The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Citizens’ Attitudes and Behaviors in the Use of Peri-Urban Forests: An Experience from Italy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

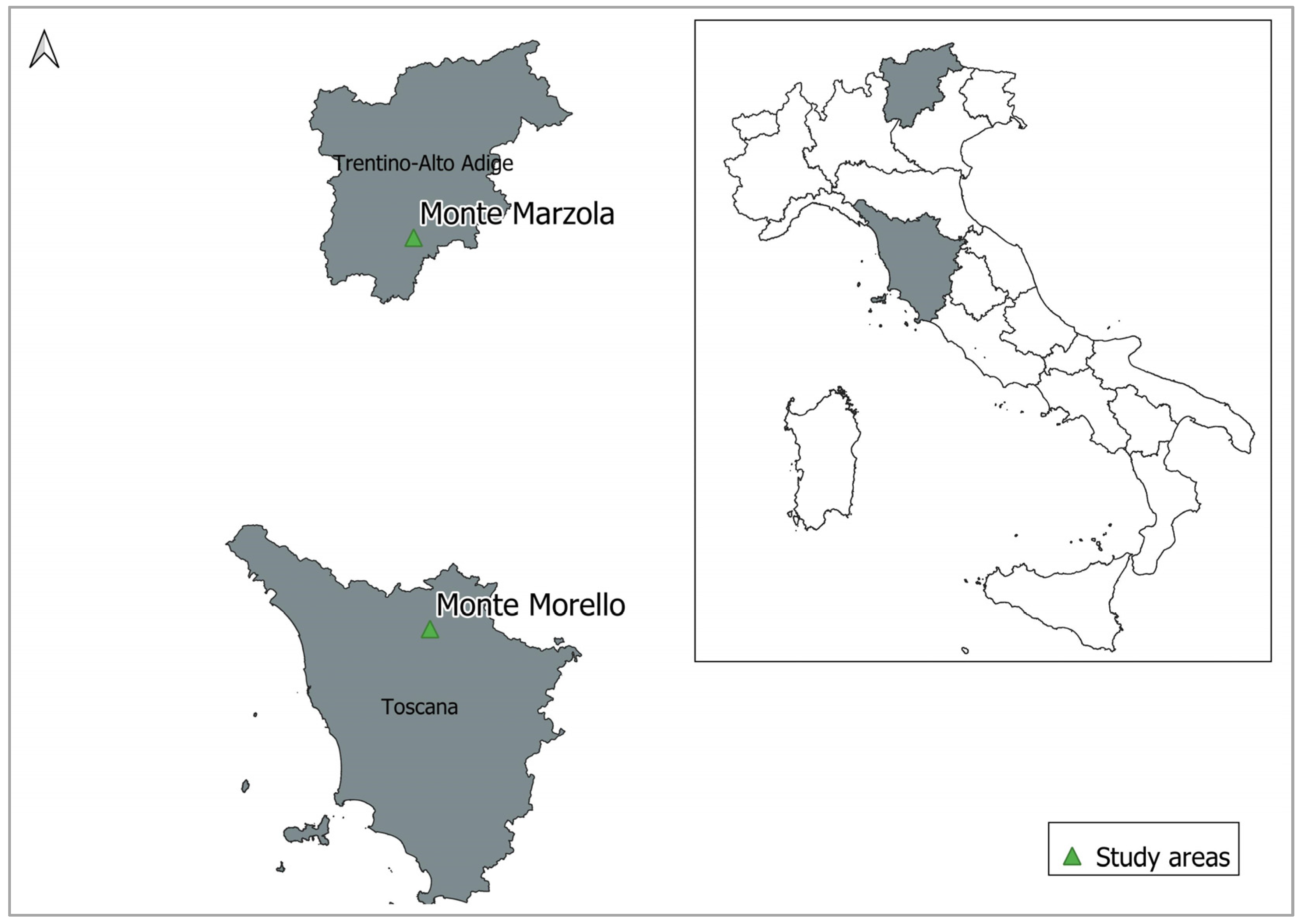

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Research Framework

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

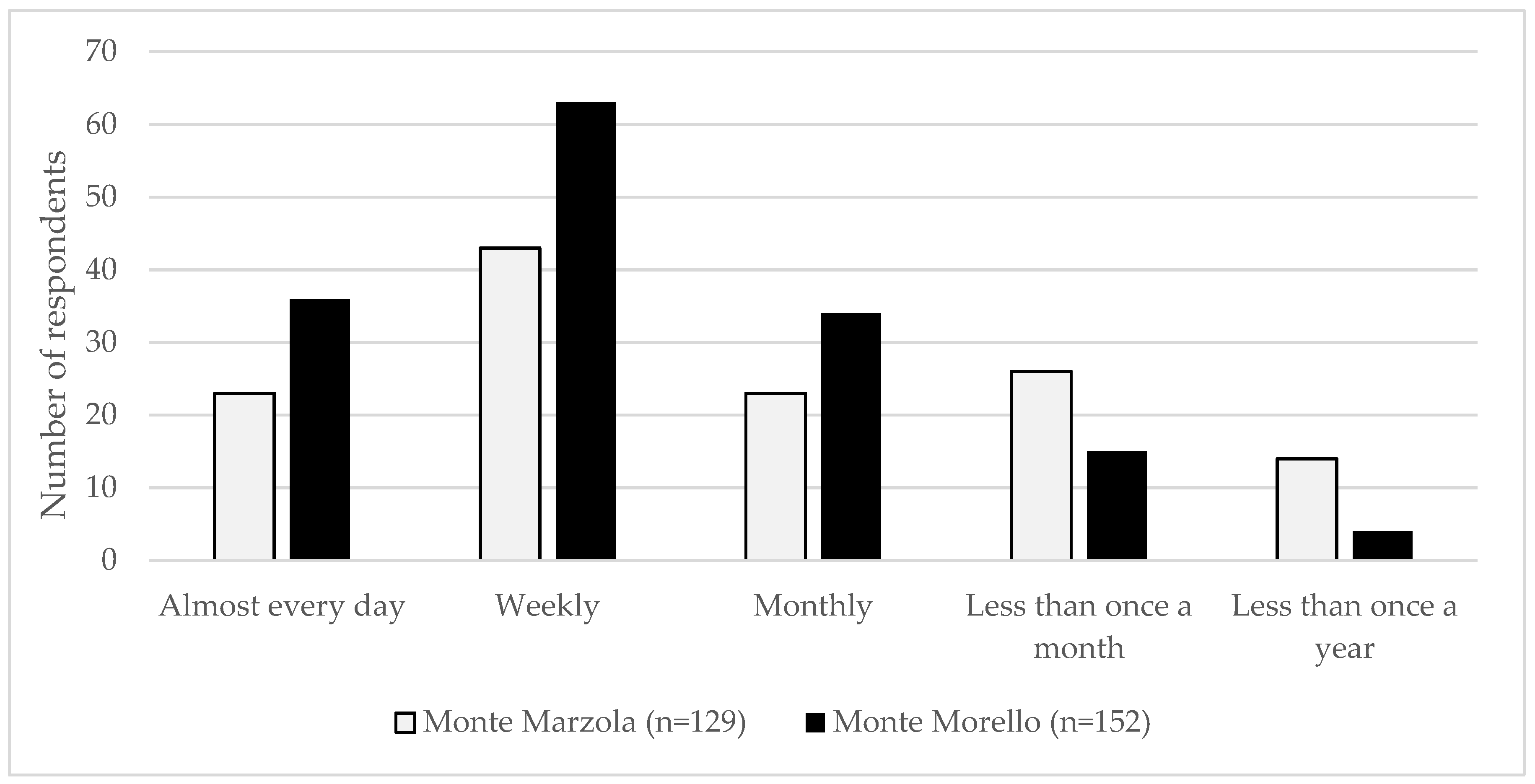

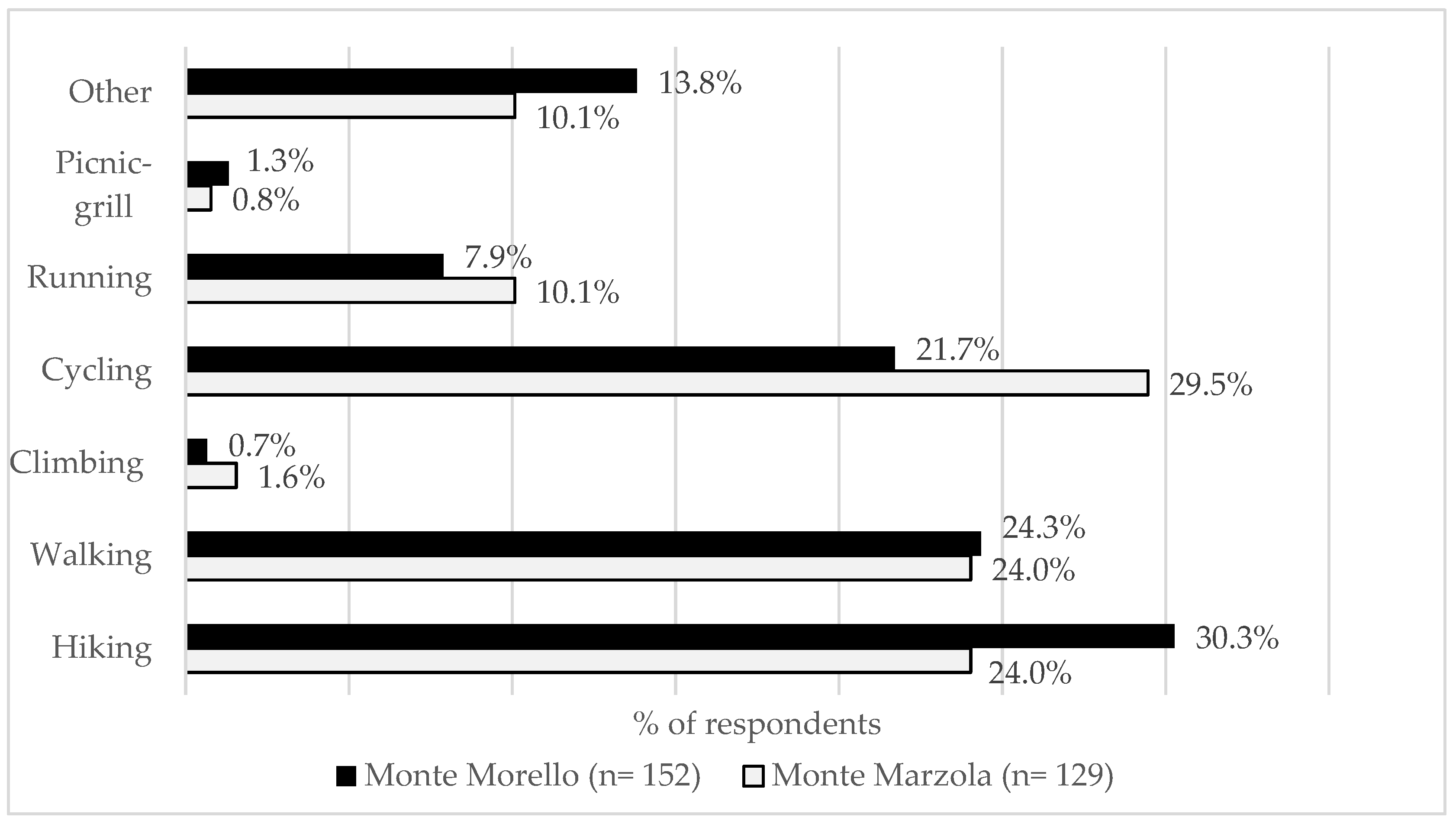

3.2. Impact of Pandemic on Visitors’ Use and Activities in the Forests

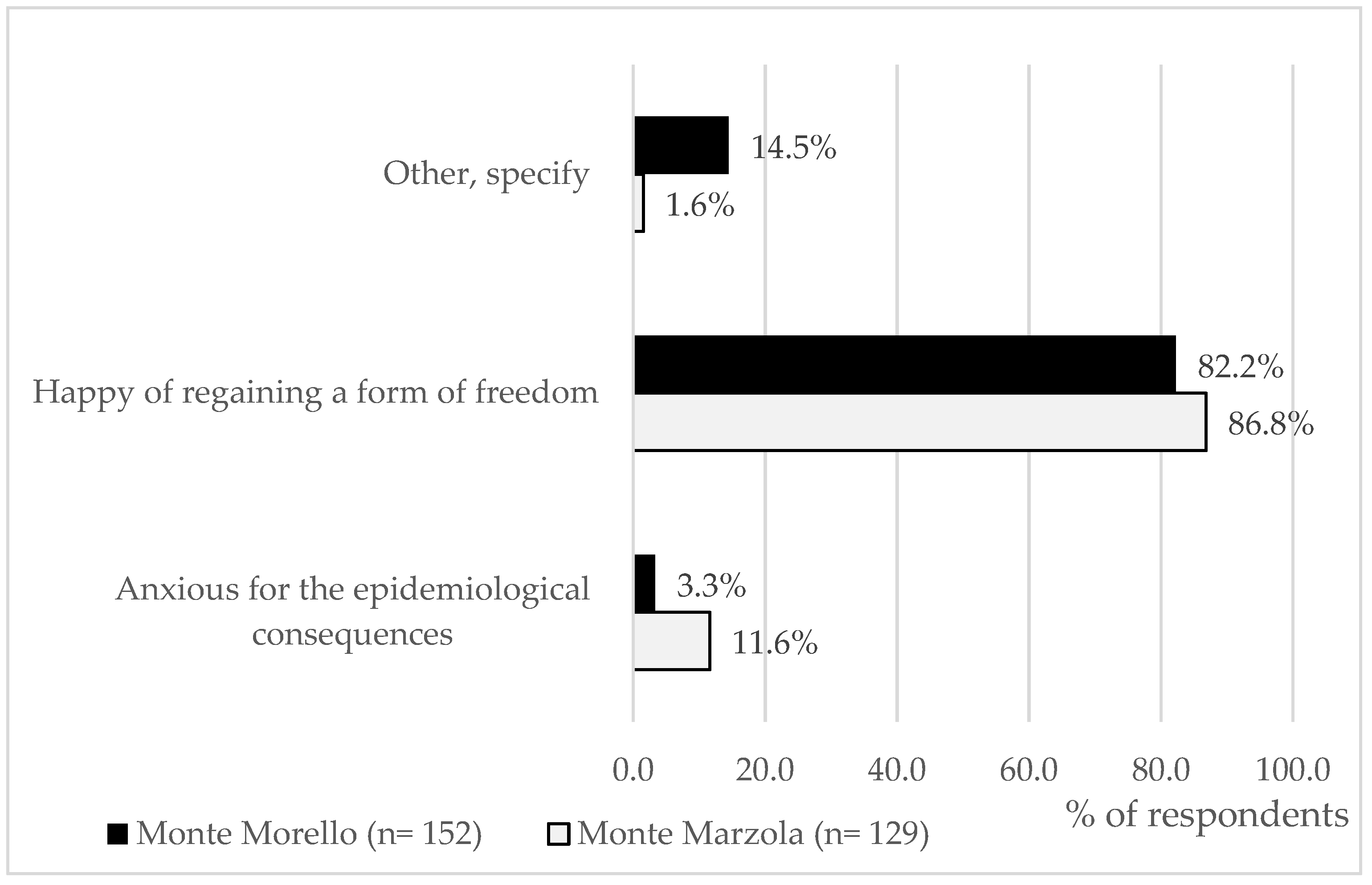

3.3. Needs and Feelings Visiting Forests during the COVID-19 Pandemic

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Urban and Peri-Urban Forestry. Definition; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: http://www.fao.org/forestry/urbanforestry/87025/en/ (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Livesley, S.J.; Escobedo, F.J.; Morgenroth, J. The Biodiversity of Urban and Peri-Urban Forests and the Diverse Ecosystem Services They Provide as Socio-Ecological Systems. Forests 2016, 7, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larabi, F.; Berrichi, M.; Paletto, A. Social Demand for Ecosystem Services Provided by Peri-Urban Forests: The Case Study of the Tlemcen Forest (Algeria). J. Environ. Account. Manag. 2021, 9, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Oncescu, J. Rural restructuring and its impact on community recreation opportunities. Ann. Leis. Res. 2015, 18, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitson, D. Leisure, consumption, and the remaking of “community”. Leisure/Loisir 2006, 30, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletto, A.; Guerrini, S.; De Meo, I. Exploring visitors’ perceptions of silvicultural treatments to increase the destination attractiveness of peri-urban forests: A case study in Tuscany Region (Italy). Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 27, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, G.; Abildtrup, J.; Garcia, S. Preferences for urban green spaces and peri-urban forests: An analysis of stated residential choices. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 148, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrus, G.; Scopelliti, M.; Lafortezza, R.; Colangelo, G.; Ferrini, F.; Salbitano, F.; Agrimi, M.; Portoghesi, L.; Semenzato, P.; Sanesi, G. Go greener, feel better? The positive effects of biodiversity on the well-being of individuals visiting urban and peri-urban green areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 134, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauru, K.; Lehvävirta, S.; Korpela, K.; Kotze, D.J. Closure of view to the urban matrix has positive effects on perceived restorativeness in urban forests in Helsinki, Finland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 107, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinette, C.; Gary, O. Plants People and Environmental Quality; USA Department of the Interior National Park Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1972.

- Andrada, R., II; Deng, J.; Gazal, K. Exploring people’s preferences on specific attributes of urban forests in Washington DC: A conjoint approach. J. Hortic. For. 2015, 7, 200–209. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organitation (FAO). Global Forest Resources Assessment 2005–Progress towards Sustainable Forest Management; FAO Forestry Paper No. 147; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2005; Available online: www.fao.org/docrep/008/a0400e/a0400e00.htm (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- de Vries, S.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Natural environments—Healthy environments? An exploratory analysis of the relationship between greenspace and health. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 1717–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, O.; Russo, A. Assessing the contribution of urban green spaces in green infrastructure strategy planning for urban ecosystem conditions and services. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 68, 102772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, L.; Pauleit, S.; Seeland, K.; de Vries, S. Benefits and Uses of Urban Forests and Trees. In Urban Forests and Trees; Konijnendijk, C., Nilsson, K., Randrup, T., Schipperijn, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, J.; Pretty, J. What is the best dose of nature and green exercise for improving mental health? A multi-study analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3947–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, L.; Morris, J.; Stewart, A. Engaging with peri-urban woodlands in England: The contribution to people’s health and well-being and implications for future management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public health 2014, 11, 6171–6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, L.; Hotte, N.; Barron, S.; Cowan, J.; Sheppard, S.R. The social and economic value of cultural ecosystem services provided by urban forests in North America: A review and suggestions for future research. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 25, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E.; Tengö, M.; McPhearson, T.; Kremer, P. Cultural ecosystem services as a gateway for improving urban sustainability. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 12, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, V. The urbanization process and economic growth: The so-what question. J. Econ. Growth 2003, 8, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Strengthening Preparedness for COVID-19 in Cities and Urban Settings: Interim Guidance for Local Authorities; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Da Schio, N.; Phillips, A.; Fransen, K.; Wolff, M.; Haase, D.; Krajter Ostoić, S.; Živojinović, I.; Vuletić, D.; Derks, J.; Davies, C.; et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use of and attitudes towards urban forests and green spaces: Exploring the instigators of change in Belgium. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 65, 127305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, B.; Kennedy, C.; Field, C.; McPhearson, T. Who benefits from urban green spaces during times of crisis? Perception and use of urban green spaces in New York City during the COVID-19 pandemic. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 65, 127354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atalan, A. Is the lockdown important to prevent the COVID-19 pandemic? Effects on psychology, environment and economy-perspective. Ann. Med. Surg. 2020, 56, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, R.C.; Cicinelli, M.V.; Gilbert, S.S.; Honavar, S.G.; Murthy, G.V. COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons learned and future directions. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 68, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Freedman, D.O. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: Pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; Mayr, V.; Dobrescu, A.I.; Chapman, A.; Persad, E.; Klerings, I.; Wagner, G.; Siebert, U.; Christof, C.; Zachariah, C.; et al. Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID-19: A rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 4, CD013574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Güner, H.R.; Hasanoğlu, İ.; Aktaş, F. COVID-19: Prevention and control measures in community. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 50, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, R.; Dranitsaris, G.; Mubashir, T.; Bartoszko, J.; Riazi, S. A country level analysis measuring the impact of government actions, country preparedness and socioeconomic factors on COVID-19 mortality and related health outcomes. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 25, 100464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchiyama, Y.; Kohsaka, R. Access and use of green areas during the COVID-19 pandemic: Green infrastructure management in the “New Normal”. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honey-Rosés, J.; Anguelovski, I.; Chireh, V.K.; Daher, C.; Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C.; Litt, J.S.; Mawani, V.; McCall, M.K.; Orellana, A.; Oscilowicz, E.; et al. The impact of COVID-19 on public space: An early review of the emerging questions–design, perceptions and inequities. Cities Health 2021, 5, S263–S279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.; Eykelbosh, A. COVID-19 and Outdoor Safety: Considerations for Use of Outdoor Recreational Spaces; National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Callaway, E. Beyond Omicron: What’s next for COVID’s viral evolution. Nature 2021, 600, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.; Pant, A.B. Mitigating COVID-19 in the face of emerging virus variants, breakthrough infections and vaccine hesitancy. J. Autoimmun. 2022, 127, 102792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kerkhove, M.D. COVID-19 in 2022: Controlling the pandemic is within our grasp. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiston, P.; Kashyap, R.; Rotondi, V. Reliance on scientists and experts during an epidemic: Evidence from the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. SSM Popul. Health 2021, 13, 100721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barari, S.; Caria, S.; Davola, A.; Falco, P.; Fetzer, T.; Fiorin, S.; Hensel, L.; Ivchenko, A.; Jachimowicz, J.; King, G.; et al. Evaluating COVID-19 public health messaging in Italy: Self-reported compliance and growing mental health concerns. MedRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, F.; Massetti, L.; Calaza-Martínez, P.; Cariñanos, P.; Dobbs, C.; Ostoić, S.K.; Marin, A.M.; Pearlmutter, D.; Saaroni, H.; Šaulienė, I.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use and perceptions of urban green space: An international exploratory study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 56, 126888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nützel, A.; Schulbert, C. Facies of two important Early Triassic gastropod lagerstätten: Implications for diversity patterns in the aftermath of the end-Permian mass extinction. Facies 2005, 51, 480–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieratti, E.; Paletto, A.; De Meo, I.; Fagarazzi, C.; Rillo Migliorini Giovannini, M. Assessing the forest-wood chain at local level: A Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) based on the circular bioeconomy principles. Ann. For. Res. 2019, 62, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantiani, P.; Chiavetta, U. Estimating the mechanical stability of Pinus nigra Arn. using an alternative approach across several plantations in central Italy. iForest 2015, 8, 846–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meo, I.; Agnelli, E.A.; Graziani, A.; Kitikidou, K.; Lagomarsino, A.; Milios, E.; Radoglou, K.; Paletto, A. Deadwood volume assessment in Calabrian pine (Pinus brutia Ten.) peri-urban forests: Comparison between two sampling methods. J. Sustain. For. 2017, 36, 666–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Huitrón, N.M.; Naranjo, E.J.; Santos-Fita, D.; Estrada-Lugo, E. The Importance of Human Emotions for Wildlife Conservation. Front. Phycol. 2020, 11, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, L.; Chen, C.; Haase, D. The interaction between human demand and urban greenspace supply for promoting positive emotions with sentiment analysis from twitter. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 78, 127763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorella, F.; Santoni, S.; Notaro, S.; Paletto, A. The social perception of forest landscape in Trentino-Alto Adige: Comparison among case studies. Forest 2016, 13, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notaro, S.; Grilli, G.; Paletto, A. The role of emotions on tourists’ willingness to pay for the Alpine landscape: A latent class approach. Landsc. Res. 2019, 44, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann-Wübbelt, A.; Fricke, A.; Sebesvari, Z.; Yakouchenkova, I.A.; Fröhlich, K.; Saha, S. High public appreciation for the cultural ecosystem services of urban and peri-urban forests during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kičić, M.; Haase, D.; Marin, A.M.; Vuletić, D.; Ostoić, S.K. Perceptions of cultural ecosystem services of tree-based green infrastructure: A focus group participatory mapping in Zagreb, Croatia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 78, 127767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletto, A.; De Meo, I.; Grilli, G.; Notaro, S. Valuing nature-based recreation in forest areas in Italy: An application of Travel Cost Method (TCM). J. Leis. Res. 2022, 54, 26–45. [Google Scholar]

- Grima, N.; Corcoran, W.; Hill-James, C.; Langton, B.; Sommer, H.; Fisher, B. The importance of urban natural areas and urban ecosystem services during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, J.; Giessen, L.; Winkel, G. COVID-19-induced visitor boom reveals the importance of forests as critical infrastructure. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Barton, D.N.; Gundersen, V.; Figari, H.; Nowell, M. Urban nature in a time of crisis: Recreational use of green space increases during the COVID-19 outbreak in Oslo, Norway. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meo, I.; Becagli, C.; Cantiani, M.G.; Casagli, A.; Paletto, A. Citizens’ use of public urban green spaces at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 77, 127739. [Google Scholar]

- De Miranda, D.M.; da Silva Athanasio, B.; Oliveira, A.C.S.; Simoes-e-Silva, A.C. How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fegert, J.M.; Vitiello, B.; Plener, P.L.; Clemens, V. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horká, H.; Zdeněk, H. The Ecotherapeutic Potential of Nature and Taking Care of Ones’ Health. In School and Health 21. Papers on Health; Řehulka, E., Ed.; Masaryk University: Brno, Czech Republic, 2010; pp. 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, W.L.; Meyer, C.; Lawhon, B.; Taff, B.D.; Mateer, T.; Reigner, N.; Newman, P. The COVID-19 Pandemic is Changing the Way People Recreate Outdoors: Preliminary Report on a National Survey of Outdoor Enthusiasts Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic; The Pennsylvania State University Department of Recreation, Park, and Tourism Management: University Park, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Weinbrenner, H.; Breithut, J.; Hebermehl, W.; Kaufmann, A.; Klinger, T.; Palm, T.; Wirth, K. The Forest Has Become Our New Living Room—The Critical Importance of Urban Forests During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2021, 4, 672909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, S.; Deschacht, N. Public Awareness of Nature and the Environment During the COVID-19 Crisis. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 76, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brida, J.G.; Osti, L.; Faccioli, M. Residents’ perception and attitudes towards tourism impacts: A case study of the small rural community of Folgaria (Trentino—Italy). Benchmarking Int. J. 2011, 18, 359–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletto, A.; De Meo, I.; Cantiani, M.G.; Maino, F. Social perceptions and forest management strategies in an Italian Alpine community. Mt. Res. Dev. 2013, 33, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, G.P.; Provost, C. Measurement of cultural complexity. Ethnology 1973, 12, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Emotions | Description |

|---|---|

| Restlessness | the state of being unable to stay still or be happy where you are, because you are bored or need a change. |

| Familiarity | the state of knowing somebody/something well; the state of recognizing somebody/something. |

| Physical wellbeing | general health and happiness. |

| Harmony | a state of peaceful existence and agreement. |

| Safety | the state of being safe and protected from danger or harm. |

| Freedom | the power or right to do or say what you want without anyone stopping you. |

| Isolation | the act of separating somebody/something; the state of being separate. |

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics/Study Area | Monte Marzola (n = 129) | Monte Morello (n = 152) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | ||

| Male | 67.4 | 73.7 |

| Female | 32.6 | 26.3 |

| Age (%) | ||

| Less than 20 years old | 6.2 | 4.6 |

| 21–30 years old | 14.7 | 19.1 |

| 31–40 years old | 20.2 | 25.0 |

| 41–50 years old | 19.4 | 14.5 |

| 51–60 years old | 20.9 | 20.4 |

| 61–70 years old | 13.2 | 11.8 |

| More than 70 years old | 5.4 | 4.6 |

| Level of education (%) | ||

| Elementary/technical school degree | 13.2 | 7.9 |

| High school degree | 42.6 | 49.3 |

| University/post-university degree | 44.2 | 42.8 |

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics/Change of Frequency | Increased | Decreased | Unchanged | New Area Discovered during the Pandemic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monte Marzola (n = 129) | ||||

| Gender (%) | ||||

| Male | 40.2 | 13.8 | 37.9 | 8.0 |

| Female | 28.6 | 9.5 | 54.8 | 7.1 |

| Age (%) | ||||

| Less than 20 years old | 62.5 | 0.0 | 37.5 | 0.0 |

| 21–30 years old | 31.6 | 10.5 | 31.6 | 26.3 |

| 31–40 years old | 42.3 | 11.5 | 46.2 | 0.0 |

| 41–50 years old | 24.0 | 12.0 | 60.0 | 4.0 |

| 51–60 years old | 44.4 | 11.1 | 44.5 | 0.0 |

| 61–70 years old | 23.5 | 23.5 | 41.2 | 11.8 |

| More than 70 years old | 42.8 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 28.6 |

| Level of education (%) | ||||

| Elementary/technical school degree | 42.1 | 10.5 | 42.1 | 5.3 |

| High school degree | 36.4 | 12.7 | 43.6 | 7.3 |

| University/post-university degree | 34.5 | 12.7 | 43.6 | 9.1 |

| Monte Morello (n = 152) | ||||

| Gender (%) | ||||

| Male | 18.8 | 9.8 | 65.2 | 6.3 |

| Female | 12.5 | 20.0 | 65.0 | 2.5 |

| Age (%) | ||||

| Less than 20 years old | 28.6 | 0.0 | 71.4 | 0.0 |

| 21–30 years old | 10.4 | 24.1 | 58.6 | 6.9 |

| 31–40 years old | 18.3 | 13.2 | 60.5 | 7.9 |

| 41–50 years old | 13.7 | 13.6 | 63.6 | 9.1 |

| 51–60 years old | 16.1 | 9.7 | 74.2 | 0.0 |

| 61–70 years old | 33.2 | 5.6 | 55.6 | 5.6 |

| More than 70 years old | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| Level of education (%) | ||||

| Elementary/technical school degree | 27.3 | 0.0 | 72.7 | 0.0 |

| High school degree | 13.3 | 14.7 | 68.0 | 4.0 |

| University/post-university degree | 18.5 | 12.3 | 61.5 | 7.7 |

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics/Needs | Relaxing | Companionship | Sport | Activities with Pets | Contact with Nature | Therapeutic Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monte Marzola (n = 129) | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 4.40 ± 0.91 | 3.44 ± 1.51 | 4.54 ± 0.89 | 1.93 ± 1.45 | 4.38 ± 1.00 | 3.12 ± 1.78 |

| Female | 4.38 ± 0.82 | 3.76 ± 1.38 | 4.52 ± 0.77 | 2.65 ± 1.92 | 4.52 ± 0.95 | 3.82 ± 1.52 |

| Age | ||||||

| Less than 20 years old | 3.83 ± 1.33 | 4.00 ± 1.67 | 4.17 ± 1.17 | 2.60 ± 1.52 | 3.00 ± 1.41 | 2.75 ± 1.26 |

| 21–30 years old | 4.31 ± 0.87 | 3.44 ± 1.46 | 4.06 ± 1.00 | 2.40 ± 1.55 | 4.44 ± 0.81 | 3.69 ± 1.62 |

| 31–40 years old | 4.39 ± 0.78 | 3.19 ± 1.54 | 4.71 ± 0.55 | 1.57 ± 1.21 | 4.35 ± 1.07 | 2.68 ± 1.78 |

| 41–50 years old | 4.50 ± 0.79 | 3.73 ± 1.22 | 4.42 ± 1.02 | 2.31 ± 1.82 | 4.76 ± 0.44 | 3.40 ± 1.92 |

| 51–60 years old | 4.80 ± 0.52 | 3.70 ± 1.66 | 4.80 ± 0.70 | 2.00 ± 1.71 | 4.45 ± 1.05 | 3.37 ± 1.86 |

| 61–70 years old | 4.33 ± 0.71 | 3.25 ± 1.49 | 4.88 ± 0.35 | 2.50 ± 2.07 | 4.63 ± 0.74 | 4.00 ± 1.00 |

| More than 70 years old | 3.25 ± 1.71 | 4.25 ± 0.96 | 4.33 ± 1.11 | 3.33 ± 2.08 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | 4.75 ± 0.50 |

| Level of education | ||||||

| Elementary/technical school degree | 3.80 ± 1.26 | 3.86 ± 1.41 | 4.54 ± 0.88 | 3.08 ± 1.80 | 3.93 ± 1.28 | 3.92 ± 1.24 |

| High school degree | 4.46 ± 0.88 | 3.82 ± 1.49 | 4.36 ± 1.14 | 2.06 ± 1.65 | 4.65 ± 0.89 | 3.50 ± 1.79 |

| University/post-university degree | 4.54 ± 0.78 | 3.21 ± 1.48 | 4.66 ± 1.02 | 1.93 ± 1.69 | 4.42 ± 1.15 | 3.05 ± 1.72 |

| Total | 4.40 ± 0.88 | 3.54 ± 1.47 | 4.53 ± 0.85 | 2.15 ± 1.63 | 4.43 ± 0.98 | 3.34 ± 1.72 |

| Monte Morello (n = 152) | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 4.66 ± 0.56 | 4.21 ± 1.09 | 4.01 ± 1.24 | 1.96 ± 1.58 | 4.70 ± 0.68 | 4.21 ± 0.76 |

| Female | 4.65 ± 0.62 | 4.43 ± 0.98 | 3.60 ± 1.48 | 2.75 ± 1.77 | 4.65 ± 0.53 | 4.23 ± 0.73 |

| Age | ||||||

| Less than 20 years old | 4.29 ± 0.76 | 4.71 ± 0.49 | 4.43 ± 0.53 | 2.86 ± 1.68 | 4.71 ± 0.49 | 4.00 ± 0.82 |

| 21–30 years old | 4.72 ± 0.53 | 4.28 ± 1.07 | 3.72 ± 1.44 | 1.59 ± 1.40 | 4.69 ± 0.47 | 4.00 ± 0.60 |

| 31–40 years old | 4.76 ± 0.49 | 4.24 ± 1.20 | 4.03 ± 1.28 | 2.37 ± 1.68 | 4.58 ± 0.86 | 4.32 ± 0.62 |

| 41–50 years old | 4.68 ± 0.48 | 3.95 ± 1.05 | 4.14 ± 1.25 | 1.82 ± 1.56 | 4.82 ± 0.39 | 4.27 ± 0.88 |

| 51–60 years old | 4.65 ± 0.61 | 4.35 ± 0.70 | 3.97 ± 1.25 | 2.16 ± 1.61 | 4.71 ± 0.46 | 4.32 ± 0.83 |

| 61–70 years old | 4.50 ± 0.71 | 4.39 ± 0.76 | 3.22 ± 1.44 | 2.89 ± 2.00 | 4.67 ± 0.97 | 4.17 ± 0.86 |

| More than 70 years old | 4.57 ± 0.79 | 4.29 ± 0.53 | 4.14 ± 1.46 | 2.00 ± 1.73 | 4.71 ± 0.49 | 4.29 ± 0.95 |

| Level of education | ||||||

| Elementary/technical school degree | 4.33 ± 0.78 | 4.42 ± 1.00 | 4.33 ± 1.15 | 2.75 ± 2.01 | 4.42 ± 1.16 | 4.08 ± 1.00 |

| High school degree | 4.69 ± 0.54 | 4.15 ± 1.05 | 3.97 ± 1.23 | 2.16 ± 1.69 | 4.79 ± 0.44 | 4.29 ± 0.80 |

| University/post-university degree | 4.68 ± 0.56 | 4.38 ± 1.09 | 3.74 ± 1.43 | 2.06 ± 1.57 | 4.62 ± 0.70 | 4.15 ± 0.64 |

| Total | 4.66 ± 0.55 | 4.27 ± 1.06 | 3.90 ± 1.32 | 2.16 ± 1.67 | 4.68 ± 0.65 | 4.22 ± 0.75 |

| Socio-Demographic characteristics/Emotions | Restlessness | Familiarity | Physical Wellbeing | Harmony | Safety | Freedom | Isolation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monte Marzola (n = 129) | |||||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 1.12 ± 0.49 | 4.12 ± 1.05 | 4.61 ± 0.76 | 4.48 ± 0.75 | 4.16 ± 1.10 | 4.56 ± 0.80 | 2.69 ± 1.51 |

| Female | 1.10 ± 0.30 | 4.16 ± 1.14 | 4.63 ± 0.79 | 4.56 ± 0.80 | 4.00 ± 1.26 | 4.73 ± 0.60 | 2.78 ± 1.67 |

| Age | |||||||

| Less than 20 years old | 1.74 ± 1.14 | 3.60 ± 1.34 | 4.33 ± 0.87 | 4.33 ± 0.82 | 3.00 ± 0.63 | 4.67 ± 0.82 | 2.73 ± 1.72 |

| 21–30 years old | 1.03 ± 0.27 | 4.00 ± 0.85 | 4.50 ± 0.94 | 4.47 ± 0.92 | 3.93 ± 1.33 | 4.33 ± 0.90 | 2.64 ± 1.55 |

| 31–40 years old | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 3.54 ± 1.36 | 4.30 ± 1.62 | 4.27 ± 0.88 | 3.73 ± 1.32 | 4.36 ± 1.05 | 2.64 ± 1.39 |

| 41–50 years old | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 4.19 ± 0.85 | 4.74 ± 0.45 | 4.53 ± 0.70 | 4.65 ± 0.79 | 4.63 ± 0.60 | 2.90 ± 1.59 |

| 51–60 years old | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 4.57 ± 0.77 | 4.89 ± 0.47 | 4.72 ± 0.57 | 4.39 ± 1.04 | 4.89 ± 0.32 | 2.68 ± 1.76 |

| 61–70 years old | 1.02 ± 0.35 | 4.09 ± 1.14 | 4.80 ± 0.63 | 4.56 ± 0.73 | 4.22 ± 0.97 | 4.80 ± 0.42 | 2.25 ± 1.51 |

| More than 70 years old | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | 4.75 ± 0.50 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | 4.75 ± 0.50 | 3.40 ± 2.00 |

| Level of education | |||||||

| Elementary/technical school degree | 1.80 ± 1.03 | 3.62 ± 1.19 | 4.69 ± 0.63 | 4.57 ± 0.65 | 3.77 ± 1.09 | 4.79 ± 0.58 | 2.75 ± 1.76 |

| High school degree | 1.03 ± 0.18 | 4.24 ± 1.13 | 4.71 ± 0.71 | 4.62 ± 0.74 | 4.21 ± 0.96 | 4.66 ± 0.68 | 2.70 ± 1.51 |

| University/post-university degree | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 4.20 ± 0.97 | 4.52 ± 0.84 | 4.40 ± 0.81 | 4.14 ± 1.29 | 4.51 ± 0.84 | 2.72 ± 1.56 |

| Total | 1.11 ± 0.45 | 4.13 ± 1.07 | 4.62 ± 0.76 | 4.51 ± 0.76 | 4.11 ± 1.15 | 4.61 ± 0.75 | 2.72 ± 1.55 |

| Monte Morello (n = 152) | |||||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 1.44 ± 1.33 | 4.31 ± 1.10 | 4.57 ± 1.47 | 4.62 ± 0.69 | 3.63 ± 0.94 | 4.81 ± 0.41 | 2.76 ± 1.37 |

| Female | 1.50 ± 0.90 | 4.15 ± 0.95 | 4.50 ± 0.97 | 4.58 ± 0.87 | 3.75 ± 0.88 | 4.75 ± 0.63 | 2.98 ± 1.33 |

| Age | |||||||

| Less than 20 years old | 1.43 ± 0.53 | 4.14 ± 0.69 | 4.86 ± 0.38 | 4.57 ± 0.79 | 3.00 ± 1.00 | 4.86 ± 0.38 | 2.14 ± 1.21 |

| 21–30 years old | 1.48 ± 0.69 | 3.69 ± 1.20 | 4.48 ± 0.74 | 4.66 ± 0.48 | 3.83 ± 0.76 | 4.93 ± 0.26 | 3.10 ± 1.45 |

| 31–40 years old | 1.58 ± 0.86 | 4.21 ± 1.04 | 4.50 ± 0.76 | 4.71 ± 0.52 | 3.58 ± 0.76 | 4.68 ± 0.53 | 2.76 ± 1.26 |

| 41–50 years old | 1.55 ± 0.74 | 4.36 ± 0.79 | 4.82 ± 0.50 | 4.45 ± 0.67 | 3.50 ± 0.96 | 4.86 ± 0.35 | 2.36 ± 1.36 |

| 51–60 years old | 1.32 ± 0.54 | 4.61 ± 0.56 | 4.48 ± 0.85 | 4.52 ± 0.68 | 3.74 ± 0.68 | 4.77 ± 0.62 | 2.84 ± 1.27 |

| 61–70 years old | 1.39 ± 0.61 | 4.56 ± 0.62 | 4.33 ± 0.91 | 4.56 ± 0.51 | 3.89 ± 1.13 | 4.78 ± 0.43 | 2.83 ± 1.58 |

| More than 70 years old | 1.14 ± 0.38 | 4.57 ± 0.79 | 4.86 ± 0.38 | 4.86 ± 0.38 | 3.57 ± 0.98 | 4.71 ± 0.76 | 3.86 ± 0.90 |

| Level of education | |||||||

| Elementary/technical school degree | 1.50 ± 0.67 | 4.50 ± 0.52 | 4.75 ± 0.45 | 4.50 ± 0.67 | 3.58 ± 0.79 | 4.92 ± 0.29 | 2.83 ± 1.53 |

| High school degree | 1.39 ± 0.63 | 4.44 ± 0.79 | 4.63 ± 0.73 | 4.56 ± 0.60 | 3.64 ± 0.97 | 4.79 ± 0.53 | 2.97 ± 1.38 |

| University/post-university degree | 1.52 ± 0.75 | 4.03 ± 1.09 | 4.43 ± 0.79 | 4.68 ± 0.53 | 3.69 ± 0.73 | 4.78 ± 0.45 | 2.63 ± 1.29 |

| Total | 1.45 ± 0.69 | 4.27 ± 0.93 | 4.55 ± 0.74 | 4.61 ± 0.58 | 3.66 ± 0.85 | 4.80 ± 0.48 | 2.82 ± 1.36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Meo, I.; Alfano, A.; Cantiani, M.G.; Paletto, A. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Citizens’ Attitudes and Behaviors in the Use of Peri-Urban Forests: An Experience from Italy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042852

De Meo I, Alfano A, Cantiani MG, Paletto A. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Citizens’ Attitudes and Behaviors in the Use of Peri-Urban Forests: An Experience from Italy. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042852

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Meo, Isabella, Andrea Alfano, Maria Giulia Cantiani, and Alessandro Paletto. 2023. "The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Citizens’ Attitudes and Behaviors in the Use of Peri-Urban Forests: An Experience from Italy" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042852

APA StyleDe Meo, I., Alfano, A., Cantiani, M. G., & Paletto, A. (2023). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Citizens’ Attitudes and Behaviors in the Use of Peri-Urban Forests: An Experience from Italy. Sustainability, 15(4), 2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042852