Abstract

Family farming is strengthening its strategic role in school nutrition, but coordinating between school feeding programs and the agricultural sector has proven to be challenging. The goal of this review was to identify the problems that school feeding programs face in acquiring food from family farms. We selected studies from Web of Science, Medline/PubMed, and Scopus and evaluated their methodological quality. Out of 338 studies identified, 37 were considered relevant. We used PRISMA to guide the review process, and we chose not to limit the year or design of the study because it was important to include the largest amount of existing evidence on the topic. We summarized the main conclusions in six categories: local food production, marketing, and logistics channels, legislation, financial costs, communication and coordination, and quality of school menus. In general, the most critical problems emerge from the most fragile point, which is family farming, particularly in the production and support of food, and are influenced by the network of actors, markets, and governments involved. The main problems stem from the lack of investment in family farming and inefficient logistics, which can negatively impact the quality of school meals. Viable solutions include strategies that promote investment in agricultural policies and the organization of family farmers.

1. Introduction

The debate surrounding the transformation of food systems—for greater efficiency, resilience, inclusion, and sustainability—has gained strength in international and national agendas and is a condition for the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [1]. Family farming can play an important role in this transformation, particularly in terms of reducing poverty, hunger, and climate change [2,3].

Although there is no universal consensus on the definition of family farming, given its enormous diversity around the world, the Global Action Plan of the United Nations Decade for Family Farming—2019–2028 [2] uses family farming to refer to all models of family-based production—agricultural, forestry, fishing, pastoral, or aquacultural—including peasants, indigenous peoples, traditional communities, fishers, mountain farmers, forest users, and herders. These farms/properties have economic, environmental, social, and cultural functions. It is estimated that globally there are around 570 million family farms, which occupy 70 to 80% of agricultural land and are responsible for producing 80% of food [4,5]. Evidence shows that family farming, when adequately supported by public policies and investments, has the ability to effectively contribute to food insecurity and poverty reduction [6], biodiversity conservation [7], local economic development [8], and food resilience in times of crisis [9]. Despite their potential benefits, smallholder farmers are most affected by food insecurity and extreme poverty [10]. It has been found that over 70% of people with food insecurity in the world live in rural areas of developing countries, in a disturbing paradox [11]. Many of these people are poorly paid agricultural workers or subsistence farmers who may struggle to meet the food needs of their families.

A shift in the way small producers are viewed has been observed in recent international, national, and regional political debates: they are now seen as central to the resolution of hunger, rather than being viewed simply as part of the problem [12]. Therefore, the issue of how small-scale farming can be crucial to social and environmental protection is of central importance for policy interventions, particularly for school feeding programs.

School feeding programs benefit about 388 million children worldwide, and governments are increasingly recognizing their multiple benefits for populations, such as social protection and food security for students [13]. When linked to family farming, programs can contribute to the development of shorter and closer production chains to schools, while the supply of local and culturally appropriate food can reduce waste and, consequently, carbon emissions [14,15]. From an economic point of view, these programs can also enhance job creation and local economic dynamization, essential factors for reducing poverty and food insecurity in the countryside [16].

However, the growth of initiatives linking family farming and school feeding does not necessarily guarantee their effective implementation in different scenarios. Most of the time, the coordination between the supply of food from family farms and the demand for food for schools can be challenging. Botkins and Roe [17] reported that the challenges that condition the participation of school districts in the Farm to School program in the United States range from high product prices to the unavailability of food throughout the school year. Similarly, some studies [18,19,20,21] from Brazil point to the mismatch between the supply of food and school demand, a situation that is directly affected by three main factors: poor logistics, poor communication, and lack of public sector support.

Therefore, our objective with this systematic review is to answer the following question: What are the problems and potential solutions that school feeding programs in different contexts face in acquiring food from family farms? To do this, we aimed to systematize and characterize the evidence produced to date so that future research can fill the identified gaps and contribute to the effective inclusion of family farming in school feeding programs.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted based on the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) recommendations. We did not register a protocol for this review because our research does not directly analyze any health-related outcomes [22].

2.1. Search Strategy

The research was carried out during the month of March 2022, and three databases were used to conduct the search: Web of Science, Medline/PubMed (via National Library of Medicine), and Scopus, due to their good coverage in collecting evidence for systematic reviews [23]. The research consisted of applying the descriptors, and the search strategies are detailed in the Supplementary Materials.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

We selected articles according to the following eligibility criteria: (i) original articles, published in English, Spanish, or Portuguese; and (ii) studies based on experiences of the participation of family farms in school feeding in different contexts. We chose not to limit the year or design of the study because it was important to include the largest amount of existing evidence on the topic. We limited our research to papers that included primary data in order to prioritize the most reliable source of information, which helps to reduce bias and increase the validity of the findings.

2.3. Studies Selection

A search strategy generated more articles than were eligible according to the eligibility criteria. Screening titles and abstracts in the initial phase allowed for filtering references and eliminating a significant number of studies that did not meet the criteria established for the review. For example, studies that focused on other issues related to school feeding, such as food and nutrition education practices, food safety practices, and estimation of food macro- and micronutrients, were not included if they were not related to family farming. Titles and abstracts were selected based on the descriptors used in the search strategy. We used the Rayyan Qatar Computing Research Institute (QCRI) and Mendeley reference managers to organize the studies based on the merging of the databases and the exclusion of duplicates. Initially, the titles and abstracts were subjected to the first screening by two independent authors (VMC and SMG), in which studies that did not meet the eligibility criteria were excluded. In case of disagreement or uncertainties about inclusion, a third author was consulted (MCMJ). The full texts were retrieved and reviewed by VMC to confirm the eligibility of the study, and in case of doubt, the other authors were consulted. A supplementary manual search was also carried out to identify additional studies based on the references of the selected articles; however, no studies were added.

2.4. Data Extraction

Two authors (VMC and SMG) extracted the data and we compiled the relevant information into a spreadsheet for this study. We collected the following information: (i) article data (authors, publication year, journal of publication), (ii) location of the study (city, state, region, and/or country), (iii) overall objective, (iv) type of study, (v) participants, (vi) data collection technique, (vii) variables or categories of analysis, (viii) main results, and (ix) study quality.

We methodologically evaluated the quality of the studies using the following protocols: Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) [24], Joanna Briggs Institute Prevalence Checklist (JBI) [25], Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [26], and Analytical Quality Control (AQC) [27]. For the analysis of qualitative studies, we used COREQ, which is a checklist with 32 criteria for evaluation. In the case of observational studies, we considered two protocols, one for cross-sectional studies (JBI) and one for cohort and case-control studies (NOS). Both instruments had nine evaluative items. Finally, we used AQC, a protocol with 21 criteria to analyze the only experimental study in the sample.

After assessing all items, the studies received a score for each criterion met. The quality of the studies was categorized using the criteria of Jacob, Araújo, and Albuquerque [28]. These categories were as follows: strong—when the quality was >80% of the criteria of the referenced checklist; moderate—when it was between 50–80%; and, finally, weak—when it met <50% of the required criteria. In cases of studies with mixed methods and using more than one protocol, we calculated the arithmetic mean and applied it again to the quality categories.

2.5. Summary of Results

We present the results descriptively and by absolute frequency. We produced summaries of each of the articles and systematized the main conclusions. The qualitative data was extracted using the thematic analysis technique. These data were segmented, categorized, summarized, and reconstructed to capture the main information that could answer our research question within our data set. In a spreadsheet, the data was organized and analyzed through the following steps: (1) from the main conclusions of the selected studies, we grouped the useful evidence into categories of equal weight; (2) from the evidence, we developed the first level of conclusions (more restricted), highlighting what was common among the studies; and (3) finally, we categorized the restricted conclusions into general conclusions.

3. Results

3.1. Studies Included

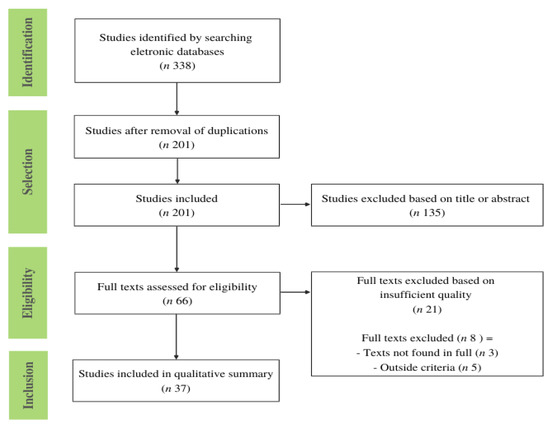

The database search resulted in 338 studies (130 in Web of Science, 44 in Medline/PubMed, and 164 in Scopus). After excluding 137 duplicates, 201 articles were considered eligible for the next screening stage. Based on the titles and abstracts, 66 articles were selected for a full reading. Subsequently, we excluded 29 studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria (n = 8) and that were classified as weak in the quality analysis criteria (n = 21). Thus, theoretical and review studies, policy briefs, and articles unavailable in full were removed at this stage. In the end, a total of 37 articles were considered eligible and relevant for this systematic review. The process of selecting the articles is described in the flowchart in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the studies selection process.

3.2. Studies’ Characteristics

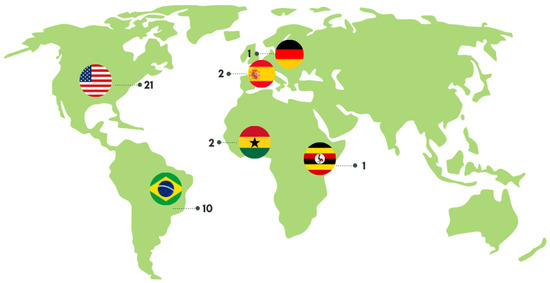

Table 1 provides an overview of the main characteristics of the 37 studies in this review. Of the included studies, 27 were published in the last 10 years, 17 of which between 2018 and 2022. The first study in this review was published in 2006 [29], and most of the subsequent publications occurred from 2013 on. Most of the included studies (83.8%) focused on experiences located in the United States and Brazil (see Figure 2). Both countries, as well as the Republic of Ghana, have government programs to include local foods in schools, such as the Farm to School Program (FTS), the National School Feeding Program (PNAE), and the Ghana School Feeding Program. We also found different experiences in European (Spain and Germany) and African (Ghana and Uganda) countries, albeit in small numbers. Some of them refer to the role of agricultural policies or non-governmental organizations in promoting the purchase of local foods for schools. The most commonly adopted study method was observational cross-sectional (54.1%), followed by qualitative studies (27%), cohort studies (10.8%), and mixed methods (8.1%).

Table 1.

Characterization of studies on family farming in school feeding.

Figure 2.

Number of studies distributed by countries.

3.3. Quality Analysis

We selected studies with strong (n = 20) and moderate (n = 17) quality. Studies classified as low quality were generally qualitative in methodology, followed by cross-sectional and cohort studies. For qualitative studies, the omission of relevant information about the methodological design and data analysis weighed on the decision, as well as the consistency between the presented data and conclusions. In both cross-sectional and cohort studies, the main weaknesses were the limitations of small sample size and lack of representativeness, as well as issues with sampling criteria and variable measurement.

3.4. Difficulties in Acquisition of Food from Family Farming for School Feeding

This study sought to identify the challenges faced by school feeding programs in the acquisition of food from family farms. Based on the main findings of this review, we present six categories that directly and indirectly influence the acquisition of family-based foods for schools, grouped into three dimensions corresponding to food production, acquisition support elements, and consumption (Figure 3). In relation to food production, we highlighted the impacts that affect the supply of food to schools, from productive capacity to commercialization logistics and market competition between small, medium, and large producers. In the second dimension, we listed studies that report difficulties related to support elements—those that guide and regulate the dynamics of food acquisitions in school feeding programs—such as the current legislation (local, regional, or national), costs and expenses generated by foods, and communication/articulation among the stakeholders involved. Finally, we highlighted the barriers involving the consumption of food in schools, considering aspects related to health, culture, and the environment.

Figure 3.

Summary of the main conclusions of studies that analyzed the participation of family farming in school feeding. Numbers corresponding to Table 1 (see column 1 “Study no”).

3.4.1. Production

We found that low production capacity, irregular supply, and unpredictability in food supply [29,50,53,58] are barriers reinforced by the social, economic, environmental, and political characteristics of the locations [30,38,49,56,59]. In general, municipalities or school districts that are less likely to adopt local food purchases are poorer and have a lower Human Development Index (HDI) [18,37,48]. In addition to this, the size of the municipality/school district and the distance between production and schools are factors that influence access to these foods. While large municipalities are more attractive to farmers due to the high demand generated, some studies have concluded that the larger the municipality, the greater the logistical difficulties in supplying, transporting, and storing food [18,37]. The same situation was observed in school districts. Smaller districts had fewer obstacles (for example, delivery costs, supplier payments, and food volume) compared with medium and large districts [56]. With regard to the distance between production and schools, some studies showed the influence of distance on production costs, delivery dynamics, diversity, and quality of the foods offered [49,55,59]. Soares et al. [59] reported in a study conducted in southern Brazil that proximity between production and school reduces transportation time and favors the consumption of fresher and healthier foods.

Findings regarding the commercialization of food for schools demonstrate that logistical challenges—including irregular supply and low production capacity—in models of local food acquisition directly from the producer increasingly reinforce the participation of national food chains and intermediaries in this market niche [40,43,49,50,53,61]. Some studies justify that the benefits brought by these distribution and commercialization channels include the ability to provide food throughout the school year, in sufficient volume, at competitive prices, and to the required sanitary standards [21,29,40,45,51,54,56,62]. On the other hand, while the efficiency of these channels in regularly supplying food is recognized, the social, cultural, economic, and environmental impacts of these foods traveling long distances through complex supply chains are also questioned [43].

3.4.2. Support

Our review suggests that contradiction in the regulatory devices of the programs tends to produce new conflicts between those who should benefit. Studies have reported that policies/programs with contradictory and inconsistent laws create room for broad interpretations by their implementers and therefore run the risk of not being adequately carried out [29,32,47]. Braun et al. [32] found that while implementing a policy of purchasing organic and locally sourced foods for school meals in Berlin led to an increase in the availability of organic foods in schools, the origin of these foods was not local. As a result, the new policy provided little benefit to the local farming niche, which did not see increased demand following its implementation. At the same time, the excess of regulation increases the bureaucratization of purchases and limits the power of sale of these foods [29,30,36,60]. In the case of Brazil, for example, the bureaucracy of public purchases mainly affects the sanitary standards for the acquisition of animal products [38,51], the certification of organic foods [18,36], and the process of how the foods are acquired (through administrative instruments) [30,60]. In these circumstances, most family farmers, when unable to meet the requirements necessary to participate in this market, are discouraged and conditioned to sell their products at local markets, since marketing for government programs runs into regulatory devices.

In regards to financial costs, while school agriculture programs have been widely promoted as a market opportunity for family farming, the profit generated by these acquisitions has little impact on farmers’ income [43]. In general, the profits represent a very small portion of the total agricultural income of the farmer, which is mainly composed of sales at farmer’s markets and to intermediaries [30,43]. Part of these payments is delayed and further discourages the participation of farmers [55,56]. The food costs related to school purchases have also been classified as a barrier to the maintenance of these programs [31,35,46]. It has been suggested in studies that when schools purchase local food from conventional distributors, the financial costs may be higher compared to schools purchasing directly from farmers [32,36,41,47]. In addition, instability in food prices can also dictate the dynamics of acquisitions, so when prices rise, the supply and demand opportunities for the programs decrease [17].

Our findings also highlight that some of the difficulties encountered in purchasing food for schools are related to weak communication among the network of actors [30,43,57]. In these cases, the lack of communication, coordination, and transparency are recurring issues in different scenarios that tend to distance the inclusion of farmers in these programs [30,57]. As reported in the study by Izumi et al. [43], when the number of nodes between producers and school food agents increases, the opportunity for coordination between the ends of the chain is lost, and all actors are disadvantaged.

3.4.3. Consumption

Studies show that the absence of locally grown foods negatively impacts the quality of school meals, making them less healthy and culturally inappropriate [33,42,48]. We also found that the inclusion of local foods was associated with higher consumption of fruits and vegetables and lower consumption of processed foods among students, indicating a positive relationship between locally grown foods and fruit and vegetable consumption [18,48]. From a sensory perspective, Greer et al. [42] found in their research that, in the perception of students, local products were of higher quality than non-local products (taste and freshness). Students also pointed out that the consumption of local foods is associated with caring for the environment. From a cultural standpoint, school menus based on local food preparations are associated with greater acceptance by the school community, as well as contributing to the preservation of food habits, biodiversity conservation, and sustainability [33]. In addition, the underutilization of locally available food resources and lack of knowledge about their food potential reduce opportunities for the inclusion of strategic foods in school meals, especially in economically disadvantaged areas [39].

4. Discussion

The main objective of this review was to identify difficulties faced by initiatives in school feeding programs to acquire local food from family farms. Based on our analysis, we saw that although experiences linking local food to schools have expanded worldwide in recent years, this growth is not necessarily reflected in the consolidation of these initiatives. In general, difficulties occur at all stages of acquisition, from production to consumption, and are influenced by the network of actors, markets, and governments involved. However, the studies analyzed indicate that the most critical problems emerge from the most fragile point, which is family farming, particularly in the production and support of the food.

Below, we list some lessons learned from the results of this review, and point out alternative ways to mitigate the fragilities found.

4.1. Challenges We Need to Overcome to Sustain the Supply of Local Food from Family Farming in School Meals

The inclusion of local foods in school meals has already proven its importance worldwide, but we still need to make progress in consolidating this market. Based on the six barriers identified in this review, we have found three key issues: (1) the lack of public incentives for agricultural/rural development weakens the participation of family farming in school feeding programs; (2) the logistics of the local food supply chain for schools is very sensitive to the actions of actors, markets, and governments; and finally, (3) the quality of school meals depends directly on the success of the previous steps.

First, we consider that without investment in family farming, local foods are unlikely to reach the tables of school children. Nehring et al. [63] believe that support policies for small producers are essential to ensure the success of the participation of family farmers in institutional markets and public programs. We currently observe that the food production and marketing sector is experiencing a great paradox: on the one hand, most of the investments for agricultural development, from public and private sectors, are directed towards export value chains (commodities); while on the other hand, investments for family farming are made by the farmers’ own families [64]. Overall, the studies we have gathered indicate that the main difficulty in supplying food for schools is the limited production capacity and irregular supply of food throughout the year. Our experiences have also shown that family farming lacks public policies for agrarian/rural development and financial resources to enter and remain in this school supply market. According to the report Investing in Smallholder Agriculture for Food Security [64], investments in family properties contribute to facilitating producers’ access to productive assets (land, inputs, electricity, irrigation, etc.), which allow them to increase their productivity, improve their access to and creation of different markets through strategies that combine public and private investments, and develop state policies that regulate production models and markets suitable for small landowners. Similarly, Birner and Resnick [65] argue that meeting the market demand for family agriculture, with high yields and productivity, requires public strategies to support agricultural production. The authors also argue that institutional markets, for example, are a key political intervention for agricultural development and social protection, as they synergistically stabilize prices, generate income, and ensure food security. Therefore, we believe that increasing investment in family agriculture is the first step in overcoming the limitations of the food supply for school feeding programs. Consequently, this investment is essential for generating income, employment, and means of subsistence, and can be strategic in reducing poverty and food insecurity in rural populations.

In the second place, logistics operation is the most critical step and one that is most susceptible to interference throughout the process of acquiring local foods for schools. This step integrates an extensive and complex network of actors, markets, and governments, and therefore is subject to the influence of various factors. However, most logistical problems fall on the weakest link in this chain, which is the farmer. Studies report several factors that hinder the progress of this step, such as distance, family properties being far from schools and main consumption centers, which makes it difficult to transport fresh food and increases the cost of distribution/delivery [66]; lack of infrastructure, difficulty in storing and transporting their products appropriately [67]; delay in payments, inconsistency in payment by governments weakens negotiations between farmers and school feeding programs [68]; lack of knowledge about legislation regulating programs, difficulty in understanding how to provide food for government programs or other institutions [69]; and weak communication, which hinders understanding of the process and interaction between stakeholders [20]. These problems coincide with the findings of this review. For example, in the United States, Brazil, and Ghana, countries with older and more structured school feeding programs, logistics is a gap that repeats itself in different contexts [68,70,71]. However, the capacity to invest in the family agriculture market, the willingness of governments (political will), and the degree of engagement of social actors are decisive factors in establishing efficient and well-planned logistics.

Consequently, in the third place, we understand that a lack of incentives for farmers combined with inadequate logistics can negatively impact the quality and availability of food for school feeding programs. The results of this interfere with the quantity and variety of school diets. Studies report an increase in organic foods [72], a decrease in sugar-rich foods [73], and a reduction in ultra-processed [74] foods in school menus when linked to family farming. The supply of biofortified and underutilized foods has also been used as a strategy to promote adequate and healthy nutrition in schools [75,76], especially in low- and middle-income countries. Furthermore, the consumption of locally grown food in schools has been an incentive for building more sustainable food systems [77]. In some Latin American countries, for example, pilot projects known as “Sustainable Schools” are being implemented in school meal programs to include a greater variety of foods from local small farmers [78]. Therefore, we emphasize that ensuring a good quality of school meals involves not only the availability of foo, but a set of measures that support the farmer throughout the entire production, marketing, and distribution chain.

Finally, we highlight that the barriers previously raised can become even more complex depending on the socioeconomic characteristics of each place. Our findings indicate that in low-income countries, for example, the opportunities for farmers to participate in school feeding programs are even more limited. Globally, it is estimated that between 2013 and 2020, the number of children receiving school meals grew by 9% worldwide, reaching a coverage of 388 million [13]. In general, low-income countries have lower coverage, less established programs, and rely more on external funding. On the other hand, high- and middle-income countries stand out for their institutionalized regulatory frameworks, increasing policy support that engages with school feeding, and continuous monitoring of the food and nutrition status of schoolchildren—through population-based food surveys [79,80]. Therefore, we consider that national income level is also a factor that influences the structure of practices linked to family farming in school feeding programs. However, the difficulties discussed in this review need to be contextualized according to local realities, so that future interventions meet the specific needs of each context.

4.2. Possible Pathways for Rebuilding the Link between Family Farming and School Feeding

Based on this review, we highlight six main barriers that need to be overcome for the successful engagement of family farming in school feeding programs. We emphasize that the most critical issues arise from the lack of investment in family farming and the inefficient logistics, which can, in turn, impact the quality of school meals. In Box 1, we suggest some strategies to mitigate the difficulties found.

Box 1. Strategies to facilitate the supply of food from family farming for school meals.

- Invest in support policies that improve access for family farmers to markets (institutional or otherwise) and essential public goods.

- Design laws for the local procurement of school foods with clear objectives, reducing biases for diverse interpretations.

- Increase investment in family farming and ensuring sustained political commitment to inclusive governance at the local, national, and international levels.

- Invest in public-private partnerships to offer different market opportunities.

- Create linkages between farmers and school meal services to strengthen direct and responsive communication.

- Increase the diversity of school meal menus by including local foods, to ensure better quality meals for students.

- Strengthen farmer organizations (formal or informal) and improve the logistics of the food supply chain for schools through cooperatives and associations.

- Invest in national/regional/local research to assess the state of family-origin acquisitions in school feeding programs, from a holistic perspective.

In summary, the suggested strategies recognize that small family farmers need organization, sustainable practices, and social protection. Here we list some arguments that support our proposal. First, the integration of small agricultural producers into food, input, and service supply chains is essential to keep them competitive and protect their means of livelihood. Family farming cooperatives and associations can help enhance this integration by improving the logistics of the supply chain and facilitating access to productive resources, such as machinery, equipment, and rural credit, as well as increasing marketing power [1]. A study conducted in Austrian municipalities identified that cooperatives are vital for small farmers trying to establish themselves in local food supply systems [81]. Cooperatives promoted infrastructure, logistics, and shared transportation, processing methods, as well as agricultural know-how. Experiences in Brazil and the United States have also shown that cooperated farmers have been able to expand food marketing and maintain availability throughout the year, including for school feeding [67,82].

Second, cooperatives can act in the formation of social capital. The linking of social capital within organizations positively influences the establishment of trust, transparency, communication, and commitment among its members and, therefore, can help in overcoming problems [79]. Some studies show the potential of social capital to mitigate family income and food supply shocks, especially in times of crisis [83]. It can be observed that trust and mutual knowledge among members of a social group can increase the propensity for sharing food or money for food purchases [84]. Thus, a lower propensity to hunger is observed in families with higher levels of social capital. Similarly, agricultural productivity can be influenced by social capital, which promotes the exchange of information among its members and the adoption of better agricultural practices and technologies [83]. Therefore, cooperatives and associations are considered potentially effective means of increasing the livelihoods of farmers through the reduction of information asymmetry and transaction costs.

Our third argument is that school feeding programs, which encourage the purchase of local foods, can help minimize the impacts of climate change and the depletion of natural resources. The implementation of shorter, local food supply chains can have several benefits. In addition to promoting a preference for fresh foods, this strategy can also help reduce the need for transportation, which leads to lower carbon emissions [13]. Furthermore, supporting local small farmers can increase the resilience of local food systems. However, strategies to support family farming should consider the adverse effects of climate change [85]. According to the Special Report on Climate Change and Land [86], farmers are particularly vulnerable to climate change because their livelihoods often depend on agricultural production. As extreme weather events become more frequent, producers will need subsidies that provide immediate and short-term relief in cases of agroclimatic disasters [1]. However, long-term measures are necessary to strengthen the resilience of farming families [87].

Overall, we believe that school feeding programs can be even more effective when approached from a holistic and multisectoral perspective that takes into account biological, social, cultural, economic, and environmental dimensions. These programs are typically associated with education and health agendas, where efforts are focused on combating child hunger and nutritional deficiencies and increasing school participation and learning. However, evidence shows that the potential benefits of these programs extend to at least four main sectors: health, education, social protection, environmental protection, and agriculture [88]. The effects of this “win-win” relationship cross sectoral boundaries and impact various domains. For example, from a nutritional and agricultural perspective, biofortified foods can be incorporated into school meals, bringing health benefits as new technologies are developed and local agricultural production is maintained [89]. From an economic perspective, the programs can have a good cost-benefit ratio when viewed from the perspective of their multisectoral return, which can reach up to USD 9 in benefits for every USD 1 invested, meaning that school feeding can generate returns on investment in other sectors [88]. In terms of education and social protection, school feeding also reduces school dropout, which in turn improves educational performance and reduces the risk of child labor [89]. For example, Dyngeland et al. [90] analyzed the Zero Hunger strategy in Brazil and found that investments in the National Program for Strengthening Family Agriculture (PRONAF) and the rural credit program were strategic in driving the success of social policies, especially in synergy with the SDGs. Thus, the investments in Zero Hunger were translated into advances to increase the availability of food (SDG 2), reduce poverty (SDG 1), and conserve natural vegetation (SDGs 13 and 15).

5. Conclusions

Problems in linking family farming to school feeding programs are most evident in food production, where reduced productive capacity, irregular supply, and inefficient logistics are more common. Barriers, such as current local legislation, financial costs, and lack of communication, also hinder the relationship between farmers and program-responsible parties. The lack of locally grown foods also affects diversity and, consequently, the quality of school menus. The lack of incentives and support for family farming, lack of access to markets, and fragile logistics operations, including marketing, distribution, transportation, and delivery, are the main causes of the difficulties encountered in acquiring local foods for school feeding programs.

Additionally, we highlight that the inclusion of farmers in cooperatives and associations can be an effective solution to improve the logistics infrastructure of the supply chain for schools. However, for this option to be viable as a market alternative, more financial and political incentives for the family farming sector are necessary. In this way, the supply of local foods for national programs becomes a more attractive option for farmers.

It must be considered that in our analysis there is a higher concentration of studies related to the Farm to School Program and PNAE, as we understand that these programs are older, more structured, and successful. Thus, there is a lack of diversity of experiences in this approach and also a gap in publications that portray these scenarios, especially in low-income countries. Furthermore, we suggest more empirical studies that evaluate the impact of these practices on national programs and examine the logistics of the supply chain in schools. We hope that our study can shed light on the limitations surrounding the inclusion of local foods in national school feeding programs and contribute to the reformulation of agricultural and food policies that aim to increase the participation of farmers in this market niche.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su15042863/s1, File S1: PRISMA Checklist; File S2: Research strategy for systematic review.

Author Contributions

V.M.C., S.M.G. and M.C.M.J. participated in all phases of the study. C.R. participated in the study analysis, writing and critically reviewing the intellectual content. J.B.A.d.C. contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2021: Making Agrifood Systems More Resilient to Shocks and Stresses; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IFAD. United Nations Decade of Family Farming 2019–2028. Global Action Plan; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ca4672en/ca4672en.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- FAO. World Food and Agriculture—Statistical Pocketbook 2021; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowder, S.K.; Sánchez, M.V.; Bertini, R. Farms, Family Farms, Farmland Distribution and Farm Labour: What Do We Know Today? FAO—Agricultural Development Economics Working Paper: Rome, Italy, 2019; ISBN 978-92-5-131970-3. [Google Scholar]

- Shete, M.; Rutten, M. Impacts of Large-Scale Farming on Local Communities’ Food Security and Income Levels—Empirical Evidence from Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Land Use Policy 2015, 47, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tscharntke, T.; Clough, Y.; Wanger, T.C.; Jackson, L.; Motzke, I.; Perfecto, I.; Vandermeer, J.; Whitbread, A. Global Food Security, Biodiversity Conservation and the Future of Agricultural Intensification. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 151, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, D.F.; Muraoka, R.; Otsuka, K. Why African Rural Development Strategies Must Depend on Small Farms. Glob. Food Secur. 2016, 10, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittonell, P.; Fernandez, M.; El Mujtar, V.E.; Preiss, P.V.; Sarapura, S.; Laborda, L.; Mendonça, M.A.; Alvarez, V.E.; Fernandes, G.B.; Petersen, P.; et al. Emerging Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis from Family Farming and the Agroecology Movement in Latin America—A Rediscovery of Food, Farmers and Collective Action. Agric. Syst. 2021, 190, 103098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibhatu, K.T.; Qaim, M. Rural Food Security, Subsistence Agriculture, and Seasonality. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2014—Innovation in Family Farming; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014; ISBN 978-92-5-108536-3. [Google Scholar]

- Graeub, B.E.; Chappell, M.J.; Wittman, H.; Ledermann, S.; Kerr, R.B.; Gemmill-Herren, B. The State of Family Farms in the World. World Dev. 2016, 87, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Food Programme. State of School Feeding Worldwide 2020; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2020; ISBN 978-92-95050-00-6. [Google Scholar]

- Scialabba, N. Food Wastage Footprint & Climate Change; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015; Available online: https://www.fao.org/nr/sustainability/food-loss-and-waste (accessed on 27 November 2022).

- Global Panel. Healthy Meals in Schools: Policy Innovations Linking Agriculture, Food Systems and Nutrition. Policy Brief; Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020: Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Healthy Diets; The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI)—FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO: Rome, Italy, 2020; ISBN 978-92-5-132901-6. [Google Scholar]

- Botkins, E.R.; Roe, B.E. Understanding Participation in Farm to School Programs: Results Integrating School and Supply-Side Factors. Food Policy 2018, 74, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, A.L.D.; Trentini, T.; Nishida, W.; Rossi, C.E.; Costa, L.D.F.; de Vasconcelos, F.D.G.; de Andrade Castellani, A.L.; Trentini, T.; Nishida, W.; Rossi, C.E.; et al. Purchase of Family Farm and Organic Foods by the Brazilian School Food Program in Santa Catarina State, Brazil. Braz. J. Nutr. 2017, 30, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triches, R.M.; Schneider, S. School feeding and family farming: Reconnecting consumption to production. Saúde E Soc. 2010, 19, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, V.M.; Pinheiro, L.G.B.; das Neves, R.A.M.; de Araujo, M.A.D.; da Silva, J.B.; Bezerra, P.E.R.; Jacob, M.C.M.; Chaves, V.M.; Bacurau Pinheiro, L.G.; das Neves, R.A.; et al. Challenges to Balance Food Demand and Supply: Analysis of PNAE Execution in One Semiarid Region of Brazil. Desenvolv. E Meio Ambiente 2020, 55, 470–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.M.; Barbosa, R.M.S.; Finizola, N.C.; Soares, D.d.S.B.; Henriques, P.; Pereira, S.; Carvalhosa, C.S.; Siqueira, A.B.F.S.; Dias, P.C. Perception of the Operating Agents about the Brazilian National School Feeding Program. Rev. Saude Publica 2019, 53, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramer, W.M.; Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kleijnen, J.; Franco, O.H. Optimal Database Combinations for Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews: A Prospective Exploratory Study. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for Prevalence Studies; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, C.K.-L.; Mertz, D.; Loeb, M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: Comparing Reviewers’ to Authors’ Assessments. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NMKL. Analytical Quality Control—Guidelines for the Publication of Analytical Results of Chemical Analyses in Foodstuffs; Nordic Committee on Food Analysis: Bergen, Norway, 2011; Available online: https://studylib.net/doc/18260137/analytical-quality-control---guidelines-for-the-publicati (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Jacob, M.C.M.; Araujo de Medeiros, M.F.; Albuquerque, U.P. Biodiverse Food Plants in the Semiarid Region of Brazil Have Unknown Potential: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izumi, B.T.; Rostant, O.S.; Moss, M.J.; Hamm, M.W. Results from the 2004 Michigan Farm-to-School Survey. J. Sch. Health 2006, 76, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccarin, J.G.; Triches, R.M.; Teo, C.R.P.A.; da Silva, D.B.P. Indicadores de Avaliação Das Compras Da Agricultura Familiar Para Alimentação Escolar No Paraná, Santa Catarina e São Paulo. Rev. Econ. Sociol. Rural 2017, 55, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, A.; Mendis, S.S. Too Cool for Farm to School? Analyzing the Determinants of Farm to School Programming Continuation. Food Policy 2021, 102, 102045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, C.L.; Rombach, M.; Haring, A.M.; Bitsch, V.; Braun, C.L.; Rombach, M.; Haering, A.M.; Bitsch, V. A Local Gap in Sustainable Food Procurement: Organic Vegetables in Berlin’s School Meals. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.S.; e Silva, D.O. Prospects of Food and Nutritional Security in the Tijuaçu Quilombo, Brazil: Family Agricultural Production for School Meals. Interface Commun. Health Educ. 2014, 18, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.O.; Jablonski, B.B.R.; O’Hara, J.K. School Districts and Their Local Food Supply Chains. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2017, 34, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colasanti, K.J.A.; Matts, C.; Hamm, M.W. Results from the 2009 Michigan Farm to School Survey: Participation Grows from 2004. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverio, G.d.A.; de Sousa, A.A. Organic Foods from Family Farms in the National School Food Program: Perspectives of Social Actors from Santa Catarina, Brazil. Rev. Nutr. 2014, 27, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, V.M.G.; Villar, B.S. Acquisition of Family Farm Foods in Municipalities of São Paulo State: The Influence of the Management of the School Feeding Program and Municipal Characteristics. Rev. Nutr. 2019, 32, e180083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Anjos, I.A.; Lopes, J.D.; Horta, P.M.; dos Anjos, I.A.; Lopes Filho, J.D.; Horta, P.M. Factors Associated with the Purchase of Family Farming Products for National School Feeding Program in Minas Gerais in 2017, Brazil. Cienc. Rural 2022, 52, e20200776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elolu, S.; Ongeng, D. Community-Based Nutrition-Sensitive Approach to Address Short-Term Hunger and Undernutrition among Primary School Children in Rural Areas in a Developing Country Setting: Lessons from North and North-Eastern Uganda. BMC Nutr. 2020, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimmons, J.; O’Hara, J.K. Market Channel Procurement Strategy and School Meal Costs in Farm-to-School Programs. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2019, 48, 388–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giombi, K.; Joshi, A.; Rains, C.; Wiecha, J. Farm-to-School Grant Funding Increases Children’s Access to Local Fruits and Vegetables in Oregon. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2020, 9, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, A.E.; Davis, S.; Sandolo, C.; Gaudet, N.; Castrogivanni, B. Formative Research to Create a Farm-to-School Program for High School Students in a Lower Income, Diverse, Urban Community. J. Sch. Health 2018, 88, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izumi, B.T.; Wynne Wright, D.; Hamm, M.W. Market Diversification and Social Benefits: Motivations of Farmers Participating in Farm to School Programs. J. Rural Stud. 2010, 26, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, B.T.; Alaimo, K.; Hamm, M.W. Farm-to-School Programs: Perspectives of School Food Service Professionals. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2010, 42, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnerd, M.E.; Sacheck, J.M.; Griffin, T.S.; Goldberg, J.P.; Cash, S.B.; Lehnerd, M.E.; Sacheck, J.M.; Griffin, T.S.; Goldberg, J.P.; Cash, S.B. Farmers’ Perspectives on Adoption and Impacts of Nutrition Incentive and Farm to School Programs. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2018, 8, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, A.B.; Jablonski, B.B.R.; Costanigro, M.; Frasier, W.M. The Impact of State Farm to School Procurement Incentives on School Purchasing Decisions. J. Sch. Health 2021, 91, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, A.C.; Steiner, A.S.; Houser, R.F. Do State Farm-to-School–Related Laws Increase Participation in Farm-to-School Programs? J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2017, 12, 466–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, J.K.; Benson, M.C. The Impact of Local Agricultural Production on Farm to School Expenditures. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2017, 34, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, J.K.; McClenachan, L. Factors Influencing ‘Sea to School’ Purchases of Local Seafood Products. Mar. Policy 2019, 100, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinard, C.A.; Smith, T.M.; Carpenter, L.R.; Chapman, M.; Balluff, M.; Yaroch, A.L. Stakeholders’ Interest in and Challenges to Implementing Farm-to-School Programs, Douglas County, Nebraska, 2010–2011. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2013, 10, E210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockett, F.C.; Corrêa, R.d.S.; Pires, G.C.; Machado, L.d.S.; Hoerlle, F.S.; Souza, C.P.M.D.; de Oliveira, A.B.A. Family Farming and School Meals in Rio Grande Do Sul, Brazil. Cienc. Rural 2019, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plakias, Z.T.; Klaiber, H.A.; Roe, B.E.; Plakias, Z.T.; Klaiber, H.A.; Roe, B.E. Trade-Offs in Farm-to-School Implementation: Larger Foodsheds Drive Greater Local Food Expenditures. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2020, 45, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafft, K.; Hinrichs, C.C.; Bloom, J.D. Pennsylvania Farm-to-School Programs and the Articulation of Local Context. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2010, 5, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaibu, A.F.; Al-Hassan, R.M. Accessibility of Rice Farmers to the Ghana School Feeding Programme and Its Effect on Output. AGRIS Online Pap. Econ. Inform. 2015, 7, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaibu, A.F.; Al-hassan, R.M. Analysis of Factors Influencing Caterers of the Ghana School Feeding Programme to Purchase Rice from Local Farmers in the Tamale Metropolis, Tolon-Kumbungu and Karaga Districts. AGRIS Online Pap. Econ. Inform. 2014, 6, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Wleklinski, D.; Roth, S.L.; Tragoudas, U. Does School Size Affect Interest for Purchasing Local Foods in the Midwest? Child Obes. 2013, 9, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, P.; Suárez-Mercader, S.; Comino, I.; Martínez-Milán, M.A.; Cavalli, S.B.; Davó-Blanes, M.C. Facilitating Factors and Opportunities for Local Food Purchases in School Meals in Spain. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, P.; Caballero, P.; Davó-Blanes, M.C. Purchase of local foods for school meals in Andalusia, the Canary Islands and the Principality of Asturias (Spain). Gac. Sanit. 2017, 31, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, P.; Martinelli, S.S.; Melgarejo, L.; Cavalli, S.B.; Davó-Blanes, M.C. Using Local Family Farm Products for School Feeding Programmes: Effect on School Menus. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 1289–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, P.; Martinelli, S.S.; Melgarejo, L.; Davó-Blanes, M.C.; Cavalli, S.B. Strengths and Weaknesses in the Supply of School Food Resulting from the Procurement of Family Farm Produce in a Municipality in Brazil. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2015, 20, 1891–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.J.; Brawner, A.J.; Kaila, U. “You Can’t Manage with Your Heart”: Risk and Responsibility in Farm to School Food Safety. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virta, A.; Love, D.C. Assessing Fish to School Programs at 2 School Districts in Oregon. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2020, 7, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehring, R.; Miranda, A.; Howe, A. Making the Case for Institutional Demand: Supporting Smallholders through Procurement and Food Assistance Programmes. Glob. Food Secur. 2017, 12, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HLPE. Investing in Smallholder Agriculture for Food Security. A Report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security; High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Birner, R.; Resnick, D. The Political Economy of Policies for Smallholder Agriculture. World Dev. 2010, 38, 1442–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiellaro, J.R.; dos Reis, J.G.M.; Palacios-Argüello, L.; Muçouçah, F.J.; Vendrametto, O. Food distribution in school feeding programmes in Brazil. In Food Supply Chains in Cities: Modern Tools for Circularity and Sustainability; Aktas, E., Bourlakis, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 265–288. ISBN 978-3-030-34065-0. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, H.H.; Selfa, T.; Janke, R. Barriers and Opportunities for Sustainable Food Systems in Northeastern Kansas. Sustainability 2010, 2, 232–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelli, A.; Masset, E.; Folson, G.; Kusi, A.; Arhinful, D.K.; Asante, F.; Ayi, I.; Bosompem, K.M.; Watkins, K.; Abdul-Rahman, L.; et al. Evaluation of Alternative School Feeding Models on Nutrition, Education, Agriculture and Other Social Outcomes in Ghana: Rationale, Randomised Design and Baseline Data. Trials 2016, 17, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belik, W.; Fornazier, A. Chapter three—Public policy and the construction of new markets to family farms: Analyzing the case of school meals in São Paulo, Brazil. In Advances in Food Security and Sustainability; Barling, D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios-Argüello, L.; dos Reis, J.G.M.; Maiellaro, J.R. Supplying school canteens with organic and local products: Comparative analysis. In Advances in Production Management Systems. Smart Manufacturing and Logistics Systems: Turning ideas into Action; Kim, D.Y., von Cieminski, G., Romero, D., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, A.; Holcomb, R.B. Impacts of School District Characteristics on Farm-to-School Program Participation: The Case for Oklahoma. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2011, 42, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippini, R.; De Noni, I.; Corsi, S.; Spigarolo, R.; Bocchi, S. Sustainable School Food Procurement: What Factors Do Affect the Introduction and the Increase of Organic Food? Food Policy 2018, 76, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, P.; Davó-Blanes, M.C.; Martinelli, S.S.; Melgarejo, L.; Cavalli, S.B. The Effect of New Purchase Criteria on Food Procurement for the Brazilian School Feeding Program. Appetite 2017, 108, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, C.R.P.A. The partnership between the Brazilian School Feeding Program and family farming: A way for reducing ultra-processed foods in school meals. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, M.B.; Thilsted, S.H.; Kjellevold, M.; Overå, R.; Toppe, J.; Doura, M.; Kalaluka, E.; Wismen, B.; Vargas, M.; Franz, N. Locally-Procured Fish Is Essential in School Feeding Programmes in Sub-Saharan Africa. Foods 2021, 10, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beintema, J.J.S.; Gallego-Castillo, S.; Londoño-Hernandez, L.F.; Restrepo-Manjarres, J.; Talsma, E.F. Scaling-up Biofortified Beans High in Iron and Zinc through the School-Feeding Program: A Sensory Acceptance Study with Schoolchildren from Two Departments in Southwest Colombia. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 1138–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Milán, M.A.; Davó-Blanes, M.C.; Comino, I.; Caballero, P.; Soares, P. Sustainable and Nutritional Recommendations for the Development of Menus by School Food Services in Spain. Foods 2022, 11, 4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Nutrition Guidelines and Standards for School Meals. A Report from 33 Low and Middle-Income Countries; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/CA2773EN/ca2773en.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- World Food Programme. State of School Feeding Worldwide 2013; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2013; Available online: https://www.wfp.org/publications/state-school-feeding-worldwide-2013 (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Cupertino, A.; Ginani, V.; Cupertino, A.P.; Botelho, R.B.A. School Feeding Programs: What Happens Globally? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz, J.; Smetschka, B.; Grima, N. Farmer Cooperation as a Means for Creating Local Food Systems—Potentials and Challenges. Sustainability 2017, 9, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossmann, M.P.; Teo, C.R.P.A.; Busato, M.A.; Triches, R.M. Interface between Family Farming and School Feeding: Barriers and Coping Mechanisms from the Perspective of Different Social Actors in Southern Brazil. Rev. De Econ. E Sociol. Rural 2017, 55, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehinde, A.D.; Adeyemo, R.; Ogundeji, A.A. Does Social Capital Improve Farm Productivity and Food Security? Evidence from Cocoa-Based Farming Households in Southwestern Nigeria. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluyole, K.A.; Taiwo, O. Socio-Economic Variables and Food Security Status of Cocoa Farming Households in Ondo State, Nigeria. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2016, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, S.J.; Aggarwal, P.K.; Ainslie, A.; Angelone, C.; Campbell, B.M.; Challinor, A.J.; Hansen, J.W.; Ingram, J.S.I.; Jarvis, A.; Kristjanson, P.; et al. Options for Support to Agriculture and Food Security under Climate Change. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 15, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC—Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Food security. In Climate Change and Land: IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 437–550. ISBN 978-1-00-915798-8. [Google Scholar]

- Paloviita, A.; Järvelä, M. Climate Change Adaptation and Food Supply Chain Management; Routledge: London UK, 2015; Volume 1, ISBN 978-1-315-75772-8. [Google Scholar]

- Verguet, S.; Limasalle, P.; Chakrabarti, A.; Husain, A.; Burbano, C.; Drake, L.; Bundy, D.A.P. The Broader Economic Value of School Feeding Programs in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Estimating the Multi-Sectoral Returns to Public Health, Human Capital, Social Protection, and the Local Economy. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 587046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundy, D.A.P.; de Silva, N.; Horton, S.; Jamison, D.T.; Patton, G.C. Re-Imagining School Feeding: A High-Return Investment in Human Capital and Local Economies; Child and Adolescent Health and Development; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dyngeland, C.; Oldekop, J.A.; Evans, K.L. Assessing Multidimensional Sustainability: Lessons from Brazil’s Social Protection Programs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 20511–20519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).