The Future Is Hybrid: How Organisations Are Designing and Supporting Sustainable Hybrid Work Models in Post-Pandemic Australia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Key Terms and Definitions

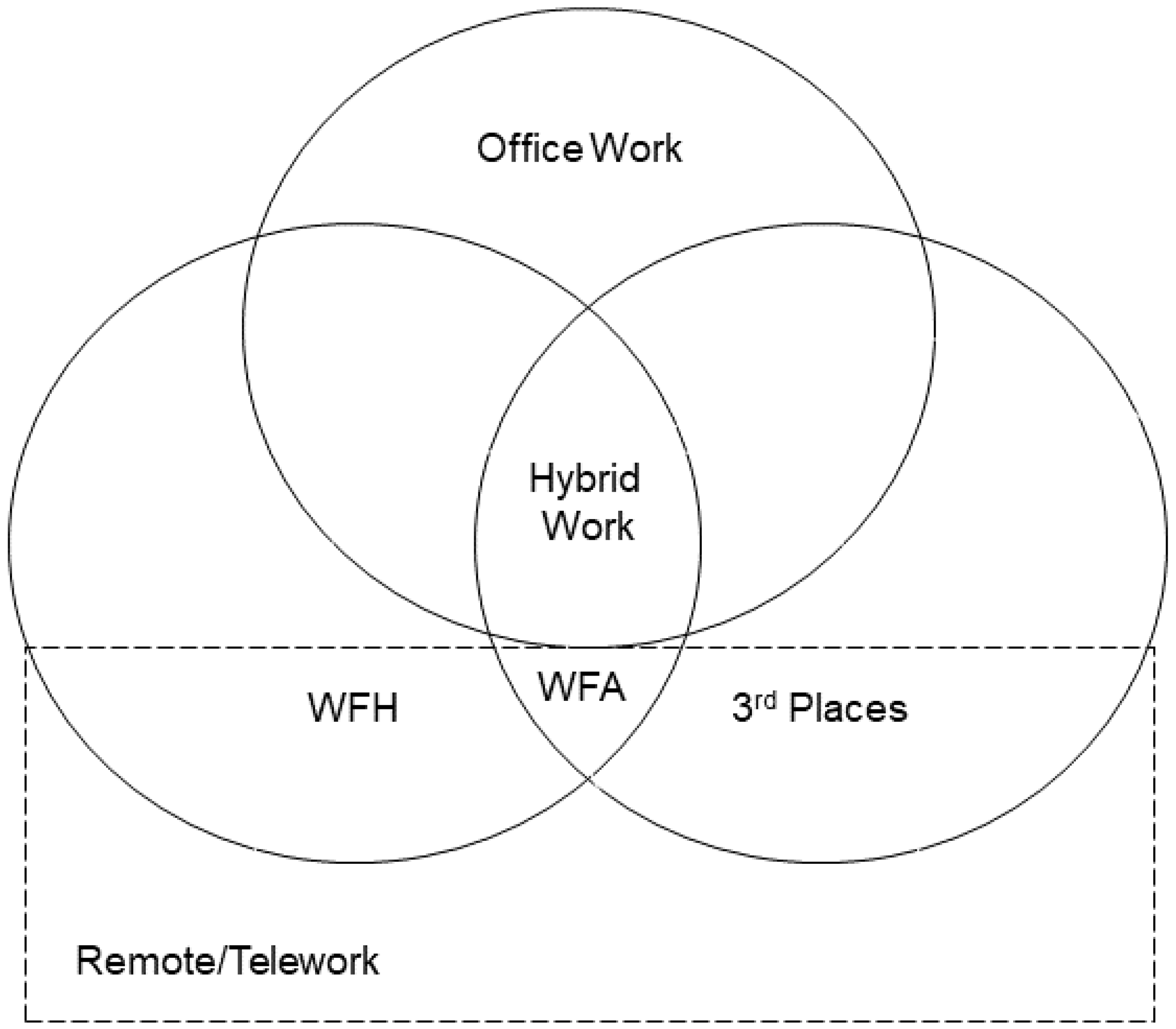

2.1.1. Hybrid Work

2.1.2. Telecommuting and Telework

2.1.3. Third Places

2.1.4. Working from Home

2.1.5. Remote Work

2.2. Conservation of Resources Theory

- (1)

- The primacy of resource loss. The first principle of COR theory is that resource loss is disproportionately more salient than resource gain.

- (2)

- Resource investment. The second principle of COR theory is that people must invest resources in order to protect against resource loss, recover from losses, and gain resources [43].

2.3. Aim of This Research

- RQ1

- What post-pandemic hybrid work models are now emerging?

- RQ2

- What are the key managerial considerations for successfully leveraging hybrid work arrangements?

- RQ3

- What role does technology play in facilitating and supporting these emerging hybrid work models?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Context

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

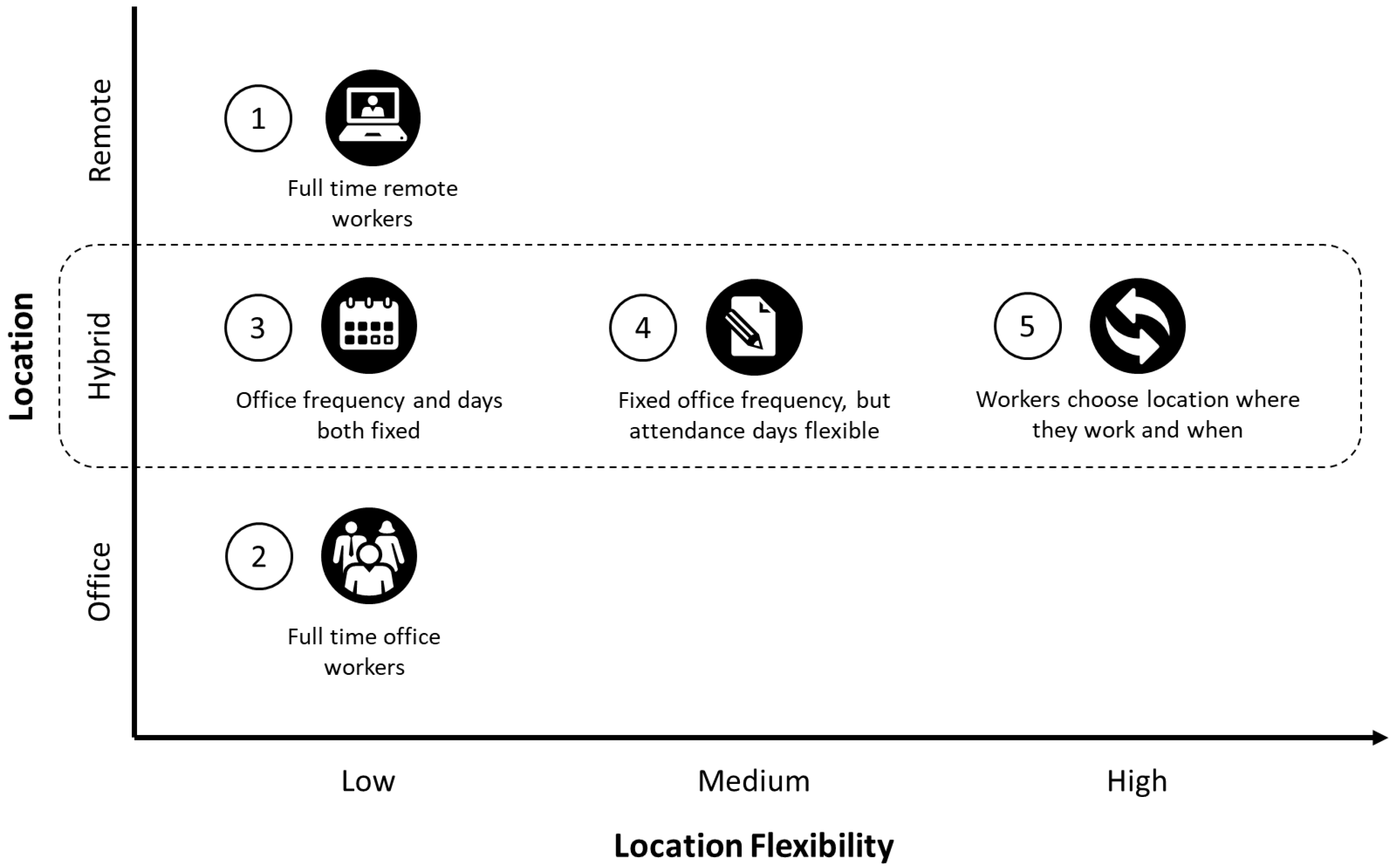

5.1. Emerging Work Arrangements

- 1.

- Full-time office workers

“I started my life as a manager thinking people can work from anywhere at any time, and be really flexible, and I very quickly stopped that because I found that our teams were drifting apart… going through COVID has affirmed my view that people have to work together… fireside chats that you have around the water cooler or having a coffee means something to people”.(A1)

- 2.

- Full-time remote workers

“So, our approach now is that no more than 20 per cent of the workforce will return to the office and we are actively recruiting people who will never be in the office”.(K1)

When asked about WFH during COVID—“I think what they’re seeing, what leaders are seeing, is that it’s really not impacting engagement, it’s not really impacting productivity and so if anything, it’s kind of helping engagement, people are more satisfied. So really I think this way of working is really going to be part of our ongoing employee value proposition as well”.(Q2)

- 3.

- Office frequency and days both fixed

“You must be in the office two days a week. Wouldn’t want everyone in at the same time. And if you’re customer service facing, you know that might be maybe more frequent. We would aim to try and have maybe the office closed Friday and Monday and have it open Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday… or whatever works best for the business, so that we get a reasonable population to get that social connectivity back”.(H1)

“Come in on a Monday and a Thursday”(M1)

- 4.

- Fixed office frequency, but attendance days flexible

“Two days of your choice, it would seem at this stage, is the way that’s going to be interpreted”.(I1)

- 5.

- Full flex—workers choose the location where they work and when

“Rather than, ‘you must be in the office a minimum of two or three days a week’, which never was the mandate or the case here, the focus is going to continue to be on, come together purposefully and meaningfully with your team to interact and collaborate face to face with your team”.(N1)

“(I think) it would be nice for people to be there one to two days but there’s nothing mandated”.(C2)

“The system in place is for, like, 5 days per fortnight and everybody in on one set date. We’re suggested that they have one common day per fortnight where everybody is on site from their team, and they can actually use that one day for workshops and meetings”.(L1)

“…the discontent created between the right and the privilege of working from home and having to come to work, that’s a very sensitive topic in the organisation at the moment”.(A1)

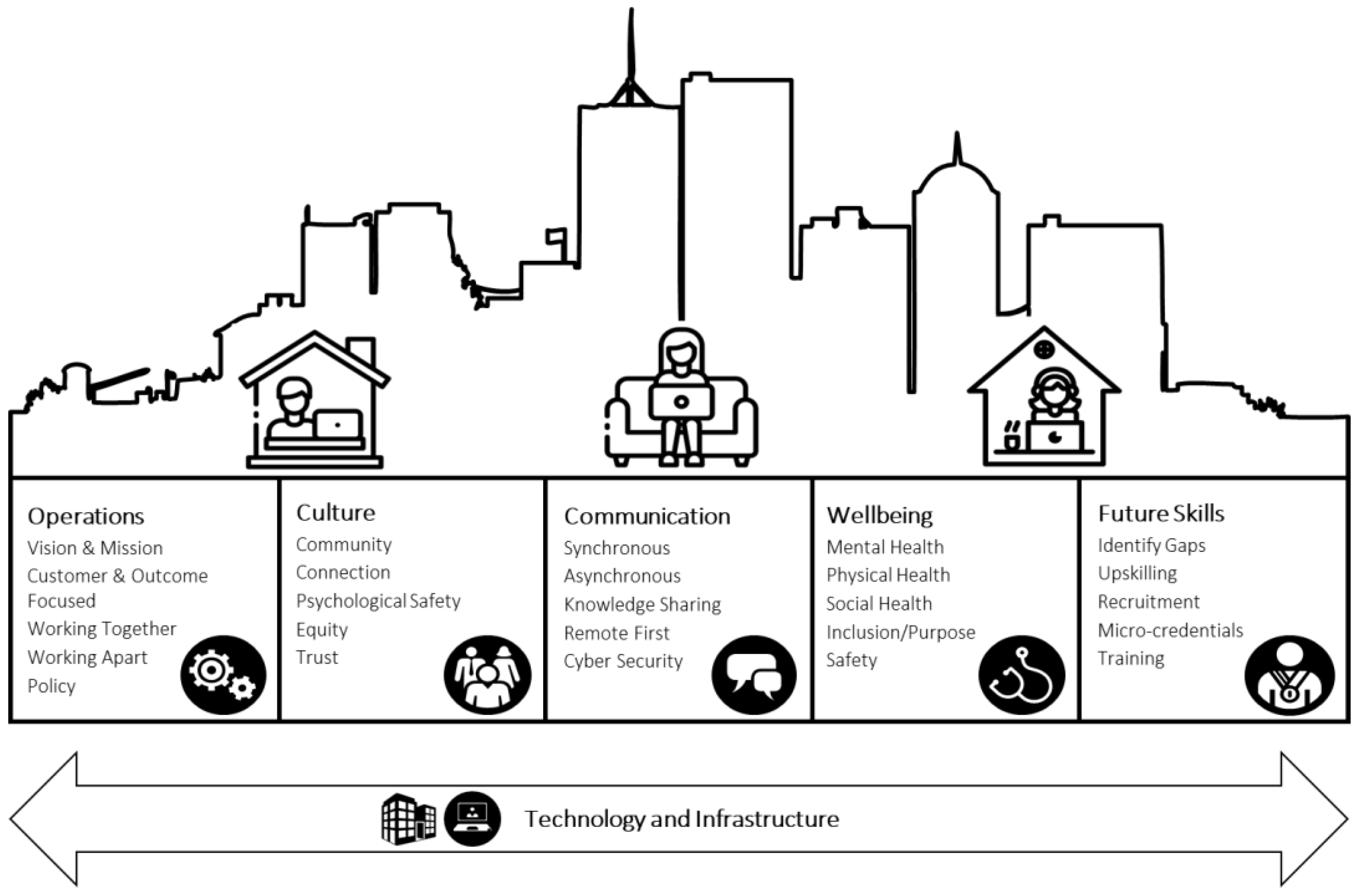

5.2. Five Pillars of Successful Hybrid Work

- Operations

“I know there are some offices that have gone with the two days at home, three days, whatever it might be, we’ve also shied away from that. Our key thing is if you’re going in, you’re going in for a reason… the idea is that the office is a place of purpose, so if you’re going in, you’re going for a reason, you’re not going in because it’s a Monday”.(Q2)

“I think prior to COVID working flexibly meant something very different and not because we said you can’t do certain things, but because people never really thought about it”.(J1)

“There might have been some ad hoc work from home if someone had a plumber coming that day, and they could log in remotely, but there was nothing formalized. In fact, it was probably actively discouraged”.(L1)

- 2.

- Culture

“We want to build an inclusive working environment and culture and that sense of belonging. It’s critical. It’s crucial to inclusion… I think that’s one for us to be really mindful of, and to work towards, in this new style of working”.(N1)

“Our culture has changed, and I wouldn’t say that it’s bad, but I wouldn’t say that we actually have our finger on what it is right now and we need to understand how do we continue to have that collaboration and that connectivity with our people in an environment that we’re now operating in and will continue to operate in for a very long time”.(L1)

- 3.

- Communication

“We switched over to being a full Microsoft Office shop in order to have Teams and we use a number of the functions that come with that Microsoft Office. So, there’s planner boards to plan our work. Obviously, Teams to facilitate the work and some other things will use outside of that product suite of things like jam boards and Mural boards for collaboration and working together… if you’d spoken to me in February 2020, I would have said to you, we don’t know what these tools are”.(L1)

“We use it (Slack) for everything, and I think one thing actually that has changed is I don’t send as many emails anymore. I have slack groups and I send it in Slack and it makes the conversation between people much easier”.(J1)

“(for meetings) if one person’s on a Zoom call, everyone should be on a Zoom call”.(Q2)

“None of us had teams up until about three weeks until into the pandemic, we were all operating off email for the most part”.(I1)

“We will have no desk phones. Everyone’s on mobile phones. We are introducing a new voice over IP system via Teams. We have lots of cyber security rules so we need to cross a few hurdles before we can implement that”.(C1)

“I think one of the things would be, from a security perspective, can we do BYO devices, what does that look like and that sort of thing. But again, that’s being explored at the moment”.(Q2)

- 4.

- Wellbeing

“I worked to establish a rhythm in weekly manager employee meetings where if you were discussing nothing else, you were at least discussing wellbeing. So, I established this rhythm that every manager was asking their employee about wellbeing”.(N1)

“We’ve done lots of work around providing mental health support, we’ve created our wellbeing ambassador team who are actually employees that are trained. They do mental health first aid training, and they are a point of contact for people who want to reach out to them, in addition to our employee assistance program”.(L1)

“We did the duty of care for working from home based on case law. Fatigue management, that sort of thing… How do I cope? How do I change? How do I adopt? How do I thrive?”(H1)

“We have ‘Wellbeing Wednesdays’ every Wednesday… lunchtime sessions with psychologists and mindfulness coaches… (and) from July through to September, and now from October through to December, we have given everybody a day off a month to just reset so they don’t have to access their annual leave. So that’s six days in six months, one day a month”.(N1)

“One is a virtual home/office audit and there’s a safety checklist that both the manager and the employee have to sign. It’s not just a post and pray, tick off. It’s a virtual audit”.(C1)

“We already had some work that had been done around ergonomic setups for home, but that actually got formalized and made more broad, so we had a policy for that in a process and we’ve got checkpoints around. That’s digital photos, risk assessments etc., that employers need to do”.(L1)

- 5.

- Future Skills

“I’ve got a psychologist coming in working with our managers on a bit of a workshop. How are you there for your people? What sorts of challenges are they experiencing? How can you support them? How can you take care of yourself?”(N1)

“A lot of training has been done. Both formal agile-based training and coaching from agile coaches. With that group… we also decided that it would be really important to do emotional intelligence”.(L1)

“It gives us a lot of opportunity to recruit from a different pool of people if we’re going work from home because we can—for example, we never would have recruited people from Western Australia (-3hrs from Australian Eastern Daylight Time) but now we’re actively pursuing that because they can cover the late shifts and not have to pay penalty rates because it’s not late for them”.(K1)

5.3. ICT Supports for Hybrid Work

“So, we went from having a small section of people that were working remotely to then everyone receiving VPN access virtually overnight and up to 4000 employees went online virtually. At that time, we also introduced our working from home package, which was to provide all the resources needed, hardware, software, furniture and the like, so people could have that home office setup at the expense of the organisation”.(M1)

5.3.1. Operations

5.3.2. Culture

5.3.3. Communication

5.3.4. Wellbeing

5.4. Theoretical Contribution

5.5. Hybrid Work through a COR Lens

5.6. Key Managerial Implications

So, the folks who do two days they don’t get the promotions. The ones that do three do and then all of a sudden everyone look for [five days]… and then we’ll be back where we started. There’s a very good chance of that happening.(I1)

But the coordination of trying to organise things with a group of people where you may only have half of them in the office at any one time, they found logistically a little bit challenging, and would prefer that we didn’t actually have people doing five days a fortnight out of the office.(L2)

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ACAS. Working from Home and Hybrid Working; Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chafi, M.B.; Hultberg, A.; Yams, N.B. Post-Pandemic Office Work: Perceived Challenges and Opportunities for a Sustainable Work Environment. Sustainability 2021, 14, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uru, F.O.; Gozukara, E.; Tezcan, L. The Moderating Roles of Remote, Hybrid, and Onsite Working on the Relationship between Work Engagement and Organizational Identification during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigert, B.; Agrawal, S. Returning to the Office: The Current, Preferred and Future State of Remote Work. Washington DC. 2022. Available online: https://www.gallup.com/workplace/397751/returning-office-current-preferred-future-state-remote-work.aspx (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Future Forum. Summer 2022 Future Forum Pulse; Future Forum: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, J.; Bardoel, A. Flexibility Makes Us Happier, with 3 Clear Trends Emerging in Post-Pandemic Hybrid Work, The Conversation. 2022. Available online: https://theconversation.com/flexibility-makes-us-happier-with-3-clear-trends-emerging-in-post-pandemic-hybrid-work-180310 (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Pickert, R. Hybrid Work Reduced Attrition Rate by a Third, Study Shows. 2022. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-07-25/hybrid-work-reduced-attrition-rate-by-a-third-new-study-shows?sref=QnKyEnuc&leadSource=uverify%20wall (accessed on 6 October 2022).

- Drapkin, A. Apple Finally Starts Hybrid Work Pilot, A Year After Announcing it. Tech.co. 2022. Available online: https://tech.co/news/apple-hybrid-work (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Shaw, W.; Anghel, I.; Gyftopoulou, L. Even Bosses Are Giving Up on the Five-Day Office Week. The Age. 2022. Available online: https://www.theage.com.au/business/workplace/even-bosses-are-giving-up-on-the-five-day-office-week-20220209-p59uvx.html (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- UN. What are the Sustainable Development Goals? United Nations. 2023. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Moglia, M.; Hopkins, J.; Bardoel, A. Telework, Hybrid Work and the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals: Towards Policy Coherence. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.B.; Castelló-Sirvent, F.; Canós-Darós, L. Sensible Leaders and Hybrid Working: Challenges for Talent Management. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werber, C. Hybrid Work is Burning Women Out. Quartz at Work. 2022. Available online: https://qz.com/work/2160634/hybrid-work-is-burning-women-out/amp/ (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Abril, D. Yelp Shuts Some Offices Doubling Down on Remote; CEO Calls Hybrid “Hell”. The Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2022/06/22/yelp-shutters-offices/ (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Felstead, A.; Jewson, N.; Walters, S. Changing Places of Work; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pyöriä, P. Managing telework: Risks, fears and rules. Manag. Res. Rev. 2011, 34, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus, M.; Glackin, S.; Hopkins, J.L. The Working-from-Home Natural Experiment in Sydney, Australia: A Theory of Planned Behaviour Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, N.; Gallagher, S.; Hopkins, J. Reset, Restore, Reframe—Making Fair Work FlexWork. 2022. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/au/en/pages/risk/articles/making-fair-work-flexwork.html (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Productivity Commision. Working from Home. 2021. Available online: https://www.pc.gov.au/research/completed/working-from-home/working-from-home.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Halford, S. Hybrid workspace: Re-spatialisations of work, organisation and management. New Technol. Work. Employ. 2005, 20, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.L.; Elangovan, A.R.; Hu, J.; Hrabluik, C. Charting New Terrain in Work Design: A Study of Hybrid Work Characteristics. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 68, 479–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, J.L.; McKay, J. Investigating ‘anywhere working’ as a mechanism for alleviating traffic congestion in smart cities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 142, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilles, J. Telecommunications and Organizational Decentralization. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1975, 23, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmot, K.; Boyle, T.; Rickwood, P.; Sharpe, S. The Potential for Smart Work Centres in Blacktown, Liverpool and Penrith; Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology: Sydney, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mears, J. Father of telecommuting Jack Nilles says security, managing remote workers remain big hurdles. Network World. 2007. Available online: http://www.networkworld.com/article/2299251/computers/father-of-telecommuting-jack-nilles-says-security--managing-remote-workers-remain-big-hurd.html (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Oldenburg, R. Our vanishing third places. Plan. Comm. J. 1997, 25, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Goosen, Z.; Cilliers, E.J. Enhancing Social Sustainability Through the Planning of Third Places: A Theory-Based Framework. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 150, 835–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, J.; Jopp, R.; Ferraro, C. Third Places: A healthy alternative to working from home? 2023. Available online: https://work.third-place.org/report (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Bloom, N.; Liang, J.; Roberts, J.; Ying, Z.J. Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment. Q. J. Econ. 2014, 130, 165–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M.H.; Primps, S.B. Working at Home with Computers: Work and Nonwork Issues. J. Soc. Issues 1984, 40, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leščevica, M.; Kreituze, I. Prospect possibilities of remote work for involvement of Latvian Diaspora’s in economy and businesses of Latvia. Res. Rural. Development. Int. Sci. Conf. Proc. 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A. The digital nomad: Buzzword or research category? Transnatl. Soc. Rev. 2016, 6, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.Y. The digital nomad lifestyle:(remote) work/leisure balance, privilege, and constructed community. Int. J. Sociol. Leis. 2019, 2, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C. Digital Nomads Alert: Spain Readies New Visa to Attract Remote Workers. 2022. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/ceciliarodriguez/2022/09/27/digital-nomads-alert-spain-readies-new-visa-to-attract-remote-workers/?sh=71b009b76229 (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M. Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.; Huang, Y.; Chang, C.-H. Supporting interdependent telework employees: A moderated-mediation model linking daily COVID-19 task setbacks to next-day work withdrawal. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajendran, R.S.; Harrison, D.A.; Delaney-Klinger, K. Are Telecommuters Remotely Good Citizens? Unpacking Telecommuting’s Effects on Performance Via I-Deals and Job Resources. Pers. Psychol. 2015, 68, 353–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, L.L.; Maynard, M.T.; Jones Young, N.C.; Vartiainen, M.; Hakonen, M. Virtual teams research: 10 years, 10 themes, and 10 opportunities. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1313–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher, C.; Anderson, D. Doing more with less? Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Hum. Relations 2010, 63, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Qian, J.; Parker, S.K. Achieving Effective Remote Working During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Work Design Perspective. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 70, 16–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgreen, L.; Tirone, V.; Gerhart, J.; Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources theory. In The Handbook of Stress and Health: A Guide to Research and Practice; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 443–457. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Westman, M.; Hobfoll, S.E. The Commerce and Crossover of Resources: Resource Conservation in the Service of Resilience. Stress Health 2015, 31, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, C.-W.; Allen, T.D.; Zafar, N. Dissecting reasons for not telecommuting: Are nonusers a homogenous group? Psychol. Manag. J. 2013, 16, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psychogios, A.; Prouska, R. Managing People in Small and Medium Enterprises in Turbulent Contexts; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, J.; Young, Z.; Bevan, S.; Veliziotis, M.; Baruch, Y.; Beigi, M.; Bajorek, Z.; Salter, E.; Tochia, C. Working from Home under COVID-19 Lockdown: Transitions and Tensions. 2021. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f5654b537cea057c500f59e/t/60143f05a2117e3eec3c3243/1611939604505/Wal+Bulletin+1.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.-M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, H.J.; Rubin, I.S. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Galletta, A. Mastering the Semi-Structured Interview and Beyond: From Research Design to Analysis and Publication; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, C. Case Research in Operations Management Researching Operations Management; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; pp. 176–209. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, K.; Dowell, A.; Nie, J.-B. Attempting rigour and replicability in thematic analysis of qualitative research data; a case study of codebook development. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Solarino, A.M. Transparency and replicability in qualitative research: The case of interviews with elite informants. Strat. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 1291–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, J.; Brocke, J.V.; Handali, J.; Otto, M.; Schneider, J. Virtually in this together—how web-conferencing systems enabled a new virtual togetherness during the COVID-19 crisis. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 563–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burleson, S.D.; Eggler, K.D.; Major, D.A. A Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Perspective on Organizational Socialization in the New Age of Remote Work Multidisciplinary Approach to Diversity and Inclusion in the COVID-19-Era Workplace; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, C.; Olaru, D.; Lee, J.A.; Parker, S.K. The loneliness of the hybrid worker. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2022, 63, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Odom, C.L.; Franczak, J.; McAllister, C.P. Equity in the Hybrid Office. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2022, 63, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, T.W.; Payne, S.C. Overcoming telework challenges: Outcomes of successful telework strategies. Psychol. J. 2014, 17, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, D. Balancing work and family with telework? Organizational issues and challenges for women and managers. Women Manag. Rev. 2002, 17, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratton, L. How to do hybrid right. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2021, 99, 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. Goldman Sachs Wants Workers Back in Office 5 Days a Week—‘A Stampede’ of Other Companies could Follow, Experts Say. 2022. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2022/03/14/goldman-sachs-wants-workers-in-office-5-days-a-week-and-other-companies-could-follow.html (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Boyle, M. Return-to-Office Plans Unravel as Workers Rebel in Tight Job Market. Bloomberg. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-05-11/wall-street-silicon-valley-return-to-office-plans-unravel-in-hot-job-market?utm_source=twitter&utm_content=business&utm_campaign=socialflow-organic&utm_medium=social&cmpid=socialflow-twitter-business (accessed on 11 November 2022).

| ID | Industry (ANZSIC) | Org. Size | % Essential | Sector | Focus | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | A—Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing | Medium (20–199) | 80 | Private | National | 36.56 |

| B1 | B—Mining | Large (200+) | 60 | Private | International | 50.23 |

| C1 | C—Manufacturing | Large (200+) | 10 | Private | International | 54.46 |

| C2 | C—Manufacturing | Large (200+) | 25 | Private | International | 40.55 |

| H1 | H—Accommodation and Food Services | Large (200+) | 60 | Private | International | 49.54 |

| J1 | J—Information, Media and Telecoms | Medium (20–199) | 0 | Private | International | 44.58 |

| K1 | K—Financial and Insurance Services | Large (200+) | 20 | Private | National | 52.29 |

| L 1 | L—Rental Hiring and Real Estate Services | Large (200+) | 66 | Private | International | 41.51 |

| M1 | M—Professional, Scientific and Technical Services | Large (200+) | 20 | Public | National | 51.02 |

| N1 | N—Administrative and Support Services | Large (200+) | 0 | Private | International | 44.53 |

| P1 | P—Education and Training | Large (200+) | 5 | Public | International | 50.26 |

| Q1 | Q—Health Care and Social Assistance | Large (200+) | 50 | Private | Local | 33.14 |

| Q2 | Q—Health Care and Social Assistance | Large (200+) | 12.5 | Private | National | 40.45 |

| I1 | I—Transport, Postal and Warehousing | Large (200+) | 75 | Public | Local | 43.12 |

| M2 | M—Professional, Scientific and Technical Services | Small (<20) | 5 | Private | Local | 49.24 |

| Lessons | Appear in Interviews | Themes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Hybrid work requires purposeful and flexible policies around when and where work is performed, accounting for customer expectations, individual preferences and circumstances, and technological resources | “purposive” 1, 4, 6, 7, 11, 12, 14 | Operations, communication, culture, technology |

| 1a. Job differences, manage divide | 1, 2, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 | |

| 1b. Customer expectations | 5, 9, 13, 15 | |

| 1c. Individual preferences | 9, 15 | |

| 1ci. Hard to get people back to workplace | 2, 11 | |

| 1cii. Survey/consult employees on preferences | 2, 4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 | |

| 1d. Individual circumstances (e.g., children, domestic viol.) | 3, 6, 9, 13, 15 | |

| 1e. Need right technological resources | 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15 | |

| 1ei. Need to use technology wisely | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15 | |

| 1eii. Hybrid meetings don’t work | 3, 4, 5, 7, 10, 13 | |

| 1eiii. Importance of cybersecurity | 2, 6, 7 | |

| 1f. Tasks requiring personal interaction bad on Zoom, worse on phone | 1, 4, 7, 11, 12, 13, 15 | |

| 1g. Heightens importance of cross-function coordination | 2, 3, 5, 11, 13, 14, 15 | |

| 1h. Hard for new employees to build connections | 4, 5, 7, 11, 12 | |

| 2. Trust or clear measures of output are required for hybrid work | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 12, 14, 15 | Operations, culture, communication |

| 2a. Presenteeism undercuts hybrid work | 3, 6, 7, 9, 11, 14 | |

| 2b. Managers who prefer control undercut hybrid work | 7, 9, 13, 14 | |

| 3. Need clear policies/resource provision for home offices | 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 12, 13 | Operations, communication, infrastructure |

| 3a. Except for small orgs | 15 | |

| 4. Hybrid work easier for young people because tech savvy and not set in ways | 3, 6, 9, 14, 15 | Technology |

| 5. Walk the talk to make hybrid work | 14 | Culture |

| 6. Workplace for collaboration, as needed | 4, 5, 12, 14 | Infrastructure |

| 7. Work-from-home isolating | 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 9, 10, 13 | Wellbeing |

| 7a. Need to plan all-in meetings, social time/events | 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12 | |

| 7b. Need to plan 1-on-1s or teams to stay in touch w. employees | 2, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 13 | |

| 8. Mental health response important | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 | Wellbeing |

| 9. Decentralize flex to team level | 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, 12 | Operations |

| 9a. Adjusted work practices so recruiting improved | 7, 9, 10, 11, 12 | Future skills |

| 10. Losing employees during lockdown | 11, 12, 13 | Future skills |

| 11. Problem of excess space with partial return (hotdesk) | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13 | Infrastructure |

| 11a. Safety/loneliness issue of working alone or w. few in office | 7, 9 | |

| 11b. Flex not even for mothers prior | 3, 11, 13 | |

| 12. Pre-pandemic little flex, mainly for moms | 9, 12, 14, 15 | Operations, culture |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hopkins, J.; Bardoel, A. The Future Is Hybrid: How Organisations Are Designing and Supporting Sustainable Hybrid Work Models in Post-Pandemic Australia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043086

Hopkins J, Bardoel A. The Future Is Hybrid: How Organisations Are Designing and Supporting Sustainable Hybrid Work Models in Post-Pandemic Australia. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043086

Chicago/Turabian StyleHopkins, John, and Anne Bardoel. 2023. "The Future Is Hybrid: How Organisations Are Designing and Supporting Sustainable Hybrid Work Models in Post-Pandemic Australia" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043086

APA StyleHopkins, J., & Bardoel, A. (2023). The Future Is Hybrid: How Organisations Are Designing and Supporting Sustainable Hybrid Work Models in Post-Pandemic Australia. Sustainability, 15(4), 3086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043086