Are Librarians Ready for Space Transformation? A Systematic Review of Spatial Literacy for Librarians

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Q1: What kind of spatial literacy should librarians possess?

- Q2: What is the current status of spatial literacy among librarians?

2. The Connotations of Spatial Literacy for Librarians

2.1. Spatial Literacy

2.2. Components of Spatial Literacy

2.3. Spatial Literacy for Librarians

3. Methods

3.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

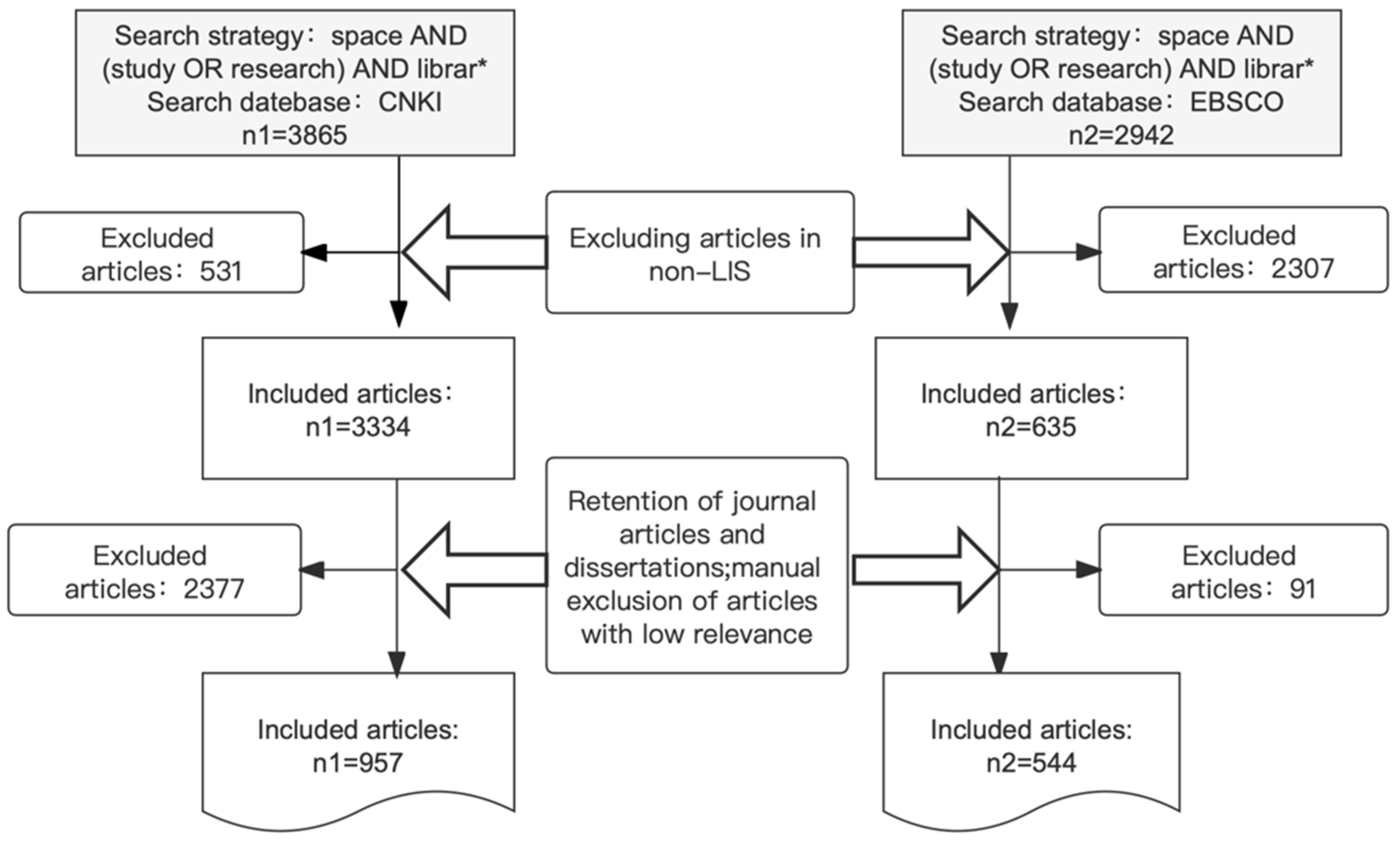

3.2. Literature Search and Study Identification

3.3. Data Screen and Extraction

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

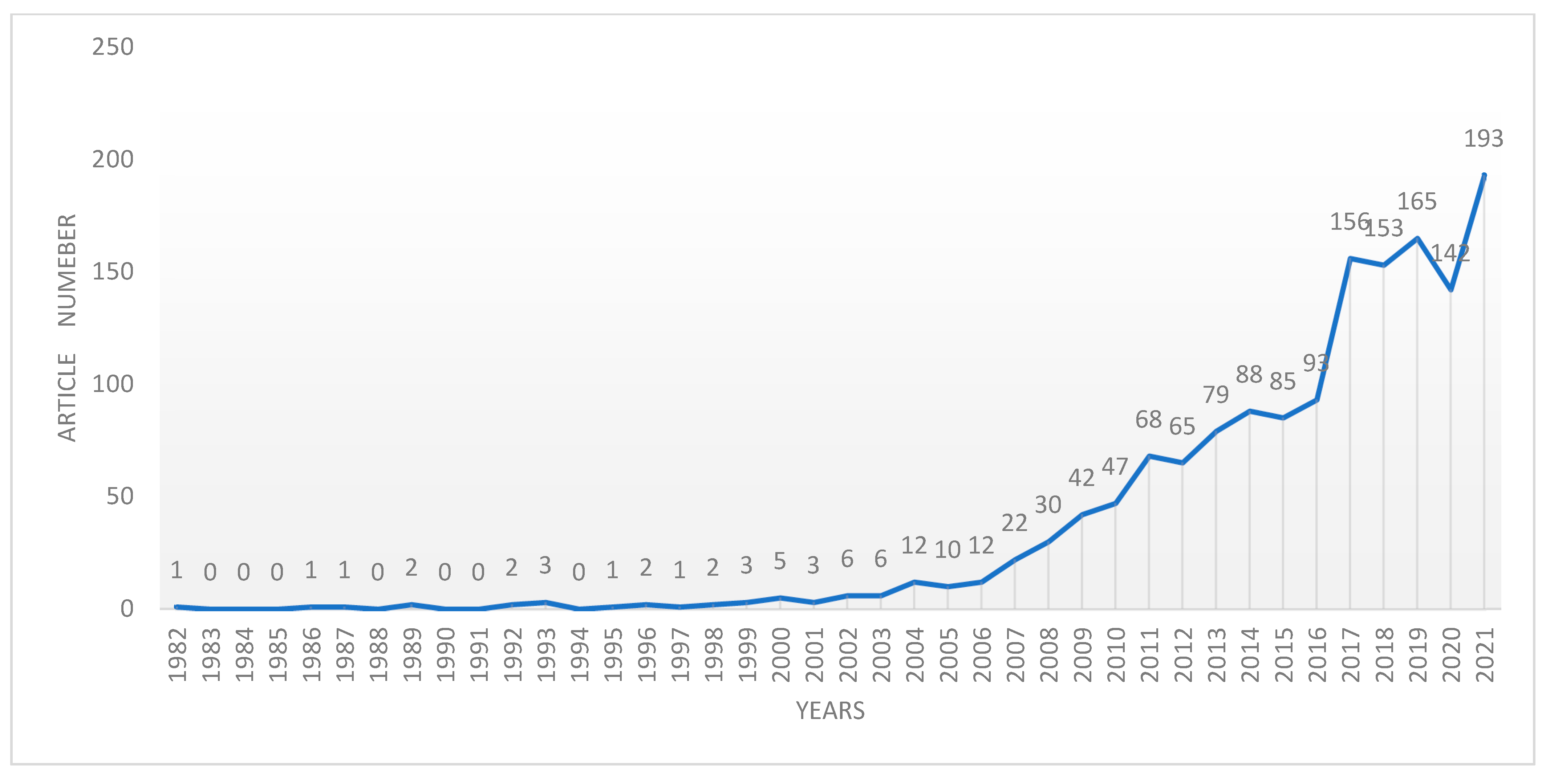

4.1. Number of Literature

4.2. Timing of Publication

4.3. Subjects of Research

4.4. Research Content

5. Discussion

5.1. Spatial Theory Dimension

5.2. Spatial Method Dimension

5.3. Spatial Practice Dimension

6. Limitations of the Study and Suggestions for Future Research

6.1. Limitations of the Study

6.2. Suggestions for Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiao, X.M. The Value of Libraries as Public Cultural Spaces. Libr. Forum 2011, 31, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.Y. The theoretical basis of library space innovation and service practice response. Library 2021, 4, 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.Z. Introduction to Librarianship; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- RLUK Space: Hybrid and Blended Working Approaches and the Role of Space in Libraries. Available online: https://www.rluk.ac.uk/rluk-space-hybrid-blended (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Han, J.R. Research on GE Utilization Strategies Based on the Cultivation of Geospatial Literacy of Secondary School Students; Northeast Normal University: Changchun, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, C.M. The cultivation of spatial concepts in primary school mathematics from the perspective of core literacy: Reflections on the teaching of “figure and geometry” in primary school. J. Fujian Educ. Coll. 2020, 21, 90–91. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.D. A Study of Core Literacies for Student Development in the 21st Century; Beijing Normal University Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarz, S.W.; Kemp, K. Understanding and nurturing spatial literacy. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 21, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, M.F.; Janelle, D.G. Toward critical spatial thinking in the social sciences and humanities. Geojournal 2010, 75, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. Analysis of the elements of geographic spatial literacy based on core literacy. Teach. Learn. Exam. 2017, 21, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.H. A Single-Subject Study on the Development of Spatial Literacy among Geography Teacher-Training Students; Shanghai Normal University: Shanghai, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- He, L. Exploring the Formation Mechanism and Cultivation Ways of Geospatial Literacy among High School Students; Sichuan Normal University: Chengdu, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas, C.M. Evaluación post ocupacional en bibliotecas: Una revisión sistemática. Cienc. De La Inf. 2017, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Methods of systematic reviews and meta-analysis preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Yan, Z. Trajectory of Teacher Well-Being Research between 1973 and 2021: Review Evidence from 49 Years in Asia. Public Health 2022, 19, 12342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrop, D.; Turpin, B. A Study Exploring Learners’ Informal Learning Space Behaviors, Attitudes, and Preferences. New Rev. Acad. Librariansh. 2013, 19, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, M.E.; Watstein, S.B. Academic library spaces: Advancing student success and helping students thrive academic library spaces: Advancing student success and helping students thrive. Portal: Libr. Acad. 2017, 17, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelli, A.; Cunningham, S.J. Ethnography in Student-Owned Spaces: Using Whiteboards to Explore Learning Communities and Student Success. New Rev. Acad. Librariansh. 2019, 25, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleha, J.C.; Sims, I.; Spruill, O.; Bowen, A.; Russell, T.; Exner, N. Library Space Redesign and Student Computing. Public Serv. Q. 2017, 13, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsden, M.; Carey, C. Spaces for learning? Student Diary Mapping at Edge Hill University; Edge Hill University: Ormskirk, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mkyc, A.; Dkwc, A.; Ethl, B. Effectiveness of overnight learning commons: A comparative study. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2020, 46, 102253. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.Z.; Yang, C.; Ma, J.; Li, L. Analysis of factors influencing students’ autonomous activities based on SP survey. Intell. Inq. 2019, 6, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Q.; Allard, B.; Lo, P.; Chiu, D.; See-To, E.; Bao, A. The role of the library café as a learning space: A comparative analysis of three universities. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 2017, 51, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.B. Exploration of library service reengineering based on space production theory. Libr. Constr. 2014, 12, 5–7, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.L. The inspiration of Levi’s “spatial production” theory for library transformation and development. Libr. Constr. 2021, 1, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Griffis, M. Living History: The Carnegie Library as Place in Ontario. Can. J. Inf. Libr. Sci. 2010, 34, 185–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ilako, C. The Influence of Spatial Attributes on Users’ Information Behaviour in Academic Libraries: A case study; University of Borås: Borås, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J. A Comparative Study of Public Libraries in Edinburgh and Copenhagen and Their Potential for Social Capital Creation. Libri 2014, 64, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vårheim, A. Public libraries: Places creating social capital? Libr. Hi. Tech. 2009, 27, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.A. How do public libraries create social capital? An analysis of interactions between library staff and patrons. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2012, 34, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Study on Space Optimization Design of College Library in Post-Digital Map Era; Shenyang University of Architecture: Shenyang, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, A.M. Learning bodies: Sensory experience in the information commons. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2019, 41, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, Y.; Ro, J.Y.; Jeong, D.K. A study on users’ perception of the role of library in the sharing economic era in Korea. Libr. Hi Tech 2019, 38, 654–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Q. Library space layout design based on spatial experience theory. Inn. Mong. Sci. Econ. 2018, 18, 130–131. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, A.J. Principles and Strategies for Creating Cultural Space for Animation in Libraries. Libr. Inf. 2017, 4, 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Elmborg, J. Libraries as the Spaces Between Us Recognizing and Valuing the Third Space. Ref. User Serv. Q. 2020, 50, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, H.D.; Kou, Y. Study on the construction of public library space in the context of cultural scene theory. Libr. Stud. 2021, 2, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fennewald, J. The Tombros and McWhirter Knowledge Commons at Penn State. Pa. Libr. Res. Pract. 2015, 3, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.L. Research on the Design of Community Space Environment in University Libraries; Dalian University of Technology: Dalian, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.L. Research on the Design Strategy of Interaction Space of University Library based on the Evaluation of Usage Conditions; Hefei University of Technology: Hefei, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, F. Reader-centered design of interaction space in libraries. Contemp. Libr. 2011, 4, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. Space design concept based on library space attribute hierarchy theory. Libr. World 2014, 5, 1–3, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Christoffersen, D.L.; Farnsworth, C.B.; Bingham, E.D.; Smith, J.P. Considerations for creating library learning spaces within a hierarchy of learning space attributes. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2021, 47, 102458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.B. From production in space to production of space--New trends in the transformation of library services. Libr. Forum 2015, 35, 27–31, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, F.L.; Wu, Y.W. A study on readers’ behavior of learning shared space in university libraries: A case study of four universities. Libr. Stud. 2020, 23, 31, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, S.H.; Kim, T.W. What Matters for Students’ Use of Physical Library Space. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2015, 41, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.F.; Guo, J.; Yang, X.M. An empirical study on factors influencing users’ willingness to use makerspace in public libraries. Libr. Intell. Work 2018, 62, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.Q.; Liu, Q.; Ma, L.H.; Deng, J.; Qiao, X.F. A model for evaluating public library makerspaces. Libr. Constr. 2020, S1, 192–195. [Google Scholar]

- Mamolu, A.; Gürel, M. “Good Fences Make Good Neighbors”: Territorial Dividers Increase User Satisfaction and Efficiency in Library Study Spaces. J. Acad. Libr. 2016, 42, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Lux, V.; Snyder, R.J.; Boff, C. Why Users Come to the Library: A Case Study of Library and Non-Library Units. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2016, 42, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, F. Using and Experiencing the Academic Library: A Multisite Observational Study of Space and Place. Coll. Res. Libr. 2015, 6, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Identification and Analysis of Resistance and Constraints to the Development of Creative Space in College Libraries—An Analysis of Rooting Theory Based on Nvivo. New Century Libr. 2020, 10, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.R. An empirical study on the evaluation of learning commons in higher education libraries. Libr. Stud. 2020, 8, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, B.; Maria, H.; Agnes, M. How Public Libraries are Keeping Pace with the Times: Core Services of Libraries in Informational World Cities. Libri 2018, 68, 181–203. [Google Scholar]

- Burhanna, K.J.; Burhanna, K.J.; Seeholzer, J.; Seeholzer, J.; Salem, J.; Salem, J. No Natives Here: A Focus Group Study of student perceptions of web 2.0 and the academic library. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2009, 35, 523–4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rempel, H.G.; Hussong-Christian, U.; Mellinger, M. Graduate Student Space and Service Needs: A Recommendation for a Cross-campus Solution. J. Acad. Libr. 2011, 37, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.M. Space Preference at James White Library: What Students Really Want. J. Acad. Libr. 2016, 42, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjrneborn, L. Serendipity dimensions and users’ information behavior in the physical library interface. Inf. Res. 2008, 13, 370. Available online: http://www.informationr.net/ir/313-374/paper370.html (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Marino, M.; Lapintie, K. Libraries as transitory workspaces and spatial incubators. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2015, 37, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, S.E. Library Space Assessment: User Learning Behaviors in the Library. J. Acad. Libr. 2014, 40, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, K.M.; Schaller, M.A.; Hunley, S.A. Measuring Library Space Use and Preferences: Charting a Path Toward Increased Engagement. Portal Libr. Acad. 2018, 8, 407–422. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez, G. Beyond gate counts: Seating studies and observations to assess library space usage. New Libr. World 2016, 117, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Gang, J.Y.; Oh, H.J. Spatial usage analysis based on user activity big data logs in library. Libr. Hi Tech 2019, 38, 678–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullikson, S.; Meyer, K. Collecting space use data to improve the UX of library space. J. Libr. User Exp. 2016, 1, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Khoo, M.J.; Rozaklis, L.; Hall, C.; Kusunoki, D. “A Really Nice Spot”: Evaluating Place, Space, and Technology in Academic Libraries. Coll. Res. Libr. 2016, 77, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Given, L.M.; Archibald, H. Visual traffic sweeps (VTS): A research method for mapping user activities in the library space. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2015, 37, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, S.L.; Steinberg, S.J. GIS Research Methods; Esri Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.; Huang, S.T. Study on the identification and evaluation of service quality of library maker space. Library 2020, 8, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. An empirical study on the improvement path of university library service innovation based on creative space. J. Acad. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2020, 4, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, N.C.; Chen, M. Study on the influencing factors of knowledge sharing in information sharing space of domestic university libraries. Mod. Intell. 2011, 31, 3–7, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, C. The perfect combination of information sharing space and E-Literacy education: Insights from the analysis report of IC in 36 American universities. Intell. Sci. 2009, 27, 1347–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, F.F.; Guo, J.; Yang, X.M. An empirical study on the willingness to use library makerspace based on TAM. Libr. Stud. 2018, 1, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, P.; Yang, X.N. An empirical study on users’ willingness to use information sharing space: An example from the library of Binhai Campus of Tianjin Foreign Studies University. Library 2016, 6, 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, E.M.W.; Serenko, A.; Chu, S. An exploratory study of the relationship between the use of the Learning Commons and students’ perceived learning outcomes. J. Acad. Librariansh 2019, 45, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.A. The Role of Information in Governing the Commons: Experimental Results. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beavers, K.; Cady, J.E.; Jiang, A.; Mccoy, L. Establishing a maker culture beyond the makerspace. Libr. Hi. Tech. 2019, 37, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.Z. Research on the Problems and Countermeasures of Physical Space Reengineering in University Libraries in China; Liaoning Normal University: Dalian, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.H.; Xu, Q. A comparative study of domestic and international IC construction. Libr. Stud. 2008, 8, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.G.; Ma, G.D. Learning Commons: A seamless learning environment for libraries to create universities. Mod. Intell. 2009, 29, 201–204, 207. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.Y. Analysis of the idea of constructing learning sharing space (LC) in university libraries in China. Library 2011, 4, 108–110. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Tan, F.L.; Liu, Y.Y. A study on the path of building creative spaces in university libraries. Library 2021, 7, 77–81, 90. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.Z.; Xiang, X.; Zhang, L.M. Research on the service model of library data sharing space for the construction of think tanks. Intell. Sci. 2020, 38, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T. Construction of Library Telepresence Information Sharing Space in MOOC Environment. Libr. Work Res. 2017, 6, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M. A study on the practice of public library makerspace service based on 3D printing—Shanghai Library as an example. Publ. Wide Angle 2020, 1, 61–63. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Z.M. A Brief Review of 3D Printing Services at Dalhousie University Library Makerspace. Libr. Constr. 2015, 10, 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.Z. A new space for both virtual and real: Reflections on the next step of libraries in the post-epidemic era. Libr. Constr. 2021, 4, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.P.; Chen, Y.H.; Chi, X.B. A theoretical model and empirical analysis of university library readers’ spatial cognition. Libr. Hi Tech 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J. Research and reflection on the new position of user experience librarians. Chin. J. Libr. Sci. 2022, 48, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Spatial Literacy Components | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Han, 2009 [5] | ① Geospatial concept | ② Geospatial representation tools | ③ Geospatial reasoning |

| Lin, 2017 [10] | ① Geospatial perspective | ② Geospatial view | ③ Geospatial capabilities |

| Shen, 2020 [11] | ① Spatial knowledge literacy | ② Spatial perspective literacy | ③ Spatial ability literacy |

| He, 2020 [12] | ① Spatial cognition (including geographical location, spatial distribution, spatial shape, etc.) | ② Spatial thinking (including spatial connection, spatial imagination, spatial analysis, etc.) | ③ Spatial ability (including spatial reasoning, spatial use, spatial perspective, etc.) |

| The US Department of Labor’s Geospatial Competency Model (GCM) | ① Knowledge of geography subjects | ② Use of GIS, mapping, field research, etc. | ③ Performing spatial statistics, etc. |

|  |  | |

| Spatial Theory | Spatial Method | Spatial Practice | |

| Dimensionality | Research Content (Number of Papers) |

|---|---|

| Spatial theory | Learning theory, architectural theory and placemaking theory (15), space production theory (9), community space theory (3), social capital theory (6), experiential space theory (8), interaction space theory (3), the hierarchy of spatial attributes theory (2) |

| Spatial method | Survey method (55), Interview method (33), Observation method (17), Geographic Information System (GIS) technology (4) |

| Spatial practice | Information Sharing Space (288), Learning Sharing Space (240), Creative Space (364) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yang, X.; Yu, W. Are Librarians Ready for Space Transformation? A Systematic Review of Spatial Literacy for Librarians. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043244

Jiang Y, Chen Y, Wu Y, Yang X, Yu W. Are Librarians Ready for Space Transformation? A Systematic Review of Spatial Literacy for Librarians. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043244

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Yiping, Yanhua Chen, Yanqi Wu, Xianlin Yang, and Wenyan Yu. 2023. "Are Librarians Ready for Space Transformation? A Systematic Review of Spatial Literacy for Librarians" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043244

APA StyleJiang, Y., Chen, Y., Wu, Y., Yang, X., & Yu, W. (2023). Are Librarians Ready for Space Transformation? A Systematic Review of Spatial Literacy for Librarians. Sustainability, 15(4), 3244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043244