Exploring the Motivations, Abilities and Opportunities of Young Entrepreneurs to Engage in Sustainable Tourism Business in the Mountain Area

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of the Scientific Literature

2.1. Sustainable Mountain Tourism

2.2. Sustainable Entrepreneurship

- -

- systems-thinking competence (understand the complexity and uncertainty of sustainability challenges),

- -

- diversity competence (close collaboration with stakeholders),

- -

- foresighted thinking competence (they see the future as open and try to build it based on their vision for society),

- -

- normative competence (achieve sustainable development objectives, improving the natural and/or communal environment),

- -

- interpersonal competence (engage others to work on the sustainability goals of the sustainable business; this includes engaging partners and stakeholders along with potential customers),

- -

- strategic action competence (create a business case for sustainability which focus on increasing the value of a business by addressing environmental and social dimensions).

2.3. Young Entrepreneurs

2.4. Motivation–Ability–Opportunity (MAO) Framework in Sustainable Entrepreneurship

2.4.1. Motivation

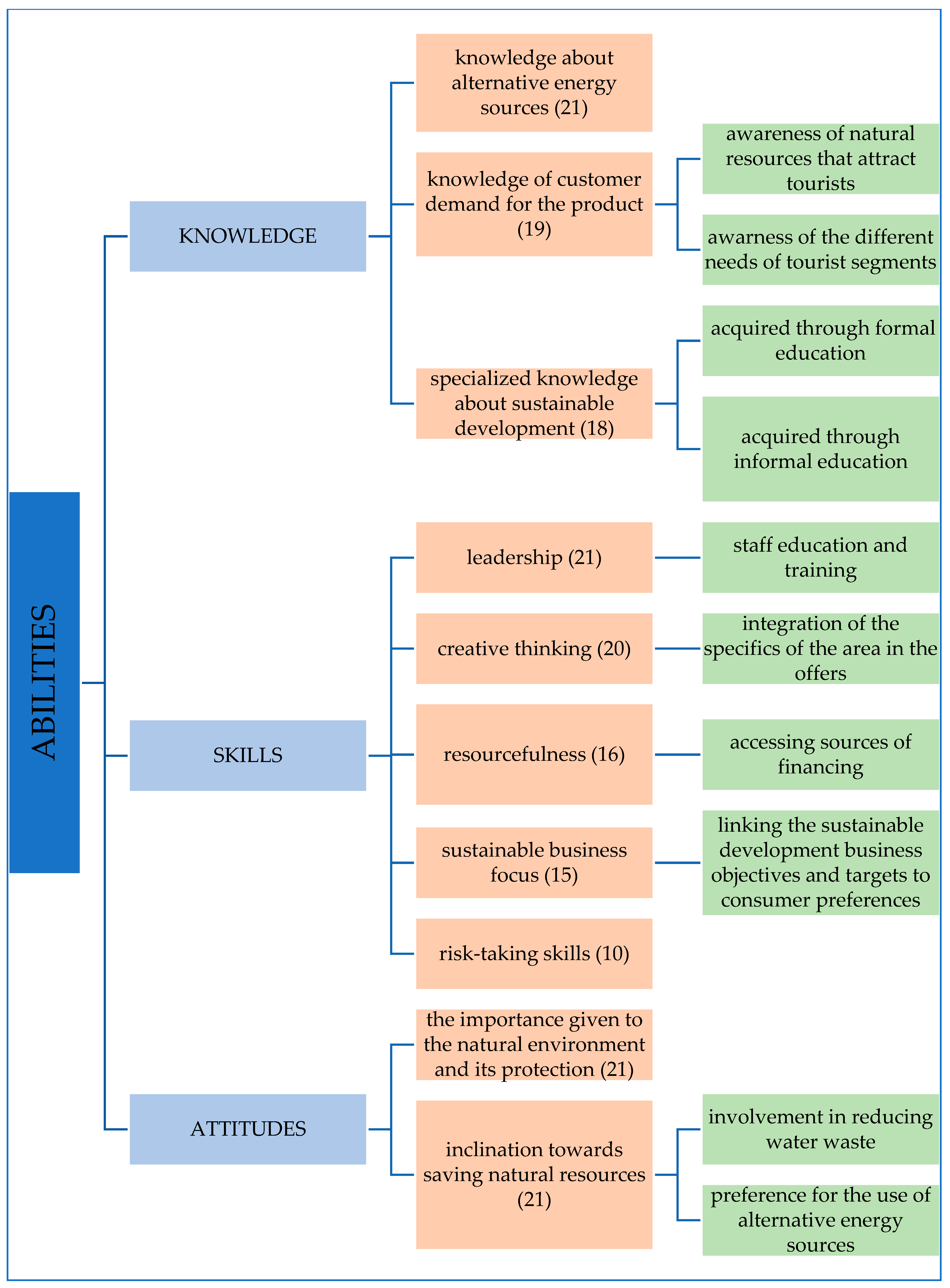

2.4.2. Ability

- -

- Knowledge is the “cognitive” dimension. It covers all the issues and topics that people know or need to know to do their jobs. It is usually associated with “the head”;

- -

- Skills are the “practical” or applied dimension. This dimension refers to what individuals can accomplish or what they need to be able to accomplish their work. It is frequently associated with “hands”.

- -

- Attitudes are the element which applies to the attitudes and values that individuals must adopt to perform their work effectively. It is commonly associated with the “heart”. One of the questions tackled by the present research is: how can entrepreneurs uphold strategic sustainability? The know-what and know-how can be an answer to how their KSA can make the sustainable outcome happen [119]. Sustainable development sustains not only alignment, but also the ambition to learn and share knowledge—knowledge of markets, ways to serve markets, and customer problems [116]. Organizational learning is fundamental to sustaining and developing a competitive advantage in today’s complex, rapidly changing, global economy [120].

2.4.3. Opportunity

3. Brief Characterization of the Local Context

4. Research Methodology

5. Findings

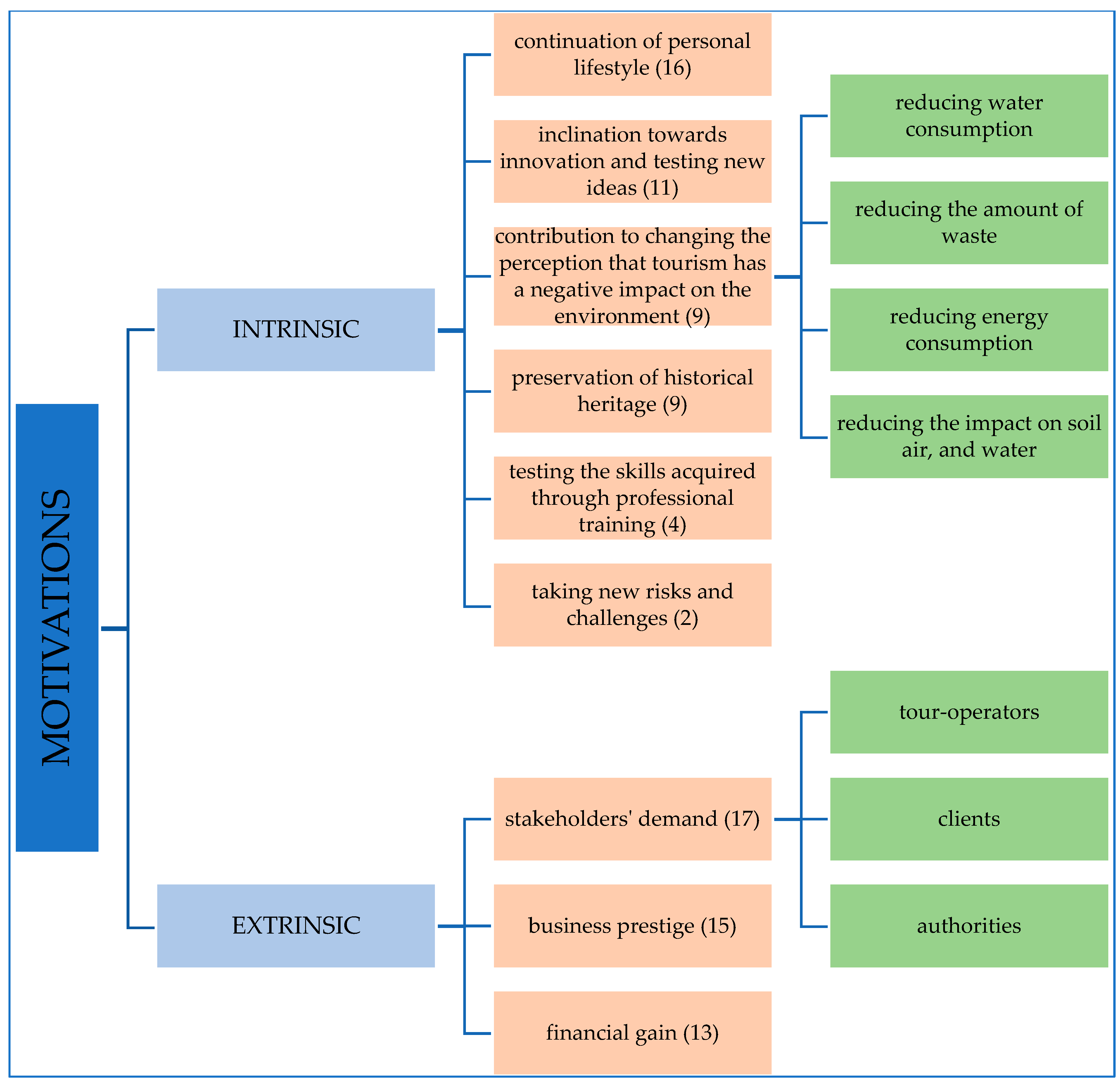

5.1. Motivations Component Findings

“I read that young people are brave in business. Well, I’m a young entrepreneur and I don’t see why I shouldn’t run my business according to the bravest ideas. The sustainable development of a business is still a delicate subject for many old-school entrepreneurs. We, the young people, should show them that business can be done in a different way.”(Y15)

“At check-in, our customers receive information about our policy to reduce water waste. For example, they are asked to contact us when they want us to change their towels, otherwise we will change them daily. We also invite them to support us in our attempts to reduce energy consumption and selectively collect waste. Messages reminding them of our concerns can also be found in the hotel room.”(Y6)

“Yes, I had a course in college about sustainable business development. I liked what I learned, it seemed useful. Ever since I was a student, I decided that one day I would apply what I learned. Now it seems that I can do this in my own business.”(Y20)

“I attended a seminar about the development of sustainable tourism and its impact on sustainability and resilience of the region. The information obtained led me to apply the principles of sustainable development in my business.”(Y13)

- -

- tour operators:”One of the travel agencies we work with asked us to be able to provide proof to clients about our concern for sustainable tourism. We want to be included in the offers of this agency and we did everything necessary to obtain the ecotourism certification” (Y12);

- -

- clients: “our clients ask for high-quality experiences that support the conservation of our special natural places and cultural heritage” (Y9);

- -

- authorities: “There is a Mountain Law, a legal framework that we also benefited from. Natural persons and family associations authorized according to the law, which conduct tourism activities in reception structures such as guesthouses and agritourism farms, benefit from the granting by the local councils of some areas from the available land, under the conditions of the law, to build, develop and exploit guesthouses and agritourism households” (Y6).

5.2. Abilities Component Findings

“In my café, the working environment is pleasant, with music and air conditioning, with a chair for the employee to be able to sit down whenever there are no customers in the café. We also offer work uniforms, sandwiches, and coffee for employees during working hours. The discussions between us are always decent, we don’t get offended, and we don’t raise our voices at each other.”

“In our multi-day trekking tours, we stay in local guesthouses, run by the families in the mountain villages. In that way, the tourists have the chance to taste the home-made food and the local products, to buy handmade souvenirs.”(Y8)

“Our tourists can participate in the current works in the villages (e.g., cutting the grass, milking the cows or sheep). Up in the mountains, we show tourists an authentic sheep farm. There they have a shepherd’s lunch called “bulz” (polenta with cheese). Tourists are interested to find out how the cheese is produced in a traditional way. The tourists could taste a special yogurt called “jintița” (cannot be found in the local markets or big markets).”(Y2)

“We offer tourists the opportunity to enjoy the “peace of nature” of the mountains.”(Y4)

“We brought to the store postcards and objects with images inspired by the landscapes in our area.”(Y19)

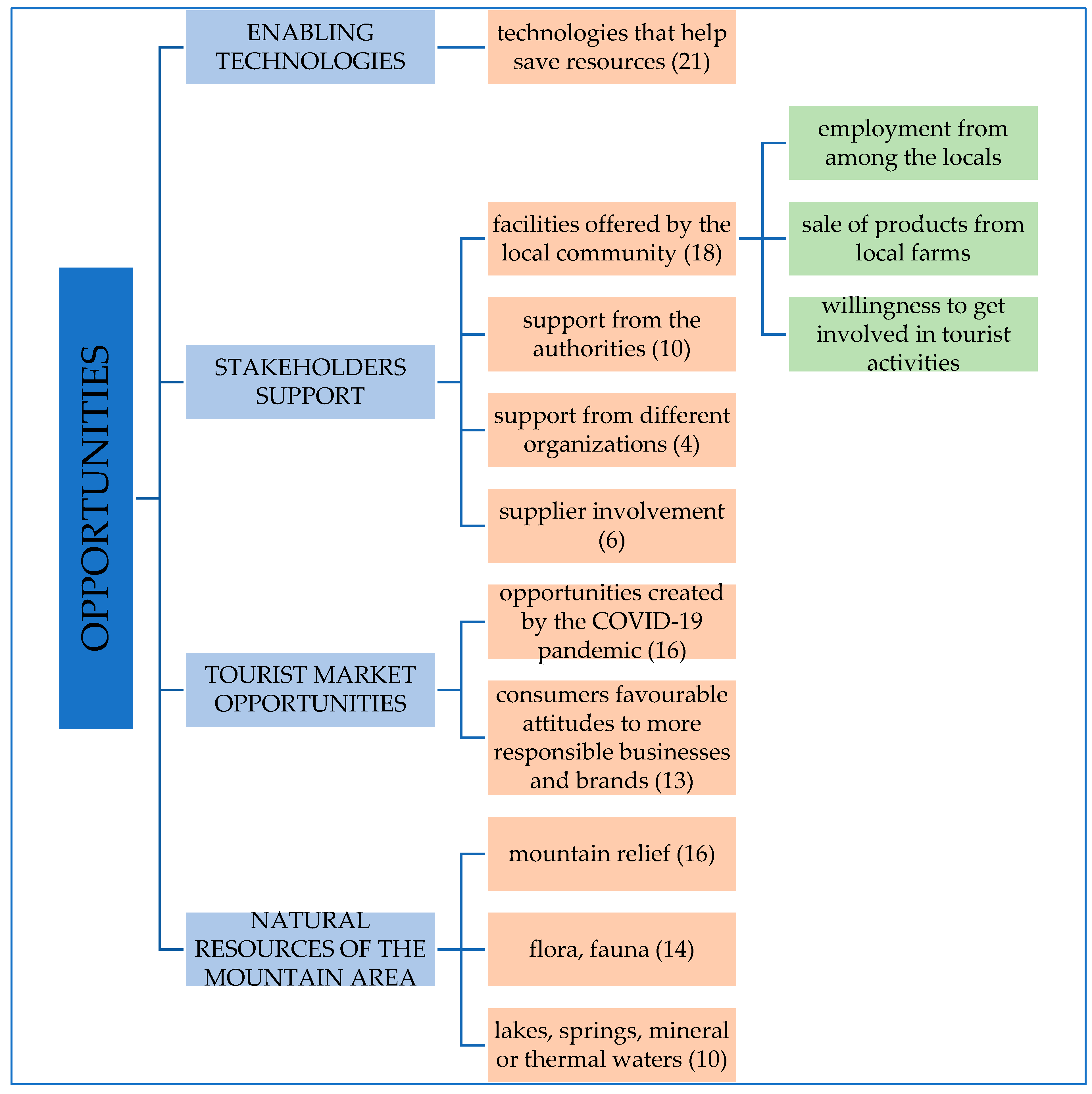

5.3. Opportunities Component Findings

“The restrictions imposed by COVID have brought tourists and nature together. I thought that now is the right time to let them know that we want to be recognized as an environmentally friendly coffee shop.”(Y10)

“There is a rising consumer sentiment around sustainability and local impact. This opens new perspectives for development.”(Y5)

“The development of a sustainable mountain tourism that considers the human—nature communion based on respect and gratitude represents the desired way of valorizing the mountain heritage.”(Y2)

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Policy and Management Implications

7. Conclusions

8. Limitation and Future Research Needs

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gast, J.; Gundolf, K.; Cesinger, B. Doing Business in a Green Way: A Systematic Review of the Ecological Sustainability Entrepreneurship Literature and Future Research Directions. J. Clean Prod. 2017, 147, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euromontana. Being Young in a Mountain Area. Available online: https://www.euromontana.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/2022-01-24-Being-young-in-a-mountain-area_FinalReport_EN.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Euromontana. La Mobilisation du Bois et L’organisation des Filieres en Montagne. Available online: https://www.euromontana.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/2012-06-21_rapport_complet_FR_light1.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- World Tourism Organization and United Nations Development Programme. Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals—Journey to 2030; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2017; ISBN 9789284419401. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnett, C.; Furnham, A. Who Wants to Be an Entrepreneur? A Study of Adolescents Interested in a Young Enterprise Scheme. J. Econ. Psychol. 1991, 12, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Oswald, A. What Makes a Young Entrepreneur? Handbook of Youth and Young Adulthood; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, S.D.; Jack, S.; Anderson, A.R. From Admiration to Abhorrence: The Contentious Appeal of Entrepreneurship across Europe. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2013, 25, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantanen, T.; Toikko, T. Social Values, Societal Entrepreneurship Attitudes and Entrepreneurial Intention of Young People in the Finnish Welfare State. Poznań Univ. Econ. Rev. 2013, 13, 7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Nyock Ilouga, S.; Nyock Mouloungni, A.C.; Sahut, J.M. Entrepreneurial Intention and Career Choices: The Role of Volition. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 42, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bărbulescu, O.; Tecău, A.S.; Munteanu, D.; Constantin, C.P. Innovation of Startups, the Key to Unlocking Post-Crisis Sustainable Growth in Romanian Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. Sustainability 2021, 13, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llisterri, J.J.; Kantis, H.; Angelelli, P.; Tejerina, L. Is Youth Entrepreneurship a Necessity or an Opportunity; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bosco Ekka, D.G.; Prince Verma, D.; Harishchander Anandaram, D. A Review Of The Contribution Of Youth To Sustainable Development And The Consequences Of This Contribution. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 3564–3574. [Google Scholar]

- Ceptureanu, S.I.; Ceptureanu, E.G. Challenges and Barriers of European Young Entrepreneurs. Manag. Res. Pract. 2015, 7, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Dzemyda, I.; Raudeliūnienė, J. Sustainable Youth Entrepreneurship in Conditions of Global Economy toward Energy Security. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2014, 1, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, B.A.; Almahdi, H.K.; Shah, N. Perceptions of Young Entrepreneurial Aspirants towards Sustainable Entrepreneurship in Pakistan. Kybernetes 2021, 50, 2134–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, A.; Kan, M.; Dogan, H.G.; Tosun, F.; Ucum, I.; Solmaz, C. Evaluation of Young Farmers Project Support Program in Terms of Agri-Entrepreneurship in Turkey. Pak. J. Agric. Res. 2018, 55, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, L.A.; Albuquerque, C. Entrepreneurship Education and the Development of Young People Life Competencies and Skills. ACRN J. Entrep. Perspect. 2012, 1, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hamburg, I. Improving Young Entrepreneurship Education and Knowledge Management in SMEs by Mentors. World J. Educ. 2014, 4, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldhof, G.J.; Malin, H.; Johnson, S.K.; Porter, T.; Bronk, K.C.; Weiner, M.B.; Agans, J.P.; Mueller, M.K.; Hunt, D.; Colby, A.; et al. Entrepreneurship in Young Adults: Initial Findings from the Young Entrepreneurs Study. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 35, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masouras, A. Young Entrepreneurship in Cyprus. Zesz. Nauk. Małopolskiej Wyższej Szkoły Ekon. W Tarn. 2019, 42, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ratten, V. Encouraging Collaborative Entrepreneurship in Developing Countries: The Current Challenges and a Research Agenda. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2014, 6, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israr, M.; Saleem, M. Entrepreneurial Intentions among University Students in Italy. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2018, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Sánchez, V.; Atienza-Sahuquillo, C. Entrepreneurial Intention among Engineering Students: The Role of Entrepreneurship Education. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2018, 24, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, A.; Ahmed, F. Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intentions of Business Students in Pakistan. J. Manag. Sci. 2018, 5, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narzullayeva, G.S.; Mukhtarov, M.M. Impact of Covid-19 on Tourism: The Restoration of Tourism and the Role of Young Entrepreneurs in It. World Econ. Financ. Bull. 2021, 2, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Laesser, C.; St. Beritelli, P. Gallen Consensus on Destination Management. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibra, M. Rogers Theory on Diffusion of Innovation-The Most Appropriate Theoretical Model in the Study of Factors Influencing the Integration of Sustainability in Tourism Businesses. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arco, M.; lo Presti, L.; Marino, V.; Maggiore, G. Is Sustainable Tourism a Goal That Came True? The Italian Experience of the Cilento and Vallo Di Diano National Park. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörisch, J. Entrepreneurship as Facilitator for Sustainable Development? Adm. Sci. Editor. Spec. Issue Adv. Sustain. Entrep. 2016, 6, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Kardos, M. The Relationship between Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Sustainable Development. Research on European Union Countries. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2012, 3, 1030–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qudah, A.A.; Al-Okaily, M.; Alqudah, H. The Relationship between Social Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Development from Economic Growth Perspective: 15 ‘RCEP’ Countries. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2022, 12, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.K.; Daneke, G.A.; Lenox, M.J. Sustainable Development and Entrepreneurship: Past Contributions and Future Directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechavarria, D.M.; Reynolds, P.D. Cultural Norms & Business Start-Ups: The Impact of National Values on Opportunity and Necessity Entrepreneurs. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2009, 5, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, R.; Russo, L.; Parisi, F.; Notarianni, M.; Manuelli, S.; Carvao, S. Mountain Tourism—Towards a More Sustainable Path; FAO: Rome, Italy; The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Rome, Italy, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-135416-2. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization. Sustainable Mountain Tourism—Opportunities for Local Communities; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Rome, Italy, 2018; ISBN 9789284420261. [Google Scholar]

- UN United Nations Conference on Environment & Development. 1992. Available online: http://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/agenda21.htm (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- UN United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, Rio+20: Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/rio20/ (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Org, S.U. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development United Nations United Nations Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/ohrlls/sites/www.un.org.ohrlls/files/2030_agenda_for_sustainable_development_web.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Font, X.; McCabe, S. Sustainability and Marketing in Tourism: Its Contexts, Paradoxes, Approaches, Challenges and Potential. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epuran, G.; Dovleac, L.; Ivasciuc, I.S.; Tescașiu, B. Sustenability and Organic Growth Marketing: An Exploratory Approach on Valorisation of Durable Development Principles in Tourism. Amfiteatru. Econ. J. 2015, 17, 927–937. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. UNWTO Making Tourism More Sustainable A Guide for Policy Makers Employment Quality Community Wellbeing Biological Diversity Economic Viability Local Control Physical Integrity Environmental Purity Local Prosperity Visitor Fulfillment Cultural Richness Resource Efficiency Social Equity. 2015. Available online: www.unep.frwww.world-tourism.org (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Wade, B. Why Companies Need to Embrace Sustainability as a Strategic Imperative Rather than an Operational Choice. Available online: https://www.entrepreneur.com/en-au/growth-strategies/why-companies-need-to-embrace-sustainability-as-a-strategic/331743 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Tilley, F.; Young, W. Sustainability Entrepreneurs: Could They Be the True Wealth Generators of the Future? Green Manag. Int. 2009, 55, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hockerts, K.; Wüstenhagen, R. Greening Goliaths versus Emerging Davids—Theorizing about the Role of Incumbents and New Entrants in Sustainable Entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, B.D. Sustainability-Driven Entrepreneurship: Principles of Organization Design. J. Bus. Ventur 2010, 25, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, I.; Ucbasaran, D. Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Career Transitions: The Role of Individual Identity. In Proceedings of the 8th International AGSE Entrepreneurship Research Exchange Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 30 November–2 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Koe, W.-L.; Omar, R.; Majid, I.A. Factors Associated with Propensity for Sustainable Entrepreneurship. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 130, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, T.J.; McMullen, J.S. Toward a Theory of Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Reducing Environmental Degradation through Entrepreneurial Action. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koe, W.L.; Majid, I.A. Socio-Cultural Factors and Intention towards Sustainable Entrepreneurship. Eurasian J. Bus. Econ. 2014, 7, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, B.; Winn, M.I. Market Imperfections, Opportunity and Sustainable Entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, J.G.; Venkataraman, S. The Entrepreneur–Environment Nexus: Uncertainty, Innovation, and Allocation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Gedajlovic, E.; Neubaum, D.O.; Shulman, J.M. A Typology of Social Entrepreneurs: Motives, Search Processes and Ethical Challenges. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidinger, C. Sustainable Entrepreneurship Business Success through Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, P.; Bosma, N.; Autio, E.; Hunt, S.; de Bono, N.; Servais, I.; Lopez-Garcia, P.; Chin, N. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: Data Collection Design and Implementation 1998?2003. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 205–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, J.; Walton, S. What Motivates Ecopreneurs to Start Businesses? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2010, 16, 204–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlange, L.E. Stakeholder Identification in Sustainability Entrepreneurship. Greener Manag. Int. 2006, 2006, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzelt, H.; Shepherd, D.A. Recognizing Opportunities for Sustainable Development. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brink, J. The Entrepreneur’s Sustain-Ability. Education 2017, 8, 416–430. [Google Scholar]

- Power, S.; di Domenico, M.; Miller, G. The Nature of Ethical Entrepreneurship in Tourism. Ann. Tour Res. 2017, 65, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashley, C.; Rowson, B. Lifestyle Businesses: Insights into Blackpool’s Hotel Sector. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H. Small Business Champions for Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsing, M.; Perrini, F. CSR in SMEs: Do SMEs Matter for the CSR Agenda? Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2009, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassin, Y.; van Rossem, A.; Buelens, M. Small-Business Owner-Managers’ Perceptions of Business Ethics and CSR-Related Concepts. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 425–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condon, L. Sustainability and Small to Medium Sized Enterprises—How to Engage Them. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2004, 20, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorio, A. Young Adults and Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Role of Culture and Demographic Factors. J. Int. Bus. Entrep. Dev. 2017, 10, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eller, F.J.; Gielnik, M.M.; Wimmer, H.; Thölke, C.; Holzapfel, S.; Tegtmeier, S.; Halberstadt, J. Identifying Business Opportunities for Sustainable Development: Longitudinal and Experimental Evidence Contributing to the Field of Sustainable Entrepreneurship. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1387–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor GEM Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/reports/latest-global-report (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Bosma, N.; Levie, J. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: 2009 Global Report; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bosma, N.; Schott, T.; Terjesen, S.; Kew, P. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2015 to 2016: Special Topic Report on Social Entrepreneurship. 2016. Available online: file:///C:/Users/Simona%20Ivasciuc/Downloads/BosmaSchottTerjesenKew2016GEMSocialEntrepreneurshipspecialreport.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- ILO Youth Employment (Youth Employment). Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/youth-employment/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Langevang, T.; Gough, K.V. Diverging Pathways: Young Female Employment and Entrepreneurship in Sub-Saharan Africa. Geogr. J. 2012, 178, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeka, B.H.; Rimmington, M. Entrepreneurship as a Career Option for African Youths. J. Dev. Entrep. 2011, 16, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buang, N.A. Entrepreneurship Career Paths of Graduate Entrepreneurs in Malaysia. Res. J. Appl. Sci. 2011, 6, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielnik, M.M.; Zacher, H.; Wang, M. Age in the Entrepreneurial Process: The Role of Future Time Perspective and Prior Entrepreneurial Experience. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 1067–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athayde, R. Measuring Enterprise Potential in Young People. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P.B.; Stimpson, D.V.; Huefner, J.C.; Hunt, H.K. An Attitude Approach to the Prediction of Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1991, 15, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krosnick, J.A.; Boninger, D.S.; Chuang, Y.C.; Berent, M.K.; Carnot, C.G. Attitude Strength: One Construct or Many Related Constructs? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 65, 1132–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos-Nehles, A.C.; van Riemsdijk, M.J.; Kees Looise, J. Employee Perceptions of Line Management Performance: Applying the AMO Theory to Explain the Effectiveness of Line Managers’ HRM Implementation. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 52, 861–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, A.O.; Arasanmi, C.N.; Raman, M.; Tan, C.N.-L. Ability, Motivation, Opportunity and Sociodemographic Determinants of Internet Usage in Malaysia. Inf. Dev. 2019, 35, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, D.A.; Spangler, W.D. Putting Together the Pieces: A Closer Look at the Determinants of Job Performance. Hum. Perform. 1989, 2, 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacInnis, D.J.; Moorman, C.; Jaworski, B.J. Enhancing Consumers’ Motivation, Ability, and Opportunity to Process Brand Information from Ads: Conceptual Framework and Managerial Implications. J. Mark. 1991, 55, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ölander, F.; ThØgersen, J. Understanding of Consumer Behaviour as a Prerequisite for Environmental Protection. J. Consum. Policy 1995, 18, 345–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, P.; Purcell, J. Strategy and Human Resource Management; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, J. The Ability-Motivation-Opportunity Framework for Behavior Research in IS. In Proceedings of the 2007 40th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS’07), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–6 January 2007; p. 250a. [Google Scholar]

- Bigné, E.; Ruiz, C.; Andreu, L.; Hernandez, B. The Role of Social Motivations, Ability, and Opportunity in Online Know-How Exchanges: Evidence from the Airline Services Industry. Serv. Bus. 2015, 9, 209–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benet-Zepf, A.; Marin-Garcia, J.A.; Küster, I. Clustering the Mediators between the Sales Control Systems and the Sales Performance Using the AMO Model: A Narrative Systematic Literature Review. Intang. Cap. 2018, 14, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, T.; Li, B.; Maclaren, V. An Evaluation of a Consumer Food Waste Awareness Campaign Using the Motivation Opportunity Ability Framework. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibian, A.-R.; Ispas, A. An Approach to Applying the Ability-Motivation-Opportunity Theory to Identify the Driving Factors of Green Employee Behavior in the Hotel Industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, J. Motivation, Ability and Opportunity to Participate: A Reconceptualization of the RAND Model of Audience Development. J. Arts Manag. 2004, 7, 22–33. [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild, M.L. Carrots, Sticks, and Promises: A Conceptual Framework for the Management of Public Health and Social Issue Behaviors. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokmans, M. MAO-Model of Audience Development: Some Theoretical Elaborations and Practical Consequences. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Arts and Cultural Managernent, Montreal, QU, Canada, 2005; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, K.; Petrick, J.F. Investigating the Role of Motivation, Opportunity and Ability (MOA) on Travel Intentions: An Application of the MOA Model in Cruise Tourism. Univ. Mass. Amherst. Sch. @UMass Amherst 2016, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Batra, R.; Ray, M.L. Affective Responses Mediating Acceptance of Advertising. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepson, A.; Clarke, A.; Ragsdell, G. Applying the Motivation-Opportunity-Ability (MOA) Model to Reveal Factors That Influence Inclusive Engagement within Local Community Festivals: The Case of UtcaZene 2012. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2013, 4, 186–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emens, S.; White, D.W.; Klein, T.A.; Edwards, Y.D.; Mann, S.R.; Flaschner, A.B. Self-Congruity and the MOA Framework: An Integrated Approach to Understanding Social Cause Community Volunteer Participation. J. Mark. Dev. Compet. 2014, 83, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, E.; Stokmans, M. Drivers and Barriers for the Adoption of Hazard-Resistant Construction Knowledge in Nepal: Applying the Motivation, Ability, Opportunity (MAO) Theory. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefendorff, J.M.; Chandler, M.M. Motivating Employees. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (Vol. 3): Maintaining, Expanding, and Contracting the Organization; Zedeck, S., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality and Behavior; Open University Press: Milton Keynes, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Elbaz, A.M.; Agag, G.M.; Alkathiri, N.A. How Ability, Motivation and Opportunity Influence Travel Agents Performance: The Moderating Role of Absorptive Capacity. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Mittal, B. A Theory of Involvement in Consumer Behavior: Problems and Issues. Res. Consum. Behav. 1985, 1, 201–232. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Xu, X.; Chen, C.; Menassa, C. Understanding Energy-Saving Behaviors in the American Workplace: A Unified Theory of Motivation, Opportunity, and Ability. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 51, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarikwal, L.; Gupta, J. The ImpacT of HIgh Performance Work PracTIces and OrganIsaTIonal CITIzenshIp BehavIour on Turnover InTenTIons. J. Strateg. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 2, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Minbaeva, D.B. Strategic HRM in Building Micro-Foundations of Organizational Knowledge-Based Performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2013, 23, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Matyakubov, U.; Matniyozov, M.; Shaken, A.; Mika, M. Women Entrepreneurs in Tourism in a Time of a Life Event Crisis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, G.; Borgia, D.; Schoenfeld, J. The Motivation to Become an Entrepreneur. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2005, 11, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateljevic, I.; Doorne, S. “Staying Within the Fence”: Lifestyle Entrepreneurship in Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Carlsen, J. Family Business in Tourism: State of the Art. Ann. Tour Res. 2005, 32, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G. Entrepreneurial Cultures and Small Business Enterprises in Tourism. In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Tourism; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 120–131. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, C.; Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J. Entrepreneurs in Rural Tourism: Do Lifestyle Motivations Contribute to Management Practices That Enhance Sustainable Entrepreneurial Ecosystems? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Garay, L.; Jones, S. Sustainability Motivations and Practices in Small Tourism Enterprises in European Protected Areas. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Garay, L.; Jones, S. A Social Cognitive Theory of Sustainability Empathy. Ann. Tour Res. 2016, 58, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, R.G.M. Changing Garbage Disposal Patterns of Consumers: Motivation, Ability, and Performance. J. Public Policy Mark. 1991, 10, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F.L.; Hunter, J.E. The Validity and Utility of Selection Methods in Personnel Psychology: Practical and Theoretical Implications of 85 Years of Research Findings. Psychol Bull. 1998, 124, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhart, B. Horizontal and Vertical Fit in Human Resource Systems. In Perspectives on Organizational Fit; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 317–350. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, H. The Nature of Entrepreneurship. In Dynamic Entrepreneurship in Central and Eastern Europe; Delwel Publishers: Hague, The Netherlands, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Shane, S. Prior Knowledge and the Discovery of Entrepreneurial Opportunities. Organ. Sci. 2000, 11, 448–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, N.; Flood, P.C.; Bosak, J.; Morris, T.; O’Regan, P. Exploring the Performance Effect of HPWS on Professional Service Supply Chain Management. Supply Chain Manag. An. Int. J. 2013, 18, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe Youth Work Competence—Youth Portfolio. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/youth-portfolio/youth-work-competence (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Chai, K.-H.; Baudelaire, C. Understanding the Energy Efficiency Gap in Singapore: A Motivation, Opportunity, and Ability Perspective. J. Clean Prod. 2015, 100, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedstrom, G.; Poltorzycki, S.; Stroh, P. Sustainable Development: The next Generation of Business Opportunity; Prism-Cambridge Massachusetts: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schoonhoven, C.B.; Eisenhardt, K.M.; Lyman, K. Speeding Products to Market: Waiting Time to First Product Introduction in New Firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of Concepts, Research and Practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittell, R.; Magnusson, M.; Merenda, M. The Keys to Successful Sustainability Entrepreneurship. Available online: https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_the-sustainable-business-case-book/s09-02-the-keys-to-successful-sustain.html (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Barbier, E.B. The Concept of Sustainable Development. Environ. Conserv. 1987, 14, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Towards the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable Development. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1994, 36, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A.A.; Kates, R.W.; Parris, T.M. Sustainability Values, Attitudes, and Behaviors: A Review of Multinational and Global Trends. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2006, 31, 413–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristache, N.; Soare, I.; Nastase, M.; Antohi, V.M. Integrated Approach of the Entrepreneurial Behaviour in the Tourist Sector from Disadvantaged Mountain Areas from Romania. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 5514–5530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MADR Anexǎ Memorandum, Orientǎri Strategice Naționale Pentru Dezvoltarea Durabilǎ a Zonei Montane Defavorizate (2014–2020). 2014. Available online: https://www.madr.ro/docs/dezvoltare-rurala/memorandum/Anexa-Memorandum-zona-montana-defavorizata-2014-2020.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Bălălău, L.; Deák Ștefania, E.; Klein, A.; Toader, M.; József, I.; Szász, F.; Dyuvbanova, C.S. Descrierea CIP a Bibliotecii Naţionale a României Romania’s Sustainable Development. 2018. Available online: http://www.ddd.gov.ro/ (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Legea Muntelui nr. 197/2018 LEGEA Muntelui.PDF 2021. Available online: https://e-juridic.manager.ro/articole/legea-muntelui-pdf-2019-26225.html (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Matthews, B.; Ross, L. Research Methods; Pearson Higher, Ed.; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, A.; Argade, P.; Barkemeyer, R.; Salignac, F. Trends and Patterns in Sustainable Entrepreneurship Research: A Bibliometric Review and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Ventur. 2021, 36, 106092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuper, A.; Lingard, L.; Levinson, W. Critically Appraising Qualitative Research. BMJ 2008, 337, a1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant, J. Qualitative Research Part II: Participants, Analysis, and Quality Assurance. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2012, 4, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrawadieh, Z.; Altinay, L.; Cetin, G.; Şimşek, D. The Interface between Hospitality and Tourism Entrepreneurship, Integration and Well-Being: A Study of Refugee Entrepreneurs. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 97, 103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghauri, P.; Gronhaug, K. Research Methods in Business Studies: A Practical Guide, 3rd ed.; Financial Times Prentice Hall: Manchester, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, M. Sample Size and Saturation in PhD Studies Using Qualitative Interviews. Forum. Qual. Soc. Res. 2010, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin, S.L. Sample Size Policy for Qualitative Studies Using In-Depth Interviews. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2012, 41, 1319–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. To Saturate or Not to Saturate? Questioning Data Saturation as a Useful Concept for Thematic Analysis and Sample-Size Rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2021, 13, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, B.; Cardon, P.; Poddar, A.; Fontenot, R. Does Sample Size Matter in Qualitative Research?: A Review of Qualitative Interviews in Is Research. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2013, 54, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Mar Alonso-Almeida, M. Water and Waste Management in the Moroccan Tourism Industry: The Case of Three Women Entrepreneurs. Womens Stud. Int. Forum. 2012, 35, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoasong, M.Z.; Kimbu, A.N. Why Hurry? The Slow Process of High Growth in Women-Owned Businesses in a Resource-Scarce Context. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. Life Paths Into Effective Environmental Action. J. Environ. Educ. 1999, 31, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürol, Y.; Atsan, N. Entrepreneurial Characteristics amongst University Students. Educ. Train. 2006, 48, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurapatskie, B.; Darnall, N. Which Corporate Sustainability Activities Are Associated with Greater Financial Payoffs? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.R.; Shepherd, D.A. Entrepreneurs’ Decisions to Exploit Opportunities. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unwto Tourism Trends. 2022. Available online: https://www.unwto-tourismacademy.ie.edu/2021/08/tourism-trends-2022 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Choi, D.Y.; Gray, E.R. The Venture Development Processes of “Sustainable” Entrepreneurs. Manag. Res. News 2008, 31, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.C.; Malin, S. Green Entrepreneurship: A Method for Managing Natural Resources? Soc. Nat. Resour. 2008, 21, 828–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhongming, Z.; Linong, L.; Xiaona, Y.; Wangqiang, Z.; Wei, L. OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2020; OECD. 2020. ISBN 9789264703148. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/urban-rural-and-regional-development/oecd-tourism-trends-and-policies-2020_6b47b985-en (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Hunter, C. Aspects of the Sustainable Tourism Debate from a Natural Resources Perspective. In Sustainable Tourism; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sgroi, F. Forest Resources and Sustainable Tourism, a Combination for the Resilience of the Landscape and Development of Mountain Areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 736, 139539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Huang (Sam), S.; Song, L. Opportunity and Necessity Entrepreneurship in the Hospitality Sector: Examining the Institutional Environment Influences. Tour. Manag. Perspect 2020, 34, 100665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MAO Framework Component | Question | Operational Objective |

|---|---|---|

| M—Motivation | Why are business owners, especially the ones who are at the beginning of their careers, motivated to engage in sustainable behaviors? | Identifying the main motivations that determine a young tourism entrepreneur to adopt a sustainable business behavior |

| A—Ability | How do the young tourism entrepreneur’s knowledge, skills, and abilities make the sustainable outcome happen? | Identifying the abilities that allow young tourism entrepreneurs to adopt a sustainability friendly behavior |

| O—Opportunity | What are the circumstances that make sustainable business actions possible? | Identifying young tourism entrepreneurs’ perception on the opportunities that allow them to do sustainable business |

| ID | Type of Tourism Business Enterprise They Run | Age | Highest Education Level | Education Related to Sustainable Business Development | Number of Years on the Market | Number of Employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y1 | Hotel | 33 | University degree | yes | 8 | 23 |

| Y2 | Travel agency | 29 | University degree | yes | 2 | 2 |

| Y3 | Souvenir shop | 27 | College degree | no | 5 | 0 |

| Y4 | Guesthouse | 27 | University degree | yes | 2 | 5 |

| Y5 | Restaurant | 34 | University degree | no | 9 | 11 |

| Y6 | Guesthouse | 28 | University degree | no | 3 | 7 |

| Y7 | Hotel | 32 | University degree | no | 6 | 19 |

| Y8 | Travel agency | 30 | University degree | yes | 3 | 3 |

| Y9 | Travel agency | 33 | University degree | yes | 5 | 1 |

| Y10 | Cafe | 22 | College degree | no | 1 | 2 |

| Y11 | Cafe | 34 | University degree | yes | 5 | 2 |

| Y12 | Guesthouse | 32 | University degree | no | 4 | 8 |

| Y13 | Vacation rental | 34 | College degree | no | 2 | 1 |

| Y14 | Travel agency | 23 | University degree | no | 1 | 1 |

| Y15 | Cafe | 27 | University degree | yes | 2 | 3 |

| Y16 | Guesthouse | 28 | University degree | no | 2 | 3 |

| Y17 | Vacation rental | 30 | University degree | no | 5 | 0 |

| Y18 | Vacation rental | 31 | College degree | no | 3 | 0 |

| Y19 | Souvenir shop | 21 | College degree | no | 2 | 0 |

| Y20 | Hotel | 32 | University degree | yes | 6 | 34 |

| Y21 | Souvenir shop | 26 | Vocational training | no | 6 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ivasciuc, I.-S.; Ispas, A. Exploring the Motivations, Abilities and Opportunities of Young Entrepreneurs to Engage in Sustainable Tourism Business in the Mountain Area. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1956. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031956

Ivasciuc I-S, Ispas A. Exploring the Motivations, Abilities and Opportunities of Young Entrepreneurs to Engage in Sustainable Tourism Business in the Mountain Area. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):1956. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031956

Chicago/Turabian StyleIvasciuc, Ioana-Simona, and Ana Ispas. 2023. "Exploring the Motivations, Abilities and Opportunities of Young Entrepreneurs to Engage in Sustainable Tourism Business in the Mountain Area" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 1956. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031956

APA StyleIvasciuc, I.-S., & Ispas, A. (2023). Exploring the Motivations, Abilities and Opportunities of Young Entrepreneurs to Engage in Sustainable Tourism Business in the Mountain Area. Sustainability, 15(3), 1956. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031956