Community Participation in the Importance of Living Heritage Conservation and Its Relationships with the Community-Based Education Model towards Creating a Sustainable Community in Melaka UNESCO World Heritage Site

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Intangible Cultural Heritage

- (1)

- Oral traditions and expressions encompass a wide variety of speech forms, including proverbs, riddles, fables, nursery rhymes, stories, myths, epic songs and poems, charms, prayers, chants, songs, dramatic performances, and more. Through it, information, cultural and social values, and collective memory, are all transmitted. It is also essential for preserving tradition.

- (2)

- The performing arts include chanting, pantomime, vocal and instrumental music, dancing, and theatre. It contains several cultural manifestations that showcase human creativity.

- (3)

- Social practices, rituals, and festivals are commonplace routines that shape community and group life and are essential to all participants. It is crucial because it represents the group or society’s identity and is strongly tied to significant occasions, whether they take place in public or private settings.

- (4)

- Knowledge and practices about nature and the universe comprise the community’s developed knowledge, abilities, behaviors, and representations that interact with the environment. Language, oral traditions, sentimental ties to a place, memories, spirituality, and worldview are examples of how this method of understanding the universe is expressed. It also has a significant impact on attitudes and beliefs, as well as numerous social traditions and cultural activities.

- (5)

- Traditional craftsmanship is expressed most succinctly in intangible cultural heritage. It emphasizes the skills and knowledge needed for carpentry rather than the craft of the end product. It must therefore inspire artisans to continue producing their work and passing on their skills to others, particularly those within their communities.

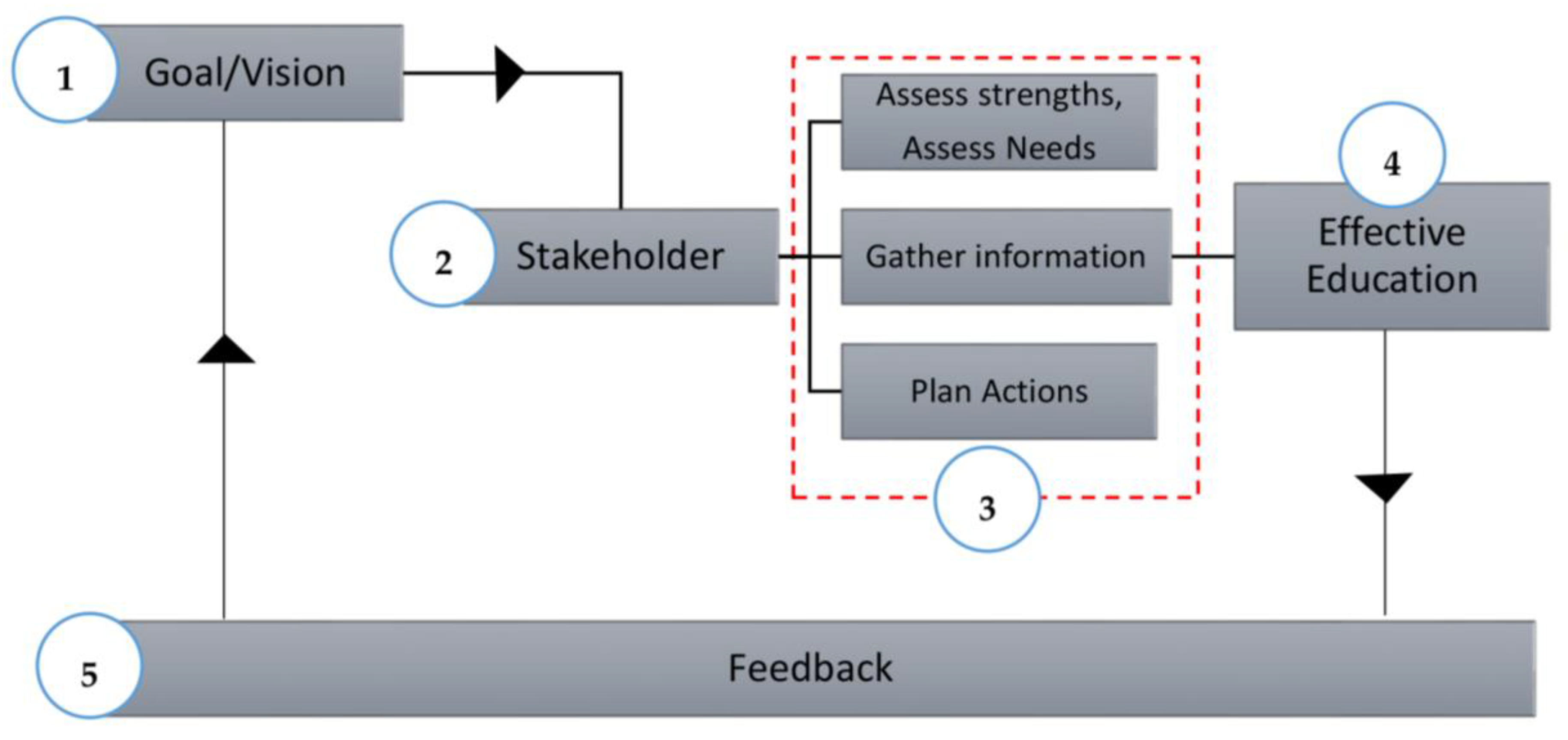

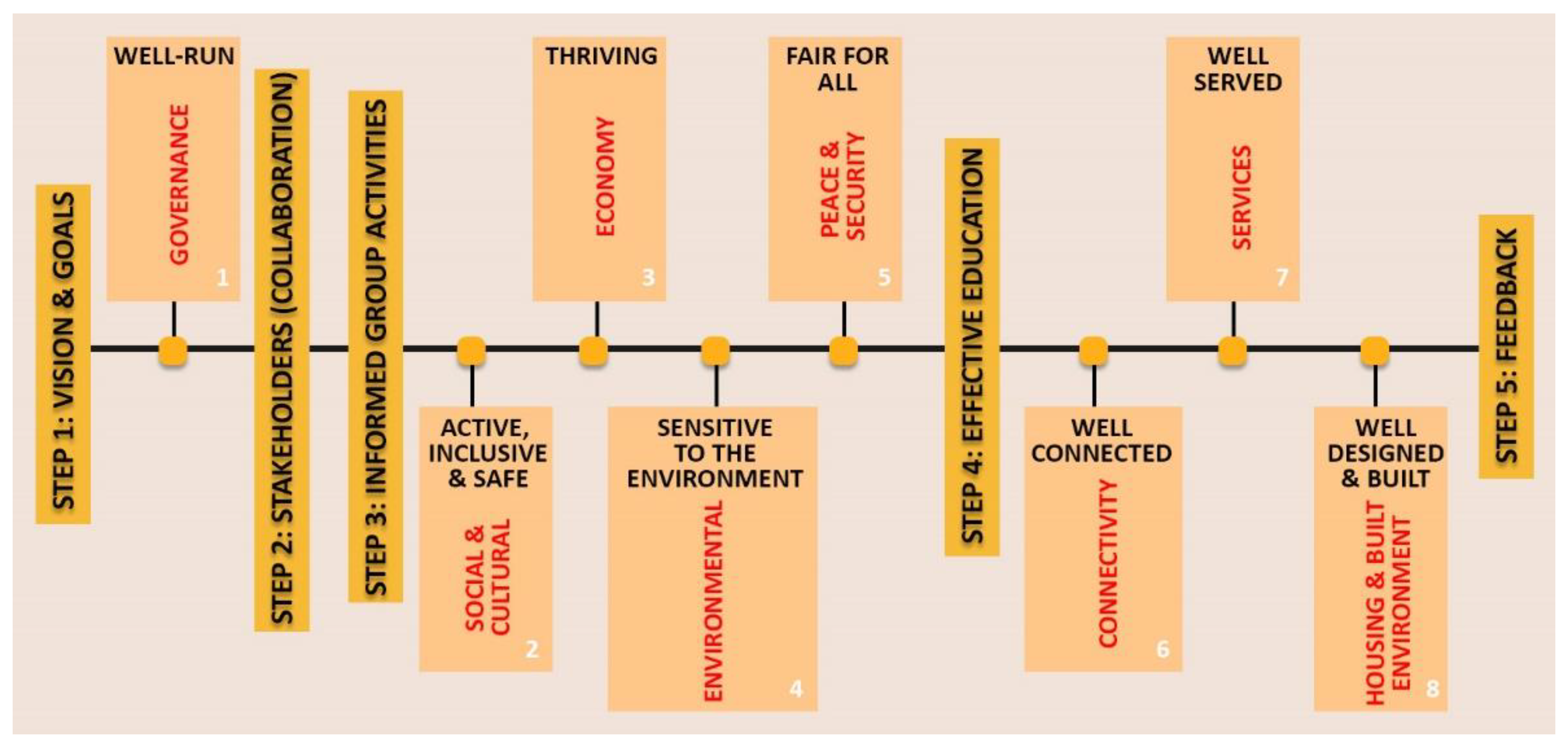

2.2. Community-Based Education (CBE) Model

Informed Group Activities

- Assess the Community’s Strengths and Needs

- ii.

- Gather Information on Community’s Attitude, Cultural Knowledge, and Awareness toward Living Heritage Conservation

- iii.

- Plan Action based on Community Perceptive

2.3. CBE for LH toward Sustainable Community

3. Materials and Methods

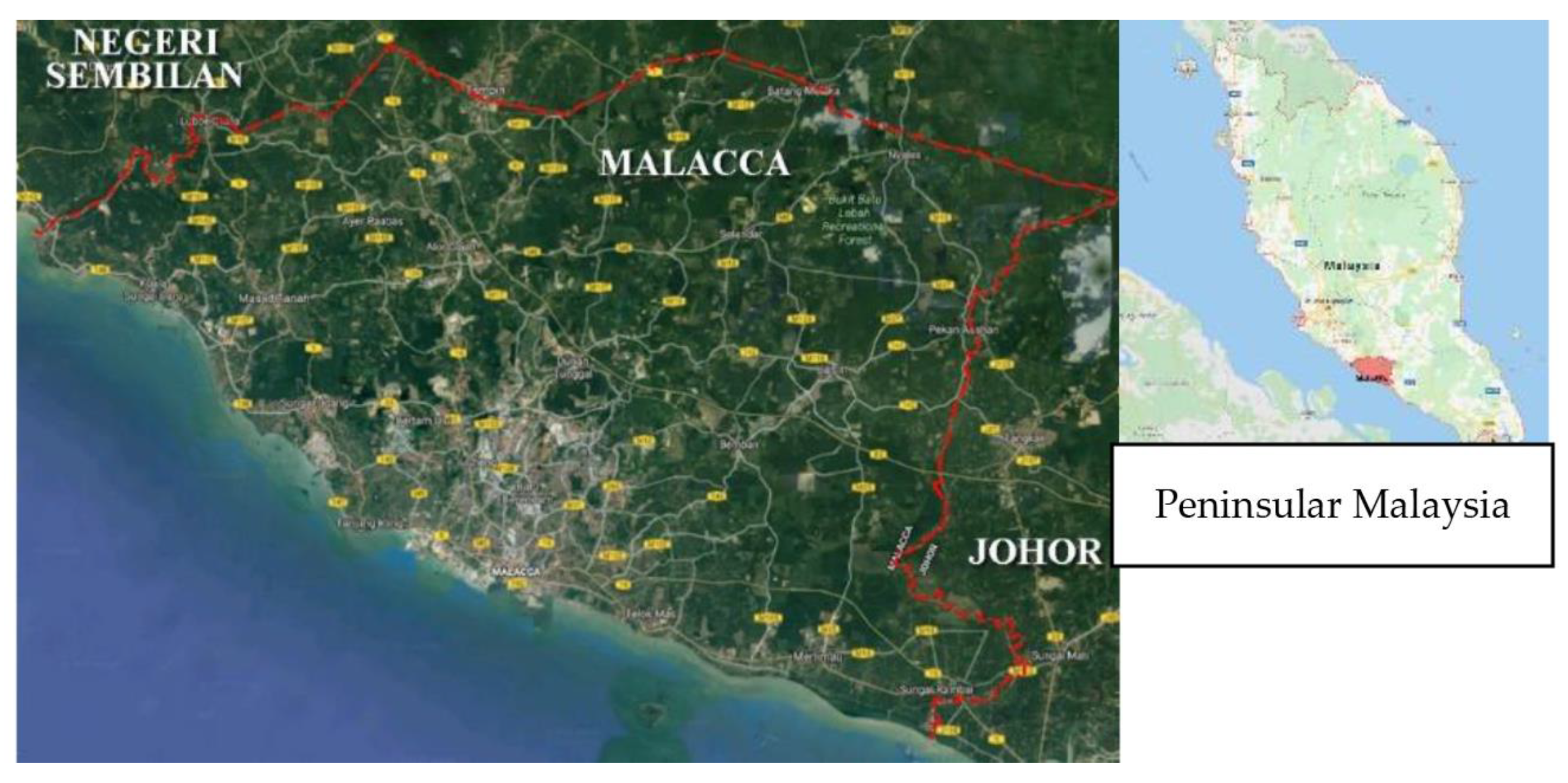

3.1. Sample and Sampling Method

3.2. Survey Instrument

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussions

- Remarkable displays of multicultural trade towns formed by the commercial exchanges of Malay, Chinese, Indian, and European cultures, as well as the influences of architecture, urban form, technology, and monumental art;

- A tangible and intangible manifestation of the colonial influences and the multicultural heritage of Asia and Europe, exemplified by the diversity of religious structures of various faiths, ethnic communities, numerous languages, worship and religious festivals, dances, costumes, art, music, food, and daily life;

- A mixture of elements that have created an unmatched architecture, culture, and urban environment in East and South Asia. Primarily the unique variety of townhouses and shophouses, each in a different stage of development.

4.1. Respondents’ Attitude, Cultural Knowledge, and Awareness of the Importance of Living Heritage

The Comparison Means of Attitude, Cultural Knowledge, and Awareness in Gender, Age Level, and Race of the Importance of Living Heritage

4.2. Respondents’ Attitude, Cultural Knowledge, and Awareness of the Participation Level

The Comparison Means of Attitude, Cultural Knowledge, and Awareness in Gender, Age Level, and Race of the Participation Level on Low, Middle, and High Levels

5. Recommendation

6. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hani, U.; Azzadina, I.; Pamatang Morgana Sianipar, C.; Setyagung, E.H.; Ishii, T. Preserving Cultural Heritage through Creative Industry: A lesson from SaungAngklungUdjo. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2012, 4, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Baroldin, N.; Mohd Din, S.A. Conservation Planning Guidelines and Design of Melaka Heritage Shophouses. Asian J. Environ.-Behav. Stud. 2018, 3, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzerini, F. Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Living Culture of Peoples. Eur. J. Int. Law 2011, 22, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujang, N. Place Attachment, and Continuity of Urban Place Identity. Asian J. Environ.-Behav. Stud. 2017, 2, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly 70/1. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1 (25 September 2015). Available online: https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/70/1 (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- UNESCO. Culture 2030 Indicators. The United Nations Educational; Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2019; Volume 7, ISBN 978-92-3-100355-4. [Google Scholar]

- ESD for 2030. Education for Sustainable Development for 2030 Toolbox; ESD: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802 (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- UNESCO Chair “Global Health and Education”. UNESCO’s Futures of Education Initiative. 2020. Available online: https://unescochair-ghe.org/2020/02/13/unescos-futures-of-education-initiative/ (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Swaniker, F. “We Need to Completely Reimagine Education”. Blog on Learning & Development. 2018. Available online: https://bold.expert/we-need-to-completely-reimagine-education (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Pillai, J. Learning with Intangible Heritage for a Sustainable Future: Guidelines for Educators in the Asia-Pacific Region; UNESCO Office. Regional Bureau for Education in Asia and the Pacific: Bangkok, Thailand, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Akagawa, N.; Smith, L. (Eds.) Safeguarding Intangible Heritage: Practices and Politics; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, N.A.A.; Ariffin, N.F.M.; Ismail, N.A.; Alias, A. The Significance of Living Heritage Conservation Education for the Community toward Sustainable Development. Environ. Behav. Proc. J. 2020, 5, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.A.A.; Ariffin, N.F.M.; Ismail, N.A.; Alias, A. The Non-formal Education Initiative of Living Heritage Conservation for the Community towards Sustainable Development. Asian J. Qual. Life 2020, 5, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabekova, A. Heritage Module within Legal Translation and Interpreting Studies: Didactic Contribution to University Students’ Sustainable Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3966. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/7/3966 (accessed on 25 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Bonnie, K.L.M.; Lewis, T.O.C.; Dennis, L.H.H. Community Participation in the Decision-Making Process for Sustainable Tourism Development in Rural Areas of Hong Kong, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Intangible Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/34299-EN.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Norzaini, A.; Sharina, A.H.; Ibrahim, K.; Norzaini, A.; Sharina, A.H.; Ibrahim, K. Integrated Public Education for Heritage Conservation: A Case for Langkawi Global Geopark. In RIMBA: Sustainable Forest Livelihoods in Malaysia and Australia; Ainsworth, G., Garnett Stephen, S., Eds.; LESTARI, UKM: Bangi, Malaysia, 2009; pp. 151–157. ISBN 978-967-5227-30-1. [Google Scholar]

- Halim, U.L.; Tambi, N. Awareness of Community on the Conservation of Heritage Buildings in George Town, Penang. J. Malays. Inst. Plan. 2021, 19, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, P.L. Community Involvement for Sustainable World Heritage Sites: The Melaka Case. Kaji. Malays. 2017, 35 (Suppl. 1), 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimah, A.A. Heritage Conservation: Authenticity and Vulnerability of Living Heritage Sites in Melaka State. Kaji. Malays. 2017, 35 (Suppl. 1), 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Conclusions and Recommendations of the Conference Linking Universal and Local Values: Managing a Sustainable Future for World Heritage; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, C. Community-Based Environmental Education, and its Participatory Process: The Case of a Forest Conservation Project in Viet Nam. Master’s Thesis, Environmental Communication and Management, Department of Urban and Rural Development, Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden, 2011; pp. 1–53. Available online: https://stud.epsilon.slu.se/3183/1/Bui_C_110828.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Maser, C. Sustainable Community Development—Principles and Concepts; St. Lucie Press: Florida, USA, 1997; Available online: https://www.biblio.com/book/sustainable-community-development-principles-concepts-maser/d/448132162 (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Uzoaru, O.C.; Ijah, C.N. Community Based Environmental Education a Strategy for Mitigating Impacts of Climate Change on Livelihood of Riverine Communities in Rivers State. Int. J. Weather. Clim. Change Conserv. Res. 2021, 7, 45–54. Available online: https://www.eajournals.org/wp-content/uploads/Community-Based-Environmental-Education.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2022).

- EPA 910-R-98-008; An EPA/USDA Partnership to Support Community-Based Education. The University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension Environmental Resources Center: Madison, WI, USA, 1998. Available online: https://naaee.org/sites/default/files/discussion_paper.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- ICCROM. Promoting People-Centered Approaches to Conservation: Living Heritage. 2015. Available online: www.iccrom.org/wp-content/uploads/PCA_Annexe-1.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Scougall, J. Lessons Learnt about Strengthening Indigenous Families and Communities; Occasional paper no. 19; Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services, and Indigenous Affairs: Canberra, Australia, 2008.

- Bell, C.; Elliott, E.; Simmons, A. Community capacity-building. In Preventing Childhood Obesity: Evidence, Policy and Practice; Waters, E., Swinburn, B., Seidell, J., Uauy, R., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2010; pp. 232–242. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.F.; Cleverly, S.; Poland, B.; Burman, D.; Edwards, R.; Robertson, A. Working with Toronto neighborhoods toward developing indicators of community capacity. Health Promot. Int. 2003, 18, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noya, A.; Clarence, E.; Craig, G. (Eds.) Community Capacity-Building: Creating a Better Future Together; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dower, J.; Bush, R. Critical Success Factors in Community Capacity-Building Centre for Primary Health Care; The University of Queensland: Brisbane, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Noor Fazamimah, M.A. Willingness-To-Pay Value of Cultural Heritage and Its Management for Sustainable Conservation of George Town, World Heritage Site. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Built Environment, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kamamba, D.M.K. The Challenges of Sustainable Cultural Heritage/Community Tourism; Second African Peace Through Tourism, Golden Tulip Hotel: Dar es Salaam City, United Republic of Tanzania, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J.; Boyd, S.W. Heritage Tourism; Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Petronela, T. The importance of intangible cultural heritage in the economy. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 39, 731–736. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212567116302714 (accessed on 15 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.-K.; Tan, S.-H.; Kok, Y.-S.; Choon, S.-W. Sense of place and sustainability of intangible cultural heritage—The case of George Town and Melaka. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 376–387. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0261517718300360 (accessed on 15 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- Ounanian, K.; van Tatenhove, J.P.M.; Hansen, C.J.; Delaney, A.E.; Bohnstedt, H.; Azzopardi, E.; Flannery, W.; Toonen, H.; Kenter, J.O.; Ferguson, L.; et al. Conceptualizing coastal and maritime cultural heritage through communities of meaning and participation. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 212, 105806. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0964569121002891 (accessed on 15 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S. Cultural Heritage as a Tool for Peace: A Case of Sudan. In Proceedings of the ICOMOS 19th General Assembly and Scientific Symposium “Heritage and Democracy”, New Delhi, India, 13–14 December 2017; Available online: http://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/2006/1/33._ICOA_990_Agarwal_SM.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- UNESCO. Information Sheet: Policy Provisions for Social Cohesion and Peace. 2014. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/Social_cohesion_and_peace_EN.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzuki, A.; Hay, I. Towards a public participation framework in tourism planning. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2013, 10, 494–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J. The many interpretations of participation. Focus 1995, 16, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, C. Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. J. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cole, S.T.; Chancellor, C.H. Residents’ preferences for involvement in tourism development and influences from individual profiles. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2013, 10, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. Towards a typology of community participation in the tourism development process. Anatolia 1999, 10, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Mastura, J.A.; Ghafar, A.; Rabeeh, B. Community participation in World Heritage Site conservation and tourism development. J. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Inclusive and Sustainable Urban Planning: A Guide for Municipalities; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- King, C.S.; Feltey, K.M.; Susel, B.O.N. The question of participation: Toward authentic public participation in public administration. Public Adm. Rev. 1998, 58, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.E. Consensus building: Clarifications for the critics. Plan. Theory 2004, 3, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George Town World Heritage Incorporated and Penang Education Association. Cultural Heritage Education Program (CHEP) Booklet. 2018. Available online: https://issuu.com/arts-ed.penang/docs/chep_booklet_april_2_2018 (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Singapore National Heritage Board. Heritage Education Highlights. 2020. Available online: https://www.nhb.gov.sg/-/media/nhb/images/education/ (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- The International Research Centre for ICH in the Asia-Pacific Region, under the auspices of UNESCO, and the National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Multi-Disciplinary Study on Intangible Cultural Heritage’s Contribution to Sustainable Development, 2019, Focusing on Education: A Guide for Facilitators and Local Coordinators for a School a Living Traditions on Buklog of Thanksgiving Ritual of the Subanen, Philippines. Available online: https://www.irci.jp/wp_files/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Guideline_F.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- The Creative Europe Program of the European Union. Heritage Hubs: Manual for Cultural Heritage Education. 2020. Available online: https://heritagehubs.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/HH-Manual-Inglese-Web-rev2.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Aziz, N.A.A.; Ariffin, N.F.M.; Ismail, N.A.; Ismail, S.; Alias, A.; Utaberta, N. The Comparison of the Best Practices of the Community-Based Education for Living Heritage Site Conservation. In Sustainable Architecture and Building Environment; Yola, L., Nangkula, U., Ayegbusi, O.G., Awang, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; Volume 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Sustainable Communities. What Is a Sustainable Community? Available online: https://sustain.org/about/what-is-a-sustainable-community/ (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Simon Fraser University. What is Sustainable Development? Available online: https://www.sfu.ca/sustainabledevelopment/Archives/what-is-sustainable-community-development.html (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- RideShark Corporation. INFOGRAPHIC: The Key Components of Sustainable Communities. Available online: https://www.rideshark.com/2017/07/19/sustainablecommunities/ (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Community First Oxfordshire. Sustainable Communities: Community Action. Available online: https://www.communityfirstoxon.org/community-action-and-volunteering/community-action/sustainable-communities/ (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- United Kingdom Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government. What Is a Sustainable Community? Living Geography: Building Sustainable Communities. Geographical Association and Academy for Sustainable Communities. 2005. Available online: www.communities.gov.uk/index.asp?id=1139866 (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Andrews, E.; Stevens, M.; Wise, G. Chapter 10: A model of community-based environmental education. In New Tools for Environmental Protection: Education, Information, and Voluntary Measures; Dietz, T., Stern, T., Eds.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 161–182. Available online: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/10401/chapter/11#164 (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Suhardi, M. Seremban Urban Park, Malaysia: A Preference Study; Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University: Blacksburg, Virginia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Md Nor, A.B. Statistical Methods in Research; Prentice-Hall: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Statistics Malaysia Official Portal. Population Size and Annual Population Growth Rate. Available online: https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php? (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Pallant, J. SPSS survival manual. In A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS for Windows, 3rd ed.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2007; ISBN 0335223664. [Google Scholar]

- Hami, A.; Suhardi, M.; Manohar, M.; Shahhosseini, H. Users’ Preferences of Usability and Sustainability of old Urban Park in Tabriz, Iran. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2011, 5, 1899–1905. [Google Scholar]

- Hami, A.; Sreetheran, M. Public perception and perceived landscape function of urban park trees in Tabriz. Iran. Landsc. Online 2018, 62, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results, and Higher Acceptance. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Melaka and Georgetown, are Historic Cities of the Straits of Malacca. 2008. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1223 (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. Melaka—Estimated Population by Ethnic Group 2020. Available online: https://cloud.stats.gov.my/index.php/s/sOkaT3J0lLbNIBd (accessed on 25 December 2022).

- Ackerman, P.L.; Bowen, K.R.; Beier, M.E.; Kanfer, R. Determinants of individual differences and gender differences in knowledge. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 93, 797–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, R.; Irwing, P. Sex differences in general knowledge, semantic memory, and reasoning ability. Br. J. Psychol. 2002, 93, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, R.; Irwing, P.; Cammock, T. Sex differences in general knowledge. Intelligence 2002, 30, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tore, B. Role Participation: A Comparison across Age Groups in a Norwegian General Population Sample. Occup. Ther. Int. 2018, 2018, 8680915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Contribution Category | Finding | Author | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNESCO, 2015 [16] | Petronela, 2016 [35] | S.-K. Tan et al., 2018 [36] | Ounanian, K. et al., 2021 [37] | Agarwal, S., 2018 [38] | UNESCO 2014 [39] | ||

| Inclusive Social Development | Intangible cultural heritage is vital to achieving food security. | 🗸 | |||||

| Traditional health practices can contribute to the well-being and Inclusive quality of health care for all. | 🗸 | ||||||

| Traditional practices concerning water management can contribute to equitable access to clean water and sustainable water use. | 🗸 | ||||||

| Intangible cultural heritage provides living examples of educational content and method. | 🗸 | ||||||

| Intangible cultural heritage can help strengthen social cohesion and inclusion. | 🗸 | ||||||

| Intangible cultural heritage is decisive in creating and transmitting gender roles and identities and, therefore, critical for gender equality. | 🗸 | ||||||

| Intangible cultural heritage as a place attachment, sense of place, and place identity. | 🗸 | ||||||

| Sense of loss when a lack of transmission of intangible cultural heritage knowledge and skills. | 🗸 | ||||||

| Environmental Sustainability | Intangible cultural heritage can help protect biodiversity. | 🗸 | 🗸 | ||||

| Intangible cultural heritage can contribute to environmental sustainability. | 🗸 | 🗸 | |||||

| Local knowledge and practices concerning nature can contribute to the research on environmental sustainability. | 🗸 | 🗸 | |||||

| Knowledge and coping strategies often provide a foundation for community-based resilience to natural disasters and climate change. | 🗸 | 🗸 | |||||

| Inclusive Economic Development | Intangible cultural heritage is often essential to sustaining the livelihoods of groups and communities. | 🗸 | 🗸 | ||||

| Intangible cultural heritage can generate revenue and decent work for many people and individuals, including poor and vulnerable ones. | 🗸 | 🗸 | |||||

| Intangible cultural heritage, as a living heritage, can be a significant source of innovation for development. | 🗸 | 🗸 | |||||

| Communities can also benefit from tourism activities related to intangible cultural heritage. | 🗸 | 🗸 | |||||

| Peace & Security | Many intangible cultural heritage practices promote peace at their very core. | 🗸 | 🗸 | ||||

| Intangible cultural heritage can help to prevent or resolve disputes. | 🗸 | ||||||

| Intangible cultural heritage can contribute to restoring peace and security. | 🗸 | 🗸 | 🗸 | ||||

| Protecting intangible cultural heritage is also a means to lasting peace and security. | 🗸 | 🗸 | |||||

| Intangible cultural heritage in conflict-related emergencies. | 🗸 | ||||||

| Type | Coercive Participation | Induced Participation | Spontaneous Participation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components | ||||

| Level of Participation | Low level/Passive | Middle level/Responsive | High level/Active | |

| Involvement | Negligible involvement (limited) | Passive involvement | Active involvement | |

| Action | No actual power to make the decision and to control the development process. | No actual power to make decisions and control the development process. | Have the power to make decisions and control the development process. | |

| Time involvement | Just get the information. | Usually, happen after development. | Early planning stage. | |

| Input | Government, authorities, and the private sector exert their control. | Public hearing or community consultation. | Residents can generate trust, ownership, and social capital. | |

| Constructs | No. of Items | Alpha (α) |

|---|---|---|

| Participation level | 6 | 0.882 |

| Importance of LH | 10 | 0.944 |

| Ethnic Group | 2020 | Sample Size Data Collection | Actual Data Collection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage (%) | Population | |||

| Malay | 71.7 | 715,872.9 | 275 | 268 |

| Chinese | 22.1 | 220,652.6 | 85 | 50 |

| Indian | 5.6 | 55,912.0 | 22 | 13 |

| Others | 0.6 | 5990.6 | 2 | 61 |

| Total | 100 | 998,428 | 384 | 392 |

| Demographic | Variable | Frequency | Percentages % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 193 | 49.2 |

| Female | 199 | 50.8 | |

| Age Level | 15–24 | 79 | 20.2 |

| 25–34 | 98 | 25.0 | |

| 35–44 | 85 | 21.7 | |

| 45–54 | 94 | 24.0 | |

| 55–64 | 36 | 9.2 | |

| Race | Malay | 268 | 68.4 |

| Chinese | 50 | 12.8 | |

| Indian | 13 | 3.3 | |

| Others | 61 | 15.6 |

| Importance of LH | Code | Variable | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social: SC | SC1 | The cultural heritage in Melaka as my image, identity, and pride. | 4.32 | 0.86 |

| SC2 | The loss of cultural heritage caused losses to the community in Melaka. | 4.36 | 0.84 | |

| SC3 | I am responsible for practicing my cultural heritage for its continuity in the future. | 4.14 | 0.90 | |

| SC4 | The continuity of heritage culture terminates when there is a lack of transmission. | 4.20 | 0.82 | |

| Economic: EC | EC1 | Knowledge, skills, and cultural heritage practices contribute to economic improvement and living standards. | 4.14 | 0.85 |

| EC2 | The originality of the culture is lost, and natural resources are destroyed when there is a lack of awareness in the new development management. | 4.22 | 0.83 | |

| Environmental: EN | EN1 | Knowledge and practice of cultural heritage accumulated overtime to make sustainable use of natural resources and minimize the impact of climate change. | 3.97 | 0.92 |

| EN2 | The cultural heritage in Melaka contributes to the continuity between the past, present, and Future in the environment setting. | 4.33 | 0.84 | |

| Peace & Security: PS | PS1 | Appreciation and understanding of cultural differences between communities create harmony in daily life. | 4.27 | 0.81 |

| PS2 | An unpeaceful environment occurs when there is a lack of understanding of cultural differences in the community. | 4.18 | 0.83 |

| N | SC1 | SC2 | SC3 | SC4 | SC | EC1 | EC2 | EC | EN1 | EN2 | EN | PS1 | PS2 | PS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 392 | 4.32 | 4.36 | 4.14 | 4.20 | 4.25 | 4.14 | 4.22 | 4.18 | 3.97 | 4.33 | 4.15 | 4.27 | 4.18 | 4.23 |

| Gender | |||||||||||||||

| Male | 193 | 4.31 | 4.33 | 4.09 | 4.21 | 4.24 | 4.10 | 4.24 | 4.17 | 3.91 | 4.31 | 4.11 | 4.26 | 4.13 | 4.20 |

| Female | 199 | 4.33 | 4.39 | 4.18 | 4.19 | 4.27 | 4.18 | 4.21 | 4.19 | 4.04 | 4.36 | 4.20 | 4.29 | 4.22 | 4.25 |

| Age Level | |||||||||||||||

| 15–24 | 79 | 4.28 | 4.23 | 4.03 | 4.16 | 4.17 | 4.11 | 4.10 | 4.11 | 3.94 | 4.19 | 4.06 | 4.22 | 4.09 | 4.15 |

| 25–34 | 98 | 4.14 | 4.32 | 4.03 | 4.19 | 4.17 | 4.12 | 4.26 | 4.19 | 3.92 | 4.18 | 4.05 | 4.19 | 4.09 | 4.14 |

| 35–44 | 85 | 4.33 | 4.38 | 4.21 | 4.31 | 4.31 | 4.19 | 4.25 | 4.22 | 3.96 | 4.40 | 4.18 | 4.29 | 4.25 | 4.27 |

| 45–54 | 94 | 4.43 | 4.46 | 4.17 | 4.12 | 4.29 | 4.10 | 4.19 | 4.14 | 4.03 | 4.48 | 4.26 | 4.27 | 4.18 | 4.22 |

| 55–64 | 36 | 4.58 | 4.47 | 4.39 | 4.28 | 4.43 | 4.22 | 4.42 | 4.32 | 4.08 | 4.50 | 4.29 | 4.58 | 4.44 | 4.51 |

| Race | |||||||||||||||

| Malay | 268 | 4.35 | 4.45 | 4.16 | 4.31 | 4.32 | 4.21 | 4.30 | 4.26 | 4.04 | 4.40 | 4.22 | 4.31 | 4.25 | 4.28 |

| Chinese | 50 | 4.16 | 4.22 | 4.00 | 3.98 | 4.09 | 4.00 | 4.10 | 4.05 | 4.00 | 4.16 | 4.08 | 4.08 | 4.08 | 4.08 |

| Indian | 13 | 4.23 | 3.85 | 4.00 | 3.92 | 4.00 | 4.15 | 4.23 | 4.19 | 3.62 | 4.00 | 3.81 | 4.23 | 3.85 | 4.04 |

| Others | 61 | 4.33 | 4.20 | 4.15 | 3.95 | 4.16 | 3.92 | 3.97 | 3.94 | 3.74 | 4.26 | 4.00 | 4.28 | 4.00 | 4.14 |

| Participation Level | Code | Variable | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low: L (Information) | L1 | I get involved and keep up with the news regarding this conservation. | 3.01 | 1.11 |

| L2 | I am familiar with this conservation. | 2.83 | 1.08 | |

| Middle: M (Collaboration) | M1 | I receive information and do what local authorities and state government officials ask. | 2.98 | 1.17 |

| M2 | I meet with local authorities and state government officials to discuss the issues. | 2.51 | 1.17 | |

| High: H (Decision Making) | H1 | I am interested in volunteering and participating from the beginning until the end. | 3.18 | 1.20 |

| H2 | I in my community have the power to change the decisions taken by local authorities and state government officials. | 2.77 | 1.31 |

| N | L1 | L2 | L | M1 | M2 | M | H1 | H2 | H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 392 | 3.01 | 2.83 | 2.92 | 2.98 | 2.51 | 2.75 | 3.18 | 2.77 | 2.97 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 193 | 2.98 | 2.83 | 2.91 | 2.96 | 2.53 | 2.75 | 3.21 | 2.80 | 3.00 |

| Female | 199 | 3.04 | 2.83 | 2.94 | 3.01 | 2.48 | 2.74 | 3.15 | 2.73 | 2.94 |

| Age Level | ||||||||||

| 15–24 | 79 | 3.23 | 2.99 | 3.11 | 3.13 | 2.63 | 2.88 | 3.63 | 3.11 | 3.37 |

| 25–34 | 98 | 2.99 | 2.87 | 2.93 | 3.12 | 2.62 | 2.87 | 3.24 | 2.88 | 3.06 |

| 35–44 | 85 | 3.14 | 2.86 | 3.00 | 3.12 | 2.68 | 2.90 | 3.34 | 2.78 | 3.06 |

| 45–54 | 94 | 2.79 | 2.63 | 2.71 | 2.68 | 2.21 | 2.45 | 2.72 | 2.44 | 2.58 |

| 55–64 | 36 | 2.89 | 2.89 | 2.89 | 2.78 | 2.28 | 2.53 | 2.78 | 2.53 | 2.65 |

| Race | ||||||||||

| Malay | 268 | 3.05 | 2.86 | 2.95 | 3.10 | 2.57 | 2.84 | 3.32 | 2.81 | 3.07 |

| Chinese | 50 | 3.04 | 2.88 | 2.96 | 2.84 | 2.44 | 2.64 | 3.28 | 3.00 | 3.14 |

| Indian | 13 | 3.00 | 2.92 | 2.96 | 3.15 | 2.54 | 2.85 | 3.15 | 2.85 | 3.00 |

| Others | 61 | 2.84 | 2.67 | 2.75 | 2.54 | 2.26 | 2.40 | 2.44 | 2.34 | 2.39 |

| Participation Level | Importance of LH | |

|---|---|---|

| Participation level | 1 | 0.254 ** |

| Importance of LH | 0.254 ** | 1 |

| The Importance of LH | Participation Level | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Focused more on the male gender. | Focused more on the male gender. |

| Age Level | More focused on a middle-aged level group of 15–24, 25–34, and 35–44 to increase cultural knowledge and awareness. | Focused on the age level groups 45–55 and 55–64. Creating more interesting activities and interactive education. |

| Race | The Indian race needs to focus on environmental contributions meanwhile other races in economic contributions. | Every variable in participation level in the race must be highlighted, especially in other races. |

| Overall | The EN1 variable must be highlighted in every gender, age, and race group the importance of LH to increase cultural knowledge and awareness. | The L2 and M2 variable must be highlighted in every gender, age, and race group of the participation level, especially the middle level (collaboration). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdul Aziz, N.A.; Mohd Ariffin, N.F.; Ismail, N.A.; Alias, A. Community Participation in the Importance of Living Heritage Conservation and Its Relationships with the Community-Based Education Model towards Creating a Sustainable Community in Melaka UNESCO World Heritage Site. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1935. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031935

Abdul Aziz NA, Mohd Ariffin NF, Ismail NA, Alias A. Community Participation in the Importance of Living Heritage Conservation and Its Relationships with the Community-Based Education Model towards Creating a Sustainable Community in Melaka UNESCO World Heritage Site. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):1935. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031935

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdul Aziz, Noor Azramalina, Noor Fazamimah Mohd Ariffin, Nor Atiah Ismail, and Anuar Alias. 2023. "Community Participation in the Importance of Living Heritage Conservation and Its Relationships with the Community-Based Education Model towards Creating a Sustainable Community in Melaka UNESCO World Heritage Site" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 1935. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031935

APA StyleAbdul Aziz, N. A., Mohd Ariffin, N. F., Ismail, N. A., & Alias, A. (2023). Community Participation in the Importance of Living Heritage Conservation and Its Relationships with the Community-Based Education Model towards Creating a Sustainable Community in Melaka UNESCO World Heritage Site. Sustainability, 15(3), 1935. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031935