Abstract

Increasing desertification has been threatening the sustainable development of human society. Accordingly, the topic of desertification has garnered increasing attention in ecological development and environmental protection. Since the reform and opening-up (1978), China has been actively engaged in desertification control practices and has achieved remarkable results. However, studies have discussed China’s achievements in desertification control mainly from the perspective of natural science and science and technology. Studies conducting an in-depth analysis from the perspective of public management have been inadequate. This study considers collaborative governance in public management as a crucial theoretical tool to analyze collaborative governance in desertification control. Based on desertification control practices in China, an analysis framework was formed for collaborative desertification governance. The analysis framework encompasses the following four dimensions: (1)value, specifying the means to effectively achieve the value goal of collaboration; (2) institutions, identifying the measures to ensure the long-term operation of collaborative governance; (3) structure, identifying the specific relationship and content of collaboration; and (4) mechanisms, defining the practices for collaborative governance. In addition, the case of the Hobq Desert was considered to analyze the framework through the aforementioned four dimensions.

1. Introduction

Desertification has become crucial for national ecological security. Currently, the total area of desertification is 36 million square kilometers worldwide, constituting a quarter of the land area [1], which has been threatening human life and production. China has been battling large-scale desertification for decades and has been most severely affected by sandstorms. The Fifth Bulletin of Status Quo of Desertification and Sandification in China revealed that, by the end of 2014, the area of desertification land in China was 2.6116 million square kilometers. It constituted more than 27% of the total land area [2] and affected the lives of 400 million Chinese people, resulting in economic losses up to 120 billion yuan each year [3]. Accordingly, the key tasks in the current environmental governance include constantly strengthening desertification control and improving the ecological environment of deserts. Since the early days of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the country has been actively engaged in desertification control practices. In the 1950s, the Northeast Military and Political Commission began farmland protection forest networks in the western part of the Northeast Plain, resulting in advancements in desertification control and accumulating valuable experience. The large-scale control practices began after the reform and opening-up (i.e., China’s policy to conduct reform at home and opening-up to the outside world since 1978) and have become normalized and institutionalized with national large-scale environmental projects such as the “Three North Shelter Forest”, returning farmland to forests, and desertification control and prevention. During the past 40 years since the reform and opening-up, “China has achieved miracles in desertification control, turning 33,300 km2 of sandy land into an oasis” [4].

Significant achievements in desertification control have aroused considerable interest in the academic community. Furthermore, different research results have been acquired from different theoretical perspectives, objects, contents, and methods. Public management mainly focuses on the interpretation and discussion from system, policy, industry, and participation perspectives. A review of the existing literature has revealed the following features. First, studies have focused on analyzing the effects of institutional arrangements and changes in desertification control on the results of desertification control. For instance, there is a study which has analyzed the effects of changes in the rural land use system and reforms of the grassland use rights system on desertification control from the historical perspective [5]. Second, someone has analyzed policy issues in desertification control from the perspective of the policy development history. The main research contents include a development history analysis of policies on desertification prevention and control and experience summary [6,7,8]; the implementation mechanism of desertification control and prevention policy [9]; overall policy stability and policy changes [10]; policy costs [11]; and policy performance evaluation [12]. Third, other studies have analyzed the market operation mode and mechanism of the desertification control industry from the industrial perspective. Furthermore, they have effectively coordinated various elements to promote desertification control. The main research contents include the desertification control industry system [13]; theoretical system and practical model [14]; “Internet + desertification control industry” [15]; and industrial effect evaluation [16]. Fourth, another study has analyzed the process of participation in desertification control from the perspective of multi-subject participation. The main research contents include the mode of participation in the desertification control of enterprises [17] and social groups [18].

China’s desertification governance has resulted in the gradual formation of a relatively mature collaborative governance model after a long-term practice and exploration by the government, the public, enterprises, and associations. For instance, the area of successful desertification control by the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, with the most remarkable results, constituted approximately 40% of the country’s total in the past five years. Particularly, the collaborative governance of the Hobq Desert has become a typical example. As stated by Chinese President Xi Jinping, “the Hobq Desert governance provides China’s experience for the international community to manage environmental ecology” [19]. However, based on the perspective of public management, these studies have hinted at knowledge fragmentation, making the overall theoretical understanding and insight difficult. Accordingly, a collaborative theoretical perspective should be adopted for this study on multi-participation and collaborative practice in desertification control, which is the foundation of this study. This study first examined the theoretical basis and core contents of collaborative governance. Thereafter, based on the analysis of the collaborative governance theory and relevant practices, an analysis framework of the “value system structure mechanism” for collaborative governance in desertification control was constructed. The analysis framework was further verified by considering the desertification control practice in Hobq, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

2. Theoretical Tools

2.1. Theoretical Basis of Collaborative Governance

German physicist Hermann Haken systematically explained the idea of synergy in the book Arbitrariness in nature: Synergetics and evolutionary laws of prohibition [20]. The basic idea of collaborative governance was introduced in the “synergetics” that have gradually developed since the 1970s. Haken opined that synergy is the relation and state of the subsystems that make up everything; thus, synergy is a science of orderly and self-organized collective action under the control of universal laws. There always exists a state of collaboration among subsystems regardless of whether it is the world of physics, chemistry, life science, or the world of people’s economic, social, and scientific management. The basic logic of collaboration is as follows: “in an open system, each component is constantly exploring new positions, new motion processes, or new reflection processes, and many parts of the system are involved in this process” [21]. Haken opined that “order parameters” play a dominant role in the collaborative system. Furthermore, one or several “order parameters” are continuously input into the system through positive or negative feedback, thereby making the whole system reach a new state and a higher order. In a word, synergetic exclusively focuses on the interaction between system elements and subsystems and has become a cross-sectional discipline examining the structure of nature and human society.

During its development, society and the scientific community have increasingly emphasized synergetics. From the perspective of system theory, society is a complex system encompassing multiple subsystems. Accordingly, analyzing ways to effectively synergize the components to maximize the effect is the key goal of the operation of the social system. After entering the post-industrial and globalization era at the end of the last century, human society has witnessed increasingly complex elements of the social system, turbulent situations, abnormal environments, and acute problems. This requires the application of a synergistic approach to every public management practice. At the end of the last century, the theoretical development of public management entered a new paradigm of public governance. The fundamental theoretical cognition of public governance is manifested in three aspects: first, it eliminates the boundaries between traditional government and society as well as government and market and enables multiple subjects to participate in public affairs governance. Second, governance can form a stable structure and conform to a certain logic of social rational action. Third, the governance structure is not a model exclusive to a certain place, culture, or region [22]. The development of the theory of public governance is clearly in line with the need for the management of complex social systems in the post-industrial and globalization era.

To sum up, the prototype of collaborative governance is formed when the two theoretical propositions of synergetics and public governance interrelate. In the process of the governance of problems in the complex social system, the theory of collaborative governance is constantly modified and developed, which has, thus, become a vital part of the governance theory.

2.2. The Core Content of Collaborative Governance

Collaborative governance can be simply interpreted as the superposition of “collaboration” and “governance.” Largely, its understanding and cognition are based on this interpretation. There is a study which has maintained that collaborative governance is the nonlinear collaboration between elements and subsystems in the governance system, effectively integrating chaotic states in the governance structure and realizing a governance model in which the whole is greater than the sum of its parts [23,24]. However, this simple superposition idea cannot comprehensively explain collaborative governance. There is a study which has clarified the concept of collaborative governance from the perspectives of system, platform, and process. For instance, according to the United Nations Commission on Global Governance, “collaborative governance is the sum of the many ways through which individuals and various public or private institutions manage their common affairs. It is a process of unifying different shareholders with conflicting interests and making joint actions. It includes legally binding formal institutions and rules, in addition to informal institutional arrangements that facilitate consultation and reconciliation” [25]. For instance, there is a study which was conducted on the governance of “public pond resources” and proposed an autonomous governance model. The model mainly explains the ways through which some interdependent principals effectively organize themselves to solve free-riding issues and evasion of responsibility and achieve the effective governance of public resources [26]. Professor Kirk of the University of Arizona expanded the research on collaborative governance to a wider range of agents, structures, processes, and actions. Furthermore, the professor proposed a collaborative governance mechanism [27]. Ansell and Gash of the University of California defined collaborative governance as “the participation of one or more public agencies, along with nongovernmental stakeholders, in a formal, consensus-oriented, and deliberate collective decision-making process to achieve the development or implementation of public policies, and rule arrangements of public programs, or public goods.” In addition, they proposed the following six criteria: the collaborative forum is initiated by public agencies or institutions, participants of the collaborative forum include nonstate actors, participants directly engage in decision-making rather than playing an “advisory” role, forums are formally organized and meet collectively, the forum aims to make decisions by consensus, and the focus of the collaborative is on public policy or public management [28]. According to Yu Jianxing et. al., collaborative governance refers to “the actions through which the government, out of governance needs, builds institutionalized communication channels and participation platforms by playing a leading role, strengthens support and cultivation for society, and works with society to enhance its roles of autonomous governance, service provision, and collaborative management” [29].

A review of the aforementioned related research can provide a further understanding of the core content of collaborative governance to comprehensively describe collaborative governance. First, the multi-subject relationship in collaborative governance is more diverse. In Chinese expressions, “cooperation” and “teamwork” are similar to “collaboration.” However, the latter simply implies cooperation and coordination between multiple subjects, but collaboration should also imply other multi-subject relationships such as competition, conflict, and gaming. Furthermore, “integrative governance” and “seamless governance” appear in the combination of “governance.” However, the multi-subject relationship is still monotonous and fails to present the dynamic relationship of multiple subjects. Accordingly, collaborative governance expresses the dynamics and diversity of multiple relationships in the governance process. Second, collaborative governance requires a relatively open system. In addition to the bureaucracy, the subjects of collaborative governance include the public, market players, social organizations, news media, and research institutions. The participation of these multiple subjects requires a relatively open field as well as participation channels and mechanisms; otherwise, collaborative governance is merely an idea on paper. Accordingly, the discontinuity of the traditional closed bureaucratic and policy systems and the provision of collaborative governance is the foundation of an open system. Third, collaborative governance is a collaborative structural system constituting multiple dimensions, which involves collaboration in value creation and consensus building. Collaboration is necessary owing to conflicting values in the governance process, making it difficult to reach a consensus. Thus, creating public values that conform to the actual situation and enable multiple subjects to form a consensus is crucial for collaboration. (1) Collaboration of public policy processes. Collaboration runs through every link of public policies: issue formation, agenda setting, decision-making, fund allocation, policy implementation, and policy evaluation. (2) Collaboration of institutions. Institutional guarantees can be built for collaborative operation by formulating and setting a series of formal or informal institutional rules that all subjects can recognize and abide by. (3) Collaboration of organizations. This refers to breaking the isolated state between departments and achieving effective connection and collaboration between organizations. Finally, collaborative governance requires a series of operating mechanisms as support, which mainly includes the dynamic mechanism to find synergy, participation mechanism for expanding participation, value creation mechanism for managing conflicts, sharing mechanism for sharing information and interaction, and performance evaluation mechanism for measuring the collaboration results.

The aforementioned analysis of the theoretical basis and main contents of collaborative governance provides a more profound understanding of collaborative governance. Currently, Chinese society is facing unprecedented and profound changes. The solution to numerous social problems calls for the role of multiple subjects and their joint efforts, with the ecological environment issue being a major concern. Collaborative governance is essential, given that the ecological environment is a type of public good with nonexclusive characteristics and that it involves multiple subjects, regions, and multiple levels of government in the governance process. Studies on collaborative governance have mostly focused on the construction of analytical frameworks in the field of the ecological environment: the prevention and control of air pollution [30], water environment management [31], cross-domain ecological problems [32], marine ecology [33], ecological compensation [34], ecological restoration [35], and other aspects. Desertification control is a key component of ecological environment governance, for which the theory of collaborative governance provides a theoretical insight.

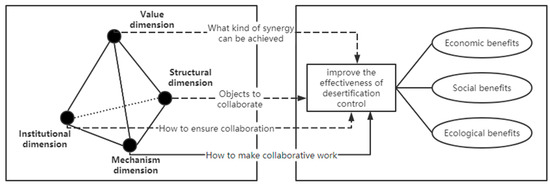

3. Analysis Framework

The formation and evolution of desertification are closely related to the natural environment and human activities. Given that the natural environment has objective regularity, intervention in nature is difficult. Hence, desertification control mainly focuses on the intervention of human activities under the condition of following the laws of nature. In the human activity system, desertification control mainly relates to animal husbandry, mining, logging, farming, water extraction, wasteland reclamation, tourism development, transportation, and urban life. These aspects have become indispensable components for desertification control. This indicates that desertification prevention and control is a complex and systematic project involving different subjects, policies, and resources. It is, thus, clear that collaborative governance in desertification control follows the three basic elements summarized in the previous section at the practical level, that is, it is a system consisting of multiple subjects, open systems, and related mechanisms. On this basis, the logic of collaborative governance in desertification control is further rationalized, namely, how to construct an effective value consensus in an open system, how to guarantee the collaborative action of multiple subjects through institutional supply, how to include more participating subjects in an open system, and how to make the collaboration operate more effectively in an open system. In this regard, interpretations were made from the four dimensions, namely, value, system, structure, and mechanism.

3.1. Value Dimension: Ways to Achieve Collaboration

Values reflect people’s judgments and preferences, and public values reflect people’s collective preferences or ideal consensus or expectations. In the collaborative governance of desertification control, public value is crucial for vision planning, strategic guidance, management, and rectification. As the most popular topic in public management research, the academic community divides public values into two categories: consensus-oriented, mainly reflected in the sense of values, and result-oriented, reflected in the actual results [36]. These two types provide ideas for the analysis of collaborative governance goals in desertification control.

First, ecological security and ecological restoration-oriented value consensus should be built. Two clearly conflicting values exist in desertification control: first, to unilaterally develop animal husbandry, logging, and mining while overlooking the deterioration of desertification, and second, to take active human intervention measures to curb the expansion of desertification. A unified public value consensus on environmental protection and ecological security has been formed at the national level in recent years. However, it will face a series of specific and complex interest demands and value conflicts during its implementation in specific desert areas by specific actors. For instance, the specific desertification control involves local governments, central governments, social organizations, farmers and herdsmen, volunteers, and agricultural companies, and difficulties exist in terms of reaching a consensus on values. Accordingly, the foundation for subsequent collaboration can be laid only by allowing all subjects to reach a value consensus on actively preventing and controlling desertification before taking action. Second, the ecological public value should be created with the production of high-level desertification governance performance as the core. This result-oriented ecological public value should meet the needs of the people. This includes, for instance, the balance between the sustainable use of grassland and grazing prohibition protection, realization of reasonable ecological compensation while protecting grassland and woodland, and realization of significant economic, social, and ecological benefits for a large number of ecological projects. In short, in collaborative governance in desertification control, for consensus-oriented and result-oriented public values, the process should be open and iterative so that the demands, interests, and propositions of collaborative subjects can be effectively reflected.

3.2. Institutional Dimension: Ways to Ensure Sustainable Collaboration

An institution should effectively control uncertainty and regulate certainty [37]. As a process of collective action, collaborative governance often faces uncertainties. However, collaboration implies different ways to achieve control over uncertainties and regulate certainties. Accordingly, collaborative governance is the process of developing institutional rules agreed upon by various subjects. Sustained and long-term collaboration can be achieved only with solid institutional rules; otherwise, collaborative governance will be halted at any time with changes in certain factors.

Within the context of collaborative governance in desertification, focus should be equally placed on formal and informal institutions so that they complement each other and work in synergy. The formal institution stems from a series of mandatory rules and measures that bind organizations and individuals created in the state’s political and administrative structure to achieve specific objectives. It includes various laws, regulations, and administrative rules of the state. For instance, laws, regulations, and measures for desertification control have been issued by the central government, in addition to the directives, regulations, decisions, and plans formulated by local governments and functional departments at all levels. Informal institution derives from practices, norms of conduct, values, cultural traditions, and normative measures embedded in people’s social lives and collective actions. Furthermore, several informal institutions exist for desertification control: water rationing conventions, tree planting and forest protection conventions, and the values of desertification control and prevention passed down across generations.

The neo-institutionalist theory suggests that institutions are derived from people’s rational choices and gradually formed during the long-term interaction among people. For collaborative governance in desertification, people’s rational choices and construction should be strengthened to establish a strong system of institutional support. First, efforts should be made to further improve the supply of formal institutions at all levels of government. This can be achieved by strengthening the institutional connection and integration between regions, sectors, and levels of government and by addressing the fragmentation of formal institutions. Second, institutional resources should be fully explored. Efforts should be made to strengthen the formation and operation of informal institutions in desertification control, as well as to reduce resistance to the implementation of formal institutions and close loopholes. Third, formal and informal institutions should be advanced to complement and support each other. These measures will facilitate institutional advantages in desertification governance, laying a solid foundation for improving collaborative governance in desertification.

3.3. Structural Dimension: Clarify the Contents of Collaboration

The relationship between multiple subjects of governance in desertification control forms the basic structure of collaborative governance. Specific issues concerning collaboration can be clarified only by clearly defining the relationship between multiple subjects. Accordingly, a fundamental content system of collaborative governance can be established.

The content system of collaboration can be clarified based on the actual situation of the ecological governance of desertification and the interrelationship between the governance subjects: (1) The government, market, and society—three main players in the current system of public life—play different roles in desertification control. As the owners of public power, governments are the main policy providers, strategic planners, and public finance (projects) investors in desertification control—an indispensable element of the governance of public resources such as large-scale desertification control. The market plays a vital role in industrial cultivation, financing, industrial cluster, ecological product pricing, and employment expansion in desertification control, compensating for the shortcomings of government and society. People and social organizations can act with self-motivation and organize resources, thereby becoming key players in the governance of desertification in the context of eco-environmental protection and conservation. Accordingly, active collaboration is required to avoid government, market, and social failures in desertification control. (2) With regard to regional collaboration, northern China has been facing widespread desertification, spanning different natural, administrative, economic, and social regions. This implies that desertification control requires organic collaboration in strategies, resources, technologies, and other aspects among different regions and cannot be achieved by a single province or city alone. (3) Regarding cross-functional collaboration, the principle of the division of functions in a bureaucracy leads to the creation of departments. Desertification control involves multiple departments such as agriculture, rural areas, forestry, grassland, natural resources, ecological environment, and development and reform. In reality, some departments are isolated and independent, thereby resulting in the dispersion of resources and conflicts in policies. Therefore, actively promoting collaboration among these departments and boosting their organizational strengths are essential.

3.4. Mechanism Dimension: How to Realize Collaborative Governance

Nobel laureate Leonid Hurwicz et al. identified the significance of mechanism design and asserted that mechanism should be used to explain which distribution or institution can minimize losses [38]. Consequently, the question arises: what is a mechanism? Mechanism refers to the expression of the structure, function, and interrelationship of an organism and the specific operation method that can harmonize relationships among components and play an effective role. As a fixed mechanism for the implementation of system functions, it is a subsystem and comprises three layers: concept, structure, and operation [39]. The concept layer forms the normative guidance for the setting and operation of the entire mechanism, the structure layer forms the basic framework of the mechanism through a series of institutionalized designs, and the operation layer provides the action guide and work basis for the operation of the mechanism through a series of tools. Therefore, a series of mechanisms should be developed in the system of collaborative governance in desertification to facilitate collaborative governance from strategic planning to practice.

Mechanisms for collaborative governance in desertification are mainly manifested in the following aspects. (1) The mechanism of impetus. As mentioned earlier, multiple subjects involved in the collaborative governance of desertification have different impetus for collaboration. We can promote the active participation of all subjects in collaborative practices only by fully harnessing the impetus of all subjects involved in desertification control and bringing them together to generate synergy. (2) The mechanism of sharing. Collaborative governance in desertification requires significant information, technologies, resources, and elements. However, the concentration of these elements in some departments or groups has resulted in the asymmetrical distribution of these elements, thereby leading to unsatisfactory collaborative governance. (3) The mechanism of participation. Collaborative governance in desertification control requires the formation of a multi-entity network system. Participation is crucial in this process, and securing participation is a prerequisite for collaboration. Thus, in a government-led system of governance for desertification, the fixed channels of participation should be expanded to realize the effective participation of the public, enterprises, social organizations, and other subjects. (4) The mechanism of performance evaluation. Whether collaboration improves desertification governance and provides products with satisfactory performance is an indispensable link in collaborative governance. Accordingly, rectifying and managing problems that arise during collaboration and motivating different subjects to further participate is crucial to establish an effective performance evaluation mechanism.

Through the above interpretation from the four dimensions of value, institution, structure, and mechanism, an analysis framework for the collaborative governance of desertification can be built as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Analysis framework of the collaborative governance system for desertification control.

4. Case Analysis

The Hobq Desert, the seventh largest desert in China, is located on the south bank of the “arc” of the Yellow River. Spanning 5–20 km from north to south (width) and approximately 370 km from east to west (length), the desert covers Hanggin Banner, Dalad Banner, and Jungar Banner of Ordos, with a total desert area of approximately 16,756 square kilometers, of which migratory dunes constitute 61%. The desert area has a temperate continental semi-arid climate; however, it is close to the Yellow River Basin with a high groundwater level, offering a rich water source for the eradication of desertification. The desert is mainly dominated by migratory dunes, of which migratory dunes, semi-fixed dunes, and fixed dunes constitute 41%, 19%, and 40%, respectively. Its dune morphology includes the chain of sand dunes, complex transverse dunes, trellis dunes, and grated sandsheet. Due to sparse rainfall, weak vegetation, and frequent occurrence of sand and dust weather in this area, as well as its location as the closest desert to Beijing, its sand and dust can approach the Tianjin–Beijing area within two hours. Human factors have continuously exacerbated the level of desertification in this area. Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the regional population has been constantly increasing. Grasslands and woodlands have been reclaimed under the policy of “grain-based development,” resulting in the continuous desertification of the local sandy surface into migratory dunes.

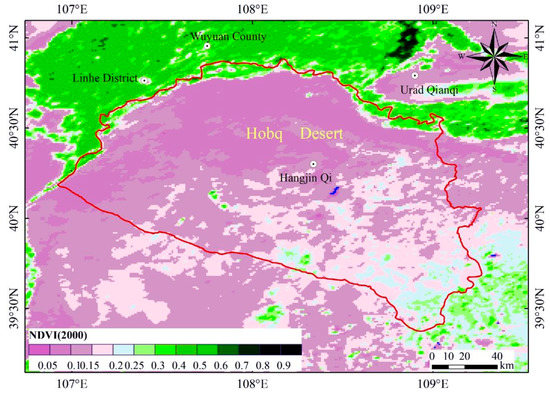

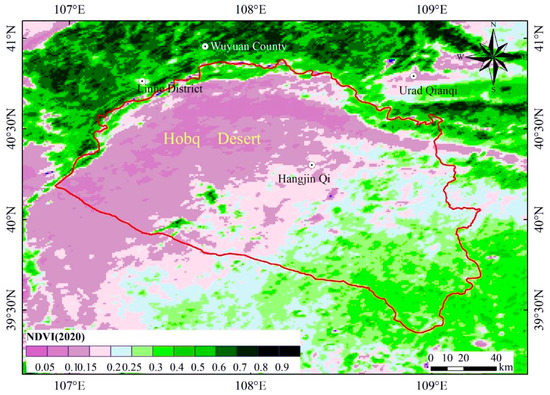

Accordingly, governments at all levels have strengthened the management of and governance in the Hobq Desert since the founding of China, especially after the reform and opening-up. After more than 40 years of development, the total area of desert controlled has reached 6460 square kilometers, 24 billion cubic meters of water resources have been conserved, and an ecological wealth of over 500 billion yuan has been created. This has resulted in the historical transformation from “the desert forcing people to retreat” to “the green development forcing the desert to retreat.” Figure 2 and Figure 3 indicate that the vegetation greening index in theHobq Desert has been increasing continuously for the past two decades. Since 2007, the Hobq International Desert Forum has been held for eight consecutive sessions and has become crucial for the promotion and exchange of governance experience with the world. Furthermore, the international community has focused on this issue, calling Hobq the only desert in the world that has been completely controlled.

Figure 2.

Vegetation index of Hobq Desert in July 2000.

Figure 3.

Vegetation index of Hobq Desert in July 2019.

4.1. Value Dimension of Collaborative Governance in Desertification

The construction of the public value system of collaborative desertification management in Hobq is mainly manifested in four aspects. First, the local people have maintained a basic consensus on cooperative desertification management since the 1980s. Since the reform and opening-up, the policy of “grain-based development” has been gradually abandoned, the previous commune system has gradually disintegrated, and a large number of private companies have emerged. Thus, people have realized that transforming the desert requires cooperation among families, collectives, and enterprises, thereby forming the basic concept of long-term green development. Second, international friends and activists have helped local farmers and herdsmen to establish stronger collaborative values during the long-term desertification control process. Among them, the most famous one is Tooyama Seiei, the Japanese desertification control expert who has long been rooted in Engebei since 1984. Tooyama Seiei led Japanese volunteers to plant trees and control the desert every year. Moved by this behavior to control desertification beyond national borders, local people changed from being suspicious bystanders to supporters and volunteers with a clearer understanding of beliefs and values in collaborative desertification control. Third, various enterprises have realized the economic, social, and ecological benefits of developing the sand industry. They have gradually formed and are practicing the value concept of fixed collaboration among local governments, farmers, and herdsmen. For instance, Yili Group has formed a fixed employment cooperation mechanism with local farmers and herdsmen through public welfare investment and sand industry investment. Fourth, local governments have attached significance to the public values of the ecological priority and sustainable development since the reform and opening-up. Under the guidance of this value concept, they have played a positive role in coordinating, constructing, and leading the value conflicts among multiple subjects in practice to ensure a unified ecological understanding. In summary, Hobq has formed an effective collaborative value system in desertification control. On the one hand, it helps realize the ecological values of sustainable development and the coordination between humans and nature. On the other hand, it actively mobilizes different players to form a cooperative and negotiation-oriented public governance value.

4.2. Institutional Dimension of Collaborative Governance in Desertification

Institutional collaboration is the foundation for the effective operation of collaborative governance in the Hobq Desert. It is mainly manifested in the following two aspects. Since the reform and opening-up, a cross-level, cross-departmental, and cross-regional system of institutional collaboration has been formed in governments at all levels from the central government to the autonomous region, Ordos City, banner, county, township, and sumu. This is mainly reflected in grassland management, forest rights reform, comprehensive management of small watersheds, water and soil protection, and ecological migration. For instance, after the issue of the “Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Forest Management Regulations” in 1984, banner and township governments further issued corresponding policies to supplement and refine the regulations. These policies include “Grazing Prohibition and Resting Work Management Measures of Hanggin Banner,” “Grassland Ecological Protection Management Measures of Hanggin Banner,” “Provisional Measures for the Management of Balanced Grassland Zoning and Rotational Grazing of Hanggin Banner,” and “Implementation Plan for the Reform of the Collective Forest Right System of Hanggin Banner.” These measures have promoted the collaboration and implementation of institutions in forest rights confirmation, forest management and protection responsibilities, punishment measures for behaviors destroying forest land, forestry station construction, forest fire prevention, voluntary afforestation, forest land contracting, forest resource development, grassland and grazing balance, ecological compensation, and returning of farmland to forests. Furthermore, the collaboration of informal institutions plays an important supplementary role in the implementation of formal institutions. For instance, the forest management and protection institution and water use institution formed at Engebei was developed through the long-term practice and negotiation among farmers and herdsmen in desert control and prevention and has been integrated into the local regulations and rules, thereby ensuring regulation, supervision, constraint, and resource integration. During the operation of the forest management and protection system, knowledge and technology training are provided to forest managers based on forestry knowledge. Moreover, farmers and herdsmen regularly hold special forest protection and inspection meetings to negotiate and solve the problems encountered. These two institutions complement each other in content and form as well as promote the effective operation of collaborative desertification control in an orderly manner.

4.3. Structural Dimension of Collaborative Governance in Desertification

The structural dimension describes the relationship between the main subjects in the desertification collaborative governance system, through which the main content of collaboration can be clearly seen. (1) Collaboration between the government and the people. Since the implementation of the “Greening the Motherland” campaign in the early days of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, preliminary cooperation between the government and the people has been initiated. However, cooperation during this time was only conducted on a small scale. Since the reform and opening-up, the cooperation between the government and the public has developed through a series of national projects such as the Three-North Shelter Forest Program, National Natural Forest Conservation Program, and Beijing–Tianjin Sand Source Control Project. For instance, under the promotion of government projects, the government offers seedlings, technologies, knowledge, and funds to the people. Furthermore, farmers and herdsmen conduct afforestation in the spring and autumn according to the government’s plan. (2) Collaboration between enterprises and the people. For desertification prevention and control, Hobq has developed a sand industry centered on tourism, traditional Chinese medicinal materials, ecological cash forests, livestock meat and dairy products, sand building materials and facility, and agriculture [40]. Numerous enterprises have participated in this process. In the entire sand industry system, enterprises and the public have formed a cooperative model of “renting land to households, contracting labor to households, and employing labor to households.” Meanwhile, farmers and herdsmen have become shareholders of the company through equity transfer. This cooperation model has greatly motivated farmers and herdsmen, leading to a win–win result for both enterprises and the public. (3) Collaboration between the government and enterprises. Hobq’s government–enterprise collaboration has formed fixed institutions and platforms. For instance, in the construction of the Engebei Ecological Demonstration Zone, the park management committee and the local government actively promote the concept of “building a nest and attracting phoenixes,” optimize the business environment, enhance investment promotion, and provide enterprises with favorable policies in employment, taxation, infrastructure, and market sales. The fixed cooperation has achieved remarkable results. In the spring of 2022, 24 enterprises signed investment agreements with the Dalad Banner government, totaling RMB 52.66 billion. (4) Collaboration among regions. The success of Hobq desertification control cannot be achieved without regional collaboration at different levels. The collaboration for sandstorm prevention and control in Beijing, Tianjin, and Hebei at the macro level is an example of regional collaboration. As Hobq is closest to Beijing, its governance has received great support from the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. In the autonomous region at the meso level, the “Hulunbuir–Baotou–Erdos Collaborative Planning Outline” has been formulated to strengthen collaboration in policies, funds, technologies, services, and industries for the desert governance and ecological restoration of Hobq between the three cities.

4.4. Mechanism Dimension of Collaborative Governance in Desertification

Collaborative governance in desertification in Hobq cannot be achieved without the support of a series of operation mechanisms, which is mainly manifested in the following aspects. First, the mechanism of impetus; in the Hobq desertification control, each subject forms a stable impetus mechanism according to its practical interests and value demands. For instance, the impetus to make social contributions of the first generation of desert control entrepreneurs, represented by Wang Minghai, through transforming the environment and serving their hometown; the volunteering impetus of international desert control volunteers, represented by Tooyama Seiei, through the afforestation efforts in Hobq; and the impetus driven by the scientific research of young agronomists, represented by Liu Xueqin, who are willing to take roots in deserts and transform classroom knowledge into practical results [41]. The success of theHobq desertification control is inseparable from the active impetus of different subjects, which fundamentally stimulates their willingness to participate in long-term desertification control. Second, the mechanism of sharing; Hobq continues to enhance the sharing of information, technology, and knowledge so that each collaborative subject can obtain the desired basic elements. For instance, Hanggin Banner uses the Internet, big data, and other technologies to integrate the tri-resistant planting resource bank, microbial bacterial bank, desert governance knowledge base, expert think tank, and smart ecological technology system accumulated over the past 30 years to form an extensive sharing system [42]. Through this, it provides a fundamental platform for the acquisition, exchange, and sharing of information and knowledge by different subjects. Third, the mechanism of participation; recently, the three banners in the desert areas of Ordos and Hobq have used new technologies to build diversified channels and platforms for public participation, which are reflected in public decision-making, expert opinions, forest patrols and protection, and desert experience consumption related to desert governance. For instance, the “Internet tree planting + desert experience consumption” formed by Hanggin Banner has transformed the participation action from offline to online. Accordingly, people find it convenient to participate in tree planting, conduct online supervision, and realize desert experience. Fourth, the mechanism of performance evaluation; the results of desertification collaborative governance are evaluated through the performance evaluation mechanism, and the deviation is corrected. The “Hanggin Banner Eco-environmental Protection and Conservation Assessment Method” implemented by Hanggin Banner has established a government-led, public assessment, expert review, and process-transparent assessment mechanism. Violations in the collaborative governance of desertification are rectified and guided to the path of effective collaboration. Through these concrete mechanisms, the collaborative governance in desertification in Hobq has found its foundation and priority tasks.

In short, the Hobq Desert was once “a basin of sand hanging over the capital of China” [43,44]. After more than 40 years of development, it has become an example of successful desert governance across the world owing to the establishment of a diversified collaborative governance model. The collaborative governance model of theHobq desertification control has grown more stable and mature through its dimensions of value, institution, structure, and mechanism.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Briefly, the collaboration modes of desertification governance vary across different countries, leading to differences in the system, focus, and content of collaboration. For desertification control practices worldwide, there are basically three models. First, the government-led model represented by the United States, Canada, Germany, and Romania [17,45]. For instance, the U.S. federal government has played an active role in improving the relevant official legal system, providing a strong policy and regulation guarantee for the westward movement and smooth implementation of desertification control strategies [46]. Simultaneously, the U.S. government has set up the Soil Conservation Service to encourage states to implement soil protection measures, and has ultimately achieved relatively satisfactory results. The second model is the technology-led collaborative model represented by Israel, Arabia, and India. For instance, the Steinberg Desert Research Institute in Israel conducted many projects that are not only directly related to desertification but also indirectly related to solar and wind energy development and utilization, sewage treatment and utilization, desert construction, urban dust reduction, geothermal and brackish groundwater water utilization, water conservation and water resource management, biotechnology, facility agriculture, and 20 other professional fields [47]. The third model is the industry-led collaboration model represented by Australia, Egypt, and Iran [48]. For instance, Australia has fully utilized the resources in desert areas, supported the development and utilization of new energy, eco-tourism, and medicinal plants, drove the transformation and application of high-tech achievements, and made the process of desertification prevention and control effective for the development of emerging and characteristic industries, as well as for poverty alleviation among farmers and herdsmen, realizing the integration of three major benefits [49]. Kubuqi’s desertification governance reflects the three aforementioned models; thus, it can be inferred that Kubuqi governance has integrated the advantages of government-, technology-, and industry-led desertification control modes [50].

Breaking through the perspective of natural science for desertification control and based on the basic theoretical content of collaborative governance and the reality of desertification governance, this study constructs an analytical framework of “value–institution–structure–mechanism” with Chinese characteristics for the collaborative governance of desertification. The typical case of successful desertification control in Kubuqi verified that the framework can interpret the current collaborative governance practice of desertification in China to a certain extent. However, the collaborative governance practice in China’s desertification control and Western collaborative governance theories have some differences. Western collaborative governance theories focus more on the equal collaboration of the spontaneous state of multiple subjects. By contrast, China’s desertification control has formed a government-led, collaborative governance system, such as the “party committee–government-policy-oriented collaborative governance model with industrial investment from enterprises, market-oriented participation of farmers and herdsmen, and continuous technological innovation”. We believe that governments at all levels must play a leading role in the governance of natural ecology in a wide area such as the desert. Otherwise, the tragedy of the commons may emerge, aggravating ecological disasters. Furthermore, the scope and intensity of the collaborative participation of the public, market entities, and social organizations should be expanded.

Through this analytical framework, future collaborative governance in desertification can be further expanded from the perspective of research and practice improvement. In terms of research, efforts should be made to actively promote an exchange between the framework and existing collaborative governance theories and public management theories to analyze and rationalize the theoretical basis of collaborative governance. This will lay a theoretical foundation for the improvement of the framework. In addition, to further improve this analytical framework, cases from other desertification control practices should be used; for example, the case study of the Mu Us desert, Horqin desert, and Hexi Corridor desert. Furthermore, the quantitative analysis of the framework should be continuously advanced. Using econometric models, the quantitative relationship and mechanism of action among the dimensions of value, institution, structure, and mechanism as well as the effectiveness of desertification control should be verified by collecting a large amount of quantitative data. In terms of practical application, first, under this framework, the level of collaboration among the government, market entities, people, and social organizations in desertification control should be continuously strengthened. Second, under the guidance of this framework, the obstacles and dilemmas existing in desertification collaborative governance must be examined. Accordingly, the theoretical collaborative relationship should be explored to achieve reform and overcome bottlenecks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Y. and W.H.; methodology, X.Y.; software, X.Y.; validation, X.Y. and W.H.; formal analysis, W.H.; investigation, W.H.; resources, W.H.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Y.; writing—review and editing, W.H.; visualization, W.H.; supervision, W.H.; project administration, W.H.; funding acquisition, W.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant No. 71974087]; Major Projects of National Social Science Foundation of China [Grant No. 22&ZD089]; Key Laboratory of desert and desertification, Chinese Academy of Sciences [Grant No. kldd-2019-009].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data provided in this study are available upon request by email to the corresponding author (hews@lzu.edu.cn).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- On the World Day to Combat Desertification and Drought, the Global Desertification Area Has Reached 36 Million Square Kilometers. Available online: https://www.tianqi.com/news/292793.html (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Liu, Z.; Song, Y.; Huang, S.; Li, H. Study on Desertification Control in China; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2019; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Zheng, W. China’s desertification control miracle. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 36, 9–12. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2020&filename=STJJ202007004&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=aDqr755EHjU6UHimz0npwaM5hjiqtIiuGnQEwDCNII7tnWp9elYVMEZDQd5vdMae (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- China’s Sand Control Miracle Turns 50 Million Mu of Sand into an Oasis in 40 Years. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/257195577_100275259 (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Fan, S. System Analysis and Performance Evaluation of Desertification Control in China; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2011; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Q.; Chen, J. Historical review and new thinking of Desertification control Policy in Inner Mongolia. Green China 2004, 12, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y. History of Desertification Control in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, G.; Zhao, Y.; Shao, G.; Kong, H.; Lu, Q. Strategies to combat desertification for the twenty-first century in China. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2002, 9, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Q. Research on Implementation Mechanism of Desertification Control Policy in Inner Mongolia; Beijing Forestry University: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, G. Review of desertification control research based on policy process. Sci. Manag. Res. 2021, 39, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S.; Zhao, D.; Lan, J.; Xu, J. Comparative Analysis on Transaction Cost of Two Ecology Management Policies in Sandy Desertification Areas of China. J. Desert Res. 2012, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y. Performance evaluation of desertification control policies based on public value. Arid. Land Geogr. 2013, 36, 897–905. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z.; Feng, Q. Sand Industry, a Strategic New Industry in the 21st Century; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Qin, G.; Yan, Z.; Liu, D.; Li, D.; Wen, L.; Wang, F. Theoretical system and practice model of ecological industry in sandy areas. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Hasi, E. Internet Plus Sand Industry: New Exploration on Industrialization of Desert Management. J. Lanzhou Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2019, 47, 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X.; Liu, L.; Qian, G. Ecological efficiency of circular economy of sand industry in Ulanbuh desert—A case of Jinsha corporation. World Agric. 2020, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Tan, D. Non-cooperative Mode, Cost-Sharing Mode, or Cooperative Mode: Which is the Optimal Mode for Desertification Control? Comput. Econ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Chen, Z.; Wu, M.; Hu, C. Long time series of remote sensing to monitor the transformation research of Kubuqi Desert in China. Earth Sci. Inform. 2020, 13, 795–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: http://www.china.com.cn/opinion/theory/2018-09/06/content_62513044.htm (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Hermann, H. Synergetics: The Secrets of Nature; Shanghai Translation Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2013; p. 207. [Google Scholar]

- Haken, H.; Knyazeva, H. Arbitrariness in nature: Synergetics and evolutionary laws of prohibition. J. Gen. Philos. Sci. 2000, 31, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y. History of Public Administration Theory; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2018; p. 159. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. Discussion on collaborative governance theory. Theor. Mon. 2014, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N. Collaborative governance: Direction and path of rural environmental governance. Theor. Guide 2019, 12, 78–84. Available online: http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-LLDK201912013.htm (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Yu, K. Governance and Good Governance; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2000; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Managing our common resource-introduction. Nat. Resour. 1991, 27, 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, E.; Tina, N.; Stephen, B. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chris, A.; Alison, G. Collaborative governance in the theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Ren, Z. Collaborative governance in contemporary Chinese social construction—An analytical framework. Acad. Mon. 2012, 44, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. Towards collaborative grassroots environmental governance: A case study of air pollution control in A County. J. Fujian Norm. Univ. 2021, 230, 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Zou, F. Let social vitality be aroused: Construction of actor network in the Yangtze River Delta water environment collaborative governance. Jiangsu Soc. Sci. 2022, 1, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.; Su, J.; Dong, S. Research on the current situation and coping path of cross-domain eco-environment collaborative governance. Hunan Soc. Sci. 2021, 5, 92–99. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2021&filename=FLSH202105013&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=bkLP1vvvWirHHnNy6uEXE5G7gUQwF01GWZvC7dPDq3QsPdb3a4pdLGr2I4SxlhHD (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Yang, Z.; Niu, J. Study on collaborative governance strategy of arctic marine ecological security. Pac. J. 2021, 29, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, R.; Li, P. How to realize horizontal coordination of ecological compensation across regional watershed?—Qualitative comparative analysis based on 13 watershed ecological compensation cases. Rev. Public Adm. 2021, 14, 170–190. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W. Multi-subject collaborative governance of ecological environment protection and restoration: A case study of Qilian Mountains. Gansu Soc. Sci. 2018, 2, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, G.; Douglas, M. Government Performance Management—Theory and Method of Government Performance Governance Based on Public Value; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2015; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, T.; Lu, B. Reflection and adjustment of generative logic of collaborative governance. Adm. Forum 2016, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Chen, L. Mechanism design theory of optimal allocation of resources and its application: A review of the 2007 nobel prize in economics. Acad. Res. 2008, 3, 76–82. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=XSYJ200803011&DbName=CJFQ2008 (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Wu, H. Research on Chinese Government Information Sharing Mechanism in the Era of Big Data. Doctoral Dissertation, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Zhen, L.; Du, B. The evolution of desertification control and restoration technology in typical ecologically vulnerable regions. J. Resour. Ecol. 2022, 13, 775–785. [Google Scholar]

- Rooted in the Desert to Produce a Different Kind of Flower. Available online: https://www.fx361.com/page/2021/0609/8430437.shtml (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Solid Waste Treatment Can Learn from the “Kubuqi Model”. Available online: http://www.ordos.gov.cn/gk_128120/sthj/hjpj/202012/t20201218_2823770.html (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- China’s Road to Desertification Control. Available online: http://www.forestry.gov.cn/main/6051/20210619/111240520311709.html (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- How Do Challenges Turn into Opportunities? Available online: https://fanyi.youdao.com/index.html#/ (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Jules, S. Urban desertification and a phenomenology of sustainability: The case of El Paso, Texas. Interdiscip. Environ. Rev. 2014, 15, 160–182. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Xu, D.; Wang, Z. Ecological compensation for desertification control: A review. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, A. Not just tolerated—A global leader: Lessons learned from Israel’s experience in the United Nations Convention to combat desertification. Isr. Stud. 2020, 25, 122–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaidi, J.R.; Allawi, M.Y.; Al-Taie, B.S.; Alobaidi, K.H.; Al-Khayri, J.M.; Abdullah, S.; Ahmad-Kamil, E.I. The environmental, economic, and social development impact of desertification in Iraq: A review on desertification control measures and mitigation strategies. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, W. Earth, air, fire and water: Distinguishing human impacts from natural desertification in South Australia. Trans. R. Soc. South Aust. 2015, 139, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- You, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y. “Chinese Mode” of combating desertification. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2020 Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Environmental Engineering and Sustainable Development (CEESD 2019), Xiamen, China, 5–7 December 2019; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 435. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).