The Influence of Psychological Capital on Individual’s Social Responsibility through the Pivotal Role of Psychological Empowerment: A Study Towards a Sustainable Workplace Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

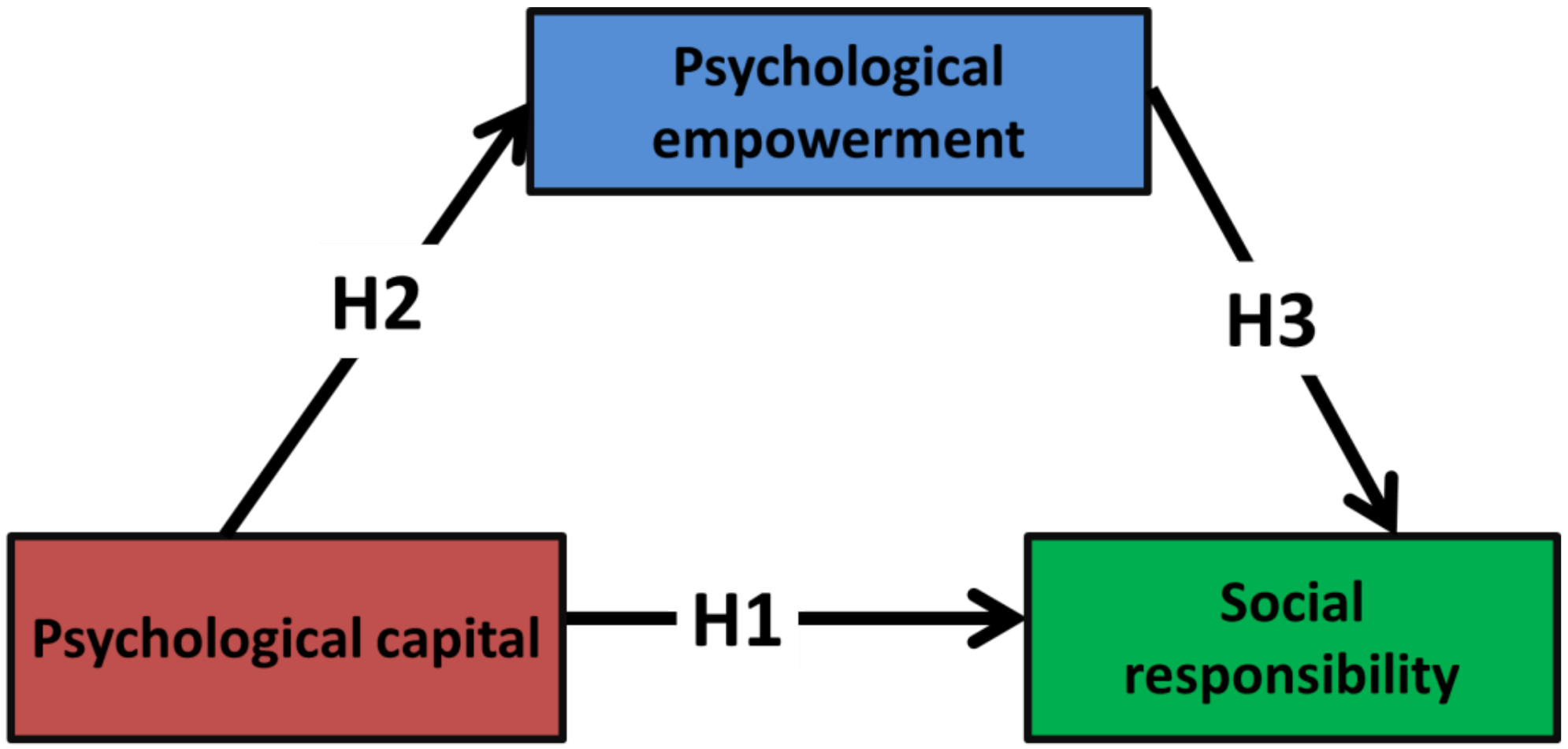

Theory and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Population

2.2. Sample Size and Sampling Technique

2.3. Selection Criteria and Study Period

2.4. Data Collection and Tools

2.5. Pilot Study

2.6. Data Analysis and Path Analysis

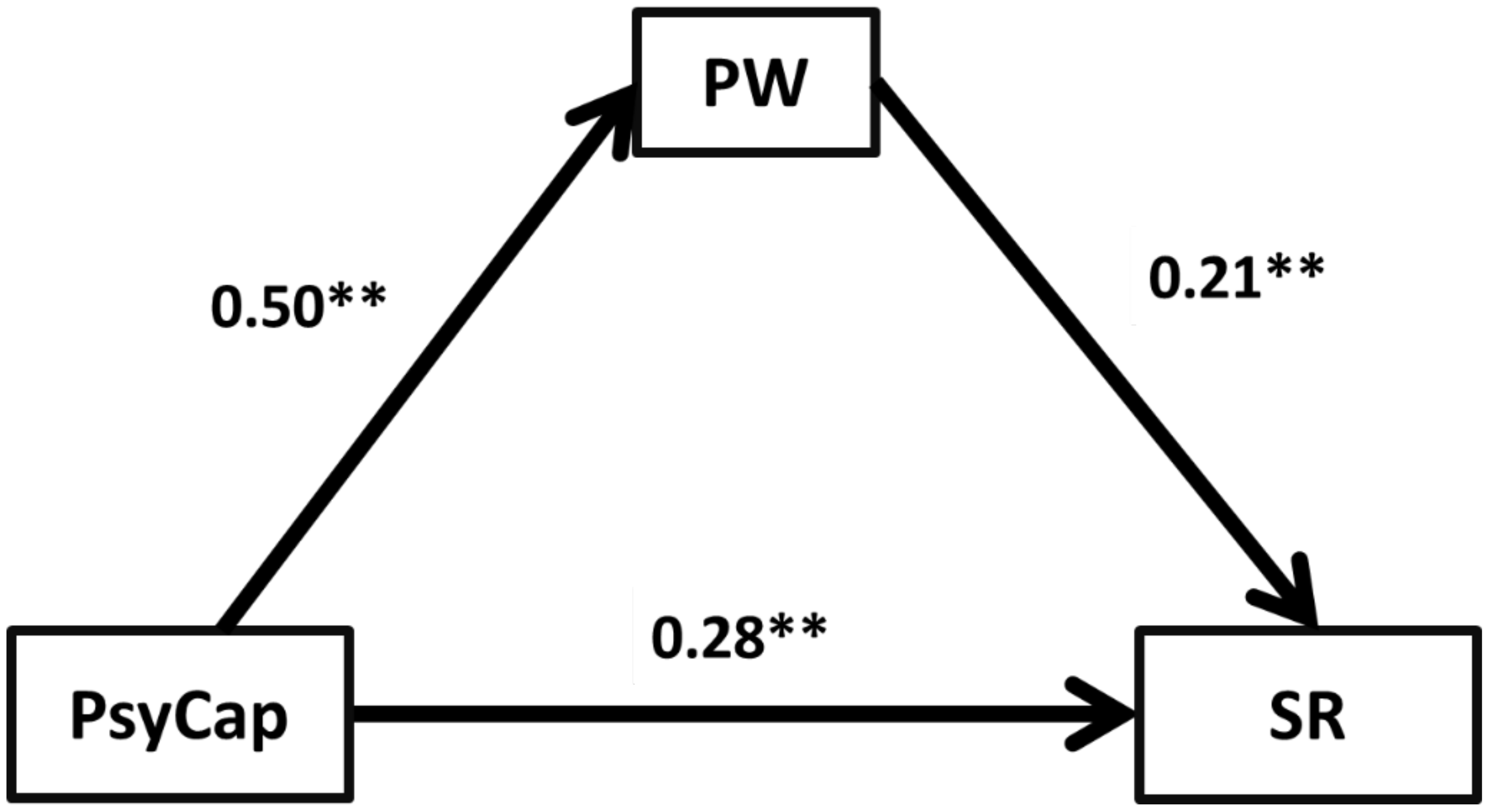

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khusanova, R.; Choi, S.B.; Kang, S.-W. Sustainable Workplace: The Moderating Role of Office Design on the Relationship between Psychological Empowerment and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour in Uzbekistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H.R. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman; University of Iowa Press: Iowa City, IA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N. Corporate Social Responsibility: An analysis of impact and challenges in India. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Manag. Entrep. (IJSSME) 2019, 3, 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bénabou, R.; Tirole, J. Individual and corporate social responsibility. Economica 2010, 77, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droms Hatch, C.; Stephen, S.-A. Gender effects on perceptions of individual and corporate social responsibility. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. 2015, 17, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Takala, T.; Pallab, P. Individual, Collective and Social Responsibility of the Firm. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2000, 9, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.L.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.A. Psychological Capital Questionnaire. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037/t06483-000 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Avey, J.; Luthans, F.; Youssef, C. The additive value of positive psychological capital in predicting work attitudes and behaviors. J. Manag. 2012, 30, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuscheler, D.; Engelen, A.; Zahra, S.A. The role of top management teams in transforming technology-based new ventures’ product introductions into growth. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, A.H.; Veum, J.R.; Darity, W., Jr. The impact of psychological and human capital on wages. Econ. Inq. 1997, 35, 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Kerdawy, M.M.A. The role of corporate support for employee volunteering in strengthening the impact of green human resource management practices on corporate social responsibility in the Egyptian firms. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2019, 16, 1079–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.H.; Yoon, S.W.; Chae, C. Building social capital and learning relationships through knowledge sharing: A social network approach of management students’ cases. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 921–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological Capital and Beyond; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, S.-H.; Hu, D.-C.; Chung, Y.-C.; Chen, L.-W. LMX and employee satisfaction: Mediating effect of psychological capital. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmieleski, K.M.; Carr, J.C.; Baron, R.A. Integrating discovery and creation perspectives of entrepreneurial action: The relative roles of founding CEO human capital, social capital, and psychological capital in contexts of risk versus uncertainty. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2015, 9, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, F. Correlation between Psychological Capital and Occupational Burnout in Nurses. Health Educ. Health Promot. 2018, 6, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A.; Shahnwaz, M.G.; Imran, M.; Rehman, U.; Kamra, A.; Osmany, M. Revisiting and Expanding Psychological Capital: Implications for Counterproductive Work Behaviour. Trends Psychol. 2022, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zeer, I.; Alkhatib, A.A.; Alshrouf, M. Determinants of organisational commitment of universities’ employees. Int. J. Acad. Res. Account. Financ. Manag. Sci. 2019, 9, 136–141. [Google Scholar]

- Dust, S.B.; Resick, C.J.; Mawritz, M.B. Transformational leadership, psychological empowerment, and the moderating role of mechanistic–organic contexts. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 413–433. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F.; Avey, J.B.; Avolio, B.J.; Peterson, S.J. The development and resulting performance impact of positive psychological capital. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2010, 21, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgens-Ekermans, G.; Herbert, M. Psychological capital: Internal and external validity of the Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PCQ-24) on a South African sample. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2013, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.F.; Wang, K.F.; Cross, W.; Lam, L.; Plummer, V.; Li, J. Quality of life in cancer patients with different preferences for nurse spiritual therapeutics: The role of psychological capital. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwakwe, R.C.; Okolie, U.C.; Ehiobuche, C.; Ochinanwata, C.; Idike, I.M. A Multi-Group Study of Psychological Capital and Job Search Behaviours Among University Graduates with and Without Work Placement Learning Experience. J. Career Assess. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikus, K.; Teoh, K.R. Psychological Capital, future-oriented coping, and the well-being of secondary school teachers in Germany. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 42, 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, D.; Tsai, C.-H.; Wang, C. The role of psychological capital in employee creativity. Career Dev. Int. 2019, 24, 420–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.S.; Neto, M.T.R.; Verwaal, E. Does cultural capital matter for individual job performance? A large-scale survey of the impact of cultural, social and psychological capital on individual performance in Brazil. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2018, 67, 1352–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, H.; Parker, A.; Roberts, W. Community sport programmes and social inclusion: What role for positive psychological capital? In The Potential of Community Sport for Social Inclusion; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-L.; Yang, D.-J. Potential contributions of psychological capital to the research field of marketing. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, F.; Tagharrobi, Z.; Sharifi, K.; Sooki, Z. Effects of happiness on psychological capital in middle-aged women: A randomized controlled trial. Int. Arch. Health Sci. 2021, 8, 253. [Google Scholar]

- Akbar, E.; Samira, T.; Mehdi, A. The relationship between psychological capital and organizational commitment. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 5057–5060. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Xie, Y. Authentic leadership and employees’ emotional labour in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 797–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Sousa, F.; Marques, C.; Pina e Cunha, M. Authentic leadership promoting employees’ psychological capital and creativity. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Ucbasaran, D.; Zhu, F.; Hirst, G. Psychological capital: A review and synthesis. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, S120–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef-Morgan, C.M.; Luthans, F. Psychological capital and well-being. Stress Health J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress 2015, 31, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.; Mourgan, F.H.A.; Al Kharusi, B.; Elfitori, C.M. Impact of entrepreneurial education, trait competitiveness and psychological capital on entrepreneurial behavior of university students in GCC. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.; Roche, M. Contribution of psychological capital to entrepreneurs success during recessionary times. In Proceedings of the SHAKE-UP: New Perspectives in Business Research and Education: New Zealand Applied Business Education Conference (NZABE) 2010, Napier, New Zealand, 27–28 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Social structural characteristics of psychological empowerment. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stander, M.W.; Rothmann, S. Psychological empowerment, job insecurity and employee engagement. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2010, 36, a849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewettinck, K.; Van Ameijde, M. Linking leadership empowerment behaviour to employee attitudes and behavioural intentions: Testing the mediating role of psychological empowerment. Pers. Rev. 2011, 40, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Chen, J. How does psychological empowerment prevent emotional exhaustion? psychological safety and organizational embeddedness as mediators. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 546687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Nix, G.; Hamm, D. Testing models of the experience of self-determination in intrinsic motivation and the conundrum of choice. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 95, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Núñez, M.I.; Rubio-Valdehita, S.; Diaz-Ramiro, E.M.; Aparicio-García, M.E. Psychological capital, workload, and burnout: What’s new? the impact of personal accomplishment to promote sustainable working conditions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppong Asante, K.; Meyer-Weitz, A.; Okafo, D.C. Psychological capital and orientation to happiness as protective factors for coping among first year university students in South Africa. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2022, 60, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, F.O.; Onyishi, I.E.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, A.M. Linking organizational trust with employee engagement: The role of psychological empowerment. Pers. Rev. 2014, 43, 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, T.A.; Khattak, M.N.; Zolin, R.; Shah, S.Z.A. Psychological empowerment and employee attitudinal outcomes: The pivotal role of psychological capital. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 42, 797–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanshenas, M.; Mirzaei, M. Leadership integrity and employees’ success: Role of ethical leadership, psychological capital, and psychological empowerment. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji, L.; Valizadeh, N.; Karimi, H. The effects of psychological capital and empowerment on entrepreneurial spirit: The case of Naghadeh County, Iran. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 27, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, H.; Fuciu, M.; Croitor, N. Research on Corporate Social Responsibility in the Development Region Centre in Romania. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 16, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Benson, J. When CSR is a social norm: How socially responsible human resource management affects employee work behavior. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1723–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Shao, R.; Skarlicki, D.P.; Paddock, E.L.; Kim, T.Y.; Nadisic, T. Corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: The moderating role of CSR-specific relative autonomy and individualism. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 559–579. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.-F.; Khuangga, D.L. Configurational paths of employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyuur, R.B.; Ofori, D.F.; Amankwah, M.O.; Baffoe, K.A. Corporate social responsibility and employee attitudes: The moderating role of employee age. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2022, 31, 100–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, R.V.; Memili, E.; Koç, B.; Young, S.L.; Yildirim-Öktem, Ö.; Sönmez, S. Innovativeness and corporate social responsibility in hospitality and tourism family firms: The role of family firm psychological capital. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 101, 103128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Sohail, M.S.; Jumaan, I.A.M. CSR perceptions and career satisfaction: The role of psychological capital and moral identity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacharalampous, N.; Papadimitriou, D. Perceived corporate social responsibility and affective commitment: The mediating role of psychological capital and the impact of employee participation. Human Resour. Dev. Q. 2021, 32, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B.; Norman, S.M. Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Luthans, F.; Jensen, S.M. Psychological capital: A positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Human Resour. Manag. 2009, 48, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravinder, E.B.; Saraswathi, A. Literature Review of Cronbach alpha coefficient (A) And Mcdonald’s Omega Coefficient (Ω). Eur. J. Mol. Clin. Med. 2020, 7, 2943–2949. [Google Scholar]

- Juhdi, H. Psychological capital and entrepreneurial success: A multiple-mediated relationship. Eur. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2015, 1, 110–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanjari, L. Investigating the relationship between social responsibility and improving organizational commitment in employees of Tehran Ghavamin Bank with respect to the mediating role of psychological empowerment. J. Fundam. Appl. Sci. 2017, 9, 96–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; He, J.; Morrison, A.M.; Andres Coca-Stefaniak, J. Effects of tourism CSR on employee psychological capital in the COVID-19 crisis: From the perspective of conservation of resources theory. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2716–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | Domains | No of Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Psychological capital | Hope, resilience, optimism, and self-efficacy | 15 |

| Psychological empowerment | Meaningfulness, self-determination, impact, and competence | 12 |

| Individual’s social responsibility | One domain | 20 |

| Variables | Categories | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 322 | 39.6 |

| Female | 491 | 60.4 | |

| Marital | Single | 209 | 25.7 |

| Married | 559 | 68.8 | |

| Divorced | 36 | 4.4 | |

| Widow | 9 | 1.1 | |

| Shift | Day Shift | 556 | 68.4 |

| Night Shift | 88 | 10.8 | |

| Day/Night | 169 | 20.8 | |

| Sector | Government | 579 | 71.2 |

| Private | 158 | 19.4 | |

| Own Business | 76 | 9.3 | |

| Total | 813 | 100 |

| Variable | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological capital | 1 | 5 | 4.06 | 0.58 | 0.910 |

| Hope | 1 | 5 | 4.03 | 0.66 | 0.845 |

| Resilience | 1 | 5 | 4.04 | 0.72 | 0.785 |

| Optimism | 1 | 5 | 4.09 | 0.73 | 0.755 |

| Self-efficacy | 1 | 5 | 4.12 | 0.72 | 0.743 |

| Psychological empowerment | 1 | 5 | 4.32 | 0.56 | 0.904 |

| Self-determination | 1 | 5 | 4.11 | 0.68 | 0.836 |

| Competence | 1 | 5 | 3.95 | 0.78 | 0.887 |

| Impact | 1 | 5 | 4.04 | 0.72 | 0.812 |

| Meaning | 1 | 5 | 4.39 | 0.72 | 0.845 |

| Social responsibility | 1 | 5 | 4.50 | 0.54 | 0.929 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social responsibility (SR) | 1 | ||

| 2. Psychological capital (PsyCap) | 0.417 ** | 1 | |

| 3. Psychological empowerment (PE) | 0.380 ** | 0.517 ** | 1 |

| Structural Paths | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects (95% CI) | Total Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| PsyCap → SR | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.39 |

| PE → SR | 0.21 | – | 0.21 |

| PsyCap → PE | 0.50 | – | 0.50 |

| Indices | Abbreviation | Value | Reference Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative chi-square | CMIN/df | 3.28 | ≥2.0 |

| Comparative fit index | CFI | 0.96 | ≥0.90 |

| Goodness of fit index | GFI | 0.95 | ≥0.90 |

| Root mean square error of approximation | RMSEA | 0.051 | ≤0.08 |

| Tucker-Lewis index | TLI | 0.98 | ≥0.95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kariri, H.D.H.; Radwan, O.A. The Influence of Psychological Capital on Individual’s Social Responsibility through the Pivotal Role of Psychological Empowerment: A Study Towards a Sustainable Workplace Environment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2720. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032720

Kariri HDH, Radwan OA. The Influence of Psychological Capital on Individual’s Social Responsibility through the Pivotal Role of Psychological Empowerment: A Study Towards a Sustainable Workplace Environment. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2720. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032720

Chicago/Turabian StyleKariri, Hadi Dhafer Hassan, and Omaymah Abdulwahab Radwan. 2023. "The Influence of Psychological Capital on Individual’s Social Responsibility through the Pivotal Role of Psychological Empowerment: A Study Towards a Sustainable Workplace Environment" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2720. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032720

APA StyleKariri, H. D. H., & Radwan, O. A. (2023). The Influence of Psychological Capital on Individual’s Social Responsibility through the Pivotal Role of Psychological Empowerment: A Study Towards a Sustainable Workplace Environment. Sustainability, 15(3), 2720. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032720