Abstract

Scholars have confirmed that apart from being an aid to hearing impaired or deaf people, intralingual subtitles, also known as captions, have a function as an audio–visual aid in language learning as well. While many studies verified the effect of using normal captions on various language skills such as listening, reading, comprehension, and vocabulary, little is known about the distinctive captions from Japan known as telop. This study tries to find out how Japanese language learners (JFL) feel about the use of open captions telop (OCT) (henceforth, telop) and what makes a lesson successful. Eight participants majoring in the Japanese language at Universiti Malaya were chosen to participate in this study and joined a lesson. During the lesson, they were asked to complete vocabulary tests, video analysis sheets, comprehension tests, and a learning diary. One interview was held to study their perceptions of OCT. The results show that there are five perceptions of the use of telop in JFL classrooms. We also found that there are four factors that can be addressed to make a lesson become successful. This study concluded that telop has many benefits that can help JFL learners improve their learning experience. Therefore, the use of telop by JFL instructors as an alternative way to expose authentic conversation to learners should be encouraged.

1. Introduction

Over the past three decades, the use of intralingual subtitles, mostly known as captions, as an audio–visual aid in language learning has garnered tremendous interest among many scholars and linguists around the world [1]. Despite its early function as subtitles for hard of hearing and deaf people (SDH) to help in understanding the content of television programs [2], studies conducted by language researchers have found it could also be used to assist second language (L2) learners to study foreign language via audio–visual material [3,4,5].

Since then, numerous studies have been conducted empirically to see the relation between watching videos with or without captions. For example, it has been confirmed that captions have various positive effects on nurturing various language skills such as vocabulary recognition, content comprehension, vocabulary acquisition, and listening [6,7,8]. This led to a consensus that watching videos with captions is more beneficial than without it.

From a dual coding perspective, Markham [9] suggested that the use of captions in facilitating first language (L1) and L2 comprehension can be conducted since standard features of videos nowadays are often supplied bimodally (visual and audio).

Moreover, it has been found that subtitles can improve student comprehension by acting as text information along with visual and audio information [10], and the use of the other features in captions such as colours and exaggerated tone in dialogue can attract attention from students to learn L2 [11]. Moreover, the use of captioned video increases learners’ motivation, enhances their cognitive processing, reinforces prior knowledge, and improves the skill of analysing language [8].

1.1. Research Gaps

Numerous studies about the effect of captions on language learning have shown positive effects [3,4,5,6,7,8]. However, several studies showed that captions could bring negative effects as well. For example, studies conducted by Taylor [12] found that captions brought distraction to lower-level learners. He argued that captions are a nuisance to beginners and made it challenging to follow visual, aural, and textual information at once. Zanon [13] and Zarei [3] also found that overcoming reliance on captions is difficult once students are familiarised with them and captions only slow down listening progress because students are ignoring the stream of speech.

To date, many precedent studies presented results based on experimental study comparing two or more groups [3,4,5]. Markham [9] argued that most studies used comparison such as using pre- and post-tests to measure the effectiveness of captions. This leads to the general conclusion that captions have benefits or vice versa without knowing how it works based on learners’ perspectives. Therefore, a study from different instruments such as learning diaries or interviews is needed to see whether captions could bring similar results or vice versa.

Another account that should be considered is how learners can learn from non-alphabet script language and how they process textual information in audio–visual (AV) material [8]. The use of captions as a supplementary tool for audiovisual (AV) content has become widespread [12], particularly in English as a foreign language (EFL) and English as a second language (ESL) Given that the majority of previous research has focused on English and other European languages, it is worthwhile to investigate its benefits in other languages, particularly Japanese.

Therefore, the current study investigates learners’ perceptions towards the use of distinctive captions from Japan called open captions telop (OCT) as a teaching tool in Japanese language classroom. This study will also examine factors such as video content and Japanese learning level that might help a lesson with telop to become successful. In order to achieve the purpose of this study, the researcher applied a qualitative approach as opposed to many previous studies that adopt a quantitative approach to measure the effectiveness of captions.

1.2. Research Questions

The current study addressed two research questions:

- How do JFL learners perceive learning Japanese through watching videos with telop?

- What factors need to be taken into consideration by instructors when using telop in the classroom?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definition of Subtitles and Caption

Numerous scholars have used different terms to refer to captions. To date, some studies used the term ‘subtitles’ as in ‘intralingual subtitles’ to refer to captions. For example, Zarei and Rashvand [4] used the term ‘subtitles’ and categorised subtitles as interlingual subtitles and intralingual subtitles. Interlingual subtitles refer to text that differs from the dialogues of the film; whereas intralingual subtitles are defined as subtitles that have the same language as the dialogues.

Szarkowska and Gerber-Morón [14] defined intralingual subtitles as captions used for transcribing the utterance of the speaker in a similar language (e.g., Japanese to Japanese); whereas interlingual subtitles mean a translation of spoken dialogue (e.g., Japanese to English).

Likewise, Markham [9] distinguished subtitles as text that appears in the native language with second language sound; whereas captions are defined as both text and sound in the same language. For example, if the audio in the native language is translated into text in the target language, it is called subtitles; on the other hand, if both audio and text are in the same language (the text is the transcription for the audio), it is called captions.

Therefore, subtitles can refer to a translation of dialogue into the target language in the form of text; whereas captions could be defined as a transcription of the dialogue in the same language in the form of text. In this study, the term captions will be used instead of ‘intralingual subtitles’ as suggested by Markham [9].

2.2. Previous Studies on Captions

Overall, numerous scholars agree that captions have a positive effect on enhancing students’ learning experience while watching audio–visual materials in the language classroom. For instance, in a precedent study, Bird and Williams [7] investigated the effect of captioning as a language learning tool by examining how a bimodal presentation can affect word learning. In their study, the group was shown a video with three conditions: (1) audio with captions, (2) audio without captions, and (3) captions without sound. They found that simultaneous presentation of audio with captions gave better results compared to other presentations. This result showed that the visual–cognitive system is indeed connected with the auditory–cognitive system as proposed by Paivio [15] in his Dual Coding Theory, where both auditory and visual systems are interconnected with each other when one processes information.

Markham [6] studied the effect of captioned videotaped on word recognition through listening. He presented two different educational videos with episodes to 118 university students studying English as a second language (ESL). Afterwards, a listening test consisting of multiple choices was given to students. He concluded that regardless of the content of the video, captions significantly improved students’ ability to recognise the words from videotapes and later through the listening test. In addition, they improve audio–visual comprehension and vocabulary development for students.

A study conducted by Zarei [3] on 90 undergraduate Iranian students who were divided into 3 groups also found similar findings. Each group was presented with nine episodes of the British comedy program Yes, Minister, but with different modes of captions. The first group watched the video with bimodal captions (English audio with English text), the second group watched with standard captions (English audio with Persian text), and the last group watched the video with reversed captions (Persian audio with English text). Two post-tests were administered consisting of 40 multiple choice vocabulary comprehension and another test consisted of 40 questions with blank space for vocabulary recall purposes. Results showed that the first group scored higher than the two other groups in both tests. This finding was in line with the result of Markham [6] above, where captions help students in vocabulary and listening. The author stated also that the type of captions, such as bimodal captions, has an influence in helping the first group to score higher in both tests rather than simply using random type of captions.

However, another study by Zarei and Rashvand [4] on the effect of subtitling and captioning video on vocabulary comprehension produced different findings. Thirty Iranian students taking English lessons in university participated in this study and were divided into four groups. Each group was shown the same film but with different conditions, (1) verbatim captions, (2) non-verbatim captions, (3) verbatim subtitles, and (4) non-verbatim subtitles. This study defined verbatim as text that copies everything from dialogue including prosody, sound effects, and pause fillers; while non-verbatim refers to text that summarises only necessary information. A post-test about vocabulary comprehension and production was conducted afterward. They found that non-verbatim groups were able to score in vocabulary comprehension tests higher than verbatim groups regardless of captions or subtitles. Nevertheless, captions are more favourable in vocabulary production tests in both verbatim and non-verbatim groups. This suggests that students may have similar scores regardless of what type of captions is used, which contradicts the earlier literature.

Another type of study conducted by Bensalem [5] investigated the effect of full captions (FC), keyword captions (KC), and no captions (NC) video on vocabulary acquisition. A total of 57 university students in Saudi Arabia taking English as a Foreign Language (EFL) participated in this study and were randomly assigned into three groups according to the aforementioned types of captions. The author presented a documentary video divided into three video clips and each video was approximately three minutes long. After watching the video, two post-tests about vocabulary recognition and meaning recall consisting of 12 target words that appeared in the video were administered. Results from the vocabulary recognition test suggest that FC helped the first group to score higher than KC and NC groups. Nevertheless, there was no significant result for the meaning recall test. The findings of this study showed that dialogue that is fully represented as text is better than keyword text.

Another captions study concerning the effect of captions on listening activities has been conducted by Winke et al. [8] on 150 students consisting of learners of Arabic, Chinese, Spanish, and Russian. Three short English documentaries were translated, transcribed, and dubbed into four respective languages in twelve videos. Participants then watched each videos with and without captions in their respective native language. After finishing the second viewing, participants were given two vocabulary tests and one comprehension test in English. Overall results from the tests showed that learners were able to understand better in video comprehension with captions.

2.3. Open Captions Telop (OCT)

Since the early 1980s, most television programs in Japan provide superimposed texts, mainly for displaying the name, karaoke lyrics, and program segments [16]. This superimposed text, called open captions telop (OCT), has become essential in Japanese television and always appears along with the speech of the host, narrator, and interviewees in a variety of shows and news programs.

Telop is an abbreviation term for a television opaque projector, which was previously used mainly to project texts onto images on the TV screen [2]. Telop is different from the normal captions that appear in Western television programs where it mainly functions as an aid to support the deaf or hard-of-hearing (known as subtitles for the deaf or hard-of-hearing (SDH) [17]. Byran Hikari [18] explained that the functions of telop are not limited to clarifying and deciphering difficult speech for older and foreign viewers only; it is used for commentating dialogue as well as emphasising a part of the speech or discourse through different colours, fonts, and sizes.

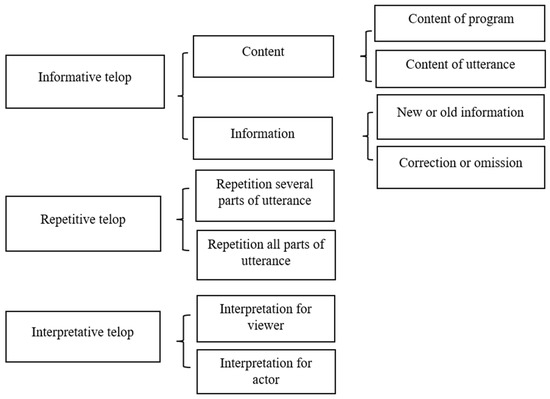

According to Shiota [19], telop can be divided into three parts, as shown in Figure 1. The first one is informative telop, which is mainly for clarifying the content of the program or spoken dialogue. It is also used to explain any new or old information as well as working as correction or omission during the show. The second part is repetitive telop, mainly used for showing a part of the speech or all utterances spoken in the dialogue. The characteristic of this telop is that it shows the exact transcription of what viewers are listening to. The last part is interpretative telop, which is intended to explain non-verbatim or psychological behaviour for viewers to understand the situation or scene in the program.

Figure 1.

Telop taxonomy. Adapted and translated from Shiota [19].

In this study, all types of telop that appeared in the videos were used as a teaching tool in the JFL classroom. All telops observed by the participants in the videos are categorised into themes and analysed.

3. Methodology

3.1. Design

The current study employed a qualitative method to explore the phenomenon of using telop as a teaching tool in the Japanese as a foreign language (JFL) classroom. According to Goes [20], phenomenology design is suitable for addressing an obscure research problem/solving problems when little evidence exists in the literature. In addition, van Manen [21] also argued that not only do many phenomenological researchers conduct research interviews to explore the phenomenological problem; they seldom do observation on study sites to avoid any non-logical or non-cognitive factor that exists in the qualitative phenomenological study. Therefore, the researcher employed the qualitative phenomenological design for this study.

3.2. Participants

The current study involved eight Malaysian participants, consisting of first-to-third-year students from the Faculty of Languages and Linguistics in Universiti Malaya. They are all majoring in the Japanese language and have a range of ages from 21 to 26 years old. Of the 8 participants, 7 were females and 1 male.

3.3. Material

The materials used for this study were taken from a regular Japanese TV program, Potsun to Ikkenya (A house in the middle of nowhere). Potsun to Ikkenya is a Japanese TV variety show that showcases Japanese people living in remote areas and is popular with an average viewer rating of 11.8–13% and ranked #1 in November 2019. The footage used in the study was taken from a 28 July 2019 episode and was sourced from the official streaming website TV GYAO, with the original one-hour footage cut into two 3–4 min clips. The clips featured a married couple who lived in a remote area as farmers and showed their reasons for living there and how they survived on their own. The videos were chosen for their clear language and abundance of repetitive and interpretive telop.

3.4. Instrument

3.4.1. Learning Diaries

The present study used learning diaries to record the progress of students. As Yi [22] noted, diaries can not only be used to make students aware of how they learn; they can also can be used as an assessment for teachers to reflect on one’s lesson. Therefore, for this study, students were allowed to write freely about the video and captions that they have watched in class. The example of the diary is given in the Appendix A.

3.4.2. Video Analysis Sheet

As a lesson activity, the students analysed the telop from the above video. This activity aimed to test their awareness of all the information going on in the video, as well as how they perceive the content of the videos. According to Vanderplank [23], students who took notes while watching videos with subtitles can acquire more accurate results because they retained the specific language used in the video. Students were then allowed to take notes freely about the peculiarities of the language and the cultural aspect, as well as what they thought about the history. The detail of the sheet can be found at Appendix B.

3.4.3. Interview

All participants were asked about their experience watching the videos and their responses to telops that were presented on the video to examine how they deal with captions and how they feel when captions appear on the screen. The question interview was adapted from Winke, Gass, and Sydorenko [8]. The following questions were asked:

- What do you think about the video? Do you think it is interesting?

- What do you think about the telop in the video?

- Do you think telop is a hindrance or essential for you when you watch the video?

- Do you think telop could help Japanese learners to learn Japanese?

- After you experienced this class, do you agree that it should be used to teach Japanese in class in the future?

- Overall, what is the impact of telop on your Japanese study?

In addition to these questions, several questions have been created and were asked directly to participants personally. These personal questions acted as follow-up questions based on their answer in the learning diary and video analysis sheet.

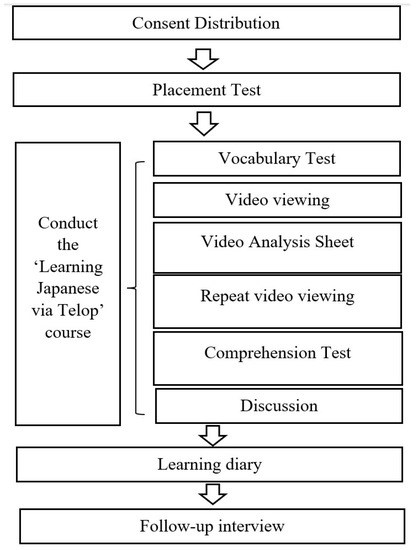

3.5. Procedure

The process began with the distribution of consent forms to all students who were majoring in the Japanese language in the Faculty of Language and Linguistics, University Malaya. Of the 42 students, however, only 8 students voluntarily joined the study which consisted of 4 third-year students, 3 second-year students, and 1first-year student. Next, the researcher administered two short 10-question multiple-choice tests to determine their language proficiency due to the gap in the year of their study. The first 10 multiple-choice test was a vocabulary test, and the latter was a listening test. Both tests were taken from the Japanese Language Proficiency Test (JLPT) N3 2018. JLPT mainly has 4 tests: listening, vocabulary, grammar, and reading. It has 5 levels, where N5 is the lowest and N1 is the highest. JLPT N3 was chosen because its level is intermediate.

The purpose of vocabulary tests is to determine the subjects’ vocabulary level since some of the telops may be beyond their language level. Hartono and Prima [24] found in their study that inadequacy of vocabulary capacity can potentially inhibit learner’s learning experience, especially in reading practice. Meanwhile, some information in the video might not be written in telops. Hence, participants need to listen to the audio carefully to understand the content of the video. Therefore, the listening test JLPT N3 was administered. All participants passed both tests.

The researcher then conducted an online lesson called “Learning Japanese via Telop” after one week. This lesson took 120 min and was conducted fully in Japanese, but English and Malay languages were used to explain some parts of the video. The researcher started with a brief explanation of the course and its assessment for 20 min. After that, participants were asked to complete 10 vocabulary questions that were taken from the video with answers of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. They can only answer ‘Yes’ if they are familiar with the writings, meanings, and pronunciations. Therefore, if they know only one criterion, they will be considered unfamiliar with the words and must answer “No”. The reason behind this detail of questions was that Chinese students who knew Chinese characters could understand without even knowing their pronunciations. This test was administered in 5 min. Later, participants were shown video 1 in 5 min. After finishing watching the video, they were asked to fill out the video analysis sheet where participants wrote about what they learned during the viewing; for example, language skills (e.g., vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation), culture, and the content and morals from the video. This activity took 10 min, and all answers were submitted via Google Classroom.

Participants were then instructed to watch the first video. As Cakir [25] suggested in the repetition activity, this was conducted to let participants confirm what they have listened and read since they might miss essential information during the first viewing. Afterward, one ten-minute comprehension test consisting of 10 multiple choice questions was administered. This test was to examine whether telop provides sufficient information for students to understand the video or vice versa. After that, the researcher conducted a short discussion and reflection with the participants. The researcher explained any information or details that they missed or did not understand. After watching the first video, all activities were also applied to the second video, with a 10 min recess between discussion of the first video and the second video viewings. At the end of the session, participants were assigned a learning diary in which they had to write a summary of their learning. The learning diary examines participants’ perceptions of lessons as well as a lesson reflection. Participants could write in Malay, Japanese, or English.

The researcher held an online follow-up interview via Google Meet one week after a lesson. To explore more about the subjects’ feelings and ideas, follow-up questions were created prior to the writing of the subjects’ thoughts in their learning diaries and video analysis sheets. The questions used in the interview were planned as semi-structured questions and were conducted in a group. These interviews were recorded and transcribed for later analysis.

The design of the study was planned as follows (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The flow of procedure in this study.

4. Findings and Discussions

In this study, data was collected using a video analysis sheet, a learning diary, a vocabulary test (pre), a comprehension test (post), and a follow-up interview. However, it is important to note here that the pre-test was different from the post-test; the former was held in a vocabulary test and the latter was administered in a comprehension test. Because the goal of this study is not to generalise the findings based on tests versus previous literature, a comparison to see if telop improved learning will not be considered. Participants’ responses in the video analysis sheet, learning diary, and follow-up interview were taken to triangulate data for analysis. It should also be noted that the written responses from participants in the analysis sheet and learning diary were varied and some participants changed their thoughts during follow-up interview sessions. Through three types of data collection, several underlying findings have emerged from participants’ comments and have been identified as themes through the thematic analysis process. The thematic process was adopted from the general inductive approach by Thomas [26]. This approach is suitable for inexperienced qualitative researchers as it guides them with precision in the generation of themes from raw data and the process of more specific categorisation.

The analysis process began with data collection from video analysis sheets, learning diaries, and interview transcription. The researchers then read through the data several times to become acquainted with it. Then, based on their frequency and similarity, several keywords were identified as themes. Under the language feature theme, for example, the words ‘vocabulary,’ ‘kanji,’ and ‘words’ were listed and labeled. NVIVO software was used for all processes. For the confidentiality purpose, all the participants were given numbers P1 to P8. Quotes from participants were also copied exactly without changing their grammar structures or vocabularies. Quotes that were written in Japanese and Malay were glossed in English by the researcher.

4.1. Perceptions towards the Use of Telop as a Teaching Tool in JFL Classroom

To answer research questions, the general inductive approach by Thomas [26] was used to observe the most prominent data to be categorised into themes. There are five themes that emerged in the answers to RQ1, recorded as follows.

4.1.1. Language Features

Overall, all participants agreed that telop assisted them in terms of vocabulary learning, kanji (Chinese characters) learning, and pronunciation.

| P1 | I do agree that telop can increase our vocabularies through immersive method, instead of just learning and memorizing vocabs purely on its own through dictionary. In this way, we can gain a more natural understanding through real life usage of vocabs and idioms. | Learning diary |

| P3 | I think it’s more helpful in term of kanji because we get urm, because it’s like using your unconscious mind to actually grasp the reading as you read the video. | Interview |

| P5 | For me la, yeah, through telop they can introduce a lot of new kanjis that you may not see, I mean like textbook and one’s note, maybe stuff from like newspapers yang (that) high level yang (that) won’t usually come out unless you search for yourself la. So, to me telop kanji is right really useful in term of learning. | Interview |

| P6 | 語彙の方が多いと思います。例えば、この前「地震」しか知っていませんでしたが、今も「震災」という言葉が知るようになりました。 I think there are a lot of words. Previously I only knew the word 地震(jishin)—earthquake, but now I got to learn there is a word 震災(shinsai)—disaster as well. | Worksheet 1 |

| P7 | 授業のビデオを通して、聴解力と読解力が練習できると思います。と言うのも、私たちはビデオの中のテロップを見ると聞いたことが確認できるからです。 Through video from the lesson, I think it can be a practice for listening and comprehension skills. In other words, it is because we can confirm what we have heard by seeing telop. | Learning diary |

The abovementioned findings confirmed the result from Bird and William [7] and Zarei [4], where vocabulary has become a prominent feature in language learning through the captions. Meanwhile, some participants also stated that telop is more helpful in terms of kanji learning. From this study, it is understood that there are a lot of kanji expressions that can be taught in addition to what is learned in a classroom. Many words in Japanese are similar to each other in pronunciation; for example, the words with the same pronunciation but with different meanings 強化/kyouka/strengthening and 教科/kyouka/subject. By viewing at telop, Japanese learners would be able to confirm the word’s correct pronunciation as well as its writing.

4.1.2. Telop Acted as Visualizing the Spoken Discourse to Verify the Audio

Continuously, one of the emerging themes is that telop can assist as an audio visualiser. It means that any spoken dialogue in the video could be viewed in the form of text. Furthermore, since kanji are logographic characters [27,28], this can help students to understand the meaning of kanji even without knowing how to pronounce them.

| P1 | For me I think it’s essential because it can help us to comprehend the content of the video better. Because when just listening we sometimes, because we are not, we’re non-native Japanese speakers right? So, when just listen we get only catch word, their word is saying…what they’re saying. So telop I think that at least we have a visual presentation of the word. | Interview |

| P7 | I also think it’s very helpful because like we cannot sure what we hear is correct but through the telop we can know. | Interview |

4.1.3. Emphasizing the Sentence for Focus

As mentioned in Section 2 above, telop has various fonts, colours, sizes, and shapes to attract the viewers’ attention to the text [29]. Previous studies have also confirmed that this is a new way to manipulate viewers’ understanding of content [2]. In contrast, interestingly, telop could be used here to make learners aware of what they should be looking at. By looking at such a preference for telop, learners could focus directly on what information they should extract, rather than finding information all over the screen.

| P6 | I cannot understand very few la, but if got the telop it can emphasize the content that it wants to convey, so yeah I think that … benefit of telop. | Interview |

| P6 | テロップで表しない語彙より、テロップで表す語彙の方が印象深かったと思います。 Words that are shown by telop have a deep impression rather than those not indicated by telop. | Learning diary |

4.1.4. Advance Learning

Meanwhile—and might be the most interesting theme that emerged from the analysis—the author found that telop could function as a means through which to learn new grammar, vocabulary, sentence structure, and pronunciation in advanced learning. This could be a new benefit, especially to beginning and intermediate level Japanese learners. Even though they would face difficulties such as difficulty understanding or missing the spoken dialogue, telop would offer them a second chance as it shows the spoken dialogue in the form of text.

| P8 | From the video, I get to see how the sentence structure is written in parts where I have not learnt yet in class. | Worksheet 1 |

4.1.5. Differentiate between Japanese and Chinese Writing

While this theme might not be relevant to non-Chinese learners, the findings found that the advantage of kanji when studying Japanese are not necessarily evident. Kanji was imported from China to Japan in the 5th century and it has gone through a long process of assimilation into Japanese. Some meanings were changed and are totally different from the original Chinese kanji. During video viewing, one Chinese participant said that she could not expect the original meaning of the word 留守/rusu to be changed from stay behind to absence. For instance, the word 勉強/benkyou/’study’ in Japanese would be mistaken by the Chinese as a strong force since the kanji of 強/kyou/or/tsuyoi/’strong’ is included in the word.

| P6 | Urmm… not really big different for some but some meaning is different, like totally different, just like the benkyou (study), yeah and the rusu (absence) also. | Interview |

4.2. Considerations for JFL Instructors

Similar to the previous RQ1 question, several themes were identified by the researcher after going through a strict selection process. These emergent themes were taken from the data in concordance with participants’ suggestions, ideas, criticisms, and feelings. There are four themes that emerged to address RQ2.

4.2.1. Interest and Motivation

One of the important aspects of encouraging participants to be immersed in the lesson is their interest in the topic itself. Without interest, students tend to lose their motivation, and lessons may become dull or less effective. Hence, it is understood that in order to trigger the facilitation of study, this most basic requirement must be fulfilled.

Generally, participants had shown positive responses to using telop in the classroom as a medium for teaching.

| P1 | It’s definitely an interesting way of vocabulary learning, and I do hope that my own Japanese vocabulary skills will increase throughout joining in this class. | Learning diary |

| P2 | For me, watching videos for learning Japanese is fun, as I don’t really watch this kind of program. From these videos I get to hear the real life japanese conversation which I think is good for my listening skills as well. | Learning diary |

| P8 | After experiencing the class for the first time, I find the class quite interesting as it sort of challenges my knowledge in the Japanese language especially in terms of vocabulary. | Learning diary |

4.2.2. Class Activities

Cakir [25], in his review study on the use of audio–visual aids in foreign language study, stated that in order to establish a successful learning environment, teachers or instructors have to take responsibility for making the class become active and meaningful. He suggests some activities such as active viewing, repetition, reproduction activities, and follow-up activities are suggested. Under this theme, however, suggestions and criticisms from participants are included for future reference.

| P1 | I think like at very, at the very least maybe we can some kind of context like what this topic is about before we watch the video. | Interview |

| P3 | I think the lesson has potential and could be executed successfully but, just like any medium, it must come with adequate explanation. | Interview |

| P5 | I think there is a need to be a level of interaction from, input from lecturer that themselves so that you know they can guide the students to what to be focused on. | Interview |

| P7 | I don’t think people can remember this by watching in short time. But have to stop and write it on. | Interview |

4.2.3. Student’s Competency

Studies on captions have shown that different levels of competency in language ability brought different results [30,31,32]. For instance, Birulés-Muntané and Soto-Faraco [31], in their study on the effect of captions in English spoken films, found that intermediate-to-advanced learners gained the greatest benefit when exposed to captions while viewing the film. Similarly, Vanderplank [32] only accepted those who are roughly intermediate or slightly above in his C-test for research on attitudes and strategies among thirty-six learners of four different languages; as he explained, those at the beginner level might receive no or little input from watching the film with captions. Therefore, a similar setup in this study is employed.

| P4 | 中間レベルも大丈夫ですけれども、でもそのビデオの内容もなんかちょっと高い。だから初心者に対してちょっと難しいと思います。 I think for intermediate level, it is still acceptable but a little bit difficult for beginner level since the content (level) in the video is high | Interview |

| P8 | I somehow was able to read some of the captions, but at times, I still find it difficult to read due to the lack of knowledge on some of the kanji used in the video | Learning diary |

4.2.4. Technical Considerations

Lastly, another critical point that educators need to be aware of is the potential for technical problems. Aside from common issues such as internet connection, sound system, graphic resolution, and the usage-time capability of video conferencing software such as Google Meet and Zoom, this study has shown that other technical issues, such as speed, voice, and pace during the lesson in particular, need to be considered as well.

| P1 | I think 3 min should be enough, because the longer might be, it’s harder for a student to obtain the information of the video. | Interview |

| P7 | ビデオの速度とペースは、単語の意味を正確に知るのは少し速いかもしれません。 Perhaps it is a little bit fast to know exactly the meaning of some words with the speed and pace of videos. | Learning diary |

| P8 | I would appreciate it if the class is not carried out to late in the evening as I tend to lose focus and interest easily during these times especially around 3 pm | Learning diary |

5. Conclusions

This study examines the use of telop as a teaching tool in JFL classrooms in Japanese language learning. As explored in the literature review, the assistive capacity of the telop in its application to language learning is significant. Moreover, as it turned out, the use of telop in Japanese not only helps students to read or pay attention to captions; it also captures their attention, which is especially important in learning a foreign language.

Five themes emerged from participants’ perceptions of the use of telop in the Japanese language classroom and there are four factors that instructors need to consider before they can execute Japanese lessons using telop as a medium of teaching.

Despite a small sample from one institution, the results from the current study confirmed that watching videos with telop can be used as an alternative way to expose Japanese learners to authentic Japanese conversation. In fact, scholars have also suggested that exposure to natural language settings could facilitate successful foreign language learning [33,34,35,36]. Hence, with the current pandemic rampaging, exposure to authentic material could be conducted online as information is easily accessible. Furthermore, nowadays, learners have more tendency to search for additional information from the internet on their own to increase their knowledge. With such a trend, it is also safe to posit that switching from traditional learning to this self-initiated method could increase students’ motivation to learn JFL as it can attract learners’ attention toward learning.

Meanwhile, telop not only confirms the meaning of the interlocutors but also aids in recognising new words learned through video—particularly in terms of kanji learning—for those who are unfamiliar. Telop is also helpful for people who know how to read the Chinese version of kanji as text; it makes students aware of the differences in meaning and use between Chinese and Japanese kanji. Telop also benefits those who are familiar with the Chinese version of kanji in text form, making students aware of the differences in meaning and application between Chinese and Japanese kanji. In the case of words that appear identical but differ in word order, such as 運命/unmei/destiny and 命運/mei’un/fate (the latter of which can only be used when life or death is at stake), Chinese learners may not be aware of the true meaning unless they consult a dictionary. Keeping this in mind, they will be able to enhance their kanji comprehension and application via telop.

In conclusion, there are many benefits of telop for Japanese language learners. Videos with telop help learners improve their Japanese and increase engagement. Watching Japanese videos is good for understanding the situational adaptability of using standard and casual language and knowing when and when not to use certain words. At the same time, using telop to teach the Japanese language should be encouraged by Japanese language instructors as the findings prove that telop can improve learners’ literacy in areas such as kanji reading, boosting learners’ focus, and meaning guidance in Japanese. Although it is nearly impossible to teach only via telop in, it is hoped that it can be used as an alternative way to expose learners to natural by attracting their attention to the content of the videos.

6. Limitation and Future Research

This study had a number of limitations. First and foremost, the sample size was insufficient, and it was drawn from the same population of interest. Consequently, the findings of this study cannot be generalised. Second, only one video genre was presented to the participants. There is a possibility that utilising telop for the study of a foreign language could yield varying results for different genres. Lastly, the test results were not presented in this study due to the small sample size. Therefore, it is impossible to quantify the improvement of participants’ language skills.

For generalisation purposes, it is suggested that, in future research, the sample size should be greater than 30 individuals. Additionally, a mixed-methods study could be conducted to determine the relationship between quantitative and qualitative data when using telop to learn Japanese. Similarly, many Japanese television programmes, such as news and music videos, display the telop on the screen. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate other genres to determine whether telop can influence Japanese learning. Even though many studies place a great deal of emphasis on pre-tests and post-tests, it cannot be denied that this test method could be used to measure the improvement before and after studying Japanese with telop. For future research, a comparison by means of tests is therefore suggested.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A., T.M. and N.L.W.; Methodology, K.A., T.M. and N.L.W.; Software, K.A.; Validation, Y.T.P.; Formal analysis, K.A., T.M. and N.L.W.; Investigation, K.A., T.M. and N.L.W.; Resources; K.A.; Data curation, Y.T.P.; Writing-original draft preparation, K.A., T.M. and N.L.W.; Writing-review and editing, Y.T.P.; Visualization, K.A.; Supervision, T.M. and N.L.W.; Project administration, Y.T.P.; and Funding acquisition, Y.T.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Mapua University Directed Research for Innovation and Value Enhancement (DRIVE).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, Universiti Malaya Research Ethics Committees.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the respondents who answered our online questionnaire. We would also like to thank our friends for their contributions in the distribution of the questionnaire.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Learning Diary

This learning diary purposely created to explore your opinions or insights about the lessons. Your comments or criticisms will help me to understand how we can improve this lesson for the future. What you will write in this diary will be confidential and researcher only uses it for study purpose. Please try to be honest how you feel and explain in detail even it might be difficult to express. You can write your diary in Malay, English or Japanese.

If you don’t know what to write in diary, here are some questions to ponder to help you in writing the diary (not limited to only these topics)

- What do you think about the lesson?

- How do you feel in that lesson?

- Was everything in the class going well or bad?

- What do you think about activities?

- What did you learn from Japanese caption?

- Were you able to read the caption or miss all the time?

- What is the impact of telop on your Japanese study?

- Do you have any suggestion for future reference?

| Name | |

| Year | |

| Matrix Number | |

Appendix B. Video Analysis Sheet

| Video Title | |

| Language 文法(ぶんぽう) (grammar), 語彙(ごい) (lexicon), 擬音語(ぎおんご) (onomatopoeia), 擬態語(ぎたいご) (phenomime), ことわざ (proverb), 方言(ほうげん)(dialect) など (etc.) | (e.g., what did you learn about language from the video) |

| Culture/Lifestyle 登場人物(とうじょうじんぶつ)の生活(せいかつ), 生き方・文化(ぶんか)など (Life of the characters, way of life, culture etc.) | (e.g., what did you learn about their lifestyle) |

| View 価値観(かちかん)・意見(いけん)・批評(ひひょう) (Values, opinions and criticism) | (e.g., what do you think about their story?) |

References

- Vanderplank, R. The value of teletext sub-titles in language learning. ELT J. 1988, 42, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hagan, M. Japanese TV entertainment: Framing humour with open caption telop. Transl. Humor Media 2010, 2, 70–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zareei, A.A. The effect of bimodal, standard, and reversed subtitling on L2 vocabulary recognition and recall. Pazhuhesh E Zabanha Ye Khareji 2009, 49, 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Zarei, A.A.; Rashvand, Z. The effect of interlingual and intralingual, verbatim and nonverbatim subtitles on L2 vocabulary comprehension and production. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2011, 2, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensalem, E. The efficacy of captions on students’ incidental vocabulary acquisition. J. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markham, P. Captioned videotapes and second-language listening word recognition. Foreign Lang. Ann. 1999, 32, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, S.A.; Williams, J.N. The effect of bimodal input on implicit and explicit memory: An investigation into the benefits of within-language subtitling. Appl. Psycholinguist. 2002, 23, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winke, P.; Gass, S.; Sydorenko, T. The effects of captioning videos used for foreign language listening activities. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2010, 14, 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Markham, P. The influence of culture-specific background knowledge and captions on second language comprehension. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2001, 29, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltova, I. Multisensory language teaching in a multidimensional curriculum: The use of authentic bimodal video in core French. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 1999, 56, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrani, T.; Soltani, R. The pedagogical values of cartoons. Res. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2011, 1, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, G. Perceived processing strategies of students watching captioned video. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2005, 38, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanón, N.T. Using subtitles to enhance foreign language learning. Porta Ling. 2006, 4, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Szarkowska, A.; Gerber-Morón, O. Viewers can keep up with fast subtitles: Evidence from eye movements. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199331. [Google Scholar]

- Paivio, A. Mental Representations: A Dual Coding Approach; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sasamoto, R.; Doherty, S. Towards the Optimal Use of Impact Captions on TV Programmes. 2016. Available online: https://doras.dcu.ie/26623/1/Sasamoto_Doherty%202016_preprint.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- O’Hagan, M.; Sasamoto, R. Crazy Japanese subtitles? Shedding light on the impact of impact captions with a focus on research methodology. Eyetrack. Appl. Linguist. 2016, 2, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Hartzheim, B.H. Inside the Media Mix: Collective Creation in Contemporary Manga and Anime. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shiota, E. 関連性理論とテロップ の理解 [Relevance Theory and Understanding of Telop]. J. Ryukoku Univ. 2003, 31, 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- Goes, J. When and When Not to Use Phenomenology. Available online: http://www.dissertationrecipes.com/when-and-when-not-to-use-phenomenology (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Van Manen, M. Transdisciplinarity and the new production of knowledge. Qual. Health Res. 2001, 11, 850–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J. The Use of Diaries as a Qualitative Research Method to Investigate Teachers’ Perception and Use of Rating Schemes. J. Pan-Pac. Assoc. Appl. Linguist. 2008, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderplank, R. Paying attention to the words: Practical and theoretical problems in watching television programmes with uni-lingual (CEEFAX) sub-titles. System 1990, 18, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartono, D.A.; Prima, S.A.B. The correlation between Indonesian university students’ receptive vocabulary knowledge and their reading comprehension level. Indones. J. Appl. Linguist. 2021, 11, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakir, I. The use of video as an audio-visual material in foreign language teaching classroom. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol.-TOJET 2006, 5, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.R. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, M.A.K. Spoken and Written Language; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Rasiban, L.M.; Sudana, D.; Sutedi, D. Indonesian students’ perceptions of mnemonics strategies to recognize Japanese kanji characters. Indones. J. Appl. Linguist. 2019, 8, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasamoto, R.; O’Hagan, M.; Doherty, S. Telop, affect, and media design: A multimodal analysis of Japanese TV programs. Telev. New Media 2017, 18, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matielo, R.; D’Ely, R.C.S.F.; Baretta, L. The effects of interlingual and intralingual subtitles on second language learning/acquisition: A state-of-the-art review. Trab. Linguística Apl. 2015, 54, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birulés-Muntané, J.; Soto-Faraco, S. Watching subtitled films can help learning foreign languages. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderplank, R. ‘Gist watching can only take you so far’: Attitudes, strategies and changes in behaviour in watching films with captions. Lang. Learn. J. 2019, 47, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, N.C. Second language acquisition. In Oxford Handbook of Construction Grammar; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vulchanova, M.; Aurstad, L.M.; Kvitnes, I.E.; Eshuis, H. As naturalistic as it gets: Subtitles in the English classroom in Norway. Front. Psychol. 2015, 5, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.; Wong, N.; Ng, L. Japanese language students’ perception of using anime as a teaching tool. Indones. J. Appl. Linguist. 2017, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, L.S.; Hashim, H. The usage of mall in learners’ readiness to speak English. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).