Social Capital—Can It Weaken the Influence of Abusive Supervision on Employee Behavior?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Abusive Supervision

2.2. Employee Silence

2.3. Service-Oriented Organization Citizenship Behavior (SOCB)

2.4. Social Capital

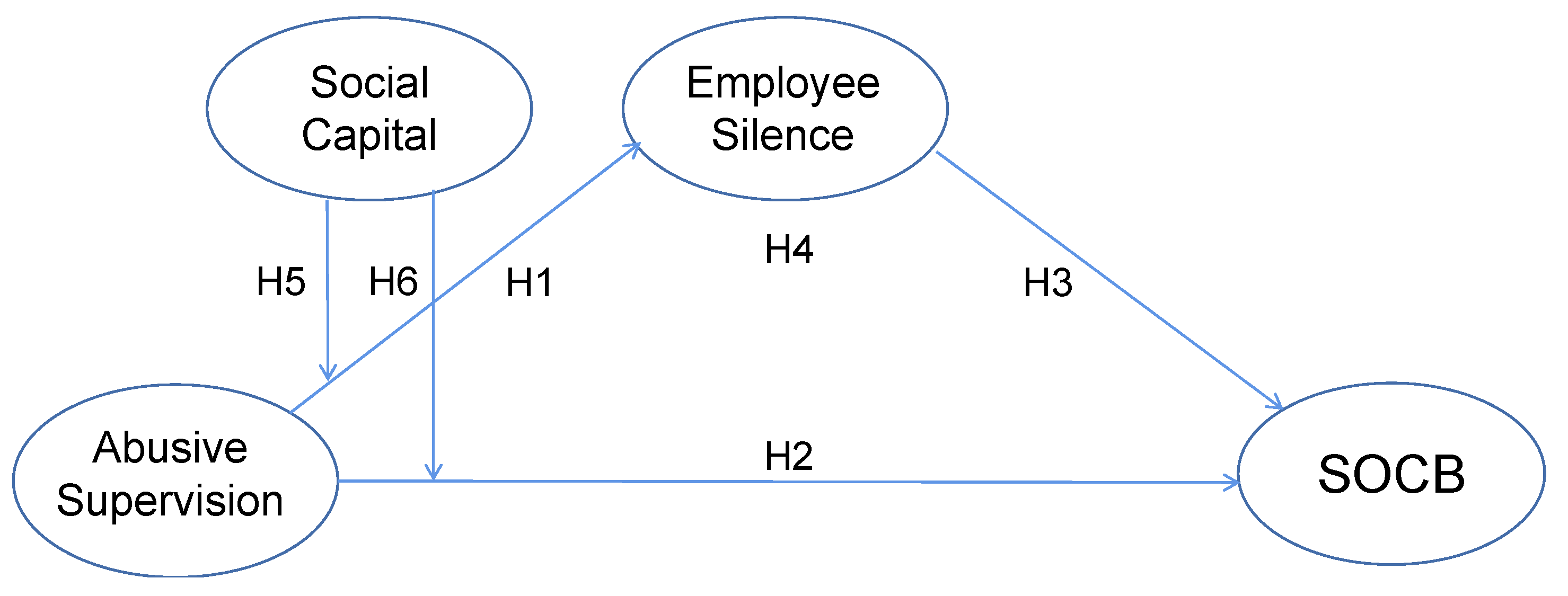

3. Theory and Hypotheses

3.1. Abusive Supervision and Employee Silence

3.2. Abusive Supervision and SOCB

3.3. Employee Silence and SOCB

3.4. Mediating Role of Employee Silence

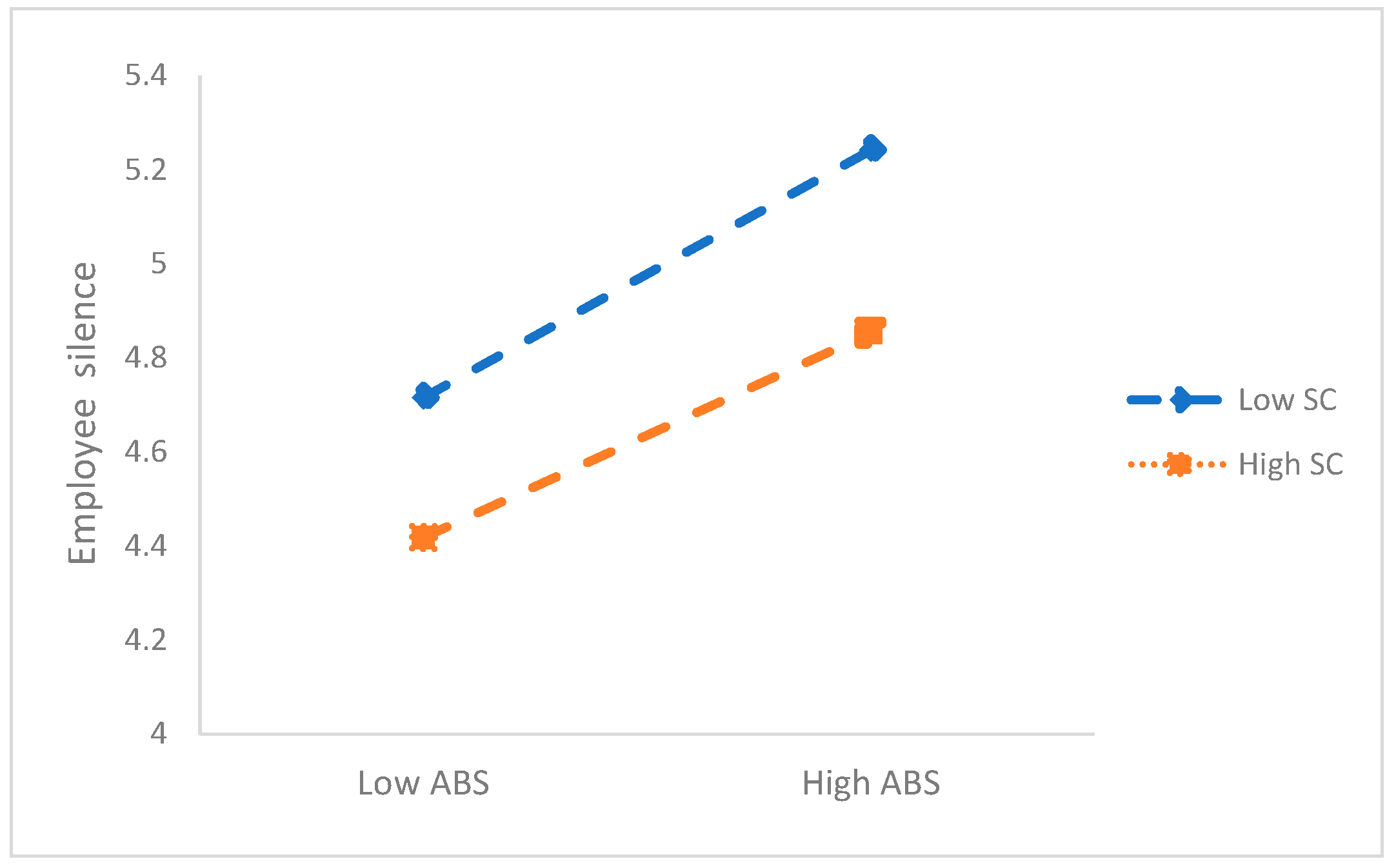

3.5. Moderating Role of Social Captial

4. Methodology

4.1. Measures

4.2. Sample and Procedures

4.3. Control Variable

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Analysis

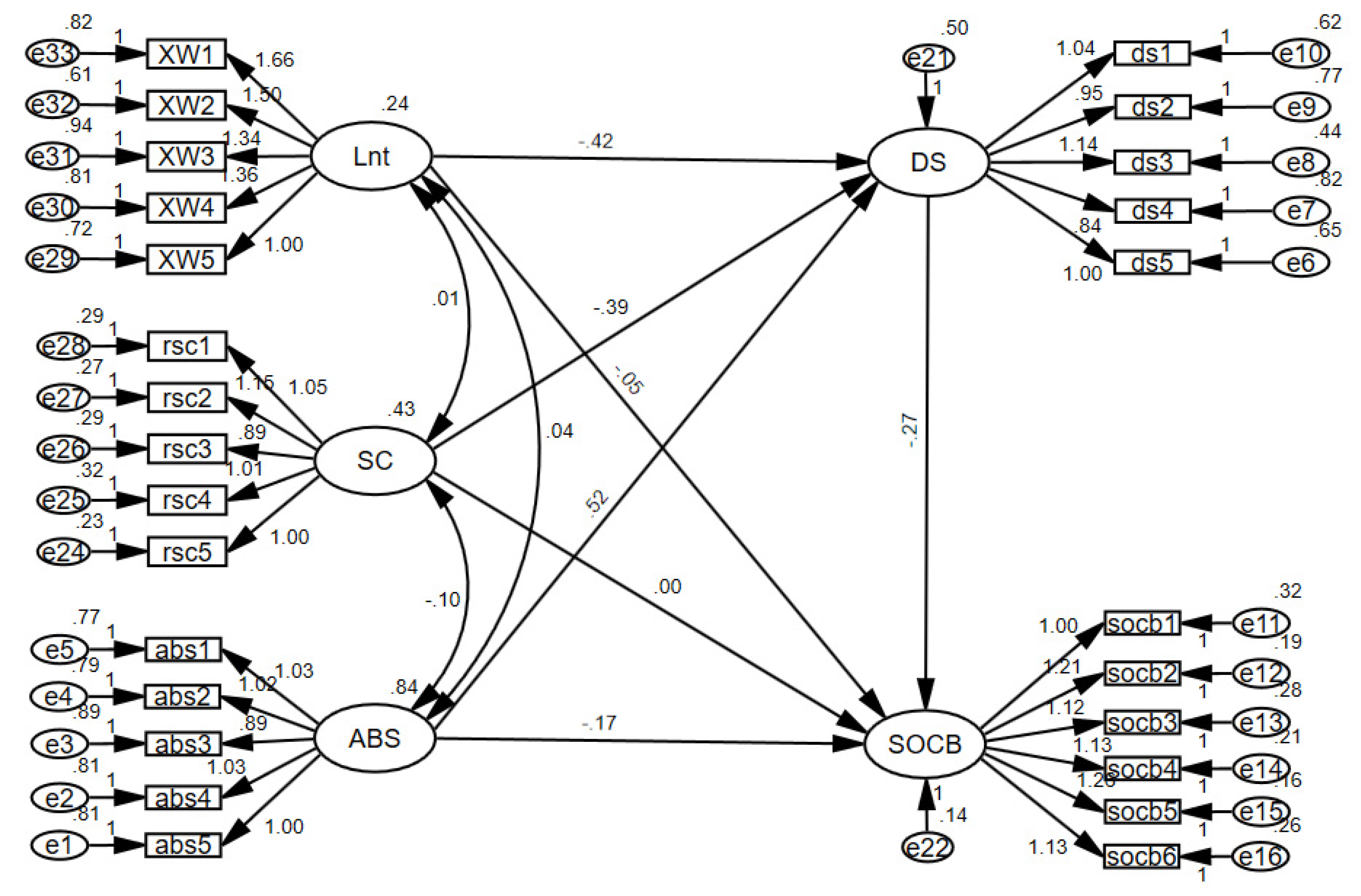

5.2. Model Validation Test

5.3. Hypotheses Testing

6. Conclusions

6.1. Discussion

6.2. Future Research and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Tourism Organization. New COVID-19 Surges Keep Travel Restrictions in Place [EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/new-covid-19-surges-keep-travel-restrictions-in-place (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- Jin, S.Y.; Gao, Y.Y.; Xiao, S.F. Corporate Governance Structure and Performance in the Tourism Industry in the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Empirical Study of Chinese Listed Companies in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, I.; Guardia-Olmos, J.; Berger, R. Abusive Supervision: A Systematic Review and New Research Approaches. Front. Commun. 2022, 6, 640908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.P.; Kennedy, J.; Tata, J.; Yukl, G.; Bond, M.H.; Peng, T.K.; Srinivas, E.S.; Howell, J.P.; Prieto, L.; Koopman, P.; et al. The impact of societal cultural values and individual social beliefs on the perceived effectiveness of managerial influence strategies: A meso approach. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2004, 35, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.; Su, S.; Morris, M.W. When is criticism not constructive? The roles of fairness perceptions and dispositional attributions in employee acceptance of critical supervisory feedback. Hum. Relat. 2001, 54, 1155–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.D.; Tan, B.Z.; Zhou, L.; Huang, H.Q. When Does Abusive Supervision Affect Job Performance Positively? Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedahanov, A.T.; Abdurazzakov, O.S.; Fayzullaev, A.K.; Sun, W. When Does Abusive Supervision Foster Ineffectual and Defensive Silence? Employee Self-Efficacy and Fear as Contingencies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangirala, S.; Ramanujam, R. Exploring Nonlinearity in Employee Voice: The Effects of Personal Control and Organizational Identification. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 1189–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellars, K.L.; Tepper, B.L.; Duff, M.K. Abusive supervision and subordinates’ organizational citizenship behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 1068–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Chen, Z.X.; Sun, L.Y.; Debrah, Y.A. Antecedents and outcomes of abusive supervision: Test of a trickle-down model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, G. Abusive Supervision and Employee Performance: Mechanisms of Traditionality and Trust. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2009, 41, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, A.C.; Schaubroeck, J.M.; Li, Y. Social Exchange Implications of Own and CoWorkers’ Experiences of Supervisory Abuse. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 57, 1385–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Wnag, Q.K. The Effect of Relational Capital on Organizational Performance in Supply Chain: The Mediating Role of Explicit and Tacit Knowledge Sharing. Sustainability 2022, 13, 10635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.Z.; Naqshbandi, M.M.; Bashir, M.; Ishak, N.A. Mitigating knowledge hiding behaviour through organisational social capital: A proposed framework. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B.J. Consequences of Abusive Supervision. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B.J.; Duffy, M.K.; Shaw, J.D. Personality moderators of the relationship between abusive supervision and subordinates’ resistance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 974–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arindam Bhattacharjee1; Anita Sarkar. Abusive supervision: A systematic literature review. Manag. Rev. Q. 2022, 23, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tepper, B.J.; Moss, S.E.; Lockhart, D.E.; Carr, J.C. Abusive supervision, upward maintenance communication, and subordinates’ psychological distress. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.K.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Wu, L.Z. Abusive Supervision, Perceived Psychological Safety and Voice Behavior. Chin. J. Manag. 2012, 9, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq, D.; Jahanzeb, S.; Fatima, T. Abusive supervision, occupational well-being and job performance: The critical role of attention- awareness mindfulness. Aust. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-R.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. Abusive Supervision and Employee’s Creative Performance: A Serial Mediation Model of Relational Conflict and Employee Silence. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.S.; Ambrose, M.L. Abusive supervision and workplace deviance and the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, E.W.; Milliken, F.J. Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 706–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.T.; Ke, J.L.; Shi, J.T.; Zheng, X.S. Survey on Employee Silence and the Impact of Trust on it in China. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2008, 40, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.W.; Xu, A.J. Power imbalance and employee silence: The role of abusive leadership, power distance orientation, and perceived organizational politics. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 68, 513–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorhead, G.; Montanari, J.R. An Empirical Investigation of the Groupthink Phenomenon. Hum. Relat. 1986, 39, 339–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen. Spirals of Silence: The Dynamic Effects of Diversity on Organizational Voice. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 1393–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.J.; Tang, N.Y. The Antecedents and Consequences of Employee Silence: A Literature Review and Future Prospects. Hum. Resour. Dev. China 2019, 36, 84–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjosvold, D.; Sun, H.F. Understanding conflict avoidance: Relationship, motivations, actions, and consequences. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2002, 13, 142–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouten, J.; Tripp, T.M.; Bies, R.; De Cremer, D. When something is not right: The value of silence. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 33, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.A.; Gwinner, K.P.; Meuter, M.L. A comparison of attitude, personality, and knowledge predictors of service-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insu, K.; Cheol, C.M.; MoonKyo, S. The Effect of Perceived Organizational Support on Service-Oriented Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Role of Service Performance as a Mediator. Yonsei Bus. Rev. 2011, 48, 243–267. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, G.X.; Jia, Y.; Mu, W.L.; Wang, T. The Paradoxical Effects of the Contagion of Service-Oriented Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuan, L.T.; Rowley, C.; Masli, E.; Le, V.; Nhi, L.T.P. Nurturing service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior among tourism employees through leader humility. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T.; Ngan, V.T. Leading ethically to shape service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior among tourism salespersons: Dual mediation paths and moderating role of service role identity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.J.; Zhu, H.; Zhong, H.J.; Hu, L.Q. Abusive supervision and customer-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: The roles of hostile attribution bias and work engagement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 53, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Hand Book of the Oryand Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1998, 94, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital and value creation: The role of intrafirm networks. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital and the creation of value in firms. Acad. Manag. Proc. 1997, 11, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafael, R.; Peter, Z. Social Capital, Corporate Culture, and Incentive Intensity. RAND J. Econ. 2002, 33, 243–257. [Google Scholar]

- Ki-Jang, H.; Sung-Keun, W. A Study on the Effects of Hotel Operation Employee’s Social Capital on the Trust and Cynicism, Turnover Intention. Res. Korea Tour. Leis. 2012, 24, 347–369. [Google Scholar]

- Breaux, D.M.; Perrewe, P.L.; Hall, A.T.; Frink, D.D.; Hochwarter, W.A. Time to Try a Little Tenderness? The Detrimental Effects of Accountability When Coupled With Abusive Supervision. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2008, 15, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobman, E.V.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Bordia, P.; Tang, R.L. Abusive Supervision in Advising Relationships: Investigating the Role of Social Support. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 58, 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.L.; Lee, S.; Park, E.; Yun, S. Knowledge sharing, work-family conflict and supervisor support: Investigating a three-way effect. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 2434–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, M.W.; Khan, Q.; Waqas, A. Person related workplace bullying and knowledge hiding behaviors: Relational psychological contract breach as an underlying mechanism. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, S.L.; Yun, S. A moderated mediation model of the relationship between abusive supervision and knowledge sharing. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, E.; Xu, H.; Lam, C.K.; Miao, Q. Abusive supervision and work behaviors: The mediating role of LMX. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detert, J.R.; Burris, E.R. Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Chen, Y.Y.; Kong, H.W. Abusive Supervision and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediating Role of Networking Behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Liao, Z.Y. Consequences of abusive supervision: A meta-analytic review. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2015, 32, 959–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteside, D.B.; Barclay, L.J. Echoes of silence: Employee silence as a mediator between overall justice and employee outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. Abusive Supervision Impact on the Interpersonal Deviation Behavior of Front-line Employees in the Service Industry. Shandong Soc. Sci. 2016, 12, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Biron, M. Ngative reciprocity and the association between perceived organizational ethical values and organizational deviance. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 875–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.H.; Chou, T.H.; Kittikowit, S.; Hongsuchon, T.; Lin, Y.C.; Chen, S.C. Extending Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Service-Oriented Organizational Citizen Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 839688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Bratslavsky, E.; Muraven, M.; Tice, D.M. Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1252–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeichel, B.J.; Vohs, K.D.; Baumeister, R.F. Intellectual performance and ego depletion: Role of the self in logical reasoning and other information processing. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraven, M.; Baumeister, R.F. Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychol. Bull. 2000, 126, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWall, C.N.; Baumeister, R.F.; Stillman, T.F.; Gailliot, M.T. Violence restrained: Effects of self-regulation and its depletion on aggression. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trougakos, J.P.; Beal, D.J.; Cheng, B.H.; Hideg, L.; Zweig, D. Too drained to help: A resource depletion perspective on daily interpersonal citizenship behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Barsade, S.G.; Staw, M.B.M. Affect and creativity at work. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 367–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beheshtifar, M.; Borhani, H.; Moghadam, M.N. Destructive Role of Employee Silence in Organizational Success. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 275–282. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J. Influence of workplace—Based negative gossip on innovative performance of knowledge—Based employees: Mediating role of employee silence and moderating role of inclusive leadership style. J. Yunnan Minzu Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 35, 88–98. [Google Scholar]

- Jahanzeb, S.; Fatima, T. How Workplace Ostracism Influences Interpersonal Deviance: The Mediating Role of Defensive Silence and Emotional Exhaustion. J. Bus. Psychol. Vol. 2018, 33, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Hsieh, H.H.; Wang, Y.D. Abusive supervision and employee engagement and satisfaction: The mediating role of employee silence. Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 1845–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.L.; Yang, S. Abusive Supervision and Employee Performance: The Mediating role of Employee Silence. Soc. Sci. Front. 2014, 6, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, P.; Roberts, P.W. Friendships among Competitors in the Sydney Hotel Industry. Am. J. Sociol. 2000, 106, 387–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berraies, S.; Lajili, R.; Chtioui, R. Social capital, employees’ well-being and knowledge sharing: Does enterprise social networks use matter? Case of Tunisian knowledge-intensive firms. J. Intellect. Cap. 2020, 21, 1153–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Zhang, K.; Fu, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L. The effects of leader-member exchange, internal social capital, and thriving on job crafting. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2019, 47, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Agarwal, U.A. Workplace bullying and employee silence: A moderated mediation model of psychological contract violation and workplace friendship. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 226–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.X.; Wang, L.H. Influence Process of Social Capital on Innovative Performance in R&D Teams: Integration of the Team’s Psychological Safety and Learning Behaviors. J. Manag. Sci. China 2015, 18, 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.W. Sustainable influence of ethical leadership on work performance: Empirical study of multinational enterprise in South Korea. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.B.; Kang, S.W.; Choi, S.B. Empowering leadership, risk-taking behavior, and employees’ commitment to organizational change: The mediated moderating role of task complexity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, J.F. Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wen, Z.L.; Liang, D.M.; Li, N.N. Moderation effect analysis based multiple linear regression. J. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 38, 715–720. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, H.W.; Ferris, D.L.; Brown, D.J. Does power distance exacerbate or mitigate the effects of abusive supervision? It depends on the outcome. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Variable | Type | Frequency | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 180 | 37.89% |

| Female | 295 | 62.11% | |

| Age | Age under 25 years | 207 | 43.58% |

| 26–30 Years old | 112 | 23.58% | |

| 31–35 Years old | 72 | 15.16% | |

| 36–40 Years old | 53 | 11.16% | |

| 41–50 Years old | 21 | 4.42% | |

| Age more than 50 years | 10 | 2.11% | |

| Education Background | High school degree or below | 11 | 2.32% |

| College degree | 281 | 59.16% | |

| Bachelor degree | 155 | 32.63% | |

| Master’s degree | 19 | 4.00% | |

| PhD degree or above | 9 | 1.89% | |

| Tenure | Work for 1–5 years | 289 | 60.84% |

| Work for 6–10 years | 91 | 19.16% | |

| Work for 11–15 years | 66 | 13.89% | |

| Work for 16–20 years | 10 | 2.11% | |

| Over 20 years of work | 19 | 4.00% | |

| Position | General staff | 257 | 54.14% |

| Low-level managers | 103 | 21.60% | |

| Middle management | 60 | 12.72% | |

| Top management | 32 | 6.66% | |

| Others | 23 | 4.88% | |

| Type of Job | Service staff | 228 | 47.93% |

| Marketing/Advertising | 94 | 19.82% | |

| Administrative/HR/Accounting | 81 | 17.02% | |

| Technology/R & D | 20 | 4.14% | |

| Others | 52 | 11.09% |

| Mean | SD | AVE | ABS | DS | SOCB | RSC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABS | 2.55 | 0.999 | 0.506 | 0.836 | |||

| DS | 2.68 | 0.992 | 0.565 | 0.463 ** | 0.863 | ||

| SOCB | 4.02 | 0.628 | 0.599 | −0.507 ** | −0.573 ** | 0.898 | |

| SC | 3.91 | 0.712 | 0.616 | −0.149 ** | −0.330 ** | 0.221 ** | 0.888 |

| Path | Unstandardized Estimates | Standardized Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | ABS → DS | 0.523 | 0.517 | 0.056 | 9.295 | *** | |

| H2 | ABS → SOCB | −0.172 | −0.302 | 0.033 | −5.200 | *** | |

| H3 | DS → SOCB | −0.272 | −0.484 | 0.037 | −7.309 | *** | |

| H5 | ABS × SC → DS | −0.418 | −0.219 | 0.058 | −4.144 | *** | |

| H6 | ABS × SC → SOCB | −0.054 | −0.050 | 0.030 | −1.069 | 0.283 | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| H4 | ABS → DS → SOCB | −0.250 | 0.038 | −0.329 | −0.182 | *** | |

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | Type of Influence | Effect Size | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | Effect Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abusive Supervision | SOCB | Total Effect | −0.3191 *** | −0.3680 | −0.2701 | |

| Direct Effect | −0.1936 *** | −0.2432 | −0.1440 | 60.67% | ||

| Indirect Effect | −0.1255 *** | −0.1597 | −0.0938 | 39.33% |

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | Effect Size of Lnt | SD | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abusive Supervision | DS | −0.2360 *** | 0.0504 | −0.3350 | −0.1370 |

| SOCB | 0.0428 | 0.0327 | −0.0214 | 0.1070 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, J.; Choi, M.-C.; Park, J.-S. Social Capital—Can It Weaken the Influence of Abusive Supervision on Employee Behavior? Sustainability 2023, 15, 2042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032042

Cheng J, Choi M-C, Park J-S. Social Capital—Can It Weaken the Influence of Abusive Supervision on Employee Behavior? Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032042

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Jie, Myeong-Cheol Choi, and Joeng-Su Park. 2023. "Social Capital—Can It Weaken the Influence of Abusive Supervision on Employee Behavior?" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032042

APA StyleCheng, J., Choi, M.-C., & Park, J.-S. (2023). Social Capital—Can It Weaken the Influence of Abusive Supervision on Employee Behavior? Sustainability, 15(3), 2042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032042