Abstract

The adaptive evolution of cultural ecosystems is a distinctive process along the Silk Road in China, involving the transitional interaction of nature and culture. This study aims to provide theoretical recommendations for the management of cultural heritage sites along the Silk Road to assess the values and keep the balance between tourism development and cultural heritage protection. The paper focuses on 22 cultural sites in western China to study the adaptive evolution pattern of cultural landscapes along the Silk Road with landscape changes and the transmission patterns of modern cultural tourism. Based on relevant literature reviews, historical maps, and geomorphological maps, the factors influencing the evolution of the cultural ecosystem are explored. We present both the theoretical and managerial implications: the cultural heritage of the urban areas can vigorously develop the cultural tourism with a high degree of industrialization, suburban areas can boost up traditional tourism product routes. We also assume that the degree of development of cultural tourism depends on the cultural ecosystem service and the environmental status of the cultural landscape.

1. Introduction

In June 2014, China, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan jointly declared the “Silk Road: The Routes Network of Chang’an-Tianshan Corridor” in Qatar, which was successfully inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. The China section of the Silk Road application included 22 cultural sites in Henan, Shaanxi, Gansu, and the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. The folk art culture, folk customs, and religious beliefs formed in the natural environment of the area where these cultural relics are located are different, but there is a certain degree of correlation and inheritance. The natural landforms along the Silk Road are diverse, ranging from the Yellow River Alluvial Plain, Guanzhong Plain, Loess Plateau, Qinling Mountains, Hexi Corridor, Kunlun Mountains to Xinjiang Tianshan Mountains, Tarim Basin, Taklimakan Desert, and other types of landforms from east to west [1].

Nowadays, a major challenge is to maintain and enhance the contributions of landscapes to the quality of human life. The perceptions ofcultural ecosystem services(CES) provided by landscapes are likely to increase if landscape characteristics are attached more closely to functions in order to meet fundamental human needs [2]. With a continuous variety of cultural landscapes throughout history, the concept of cultural ecosystem services is increasingly important for measuring the tangible and intangible benefits that humans obtain from these ecosystems. One of the challenges of integrating a sense of place into the framework of ecosystem services is that it is not linked to abstract notions of ecosystems but tied to perceived landscape features such as mountains, rivers, and land. Such features contribute to ongoing efforts for refining the definitions and standardizing assessments of cultural ecosystem services [1].

Cultural ecosystem services (CES), such as aesthetic and recreational enjoyment, as well as a sense of place and local identity, play an important role in the contribution of landscapes to human well-being. Cultural heritage, social, and spiritual values were particularly attached to landscapes with wood, pastures, and grasslands, as well as urban features and infrastructures, i.e., to more anthropogenic landscapes. A positive though weak relationship was found between landscape diversity and cultural ecosystem service diversity [3].

The Silk Road’s cultural ecosystem service is a diversified way of life for different ethnic groups in a special ecological environment, including the individual characteristics of national culture formed by the specific ecological environment as well as the regional cultural characteristics embodied by the cultural relic sites inherited by people in a specific region over a long period of time. Based on the historical changes in cultural ecology in western China, this paper studies the impact of cultural tourism development on cultural heritage sites. With the rapid development of urbanization in China, the regional cultural ecosystem has become extremely fragile. Cultural heritage is a concentrated embodiment of the cultural ecosystem along the Silk Road, and whether or not the protection and utilization of cultural heritage can be coordinated with the regional cultural ecosystem is a key issue for the sustainable development of the Silk Road.

The main purpose of studying this issue is to suggest ways of protecting cultural heritage and also investigate the cultural ecosystem environment. Moreover, the paper emphasizes the need to create various forms of sustainable cultural heritage that meet modern human living needs. It is necessary to make it possible for future generations to trace back the origin of cultural heritage, as well as to increase the cultural ecosystem service for the modern life of human beings. Taking the adaptive evolution of the cultural ecosystem of the Silk Road in China as a case study, the approach of adaptive evolution very well suits explaining historic processes based on vivid and convincing evidence. As a result of the research, theoretical recommendations that are based on cultural values and the balance between tourism development and cultural heritage protection were worked out.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

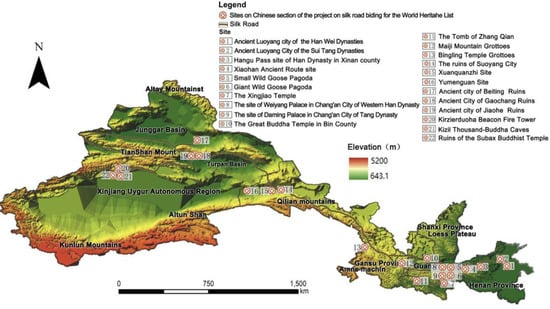

This paper focuses on the four major types of cultural heritage sites in the Chinese section of the Silk Road inscription and studies the cultural landscape changes as well as the inheritance methods of modern cultural tourism in the regions. The four types of cultural sites include the sites of central cities (ancient capital sites, ancient frontier fortresses), religious communication sites (sites of Buddhist buildings, sites of cave temples), traffic and defense sites (traffic towns, passes, posthouses, beacon sites), and related sites (tombs), involving a total of 22 sites in four provinces and autonomous regions of China (see Table 1, Figure 1, and Figure 2).

Table 1.

The distribution of Silk Road world heritage sites in the Chinese section and development around.

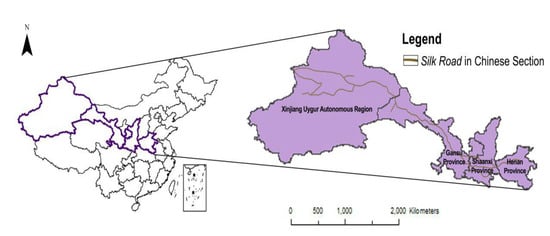

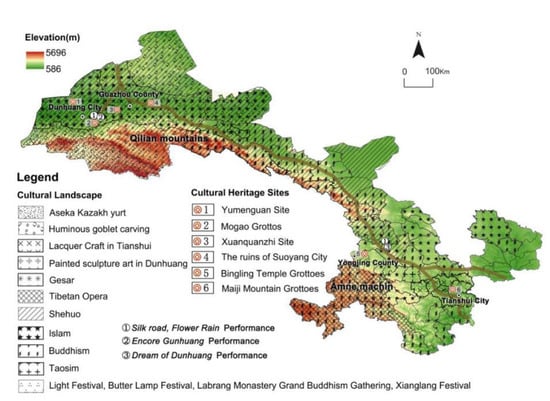

Figure 1.

Map of the Silk Road in Chinese section.

Figure 2.

The location of 22 cultural sites on the Chinese section of the Silk Road world heritage.

The ancient capital sites include the site of Luoyang City from the Eastern Han to Northern Wei dynasties, the site of Weiyang Palace in Chang’an City of the Western Han dynasty, the site of Daming Palace in Chang’an City of the Tang dynasty, and the site of Dingding Gate in Luoyang City of the Sui and Tang dynasties, all of which were political, economic, and cultural centers in ancient China [4]. As the dynasty capital of ancient China, these sites have a long history of continuity, and the relevance of historical events has a great impact on other local sites [3]. These ancient Chinese capitals on the Silk Road witnessed the spread of Silk Road culture and its influence on people's lifestyle, production, culture, and art. The ancient western capital site is located in the suburbs of Xi'an, where the cultural heritage is very rich and crowded. There are many scenic spots, historical sites, cultural landscapes, and heritage sites around the city, with outstanding cultural connotations, and 34 national key cultural relics protection units.

The ancient frontier fortresses include the site of Yar City, the site of Gocho City, and the site of Beiting City, all of which were political, economic, cultural, and military centers in the ancient Western region, as well as important transport centers along the Silk Road. The history of the ancient frontier fortress as a city-state can be traced back to the 5th century BC [5]. With the rise and fall of the Central Plains regime, these fortified cities alternately controlled the major transport routes. In the 14th century AD, they were gradually destroyed and abandoned by war, with the areas in the control of local governments [4]. The ruins are named “deserted cities” by the archaeologists. As important transportation hubs and frontier towns along the Silk Road to the west, the ancient cities witnessed the rise and fall of cultural civilization in the western regions and the opening of the Silk Road by the Central Plains dynasty, followed by trade exchanges and prosperity.

The three major religions, especially Buddhist culture, spread through the Western Regions to the Central Plains, as far as North Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asia, which had an important impact on Chinese culture. The Great Wild Goose Pagoda, the Small Wild Goose Pagoda, the Xingjiaosi Pagoda, and the Subash Buddhist Ruins are the main sites of Buddhist buildings along the Silk Road. The Subash Buddhist Temple was completely abandoned, and only ruins remained of it. Nowadays, there are monks and pilgrims living in the Da Ci'en Temple with the Great Wild Goose Pagoda and the Xingjiao Temple with the Xingjiaosi Pagoda. The incense is flourishing and temple fairs are frequent, which has a great influence on the daily lives of the surrounding residents. The temple buildings of the Jianfu Temple with the Small Wild Goose Pagoda as the core have been destroyed, and now the Xi'an Museum integrating gardens and cultural relic displays has been built with the Small Wild Goose Pagoda and Jianfu Temple as the core.

The Bin County Cave Temple, the Maijishan Cave Temple Complex, the Bingling Cave Temple Complex, and the Kizil Caves Temple Complex are all grotto temples of a certain scale along the Silk Road, recording the cultural exchanges between the Central Plains and the multi-ethnic west. Located near the capital Chang’an at the beginning of the Silk Road, the Bin County Cave Temple was surrounded by a rich cultural heritage, historical and cultural landscapes, and numerous relics of the Zhou, Qin, Han, and Tang dynasties. The temple of cultural connotations is very prominent and abundant. It is in such an area that Bin County Cave Temple was built due to the long-term development of the Silk Road, the widespread nature of Buddhist culture, and the development of statue carving skills. It reflected the spread of Buddhist sculpture art to the Guanzhong area as it was spreading eastward. At that time, the Buddhist worship of the people in the Weibei region was on the rise. Yongjing County, where the Bingling Cave Temple Complex is located, has rich prehistoric cultural sites and primitive features. At present, except for the fact that there are still lamas living in Bingling Cave Temple, which has a profound impact on the lives of local residents, other cave temples have only left an abundance of grotto statues and the temples have been abandoned.

The traffic and defense sites include the site of Han’gu Pass of the Han dynasty in Xin’an County, the site of Shihao Section of the Xiaohan Ancient Route, the site of Suoyang City, the site of Xuanquan Posthouse, the site of Yumen Pass, and the Kizilgaha Beacon Tower. The cultural heritage of Gansu Province, located halfway between the interior and the border, has a distinct line of transition and integration, richer in content and deeper in meaning. There are many military support facilities preserved, such as post stations, passes, transportation towns, etc., [6].

2.2. The Conceptual Framework and Literature Review

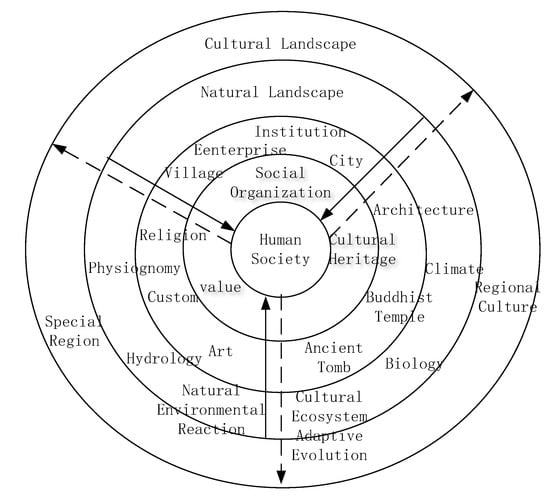

The concept of a cultural ecosystem was first proposed by the American anthropologist Steward, and Sahlins and Service defined cultural ecology in more detail [7]. The term “ecology” is originally a biological concept that refers to the unity of the interaction between biological communities and their geographical environment [8]. The American anthropologist Steward introduced the concept of "ecology" into the field of cultural anthropology and proposed the theory of "cultural ecology", asserting that culture is not a direct product of economic activity and that there are a variety of complex variables between them. The influence of natural conditions such as mountains, rivers and oceans, places of residence of various ethnic groups, the environment, old social ideas, new ideas that prevail in real life, specific trends in the development of society and communities, etc., and unique occasions and situations for emergence and development of culture [9]. Therefore, the development of human culture involves the whole process of interaction between culture and environment [8]. As interdependent dynamic ecosystems, the interactions between these parts rely upon the ways in which cultural activities are structured, distributed, received, and sustained [10]. The first nature is regarded as the natural ecological environment. Unlike the first nature, the cultural environment itself, which is regarded as the second nature, is the product of human society. For production and living needs, humans gradually transform and adapt to nature, and then the cultural landscape comes into being, demonstrating unique social phenomena [11]. The cultural ecosystem plays an important role in maintaining social succession and stability (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cultural ecosystem linked to cultural landscape and natural landscape.

Similar to natural ecology, cultural ecology is a corresponding concept. If all parts of human culture are regarded as an interactive whole, the various states of survival, transmission, and development of human social culture that correspond to natural ecology are the coupling of culture and environment, which is a kind of human cultural ecology [12]. Cultural ecology is a culture about ecology, that is, the achievements of human culture created by people in the process of acknowledging the environment and adapting to it [13]. Ecology is an important characteristic of culture. Cultural ecology is the historical and cultural foundation of social existence, and human activities make cultural ecology a dynamic system of development and change [14]. Once the cultural ecology is destroyed, the native culture will be eroded by cultural genetic mutation and cultural ecology imbalance, eventually leading to the native culture’s loss, degradation, and even forgetting [15].

As cultural ecological problems become more prominent in the development of cultural tourism, research begins to focus on the cultural ecological environment in the development of cultural tourism resources. Festival folk tourism, religious tourism, and heritage tourism are new forms of tourism; tourism projects based on strong ethnic colors, regional characteristics, and natural resources are constantly emerging in various places [16]. The negative development of modern tourism leads to the loss of cultural tourism environments and the destruction of cultural landscapes in many areas [17]. The importance of maintaining cultural ecological balance and cultural integrity is gradually being recognized by people [15]. Cultural ecology emphasizes the scientific development and protection of cultural resources, and the protection of cultural diversity and integrity in tourism development [18], in order to promote the balance of cultural ecology, cultural inheritance, and sustainable development of tourism [19].

The cultural ecosystem is a dynamic system formed by the interaction between the cultural system and ecological environment system [20]. It includes not only the relationship between culture and environment from the perspective of cultural anthropology but also the relationship between cultural forms from the perspective of cultural philosophy [21]. During the 1980s and 1990s, many domestic scholars, such as Lv L. [22], Jiao Y.M. [5], and Huang Z. [23], systematically interpreted the connotation of cultural ecology and cultural ecosystem from multiple disciplines and angles. Cultural ecology is dynamic, moving between equilibrium and imbalance, which is a dynamic accumulation of historical processes [24]. The historical and cultural heritage of a particular region and the geographical ecological environment contribute to the formation of a specific cultural ecology [25]. Cultural ecology requires not only analyzing the environmental model affecting cultural development from the natural ecological environment factors, but also caring for the humanistic environment, that is, the horizontal communication of different cultures, and the resulting cultural alienation and changes [26]. Therefore, in a broad sense, the cultural ecosystem evolves with changes in the natural environment, gradually adapts to the ecological environment, and eventually evolves into a new cultural ecology. For example, Maijishan Grottoes Temple and Binglin Grottoes Temple along the Silk Road were dug into the mountains and against the mountains. The architectural and Buddhist culture of the grottoes integrated the unique rocky features of the mountains and formed unique regional cultural features. The environmental pattern of Maijishan Grottoes Temple successfully makes use of the vertical sense of the mountain and the geomorphic features of layer upon layer with the unique charm of the Buddhist Mandala pattern [27]. Cultural ecology should grasp the intrinsic relationship between the cultural environment and cultural generation and systematically analyze and explain the cultural types and cultural patterns in the process of cultural adaptation to the environment [28].

Due to the close connection between natural and cultural landscapes along the Silk Road, many local governments are preparing cultural landscape corridor (CLC) proposals along China's Silk Road, which include many notable features of historical human activity and communication between different cultures [29]. In recent years, cultural ecological issues have become increasingly prominent in the massive development of cultural tourism attractions, and people have begun to realize the importance of protecting the cultural ecological balance and the continuity and integrity of national culture [30]. Cultural tourism research has shifted from focusing on the development and use of cultural tourism resources to the harmonious growth of the cultural and ecological environment, emphasizing the scientific development and protection of fragile cultural ecology as well as the protection of ethnic cultural diversity and cultural integrity in tourism development, promoting cultural ecological balance, the implementation of cultural heritage, and the development of sustainable tourism [31].

The cultural ecosystem in which human society is the main body contains not only the outermost natural world but also the cultural environment composed of values, social organization, the economic system, science, and technology [32]. Human society is constantly developing and changing under the dual environment of cultural environment as well as nature.

2.3. Methodology

Based on the local documents and literature reviews, the paper takes 22 cultural sites in Henan, Shaanxi, Gansu, and Xinjiang Uygur autonomous regions as examples, which are covered by the world heritage site “Silk Road: the road network of Chang’an—Tianshan corridor” on the Chinese section. There are many atlases to be referred to, such as the People's Republic of China National Historical Atlas [33], the Atlas of Humanities in Western China [34], and An overview of Chinese Regional Culture (Shaanxi volume, Henan volume, Gansu volume, Xinjiang volume [35,36,37,38]. In combination with the local records of various places, such as the Chinese religious research yearbook [39], Ethnography of China [40], China's ethnic statistics yearbook [41], and folk custom materials in Chinese local chronicles [42], a lot of data were collected on the natural environment and climate records, including historical and cultural inheritance pictures and the antiquities custodian interview. Through the comprehensive analysis and summary of all data, the rules and laws of the adaptive ecosystem evolution of cultural heritage sites along the Silk Road were explored.

In addition, we use the traditional analysis method of geography—the map expression method—to intuitively summarize the collected information, showing the effect of regional ecosystems on cultural systems. We observe the distribution of information points on the map to spatially analyze the region, studying the regularity of the distribution. The boundary and digital elevation model (DEM) elevation data of the five northwest provinces of China were added by using ArcGIS (Geographic Information System) software, and the data with clear locations such as world cultural heritage were searched by using the map coordinate picker in Baidu Maps, and then it was imported into ArcGIS. The characteristic culture as well as other contents of each region were then endowed with facet attributes for visualization research. Combined with literature, historical maps, and geomorphologic maps, this paper traces the relationship and evolution between cultural landscape and natural landscape, studying the adaptation of cultural ecological services together with the inheritance of cultural tourism. Finally, the paper reveals the relationship between cultural sites along the Silk Road, the surrounding environment, and the ecological evolution of China.

3. Results

3.1. Traditional Chinese Culture with Han Nationality as the Main Element

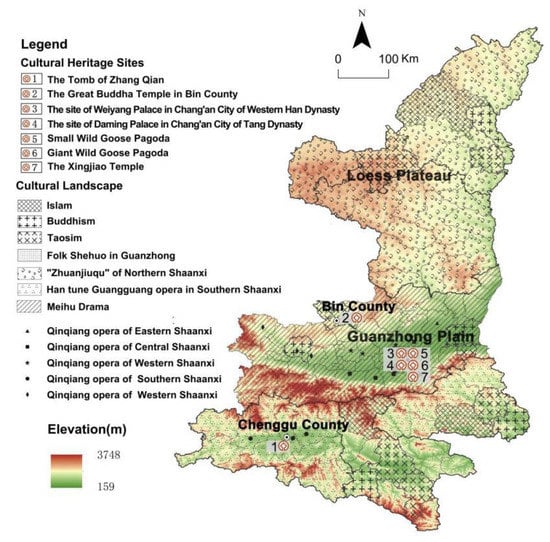

The Guanzhong-Zhongyuan Region, located in the middle reaches of the Yellow River, is the source of Chinese civilization and has a long history. A lot of dynasties had been established there. There has been a good ecological environment in history, and there is a rich farming culture belt in the north of China [43]. As the eastern starting point of the Silk Road, Eastern and Western cultures coexist and blend here. In the long impact of the natural and human environment, it has accumulated a rich cultural heritage and four ancient capital city sites have entered the World Heritage application list. The local culture shows the characteristics of diversity, inheritance, and localization. In the long-term process of the natural environment and historical changes, the characteristics of Han nationality as the main ethnic group came into being, which is the cultural integration of multi-ethnic, multi-religion, and exoticism. Some traditional folk customs and art culture, such as rural festivals, Shehuo performances, local opera, and culinary art, constantly blend with foreign culture, forming a regional culture featuring religion and folk art [40,44] (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The cultural heritage sites and cultural landscape in Guanzhong-Zhongyuan Region.

In long-term production and life, the working people in the Guanzhong-Zhongyuan Region, combined with the 24 solar terms and seasons, celebrated distinctive festivals, such as the Spring Festival, Lantern Festival, Dragon Boat Festival, Tomb-Sweeping Day, Mid-Autumn Festival, Double Ninth Festival, Chinese Valentine's Day, and Qiqiao Festival. These traditional folk festivals are associated with Chinese agricultural social culture with a long history. In addition, they express people’s worshipping of their ancestors and prayers for a peaceful and happy life. These festival customs spread to ethnic groups and areas, such as Korea, Japan, Vietnam, and Southeast Asia. People in these areas combined traditional Chinese holiday customs with local culture and created their own national festivals such as Japan's Daughter's Day and Obon Festival, Spring Festival, Dawang Festival, Dragon Boat Festival, Mid-Autumn Festival, and Korea's Double Ninth Festival [42,45].

Qinqiang Opera, Quzi Opera, and Shadow Play are the main folk drama forms in the Yellow River Basin, which have each formed unique local operas and cultures in their places [46]. These folk arts were inspired by local people’s longtime labor and daily lives and gradually evolved into forms of folk entertainment. Quzi Opera is widely spread in the five northwestern provinces of China. It is based on local life, work, love, marriages, and funerals and contains artistic components such as literature, music, dance, Quyi, and acrobatics. As one of the most popular folk cultures in Dunhuang, Dunhuang Quzi Opera absorbed the tunes of Shaanxi Opera, Meihu Opera, and Gansu Quzi Opera and was widely sung by local people and folk music troupes. Quzi Opera melts with various schools of art from the Central Plains, such as literature, music, dance, quyi, and acrobatics. Playing Quzi opera and folk tunes for Chinese and foreign tourists in Mogao Grottoes, Moon Spring, and other tourist attractions, as well as in farmyards and hotels nearby, has become a very popular performance [42,47].

Xinjiang Quzi Opera is a great fusion of various ethnic cultures, which broadly absorbs the singing, tunes, and Qupai in Northwest China and inland. It was introduced into the Xinjiang area and mixes the arts of ethnic groups, gradually creating a kind of local opera performed in Chinese with a unique local art style [48]. Quzi Opera in the Hami area also attracted many Uygur people, and even some Uygur actors performed Quzi Opera in Chinese. Weinan shadow play, which originated in the Han dynasty and has a history of more than 2000 years, was spread throughout the world along the Maritime Silk Road and the Overland Silk Road in the Yuan and Ming dynasties. It was the earliest national art treasure of Chinese Han culture going out to the world.

3.2. Transit Belt of Blending and Assimilation of Multiethnic Cultures for the Spread of Western Culture to the East

The Hexi Corridor is a long and narrow region, located at the middle node between the mainland and the border, connecting the Guanzhong-Zhongyuan Region and Western Regions from north to south and linking the Mongolia Plateau and Qinghai-Tibet Plateau from east to west. The convenience of transportation promotes the exchange, dissemination, integration, and development of multi-ethnic cultures. Hexi Corridor is an important post station for Buddhism to spread from west to east along the Silk Road [49]. The earliest Buddhist temple grottoes are preserved here, displaying the grotto art created by religious exchanges along the Silk Road. It has been further developed in combination with the Central Plains culture, and many folk arts and cultures are based on religious themes. In terms of cultural inheritance, Hexi culture lies between the Chinese culture in the Guanzhong-Zhongyuan Region and the minority culture in the Western Regions, and it is an intermediate transitional cultural belt where the two cultures blend, collide, and recombine with each other [50]. Because geographic barriers and a single channel of relief, in addition to folk customs, local culture, and art, work together in the region, the Hexi culture has created its own system, showing a trend towards diversity, transition, and integration of the cultures of the Central Plains and nomadic people [51]. It is a transitional area for the spread of Eastern and Western cultures, with rich cultural content and profound meaning (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The cultural heritage sites and cultural landscape in Hexi Corridor region.

Hexi Corridor is influenced by Buddhism's law of cause and effect, fortune telling, mystery legends, and superstitions; therefore, folk beliefs have been deeply integrated into the daily concepts and behaviors of ordinary residents as an ideology [52]. Impacted by the pluralism of religions, the folk customs and beliefs of the region tend to be complex. In addition, the long and narrow topography combined with land barriers caused the population of each area to seek their own gods, ancestors, and masters within their respective folk beliefs. The mutual influence of cultures among ethnic groups was weakened, while regional religious beliefs were basically stereotyped and solidified.

In the Hexi region, five ethnic religious and cultural communication areas in different regions were formed. The region includes grassland culture, Tibetan Buddhism communication area (Gannan Qinghai-Tibet area), farming culture and Han Buddhism grottoes art area (plain area west of Lanzhou), farming and commercial as well as Islamic culture communication area (Ningxia and Linxia area of Gansu); mountain farming culture and primitive religious culture communication area (Han-Tibetan area in Longnan mountain area); Zhou-Qin and Taoist culture communication area (Qingyang, Pingliang, and Tianshui area) [37,38].

The arts of Western regions and Europe, Central Asia, and South Asia, such as Brahmin, Lion Dance, Huteng Dance, etc., flowed through the Hexi region, creating elegant music and dance called Xilianzi, Ganzhouzi, and Basheng Ganzhou, which were introduced in Chang’an and integrated with “Qinhanji” in the Central Plains, then gradually developed into Yan court music during the Tang dynasty [49,53].

3.3. Ethnic Minority Regrouping Centered Around Islam

Xinjiang is a unique geographical and cultural unit because of its vast territory, diverse climate, geographical environment, and multi-ethnic settlements. Xinjiang has been an important core area of the Silk Road since ancient times. Here various religions, cultures, and arts intertwined, blended, developed, and came into being as a unique and diverse culture with historical, regional, and national characteristics. In this region, a living culture of different times was created and spread, including Western Buddhist culture, Uygur culture, Islamic culture, Silk Road culture, and the revolutionary red culture of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps [54]. The complex culture is the concentrated embodiment of the regional integration of multi-ethnic cultures in Xinjiang (see Figure 6).

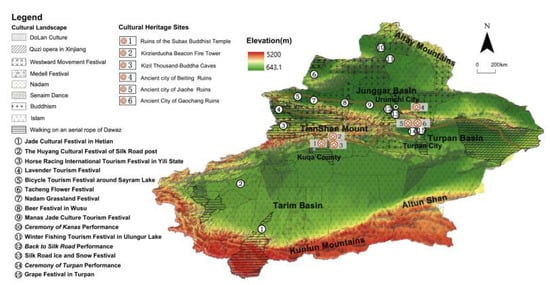

Figure 6.

The cultural heritage sites and cultural landscape in Xinjiang region.

The contact, conflict, exchange, and integration between the oasis farming culture in the southern foothills of the Tian Shan mountains and the prairie nomadic culture in the northern foot of the Tian Shan Mountain promoted the exchange of heterogeneous cultures and the urbanization from nomadic to sedentary culture [55]. In this process, Buddhism originated in India and spread to the Central Plains through the southern foothills of the Tianshan Mount and the Turpan Basin. The Spring Festival and Buddhist festivals every year prevailing in the Central Plains are also grand festivals of Han, Mongolia, Xibo, Manchu, Daur, and other ethnic groups in this region [56]. Each ethnic group still retains its own traditional festival celebrations. Medl Festival is the biggest temple fair of Mongolian Tibetan Buddhism. Westward Migration Festival is a traditional festival for the Xibo people to commemorate their ancestors’ westward migration. Over the years, the forms and ceremonies of celebrations at some national festivals have gradually changed. Nadam Congress traditionally held a large sacrificial activity of lamas burning incense, lighting lamps, and praying for gods, but now it has become an annual competitive entertainment activity for Mongolians. Islam has the greatest influence on the cultural life of most ethnic groups in Xinjiang, which is carried out by more than 10 ethnic groups such as the Uighurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, and Tajiks [12,40,41,42].

Xinjiang has formed an extremely unique regional ethnic culture due to its vast territory and the barrier of deserts and mountains. On both sides of the Yarkant River and in the vast grassland, wasteland, and the flourishing primitive populus euphratica forest, there is a unique “Dalan people” ethnic group mixture of local indigenous Uygur and foreign Mongolian nomads. They created the Dalan culture represented by “Dalan Muqami”, “Dalan Meshripi”, and “Dalan Peasant Painting” [57].

4. The Spatial Evolution of the Landscape and Cultural Tourism

4.1. Religious Festival

The Guanzhong-Zhongyang region has been a gathering place for religious and cultural exchange, including Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, and Christianity, on the Silk Road since ancient times. Buddhism was widespread in Japan, Korea, and other countries in Southeast Asia. The ancestral homes of seven of the nine major Buddhist schools remain completely intact in Xi’an, a city named Chang’an in ancient times, which was the birthplace of Buddhist culture in East Asia and Southeast Asia [39,58]. The Islamic customs of Muslim Lane in Xi'an City, the so-called Seven Temples and Thirteen Squares, have been well preserved since the Tang and Song dynasties, which is a witness to the cultural mingling of the Silk Road [59]. Xi’an Guangren Temple is the only main sermon place of the Green Tara Buddha Ceremony in China and the only temple of the Tibetan Gelug sect in Shaanxi Province. Since the Qing dynasty, it had been a palace for lamas and Panchen from the northwest of China, Tibet, Qinghai, and other places to Beijing, who paid homage to the emperor while traveling through Shaanxi Province. Every year on the eighth day of the first lunar month, tens of thousands of butter lamps in Guangren Temple are lit to celebrate the Lighting Festival, praying for peace and good luck [18].

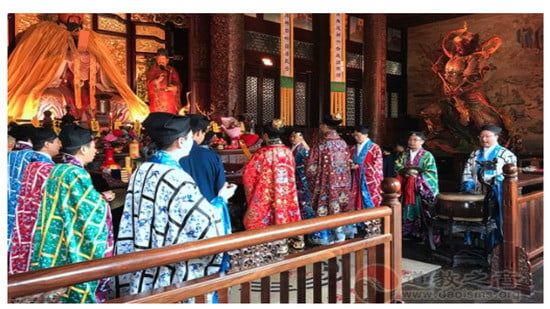

A large number of well-preserved religious buildings, Taoist temples located on the mountains of Taibai, Zhongnan, Shaohua, and Huashan in Shaanxi Province, are integrated into the daily lives of the surrounding people, becoming the unique folk customs and cultural characteristics of the Guanzhong region. Worshipping the god Chenghuang from Taoists spread in the west from the Guanzhong-zhongyuan region to the area of the Hexi corridor and east to Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, and south to Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, and other countries. Every county and city in ancient China has a Chenghuang temple, where people worship the city god to bless their lives with happiness. The temple with a history of more than 600 years in Xi’an, called Du Chenghuang Temple, once promoted the rite as a part of a nationwide sacrifice during the Ming dynasty [39,42,60]. Nowadays, the commercial events and the religious ceremonies held in the center of the Du Chenghuang Temple every year are becoming more attractive. In the Cheng-huang theater, people can watch various traditional performances, such as Chang’an drums, Qinqiang opera, and acrobatics; they can also taste traditional flavors and worship the Chenghuang gods to pray for their wealth and security (see Figure 7). The Du Chenghuang Temple is becoming a paradise for rest and tranquility for today’s youth [42,61].

Figure 7.

The ritual of Buddhism gathering held in Xi’an Du Cheng Huang Temple.

Buddhism and Taoism were very popular in the Hexi Corridor region; and along the Silk Road, many religious beliefs such as Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and Islam were introduced to China [62]. Religious events have a great influence on people's lives in the Hexi Corridor region. There are nine types of temple fairs associated with Buddhist beliefs, festivals, and twenty-six types of temple fairs associated with Taoist beliefs and festivals, as well as some festivals associated with Islam. Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha are common holidays shared by ethnic groups who believe in Islam in northwest China [39,63].

4.2. The Annual Meetings of the Traditional Custom

The Han and other ethnic groups of Tibetans, Hui, Tu, Sala, and Mongols in northwest China, including Qinghai Province, Gansu Province, Ningxia Autonomous Region, and Xinjiang Autonomous Region, composed a unique folk song called Hua'er during their long-term agricultural labor and mountain freight transportation. The lyrics are very numerous and complicated with the traditional melody [64]. The Hua'er has been formed by many different schools and artistic styles. Every year, the Hua'er concert is given, and the singers come from five provinces (regions) in the northwest of China. The largest and most influential Hua'er concerts are held on Laoye Mountain in Qinghai Province and Lianhua Mountain in Gansu Province. Songmingyan Forest Park, where Hua’er’s annual concert takes place, is the birthplace of Hezhou Hua'er County and is regarded as the base of Hua'er’s Chinese heritage. It was ranked first on the National List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2006 [65]. During the festival of the Hua'er concert, tens of thousands of villagers converge on the mountain and participate spontaneously in a song meeting. Singing from all sides spreads over the mountain and is permeated with joy. A favorable natural state, combining the singing of folk songs in the choir, constitutes a good cultural ecosystem.

In Doumen Town, Chang’an County, Xi'an, tens of thousands of pilgrims worship stone images of the shepherdess and the weaver on the first and fifteenth days of the lunar calendar of each month, as well as on the seventeenth day of the lunar January and 7 July each year. In history, Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty trained the navy following the star map of the Milky Way, with the left side of the cowherd star and the right side of the weaver star. Then the stone carvings, which are the biggest remaining from the Han dynasty in China, were set up on both sides of the Kunming Lake in Xi'an(see Figure 8). For a long time, the cowherd and the weaver were regarded as deities by the local people, and the two stone carvings were honored as “stony deity father” and “stony deity mother” [36,42]. In the middle of the Tang dynasty, a temple was built to worship, and there is still an endless stream of pilgrims here. In addition to oral legends, there are various folk arts about the two deities, as well as ballads, clappers, shadow puppets. In this temple, people can see Qin opera, engage in paper-cutting, and other folk customs such as weddings, funerals, and praying [66]. Until now, some local traditional large temple fairs are preserved on the 16th and 17th lunar January, and 7th lunar July, as well as a ritual of worshiping two deities on the 1st and 15th of each lunar month. Typically, the temple fair in Doumen Town lasts three to five days, and at its peak, it is attended by tens of thousands of people a day [67].

Figure 8.

The stone carvings of the shepherdess and the weaver in Doumen Town, Chang’an County.

4.3. Cultural Tourism and Festival Performances

The 1979 and 2008 Hexi-themed song and dance drama “Flower Rain of the Silk Road” on the theme of Hexi culture was presented at the opening ceremony of the first Silk Road International Cultural Exhibition (Dunhuang) in 2016 and attracted the attention of the whole world [68]. With the rapid tourism development of Gansu Province and Dunhuang City, Hexi Culture Silk Road tourism has built to a rousing climax. The large immersive live performance named “Elysium Dunhuang” is derived from the Dunhuang frescoes in Hot Spring Desert Town. The late-night landscape spectacle with high technology through multi-dimensional display, digital imaging, and dynamic compression, condenses the background of the Silk Road into the natural landscape connotation and a high level of artistic experience of cultural tourism. Some local classic dramas, such as Silk Road with Flower Rain and Dream of Dunhuang, are performed in main attractions, hotels, and theme parks.

The unique geographical environment creates an ethnic context for the distinctive regional features of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Some ethnic group festivals attract many tourists from all over the country and develop various tourism festivals to meet the tourists’ needs. Famous tourist festivals, such as the Grape Ceremony in Turpan, Jade Cultural Festival in Hetian, Silk Road Ice, and Snow Festival in Urumqi, have attracted a large number of domestic and foreign tourists every year [37,41].

5. Factors Influencing the Evolution of the Cultural Ecosystem of Western China

5.1. Changes of Natural Environment and Traffic Conditions Fundamentally Change the Historical Function of Cultural Sites

With an excellent geographical location and transportation position, the Silk Road cultural sites were brilliant and prosperous. However, with the increase in population, the expansion of arable land, and the deforestation of vegetation, the original balance of the ecosystem was destroyed. With river depletion and land desertification, the local ecological environment was becoming more fragile. The increasing deterioration of the ecological crisis has made human existence difficult. In addition to frequent wars, regime changes, and abandoned routes, exotic cultural fusion crises forced the indigenous population to leave their homelands [4,36]. Gradually, these former prosperous cities, roads, and religious sites that served as important functional places were discarded and eventually absorbed by the mighty Gobi Desert. Some cultural objects lost their former functions due to changing traffic conditions.

For example, the western Hexi Corridor, such as the place of Xuanquan Posthouse, Yumen Pass, and Yang Pass in Gansu Province, which is a typical desert oasis in ecological structure, is the only gateway from the Central Plains to the Western Regions. With the opening of the Silk Road and the introduction of Buddhism, the art of murals and statues in Dunhuang reached a very high artistic level and flourished in the Sui and Tang dynasties. After the Song and Yuan dynasties, with the eastward shift of state regimes, the Silk Road on land gradually declined. After Dunhuang was occupied by Turpan in the middle of the Ming dynasty, the Ming government ordered Jiayu Pass to be closed, the Kansai civilians migrated to the border, and the local administrative system was abandoned, which reduced this area to a desert [69].

The site of Beiting City, site of Yar City, and site of Gocho City flourished in the commercial civilization of the Silk Road one after another and became important towns on the caravan trade routes of the Silk Road. At the beginning of the Tang dynasty, they reached their peak. With the destruction caused by war and natural disasters, the climate and environment got worse, and then the cities were abandoned and eventually emptied. In their long history, these old cities became more and more dead with the transition of their natural ecological environment and cultural ecosystem [17,38].

5.2. The Decline in the Transmission and Dissemination of History and Culture Has Changed the Historical Status and Value of Cultural Sites

With the introduction of Buddhism into the Central Plains via the Western Regions, the Hexi Corridor, the Bin County Cave Temple, the Bingling Cave Temple Complex in Yongjing County, and the Maijishan Cave Temple Complex in Tianshui all became important religious sites in the heyday of Buddhist culture along the Silk Road. At the convergence of the major routes of communication between China and the West, Buddhist culture combined with the special geographical environment and geomorphological characteristics to create religious sites that integrated religious beliefs, multicultural art as well as commercial trade, etc., [37,39]. These cultural sites gradually fell into the wilderness with the decline of trade along the Silk Road and the gradual disappearance of Buddhist culture.

The Bin County Cave Temple in Shaanxi Province is located in the Jing River Valley of the Weibei Plain, which is an important location for land and water transport that connected the Central Plains, the Hexi Corridor to the north, and the Tianshan Mountains with the Seven Rivers region, the Silk Road, the Tea-Horse Road, as well as the Shaanxi-Shangxi Corridor to the south [70]. The temple was excavated at the foot of Qingliang Mountain, which is comprised of red sand and gravel. This mountain was surrounded by other mountains and water, creating a good environmental landscape. Both in terms of the ancient geomantic omen pattern and the modern landscape setting, the temple has preserved its historical surroundings and appearance. With the construction of the cave temple and the spread of Buddhist culture, people gathered in the temple, lived on the surrounding ground, and conceived various other folk art forms. Since the end of the Tang dynasty, the surrounding ecological environment has deteriorated with frequent wars and the migration of the capital city. There are large rocks exposed to the surface near the grottoes, which aggravate soil erosion; the area of vegetation was reduced; the carrying capacity of the farmland was reduced; the space available was narrow; and the land of the temple was constantly eroded. The Bin County Cave Temple finally lost its former glory, which led to the monks leaving and the temple becoming empty [70]. Over the course of a long period of social and historical development, the diverse cultural ecology changed, with religious culture no longer being the mainstream culture of the whole social life and gradually declining, while other diverse folk cultures enriched people’s lives.

5.3. The Interaction of Nature and Culture Over a Long Period of Historical Change to Form an Adaptive Cultural Ecology

Human culture has always interacted with nature and the changing environment. In the end, the former culture will gradually be replaced by a new culture that is more adaptable to the environment.

The Bingling Cave Temple Complex in Yongjing County, Gansu province, is located in the Central Plains, at the intersection of the Hexi Corridor, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, and an ancient ferry in the upper reaches of the Yellow River. The Silk Road, Tangfan ancient road, Qiangzhong Road, Daduobagu Road, and other transportation arteries interweave here. The water systems such as the Daxia River and Taohe River flow into the Yellow River from its vicinity. It has been a multi-ethnic settlement since ancient times. Influenced by the ancient minority nationalities such as Xianbei, Qiang, Dangxiang, Tubo, Uighur, Mongolia, etc., the style of Tibetan and Han in grottoes is very remarkable [71]. The terrain structure of Bingling Temple grottoes is a typical Danxia landscape, and the unique natural environment is in line with the site selection conditions of early Buddhism: “between mountains and hollows, sitting and meditating”. The natural, religious, and cultural landscapes blend with each other, while minority nationalities continuously migrate and mix, resulting in an important trade channel on the Silk Road. Buddhism and minority nationalities influenced the art and culture of the grottoes together [21,39]. This mixture of Chinese and Tibetan influences developed in the process of continuous integration and conflict. For a long time, it has also been the place where the beliefs of all ethnic groups compete. Because of their different religious beliefs, the winners often destroyed their opponents’ religious idols and set up their own national religious idols. Ethnic conflicts also destroyed the integrated cultural ecology [53,54]. The statues and grottoes of Bingling Cave Temple have left historical traces of destruction and reconstruction at different times. With the construction of the Liujiaxia reservoir and the rise of water levels, there is no longer much left of the once-thriving religious atmosphere that stood on the edge of the Yellow River [72].

Although the influence of Buddhism on people's lives is not as strong as before, the Tibetan Buddhism Festival is still a very grand and important religious ceremony. The surrounding Tibetan people have also changed the nomadic lifestyle of living by water and grass; after all, it has gradually settled down. The traditional diet and clothing culture have gradually integrated with modern life. The Tibetan residents now wear modern T-shirts with traditional Tibetan robes. Sports shoes and leather shoes have also replaced boots [73].

5.4. Economic Development Changes People's Customs and Traditional Culture

With the development of foreign exchange and the tourism economy, the traditional religious festivals as well as unique cultural customs on the western Silk Road have attracted a lot of people to visit and experience them. Influenced by modern lifestyles, some ethnic groups have gradually abandoned the strict and hierarchical atmosphere of their religious rituals. Instead, they have added a happier and family-friendly atmosphere. The integration of folk art customs with modern culture is more likely to conform to contemporary lifestyles. For example, the Tibetans hold the grand religious festival, Light Festival, to commemorate their religious master Tsongkhapa on October 25 of the Tibetan calendar every year. The complicated religious ceremony in the temple has been simplified. People use the prayer wheel, pray for blessings, lay butter flowers, and burn Yuangen lamps for Buddha. During the Light Festival, the Mongolians in Xinjiang also hold various recreational activities, including traditional horse racing, wrestling, archery, dance, etc., [39,40,47].

With the development of the social economy, some national festivals have gradually lost their original religious and traditional folk meaning, and the joyful festival atmosphere has become the mainstream of society. The lamp, as a symbol of family and reunion, is also a unique Chinese cultural symbol. Around the Spring Festival of 2018, the first lantern festival with a brand in China, the Overseas Chinese Town Zigong Lantern Festival, lit up the colorful and happy Chinese New Year in 12 cities, including Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Chongqing. With a history of more than 800 years, the Zigong Lantern Festival in Sichuan has a longstanding reputation. It integrates the cultural elements of the Chinese nation and has been promoted as the “Global Lantern Festival” with the approval of the Publicity Department of the Central Committee [42]. With the shining posture of the "Chinese Lantern", “Spring Festival Culture Going Global” has become an important project of the national plan. In the next five years, Zigong City will hold lantern fairs in 100 cities at home and abroad, promoting the development of Zigong lantern fairs into “global lantern fairs”. Today, 95% of the places with lantern festivals in the world are related to Zigong lamps, which have become a cultural brand for the globalization of Chinese folk culture [74].

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

In the case of Europe, adaptive cultural evolution was studied by Kandler, Laland, Shennon, and others. Their research has mainly focused on the mathematical simulation of historical processes. For example, Shennan [75] came to the conclusion that cultural change is a consequence of declining populations, whereas Kandler and Laland [76] focused on the interaction between innovation and cultural change. In their opinion, innovation in technology was the main driver behind cultural change. Our research differs from the above-mentioned ones by applying field study and descriptive analysis to historical processes. In the future, we plan to enhance this research by adding more statistical data and applying simulation models; however, for now, it is impossible to do that because of the lack of data and cooperation.

Based on this research, we can list the following theoretical implications:

Firstly, the types of heritage sites changed from the capital sites to the military defense sites from east to west. The 22 cultural sites of the Chinese section of the Silk Road are distributed from east to west with city sites, transportation, and religious sites. Caves and passes run through the entire Silk Road heritage corridor. The eastern sites include: Luoyang City from the Eastern Han to Northern Wei dynasties, Luoyang City of the Sui and Tang dynasties in Henan Province, the Weiyang Palace in Chang’an City of the Western Han dynasty, and the Daming Palace in Chang’an City of the Tang dynasty, which were the central cities of ancient China's politics, economy, and culture. The western sites include Suoyang City in Gansu Province, Gocho City, Yar City, and Beiting City in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, which were post stations or settlements for military defense and trade exchanges on the frontier.

Secondly, the function of the cultural landscape is followed by the change in the natural landscape. From east to west, the natural geomorphological and climatic types of the Silk Road World Heritage in the Chinese section gradually move from humid and semi-humid central plains to the Guanzhong Plain and Qinling Mountains, then further to arid and semi-arid desert steppes and oases, ending in arid deserts and sporadic oases. The types of Silk Road cultural landscapes change with the variety of natural landforms due to the long-term transitional factors of human history and the natural environment. Accordingly, the historical function of ancient city sites shifted from national capital to frontier fortress defense.

Thirdly, the type of heritage tourism changes from urban cultural tourism to natural ecotourism from east to west. Most of the heritage sites in the eastern part of the Silk Road are located in urban areas or suburbs near the city. The landscape types belong to urban–rural landscapes, and the heritage tourism type is close to urban cultural tourism. Western heritage sites are distributed far away from urban areas, even scattered in the Gobi Desert area. The landscape types belong to natural, primitive ecological landscapes, and the heritage tourism type tends to be natural eco-tourism.

In summary, the findings confirm that the change in the cultural ecosystem along the Silk Road is not only related to the function of the cultural landscape in the context of history and folk customs but is also influenced by the alteration of natural ecology. In addition, the results show that along the Silk Road from east to west the cultural tourism patterns change from modern people pursuing the historical capitals to exploring the genuine ecology with the evolution of cultural and natural landscapes. Modern people are gradually integrating into the ecological system of culture and nature through cultural tourism.

6.2. Managerial Implication

Following managerial implications were identified:

Firstly, cultural heritage in urban areas should be developed with a high degree of industrialization. This type of cultural heritage development suits the cultural heritage in Xi'an, which is the capital of ShaanxiProvince. The relatively mature tourist attractions are all based on cultural heritage, including building tourist squares, tourist attractions, tourist complexes, and landscape real estate with complete tourist infrastructure as well as the agglomeration of commercial blocks and residential and commercial buildings. On the background of creating a cultural space with prominent cultural themes, Xi'an City enriches the industrial layout with the combination of commercial elements and formats such as culture, leisure, and experience. It also introduces non-shopping leisure styles, and fashion industries such as theaters, art galleries, cinemas, exhibitions, museums, and creative block bars. The commercial goal is to create an experience space that integrates culture and artistry into leisure and connects traditional elements with contemporary cultural industries. This way of transforming heritage tourism into creative industries goes beyond the dilemma of the ticket economy, which relies solely on cultural relics and scenic spots. Through the development of entertainment and performances, night tour projects, festival activities, exhibitions, and other entertainment activities, Xi'an City is gaining great popularity and attracting a great flow of tourists, forming a hot tourist market atmosphere as well as strong consumption.

Secondly, cultural heritage in suburban or rural areas should be developed using traditional sightseeing cultural tourism routes. Usually, there is limited vehicular access to cultural sites in the suburbs or rural areas. Infrastructural conditions are underdeveloped. The separated single cultural heritage sites, which only serve as tourist visiting spots for a short stay along the tourist routes, have little relationship with other surrounding cultural and natural resources. There is no other tourism consumption except for the tickets. The tourists return to the central city for their consumption of food, shopping, accommodation, and other needs. This type of cultural heritage has little influence on the local economic development but, to some extent, can complement the tourism product of a central tourist city.

Thirdly, the cultural heritage in other regions should focus on the protective display of historical sites and relics. Other areas refer to nomadic areas, less populated areas, or no human areas. Due to the evolution of the historical and geographical environment, the cultural heritage in these areas has been buried in the vast historical dust of the desolate Gobi Desert. The remains are completely abandoned, and the surrounding areas are desolated, or there are small villages nearby. Nowadays, only the management institutions of cultural heritage maintain protective displays, and the conditions are not adequate to offer cultural tourism services and infrastructure. Most of the cultural sites in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region can be classified into this type. Far away from the central city, the cultural relics around Dunhuang City of Gansu Province are very fragile with the harsh local natural environment and backward economic development level. Only by taking perfect protection measures can these sites avoid more external interference and destruction.

6.3. Conclusion and Limitation In conclusion,

The level of development of cultural tourism depends on the environmental status of cultural ecosystem services and cultural landscapes; therefore, not all of the cultural heritage resources should be exploited as tourism assets. Some cultural sites with little infrastructure away from urban places should enhance heritage conservation and improve the natural environment rather than vigorously develop tourism infrastructure. Reducing the tourism impact on the sites may be the best way to protect these fragile cultural heritages. Heritage sites suitable for cultural tourism development should preserve the cultural ecosystem environment of the site as completely as possible, so that future generations can trace the origin of the site; meanwhile, modern people should better integrate with the cultural ecosystem, so that the heritage sites can become part of the lives of modern people.

Despite its revelation, our study has several limitations that may encourage future research. In terms of the case study, only 22 heritage sites in China were selected and verified for the adaptive evolution of cultural ecosystems along the Silk Road, and still, 11 heritage sites in Central Asian countries could not be traced due to data limitations. Subsequent studies could thus seek to obtain more comprehensive data so that our study can cover the whole section of the Silk Road. Additionally, from data analysis based on the synthesis of historical documents and map data in this paper, the research process of interview data with qualitative research was not included to further demonstrate the research conclusion. In a follow-up study, we will use the grounded theory approach to encode interview data and deduce, as well as summarize, the research questions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y. and B.S.; methodology, J.Y. and L.Y.; software, J.Y.; validation, B.S., M.B. and B.J.; formal analysis, J.Y. and B.J.; data curation, J.Y. and L.Y.; writing, J.Y., B.S., L.Y. and B.J., review and editing, M.B. and B.J.; visualization and check the references, J.Y. and L.Y.; supervision, J.Y. and B.S.; project administration, J.Y.; funding acquisition, J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology, belonging to “Road and Belt” Innovation Personnel Exchange Project named Promoting the International Impact of the Silk Road and Improving the Sustainable Development of Heritage Tourism (NO. DL2022040003L).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Wartmann, F.M.; Purves, R.S. Investigating Sense of Place as a Cultural Ecosystem Service in Different Landscapes through the Lens of Language. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 175, 169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, Y.H.; Yu, X.B.; Bakker, M.; DeGroot, R.; Carsjens, G.J.; Duan, H.L.; Huang, C. Analysis of the relationship between cross-cultural perceptions of landscapes and cultural ecosystem services in Genheyuan region, Northeast China. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 43, 101112. [Google Scholar]

- Oteros, R.E.; Martin-Lopez, B.; Fagerholm, N.; Bieling, C.; Plieninger, T. Using Social Media Photos to Explore the Relation between Cultural Ecosystem Services and Landscape Features Across Five European Sites. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 94, 74–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.Y.; Chen, Y.N. The Inherent Mechanism of the Rise and Fall of Cities and Towns along the Ancient Silk Road (China Section)and Its Enlightenment. J. Southwest Minzu Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2018, 39, 206–213. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Y.M. Study on the Cultural Ecology System of Hani Terraced Fields. Hum. Geogr. 1999, 14, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.Y. On the Silk Road Historical and Cultural Sites and its Concentration. Ningxia Soc. Sci. 2016, 1, 150–157. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, H. Evolution and Culture; Han, Jianjun; Shang, Geling, Translators; Zhejiang People’s Publishing House: Hangzhou, China, 1987; ISBN 3103-273. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, M.Q.; Anderson, E.N. An Introduction to Cultural Ecology; Altamira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 9781003135456. [Google Scholar]

- Steward, J.H. Theory of Culture Change: The Methodology of Multilinear Evolution; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1955; ISBN 9789573234722. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, R.; Booth-Kurpnieks, C.; Davies, K.; Delsante, I. Cultural Ecology and Cultural Critique. Arts 2019, 8, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioan, I.; Irina, S.; Valentina, S.I.; Daniela, Z. Perennial Values and Cultural Landscapes Resilience. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 122, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.L. The Decrease of Cultural Ecology. J. Peking Univ. 2001, 3, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.Q. Cultural Ecology; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2015; ISBN 9787516155516. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.C. Cultural Ecology: Background, Construction and Value. Seeker 2016, 3, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.Y.; Qiu, G.F.; Zeng, Z.J.; Xiao, M.X. Hakka Culture Tourism Development Basing on the Cultural Ecology. Econ. Geogr. 2012, 7, 172–176. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F. The Development Research of Mongolian Festival Folk and Grasssland Festival Folk Tourism. Master’s Thesis, Normal University, Hohhot, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ilies Alexandru; Hurley Peter Damian; Ilies Dorina Camelia; Baias Stefan. Tourist animation—A chance adding value to traditional heritage: Case study’s in the Land of Maramures (Romania). Revista de Etnografie și Folclor. J. Ethnogr. Folk. New Ser. 2017, 1–2, 131–151. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, W.; Ma, Y.F. Cultural Inheritance and Construction by Virtue of the Driving Force of Religious Tourism-A Case Study of Tibetan Buddhist Lotus Lantern Festival of Xi’an Guangren Temple. J. Tibet. Univ. 2014, 29, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, A.M.; Li, H.B. Preliminary Study on Cultural Ecotourism. Tour. Forum 2000, 3, 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ilieș, D.C.; Hodor, N.; Indrie, L.; Dejeu, P.; Ilieș, A.; Albu, A.; Caciora, T.; Ilieș, M.; Barbu-Tudoran, L.; Grama, V. Investigations of the Surface of Heritage Objects and Green Bioremediation: Case Study of Artefacts from Maramureş, Romania. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6643. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.W.; Long, Y.R. National Cultural Ecology of our Country in Recent Twenty Years. J. Dalian Natl. Univ. 2010, 12, 126–172. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, L.C. Cultural Ecology Thinking on the Coordinated Development of the Upper Reaches of the Yangtze River. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 1997, 1, 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z. On the Ecological Environment of National Culture. Guangxi Ethn. Stud. 1998, 2, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ilies, M.; Ilies, D.C.; Ilies, A.; Josan, I.; Ilies, G. The Gateway of Maramures Land. Geostrategical Implications in Space and Time. Ann.-Ann. Istrian Mediter. Stud. Ser. Hist. Sociol. 2010, 469–480. Available online: https://zdjp.si/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/ilIes-et-al_20_2.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2010).

- Wang, X.K.; Wang, Y.Y. Establishing Correction Mechanism of Scenic Spot Planning against the Incline of Urbanization Planning Based on the Two Scenic Spots. J. Guilin Inst. Tour. 2004, 5, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.G. Persisting in Advanced Cultural Direction and Developing China Nation Spirit are Necessary Demand of Cultural Ecology System’s Evolvement. J. Yunnan Norm. Univ. 2003, 5, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Yong, X.Q. Value and Preservation Strategy of the Environmental Landscape of Maijishan Grottoes. J. Tianjin Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2003, 1, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, L.N.; Chen, Y. Protection and Utilization of Intangible Cultural Heritage Based on Ecological Form Recognition—A Case Study of Shadow Play in Guanzhong. Forw. Position 2012, 23, 212–215. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.L.A. Philosophical Probe into Cultural Ecology. Master’s Thesis, Xinjiang University, Ürümqi, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ilies, A.; Dehoorne, O.; Ilies, D.C. The Cross-border Territorial System in Romanian-Ukrainian Carpathian Area. Elements, Mechanisms and Structures Generating Premises for an Integrated Cross-border Territorial System with Tourist Function. Carpathian J. Environ. Sciences. 2012, 7, 27–38. Available online: http//www.ubm.ro/sites/CJEES (accessed on 23 June 2012).

- Zhang, Y.W. Narrative Study of Dance Drama with Historical Subjects-Take Silk Road Theme Dance Drama as an Example. Master’s Thesis, Chinese National Academy of Arts, Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Safarov, B.; AlSmadi, H.M.; Buzrukova, M.; Janzakov, B.; Ilies, A.; Grama, V.; Ilies, D.C.; Vargáné, K.C.; Dávid, L.D. Forecasting the Volume of Tourism Services in Uzbekistan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Atlas Compilation Committee. People’s Republic of China National Historical Atlas; China Social Science Press& China Map Press: Beijing, China, 2014; ISBN 9787500469278. [Google Scholar]

- Editorial Department of Western China Humanistic Atlas. Atlas of Humanities in Western China; Xi’an Map Publishing House: Xi’an, China, 2012; ISBN 9787807488477. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.P.; Chen, J.Y.; Huang, L.Z. An overview of Chinese Regional Culture (Shaanxi Volume); Zhong Hua Book Company: Shanghai, China, 2013; ISBN 9787101089974. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.P.; Chen, J.Y. An overview of Chinese Regional Culture (Henan Volume); Zhong Hua Book Company: Shanghai, China, 2014; ISBN 9780150911172. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.Y.; Yuan, X.P. An overview of Chinese Regional Culture (Gansu Volume); Zhong Hua Book Company: Shanghai, China, 2013; ISBN 9788465731900. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.P.; Chen, J.Y. An overview of Chinese Regional Culture (Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Volume); Zhong Hua Book Company: Shanghai, China, 2014; ISBN 9787101089967. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.J. Annals of Chinese Religious Studies; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2020; ISBN 9787520356688. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.M. Ethnography of China; China Minzu University Press: Beijing, China, 2004; ISBN 9787810567640. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Economic Development, State Ethnic Affairs Commission. Statistical Yearbook of Chinese Nationalities 2020; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2021; ISBN 9787503795305. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.L.; Zhao, F. Compilation of Chinese Local Chronicles Folk Data (Northwest Volume); Beijing Library Press: Beijing, China, 1997; ISBN 9787501304479. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Y.Y.; Ren, Z.Y.; Yang, R. The Spatial-Temporal Analysis of Harmony Coefficient of Agricultural Eco-economic System in the Region of Guanzhong. Agric. Res. Arid. Areas 2010, 28, 243–250. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.J. Regional Comparison and Analysis of Shaanxi Folk Music Culture. J. Xi’an Conserv. Music. 2012, 31, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, Y.N. The Value and Propagation of Cultural of Tradition Chinese Festivals. Master’s Thesis, Ningbo University, Ningbo, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.W. Shaanxi Opera in Regional Cultural Ecology. J. Xi’an Conserv. Music. 2012, 31, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H. On Dunhuang QuziOpera. J. Shihezi Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2018, 5, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Jiang, K.L. The Formation and Development of Xinjiang Quzi Performances. J. Xinjiang Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2018, 46, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hai, B. The Formation of the Regional Characteristics of Buddhist Culture in Hexi Corridor--From the Perspective of the Silk Road. World Relig. Cult. 2019, 6, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.R. The Cultural Conflict, Exchange and Fusion of Multi-nationality in the Hexi Corridor. J. Chin. Hist. Geogr. 2006, 3, 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.Y. Study on the Interaction of Multi-ethnic Cultures in Hexi Corridor. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, W.B. A Probe into the Model of Multicultural Symbiosis and Harmonious Development of Ethnic Relations in Hexi Corridor. J. Ethn. Cult. 2019, 11, 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.H. The Culture of the Western Regions Spread to the East and Flourished the Culture of the Central Plains. Hist. Geogr. Rev. North-West China 1996, 2, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, W.Q. The Blending of Xinjiang’s Multi-religious Culture from the Perspective of Chinese Culture. Sci. Atheism 2018, 5, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.L. Discussion on the Urban Construction in Northern Tianshan Area-From the Perspective of the Contradiction, Conflict, Communication, and Integration between Farming and Nomadic Cultures. West. Reg. Stud. 2020, 4, 94–105, 168. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, X.C. The First Introduction of Buddhism into Qiuci. J. Xinjiang Norm. Univ. (Ed. Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2010, 31, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Abibula, A. An Anthropological Study on “Dolan”: A Special Uygur Cultural Group. Doctoral Dissertation, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Z.Q. The Deep Development of Buddhist Cultural Tourism Resources in Xi’an under the Concept of Harmony. Soc. Sci. 2008, 10, 96–99. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, L. “Xi’an Huifang”: Cultural Pearl on the Silk Road. China Muslim 2017, 5, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Nan, H.G. Xi’an’ s capital Temple. Master’s Thesis, Central University for Nationalities, Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.T.; Tao, R.L. The Historical Evolution of the City God Temple in Xi’an. China Taoism 2013, 6, 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.J. Religious Transmission and Integration on the Silk Road. China Relig. 2014, 7, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.H. Viewing the Historical Evolution of Intangible Culture in Hexi Corridor from Literature. China Local Rec. 2007, 6, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L. Contemporary Variation of Hua’er Folk Songs-From the Perspective of Cultural Ecology. Gansu Soc. Sci. 2012, 4, 132–134, 142. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.H. The Challenge and Cultural Innovation Faced by “Huaer” from the Protection of Intangible Culture. J. Qinghai Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2010, 32, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, G.Z.; Fan, L.W. Textual Research on the Legend of Cowherd and Weaver Girl in Doumen, Chang’an and the Connotation of National Culture. Folk. Stud. 2008, 2, 212–230. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.Y. Protection and Utilization of Folk Belief Culture of Han Nationality—A study of the Belief of Niulang and Zhinv in Doumen, Xi’an. Master’s Thesis, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Di, H.W. Building a New “the Belt and Road” Culture—From the Dance Drama “Flower Rain of the Silk Road”. Henan Soc. Sci. 2016, 24, 18–23, 123. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, S.D. The Beacon and Flint of Dunhuang and the Changes of the Silk Road on Land. Gansu Soc. Sci. 2017, 5, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Han, W. A Brief Account of Grotto Temples in Shaanxi. Cult. Relics 1998, 3, 67–74, 99–100, 102–103. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.C.; Ma, Y.Y. Bingling Cave Temple and the Five Main Branches of Route on the Eastern End of the Old Silk Road. Dunhuang Res. 2010, 2, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.Q.; Zhang, H.Y.; Xu, J.L. Main Environmental Geological Problems in the Protection of Bingling Cave Temple. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 1996, 10, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.W. The Spread, Development and Decline of Tibetan Buddhism in Bingling Temple. Tibet. Stud. 2000, 1, 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Q. Folk Festivals and the Development of Cultural Industry—Taking the Development of Zigong Lantern Festival and Colorful Lantern Cultural Industry as an Example. Cult. Herit. 2011, 4, 130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Shennan, S.J. Demography and cultural innovation: A model and its implications for the emergence of modern human culture. Camb. Archaeol. J. 2001, 11, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandler, A.; Laland, K.N. An investigation of the relationship between innovation and cultural diversity. Theor. Popul. Biol. 2009, 76, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).