Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to help better understand the problem of energy poverty; to grasp the research context, evolution trends and research hotspots of energy poverty; and to find clues from research on energy poverty. In this paper, we use the scientific quantitative knowledge graph method and CiteSpace software to analyze 814 studies in the WOS (Web of Science) and CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) databases, such as a literature characteristic analysis, a core author and research institution network analysis, a research hotspot analysis, research trends and a frontier analysis. The results show that the specific connotations of energy poverty are different between developed countries and developing countries. In developed countries, energy poverty is mainly manifested in the affordability of energy consumption, while in developing countries, energy poverty is manifested in the availability of energy. The causes, impacts and solutions of energy poverty are the focus of CNKI and WOS literature, and their perspectives of the impacts and solutions are relatively consistent. However, in terms of the causes, scholars of WOS discuss the energy supply side and the demand side, while scholars of CNKI mainly analyze the energy demand side. The quantitative evaluation system of energy poverty has not been unified, which restricts the depth and breadth of energy poverty research. Topics such as the expanding scope of research objects; the interaction among energy poverty, the “two-carbon” target and other macro factors; the complex and severe energy poverty situation following the COVID-19 pandemic and the outbreak of the war in Ukraine; and the ways to solve the energy poverty problem in the context of China may become the focus of research in the future. This study provides an overview for researchers who are not familiar with the field of energy poverty, and provides reference and inspiration for future research of scholars in the field of energy poverty research.

1. Introduction

Energy is essential for economic growth. Energy poverty has become an essential issue in politics for all countries around the world and has received significant attention from academic circles. The United Nations started the Sustainable Energy for All initiative to address the issue of energy poverty, and 2012 was designated as the “International Year of Sustainable Energy for All” to ensure that everyone has access to modern energy services and to significantly increase energy efficiency by the year 2030. As the biggest developing country, China also faces a severe energy poverty problem. In 2022, the National Development and Reform Commission and the National Energy Administration of China issued the Implementation Plan on Promoting the High-quality Development of New Energy in the New Era, emphasizing that the total capacity of wind power and solar power should reach over 1.2 billion kW by 2030 and emphasizing the need to speed up the construction of a clean, low-carbon, safe and efficient energy system. This plan will give full play to the role of new energy sources in ensuring energy supply and increasing energy supply and will contribute to carbon peaking and carbon neutrality. In 2022, following the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, international energy prices reached a historic high and the energy cost of European residents increased rapidly. Some European countries restarted coal-fired power plants and actively sought to switch from Russian natural gas suppliers to other suppliers to overcome a series of energy poverty problems caused by the energy shortage and the rising energy costs. The continued tension between Russia and Ukraine and the persisting game of interests among major powers further increase the complexity of the energy poverty situation.

The purpose of this paper is to help better understand the problem of energy poverty; to grasp the research context, evolution trends and research hotspots of energy poverty; and to find clues from research on energy poverty. In recent years, scholars have explored energy poverty from a variety of perspectives, such as different concepts and assessments of energy poverty; different causes, impacts and solutions of energy poverty; etc., but some issues still need to be researched in depth and studies that measure and comb the literature are still lacking. In order to fill this gap, in this paper, we adopt the literature metrology method to systematically comb the literature on the 10-year energy poverty problem. First, the connotations and boundaries of energy poverty are still blurred. Some scholars believe that energy poverty and fuel poverty cannot be distinguished [1]. Additionally, no consensus exists on the measurement of energy poverty, and the existing literature measures energy poverty from different perspectives [2,3,4]. Moreover, in addition to the various concepts and measurement methods of energy poverty, a considerable amount of literature has analyzed the causes or influencing factors of energy poverty in order to explore the key causes of energy poverty [4,5,6,7]. Some scholars have tried to explore the impact of relevant influencing factors on energy poverty from both macro and micro perspectives [2,5,6]. From the existing literature, systematic sorting of the research status and research topics on energy poverty is still lacking, and there is still ample space to explore the contents and level of the research on energy poverty. In particular, the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the outbreak of the war in Ukraine on countries around the world will make energy poverty more complex and serious. In this study, CiteSpace software (5.8.R3 and 6.1.R6) was used to systematize and analyze the energy poverty literature of the WOS and CNKI databases from 2011 to 2021. On the one hand, our analysis provides an overview for researchers who are not familiar with the field of energy poverty. On the other hand, our analysis provides a reference and inspiration for future research by experts in the field of energy poverty research.

2. Research Methods and Data Sources

2.1. Research Methods

As a new method and field of scientometrics, knowledge graphs have been widely used in literature searches. A knowledge graph displays the complex relationship among numerous information units or information gatherings, including the structure, interaction, intersection and evolution of the network. Knowledge graphs can be utilized to investigate the development status, the research areas of interest, the frontiers, and the trends and have many advantages, such as being intuitive to use and producing objective results. CiteSpace software mainly uses co-citation analysis theory and the path finder algorithm, etc. to measure the literature (sets) in specific fields to find out the critical path and knowledge inflection point of the evolution of a subject domain and uses a series of visualization maps to form an analysis of the potential dynamic mechanism behind a discipline’s evolution and the exploration of frontiers in that discipline’s development [8]. In this study, CiteSpace software, developed by Professor Chen Chaomei was used to process literature data. The time distribution, authors, keywords, etc. of energy-poverty-related papers published after 2011 are visually analyzed. Additionally, we generated intuitive knowledge maps of keyword co-occurrence, keyword clustering, burst words, etc., to sort out and analyze the research hotspots and research trends of energy poverty.

2.2. Data Sources

The data came from the WOS (Web of Science) and CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) databases. Web of Science is a large, multidisciplinary core journal database the covers the world’s three most authoritative citation index databases and includes information on hundreds of countries and regional institutions around the world. To a large extent, the literature indexed in Web of Science is representative of the research on global energy poverty. Therefore, in this paper, we chose the WOS database as the literature source of countries other than China. The Web of Science database was searched for the topic “energy poverty”. In order to ensure the quality and integrity of research samples, the core collection of WOS was selected as the sample source of foreign literature (including SCI-Expanded and SSCI). CNKI is an internationally leading online publishing platform that integrates periodicals, doctoral dissertations, master’s dissertations, conference dissertations and other resources. In this paper, we chose CNKI as the source of CNKI literature. We searched in CNKI for the subject “energy poverty” and selected core journals and CSSCI journals as sample sources. To a large extent, these two types of literature are representative of the general literary situation and academic frontiers in energy poverty research in China. Since few studies have been conducted on energy poverty in WOS and CNKI before 2011, the earliest publication date for retrieved papers was set to 2011, and the retrieval was carried out on October 26, 2021. Therefore, the time span was set from January 2011 to October 2021, the time slice was set to 1 year, and CiteSpace was used to import the data. In total, 793 WOS papers and 21 CNKI papers were included in the final analysis.

3. Analysis of Literature Characteristics

3.1. Quantitative Characteristics of the Literature

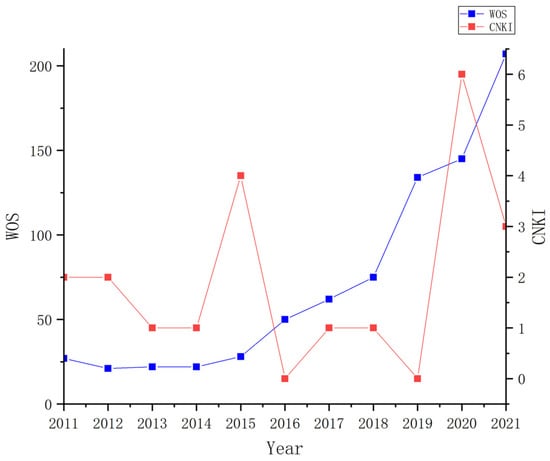

The yearly distribution of publications reflects the overall level, evolution trend, development speed and research development stages in a particular field. This distribution shows the focuses of scholars in this field at different time points. Figure 1 is a sample literature curve drawn from the yearly statistics.

Figure 1.

Annual distribution of energy poverty literature published, 2011–2021.

Figure 1 shows that, with the deepening of research on energy poverty, scholars focus more on energy poverty, and the quantity of published papers shows a rising trend. According to the papers published each year, three stages can be distinguished in WOS literature on energy poverty. During the early stages of the research, from 2011 to 2015, a low volume of studies were published on energy poverty. However, the number of papers published rose quickly from 2016 to 2018, from 28 in 2015 to 50 in 2016. A sharp rise from 75 papers published in 2018 to 134 papers published in 2019 could be seen. When looking at 2018 as an inflection point, the number of articles released revealed a tendency to rapidly rise.

In contrast, a big gap exists between the number of papers published by WOS and CNKI. During the statistical period, only a total of 21 papers were published. Currently, CNKI research on energy poverty is still in its primary stage. Although poverty alleviation has always been the focus of the Chinese government, few research findings have been found on the subject of energy poverty in CNKI literature, and the relevant research has not formed a good development trend. There is a big gap within WOS literature research. The reason for this phenomenon may be because the connotations of energy poverty in developed countries and developing countries are different. Energy poverty in developed countries is manifested as the affordability of energy, while energy poverty in developing countries is manifested as the availability of energy [9]. When developing countries face the constraints of energy availability, the problem of economic poverty may become more serious and receive more attention.

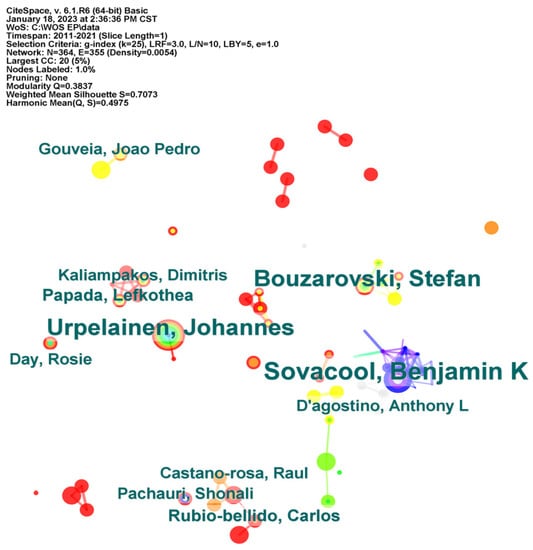

3.2. Core Author Analysis

In this paper, an author cooperation network map is used for the core author analysis. An author cooperation network map can reflect the status of an author in a specific research field and the closeness of the cooperation network. Node size in the graph represents the number of published papers and is positively correlated with the number of published papers. The lines between nodes represent whether a cooperative relationship is present between authors, and there is a positive correlation between line density and cooperation intensity. The authors of the sample WOS literature were analyzed and processed to form the core author network of the WOS literature (Figure 2). There were 364 nodes in the atlas, 355 connections and a network density of 0.0054. Some authors cooperate closely, but the overall degree of connection was not strong and did not form a trend of extensive cooperation. In terms of country, the countries of the core authors were mainly distributed in the United Kingdom, the United States, Greece, Austria, Portugal, and other European and American developed countries. The top three core authors include Sovacool, Benjamin K. (21 times); Urpelainen, Johannes (17 times); and Bouzarovski, Stefan (17 times). Sovacool, Benjamin K. mainly studied the complexity of energy poverty, fuel poverty, energy security, energy justice, etc. He offered a framework for energy justice given fairness, responsibility, sustainability, accessibility, affordability, due process, transparency and accountability. In addition, the relationship among the COVID-19 pandemic, energy supply and demand, energy governance, the coming low-carbon transition and social justice, etc. are some of Sovacool, Benjamin K.’s areas of research interest. Urpelainen, Johannes focused on India’s measures and paths to energy poverty, including electricity, fuel, distributed renewable energy, etc. He discussed the need for energy policy change and highlighted the importance of socio-economic development for rural electricity access, and the impact of reducing population density in remote areas on grid expansion. He also thoroughly discussed the development of the regional solar lighting market. Bouzarovski, Stefan worked on multidimensional energy poverty indexes, vulnerability to energy poverty, related institutional policies, etc. He critically evaluated existing statistical indicators for monitoring energy poverty and proposed directions for improvement. At the same time, he created multidimensional indexes to explain the five dimensions of energy poverty. He pointed to the idea that political progress in addressing energy inequality was based on symbolic strategies, challenging the narrative of personal responsibility that treats people who are vulnerable as individually responsible for their own deprivation.

Figure 2.

Network map of the core authors in WOS.

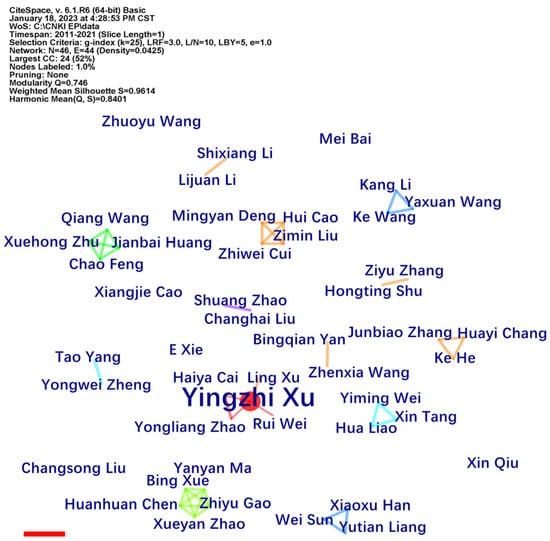

The core author network of the CNKI literature was formed by analyzing the sample literature of CNKI (Figure 3). There were 46 nodes in the atlas, 44 connections and a network density of 0.0425. The core author network map of the CNKI literature has characteristics of a “small concentration and large dispersion”. Although academic cooperation can be seen among the authors, the overall distribution is relatively scattered. Regarding the number of published papers, the core CNKI literature author was Professor Yingzhi Xu (3 times) from the School of Economics and Management of Southeast University in China. At the same time, by conducting a thorough analysis of the pertinent literature on energy poverty in the CNKI literature, we found that Prof. Hua Liao et al., Beijing Institute of Technology, examined the state of energy poverty research for the first time. He built a foundation for studying energy poverty and established an overall framework for research on energy poverty, laying a foundation for research on energy poverty in CNKI literature [10].

Figure 3.

Network map of the core authors in CNKI.

3.3. Research Institution Analysis

In this paper, the research institution network diagram was used to analyze research institutions. The research institution network diagram displays the cooperation among research institutions and can reflect the status of research institutions and the tightness of the cooperation network among institutions. Among them, the size of the nodes represents the number of papers published by research institutions, and the larger the node, the more published papers. The lines between the nodes represent whether a cooperative relationship is present between research institutions. As shown in the map of the research institution network of WOS (Figure 4), there are 312 nodes and 249 connections in the map. Researchers with more than 15 publications included University of Seville (21 times), The University of Manchester (18 times), National Technical University of Athens (17 times), Columbia University (16 times) and The University of Queensland (15 times). These institutions are located in five countries: Spain, the United Kingdom, Greece, the United States and Australia, respectively. The above institutions have high authority in energy poverty research. From the point of view of the closeness of node connections, the density of the map is 0.0051, indicating that not much research cooperation occurs among institutions.

Figure 4.

Institutional cooperation network for WOS literature.

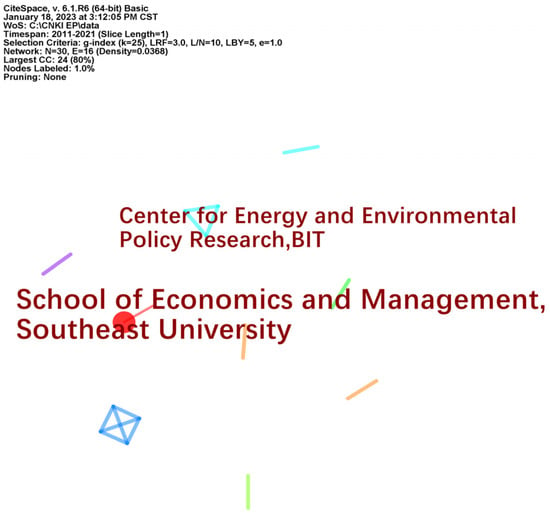

In the network map of publishing institutions in the CNKI literature, a total of 30 nodes and 16 links were generated, and the institutions with more than two publications were the School of Economics and Management of Southeast University (3 times) and the Energy and Environmental Policy Research Center of Beijing Institute of Technology (2 times) (Figure 5). The density of the cooperation network of research institutions is 0.0368, with the low density indicating that a weak cooperation relationship among institutions in the CNKI literature.

Figure 5.

Institutional cooperation network for CNKI literature.

Regardless of whether we consider the cooperation network for authors or institutions, the degree of cooperation in CNKI literature is higher than that in WOS literature. The reason for this may be because the research objects of the CNKI literature mainly focus on regions within China, while the research objects of the WOS literature are widely distributed, inclusive of the European Union, India, some African countries and other countries, and each country has its own characteristics of energy poverty. Therefore, the possibility of collaborative research is low.

4. Analysis of Research Hotspots

A knowledge graph usually uses keywords, citation frequencies and other indicators to analyze and judge a field’s research hotspot and frontier. Keywords are words that repeatedly appear in the title, topic, abstract and full text of the literature. Additionally, they are the words that best characterize the research area. The research hotspots, changing rules and development trends in this area can be identified by examining the frequency of occurrence of terms and by creating a keyword co-occurrence network. Therefore, in this study, we compare the research hotspots of WOS and CNKI literature using a keyword co-occurrence network. By analyzing the occurrence frequency, a keyword co-occurrence network is constructed, and the network nodes represent the occurrence frequency of keywords to clearly show the distribution of high-frequency keywords in this field, then to discover the research hotspots, and to change the rules and development trends of the research object. In this study, we compare the research hotspot of energy poverty in the WOS and CNKI literature based on a keyword co-occurrence network.

4.1. Research Hotspots of WOS Literature

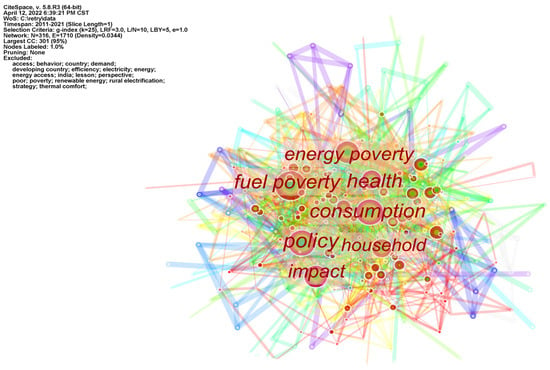

A keyword co-occurrence analysis of the WOS literature on energy poverty was conducted (Figure 6), and the generated keyword network map had 316 nodes, 1710 connections and a network density of 0.0344. The top four keywords with the highest frequency were “fuel poverty” (174 times), “consumption” (103 times), “policy” (92 times), and “impact” (91 times). “energy poverty,” “household” and “health” ranked fifth, sixth and seventh with 84, 66 and 63, respectively. The above high-frequency keywords reflect the research focus of the WOS literature.

Figure 6.

Network map of keywords for WOS literature.

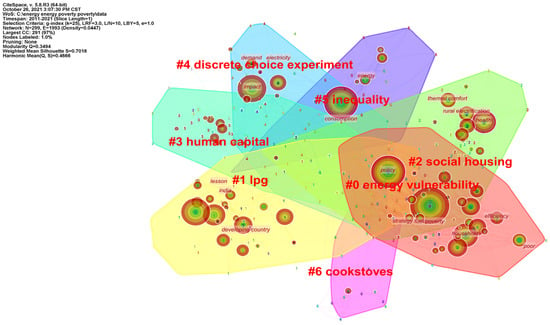

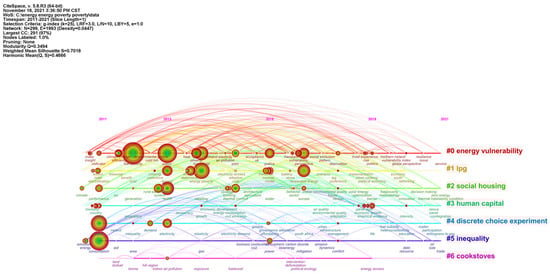

CiteSpace provides two indexes—module value (Q value) and average contour value (S value)—according to the network structure and the clarity of clustering as the basis for evaluating the rendering effect of the map. Generally speaking, when the Q value is greater than 0.3, clustering is significant; when S value is 0.7, clustering is efficient and convincing; if it is above 0.5, clustering is generally reasonable [8]. The keywords in WOS were clustered (Figure 7), and the Q value was 0.3494 while the S value was 0.7018, indicating that the clustering structure was significant and reasonable. The keywords were divided into seven categories through a cluster analysis, #0 for energy vulnerability; #1 for LPG, 2# for social housing, #3 for human capital, #4 for discrete choice experiment, #5 is inequality and #6 is cookstoves. Based on the results of the keyword clustering, keyword co-occurrence maps and the specific contents of the related literature, the research hotspots on energy poverty for WOS can be classified into the following three categories of research topics.

Figure 7.

Network map of keyword clustering for WOS literature.

4.1.1. Energy Structure and Energy Poverty

The first topic is “energy structure and energy poverty”, including keywords such as “cookstoves”, “LPG,”, “clean cooking,”, etc. According to the existing literature [11,12,13], transforming the energy structure and governance model will significantly impact energy poverty. Regardless of the severity of energy poverty, people generally prefer to use modern energy for cooking and lighting [11]. Expanding the range of fuel types for stoves available to families will lead to benefit such as improvements in energy security and energy efficiency [12]. In terms of expanding the range of fuels, Yadav, P. et al. [13] pointed out the obstacles to the successful deployment of solar photovoltaics, including the disconnection between policymakers and implementers and the coordination problems within and among participants. In addition, optimizing the energy structure, exploring related factors that hinder the usage of new energy and increasing the proportion of clean energy consumption have become meaningful ways to solve the problem of energy poverty. For example, these solutions support the electrification of rural areas and encourage the use of modern cooking fuels in the countryside [14]. Nevertheless, increasing the proportion of clean energy consumption takes work. Kumar, P. et al. [15] suggested that comprehensive promotions to adopt clean energy should be carried out in communities by cultivating new social relations and by reforming the existing social structure. Furthermore, attention should be paid to the importance of enterprises in spreading the alternative role of clean energy. The research conclusions of Perez, J. et al. [16] were consistent with this statement, and making corresponding efforts from the social level, such as education, is also suggested. Based on a study of household cooking fuel in Colombia, with the improvement in overall education level, the probability of choosing liquefied natural gas over other cooking fuels was found to be multiplied. The government is recommended to invest more in clean energy.

From the practice of alleviating energy poverty, the development of renewable energy has become the core and key to achieving global energy transformation and sustainable development. The rapid development of the renewable energy industry is conducive to improving energy efficiency and alleviating energy poverty [17]. After the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, Europe also increasingly considered the supply of renewable energy as an important means to deal with the medium and long-term energy crises and introduced the REPowerEU policy to increase investments into renewable energy [18].

4.1.2. Energy Vulnerability and Energy Poverty

The second topic is “energy vulnerability and energy poverty”. Some of the keywords include “energy vulnerability”, “energy access”, “willingness to pay”, etc. On the one hand, energy vulnerability may cause energy poverty; on the other hand, energy vulnerability may further deepen the adverse effects of energy poverty’s impacts. Energy vulnerability is mainly caused by household income, housing characteristics and energy consumption habits of household members. Various elements that cause energy vulnerability at the family level are connected to energy destitution. Therefore, intervention measures targeting the causes of energy vulnerability also apply to energy poverty [19]. In addition, income is a particularly critical factor among the many factors leading to energy vulnerability. In their research, Nguyen, C. P. et al. [20] found that income inequality exacerbates energy poverty and that, when energy poverty is alleviated, income inequality will also be improved. Therefore, when formulating energy policies, policies targeting energy poverty may be applicable to income inequality. The research of Okushima, S. [21] supports the views of Nguyen, C. P. et al. [20]. Okushima, S. [21] found that groups of people from lower socio-economic backgrounds have greater demands for carbon emissions and more income expenditures due to lower energy-use efficiencies and inefficient energy procurement. This intensifies the negative feedback loop between energy poverty and low income. From the perspective of population characteristics, if population characteristics are different, energy vulnerability, as well as the severity of energy poverty, will differ significantly. Energy poverty is particularly severe in rural and hilly locations. The focus of energy policies should shift toward rural and mountain residents, and social inequalities caused by energy poverty should be addressed by reducing heating costs for rural and mountain residents [22]. In addition to household income, residential characteristics and the energy usage habits of household members, energy cost and energy efficiency are also important contributors to energy vulnerability. When energy poverty levels are the same, energy-vulnerable households suffer more significant negative impacts [23].

4.1.3. Impact of Energy Poverty and Solutions

The final theme is energy poverty’s effects and potential solutions, including the keywords of “social housing”, “human capital”, “urbanization”, etc. At the macro level, energy issues are related to national security, economic development, social equity and energy equity [24,25,26]. Based on the perspective of energy equity, in addition to establishing a perfect system, we should also consider the costs and benefits of energy services from the perspective of energy services to make a comprehensive and equitable energy decision. From the micro-impact level, energy poverty can hurt residents’ physical and mental states, perceptions of happiness and health statuses [26,27]. In addition to optimizing the energy structure, some literature also seeks solutions from the systems, policy, economy and technology perspectives. For example, some scholars believe that political progress is a critical way to solve energy poverty from a strategic level. Among these solutions, political progress is mainly reflected in the general awareness of energy poverty in society and the re-examination of social responsibility of vulnerable groups [28]. Some scholars have found that sub-Saharan Africa’s political and economic development has effectively changed the local energy poverty problem after decades of development [7].

At the micro level, improving energy efficiency is a necessary technical means to solving energy poverty. However, the generation of technical effects needs to be based on the change in household energy consumption preferences [29]. Concerning the effect of energy poverty on occupants’ view of satisfaction and well-being, energy poverty can negatively impacts inhabitants’ subjective well-being [30]. Furthermore, the impact of energy poverty on health is more significant than that of marriage, employment, income and education [31]. In addition, energy poverty is highly inversely correlated with children’s health and later educational performance [32]. Families with children are more likely to fall into energy poverty [33]. In addition, political and economic progress has shown considerable dynamism in combating energy poverty [7]. For instance, political and economic processes play important roles in shaping the flow of electricity in rural Africa [34]. At the same time, initiatives to use more environmentally friendly energy sources also alleviate energy poverty [35].

4.2. Research Hotspots of CNKI Literature

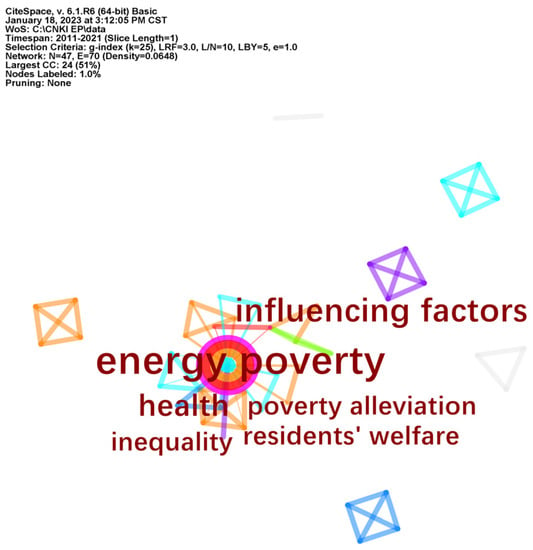

Figure 8 shows the frequency of the keywords retrieved from CNKI. The number of nodes is 47, the number of connections is 70, and the network density is 0.0648. The top two keywords with the highest frequencies were “energy poverty” (10 times) and “influencing factors” (3 times). “China” and “health” (2 times) were tied for third place.

Figure 8.

Network map of keywords for CNKI literature.

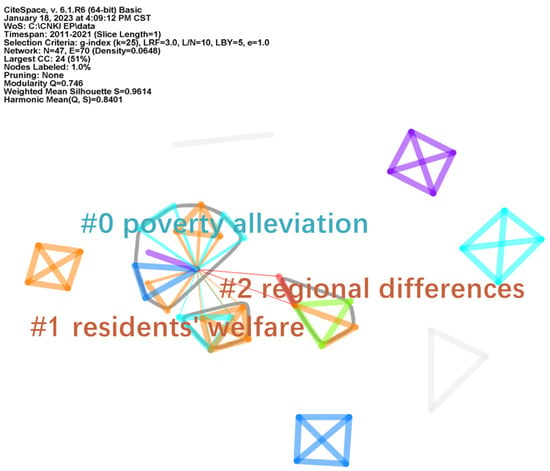

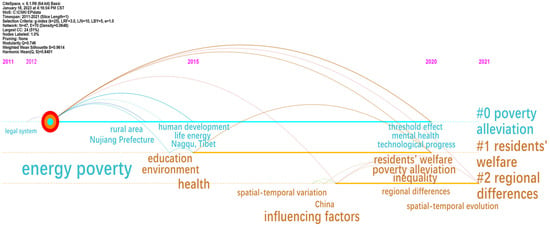

According to the keyword clustering results retrieved from CNKI (Figure 9). The Q value was 0.746 and the S value was 0.9614, indicating that the clustering structure was significant and reasonable. The keywords of the CNKI literature can be divided into three clusters, #0 for poverty alleviation, #1 for residents’ welfare; #2 is regional difference. Based on the clustering results, keyword co-occurrence maps and the specific contents of relevant literature, the CNKI literature can be divided into two topics.

Figure 9.

Network map of keyword clustering for CNKI literature.

The first topic is “causes of energy poverty”, including “regional difference”, “temporal and spatial changing”, “influencing factors” and other keywords. First, household income may be the most critical factor causing energy poverty. Chang Huayi et al. [5] called the energy-use dilemma caused by economic poverty the “trap” of energy poverty, so energy poverty is more common among low-income families. Energy poverty will be mitigated with the improvement of the economic growth level. However, with the increase in the energy price level, energy poverty is also likely to worsen [6]. In addition to income factors, inefficient cooking and heating behaviors [10] and even psychological factors may cause energy poverty. For example, residents who are pessimistic about the future may be more inclined to use traditional energy, may be reluctant to change energy consumption behaviors and may have a lower acceptance of energy policies [5]. In addition, still no agreed-upon method is used by the authors of the literature indexed in CNKI to choose the indicators that will be used to measure energy poverty. For example, Xie E [2] constructed a multidimensional energy poverty index from five aspects: fuel, lighting, home appliance services, entertainment/education and communication. Based on energy access and energy services, Zhao Xueyan et al. [36] calculated the level of energy poverty in rural China.

The second topic was “the impact of energy poverty”, with keywords such as “household welfare”, “inequality” and “health.” Specifically, energy poverty harms residents’ welfare levels, and physical and mental health. Zhang Ziyu et al. [37] found that energy poverty harms residents’ physical and mental health and hurts residents’ mental state, happiness, social class and perception of social equity. However, regional and gender differences show different degrees of adverse effects. The research by Wang, Zhenxia et al. [38] echoed the research conclusions of Zhang Ziyu et al. [37]. Wang Zhenxia et al. [38] believed that energy poverty’s adverse effects on residents’ welfare are affected by household income and that the welfare level of low-income groups is more damaged. There is a transmission mechanism that follows “energy poverty–health/inequality–residents’ welfare” from the standpoint of the path of the impact of energy poverty on residents’ welfare. Energy poverty and targeted poverty alleviation may be strongly correlated, but in current academic research, this correlation has not attracted enough attention from scholars in the CNKI literature [39]. However, energy poverty has become fundamental in the new destitution issue in China’s rural regions. Energy poverty alleviation is of extraordinary importance in consolidating the results of poverty alleviation [40]. In addition to the welfare level and residents’ health, the negative consequences of energy poverty also include the adverse effects on China’s inclusive green development [41] and individual education level [2].

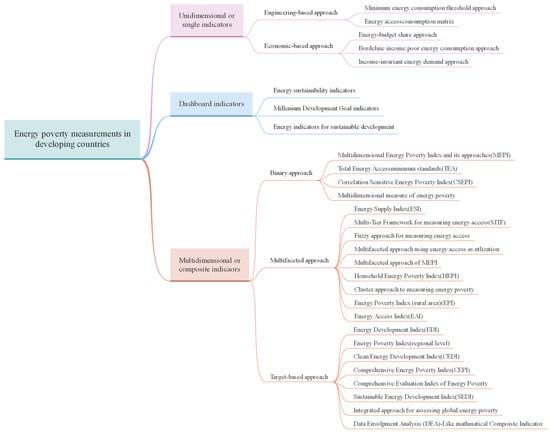

4.3. Evaluation Index of Energy Poverty

The analysis of each hot topic involves the evaluation or measurement of energy poverty. An accurate measurement of energy poverty is the premise of carrying out an analysis of various related topics. At present, the energy poverty assessment index is very important for research on energy poverty, but developed and developing countries have not unified their assessment indexes for energy poverty and research on energy poverty assessment indexes has become a hot issue to which scholars will continue to pay attention. In general, evaluation indicators can be divided into three categories: single indicators, dashboard indicators, and composite indicators [9]. The single indicators only measure and evaluate a certain aspect of energy poverty and can be divided into engineering measurement and economic measurement [9,42,43]. The dashboard indicators are a collection of non-summary indicators that reflect the overall picture of a country or region’s energy system and their progress towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. The dashboard indicators are mostly developed by international organizations such as the United Nations and take into account multiple macro factors such as economy, society, environment and technology, such as the sustainable development energy index developed by the United Nations [44]. The composite indicators are a collection of multiple single indexes, through index synthesis; weight determination; and finally, merger into a compound index, for example, the exploration of energy poverty evaluation indicators from the aspects of household clean energy consumption and energy consumption expenditure [3]. Sy S A et al. (2022) [9] systematically sorted out three types of energy poverty indicators, as shown in Figure below (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Measurements of energy poverty.

5. Research Trends and Frontier Analysis

5.1. Research Trends

In order to better understand the evolution trend of energy poverty research in WOS and CNKI literature in different periods, we present the keyword clustering results of sample literature in the timeline to show the time changes of keywords in each category. Among them, circles represent research hotspots. The larger the circles, the greater the scholars’ interest in related topics; the darker the circles, the greater the importance of related topics.

By observing the time axis of critical words in the energy poverty literature (Figure 11), the evolution path of research in the WOS literature on energy poverty can be divided into three essential time stages: 2011–2013 was the early stage of development, and most scholars focused on the connotation, composition, function, and elements that affect energy poverty. From 2014 to 2018, research on energy poverty began to take shape at this stage, and studies on the role and influencing factors of energy poverty further expanded. In addition, new research topics such as public housing began to emerge, and researchers’ focus gradually switched to the energy structure and how energy poverty affects residents’ welfare. From 2019 to 2021, studies on the role of energy poverty and its influencing factors were conducted on an ongoing basis, but issues about the interactive relationship between energy poverty and human capital began to break out. Scholars paid more attention to the key impacts of energy poverty on human capital and the role of human capital in solving energy poverty, such as the relationships between employment, income, and educational achievement and energy poverty.

Figure 11.

Timeline of keywords for WOS literature.

The keyword clustering timeline of the CNKI literature (Figure 12) shows that energy poverty research is mainly divided into two essential time stages: from 2011 to 2012, energy poverty research in the CNKI literature was in the embryonic stage, with few research results, and failed to form a large-scale theme. From 2012 to 2021 is the development stage, when keywords such as human development, poverty alleviation, residents’ welfare, and inequality began to appear, Chinese scholars began to pay attention to the influencing factors and the impact of energy poverty on residents’ welfare, and the research angle expanded from static to spatial–temporal changes.

Figure 12.

Timeline of keywords for CNKI literature.

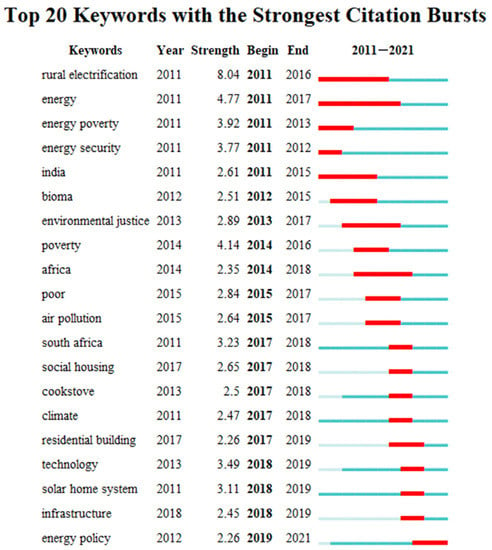

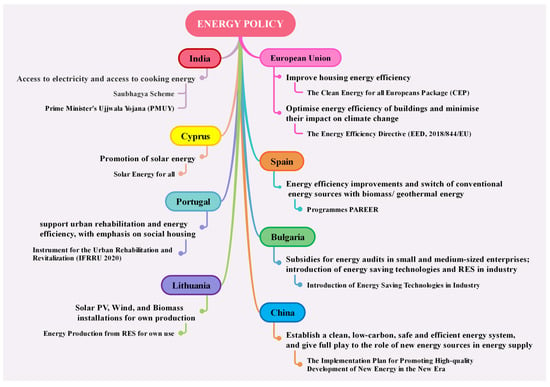

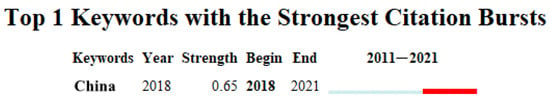

5.2. Research Frontier Analysis

A burst analysis is a way to measure changes in deeper research topics. In a burst analysis graph, Begin and End represent the start and end times of the keyword burst during the study period. Strength represents the burst intensity; the red line reflects the duration of the keyword burst, and the blue line is the time slice in a year. A burst analysis of the WOS literature is shown in Figure 13. From the perspective of the burst words in the WOS literature, the two burst words rural electrification and energy have durations of more than five years, while the three burst words India, environmental justice, and Africa have durations of 4 years. In terms of burst intensity, rural electrification, energy, energy poverty, energy security, poverty, South Africa, and technology and solar home system have burst intensities of more than 3. From the perspective of a sudden end time, the end times of the five keywords are within four years: the end times of infrastructure, solar home system, technology and residential building are 2019, while the studies on energy policies are still ongoing, as of 2021. In recent years, various governments have alleviated the negative effects of energy poverty by means of energy policies to solve the worsening of energy poverty caused by a lack of energy policies. By combing through the relevant literature [3,28,45], the energy policies of some countries can be obtained, as shown in the table below (Figure 14). In general, the energy policies in the table below include two aspects: to improve the energy efficiency of houses/buildings, including The Clean Energy for all Europeans Package (CEP) and The Energy Efficiency Directive (EED, 2018/844/EU) in the European Union, and the Instrument for the Urban Rehabilitation and Revitalization of Portugal (IFRRU 2020) in Portugal. The other type of energy policy aims at increasing the supply of clean/modern energy sources, including the Saubhagya Scheme and Prime Minister’s Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY) in India, Solar Energy for all in Cyprus, Programmes PAREER in Spain, Bulgaria’s Introduction of Energy Saving Technologies in Industry, Lithuania’s Energy Production from RES for own use and China’s Implementation Plan for Promoting High-quality Development of New Energy in the New Era. Part of the literature starts with policies related to energy poverty and points out that energy-poverty-related policies reflect issues such as the government’s governing ability and political culture [46]. The political benefits or adverse political consequences of successful or failed energy policies are also the focus of scholars’ attention.

Figure 13.

Top 20 keywords with the strongest citation bursts in the WOS literature.

Figure 14.

Part of the energy policy of some countries that address the problem of energy poverty.

Through a burst analysis of the CNKI literature (Figure 15), we found that only when the threshold is adjusted below 0.3 was a burst word generated. The reason for the few burst words may be related to the few studies in the energy poverty literature in CNKI. As the only burst word, studies focused on “China” are ongoing, as of 2021, totaling four years at that time. This result indicates that the authors of studies in the CNKI literature will continue to focus on research on energy poverty in China.

Figure 15.

Top 1 keyword with the strongest citation burst in the CNKI literature.

6. Research Conclusions and Prospects

6.1. Research Conclusions

Energy poverty is an important social issue and research hotspot [4], in particular, the outbreak of the war in Ukraine in 2022, the increasing sanctions against Russia by Western countries including the European Union, increasing investor nervousness, the huge volatility in the international energy market, global natural gas and electricity prices reaching record levels, and the level of energy poverty in all countries around the world have increased. In Australia, for example, electricity prices will remain high for at least three years [47]. In Europe, the war in Ukraine has become a flashpoint for the energy crisis. For a long time, the EU has been moving too fast in their green and low-carbon transition, with the supply of new energy being unstable. After the breakdown of energy relations between Russia and Europe, Europe experienced a crisis of energy shortage and market disorder [18]. Before the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, no studies currently discuss the rapid rebound in energy prices caused by the suspension of Russian gas supplies to Europe. In addition to Europe, the energy crisis has caused increased energy poverty in developing countries in Asia and Africa. Until now, some African countries have alleviated energy poverty to some extent by improving modern energy supplies [7], but with the increase in global energy prices and a still-developing economy, the possibility of obtaining modern energy will also decrease. For emerging economies such as those of China and India, energy prices have risen rapidly despite slow economic recovery from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to increased energy poverty among low-income groups. At the same time, energy poverty affects residents’ welfare, physical and mental health, and many other aspects, but the academic community has not paid much attention to the issue of energy poverty. After the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, many politicians and famous commentators called for attention to energy poverty and the global energy crisis. In this study, we sorted and reviewed the research context of energy poverty through a literature search. The hope is to attract more attention from the academic community on energy poverty.

This paper used Citespace software to visually analyze the literature on energy poverty in WOS and CNKI. Through an analysis of the keywords, keyword clustering, timeline and burst words, etc., we found the following results:

First, as for the richness of the research, from the number of publications, the network diagram of core authors and the network diagram of research institutions, a big gap between the richness of the research in studies found in CNKI and WOS can be seen. This issue arises possibly because energy poverty has distinct meanings in developed and developing nations. For developed countries, energy poverty focuses on the affordability of energy consumption, which is a conflict between income and the need for cleaner energy. For developing countries, energy poverty focuses on energy availability and manifests as difficulties in obtaining fuel to meet survival needs. In addition to energy poverty, economic poverty is more severe in developing countries, so they give substantially more consideration to economic poverty alleviation than energy poverty alleviation. In addition, there are differences in the degree of cooperation between WOS and CNKI authors and research institutions, but both are at a low level and need to be improved. Among them, the degree of cooperation among authors and institutions of the studies in CNKI is slightly higher than that of WOS. Their reason for this may be because the research objects of CNKI literature mainly focus on regions within China, while the research objects of WOS literature are more widely distributed.

Second, as for the research hotspots, scholars of the WOS literature mainly focus on energy structure and energy poverty, energy vulnerability and energy poverty, and the impacts and solutions of energy poverty. The CNKI literature primarily focuses on the causes and effects of energy poverty. Through a comparison of these research hotspots, scholars of the WOS and CNKI literature are clearly focused on energy poverty’s causes and repercussions. However, the causes of energy poverty are different for different countries and regions The scholars of the WOS literature focus on two causes: energy structure and energy vulnerability. In contrast, the scholars of the CNKI literature mainly focus on income, economic development, energy-use habits, and other factors. The reason for focusing on different causes may be because China’s current energy poverty problem is reflected more in the availability of energy, economic development level, resident income, energy consumption habits and other vital causes, while the concerns of energy structure from scholars of the WOS literature are reflected more in residents’ demands for clean energy consumption, namely the affordability of high-quality energy. In addition, how to alleviate energy poverty through the development of renewable energy is also the focus of academic attention.

Thirdly, regarding research trends, the interaction between energy poverty and policies has become the focus of scholarly attention in recent years. Studies in the WOS literature have conducted in-depth research on issues such as energy poverty, and energy policies are continuously being updated. However, the CNKI literature has not yet formed a systematic research system. However, research based on the Chinese context on ways to address the issue of energy poverty through a socialist economic system and a distribution system with Chinese characteristics and to promote social justice, especially under the risks and challenges caused by climate change, may contribute transferable knowledge and solutions to the global energy poverty problem. In particular, scholars have yet to form a unified standard for selecting energy poverty assessment indicators. On the one hand, energy poverty has a different meaning in developing countries than in developed countries, with the affordability of energy consumption and utilization efficiency being the main concerns of energy poverty in developed countries and the problem of energy availability caused by infrastructure constraints being more reflected in developing countries [28]. On the other hand, the reason is the availability of energy data. For example, Chinese scholars construct relevant evaluation indicators based on the data from social survey [2,5]. Therefore, as a unified assessment index is fundamental, how to establish a unified quantitative assessment index and method of energy poverty may become the direction of further exploration by scholars.

6.2. Focus of Future Research

Firstly, the object and contents of the research on energy poverty should be updated on an ongoing basis. From the perspective of research objects, many studies focus on developing countries such as India and China. However, due to the outbreak of Ukraine war in 2022, the energy prices of oil, gas and electricity in the international market have risen rapidly, and a considerable number of residents in developed countries are also facing severe energy poverty. Simshauser, P. (2022) [47] pointed out that the war in Ukraine has led to record-high prices for fuel, coal and natural gas on international markets and that, as spot prices in Australia’s National Electricity Market rose from AUD 75 to AUD 225/MWh, fuel poverty levels in Queensland will rise from 6.8 per cent to 10.5 per cent of households. Furthermore, a serious concern is the electricity forward curve that will remain elevated for at least 3 years. Therefore, in addition to continuing research on energy poverty in developing countries, energy poverty in developed countries should also be given renewed attention. Regarding the contents of this field of research, carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals have been established by the Chinese government, and these two goals have become definitive action guidelines for 2030 and 2060, respectively. However, unanswered questions that require more investigation still remain regarding the effects of the two goals on energy poverty, whether energy poverty will hinder the achievement of the two goals, and how energy poverty and the low-carbon transition will interact. In addition, energy poverty is a comprehensive reflection of political, economic, social, cultural, environmental and other issues. Therefore, the interaction among energy poverty, social equity and justice, economic development and system design, the influence of the interactions among various macro factors on energy poverty, and empirical studies on finding solutions to economic and social problems will be discussed at a higher level from the perspective of energy poverty, and research in the context of China’s energy poverty situation may contribute transferable solutions to the global energy poverty situation.

Secondly, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the outbreak of war in Ukraine, energy poverty should be paid close attention. Affected by the ongoing pandemic, governments of various countries have introduced policies to stimulate their economic growth and to increase the demand for energy. However, the outbreak of the war in Ukraine and the severe sanctions on Russia’s energy exports have led to a sharp decline in Russia’s oil and gas exports, and the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries and non-OPEC producers (“OPEC +”) are reluctant to increase production [18]. The subsequent increases in effective demand, geopolitical tensions and insufficient energy supply have caused global energy market volatility; energy prices have risen rapidly to historic highs; and the incidence of energy poverty has increased in all countries. In order to cope with this short-term energy shortage and these high electricity prices, some European countries such as Germany and the UK have begun to reuse coal plants and other nonrenewable energy sources. Does this mean that the process of ecological protection in Europe is moving backward? If so, how can we mediate the relationship between energy poverty and ecological protection? In addition, Europe is seeking new energy suppliers, in addition to their current Russian supplies, and will increase their renewable energy supply to cope with the medium and long-term energy crises. For example, Europe will establish oil and gas strategic cooperation with the United States and Canada and has proposes the REPowerEU plan to provide EUR 300 billion of investment into a renewable energy supply. Europe’s energy structure is bound to undergo major changes. What impact will this change have on energy poverty in Europe and other countries outside Europe? What are the implications of Europe’s response to the energy crisis on other countries? The outcome of the war in Ukraine also remains unclear. Therefore, research on the above issues has very important practical significance and academic value.

Thirdly, research on the impact of energy poverty in the Chinese context should be carried out on an ongoing basis. China is a vast country with considerable regional disparities in terms of development. The specific manifestations of energy poverty are also different. Since the 18th National Congress of the CPC, major strategic work such as green development, poverty eradication and rural revitalization have been carried out and promoted. The energy sector has also been exerting its advantages, focusing on deeply impoverished areas and promoting high-quality energy poverty alleviation work. For example, in 2014, The State Council put forward the Work Plan for Implementing Photovoltaic Poverty Alleviation Projects (PPAP), which reduced 6.32% of household energy poverty [48]. However, while achieving a series of significant achievements, new problems gradually emerged. For example, some local governments attach importance to assessing carbon emission tasks in achieving the carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals. However, they fail to consider how social and economic growth should be coordinated, leading to an imbalance between supply and demand when adjusting the energy structure, manifested as a significant problem of energy poverty: energy availability. These new problems also reflect the complexity of energy poverty. Furthermore, after successful poverty alleviation in China, we should pay more attention to how to further consolidate the achievements of poverty alleviation from the perspective of energy poverty alleviation and how to formulate programs to prevent a return to poverty. For example, the poverty standard should be changed from income poverty to multidimensional poverty, which includes energy poverty. Additionally, how to focus on industrial poverty alleviation and how to accelerate the development of poverty alleviation industries have become key issues that need to be urgently solved when exploring the method of energy poverty alleviation, especially for areas rich in wind, light and other new energy sources in less developed areas. In addition, in the implementation of the strategic deployment of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality, how to properly mediate the relationship between carbon emission reductions and economic development; how to optimize the pace and speed of energy structure adjustment; and how to determine the roles of coal, oil, natural gas and other energy research issues all deserve research attention. Therefore, according to the specific situation in China, analyzing the causes of energy poverty under different development situations and exploring solutions to energy poverty in depth are of great value for continuously promoting the development of poverty-stricken areas and all-round rural revitalization and for shaping sustainable development in China.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and J.Z.; methodology, J.Z.; software, J.Z.; validation, J.Z., X.L. and L.Z.; formal analysis, J.Z.; investigation, X.L. and L.Z.; resources, M.S.; data curation, X.L. and M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S.; visualization, J.Z.; supervision, X.H.; project administration, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project of Key Laboratory of Resource and Environmental Carrying Capacity Evaluation, Ministry of Natural Resources (No.:CCA2019.16), The Basic Research Fund Project of the Central University of China (No.:2022YJSGL08).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank the academic editors and anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bouzarovski, S.; Petrova, S. A global perspective on domestic energy deprivation: Overcoming the energy poverty–fuel poverty binary. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 10, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, E. Economic Impacts of Energy Poverty on Rural Households in China. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 2021, 41, 99–108+178–179. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Gupta, E.; Sarangi, G.K. Household Energy Poverty Index for India: An analysis of inter-state differences. Energy Policy 2020, 144, 111592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, G.E.; Gkampoura, E.-C. Evaluating the effect of economic crisis on energy poverty in Europe. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 144, 110981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; He, K.; Zhang, J. Energy poverty in rural China: A psychological explanations base on households. China Popul. Resoures Environ. 2020, 30, 11–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Y. Research on Temporal and Spatial Evolution Pattern and Influencing Factors of China’s Energy Poverty. Soft Sci. 2021, 35, 28–33+42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Munro, P.G.; Samarakoon, S.; van der Horst, G.A. African energy poverty: A moving target. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, Z.; Hu, Z.; Wang, X. The methodology function of CiteSpace mapping knowledge domains. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2015, 33, 242–253. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sy, S.A.; Mokaddem, L. Energy poverty in developing countries: A review of the concept and its measurements. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 89, 102562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Tang, X.; Wei, Y. Research on Energy Poverty: Current Situation and Future Trend. China Soft Sci. 2015, 30, 58–71. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Olang, T.A.; Esteban, M.; Gasparatos, A. Lighting and cooking fuel choices of households in Kisumu City, Kenya: A multidimensional energy poverty perspective. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2018, 42, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiber, M.U.; Grimsby, L.K.; Aune, J.B. Reducing energy poverty through increasing choice of fuels and stoves in Kenya: Complementing the multiple fuel model. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2015, 27, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Malakar, Y.; Davies, P.J. Multi-scalar energy transitions in rural households: Distributed photovoltaics as a circuit breaker to the energy poverty cycle in India. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandker, S.R.; Barnes, D.F.; Samad, H.A. Are the energy poor also income poor? Evidence from India. Energy Policy 2012, 47, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Tiwary, N. Role of Social Enterprises in Addressing Energy Poverty: Making the Case for Refined Understanding through Theory of Co-Production of Knowledge and Theory of Social Capital. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, J.; Bernal, E.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, P. Towards Use of Cleaner Fuels in Urban and Rural Households in Colombia: Empirical Evidence from 2010 to 2016. Energy J. 2021, 42, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Dong, K.; Dong, X.; Shahbaz, M. How renewable energy alleviate energy poverty? A global analysis. Renew. Energy 2022, 186, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B. Possible Impact and Enlightenment of energy crisis in Europe. People’s Trib. 2022, 106–110. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Llera-Sastresa, E.; Scarpellini, S.; Rivera-Torres, P.; Aranda, J.; Zabalza-Bribián, I.; Aranda-Usón, A. Energy Vulnerability Composite Index in Social Housing, from a Household Energy Poverty Perspective. Sustainability 2017, 9, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.P.; Nasir, M.A.J.E.E. An inquiry into the nexus between energy poverty and income inequality in the light of global evidence. Energy Econ. 2021, 99, 105289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okushima, S. Energy poor need more energy, but do they need more carbon? Evaluation of people’s basic carbon needs. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 187, 107081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papada, L.; Kaliampakos, D. Development of vulnerability index for energy poverty. Energy Build. 2019, 183, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okushima, S.J.E. Gauging energy poverty: A multidimensional approach. Energy 2017, 137, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambawale, M.J.; Sovacool, B.K.J.E. Energy Security: Insights from a ten country comparison. Energy Environ. 2012, 23, 559–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Mukherjee, I. Conceptualizing and measuring energy security: A synthesized approach. Energy 2011, 36, 5343–5355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Heffron, R.J.; McCauley, D.; Goldthau, A. Energy decisions reframed as justice and ethical concerns. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Cooper, C.; Bazilian, M.; Johnson, K.; Zoppo, D.; Clarke, S.; Eidsness, J.; Crafton, M.; Velumail, T.; Raza, H.A. What moves and works: Broadening the consideration of energy poverty. Energy Policy 2012, 42, 715–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzarovski, S.; Thomson, H.; Cornelis, M. Confronting Energy Poverty in Europe: A Research and Policy Agenda. Energies 2021, 14, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damigos, D.; Kaliampakou, C.; Balaskas, A.; Papada, L. Does Energy Poverty Affect Energy Efficiency Investment Decisions? First Evidence from a Stated Choice Experiment. Energies 2021, 14, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaworyi Churchill, S.; Smyth, R.; Farrell, L. Fuel poverty and subjective wellbeing. Energy Econ. 2020, 86, 104650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaworyi Churchill, S.; Smyth, R. Energy poverty and health: Panel data evidence from Australia. Energy Econ. 2021, 97, 105219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafi, M.; Naseef, M.; Prasad, S. Multidimensional energy poverty and human capital development: Empirical evidence from India. Energy Econ. 2021, 101, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzarovski, S. Understanding energy poverty, vulnerability and justice. In Energy Poverty; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 9–39. [Google Scholar]

- Munro, P.G.; Schiffer, A. Ethnographies of electricity scarcity: Mobile phone charging spaces and the recrafting of energy poverty in Africa. Energy Build. 2019, 188–189, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tundys, B.; Bretyn, A.; Urbaniak, M. Energy Poverty and Sustainable Economic Development: An Exploration of Correlations and Interdependencies in European Countries. Energies 2021, 14, 7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, H.; Ma, Y.; Gao, Z.; Xue, B. Spatio-temporal variation and its influencing factors of rural energy poverty in China from 2000 to 2015. Geogr. Res. 2018, 37, 1115–1126. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG, Z.; SHU, H. Multidimensional Energy Poverty and Resident Health. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2020, 42, 16–26. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, B. Analysis of Energy and Poverty from the Perspective of Resident Welfare Changes. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2020, 37, 100–118. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Deng, M.; Cui, Z.; Cao, H. Impact of Energy Poverty on the Welfare of Residents and Its Mechanism: An Analysis Based on CGSS Data. China Soft Sci. 2020, 35, 143–163. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Dong, L. Research on the Effect of Financial Instruments on Energy Poverty Alleviation under the Background of Rural Revitalization Strategy—From the Perspective of Multidimensional Poverty. Acad. Res. 2022, 65, 91–97+2+178. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Xu, L. Technological Progress, Energy Poverty and Inclusive Green Development in China. J. Dalian Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci.) 2020, 41, 24–35. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nathan, H.S.K.; Hari, L. Towards a new approach in measuring energy poverty: Household level analysis of urban India. Energy Policy 2020, 140, 111397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.F.; Khandker, S.R.; Samad, H.A. Energy poverty in rural Bangladesh. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iddrisu, I.; Bhattacharyya, S.C.J.R.; Reviews, S.E. Sustainable Energy Development Index: A multi-dimensional indicator for measuring sustainable energy development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyprianou, I.; Serghides, D.K.; Varo, A.; Gouveia, J.P.; Kopeva, D.; Murauskaite, L. Energy poverty policies and measures in 5 EU countries: A comparative study. Energy Build. 2019, 196, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, P.; Phillips, J.; Purohit, P.J.I.B. The political economy of clean development in India: CDM and beyond. IDS Bull. 2011, 42, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simshauser, P. Fuel Poverty and the 2022 Energy Crisis. Aust. Econ. Rev. 2022, 55, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, K.; Ding, R.; Zhang, J.; Hao, Y. How do photovoltaic poverty alleviation projects relieve household energy poverty? Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2023, 118, 106514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).