Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention of Youth for Agriculture Start-Up: An Integrated Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Role of the Theory of Planned Behavior on Shapero’s Entrepreneurial Event and Sustainable Entrepreneur Intention

2.2. The Role of Shapero’s Entrepreneurial Event on Sustainable Entrepreneur Intention

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Research Methods

3.2. Measurement Scale

3.3. Data Analysis and Hypothesis Testing

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Testing (Outer Model)

4.2. Assessment of Goodness-of-Fit

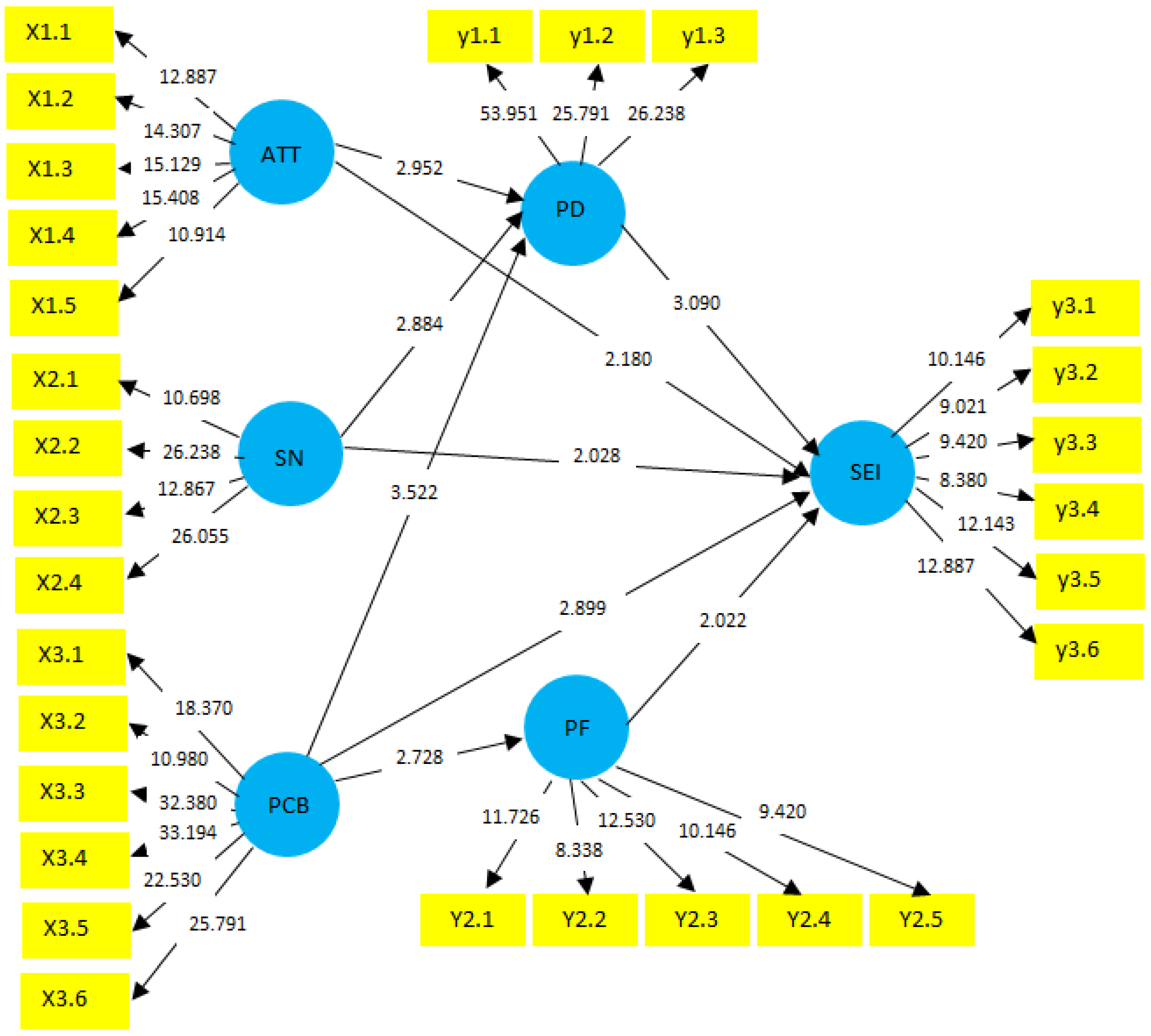

4.3. Test Results of the Partial Least Squares (PLS) Structural Model

4.4. Hypothesis Test

5. Discussion

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

7. Conclusions and Suggestions

7.1. Conclusions

7.2. Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ceresia, F.; Mendola, C. Entrepreneurial Self-Identity, Perceived Corruption, Exogenous and Endogenous Obstacles as Antecedents of Entrepreneurial Intention in Italy. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, B.; Schaeffer, P.R.; Vonortas, N.S.; Queiroz, S. Quality comes first: University-industry collaboration as a source of academic entrepreneurship in a developing country. J. Technol. Transf. 2018, 43, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Akhtar, F.; Das, N. Entrepreneurial intention among science & technology students in India: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 1013–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.; Morais, L.J.; Oliveira, J.; Oliveira, M.; Santos, T.; Sousa, M. The Impact of Gender on Entrepreneurial Intention in a Peripheral Region of Europe: A Multigroup Analysis. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamberidou, I. “Distinguished” women entrepreneurs in the digital economy and the multitasking whirlpool. J. Innov. Entrep. 2020, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, V.D.; Roman, A.; Tudose, M.B.; Cojocaru (Diaconescu), O.M. An Empirical Investigation of the Link between Entrepreneurship Performance and Economic Development: The Case of EU Countries. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Chandna, P.; Bhardwaj, A. Green supply chain management related performance indicators in agro industry: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 1194–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, N.; Shinnar, R.S.; Mirakzadeh, A.A.; Zarafshani, K. Cultural values and entrepreneurial intentions among agriculture students in Iran. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 1157–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cabrera, A.M.; Garcia-Soto, M.G.; Dias-Furtado, J. The individual’s perception of institutional environments and entrepreneurial motivation in developing economies: Evidence from Cape Verde. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2018, 21, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kallab, T.; Salloum, C. Educational Attainment, Financial Support and Job Creation across Lebanese Social Entrepreneurships. Entrep. Res. J. 2017, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, T.; Chauhan, G.S.; Saumya, S. Traversing the women entrepreneurship in South Asia: A journey of Indian start-ups through Lucite ceiling phenomenon. J. Enterprising Communities 2018, 12, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, H.A.; Everett, A.M. Migrant entrepreneurs from an advanced economy in a developing country: The case of Korean entrepreneurs in Malaysia. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2022, 14, 595–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbal, R.W. Social capital in Indonesia: Process to design. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. 2019, 8, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiadi, B.R.; Suparmin; Priyanto, S.; Setuju. A survey of engineering student’s in the creative industries sub-sectors. J. Adv. Res. Dyn. Control Syst. 2020, 12, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apriyeni, D.; Sjafrizal, S.; Jafrinur, J.; Noer, M. The Effect of Agglomeration on Profits and Price Efficiency in Laying Chicken Farming Enterprises in Payakumbuh Production Central Area of Lima Puluh Kota Regency, West Sumatera, Indonesia. J. Agric. Ext. 2019, 23, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candra, S.; Wiratama, I.N.A.D.; Rahmadi, M.A.; Cahyadi, V. Innovation process of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in greater Jakarta area (perspective from foodpreneurs). J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2022, 13, 542–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, F.; Antoni, D.; Suwarni, E. Mapping potential sectors based on financial and digital literacy of women entrepreneurs: A study of the developing economy. J. Gov. Regul. 2021, 10, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudayana, B. Involution in small-scale lava tour enterprises among people affected by the Mount Merapi eruption, Indonesia. Int. J. Tour. Anthropol. 2020, 8, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nindyasari, R.; Khotimah, T.; Ermawati, N. Decision support system to provide business feasibility analysis for batik entrepreneur in Lasem. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1943, 012106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devianto, D.; Maryati, S.; Rahman, H. Logistic Regression Model for Entrepreneurial Capability Factors in Tourism Development of the Rural Areas with Bayesian Inference Approach. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1940, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahidin, S. Legal perspective about the management of fishery and marine investment management in Indonesia. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2019, 10, 2146–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indriastuti, H.; Kasuma, J.; Za, S.Z.; Darma, D.C.; Sawangchai, A. Achieving marketing performance through acculturative product advantages: The case of sarong samarinda. Asian J. Bus. Account. 2020, 13, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astiana, M.; Malinda, M.; Nurbasari, A.; Margaretha, M. Entrepreneurship Education Increases Entrepreneurial Intention among Undergraduate Students. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 11, 995–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulus-Rødje, N.; Bjørn, P. Tech Public of Erosion: The Formation and Transformation of the Palestinian Tech Entrepreneurial Public. Comput. Support. Coop. Work. CSCW 2022, 31, 299–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukasiński, W.; Nigbor-Drozdz, A. Start-up and The Economy 4.0. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2022, 16, 749–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekanov, A. The Triple Helix in transition economies and Skolkovo: A Russian innovation ecosystem case. J. Evol. Stud. Bus. 2022, 7, 160–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumaidiyah, E.; Tripiawan, W.; Aurachman, R. Exploring the internal and external constraint of it business start up in Bandung, Indonesia. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2019, 8, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Suwarni; Noviantoro, R.; Fahlevi, M.; Nur Abdi, M. Start-up valuation by venture capitalists: An empirical study Indonesia firms. Int. J. Control Autom. 2020, 13, 785–796. [Google Scholar]

- Wit, B.; Dresler, P.; Surma-Syta, A. Innovation in Start-Up Business Model in Energy-Saving Solutions for Sustainable Development. Energies 2021, 14, 3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, E.H. Legitimacy building of digital platforms in the informal economy: Evidence from Indonesia. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 14, 1168–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisharyanto, E. Internet economy and start-up business development and policy in economic law perspectives. Int. J. Criminol. Sociol. 2021, 10, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.; Bentley, T. Early Evolution of an Innovation District: Origins and Evolution of MID and RMIT University’s Social Innovation Precinct in Melbourne’s City North. J. Evol. Stud. Bus. 2022, 7, 184–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.F.; Khan, K.I.; Saleem, S.; Rashid, T. What Factors Affect the Entrepreneurial Intention to Start-Ups? The Role of Entrepreneurial Skills, Propensity to Take Risks, and Innovativeness in Open Business Models. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.H.H.; Sehnem, S. Industry 4.0 and the Circular Economy: Integration Opportunities Generated by Start-ups. Logistics 2022, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaziz, S.; Oteshova, A.; Prodanova, N.; Savina, N.; Bokov, D.O. Digital economy and its role in the process of economic development. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues 2020, 9, 1225–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivathanu, B.; Pillai, R. An empirical study on entrepreneurial bricolage behavior for sustainable enterprise performance of start-ups: Evidence from an emerging economy. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 12, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rosa, I.; Gutiérrez-Taño, D.; García-Rodríguez, F.J. Social Entrepreneurial Intention and the Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Structural Model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arru, B. An integrative model for understanding the sustainable entrepreneurs’ behavioural intentions: An empirical study of the Italian context. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 3519–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, B. Entrepreneurial intentions research: A review and outlook. Int. Rev. Entrep. 2015, 13, 143–168. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gelderen, M.; Kautonen, T.; Fink, M. From Entrepreneurial Intentions to Actions: Self-Control and Action-Related Doubt, Fear, and Aversion. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaegel, C.; Koenig, M. Determinants of entrepreneurial intent: A meta-analytic test and integration of competing models. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 291–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Self-Regulation of attitudes, intentions & behaviour. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1992, 55, 178–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Consumer attitudes and behavior. In Handbook of Consumer Psychology; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sabah, S. Entrepreneurial Intention: Theory of planned behaviour and the moderation effect of start-up experience. In Entrepreneurship-Practice-Oriented Perspectives; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lortie, J.; Castogiovanni, G. The theory of planned behavior in entrepreneurship research: What we know and future directions. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 935–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosdi, S.A. Understanding Entrepreneurial Intention (EI): A Case Study of Lenggong Valley, Malaysia. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2015, 9, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ayalew, M.-M.; Zeleke, S.-A. Modeling the Impact of Entrepreneurial Attitude on Self-Employment Intention among Engineering Students in Ethiopia. J. Innov. Entrep. 2018, 7, 8–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaryab, A.; Saeed, U. Educating entrepreneurship: A tool to promote self employability. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2018, 35, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, N.; Mahmood, N.; Mehmood, H.S.; Rashid, O.; Liren, A. The Integrated Role of Personal Values and Theory of Planned Behavior to Form a Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, D.T.; Hung, N.T.; Phuong, N.T.C.; Loan, N.T.T.; Chong, S.C. Enterprise development fromstudents: The case of universities in Vietnam and the Philippines. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 18, 100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otache, I.; Umar, K.; Audu, Y.; Onalo, U. The effects of entrepreneurship education on students’ entrepreneurial intentions: A longitudinal approach. Educ. Train. 2019. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hueso, J.; Jaén, I.; Liñán, F. From personal values to entrepreneurial intentions: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, 27, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linan, F.; Chen, Y.W. Development and cross–cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Heory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C.; Rueda-Cantuche, J.M. Factors Affecting Entrepreneurial Intention Levels: A Role for Education. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2011, 7, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gelderen, M.; Brand, M.; van Praag, M.; Bodewes, W.; Poutsma, E.; van Gils, A. Explaining entrepreneurial intentions by means of the theory of planned behaviour. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 538–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veciana, J.M.; Aponte, M.; Urbano, D. University Students’ Attitudes towards Entrepreneurship: A Two Countries Comparison. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2005, 1, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Rodríguez, J.F.; Ulhøi, J.P.; Madsen, H. Corporate environmental sustainability in Danish SMEs: A longitudinal study of motivators, initiatives, and strategic effects. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agu, G.A. A survey of business and science students’ intentions to engage in sustainable entrepreneurship. Small Enterp. Res. 2021, 28, 206–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, I.; Latif, A.; Koe, W.L. SMEs’ Intention towards Sustainable Entrepreneurship. Eur. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2017, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorio, A.; Puumalainen, K.; Fellnhofer, K. Drivers of entrepreneurial intentions in sustainable entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 24, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Noboa, E. Social Entrepreneurship: How Intentions to Create a Social Venture are Formed. In Social Entrepreneurship; Mair, J., Robinson, J., Hockerts, K., Eds.; Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Schaper, M.T. Introduction: The essence of ecopreneurship. Greener Manag. Int. 2002, 38, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Argade, P.; Barkemeyer, R.; Salignac, F. Trends and patterns in sustainable entrepreneurship research: A bibliometric review and research agenda. J. Bus. Ventur. 2021, 36, 106092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Winn, M.I. Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Colmenares, L.M.; Reyes-Rodríguez, J.F. Sustainable entrepreneurial intentions: Exploration of a model based on the theory of planned behaviour among university students in north-east Colombia. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, J. The meaning of social entrepreneurship. In Case Studies in Social Entrepreneurship and Sustainability; 2001 Revision; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, N.F.; Carsrud, A.L. Entrepreneurial intentions: Applying the theory of planned behavior. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1993, 5, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, I.; Alalyani, W.R.; Thoudam, P.; Khan, R.; Saleem, I. The role of entrepreneurship education and inclination on the nexus of entrepreneurial motivation, individual entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial intention: Testing the model using moderated-mediation approach. J. Educ. Bus. 2021, 97, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoudam, P.; Anwar, I.; Bino, E.; Thoudam, M.; Chanu, A.M.; Saleem, I. Passionate, motivated and creative yet not starting up: A moderated-moderation approach with entrepreneurship education and fear of failure as moderators. Ind. High. Educ. 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Chowdhury, R.A.; Hoque, N.; Ahmad, A.; Mamun, A.; Uddin, M.N. Developing entrepreneurial intentions among business graduates of higher educational institutions through entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial passion: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Sun, J.; Bell, R. The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial mindset of college students in China: The mediating role of inspiration and the role of educational attributes. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Păunescu, C.; Popescu, M.C.; Duennweber, M. Factors determining desirability of entrepreneurship in Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, J.A.; Kobylinska, U.; García-Rodríguez, F.J.; Nazarko, L. Antecedents of entrepreneurial intention among young people: Model and regional evidence. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellnhofer, K.; Mueller, S. “I Want to Be Like You!”: The influence of role models on entrepreneurial intention. J. Enterprising Cult. 2018, 26, 113–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almobaireek, W.N.; Manolova, T.S. Who Wants to Be an Entrepreneur? Entrepreneurial Intentions among Saudi University Students. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 4029–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jubari, I.; Hassan, A.; Liñán, F. Entrepreneurial intention among university students in Malaysia: Integrating self-determination theory and the theory of planned behavior. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 1323–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.S.; Salam, M.; Ur Rehman, S.; Fayolle, A.; Jaafar, N.; Ayupp, K. Impact of support from social network on entrepreneurial intention of fresh business graduates: A structural equation modelling approach. Educ. + Train. 2018, 60, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T.; van Gelderen, M.; Fink, M. Robustness of the theory of planned behavior in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriano, J.A.; Gorgievski, M.; Laguna, M.; Stephan, U.; Zarafshani, K. A cross-cultural approach to understanding entrepreneurial intention. J. Career Dev. 2012, 39, 162–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wach, K.; Wojciechowski, L. Entrepreneurial Intentions of Students in Poland in the View of Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behaviour. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2016, 4, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, W.S.; Lo, E.S.C. Cultural contingency in the cognitive model of entrepreneurial intention. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 147–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Montes Botella, J.L.; Lin-Lian, C. Entrepreneurial Intention of Chinese Students Studying at Universities in the Community of Madrid. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargani, G.R.; Zhou, D.; Raza, M.H.; Wei, Y. Sustainable entrepreneurship in the agriculture sector: The nexus of the triple bottom line measurement approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliedan, M.M.; Elshaer, I.A.; Alyahya, M.A.; Sobaih, A.E.E. Influences of University Education Support on Entrepreneurship Orientation and Entrepreneurship Intention: Application of Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.B. Explaining the intent to start a business among Saudi Arabian university students. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2016, 6, 345–353. [Google Scholar]

- Iakovleva, T.; Kolvereid, L.; Stephan, U. Entrepreneurial intentions in developing and developed countries. Educ. Train. 2011, 53, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lihua, D. An extended model of the theory of planned behavior: An empirical study of entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial behavior in college students. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, G.; Kha, K.L. Investigating the relationship between educational support and entrepreneurial intention in Vietnam: The mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Arias, A. Factors that influence the entrepreneurial intention of psychology students of the virtual modality. Retos 2022, 12, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Widayanto, L.D.; Soeharto, S.; Sudira, P.; Daryono, R.W.; Nurtanto, M. Implementation of the Education and Training Program seen from the CIPPO Perspective. J. Educ. Res. Eval. 2021, 5, 614–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalanon, P.; Chen, J.-S.; Le, T.-T.-Y. “Why Do We Buy Green Products?” An Extended Theory of the Planned Behavior Model for Green Product Purchase Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Huang, Y.; Huang, R.; Xie, G.; Cai, W. Factors Influencing Returning Migrants’ Entrepreneurship Intentions for Rural E-Commerce: An Empirical Investigation in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.L.; Wang, Y.Y.; Yang, Z.H.; Huang, D.; Weng, H.; Zeng, X.T. Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: What are they and which is better? Mil. Med. Res. 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharjya, D.P.; Kiruba, B.G.G. A rough set, formal concept analysis and SEM-PLS integrated approach towards sustainable wearable computing in the adoption of smartwatch. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2022, 33, 100647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G.; Paul, J. CB-SEM vs. PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Parvaiz, G.S.; Dedahanov, A.T.; Abdurazzakov, O.S.; Rakhmonov, D.A. The Impact of Technologies of Traceability and Transparency in Supply Chains. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Mas’od, A.; Sulaiman, Z. Moderating Effect of Collectivism on Chinese Consumers’ Intention to Adopt Electric Vehicles—An Adoption of VBN Framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Joseph, F.; Hult GT, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, B.S.; Fethi, A.; Djaoued, O.B. The influence of attitude, subjective norms and perceived behavior control on entrepreneurial intentions: Case of Algerian students. Am. J. Econ. 2017, 7, 274–282. [Google Scholar]

- Dinc, M.S.; Budic, S. The impact of personal attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control on entrepreneurial intentions of women. Eurasian J. Bus. Econ. 2016, 9, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayati, D.T.; Fazlurrahman, H.; Hadi, H.K.; Arifah, I.D.C. The effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention through planned behavioural control, subjective norm, and entrepreneurial attitude. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2021, 11, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoda, N.; Ahmad, N.; Gupta, S.L.; Alam, M.M.; Ahmad, I. Application of Entrepreneurial Intention Model in Comparative International Entrepreneurship Research: A Cross-Cultural Study of India and Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, I.; Goo, J. Pre-Entrepreneurs’ Perception of the Technology Regime and Their Entrepreneurial Intentions in Korean Service Sectors. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srimulyani, V.A.; Hermanto, Y.B. Impact of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial motivation on micro and small business success for food and beverage sector in east Java, Indonesia. Economies 2022, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondari, M.C. Is entrepreneurship education really needed?: Examining the antecedent of entrepreneurial career intention. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 115, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festa, G.; Elbahri, S.; Cuomo, M.T.; Ossorio, M.; Rossi, M. FinTech ecosystem as an influencer of young entrepreneurial intentions: Empirical findings from Tunisia. J. Intellect. Cap. 2022, 23, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueto, L.J.; Frisnedi AF, D.; Collera, R.B.; Batac KI, T.; Agaton, C.B. Digital Innovations in msmes during economic disruptions: Experiences and challenges of young entrepreneurs. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidduck, R.J.; Clark, D.R.; Busenitz, L.W. Revitalizing the ‘international’in international entrepreneurship: The promise of culture and cognition. In The International Dimension of Entrepreneurial Decision-Making; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 11–35. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics of Respondents | Frequency (Person) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Based on Gender | Man | 468 | 63.41% |

| Woman | 270 | 36.59% | |

| By Age | 19–24 | 386 | 52.30% |

| 25–30 | 262 | 35.50% | |

| 31–35 | 90 | 12.20% | |

| Based on Occupation | Student | 253 | 34.28% |

| Private employees | 107 | 14.50% | |

| Farmer | 186 | 25.20% | |

| Businessman | 146 | 19.78% | |

| Other | 46 | 6.23% | |

| Variables | Indicator | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude | Advantages of being an entrepreneur | [54] |

| Attractive career | ||

| Opportunity and resources | ||

| Satisfaction of being an entrepreneur | ||

| Various options | ||

| Subjective Norms | Parents | [54,81] |

| Siblings | ||

| Friends | ||

| Someone else who is important | ||

| Behavior Control | Start a firm and keep it working | [54] |

| Prepared to start a viable firm | ||

| Control the creation process | ||

| Necessary practical details | ||

| Develop an entrepreneurial project | ||

| High probability of succeeding | ||

| Perceived desirability | Love to start own business | [77] |

| Tense to start own business | ||

| Enthusiastic to start own business | ||

| Perceived feasibility | Easy to start own business | [77] |

| Successful have own business | ||

| Won’t be overworked | ||

| How to start a business | ||

| Sure about myself | ||

| Intentions | Ready to do anything | [54] |

| Professional goal | ||

| Every effort | ||

| Determined to create a firm | ||

| Seriously thought of starting a firm | ||

| Firm intention to start a firm |

| Latent variable | Indicator | Loading Factor | t statistics | AVE (> 0.5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | Advantages of being an entrepreneur | 0.838 | 20.205 | 0.750 |

| Attractive career | 0.900 | 37.767 | ||

| Opportunity and resources | 0.881 | 30.135 | ||

| Satisfaction of being an entrepreneur | 0.857 | 24.876 | ||

| Various options | 0.834 | 20.963 | ||

| Subjective Norms | Parents | 0.817 | 16.044 | 0.706 |

| Siblings | 0.892 | 45.796 | ||

| Friends | 0.897 | 35.329 | ||

| Someone else who is important | 0.745 | 14.231 | ||

| Behavior Control | Start a firm and keep it working | 0.900 | 44.252 | 0.814 |

| Prepared to start a viable firm | 0.879 | 15.881 | ||

| Control the creation process | 0.918 | 49.725 | ||

| Necessary practical details | 0.966 | 198.737 | ||

| Develop an entrepreneurial project | 0.889 | 27.328 | ||

| High probability of succeeding | 0.856 | 20.604 | ||

| Perceived desirability | Love to start own business | 0.734 | 12.557 | 0.745 |

| Tense to start own business | 0.919 | 58.115 | ||

| Enthusiastic to start own business | 0.948 | 107.907 | ||

| Perceived feasibility | Easy to start own business | 0.809 | 14.252 | 0.718 |

| Successful have own business | 0.879 | 15.881 | ||

| Won’t be overworked | 0.818 | 49.725 | ||

| How to start a business | 0.765 | 19.737 | ||

| Sure about myself | 0.819 | 17.385 | ||

| Intentions | Ready to do anything | 0.729 | 7.178 | 0.675 |

| Professional goal | 0.843 | 15.037 | ||

| Every effort | 0.835 | 13.593 | ||

| Determined to create a firm | 0.872 | 17.223 | ||

| Seriously thought of starting a firm | 0.796 | 16.329 | ||

| Firm intention to start a firm | 0.745 | 14.231 |

| Characteristics | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability |

|---|---|---|

| Intention | 0.838 | 0.892 |

| Perceived feasibility | 0.875 | 0.896 |

| Perceived desirability | 0.838 | 0.892 |

| Behavior Control | 0.954 | 0.963 |

| Subjective Norms | 0.863 | 0.905 |

| Attitude | 0.952 | 0.960 |

| Variables | R2 | Communalities |

|---|---|---|

| Intention | 0.664 | 0.527 |

| Perceived feasibility | 0.516 | |

| Perceived desirability | 0.520 | |

| Behavior Control | 0.669 | |

| Subjective Norms | 0.558 | |

| Attitude | 0.614 |

| Hypothesis | Path | t-value | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude -> Perceived Desirability | 0.056 | 2.952 | 0.015 |

| Subjective Norm -> Perceived Desirability | 0.105 | 2.884 | 0.035 |

| Behavior Control -> Perceived Desirability | 0.137 | 3.522 | 0.000 |

| Behavior Control -> Perceived Feasibility | 0.098 | 2.728 | 0.029 |

| Attitude -> Sustainable Entrepreneur Intention | 0.065 | 2.180 | 0.040 |

| Subjective Norm -> Sustainable Entrepreneur Intention | 0.043 | 2.028 | 0.018 |

| Behavior Control -> Sustainable Entrepreneur Intention | 0.206 | 2.899 | 0.021 |

| Perceived desirability -> Sustainable Entrepreneur Intention | 0.109 | 3.090 | 0.002 |

| Perceived feasibility -> Sustainable Entrepreneur Intention | 0.038 | 2.022 | 0.020 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lediana, E.; Perdana, T.; Deliana, Y.; Sendjaja, T.P. Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention of Youth for Agriculture Start-Up: An Integrated Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2326. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032326

Lediana E, Perdana T, Deliana Y, Sendjaja TP. Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention of Youth for Agriculture Start-Up: An Integrated Model. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2326. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032326

Chicago/Turabian StyleLediana, Elsy, Tomy Perdana, Yosini Deliana, and Tuhpawana P. Sendjaja. 2023. "Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention of Youth for Agriculture Start-Up: An Integrated Model" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2326. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032326

APA StyleLediana, E., Perdana, T., Deliana, Y., & Sendjaja, T. P. (2023). Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention of Youth for Agriculture Start-Up: An Integrated Model. Sustainability, 15(3), 2326. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032326