The Effects of Principals’ Instructional Leadership on Primary School Students’ Academic Achievement in China: Evidence from Serial Multiple Mediating Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Literature on the Indirect Effect of PIL on SAA

2.1.1. Effective Professional Development for Teachers as a Mediator

2.1.2. Teaching Strategies as a Mediator

2.2. Literature on the Serial Multiple Mediating Effects between PIL and SAA

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Procedure and Participants

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Tests of Students’ Academic Achievement

3.2.2. The Principals’ Instructional Leadership Scale

3.2.3. The Teachers’ Professional Development Scale

3.2.4. The Teaching Strategy Scale

3.3. Analytic Approaches

3.3.1. Value-Added Model (VAM)

3.3.2. Structural Equation Model (SEM)

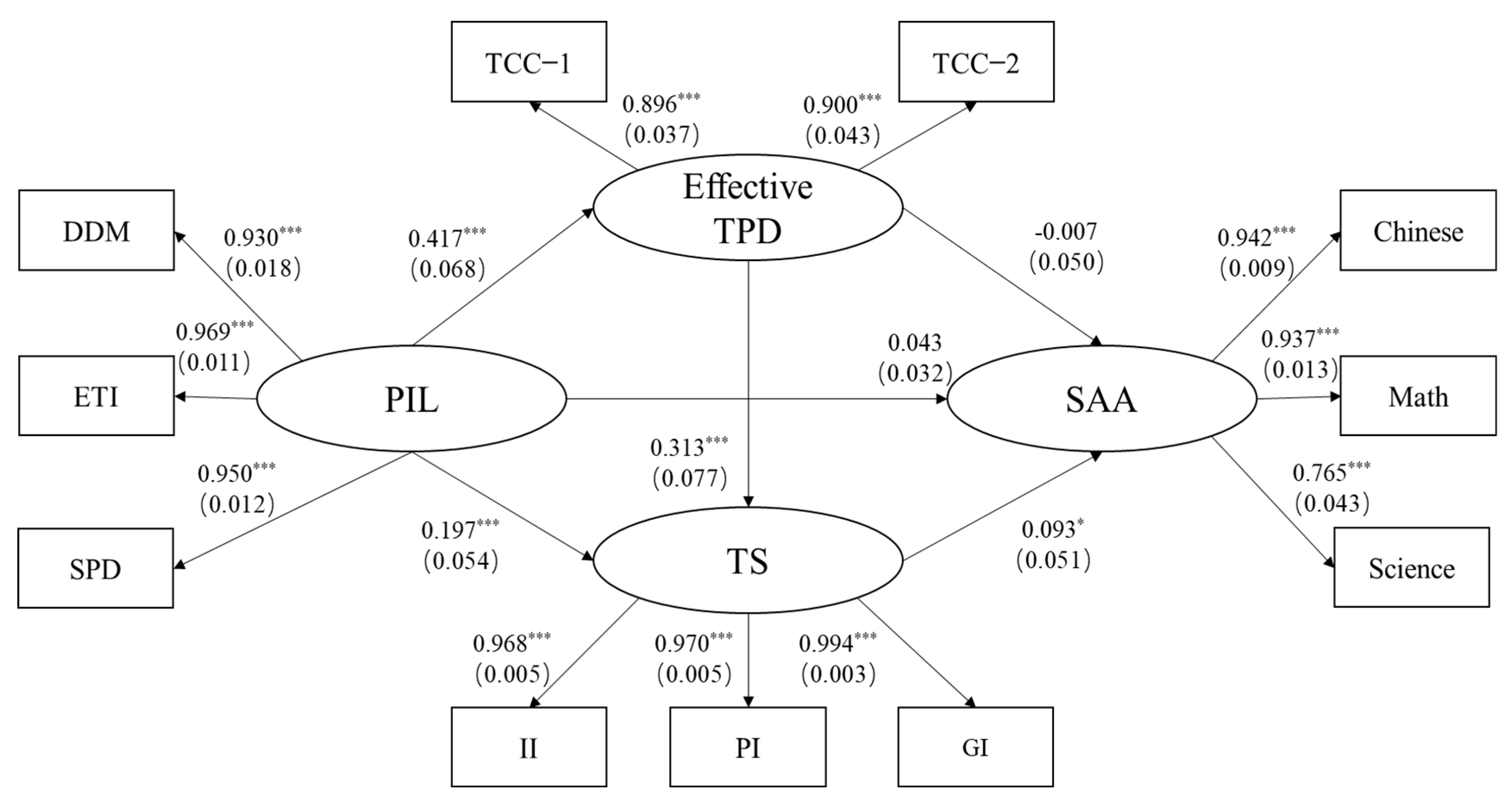

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. The Effects of TPD of Chinese Primary Schools on SAA

4.3. The Effect Paths of PIL of Chinese Primary Schools on SAA

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dimension | Item | Factor Loading |

| Democratic Decision-Making (DDM) | Treat every teacher fairly in regard to teaching evaluation. | 0.939 *** |

| Provide opportunities for teachers to participate in teaching reform. | 0.946 *** | |

| Ask for advice from teachers on teaching management. | 0.959 *** | |

| Make educational administration information public. | 0.930 *** | |

| Make teaching management information public. | 0.925 *** | |

| Encouraging Teaching Innovation (ETI) | Encourage teachers to try new teaching methods and use them in practice. | 0.974 *** |

| Respect and support teachers’ teaching innovation. | 0.976 *** | |

| Encourage teachers to attach importance to the learning and communication of new knowledge. | 0.942 *** | |

| Encourage teaching and research group teachers to learn from each other about new teaching methods or knowledge. | 0.895 *** | |

| Supporting Teachers’ Professional Development (SPD) | Encourage teachers to participate in teaching and training activities. | 0.947 *** |

| Provide abundant social resources for teaching. | 0.923 *** | |

| Inquire about teachers’ needs for further education and provide information, materials and channels. | 0.914 *** |

Appendix B

| Dimension | Item | Factor Loading |

| Professional Guidance or Innovation (PGI) | Attend experts’ lectures. | 0.493 *** |

| Participate in project research. | 0.413 *** | |

| Participate in the teaching and research activities organized by the school or other departments. | 0.946 *** | |

| Teacher Cooperation and Communication (TCC) | Attend others’ lectures and discuss with colleagues after class. | 0.895 *** |

| Share teaching experiences and discuss problems with colleagues. | 0.897 *** | |

| Prepare and evaluate lessons collectively with the teaching and research group. | 0.871 *** | |

| Individual Teaching Reflection (ITR) | Analyze the teaching cases by myself. | 0.881 *** |

| Obtain teaching knowledge or reflect on teaching problems on my own. | 0.876 *** |

Appendix C

| Dimension | Item | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|

| Individualized Instruction (II) | Teachers encourage us to use different ways to learn. | 0.957 *** |

| Teachers know our strengths and weakness. | 0.950 *** | |

| Teachers provide us with individual advice for learning. | 0.948 *** | |

| Teachers assign individualized tasks to us. | 0.782 *** | |

| Teachers pay attention to our individual progress. | 0.866 *** | |

| Participatory Instruction (PI) | Teachers organize group discussions in the class. | 0.884 *** |

| Teachers make the class interesting. | 0.938 *** | |

| Teachers share their feelings with us. | 0.961 *** | |

| Guided Inquiry (GI) | Teachers guide us in discussions. | 0.966 *** |

| Teachers make connections between the content knowledge and our daily lives. | 0.973 *** | |

| Teachers encourage us to make a hypothesis and test it with various methods. | 0.988 *** | |

| Teachers encourage us to express our own opinions. | 0.968 *** | |

| Teachers encourage us to use different methods to solve a problem. | 0.968 *** |

References

- Johnson, B. Teacher collaboration: Good for some, not so good for others. Educ. Stud. 2010, 29, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scribner, S.M.P.; Crow, G.M.; López, G.R.; Murtadha, K. “Successful” principals: A contested notion for superintendents and principals. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2011, 21, 390–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P.; Gümü, S.; Belliba, M.S. “Are principals instructional leaders yet?”: A science map of the knowledge base on instructional leadership, 1940–2018. Scientometrics 2020, 122, 1629–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. Leadership for learning: Lessons from 40 years of empirical research. J. Educ. Adm. 2011, 49, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Patten, S.; Jantzi, D. Testing a conception of how school leadership influences student learning. Educ. Adm. Q. 2010, 46, 671–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, V.M.J.; Lloyd, C.A.; Rowe, K.J. The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educ. Adm. Q. 2008, 44, 635–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. Instructional leadership and the school principal: A passing fancy that refuses to fade away. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2005, 4, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, J.A.; Loeb, S.; Master, B. Effective instructional time use for school leaders: Longitudinal evidence from observations of principals. Educ. Res. 2013, 42, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.H.; Slater, C.L.; Backhoff, E. Principal perceptions and student achievement in reading in Korea, Mexico, and the United States educational leadership, school autonomy, and use of test results. Educ. Adm. Q. 2013, 49, 489–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y. The Correlativity Analysis of Principal’s Curriculum Leadership and the Effectiveness of the Promotion of Teaching. Master’s Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 1 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinger, P. Bringing context out of the shadows of leadership. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2018, 46, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Yu, S.; Zhang, L. A review of research on professional learning communities in mainland China (2006–2015): Key findings and emerging themes. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2018, 46, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Nyeu, F.Y.; Chen, J.S. Principal instructional leadership in Taiwan: Lessons from two decades of research. J. Educ. Adm. 2015, 53, 492–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, T.; Glover, D. School leadership models: What do we know? Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2014, 34, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. A review of three decades of doctoral studies using the principal instructional management rating scale: A lens on methodological progress in educational leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 2011, 47, 271–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, D.; Devos, G.; Valcke, M. The relationships between school autonomy gap, principal leadership, teachers’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2016, 45, 959–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witziers, B.; Bosker, R.J.; Krüger, M.L. Educational leadership and student achievement: The elusive search for an association. Educ. Adm. Q. 2003, 39, 398–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, D. Impact of instructional leadership on high school student academic achievement in China. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2019, 20, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossert, S.T.; Dwyer, D.C.; Rowan, B.; Lee, G.V. The instructional management role of the principal. Educ. Adm. Q. 1982, 18, 34–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, T. Instructional leadership in centralised contexts: Constrained by limited powers. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2020, 48, 593–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, E.; Loeb, S. New thinking about instructional leadership. Phi Delta Kappan 2010, 92, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, H.M.; Printy, S.M. Principal leadership and school performance: An integration of transformational and instructional leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 2003, 39, 370–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Z.; Yin, H.B.; Huang, S.H. Teacher participation in school-based professional development in China: Does it matter for teacher efficacy and teaching strategies? Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2019, 25, 821–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Kong, L. An exploration of reasons for Shanghai’s success in the OECD Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2009. Front. Educ. China 2012, 7, 124–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.L.N. How has recent curriculum reform in China influenced school-based teacher learning? an ethnographic study of two subject departments in Shanghai, China. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 40, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.L.N.; Tsui, A. How do teachers view the effects of school-based in-service learning activities? A case study in China. J. Educ. Teach. 2007, 33, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, N. How to improve teachers’ instructional practices: The role of professional learning activities, classroom observation and leadership content knowledge in Turkey. J. Educ. Adm. 2020, 58, 585–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, N. Principal leadership and students’ achievement: Mediated pathways of professional community and teachers’ instructional practices. KEDI J. Educ. Policy 2019, 16, 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian, J.; Huang, H.; Allensworth, E. Examining integrated leadership systems in high schools: Connecting principal and teacher leadership to organizational processes and student outcomes. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2017, 28, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babinski, L.M.; Amendum, S.J.; Knotek, S.E.; Sánchez, M.; Malone, P. Improving young English learners’ language and literacy skills through teacher professional development: A randomized controlled trial. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2018, 55, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, S.; Yurtseven, N. Professional learning as a predictor for instructional quality: A secondary analysis of TALIS. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2018, 29, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basma, B.; Savage, R. Teacher professional development and student literacy growth: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 30, 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, R.; Hill, H.; Corey, D. The impact of a professional development program on teachers’ mathematical knowledge for teaching, instruction, and student achievement. J. Res. Educ. Eff. 2017, 10, 379–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, H.C. Fixing teacher professional development. Phi Delta Kappan 2009, 90, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M.; McMaster, P. Sources of self-efficacy: Four professional development formats and their relationships to self-efficacy and implementation of new teaching strategies. Elem. Sch. J. 2009, 110, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, B.A.; Lefgren, L. The impact of teacher training on student achievement quasi-experimental evidence from school reform efforts in Chicago. J. Hum. Resour. 2004, 39, 50–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D.N.; Sass, T.R. Teacher training, teacher quality and student achievement. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 798–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Hallinger, P. Principal instructional leadership, teacher self-efficacy, and teacher professional learning in China: Testing a mediated-effects model. Educ. Adm. Q. 2018, 54, 501–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Huang, Y.T.; Huang, L. Effects of school organizational conditions on teacher professional learning in China: The mediating role of teacher self-efficacy. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2020, 66, 100893. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.H.; Lee, I.H.; Cooc, N. The role of school-level mechanisms: How principal support, professional learning communities, collective responsibility, and group-level teacher expectations affect student achievement. Educ. Adm. Q. 2019, 55, 742–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Hu, Y. The impact of principal’s leadership on teacher collaboration in primary and secondary schools. J. Educ. Sci. Hunan Norm. Univ. 2019, 5, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Vanblaere, B.; Devos, G. Relating school leadership to perceived professional learning community characteristics: A multilevel analysis. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 57, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Guo, W. Emotional intelligence can make a difference: The impact of principals’ emotional intelligence on teaching strategy mediated by instructional leadership. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2020, 48, 82–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.C.; Yang, F.; Xu, Q.Y. Principals’ teaching leadership and analysis of its affecting mechanism: Research of the correlation between principals’ teaching leadership and the school’s teaching quality. J. Soochow Univ. Educ. Sci. Ed. 2018, 6, 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- Bellibaş, M.Ş.; Polatcan, M.; Kılınç, A.Ç. Linking instructional leadership to teacher practices: The mediating effect of shared practice and agency in learning effectiveness. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2020, 50, 812–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, A.; Böhnke, A.; Thiel, F. Improving instructional competencies through individualized staff development and teacher collaboration in German schools. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2020, 34, 1289–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admiraal, W.; Kruiter, J.; Lockhorst, D.; Schenke, W.; Sligte, H.; Smit, B.; De Wit, W. Affordances of teacher professional learning in secondary schools. Stud. Contin. Educ. 2016, 38, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.Y.; Wo, J.Z. The structure of primary school Chinese teachers’ teaching strategies. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2000, 16, 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D.B.; Stuart, E.A.; Zanutto, E.L. A potential outcomes view of value-added assessment in education. J. Educ. Behav. Stats 2004, 29, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanushek, E.A. The impact of differential expenditures on school performance. Educ. Res. 1989, 18, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonen, T.; Damme, J.V.; Onghena, P. Teacher effects on student achievement in first grade: Which aspects matter most? Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2014, 25, 126–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F.; Sadoulet, E.; De Janvry, A. The contributions of school quality and teacher qualifications to student performance: Evidence from a natural experiment in Beijing middle schools. J. Hum. Resour. 2011, 46, 123–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, A. Experimental estimates of education production functions. Q. J. Econ. 1999, 114, 497–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu, N. School resources and student achievement: A study of primary schools in Zimbabwe. Educ. Res. Rev. 2018, 13, 236–248. [Google Scholar]

- Desimone, L.M. Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educ. Res. 2009, 38, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Testing Structural Equation Models; Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakides, L.; Creemers, B.P.; Antoniou, P. Teacher behaviour and student outcomes: Suggestions for research on teacher training and professional development. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2009, 25, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hallinger, P.; Ko, J. Principal leadership and school capacity effects on teacher learning in Hong Kong. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2016, 30, 76–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrieken, K.; Dochy, F.; Raes, E.; Kyndt, E. Teacher collaboration: A systematic Review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 15, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, L.M.; Pak, K. Instructional coaching as high-quality professional development. Theory Pract. 2017, 56, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strain, M. Review symposium on “Changing Teachers, Changing Times: Teachers’ Work and Culture in the Postmodern Age” by Andy Hargreaves. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 1994, 22, 270–272. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.L.; Elchert, D.; Asikin-Garmager, A. Comparing the effects of teacher collaboration on student performance in Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2018, 50, 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, T. Principal instructional leadership for teacher participation in professional development: Evidence from Japan, Singapore, and South Korea. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2020, 21, 261–278. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Lee, J.; Heo, S.; Park, S.; Han, S.; Han, E. The qualitative meta analysis of attributes in teacher learning community. Korean J. Educ. Res. 2015, 53, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.P.; Wang, C.; Hu, Y.M. How to improve students’ academic performance: A perspective of learning and teaching strategies. J. East China Norm. Univ. Educ. Sci. 2020, 38, 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Chu, H.Q. Transforming teaching models: Reflections on PISA2018. Educ. Res. 2019, 40, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Mean | SD | Max | Min | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students’ Academic Achievement (SAA) in 2017 | 500.000 | 92.760 | 786.720 | 307.000 | 277 |

| Democratic Decision-Making (DMM) | 4.333 | 0.485 | 5.000 | 2.667 | 277 |

| Encouraging Teaching Innovation (ETI) | 4.488 | 0.398 | 5.000 | 3.063 | 277 |

| Supporting TPD (SPD) | 4.347 | 0.467 | 5.000 | 2.733 | 277 |

| Professional Guidance or Innovation (PGI) | 2.904 | 0.484 | 4.667 | 1.000 | 277 |

| Teacher Cooperation and Communication (TCC) | 4.145 | 0.567 | 5.000 | 2.000 | 277 |

| Individual Teaching Reflection (ITR) | 4.147 | 0.565 | 5.000 | 2.167 | 277 |

| Individualized Instruction (II) | 3.632 | 0.356 | 4.779 | 2.864 | 277 |

| Participatory Instruction (PI) | 3.594 | 0.401 | 4.892 | 2.667 | 277 |

| Guided Inquiry (GI) | 3.781 | 0.376 | 4.921 | 2.771 | 277 |

| SAA in 2016 | 500.000 | 93.596 | 753.919 | 251.400 | 264 |

| Student–Teacher Ratio | 20.725 | 5.866 | 40.875 | 1.000 | 243 |

| Average SES | −0.151 | 0.403 | 0.916 | −1.101 | 277 |

| Proportion of Teachers with a Bachelor’s Degree | 0.815 | 0.185 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 277 |

| Average Teaching Years | 10.897 | 4.312 | 20.000 | 1.500 | 277 |

| Average Working Hours | 8.681 | 0.940 | 12.375 | 6.000 | 277 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGI | 0.021 | ||||||||||

| (6.056) | |||||||||||

| TCC | 0.060 * | ||||||||||

| (5.334) | |||||||||||

| ITR | 0.038 | ||||||||||

| (5.344) | |||||||||||

| PGI-1 | 0.0004 | ||||||||||

| (5.330) | |||||||||||

| PGI-2 | −0.001 | ||||||||||

| (4.888) | |||||||||||

| PGI-3 | 0.047 | ||||||||||

| (4.405) | |||||||||||

| TCC-1 | 0.055 * | ||||||||||

| (4.444) | |||||||||||

| TCC-2 | 0.054 * | ||||||||||

| (5.434) | |||||||||||

| TCC-3 | 0.055 | ||||||||||

| (4.899) | |||||||||||

| ITR-1 | 0.039 | ||||||||||

| (4.584) | |||||||||||

| ITR-2 | 0.031 | ||||||||||

| (5.504) | |||||||||||

| Control Variables 1 | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| F | 114.02 *** | 115.92 *** | 114.61 *** | 113.73 *** | 113.73 *** | 115.19 *** | 115.71 *** | 115.51 *** | 115.45 *** | 114.64 *** | 114.34 *** |

| N | 231 | 231 | 231 | 231 | 231 | 231 | 231 | 231 | 231 | 231 | 231 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.797 | 0.800 | 0.798 | 0.797 | 0.797 | 0.799 | 0.800 | 0.799 | 0.799 | 0.798 | 0.798 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Chan, P.W.K.; Hu, Y. The Effects of Principals’ Instructional Leadership on Primary School Students’ Academic Achievement in China: Evidence from Serial Multiple Mediating Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2844. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032844

Li J, Chan PWK, Hu Y. The Effects of Principals’ Instructional Leadership on Primary School Students’ Academic Achievement in China: Evidence from Serial Multiple Mediating Analysis. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2844. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032844

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jiazhe, Philip Wing Keung Chan, and Yongmei Hu. 2023. "The Effects of Principals’ Instructional Leadership on Primary School Students’ Academic Achievement in China: Evidence from Serial Multiple Mediating Analysis" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2844. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032844

APA StyleLi, J., Chan, P. W. K., & Hu, Y. (2023). The Effects of Principals’ Instructional Leadership on Primary School Students’ Academic Achievement in China: Evidence from Serial Multiple Mediating Analysis. Sustainability, 15(3), 2844. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032844