Examining the Interaction between Perceived Cultural Tightness and Prevention Regulatory Focus on Life Satisfaction in Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Tightness–Looseness

1.2. Prevention Regulatory Focus

1.3. Satisfaction with Life

1.4. The Present Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants, Design, and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations (UN): New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; Daly, L.; Fioramonti, L.; Giovannini, E.; Kubiszewski, I.; Mortensen, L.F.; Pickett, K.E.; Ragnarsdotti, K.V.; De Vogli, R.; Wilkinson, R. Modelling and measuring sustainable wellbeing in connection with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 130, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Tay, L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gable, S.L.; Haidt, J. What (and why) is positive psychology? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2005, 9, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IJzerman, H.; Lewis, N.A.; Przybylski, A.K.; Weinstein, N.; DeBruine, L.; Ritchie, S.J.; Vazire, S.; Forscher, P.S.; Morey, R.D.; Ivory, J.D.; et al. Use caution when applying behavioural science to policy. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 1092–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marco, M.; Baker, M.L.; Daszak, P.; De Barro, P.; Eskew, E.A.; Godde, C.M.; Harwood, T.D.; Herrero, M.; Hoskins, A.J.; Johnson, E.; et al. Sustainable development must account for pandemic risk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 3888–3892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bavel, J.J.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N.; et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, M.J. Rule Makers, Rule Breakers: Tight and Loose Cultures and the Secret Signals That Direct Our Lives; Scribner Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand, M.J.; Raver, J.L.; Nishii, L.; Leslie, L.M.; Lun, J.; Lim, B.C.; Duan, L.; Almaliach, A.; Ang, S.; Arnadottir, J.; et al. Differences between Tight and Loose Cultures: A 33-Nation Study. Science 2011, 332, 1100–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, J.R.; Gelfand, M.J. Tightness-looseness across the 50 united states. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7990–7995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.C.; van Egmond, M.; Choi, V.K.; Ember, C.R.; Halberstadt, J.; Balanovic, J.; Basker, I.N.; Boehnke, K.; Buki, N.; Fischer, R.; et al. Ecological and cultural factors underlying the global distribution of prejudice. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrotti, J.T.; Edwards, L.M.; Lopez, S.J. Positive psychology within a cultural context. In Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology, 2nd ed.; Lopez, S.J., Snyder, C.R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 2, pp. 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. Suicide: A Study in Sociology; Spaulding, J.A.; Simpson, G., Translators; Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm, E. Escape from Freedom; Holt, Rinehart &Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Geeraert, N.; Li, R.; Ward, C.; Gelfand, M.; Demes, K.A. A tight spot: How personality moderates the impact of social norms on sojourner adaptation. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 30, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulmer, C.A.; Gelfand, M.J.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Diener, E.; Pierro, A.; Higgins, E.T. On “feeling right” in cultural contexts: How person-culture match affects self-esteem and subjective well-being. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 1563–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Beyond pleasure and pain. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, E.T. Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 1998; Volume 30, pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelto, P. The difference between “tight” and “loose” societies. Trans. Actions 1968, 5, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, M.J.; Nishii, L.H.; Raver, J.L. On the nature and importance of cultural tightness-looseness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1225–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Regulatory focus theory. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 483–504. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, E.T. Making a good decision: Value from fit. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 1217–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, E.T. Value from regulatory fit. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2005, 14, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, A.W.; Pierro, A.; Higgins, E.T. Regulatory mode and preferred leadership styles: How fit increases job satisfaction. Basic Appl. Soc. Psych. 2007, 29, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, C.D.; Higgins, E.T. Shared reality: How social verification makes the subjective objective. In Handbook of Motivation and Cognition, Vol. 3. The Interpersonal Context; Sorrentino, R.M., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 28–84. [Google Scholar]

- De Leersnyder, J.; Kim, H.S.; Mesquita, B. My emotions belong here and there: Extending the phenomenon of emotional acculturation to heritage culture fit. Cogn. Emot. 2020, 34, 1573–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, P.; Gelfand, M.J.; Nau, D.; Lun, J. Societal threat and cultural variation in the strength of social norms: An evolutionary basis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2015, 129, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, J.R.; Boski, P.; Gelfand, M.J. Culture and National Well-Being: Should Societies Emphasize Freedom or Constraint? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Santo, D.; Talamo, A.; Bonaiuto, F.; Cabras, C.; Pierro, A. A multilevel Analysis of the Impact of Unit Tightness vs. Looseness Culture on Attitudes and Behaviors in the Workplace. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 652068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T.; Ronald, S.F.; Robert, E.H.; Lorraine, C.I.; Ozlem, N.A.; Amy, T. Achievement Orientations from Subjective Histories of Success: Promotion Pride versus Prevention Pride. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 31, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychol. Rev. 1987, 94, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kark, R.; Katz-Navon, T.; Delegach, M. The dual effects of leading for safety: The mediating role of employee regulatory focus. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1332–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamstra, M.R.W.; Van Yperen, N.W.; Wisse, B.; Sassenberg, K. Transformational-transactional leadership styles and followers’ regulatory focus. J. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 10, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manczak, E.M.; Zapata-Gietl, C.; McAdams, D.P. Regulatory focus in the life story: Prevention and promotion as expressed in three layers of personality. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 106, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Fan, W.; Tan, Q.; Zhong, Y. People higher in self-control do not necessarily experience more happiness: Regulatory focus also affects subjective well-being. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 86, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, F.M.; Withey, S.B. Social Indicators of Well-Being: America’s Perception of Life Quality; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Bradburn, N.M. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Kammann, R.; Flett, R. Affectometer 2: A scale to measure current level of general happiness. Austin J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 1983, 35, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma, A.; Stones, M.J. The measurement of happiness: Development of the Memorial University of Newfoundland Scale of Happiness (MUNSCH). J. Geo-Inf. Sci. 1980, 35, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psych. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, J.F.M.; Franks, B.; Higgins, E.T. Shared reality makes life meaningful: Are we really going in the right direction? Motiv. Sci. 2017, 3, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, H.; Higgins, E.T. Optimism, promotion pride, and prevention pride as predictors of quality of life. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 1521–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddiener.com. Available online: https://eddiener.com/scales/7 (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Pavot, W.; Diener, E. Review of the Satisfaction with Life Scale. Psychol. Assess. 1993, 5, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis [Internet]. 2018. Available online: www.guilford.com/ebooks (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Gelfand, M.J.; Jackson, J.C.; Pan, X.; Nau, D.; Pieper, D.; Denison, E.; Dagher, M.; Van Lange, P.A.; Chiu, C.Y.; Wang, M. The relationship between cultural tightness–looseness and COVID-19 cases and deaths: A global analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e135–e144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, P.B.; Lee, G. Predicting hospitality employees’ safety performance behaviors in the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldner, C.; Di Santo, D.; Viola, M.; Pierro, A. Perceived COVID-19 threat and reactions to noncompliant health-protective behaviors: The mediating role of desired cultural tightness and the moderating role of age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.G. A Monte Carlo study of the effects of correlated method variance in moderated regression analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1985, 36, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, G.H.; Judd, C.M. Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 114, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Silver, S.R.; Randolph, W.A. Taking empowerment to the next level: A multiple-level model of empowerment, performance, and satisfaction. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 332–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Yam, K.C.; Chen, C.; Li, W.; Dong, X. Talking about COVID-19 is positively associated with team cultural tightness: Implications for team deviance and creativity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 106, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, R.S.; Förster, J. The effects of promotion and prevention cues on creativity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 1001–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacramento, C.A.; Fay, D.; West, M.A. Workplace duties or opportunities? Challenge stressors, regulatory focus, and creativity. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2013, 121, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived Cultural Tightness | (0.76) | 3.71 | 0.76 | ||

| 2. Prevention Regulatory Focus | 0.07 | (0.74) | 3.20 | 0.82 | |

| 3. Life Satisfaction | 0.12 * | 0.27 ** | (0.85) | 4.60 | 1.15 |

| b | se | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.007 |

| Gender | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.023 |

| Education | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.007 |

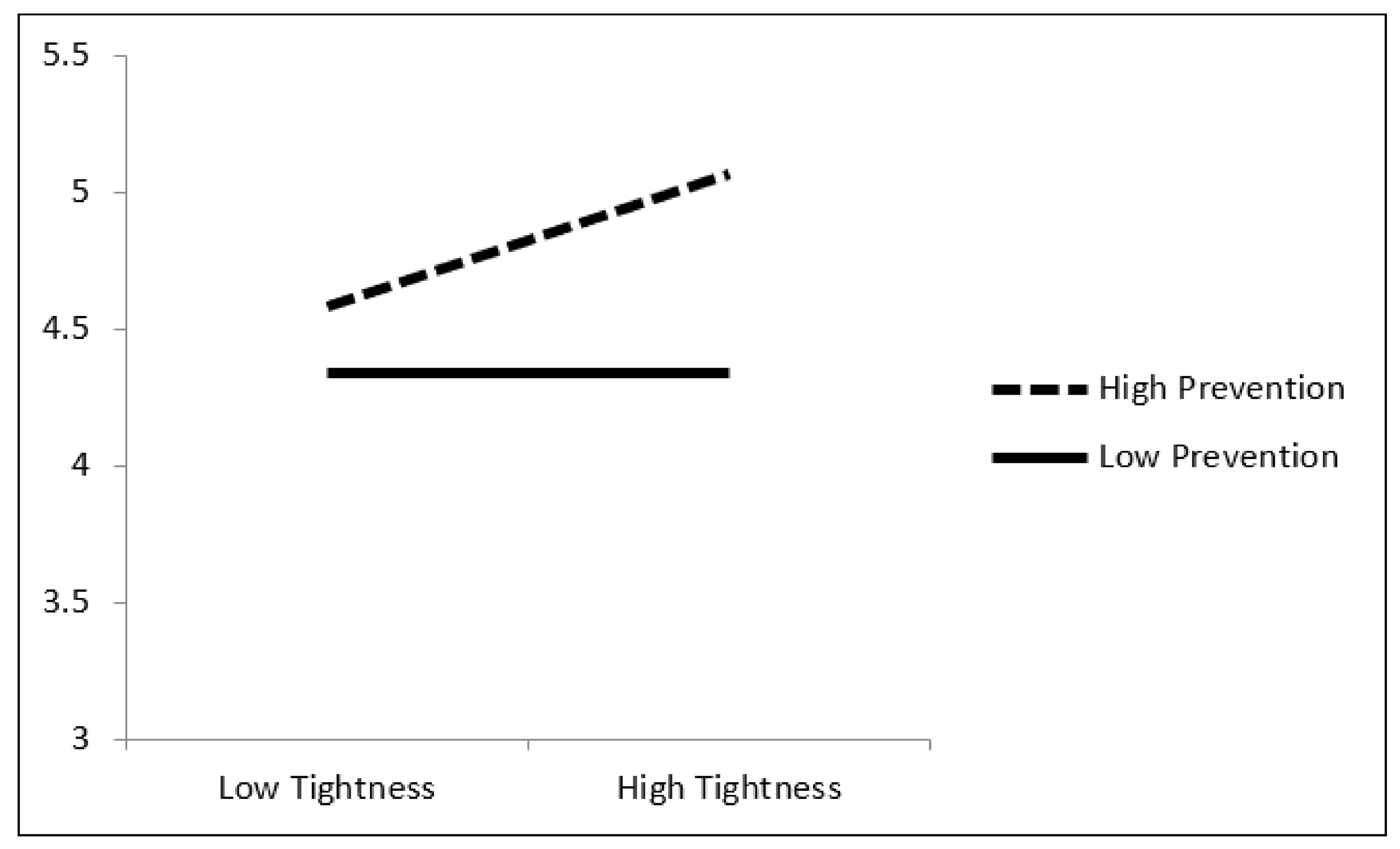

| Perceived Cultural Tightness | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.014 |

| Prevention Regulatory Focus | 0.30 | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Tightness x Prevention | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.017 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Contu, F.; Di Santo, D.; Baldner, C.; Pierro, A. Examining the Interaction between Perceived Cultural Tightness and Prevention Regulatory Focus on Life Satisfaction in Italy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1865. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031865

Contu F, Di Santo D, Baldner C, Pierro A. Examining the Interaction between Perceived Cultural Tightness and Prevention Regulatory Focus on Life Satisfaction in Italy. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):1865. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031865

Chicago/Turabian StyleContu, Federico, Daniela Di Santo, Conrad Baldner, and Antonio Pierro. 2023. "Examining the Interaction between Perceived Cultural Tightness and Prevention Regulatory Focus on Life Satisfaction in Italy" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 1865. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031865

APA StyleContu, F., Di Santo, D., Baldner, C., & Pierro, A. (2023). Examining the Interaction between Perceived Cultural Tightness and Prevention Regulatory Focus on Life Satisfaction in Italy. Sustainability, 15(3), 1865. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031865