, and 892 (11.4%) were three-child families; 3865 (49.5%) were from urban areas and 3942 (50.5%) were from rural areas. There was no significant difference in parental educational background and family monthly income between boys’ and girls’ families. The characteristics of families with different numbers of children can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

The characteristics of families with different number of children (N = 7807).

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Demographic Questionnaire

The demographic questionnaire comprised items pertaining to the children’s gender, children’s age, parental educational background, family monthly income, and family’s child number. Children’s gender was measured using a 2-point scale (1 = male, 2 = female). Children’s age was measured using a 3-point scale (1 = 3 years old, 2 = 4 years old, 3 = 5 years old). Parental educational background was measured using a 4-point scale (1 = senior high school or below, 2 = junior college, 3 = undergraduate, 4 = postgraduate or above). Family monthly income was measured using a 5-point scale (1 = under CNY 4000, 2 = CNY 4001–8000, 3 = CNY 8001–12,000, 4 = CNY 12,001–20,000, 5 = over CNY 20,000). Family’s child number was measured using a 3-point scale (1 = one-child, 2 = two-child, 3 = three-child). Furthermore, data on the areas (urban and rural) were recorded.

2.2.2. Parental Emotion Regulation

The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) developed by Gross and John [32] was used to measure parental ER. The ERQ consists of two dimensions: cognitive reappraisal (6 items) and expression suppression (4 items), with a total of 10 items. The 7-point scoring method was adopted (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Based on the double flipping procedure, the scale was translated into Chinese in this study. The English version of the ERQ was first translated into Chinese by a PhD candidate in education who is proficient in English, and then back-translated by another PhD candidate in education who is proficient in English. There was no substantial difference between the back-translated items and the original text. Cronbach’s α coefficients of the two dimensions in this study were 0.925 and 0.791, respectively. The two dimensions indicated a low positive correlation (r = 0.205, p < 0.001). In this study, the expression suppression dimension was scored inversely, that is, the higher the total score, the better the parental ER.

2.2.3. Parental Reactions to Children’s Negative Emotions

The Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale (CCNES) by Fabes, Eisenberg, and Bernzweig [33] was used to measure parental reactions to children’s negative emotions. The CCNES includes 12 hypothetical situations describing children’s experience of negative emotions. For each situation, parents are required to self-evaluate the possibility of adopting the following five reactions: problem-focused reaction, emotion-focused reaction, encouraging expression of emotion, punitive response, and minimizing response. The five reactions represent five dimensions, respectively. This study selected 10 hypothetical scenarios and used 7 points for scoring (1 = completely impossible, 7 = completely possible). This study also translated the CCNES and adjusted 10 hypothetical situations according to the Chinese cultural background.

In this study, the correlation between problem-focused reaction, emotion-focused reaction, encouraging expression of emotion as well as between punitive and minimizing responses ranged between 0.760 and 0.934 (p < 0.001), presenting a highly positive correlation. With reference to the findings of Swanson et al. [34], the averages of problem-focused reaction, emotion-focused reaction, and encouraging expression of emotion were integrated into supportive reactions, and the averages of punitive and minimizing responses were integrated into non-supportive reactions. Cronbach’s α coefficients of the supportive reactions and the non-supportive reactions in this study were 0.962 and 0.942, respectively.

2.2.4. Children’s Emotion Regulation

Children’s ER was measured by children’s Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC) developed by Shields and Cicchetti [35]. Children’s ER includes two dimensions: emotion regulation and lability/negativity. Among them, emotion regulation contains 9 items, which are used to assess children’s ability to regulate emotional reactions in various situations, including appropriate emotional expression, empathy, and emotional self-consciousness (such as being able to sympathize with others, being able to say when he/she feels sad, angry or extremely angry, worried, or afraid). The higher the score, the stronger the ability of emotion regulation is. Lability/negativity contains 15 items, which are used to assess children’s tendency of volatile, unstable, and abnormal negative emotions (such as great emotional disorder and being irritable). The higher the score, the more unstable the emotion is. This study referred to the practice of Hong Kong scholar Chang et al. [36] and adopted a 7-level rating (1 = never, 7 = always). The ERC was also translated and back-translated. The items after back-translation were not materially different from the original text. The Cronbach’s α coefficients of the two dimensions in this study were 0.737 and 0.833, respectively, and the two dimensions showed a low negative correlation r = −0.223, p < 0.001. In this study, the lability/negativity dimension was scored inversely, that is, the higher the total score, the better the children’s ER.

2.3. Procedures and Data Analysis

Based on the principle of stratified sampling, this study recruited parents of 3 to 6-year-old children. First, we chose Guangdong Province, which ranked first in the number of newly born population for four consecutive years in China. Second, we randomly selected four cities to represent Eastern, Western, Northern and Pearl River Delta Regions of Guangdong Province. These cities were Shanwei, Yangjiang, Shaoguan, and Shenzhen. Third, we randomly sampled 30 kindergartens from each city. With the consent and knowledge of the parents of the kindergartens by local kindergarten administrative departments, we distributed electronic questionnaires to the parents through the Chinese professional online questionnaire platform Wenjuanxing, and the parents volunteered to participate in completing them. The questionnaire contains instructions and fill out rules. A pre-study showed that it took about 10 min to complete all items. Therefore, in the formal study, the reaction time range of the electronic questionnaire was set to 8–15 min. If the time was too long or too short, the questionnaire could not be submitted. About two weeks later, we received 7926 questionnaires, 119 of which were answered by grandparents. After excluding the 119 questionnaires, 7807 valid questionnaires were obtained from parents.

After data collection, we conducted statistical analysis on the valid data. SPSS 26.0 was used for reliability analysis, ANOVA analysis, and correlation analysis, and the PROCESS macro-program of SPSS was used to verify mediation effect by the Bootstrap method (choosing model 4, setting up the basic number of samples as 5000).

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Children’s ER for Families with Different Child Numbers

ANOVA analysis was carried out with children’s ER as a dependent variable and family’s child number as a factor. The results showed that there were significant differences in children’s ER for families with different child numbers (F = 6.760, p < 0.01). The LSD test showed that children’s ER in one-child and two-child families was significantly higher than that in three-child families and there was no significant difference between one and two child families. Results can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

ANOVA analysis of children’s ER for families with different child numbers (N = 7807).

3.2. Differences of Parental ER and Parental Reactions to Children’s Negative Emotions in Family’s Child Number

ANOVA analysis was done with parental ER, supportive and non-supportive reactions as dependent variables, and the family’s child number as a factor. The results showed that in terms of family’s child numbers, there were significant differences in parental ER, and supportive and non-supportive reactions (F = 17.725, p < 0.001; F = 24.976, p < 0.001, F = 91.217, p < 0.001). The LSD test showed that parental ER and supportive reaction in one-child families were significantly higher than those in two-child families, and parental ER and supportive reaction in the one-child and the two-child families were significantly higher than those in three-child families; the non-supportive reaction of the three-child families was significantly higher than that of the one-child and the two-child families, and the non-supportive reaction of two-child families was significantly higher than that of one-child families. Results can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

ANOVA analysis of parental ER and parental reactions to children’s negative emotions for families with different child numbers (N = 7807).

3.3. Relationship of Parental ER, Parental Reactions to Children’s Negative Emotions, and Children’s ER

A correlation analysis was carried out of parental ER, supportive reaction, non-supportive reaction, and children’s ER. The results showed that there were significant correlations between parental ER, supportive reaction, non-supportive reaction, and children’s ER, and the correlation coefficient ranged between −0.298 and 0.387. Results can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

Correlation analysis of parental ER, parental reactions to children’s negative emotions, and children’s ER (N = 7807).

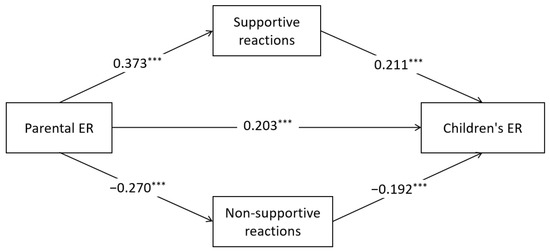

In order to further discuss the relationship between parental ER, parental reactions to children’s negative emotions, and children’s ER, a mediation effect model was constructed based on correlation analysis. A mediation model with supportive and non-supportive reactions as mediating factors was constructed by control variables of children’s gender and age, parental educational background, family monthly income, and family’s child number, and a dependent variable of children’s ER. The model can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The mediation model of parental ER and children’s ER. Note. p < 0.001 ***.

Regression analysis indicated that parental ER had a significant direct impact on children’s ER (β = 0.203, t = 17.879, p < 0.001). The results of mediation effect analysis demonstrated that the supportive reactions played a significant role in mediating parental and children’s ER (95%CI = [0.070,0.089]), while the non-supportive reactions played a significant role in mediating parental and children’s ER (95%CI = [0.045,0.059]). They accounted for 23.65% and 15.57% of the total effects, respectively. That is to say, both supportive and non-supportive reactions played a partial mediating role between parental and children’s ER. The result can be seen in Table 5.

Table 5.

ANOVA analysis of children’s ER for families with different child numbers (N = 7807).

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison of Children’s ER, Parental ER, and Parental Reactions to Children’s Negative Emotions for Families with Different Child Numbers

The results of this study show that there are significant differences in children’s ER for families with different child numbers. The one-child and two-child families have significantly higher children’s ER than three-child families. This is consistent with the findings of previous studies, that is, children’s emotional ability decreases with the increase in family’s child number [15]. This may be caused by increase home chaos and dilution of household resources. Firstly, more children mean the increase of home chaos, which leads to children’s poor ER development. Home chaos refers to the crowding degree, noise level, and organization of home environment [37]. A larger family size reported greater levels of home chaos [38]. Research showed that the higher the home chaos level, the lower the children’s ER ability [39,40]. China has a large population and tight housing conditions, and the birth of more children does not mean improvement in living places. Therefore, with general crowding degree and noise level increasing in the family environment, the development of children’s ER is affected. Secondly, the birth of multiple children leads to the dilution of educational resources. According to the Resource Dilution Theory, the increase in family’s child number leads to excessive allocation and dilution of resources at a family’s disposal [13]. On the one hand, parents’ limited time and attention are allocated to more children. The opportunities for parents and children to interact with each other are reduced, and the quality of interaction is lowered [41]. Children receive less attention and guidance from their parents. It is difficult for them to acquire positive ER strategies from their parents, which leads to their poor development in ER. On the other hand, the more children there are, the more material resources and opportunities are divided, such as toys, books, private tutoring, community activities, and so on [14]. Research showed that the birth of siblings can directly reduce the average household expenditure per capita and parental investment [42], which made children in large families gain less material resources and opportunities, and further led to the disadvantage of the development of these children’s ER.

In addition, this study also finds that there are significant differences in parental ER and parental reactions to children’s negative emotions among families with different child numbers. Specifically, the more children in the family, the worse the ER of parents, the less the supportive reaction, and the more the non-supportive reaction. This coincides with the findings of previous studies. Previous studies have shown that due to excessive stress stimulus, individuals tend to adopt an expression suppression strategy when facing negative events, and then present a bad ER pattern. In a rapidly developing Chinese society, daily expenses and education expenditures for raising children often make parents of these multi-child families face greater living economic pressure. The dual pressure sources of their work and family make the work–family conflict more pronounced [43]. After a day of emotional stress at work, parents with large families are more likely to express negative emotions when coming home from work [44]. Therefore, the more children in the family are, the worse the ER of parents is.

In addition to facing more severe life and economic pressures, parents of three-child families also bear more educational responsibilities. Their lack of parenting energy not only affects the development of children’s ER, but also makes the parents of three-child families tend to choose non-supportive reactions such as punishment, which worked well at the time when facing children’s negative emotions. In addition, the bad ER of children in three-child families mentioned above can lead to the deterioration of sibling relations [45]. According to the family system theory, each subsystem in the family is interdependent, and the emotional and behavioral dynamics of one subsystem can affect the functions of other subsystems [46]. Therefore, the interaction mode of the sibling subsystem is likely to migrate to the parent–child subsystem, presenting the characteristics that the more children in the family, the less supportive the reactions, and the more non-supportive the reactions.

4.2. Relationship between Children’s ER, Parental ER, and Parental Reactions to Children’s Negative Emotions under the Three-Child Policy

This study finds that parental ER significantly and positively affects children’s ER. This finding is consistent with previous relevant research results [27]. According to the Tripartite Model of Familial Influence, besides the influence of genetic factors, the direct influence of parental ER on children’s ER mainly comes from the observing/modeling [22]. Firstly, parental emotions can directly induce children’s corresponding emotions through emotion contagion. When parents with weak ER face the pressure of labor and livelihood in the daytime, it is difficult to change their views on negative events [47]. These accumulated negative emotional experiences are likely to be released in the interaction between parents and children. It has the potential to lead to a negative emotional atmosphere for children in three-child families, thereby affecting children’s ER. Secondly, children can acquire the relevant experience of ER directly from their parents through social referencing and modeling. Parents are the first teachers of children. The developing children can observe and imitate the ER strategies adopted by their parents when facing negative emotions and internalize the ER pattern similar to that of their parents. Hence, children whose parents have poor ER are likely to develop poor ER themselves.

Beyond that, this study also finds that both supportive and non-supportive reactions play a partial mediating role between parental and children’s ER. This verifies the view of Liu Hang et al. on the influencing mechanism of family environment on children’s ER [27]. Parents with high ER can be more aware, understand and accept emotions, and have the ability to control impulsive behaviors and engage in goal-directed behaviors when experiencing negative emotions [48]. As a result, they show more supportive reactions to children’s negative emotions. The supportive reaction of parents provides a social reference for children in ER, encourages children to have the appropriate expression of negative emotion, and provides specific suggestions and strategies for children to deal with negative emotions [22]. In this process, children can imitate and assimilate positive ER methods, thus developing better ER. Parents’ low ER is often associated with high anxiety, and the negative psychological experience under the low ER can lead to increasing non-supportive reactions such as punitive and minimizing responses. The parents’ punishment is more likely to stimulate children’s angry reaction in other social situations [49], while the minimizing response leads to children’s tendency to suppress negative emotions and may reduce children’s ability to process information about emotional events [50,51], which is not conducive to children’s ER and development. According to the findings of this study, the parents of three-child families tend to show lower levels of ER and supportive reaction and higher levels of non-supportive reaction. For this reason, we should be particularly alert to the adverse effects of parental ER and parental reactions to children’s negative emotions on children’s ER in three-child families.

5. Practice Implications and limitations

The findings of this study provide important implications for policy makers, educators, and parents. For policy makers, they should pay special attention to the emotional health of parents and children in three-child families, and provide social support for parental and children’s ER. For educators, they should publicize the importance of parental ER for children’s development, and let parents learn and understand the strategies and skills of ER through parental schools and other ways. For parents, they should be alert to the risk of parent–child emotional problems caused by the increase in family’s child number. At the same time, they ought to be aware of the important value of children’s emotions and the important role of their own emotional features in children’s ER, strengthen supportive reactions, reduce non-supportive reactions, and set a good example for children’s learning and development of ER.

However, there are some limitations for this study. Firstly, restricted by COVID-19, this study used electronic questionnaires to collect participants’ information. Although we limited the time for fill out in the electronic questionnaires, it was still difficult to verify the identity of the subjects. Future research can obtain more objective and comprehensive data through paper questionnaires, observations, and interviews. Secondly, the samples of this study are only from Guangdong Province in the east of China. Although Guangdong Province is very representative because of its high fertility rate, China has different characteristics of family emotions in different regions due to its vast territory and diverse cultures. Therefore, a wider range of samples should be considered for future research. Finally, this study has limited tests on the role of family’s child number in the influencing mechanism of children’s ER. Future research could further test the moderating effect of family’s child number in the influencing mechanism of parental ER on children’s.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, and writing—original draft preparation, M.W.; methodology, writing—review and editing, supervision, X.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62177010) and the International Joint Research Project of Faculty of Education, Beijing Normal University (Grant No. ICER202202).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Normal University (BNU202111100035 and date of approval 8 December 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because of ethical requirements.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the parents who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Office of The State Council Leading Group for the Seventh National Census. China Population Census Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Harden, B.J.; Panlilio, C.; Morrison, C.; Duncan, A.D.; Duchene, M.; Clyman, R.B. Emotion Regulation of Preschool Children in Foster Care: The Influence of Maternal Depression and Parenting. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 1124–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Wu, X.G. Fertility Decline and the Trend in Educational Gender Inequality in China. Sociol. Stud. 2011, 26, 153–177+245. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Jiang, Y.; Luo, L.; Li, P.H. The Impact of Two-Child Policy on Early Education and Development in China. Early Educ. Dev. 2022, 33, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanushek, E.A. The Trade-off between Child Quantity and Quality. J. Political Econ. 1992, 100, 84–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, S.E.; Devereux, P.J.; Salvanes, K.G. The More the Merrier? The Effect of Family Size and Birth Order on Children’s Education. Q. J. Econ. 2005, 120, 669–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åslund, O.; Grönqvist, H. Family size and child outcomes: Is there really no trade-off? Labour Econ. 2010, 17, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaabæk, E.H.; Jæger, M.M.; Molitoris, J. Family Size and Educational Attainment: Cousins, Contexts, and Compensation. Eur. J. Popul. 2020, 36, 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Hou, Y.M.; Liu, Y. An Empirical Study on the Relationship between Family Size and Child Educational Development. Educ. Res. 2014, 35, 59–69. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wikle, J.S.; Ackert, E.; Jensen, A.C. Companionship Patterns and Emotional States During Social Interactions for Adolescents with and Without Siblings. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 2190–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.R.; Wan, C.W.; Lin, G.B.; Jin, Q.C. A comparative study on Personality Quality between only-child and non-only-child primary school students in Xi‘an City. J. Psychol. Sci. 1994, 2, 70–74+127. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W. A Comparative study on the personality traits of only-child and non-only-child in high school students. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 1997, 1, 21–25. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Blake, J. Family Size and the Quality of Children. Demography 1981, 18, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Shao, Y.F.; Du, P. The Effect of Sibling Size on Parent-child Relationship. Educ. Sci. Res. 2018, 11, 68–75. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Naghavi, F.; Redzuan, M.R. Family Size and Construct of the Early Adolescent’s Emotional Intelligence. Life Sci. J. 2012, 9, 222–226. [Google Scholar]

- Kylmänen, P.; Hakko, H.; Räsänen, P.; Riala, K. Is family size related to adolescence mental hospitalization? Psychiatry Res. 2009, 177, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, L.J.; Denham, S.A.; Ganiban, J.M. Definitional Issues in Emotion Regulation Research. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, D.S.; Reidy, D.; Zeichner, A. Masculinity, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: A critical review and integrated model. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 66, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.J.; Teng, S.Y.; Li, L. The Effect of Children’s Grandparent-Grandson Attachment on Problem Behavior under the Model of Grandparents Co-parenting: The Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation. J. NENU 2021, 4, 84–91. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterpohl, N.; Wild, E. Cross-Lagged Relations Among Parenting, Children’s Emotion Regulation, and Psychosocial Adjustment in Early Adolescence. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2015, 44, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppes, G.; Suri, G.; Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation and Psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 11, 379–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.S.; Silk, J.S.; Steinberg, L.; Myers, S.S.; Robinson, L.R. The Role of the Family Context in the Development of Emotion Regulation. Soc. Dev. 2007, 16, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.A. Emotion Regulation: A Theme in Search of Definition. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 1994, 59, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Rudolph, J.; Kerin, J.; Bohadana-Brown, G. Parent emotional regulation: A meta-analytic review of its association with parenting and child adjustment. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2022, 46, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quetsch, L.B.; Wallace, N.M.; McNeil, C.B.; Gentzler, A.L. Emotion Regulation in Families of Children with Behavior Problems and Nonclinical Comparisons. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 2467–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutu, S.; Dubeau, D.; Provost, M.A.; Royer, N.; Lavigueur, S. Validation of the French-Canadian version of the CCNES (Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale). Can. J. Behav. Sci.-Rev. Can. Sci. Comport. 2002, 34, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, X.L.; Guo, Y.Y. Impact of Family Context on Children’s Emotion Regulation: Factors, Mechanism and Enlightenment. J. NENU 2019, 3, 148–155. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.R.; Qian, J.; Gao, M.; Dong, J. Emotion Socialization Mechanisms Linking Chinese Fathers’, Mothers’, and Children’s Emotion Regulation: A Moderated Mediation Model. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 3570–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deater-Deckard, K.; Wang, Z.; Chen, N.; Bell, M.A. Maternal executive function, harsh parenting, and child conduct problems. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelen, D.; Shaffer, A.; Suveg, C. Maternal Emotion Regulation: Links to emotion parenting and child emotion regulation. J. Fam. Issues 2016, 37, 1891–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Song, Q.; Doan, S.N.; Wang, Q. Maternal reactions to children’s negative emotions: Relations to children’s socio-emotional development among European American and Chinese immigrant children. Transcult. Psychiatry 2020, 57, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabes, R.A.; Eisenberg, N.; Bernzweig, J. Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale (CCNES): Description and Scoring; Arizona State University: Tempe, AZ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, J.; Valiente, C.; Lemery-Chalfant, K.; Bradley, R.H.; Eggum-Wilkens, N. Longitudinal Relations Among Parents’ Reactions to Children’s Negative Emotions, Effortful Control, and Math Achievement in Early Elementary School. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 1932–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, A.; Cicchetti, D. Emotion regulation among school-age children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale. Dev. Psychol. 1997, 33, 906–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.; Schwartz, D.; Dodge, K.A.; McBride-Chang, C. Harsh Parenting in Relation to Child Emotion Regulation and Aggression. J. Fam. Psychol. 2003, 17, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, X.P.; Li, M.-M.; Yin, D.D. Relations between Maternal Negative Emotion and Preschooler’s Externalizing Problem Behavior: The Moderating Effects of Home Chaos. J. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 41, 842–848. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Caregivers’ perceived changes in engaged time with preschool-aged children during COVID-19: Familial correlates and relations to children’s learning behavior and emotional distress. Early Child. Res. Q. 2022, 60, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.G.; Liu, W.B. Study on the Effect of Home Chaos on Emotional Regulation Strategies of Left-behind and Migrant Children Aged 4–6 Years. Stud. Early Child. Educ. 2020, 10, 30–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmama-tus-Sabah, S.; Nighat, G. Conduct problems, social skills, study skills, and home chaos in school children: A correlational study. Pak. J. Psychol. Res. 2011, 26, 201–215. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, F. Analysis on the Formation Mechanism of Psychological Problems of Elder Child in a Two-Child Family Based on Resource Dilution theory. J. Yancheng Teach. 2019, 39, 104–108. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Parental Investment After the Birth of a Sibling: The Effect of Family Size in Low-Fertility China. Demography 2020, 57, 2085–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, M. Dual Stressors and Female Pre-school Teachers’ Job Satisfaction During the COVID-19: The Mediation of Work-Family Conflict. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 691498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, Z.; Hanif, A.M.; Shenbei, Z. A Moderated Mediation Model of Emotion Regulation and Work-to-Family Interaction: Examining the Role of Emotional Labor for University Teachers in Pakistan. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221099520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Li, R.; Yang, W.; Li, R.; Tian, L.; Dou, G. Sibling Jealousy and Temperament: The Mediating Effect of Emotion Regulation in China During COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 729883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, M.J.; Paley, B. Families as Systems. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1997, 48, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, H.Y.; Gan, Y.Q.; Cui, J. Occupational stress and job burnout, job satisfaction in cinema employees: Mediating effect of emotional labor and emotion regulation. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2017, 31, 382–388. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gratz, K.L.; Weiss, N.H.; Tull, M.T. Examining emotion regulation as an outcome, mechanism, or target of psychological treatments. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 3, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calkins, S.D.; Smith, C.L.; Gill, K.L.; Johnson, M.C. Maternal Interactive Style Across Contexts: Relations to Emotional, Behavioral and Physiological Regulation During Toddlerhood. Soc. Dev. 1998, 7, 350–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Fabes, R.A.; Murphy, B.C. Parents’ Reactions to Children’s Negative Emotions: Relations to Children’s Social Competence and Comforting Behavior. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 2227–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottman, J.M.; Katz, L.F.; Hooven, C. Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: Theoretical models and preliminary data. J. Fam. Psychol. 1996, 10, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).