The Challenges of Sustainable Tourism Development in Special Environmental Protected Areas: Local Resident Perceptions in Datça-Bozburun

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What is the process of tourism development in Datça-Bozburun SEPA?

- How are tourism’s development and current situation perceived in Datça-Bozburun SEPA?

- What are tourism perception’s economic, environmental, social, and cultural effects in Datça-Bozburun SEPA?

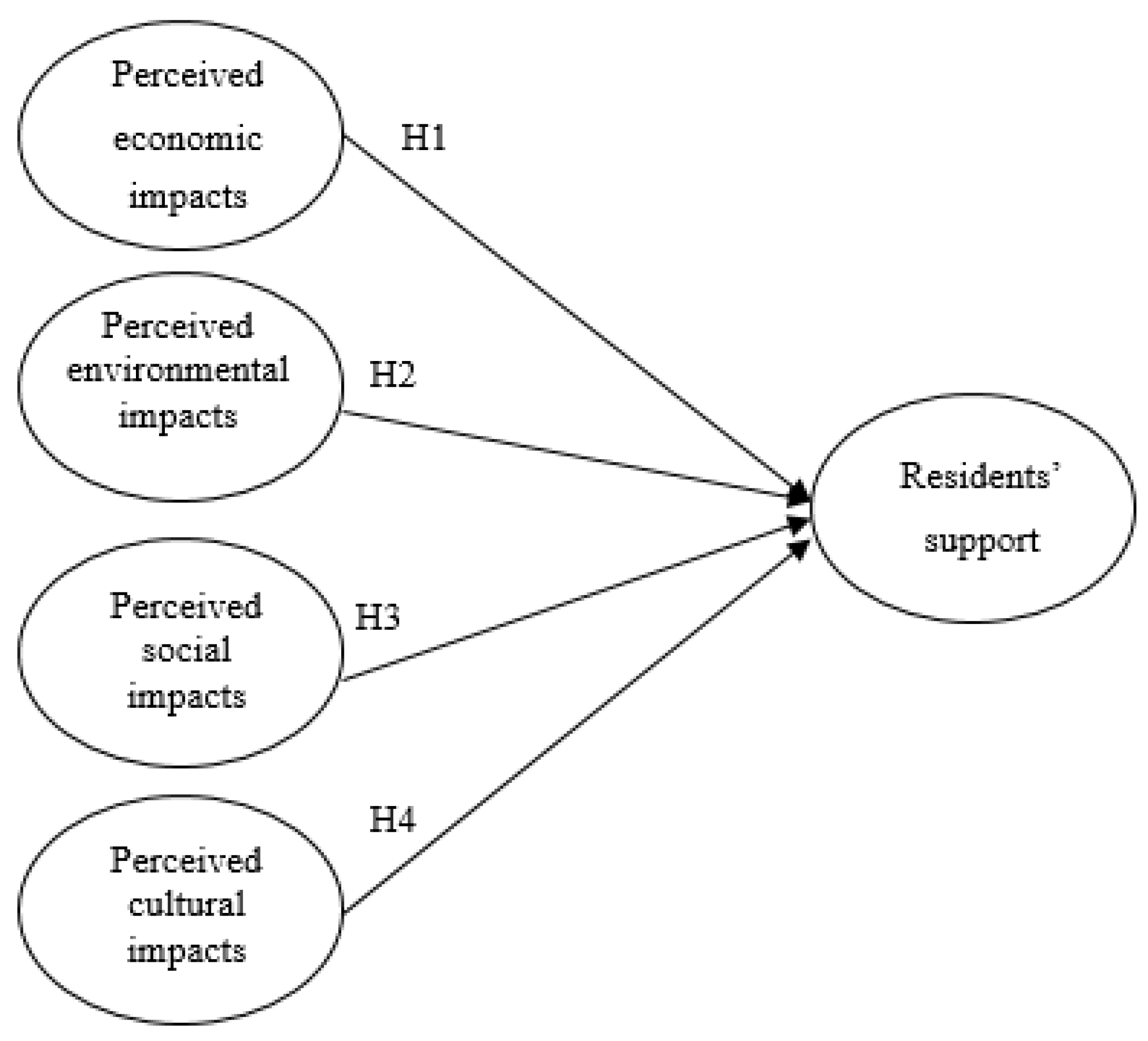

- How do economic, environmental, social, and cultural dimensions affect local people’s support for tourism?

2. Literature

2.1. The Perceived Tourism Impacts

2.2. Residents’ Support

3. Methodology

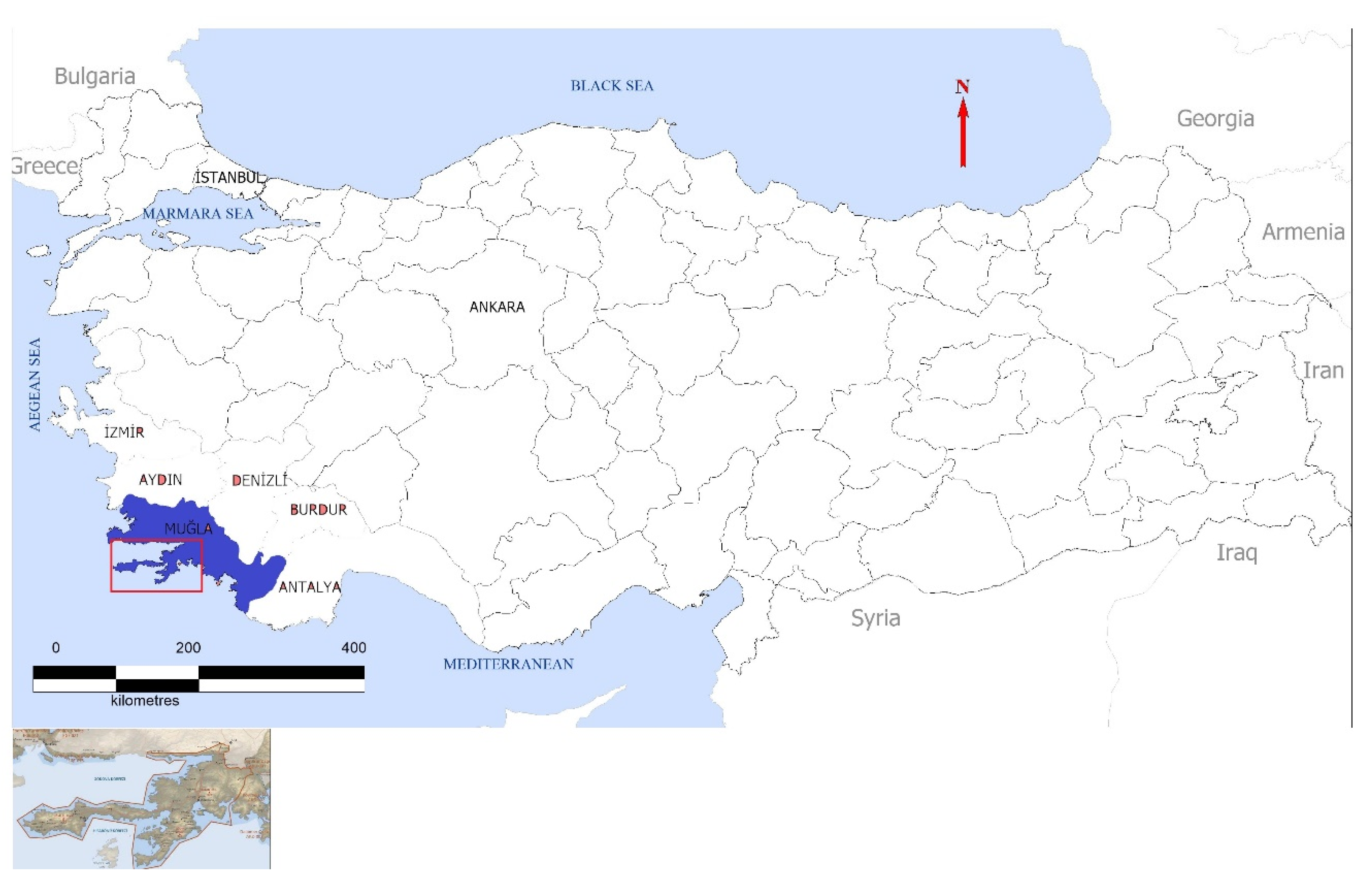

3.1. The Study Area

3.2. Research Design

3.3. Qualitative Study

3.4. Quantitative Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Qualitative Findings

4.1.1. Tourism Development

SB: Being in a special environmental protection area protects us. People inevitably own up to these regulations. They may not have been wholly accepted yet, but there is increasing awareness. This issue comes up frequently, and it relates to many areas, from construction to marine and environmental use to zoning permits. It seems like an obstacle in some places, but it is there for protection. There is something remarkable. Being a particular environmental protection area covers many issues, from endemic plant species and animals to agricultural land use, and the people are conscious of it.

MB: Planning exists, of course; it should exist. That is what we had always suggested. We suggested that beaches, bars, and restaurants could be planned in a virgin place … For example, Sığ Liman (Sığ Port) would have been quite the place. These were discussed at the meetings, but now it is impossible because too many houses have been built there, and the property owners will object to the idea. But back then, there was no one. The Sığ Liman shore was lovely. The public authorities have already tried to build a large beach there. It is possible to create a beach where 1000–1500 people can swim. However, sand reinforcement is needed; the sand there has thinned. In the past, they used that beautiful fine sand to make plaster for building houses on the peninsula. There was no road, so what should the people do?

AB: The National Geographic magazine placed the Carian Trail among one of the six best adventure routes in the world in all its editions in Europe this year. It is going to be published in Russia as well. The most significant elements are that the routes are beautiful, the region is diverse, and there is the sea. People love the sea. The Datça Peninsula has a coastline of 150 km, where you can enjoy the sea continuously, on more than 50 beaches, unlike the Lycian Trail, which has less than 50 beaches. It is, therefore, an attractive place; both Datça Peninsula and Bozburun Peninsula have great potential. From the perspective of alternative tourism, both have potential with their villages, nature, trails, and the sea. There just needs to be more local businesses and local governments that support alternative tourism. So far, it has always been about individual efforts.

ZK: Each square meter in Datça is part of a SEPA. This situation ties the hands of the landlords and the villagers. We cannot do any construction on our land. Our children cannot get married and own a house. They own every place and make the life of the villagers difficult. I want the site status of Datça to be removed.

Planning Issues and Infrastructure

MÖ: People may be pleased now, but I am not so happy. In other words, tourism’s rapid and uncontrolled development is too much for Selimiye. Selimiye is not a very big place. My biggest fear is that when tourism develops rapidly, the region also receives rapid migration, then the original structure is lost. I believe the guests want to meet with the locals and stay at their houses and hostels to eat their food.

UB: I do not need infrastructure. But there is a general situation here; everyone wants infrastructure. It is probably impossible to do it now, but the infrastructure is necessary. The water supply was terrible; they’ve just improved the water system. There were constant power cuts. It is probably a rare situation; I think they have a method of periodically reducing and increasing power. There are a lot of power cuts related to this. Naturally, this place is quiet, an area known for its quietness. Ninety-seven percent of the inhabitants do not have a generator either because if everyone runs their generators in the event of a power cut, this place will be boisterous. That’s why no one buys a generator, not to break the silence. But everything breaks down because of the frequent power cuts. One day it is the air conditioner; the other day, the refrigerator. Even if the guests know about this situation, it is challenging for us. They come to Bozburun and see that they will face such a thing, but as the operators, we find ourselves in a challenging situation.

Tourist Profile

DD: I remember the old times in Datça because I have been here since 81. There was this company, Sunsail. When Sunsail left Turkey, tourism, unfortunately, started to decline. The one and only Sunsail… I opened my business in 93, but Sunsail was here before. Thanks to Sunsail, all the companies in Datça, but chers, greengrocers, and restaurants revived. Datça was an entertainment center at that time; there were three discos, and now we don’t even have one open; we are losing our young people. There was a port by the sea; we call it a port because we don’t have a marina yet. Hopefully, they will build one. I mean, the port area was so active that all the young people would come here; some of them would sit there drinking their tea, some would drink beer, no one would interfere with anyone, and everyone was happy because they were making money. If people make money, there is peace. And you spend it accordingly.

AB: As you can see, everyone has fun fishing. People here haven’t abandoned fishing yet; there’s some farming, there’s olive farming. Some families in the upper neighborhood are still breeding livestock.

BK: The thing is, you can build buildings, you can make big hotels, but is it possible to do it here, right now? Even if I had the money and a place of my own, I’d have to deal with bureaucracy to build a big hotel. I couldn’t possibly do it. But one day, when I catch that loophole, it will become more accessible because of the supply-demand relationship.

RA: My friend did a lot of maintenance work on his boat last year. He’d be better off if he sold the boat, but it’s the same for all of us. We can’t sell our boats because of the supply and demand balance. You must find the extra money to sell your boat to get a new one. But if the balance is restored, you can sell your boat, get a new one and provide better quality service. You can build better ships, better equipped, with cameras underneath, to see under the sea. We can’t spend that much money; we’re trying to bring the ends together because tourism is limited.

SB: There is a spontaneous equilibrium; the capacity increases along with the number of beds. The same goes for second homes. Houses are built, and people keep coming. Someone buys a house, his relative follows, and his friend follows. This creates traffic in the restaurants and on the boats. People spend money here and there. Because tourism means money, it means a smokeless industry. There is such a balance, and there is a gradual increase. I don’t know if anyone will come for diving. We hear every year that diving boats will come. Let them come! They’ll have a blast of a time. But there’s still no sight of them.

4.1.2. Tourism Impacts and Residents’ Support

Economy vs. Ecology

RH: Some people moved to Datça 3–4 years ago. They chose Datça because it is calm and away from the city’s noise. People want Datça’s silence and calmness to remain intact; they do not want to have a marina or an easy access road, etc. This is where a dilemma arises: if we do not wish to make these investments, if we say that there should be no four-star hotels, no five-star hotels, no buildings, and no zoning, but still want to see Datça developing in terms of tourism, this is a dilemma. The more crowded a town becomes, the better the services are. I am not advocating that “We should be like Bodrum.” They are worried that we will be like Bodrum, but it’s an excellent line; I don’t think it can be arranged.

DH: Incentives should be given to encourage agriculture here. In other words, the state may support our youth. Why agriculture? There is a massive amount of arable land here… But they are empty, and they should be evaluated. People say the place was full of goats in the past, but now there are ten goats or fewer. Just think about it.

DD: When we started our business here in 1993, there was only one fisherman. We wanted him to bring us the fish he caught every day. When he caught a big one, he would not see a second fish because there was no need. So, he sold that one fish. At that time, there was not that much demand. Frankly, there were no restaurants. If you had a fish, you would sell it or eat it yourself. Fish were caught as needed. But nowadays, they overfish and throw them in the freezer. This does not make any sense when you can eat fresh fish.

AD: There is also the issue of selling fish here. For example, almost nobody brings fish to Bozburun Cooperative. However, if the fish has low economic value or there is an oversupply of fish, they give them to the cooperative or try to sell them directly to the yachts in the vicinity. There are even people who do a business out of it. The guy buys fish from the cooperative, takes it, and sells it as if he caught it himself.

VB: Marine traffic disturbs the seals. The seal is a timid animal; when there is any human activity, it goes away and generally does not use that area. This is the visible part, and we can also observe the megafauna. Since we can easily keep large marine animals such as dolphins, seals, and turtles, we can say if they occur or not. If they cannot be observed, it means that they are disturbed. They were here last year, but why not this year? You can attribute the direct cause to sea traffic or pollution etc. Each of these boats has at least ten guests; they serve food for ten people, resulting in incredible plastic pollution. Today, we dived into a Posidonia monitoring station and saw at least 10–15 plastic bottles. They pile up and smother an area, start to dissolve, and pollute that place. When these boats cannot find a place to discharge their waste at a certain point, they will discharge it into the sea when their tanks are full. Most of them just do it. The municipality tries to fight this problem with 3–4 boats, but they cannot catch up.

DAH: We must ensure that the boats do not moor around here because their anchors destroy the Posidonia meadows. They are very precious; you know we need to protect them. We have been dealing with this problem for quite some time. We can put an end to this problem by installing large mooring vaults. In the summer, far too many daily boats arrive, there is heavy traffic, and all the boats anchor in the bays...

MB: Rumors, unfortunately… The sea is getting polluted daily; there is nothing we can do. Most of the waste originates from land, but there has been incredible boat traffic recently. The more the place becomes popular, the longer the boats stay. We know that some ships stay in Selimiye, sometimes for a week, sometimes for 15 days.

UB: I don’t know much about the underwater, but the sea urchins have multiplied. They were not here at all, not even one. The sea is still clean and ruling. But if the problem continues with this pace, that is, if this is not prevented... Now I am dealing with the issue of waste disposal into the sea, individually and with the association. At the very least, we can raise awareness and educate people.

MK: I swear to God, 30 years ago, we would cook seafood on land and eat it after dipping it in the sea. You cannot do that right now. In other words, the sea is polluted, and detergents pollute the bays. You don’t see much out there, but for example, they dispose of much waste from the islands. Waste is released from Rhodes and Symi and enters the sea. Places with circulation are clean now, but much rubbish still flows into the sea. It would be better if it didn’t.

SB: This is one of the biggest problems of this year: Due to the pandemic, many people started to come to the region with their camper vans, as staying at a hotel or hostel was a little inconvenient. In other words, whoever turned a minibus into a camper van came to this region for vacation, frankly speaking, and they piled up in the parking lots even though it was forbidden. A place should have been allocated for camper vans, but this was omitted. There is a parking lot where the former teacher’s house was standing before demolishing. Plenty of camper vans parked there last summer. They dumped their wastewater into the sea in the late hours of the night. We just didn’t see it with our own eyes, but we think it’s done this way because there is no waste collection point in that area.

DH: although it has nothing to do with the sea, zoning is the most fundamental problem here. Land-based waste enters the ocean from here and there, and the sea gets polluted for this reason. It is our real problem, and it is terrible… They started building those one-bedroom flats and destroyed everything. Because eight one-bedroom apartments take up the same space as two large flats but require more parking space and produce more waste. There is not enough capacity to meet all that. Once all the available land was used downtown, they built one-bedroom flats in the villages. There were 5 thousand houses 5–6 years ago; now, there are probably more than 7 thousand. Construction, construction, construction! We have no other complaints.

RH: The society is divided between the locals of Datça and those who settled later.

Question: Do the people of Datça want tourists?

RH: Of course. If you think about it, you are here for 12 months; there is no one in winter! No tourism.

Migration

RA: People coming from outside of Datça have different profiles. For instance, they either sell their properties in Istanbul and come with a certain amount of savings or make an income by renting their property. I know the monthly payment of a few people from this profile, but one shouldn’t generalize. Some make a living by buying a field, putting a container there, and selling chicken eggs. There may be those who do not have much of an income. They make radical decisions. There is also a group of people who do not want a life with expensive phones or computers. They have given up electronics completely. But as I said, they have a house to rent or some income, but they live here or work from home. It’s widespread now. I know a lot of people who make internet sales from home. They earn their income from online sales. In any case, those who come here are not ordinary people; they are educated, speak foreign languages, and make a living by translating. So, what do they want from here? They want this place to remain; let them have peace of mind. They have no other expectations. But the locals here have different expectations. We must strike a balance. Of course, I am not talking about unplanned urbanization and growth without infrastructure. This is something that must be avoided, not only for Datça but for any place.

DH: There is this thought that one can work and take a vacation at the same time... Young people started to come; they wouldn’t come in the past; this was always a place for retired people. But life in big cities is very challenging now; it is difficult to find a job, or even if you can, the wages are meager. Many young people who wanted to live in a small place came here.

DD: Generally, businesses are run by outsiders. The summer season is hectic, and companies cannot catch up, so they hire staff from other cities. Some of my staff members are permanent… Why don’t the young people from the local community work? Because their parents have everything, fields, properties… Unfortunately, you cannot make them work.

AB: People who like it quiet and peaceful and retired people prefer this place because there are no nightclubs, therefore no young population. Young people who come here in the summer get bored. Nowadays, most of the visitors are from Istanbul. They come to Datça for a holiday to escape the Istanbul crowd. Just have a look at the natural beauty of this place. The air is always fresh because it is a peninsula. I believe the oxygen level is the second-highest globally, after Canada. The atmosphere here is perfect for asthma patients. Of course, there are shortcomings; we are a tiny town in the end. If we had a more planned way of growing, we could have been a more excellent town with fewer concrete structures. Measures have been taken for the future though; it would be more pleasing if we became a more excellent town.

4.2. Quantitative Findings

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geldmann, J.; Manica, A.; Burgess, N.D.; Coad, L.; Balmford, A. A Global-Level Assessment of The Effectiveness of Protected Areas at Resisting Anthropogenic Pressures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 23209–23215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spenceley, A.; McCool, S.; Newsome, D.; Báez, A.; Barborak, J.R.; Blye, C.J.; Bricker, K.; Sigit Cahyadi, H.; Corrigan, K.; Halpenny, E.; et al. Tourism in Protected and Conserved Areas amid The COVID-19 Pandemic. Parks 2021, 27, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroux, S.J.; Krawchuk, M.A.; Schmiegelow, F.; Cumming, S.G.; Lisgo, K.; Anderson, L.G.; Petkova, M. Global protected areas and IUCN designations: Do the categories match the conditions? Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauchald, O.K.; Gulbrandsen, L.H.; Zachrisson, A. Internationalization of protected areas in Norway and Sweden: Examining pathways of influence in similar countries. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2014, 10, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.unep.org/unepmap/who-we-are/barcelona-convention-and-protocols (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Tonazzini, D.; Fosse, J.; Morales, E.; González, A.; Klarwein, S.; Moukaddem, K.; Louveau, O. Blue Tourism. Towards a Sustainable Coastal and Maritime Tourism in World Marine Regions; Eco-Union: Barcelona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Y.; Gursoy, D.; Chen, J.S. Validating a Tourism Development Theory with Structural Equation Modeling. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Developing a Community Support Model for Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 964–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; So, K.K.F. Residents’ Support for Tourism: Testing Alternative Structural Models. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, S. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior to Explain the Effects of Cognitive Factors across Different Kinds of Green Products. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, F.V. Residents’ Opinions about the Sustainability of Tourism: Selimiye Village-Turkey. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 8, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://comdeksproject.com/country-programmes/turkey/ (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Okus, E.; Yüksek, A.; Yilmaz, I.N.; Yilmaz, A.A.; Karhan, S.Ü.; Öz, M.I.; Demirel, N.; Tas, S.; Demir, V.; Zeki, S.; et al. Marine biodiversity of Datça-Bozburun specially protected area (Southeastern Aegean Sea, Turkey). J. Black Sea Mediterr. Environ. 2007, 13, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://geka.gov.tr/uploads/pages_v/datcanin-sosyal-ve-ekonomik-durumunun-tespiti-kalkinma-stratejisi-ve-yol-haritasinin-belirlenmesi.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Bann, C.; Başak, E. Economic Analysis of Datça-Bozburun Special Environmental Protection Area. Project PIMS 3697: The Strengthening the System of Marine and Coastal Protected Areas of Turkey; Technical Report Series: 14; WWF Turkey: İstanbul, Turkey, 2013; pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Alrwajfah, M.M.; Almeida-García, F.; Cortés-Macías, R. The satisfaction of local communities in World Heritage Site destinations. The case of the Petra region, Jordan. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zhu, C.; Fong, L.H.N. Exploring Residents’ Perceptions and Attitudes towards Sustainable Tourism Development in Traditional Villages: The Lens of Stakeholder Theory. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publications Inc.: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, G.S.; Allen, C.R. Protected Areas as Social-Ecological Systems: Perspectives from Resilience and Social-Ecological Systems Theory. Ecol. Appl. 2017, 27, 1709–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, D. Sustainability and tourism: Reflections from a Muddy Pool. In Sustainable Tourism in Islands and Small States; Briguglio, L., Archer, B., Jafari, J., Wall, G., Eds.; Pinter: London, UK, 1996; pp. 69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorf, J. Towards New Tourism Policies: The Importance of Environmental and Socio-Cultural Factors. Tour. Manag. 1982, 3, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creaco, S.; Querini, G. The role of tourism in sustainable economic development. In Proceedings of the 43rd Congress of the European Regional Science Association: “Peripheries, Centres, and Spatial Development in the New Europe”, Jyväskylä, Finland, 27–30 August 2003; European Regional Science Association (ERSA): Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Nunkoo, R.; Alders, T. London residents’ support for the 2012 Olympic Games: The mediating effect of overall attitude. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Partnerships from cannibals with forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st-Century Business. Environ. Qual. Manag. 1998, 8, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.T.; Filimonau, V. A Recipe for Sustainable Development: Assessing Transition of Commercial Foodservices towards The Goal of The Triple Bottom Line Sustainability. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 3535–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.C.; Veiga, C.; Santos, J.A.C.; Águas, P. Sustainability as a Success Factor for Tourism Destinations: A Systematic Literature Review. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2022, 14, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, J.E.; Pollard, C.E.; Evans, M.R. The triple bottom line: A Framework for Sustainable Tourism Development. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2012, 3, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, K.; Camargo-Borges, C.; Eelderink, M. Exploring Participatory Action Research as a Driver for Sustainable Tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, B.S.; Klein, C.J.; Brown, C.J.; Beger, M.; Grantham, H.S.; Mangubhai, S.; Ruckelshaus, M.; Tulloch, V.J.; Watts, M.; White, C.; et al. Achieving the triple bottom line in the face of inherent trade-offs among social equity, economic return, and conservation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 6229–6234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, K.K.; Larson, L.R.; Powell, R.B.; Holland, W.H.; Allen, L.; Nabaala, M.; Nampushi, J. Impacts of Tourism on Support for Conservation, Local Livelihoods, and Community Resilience around Maasai Mara National Reserve, Kenya. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuščer, K.; Mihalič, T. Residents’ Attitudes towards Overtourism from The Perspective of Tourism Impacts and Cooperation-The Case of Ljubljana. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Mitchell. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Moritomo, M.; Woosnam, K.M. Residents’ Support for Sustainable Tourism Development in Rural Areas: The Case of Karuizawa, Japan. In Handbook of Research on Resident and Tourist Perspectives on Travel Destinations; Pinto, P., Guerreiro, M., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 88–114. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, P. Tourism Impacts, Planning and Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Akis, S.; Peristianis, N.; Warner, J. Residents’ attitudes to tourism development: The case of Cyprus. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Biran, A.; Sit, J.; Szivas, E.M. Residents’ Support for Tourism Development: The Role of Residents’ Place Image and Perceived Tourism Impacts. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalvelage, L.; Revilla Diez, J.; Bollig, M. Do Tar Roads Bring Tourism? Growth Corridor Policy and Tourism Development in The Zambezi Region, Namibia. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2021, 33, 1000–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raftopoulos, M. Rural Community-Based Tourism and Its Impact on Ecological Consciousness, Environmental Stewardship and Social Structures. Bull. Lat. Am. Res. 2020, 39, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Oré, E.M.; Custodio, M. Visitor Environmental Impact on Protected Natural Areas: An Evaluation of The Huaytapallana Regional Conservation Area in Peru. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 31, 100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comerio, N.; Strozzi, F. Tourism and Its Economic Impact: A Literature Review Using Bibliometric Tools. Tour. Econ. 2019, 25, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.X.; Jin, M.; Shi, W. Tourism as an Important Impetus to Promoting Economic Growth: A Critical Review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, S.; Alizadeh, V. The Economic Impact of The Lifting of Sanctions on Tourism in Iran: A Computable General Equilibrium Analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1221–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yergeau, M.E. Tourism and Local Welfare: A Multilevel Analysis in Nepal’s Protected Areas. World Dev. 2020, 127, 104744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, A.; Fanani, D. Examining Resident’s Perception of Sustainability Tourism Planning and Development: The Case of Malang City, Indonesia. Geo J. Tour. Geosites 2022, 40, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roney, S.A. Turizm Bir Sistemin Analizi; Detay Yayincilik: Ankara, Turkey, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tatoglu, E.; Erdal, F.; Ozgur, H.; Azakli, S. Resident Attitudes toward Tourism Impacts: The Case of Kusadasi in Turkey. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2002, 3, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntifering, J.R.; Linklater, W.L.; Naidoo, R.; ! Uri-≠ Khob, S.; Preez, P.D.; Beytell, P.; Knight, A.T. Sustainable Close Encounters: Integrating Tourist and Animal Behaviour to Improve Rhinoceros Viewing Protocols. Anim. Conserv. 2019, 22, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namberger, P.; Jackisch, S.; Schmude, J.; Karl, M. Overcrowding, Overtourism and Local Level Disturbance: How Much Can Munich Handle? Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 452–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canteiro, M.; Córdova-Tapia, F.; Brazeiro, A. Tourism Impact Assessment: A Tool to Evaluate The Environmental Impacts of Touristic Activities in Natural Protected Areas. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnet, D.; Jianmei, Y.; Dorji, T.; Qianli, X.; Lama, A.K.; Maowei, Y.; Shaoliang, Y. Bird Photography Tourism, Sustainable Livelihoods, and Biodiversity Conservation: A Case Study From China. Mt. Res. Dev. 2021, 41, D1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez del Rio-Vazquez, M.E.; Rodríguez-Rad, C.J.; Revilla-Camacho, M.Á. Relevance of Social, Economic, and Environmental Impacts on Residents’ Satisfaction with The Public Administration of Tourism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboglu, G.; Güçlüsoy, H.; Bizsel, K.C. Marine protected areas in Turkey: History, current state, and future prospects. In INOC International Workshop on Marine and Coastal Protected Areas; 2005; pp. 23–25. Available online: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/46125774/Marine_Protected_Areas_in_Turkey_History20160601-22062-fgk3c4-with-cover-page-v2.pdf?Expires=1667921733&Signature=fBKCM-59VEzps3nLHxJ83t6sTI00elMoM4HPgiNteQleuVXAmJveuIIvcs1y5PMsS5VvJXYlxozP9YNVUbm9oqoHGochc559VRAsR7aYxsJO7uXrOdacRBmajUvBrIgtXN3VMvrnR1BPZbhUM2gUSr3Clfw5KRn1-873itlZSvoEptxQ8UheQlMqs9wF9HvKM2DikevN7mXE1i8sSHfppS3v5iaUG~gYSwRlHqlgpQz9mxiuDjeDw1ppO286LSdV3lxRXDwozYpSh0qAaJ-FqNrSaJ~ajdhW5eMHe~YQuxHLMYYlcPPgcfL-goOK6jGjIYxQpTqn9BHaxuxf~vYklQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiogZuExPb7AhWLa8AKHR6ZBekQFnoECAgQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cbd.int%2Fdoc%2Fworld%2Ftr%2Ftr-nr-03-en.doc&usg=AOvVaw0cXeV0Fv0A7ndIERcF2xdR (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Bakır, S.; Mercan, E.G. Özel Çevre Koruma Bölgelerinin Küresel Koruma Pratiği Kapsaminda Değerlendirilmesi. In Proceeding Book, Proceedings of the Erasmus International Academic Research Symposum in Science, Engineering and Architecture, İzmir, Turkey, 5–6 April 2019; Asos Publications: İzmir, Turkey, 2019; pp. 725–740. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://ockb.csb.gov.tr/datca-bozburun-ozel-cevre-koruma-bolgesi-i-2747 (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Taşlıgil, N. Datça–Bozburun özel çevre koruma bölgesi ve turizm. Ege Coğrafya Derg. 2008, 17, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGehee, N.G.; Boley, B.B.; Hallo, J.C.; McGee, J.A.; Norman, W.; Oh, C.O.; Goetcheus, C. Doing Sustainability: An Application of An Inter-Disciplinary and Mixed-Method Approach to A Regional Sustainable Tourism Project. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, vii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral Collinearity and Misleading Results in Variance-Based SEM: An Illustration and Recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.B.; Areni, C. Affect and Consumer Behavior. In Handbook of Consumer Behavior; Robertson, S.T., Kassarjian, H.H., Eds.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1991; pp. 188–240. [Google Scholar]

- Rittichainuwat, B.; Rattanaphinanchai, S. Applying A Mixed Method of Quantitative and Qualitative Design in Explaining The Travel Motivation of Film Tourists in Visiting A Film-Shooting Destination. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| f | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 30.0 |

| Male | 70.0 | |

| Education | Primary | 20.6 |

| Secondary | 38.4 | |

| Higher | 39.4 | |

| Living in the region | 1–10 years | 35.4 |

| 11–20 years | 20.5 | |

| 21–30 years | 18.8 | |

| 31–40 years | 12.0 | |

| 41–50 years | 9.4 | |

| 51–60 years | 2.6 | |

| 61–70 years | 1.3 |

| Construct/Items | Mean | SD | Loadings | Cronbach Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic impacts | 0.765 | 0.850 | 0.588 | |||

| E1 | 4.570 | 1.067 | 0.814 | |||

| E3 | 4.599 | 1.145 | 0.821 | |||

| E6 | 4.731 | 0.983 | 0.673 | |||

| E7 | 4.735 | 0.903 | 0.751 | |||

| Social impacts | 0.744 | 0.841 | 0.639 | |||

| S2 | 2.828 | 1.169 | 0.857 | |||

| S4 | 3.023 | 1.194 | 0.786 | |||

| S5 | 3.259 | 1.203 | 0.751 | |||

| Environmental impacts | 0.615 | 0.751 | 0.505 | |||

| Cev1 | 2.152 | 1.160 | 0.784 | |||

| Cev4 | 2.628 | 1.226 | 0.596 | |||

| Cev5 | 2.634 | 1.176 | 0.737 | |||

| Cultural impacts | 0.717 | 0.840 | 0.641 | |||

| K1 | 3.291 | 1.120 | 0.848 | |||

| K2 | 3.492 | 1.069 | 0.885 | |||

| K4 | 3.657 | 0.965 | 0.648 | |||

| Residents’ support | 0.806 | 0.863 | 0.558 | |||

| D1 | 3.932 | 0.924 | 0.714 | |||

| D2 | 4.094 | 0.751 | 0.757 | |||

| D3 | 4.016 | 0.853 | 0.745 | |||

| D4 | 3.803 | 0.987 | 0.743 | |||

| D5 | 3.686 | 1.205 | 0.774 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural impacts | 0.800 | ||||

| Social impacts | 0.007 (0.098) | 0.799 | |||

| Residents’ support | 0.361 (0.446) | 0.169 (0.178) | 0.747 | ||

| Economical impacts | 0.455 (0.611) | 0.134 (0.188) | 0.371 (0.456) | 0.767 | |

| Environmental impacts | 0.365 (0.611) | 0.091 (0.182) | 0.233 (0.327) | 0.319 (0.523) | 0.710 |

| Relations | Β | t-Value | f2 | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic impacts → Residents’ support | 0.226 | 3.109 | 0.051 | Supported |

| Social impacts → Residents’ support | 0.134 | 2.056 | 0.022 | Supported |

| Cultural impacts → Residents’ support | 0.236 | 3.566 | 0.048 | Supported |

| Environmental impacts → Residents’ support | 0.063 | 1.010 | 0.020 | Rejected |

| Residents support Q2 = 0.098, R2 = 0.206 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sezerel, H.; Karagoz, D. The Challenges of Sustainable Tourism Development in Special Environmental Protected Areas: Local Resident Perceptions in Datça-Bozburun. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043364

Sezerel H, Karagoz D. The Challenges of Sustainable Tourism Development in Special Environmental Protected Areas: Local Resident Perceptions in Datça-Bozburun. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043364

Chicago/Turabian StyleSezerel, Hakan, and Deniz Karagoz. 2023. "The Challenges of Sustainable Tourism Development in Special Environmental Protected Areas: Local Resident Perceptions in Datça-Bozburun" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043364

APA StyleSezerel, H., & Karagoz, D. (2023). The Challenges of Sustainable Tourism Development in Special Environmental Protected Areas: Local Resident Perceptions in Datça-Bozburun. Sustainability, 15(4), 3364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043364