An Improved Corpus-Based NLP Method for Facilitating Keyword Extraction: An Example of the COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Corpus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Log-Likelihood

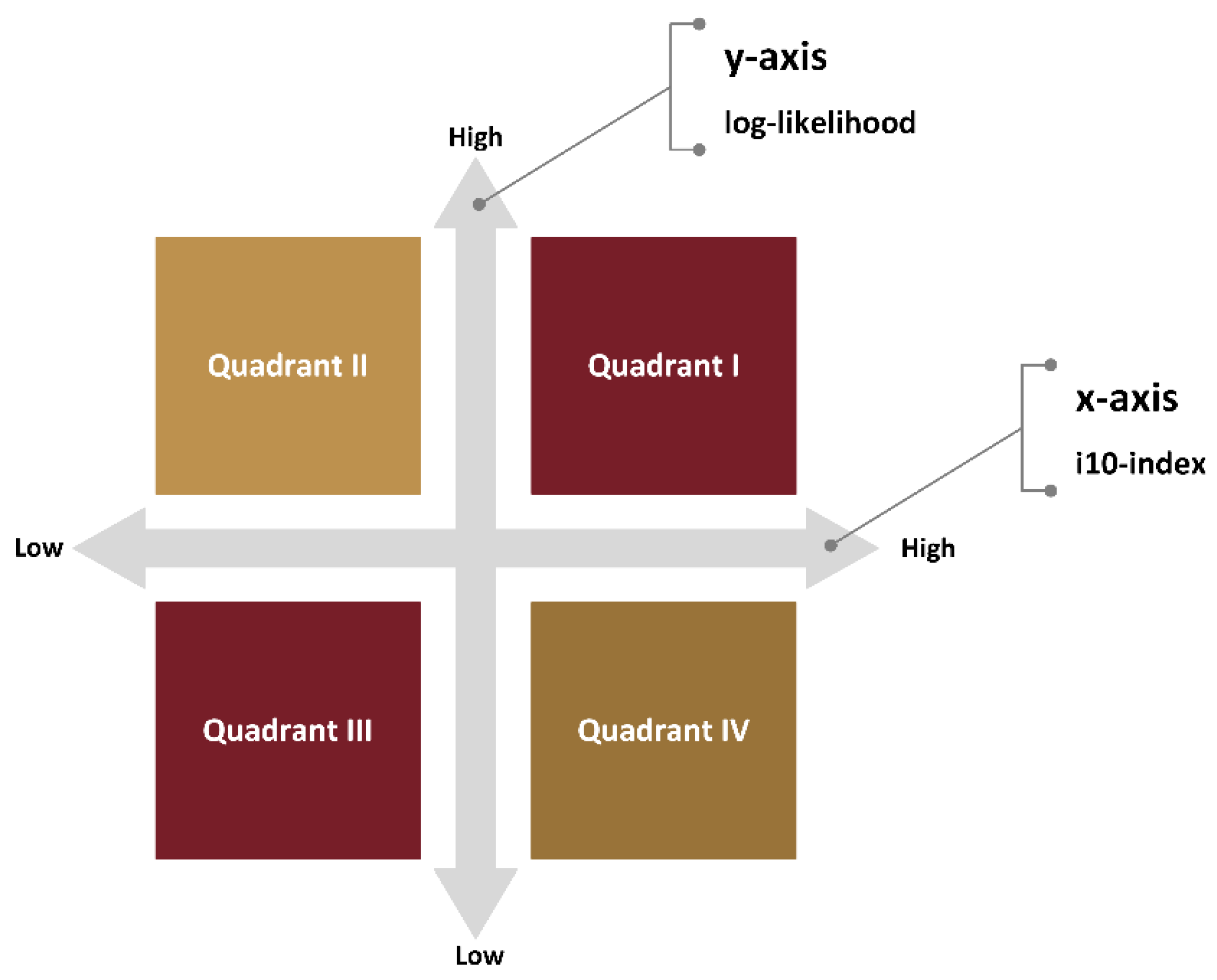

2.2. The i10-Index

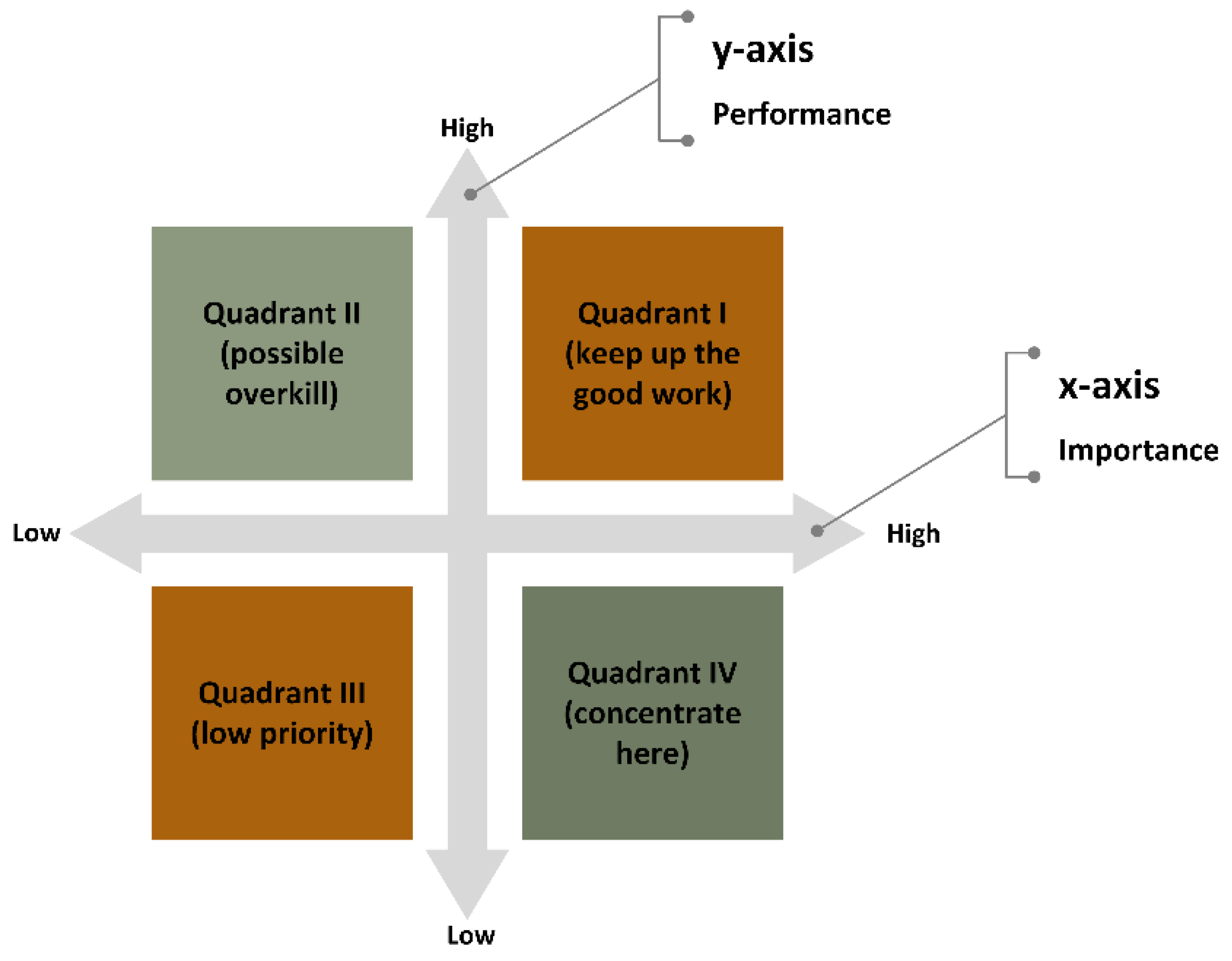

2.3. IPA Method

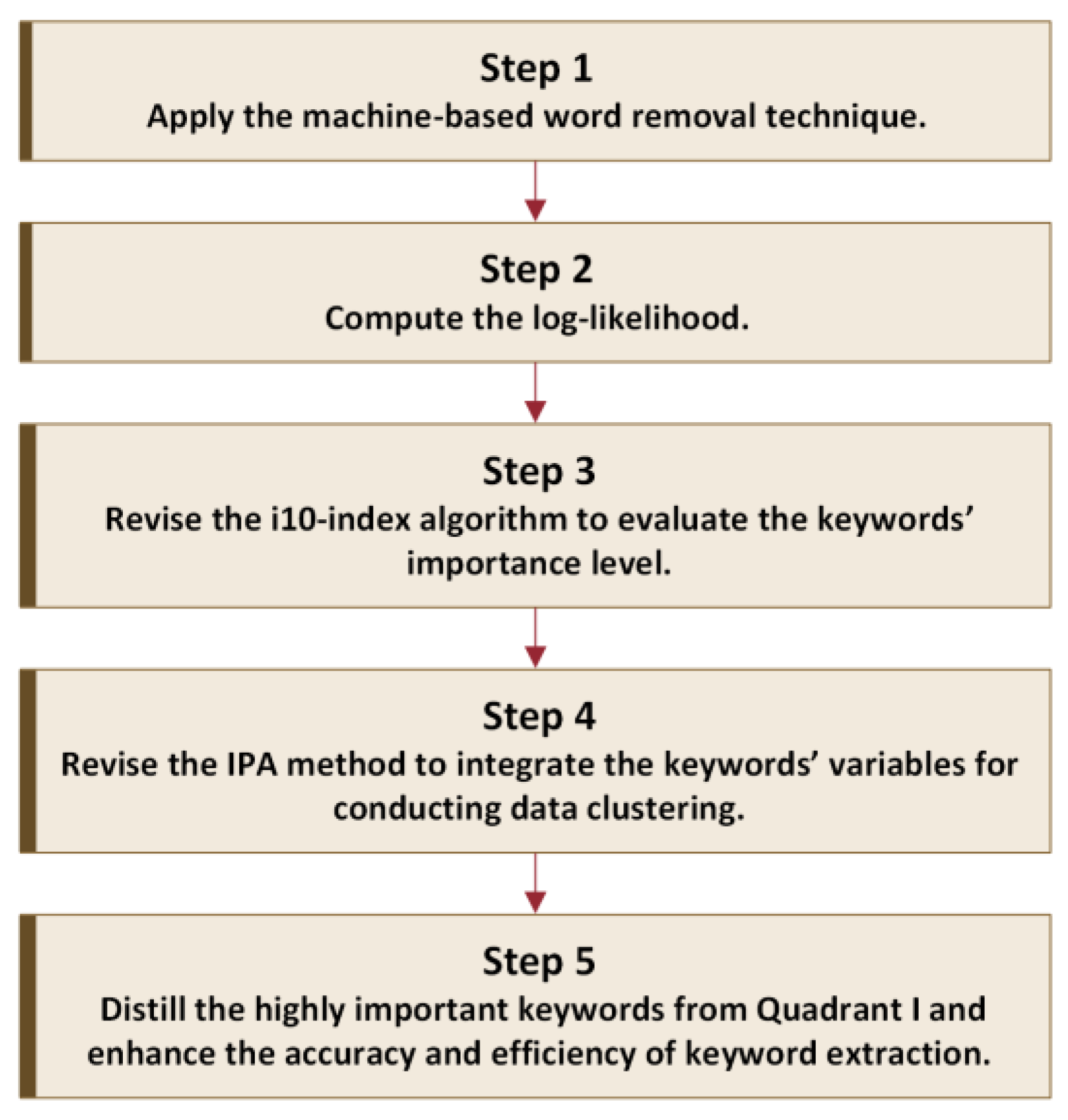

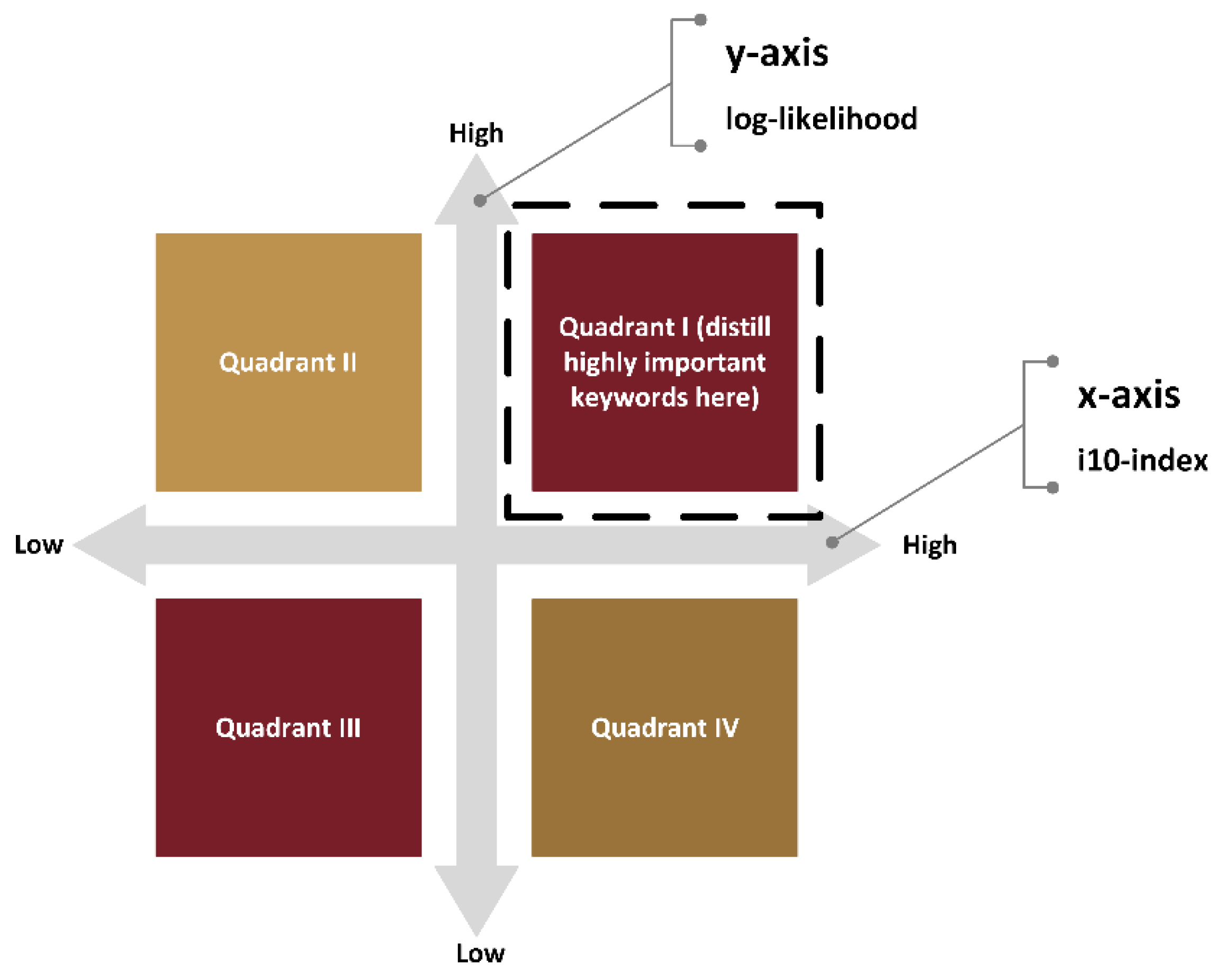

3. The Proposed Method

4. Results

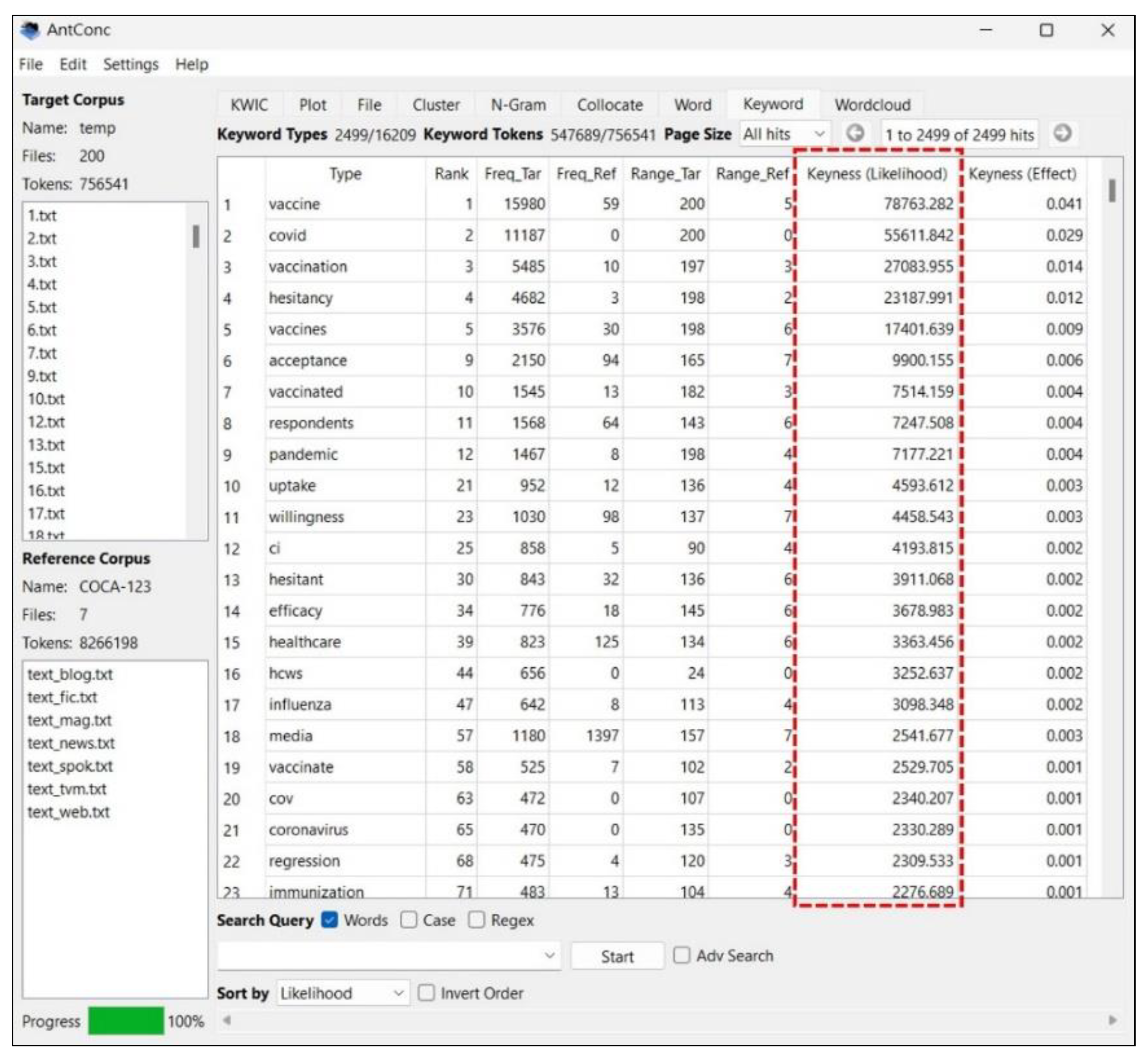

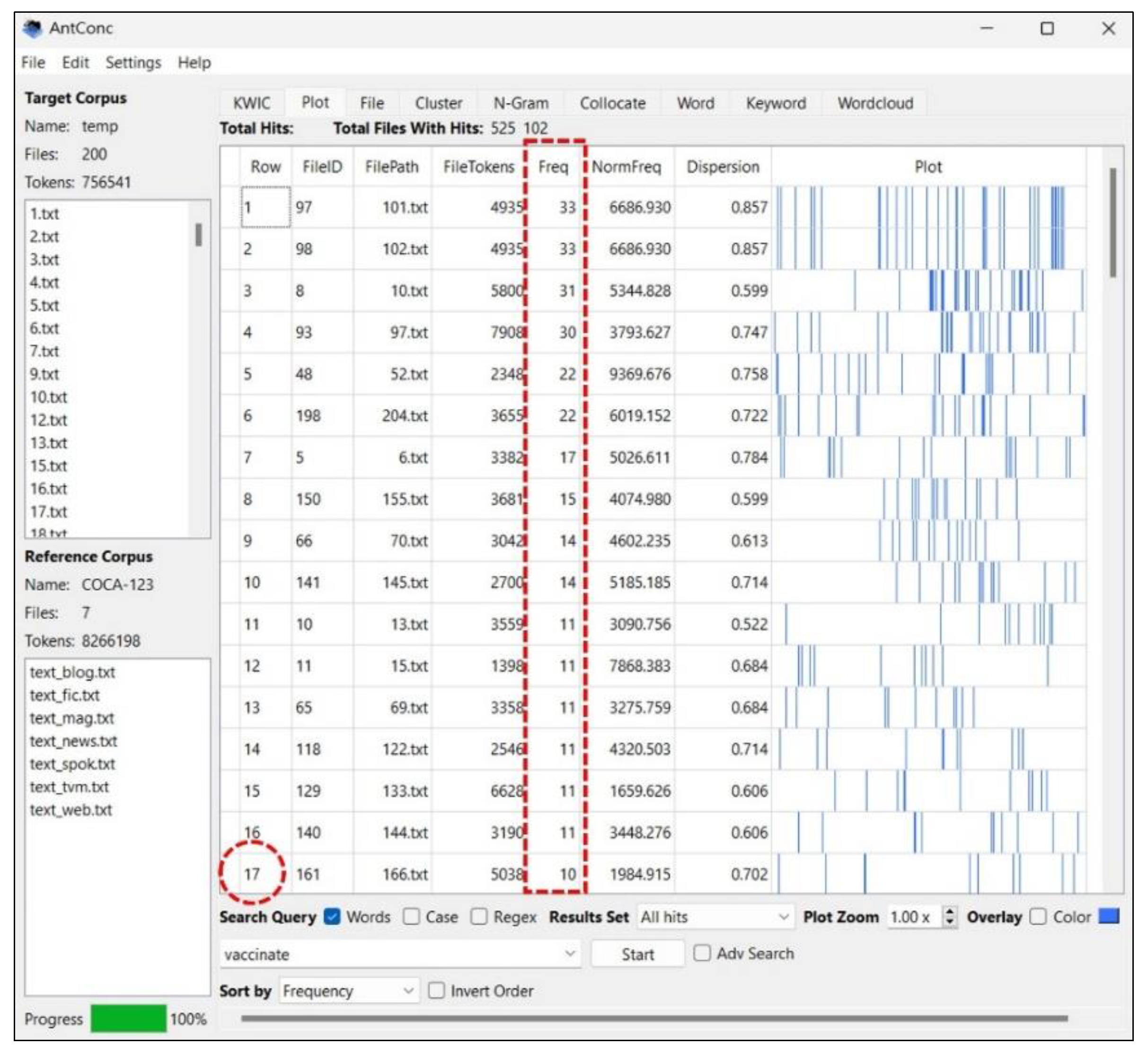

4.1. Overview of the Target Corpus

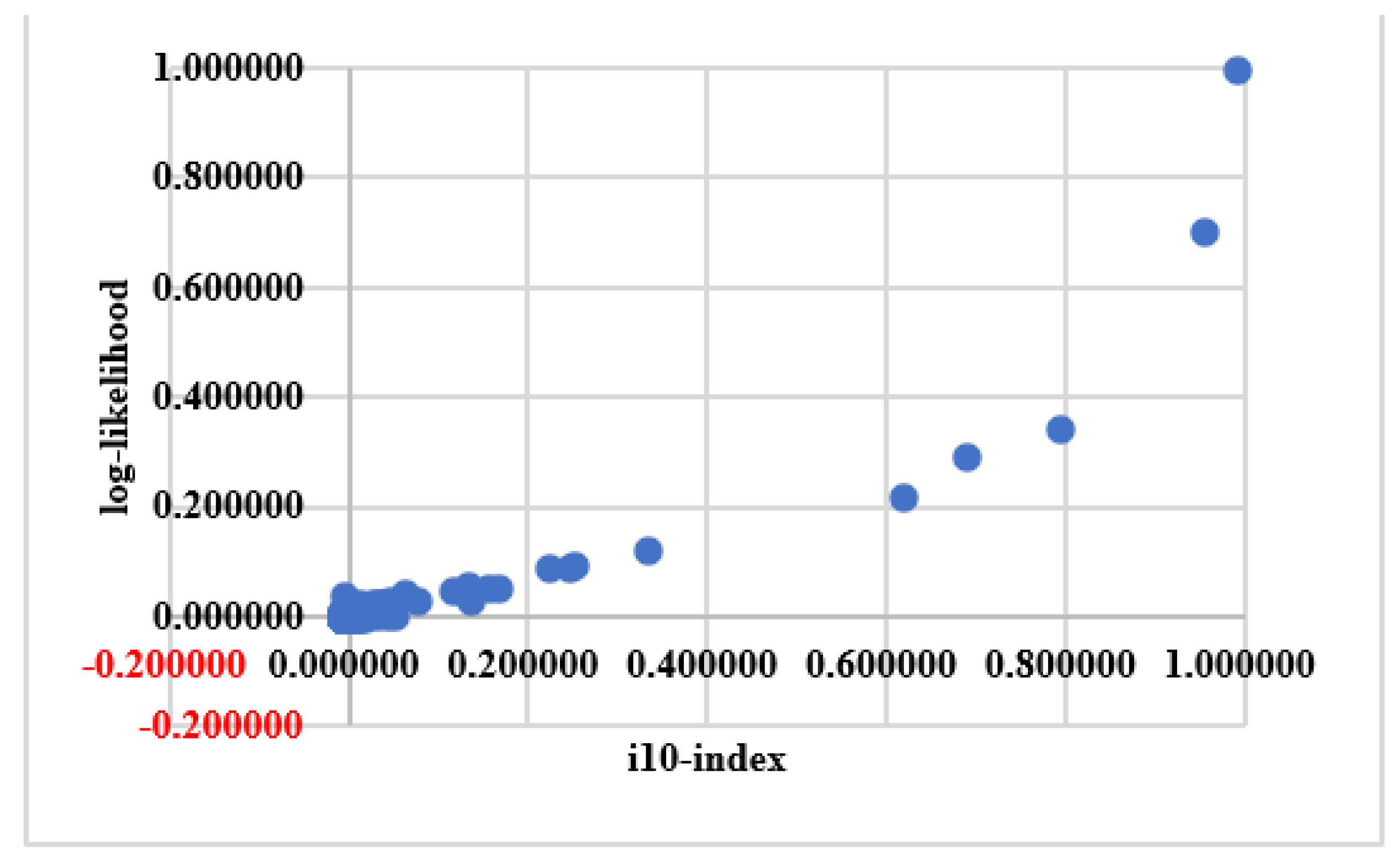

4.2. The Proposed Method

5. Discussion

5.1. Verification of the Lexical Coverage of Keywords in Different Quadrants

5.2. Comparison of the Proposed Method with the Traditional Corpus-Based NLP Methods

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meystre, S.M.; Heider, P.M.; Kim, Y.; Davis, M.; Obeid, J.; Madory, J.; Alekseyenko, A.V. Natural language processing enabling COVID-19 predictive analytics to support data-driven patient advising and pooled testing. J. Am. Med Inf. Assoc. 2021, 29, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, M. A survey on different dimensions for graphical keyword extraction techniques issues and challenges. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2021, 54, 4731–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.J.; Xu, J.Y.; Yao, X.D.; Qiu, J.F.; Chi, K.K.; Dai, G.L. A text classification model via multi-level semantic features. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trappey, A.J.C.; Liang, C.P.; Lin, H.J. Using machine learning language models to generate innovation knowledge graphs for patent mining. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, T. Accurate methods for the statistics of surprise and coincidence. Comput. Linguist. 1993, 19, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, L. AntConc; Version 4.1.3; Waseda University: Tokyo, Japan, 2022; Available online: https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Scott, M. WordSmith Tools, Version 8.0; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kithulgoda, E.; Mendis, D. From analysis to pedagogy: Developing ESP materials for the welcome address in Sri Lanka. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2020, 60, 140–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.S.; Rivers, D.J. Discursive deflection: Accusation of “fake news” and the spread of mis- and disinformation in the Tweets of President Trump. Soc. Med. Soc. 2018, 4, 2056305118776010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, R.W. An opaque engineering word list: Which words should a teacher focus on? Engl. Specif. Purp. 2017, 45, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.P.; Zhu, W.Z.; Zhou, Y.Y. CSR image construction of Chinese construction enterprises in Africa based on data mining and corpus analysis. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 7259724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.; Chang, K.H. A novel corpus-based computing method for handling critical word ranking issues: An example of COVID-19 research articles. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2021, 36, 3190–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J. How large a vocabulary do Chinese computer science undergraduates need to read English-medium specialist textbooks? Engl. Specif. Purp. 2020, 58, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, V.L. The vocabulary of agriculture semi-popularization articles in English: A corpus-based study. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2015, 39, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nation, P. Teaching and learning vocabulary. In Handbook of Research in Second Language Teaching and Learning; Hinkel, E., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hadlington, L.; Harkin, L.J.; Kuss, D.; Newman, K.; Ryding, F.C. Perceptions of fake news, misinformation, and disinformation amid the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative exploration. Psychol. Pop. Media 2022, 12, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.F.; Shen, H.Y.; Yang, S.C.; Chen, L.C. The relationships among anxiety, subjective well-being, media consumption, and safety-seeking behaviors during the COVID-19 epidemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.C.; Le Han, E.; Luli, G.K. COVID-19 vaccine-related discussion on Twitter: Topic modeling and sentiment analysis. J. Med Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otegi, A.; San Vicente, I.; Saralegi, X.; Penas, A.; Lozano, B.; Agirre, E. Information retrieval and question answering: A case study on COVID-19 scientific literature. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 240, 108072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.; Pant, A.B. Mitigating COVID-19 in the face of emerging virus variants, breakthrough infections and vaccine hesitancy. J. Autoimmun. 2022, 127, 102792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, E.; Simas, C.; Larson, H.J. An epidemic of uncertainty: Rumors, conspiracy theories and vaccine hesitancy. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfattheicher, S.; Petersen, M.B.; Bohm, R. Information about herd immunity through vaccination and empathy promote COVID-19 vaccination intentions. Health Psychol. 2022, 41, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.H. What we do know and do not yet know about COVID-19 vaccines as of the beginning of the year 2021. J. Korean Med Sci. 2021, 36, e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A.L.; Johnson, T.; Phillips, L.; Nelson, T.B. Sources of vaccine hesitancy: Pregnancy, infertility, minority concerns, and general skepticism. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofab433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khairat, S.; Zou, B.M.; Adler-Milstein, J. Factors and reasons associated with low COVID-19 vaccine uptake among highly hesitant communities in the US. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2022, 50, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, M.K.; Mehl, R.; Costantine, M.M.; Johnson, A.; Cohen, J.; Summerfield, T.L.; Landon, M.B.; Rood, K.M.; Venkatesh, K.K. Characteristics and perceptions associated with COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy among pregnant and postpartum individuals: A cross-sectional study. BJOG 2022, 129, 1342–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.Y.; Cheung, J.K.; Wu, P.; Ni, M.Y.; Cowling, B.J.; Liao, Q.Y. Temporal changes in factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and uptake among adults in Hong Kong: Serial cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Reg. Health-W. Pac. 2022, 23, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelkar, A.H.; Blake, J.A.; Cherabuddi, K.; Cornett, H.; McKee, B.L.; Cogle, C.R. Vaccine enthusiasm and hesitancy in cancer patients and the impact of a webinar. Healthcare 2021, 9, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, J.; Marani, H.; Monkman, H. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Canada: Content analysis of tweets using the theoretical domains framework. J. Med Internet Res. 2021, 23, e26874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraya, A.M.; Salami, R.M.; Alqahtani, S.S.; Madkhali, O.A.; Hijri, A.M.; Qassadi, F.A.; Albarrati, A.M. COVID-19 vaccines and restrictions: Concerns and opinions among individuals in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.F.; Chen, L.C.; Yang, S.C.; Hong, S. Knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) toward COVID-19 pandemic among the public in Taiwan: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiber, A.; Prinster, T.B.; Stecko, H.; Wang, T.N.; Scott, S.; Shah, S.H.; Wyne, K. COVID-19 vaccination rates and vaccine hesitancy among Spanish-speaking free clinic patients. J. Community Health 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Barlow, M. A corpus-based analysis of research article macrostructure patterns. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2022, 58, 101138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Tao, Y.T. Stance markers in English medical research articles and newspaper opinion columns: A comparative corpus-based study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.M.; Chalupnik, M. Sacrificing long hair and the domestic sphere: Reporting on female medical workers in Chinese online news during COVID-19. Discourse Soc. 2022, 33, 650–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.; Chang, K.H.; Chung, H.Y. A novel statistic-based corpus machine processing approach to refine a big textual data: An ESP case of COVID-19 news reports. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, C.; Culligan, B.; Phillips, J. The New General Service List. 2013. Available online: http://www.newgeneralservicelist.org (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Chopra, K.; Swanson, E.W.; Susarla, S.; Chang, S.; Stevens, W.G.; Singh, D.P. A comparison of research productivity across plastic surgery fellowship directors. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2016, 36, 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, J.A.T. The i100-index, i1000-index and i10,000-index: Expansion and fortification of the Google Scholar h-index for finer-scale citation descriptions and researcher classification. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 3667–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martilla, J.A.; James, J.C. Importance-performance analysis. J. Mark. 1977, 41, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayson, P. From key words to key semantic domains. Int. J. Corpus Linguist. 2008, 13, 519–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.E. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 16569–16572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Bornmann, L. A new family of cumulative indexes for measuring scientific performance. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi-Bazargani, H.; Bakhtiary, F.; Golestani, M.; Sadeghi-Bazargani, Y.; Jalilzadeh, N.; Saadati, M. The research performance of Iranian medical academics: A national analyses. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, J.; Kim, H.M. Approach for importance-performance analysis of product attributes from online reviews. J. Mech. Des. 2021, 143, 081705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasovska, I.; Kubickova, M.; Ryglova, K. Importance-performance analysis approach to destination management. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Shen, H.C.; Zuo, J. Risks in prefabricated buildings in China: Importance-performance analysis approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.L. A new hybrid MCDM model for esports caster selection. J. Mult.-Valued Log. Soft Comput. 2021, 37, 573–590. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, J.F.; Wang, C.P.; Chang, K.L.; Hu, Y.C. Selecting bloggers for hotels via an innovative mixed MCDM model. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.C.; Chang, K.H.; Lai, H.H.; Liu, Y.Y.; Wang, J.C. A novel rugby team player selection method integrating the TOPSIS and IPA methods. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2021, 52, 137–158. [Google Scholar]

- Otter, D.W.; Medina, J.R.; Kalita, J.K. A survey of the usages of deep learning for natural language processing. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 604–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojanapunya, P.; Todd, R.W. Log-likelihood and odds ratio: Keyness statistics for different purposes of keyword analysis. Corpus Linguist. Linguist. Theo. 2018, 14, 133–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durbahn, M.; Rodgers, M.; Peters, E. The relationship between vocabulary and viewing comprehension. System 2020, 88, 102166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, E.; Leeser, M.J. The relationship between lexical coverage and type of reading comprehension in beginning L2 Spanish learners. Mod. Lang. J. 2022, 106, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xodabande, I.; Ebrahimi, H.; Karimpour, S. How much vocabulary is needed for comprehension of video lectures in MOOCs: A corpus-based study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 992638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phadermrod, B.; Crowder, R.M.; Wills, G.B. Importance-Performance Analysis based SWOT analysis. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 2019, 44, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anakpo, G.; Mishi, S. Hesitancy of COVID-19 vaccines: Rapid systematic review of the measurement, predictors, and preventive strategies. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2074716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allington, D.; McAndrew, S.; Moxham-Hall, V.; Duffy, B. Coronavirus conspiracy suspicions, general vaccine attitudes, trust and coronavirus information source as predictors of vaccine hesitancy among UK residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2021, 53, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascherini, M.; Nivakoski, S. Social media use and vaccine hesitancy in the European Union. Vaccine 2022, 40, 2215–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, H.; Ma, X.H.; Wu, X. The prevalence and determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the age of infodemic. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2013694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierri, F.; Perry, B.L.; DeVerna, M.R.; Yang, K.C.; Flammini, A.; Menczer, F.; Bryden, J. Online misinformation is linked to early COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy and refusal. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.N.; Guo, Y.Q.; Zhou, Q.; Tan, Z.X.; Cao, J.L. The mediating roles of medical mistrust, knowledge, confidence and complacency of vaccines in the pathways from conspiracy beliefs to vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Corpus 1 (Target Corpus) | Corpus 2 (Benchmark Corpus) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of word | A | B | A + B |

| Frequency of other words | C − A | D − B | C + D − A − B |

| Total words | C | D | C + D |

| Target Corpus | Refined Target Corpus | Data Discrepancy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Word types | 16,209 | 10,922 | 5287 (−32.62%) |

| Tokens | 756,541 | 142,274 | 614,267 (−81.19%) |

| Keywords | Keywords | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine | 0.992119 | 0.995679 | CDC | 0.017245 | 0.003960 |

| COVID | 0.956943 | 0.701742 | Authorities | 0.017245 | 0.003372 |

| Vaccination | 0.796139 | 0.339544 | Behavioral | 0.017245 | 0.002172 |

| Hesitancy | 0.690611 | 0.290080 | Intent | 0.017245 | 0.000509 |

| Vaccines | 0.620260 | 0.216615 | Regression | 0.012219 | 0.025001 |

| Acceptance | 0.333827 | 0.121374 | Determinants | 0.012219 | 0.011189 |

| Vaccinated | 0.253425 | 0.091080 | Infected | 0.012219 | 0.009070 |

| Pandemic | 0.248400 | 0.086803 | Prevalence | 0.012219 | 0.008959 |

| Respondents | 0.223275 | 0.087695 | Susceptibility | 0.012219 | 0.006187 |

| Willingness | 0.167998 | 0.052285 | Ethnicity | 0.012219 | 0.005775 |

| CI | 0.157948 | 0.048924 | Pfizer | 0.012219 | 0.005480 |

| Media | 0.137848 | 0.027948 | Tweets | 0.012219 | 0.004721 |

| Uptake | 0.132822 | 0.054000 | Rollout | 0.012219 | 0.002668 |

| Healthcare | 0.132822 | 0.038382 | Pharmaceutical | 0.012219 | 0.002276 |

| Hesitant | 0.117747 | 0.045335 | Resistant | 0.012219 | 0.002186 |

| Vaccinate | 0.077546 | 0.027796 | BNT | 0.012219 | 0.001973 |

| Efficacy | 0.062471 | 0.042388 | Physicians | 0.012219 | 0.001452 |

| HCWs | 0.062471 | 0.036975 | HBM | 0.012219 | 0.001092 |

| Conspiracy | 0.052420 | 0.016141 | VHS | 0.012219 | 0.000427 |

| CoV | 0.047395 | 0.025391 | USA | 0.012219 | 0.000007 |

| Questionnaire | 0.047395 | 0.023626 | Herd | 0.007194 | 0.009008 |

| UK | 0.047395 | 0.011462 | Distrust | 0.007194 | 0.007144 |

| Misinformation | 0.042370 | 0.020678 | Distribution | 0.007194 | 0.006593 |

| Chronic | 0.042370 | 0.003145 | Literacy | 0.007194 | 0.005212 |

| China | 0.042370 | 0.002102 | Measles | 0.007194 | 0.004178 |

| Immunization | 0.037345 | 0.024584 | Subgroups | 0.007194 | 0.003849 |

| SARS | 0.037345 | 0.023872 | Dose | 0.007194 | 0.003719 |

| Immunity | 0.037345 | 0.022916 | Providers | 0.007194 | 0.002686 |

| Vaccinations | 0.037345 | 0.020081 | Canada | 0.007194 | 0.000600 |

| Fig | 0.037345 | 0.008768 | Epidemic | 0.007194 | 0.000574 |

| AOR | 0.037345 | 0.006883 | Supplementary | 0.002169 | 0.004842 |

| Effectiveness | 0.032320 | 0.021091 | Statistically | 0.002169 | 0.004548 |

| Demographic | 0.032320 | 0.020223 | Additionally | 0.002169 | 0.004364 |

| Flu | 0.032320 | 0.013837 | Preventive | 0.002169 | 0.003756 |

| Sociodemographic | 0.032320 | 0.012548 | Administered | 0.002169 | 0.003678 |

| Saudi | 0.032320 | 0.005046 | SD | 0.002169 | 0.003633 |

| Anti | 0.032320 | 0.003917 | AstraZeneca | 0.002169 | 0.003169 |

| Arabia | 0.032320 | 0.002004 | Consent | 0.002169 | 0.002728 |

| Coronavirus | 0.027295 | 0.025265 | Adherence | 0.002169 | 0.001786 |

| Predictors | 0.027295 | 0.013092 | Correlation | 0.002169 | 0.001591 |

| mRNA | 0.027295 | 0.009397 | Propensity | 0.002169 | 0.001341 |

| Severity | 0.027295 | 0.008802 | Viral | 0.002169 | 0.001207 |

| Odds | 0.027295 | 0.008023 | Unvaccinated | 0.002169 | 0.001146 |

| VH | 0.027295 | 0.005815 | Disparities | 0.002169 | 0.001092 |

| Refusal | 0.022270 | 0.015445 | WTP | 0.002169 | 0.000531 |

| Mistrust | 0.022270 | 0.014165 | Undecided | 0.002169 | 0.000525 |

| Adverse | 0.022270 | 0.010694 | Unsure | 0.002169 | 0.000382 |

| Likelihood | 0.017245 | 0.007472 | EUA | 0.002169 | 0.000353 |

| Doses | 0.017245 | 0.005757 | Contextual | 0.002169 | 0.000336 |

| Word Types | Tokens | Lexical Coverage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadrant I | 98 | 74,225 | 9.81% |

| Quadrant II | 70 | 5946 | 0.79% |

| Quadrant III | 1127 | 26,460 | 3.5% |

| Quadrant IV | 40 | 6217 | 0.82% |

| Total keywords | 1335 | 112,848 | 14.92% |

| Optimizing the Keyword List in a Machine-Based Way | Evaluating the Keywords’ Importance Level | Integrating the Variables to Conduct Data Clustering | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AntConc 4.1.3 [6] | No | No | No |

| Kithulgoda and Mendis’s corpus-based NLP method [8] | No | No | No |

| Zhong et al.’s corpus-based NLP method [11] | No | No | No |

| The proposed method | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Rank | Log-Likelihood | Keyword | Rank | Log-Likelihood | Keyword |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 78763.28 | Vaccine | 26 | 4159.43 | Associated |

| 2 | 55611.84 | Covid | 27 | 4141.98 | Public |

| 3 | 27083.96 | Vaccination | 28 | 4132.75 | Sample |

| 4 | 23187.99 | Hesitancy | 29 | 4126.79 | Studies |

| 5 | 17401.64 | Vaccines | 30 | 3911.07 | Hesitant |

| 6 | 11144.91 | Study | 31 | 3893.01 | Individuals |

| 7 | 10707.55 | Health | 32 | 3876.22 | Perceived |

| 8 | 10138.47 | Participants | 33 | 3717.94 | Table |

| 9 | 9900.16 | Acceptance | 34 | 3678.98 | Efficacy |

| 10 | 7514.16 | Vaccinated | 35 | 78763.28 | Vaccine |

| 11 | 7247.51 | Respondents | 36 | 3620.22 | Intention |

| 12 | 7177.22 | Pandemic | 37 | 3511.41 | Higher |

| 13 | 7161.98 | Et | 38 | 3453.18 | Social |

| 14 | 6754.69 | Survey | 39 | 3453.01 | Disease |

| 15 | 6284.55 | Were | 40 | 3363.46 | Healthcare |

| 16 | 6132.97 | Among | 41 | 3355.39 | Data |

| 17 | 5717.95 | Population | 42 | 3293.09 | Attitudes |

| 18 | 5664.36 | Al | 43 | 3263.40 | Information |

| 19 | 5267.72 | Of | 44 | 3256.14 | Countries |

| 20 | 4692.43 | Factors | 45 | 3252.64 | Hcws |

| 21 | 4593.61 | Uptake | 46 | 3138.45 | Confidence |

| 22 | 4489.16 | Reported | 47 | 3136.38 | Safety |

| 23 | 4458.54 | Willingness | 48 | 3098.35 | Influenza |

| 24 | 4376.07 | Risk | 49 | 2941.16 | Infection |

| 25 | 4193.82 | CI | 50 | 2927.96 | Results |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, L.-C. An Improved Corpus-Based NLP Method for Facilitating Keyword Extraction: An Example of the COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Corpus. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3402. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043402

Chen L-C. An Improved Corpus-Based NLP Method for Facilitating Keyword Extraction: An Example of the COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Corpus. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3402. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043402

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Liang-Ching. 2023. "An Improved Corpus-Based NLP Method for Facilitating Keyword Extraction: An Example of the COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Corpus" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3402. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043402

APA StyleChen, L.-C. (2023). An Improved Corpus-Based NLP Method for Facilitating Keyword Extraction: An Example of the COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Corpus. Sustainability, 15(4), 3402. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043402