Do Dynamic Capabilities and Digital Transformation Improve Business Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Insights from Beekeeping MSMEs in Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

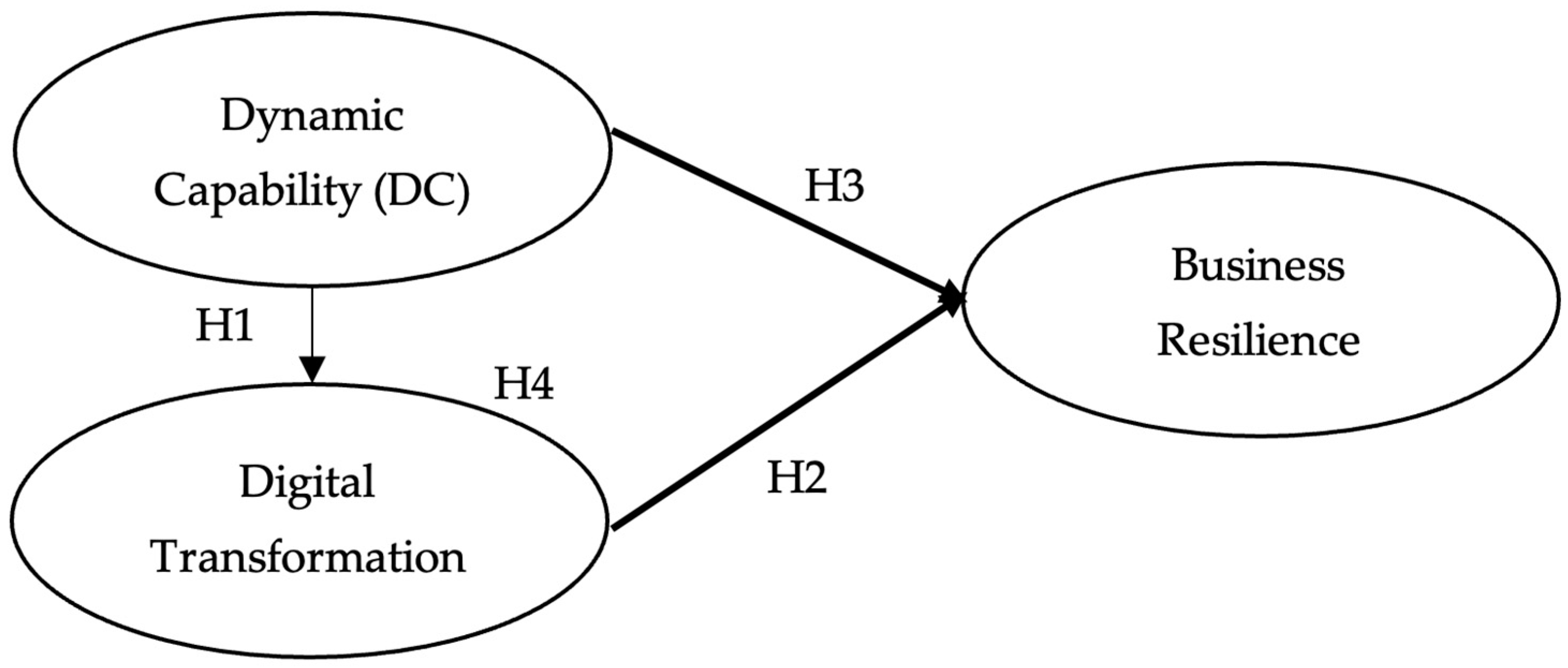

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. The Link between Dynamic Capabilities (DC) and Digital Transformation (DT)

2.2. The Link between Digital Transformation (DT) and Business Resilience

2.3. The Link between Dynamic Capability (DC) Dan Business Resilience

2.4. The Role of DT as a Mediator Variable

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measurement of Research Variables

3.2. Questionnaire Development

3.3. Participants

- Grouping business size and business model

- The numbers of samples for each size are different according to empirical conditions

- The total sample of 388 beekeeping MSMEs based on the empirical data are as follows: 78 micro-FB respondents, 217 small-FB respondents, 37 small-NFB respondents, and 56 medium-FB respondents.

4. Results

4.1. Validity and Reliability Analyses

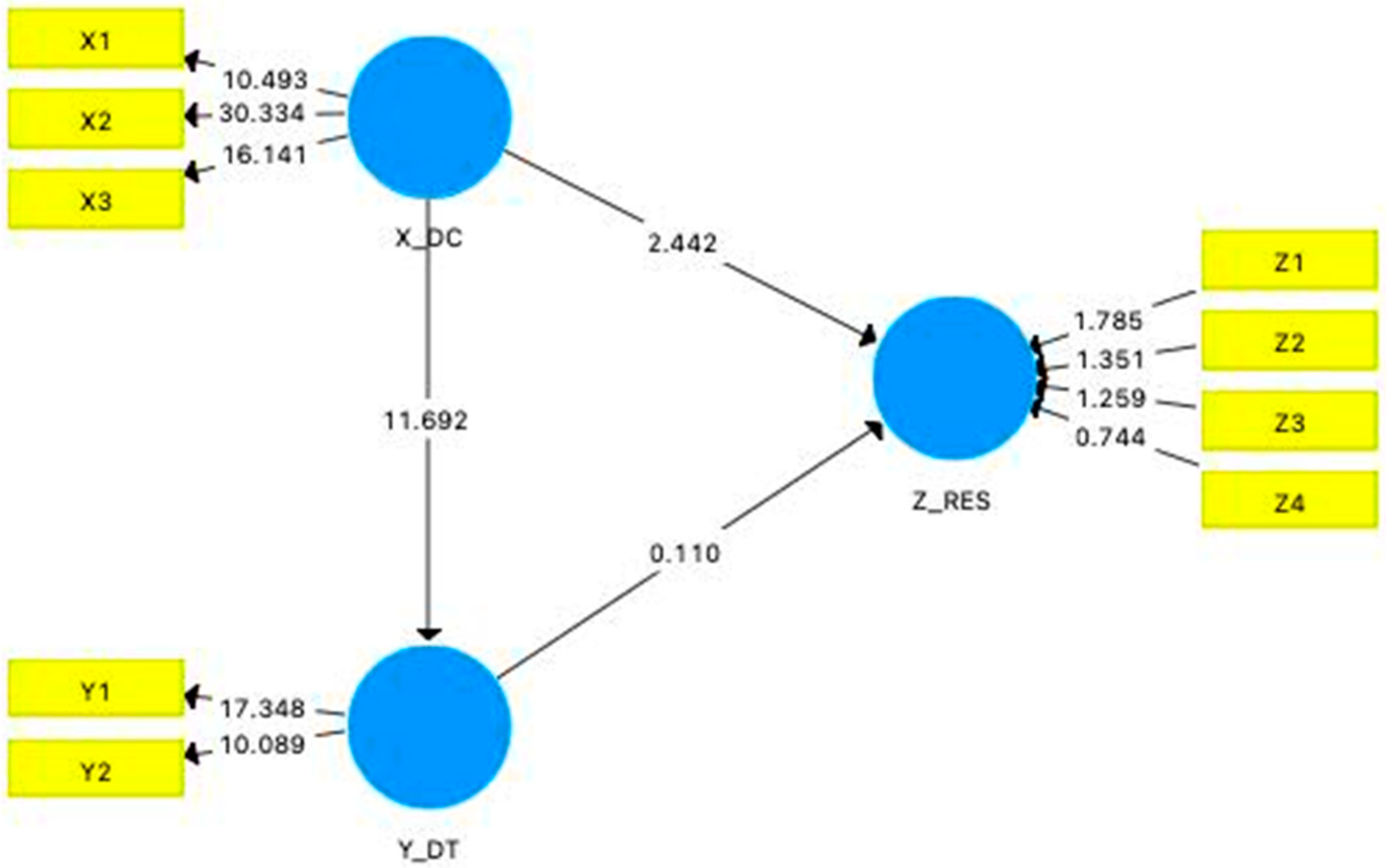

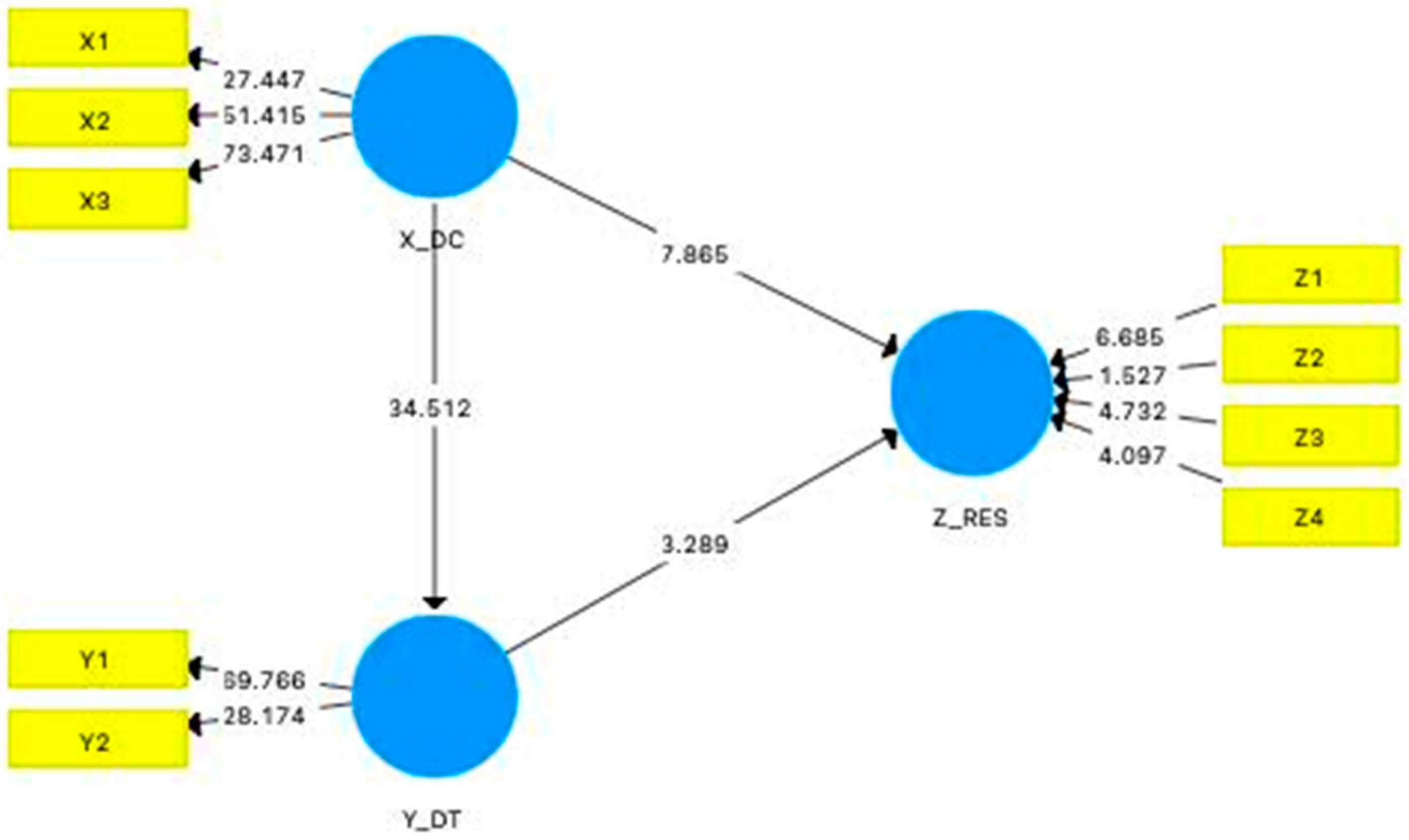

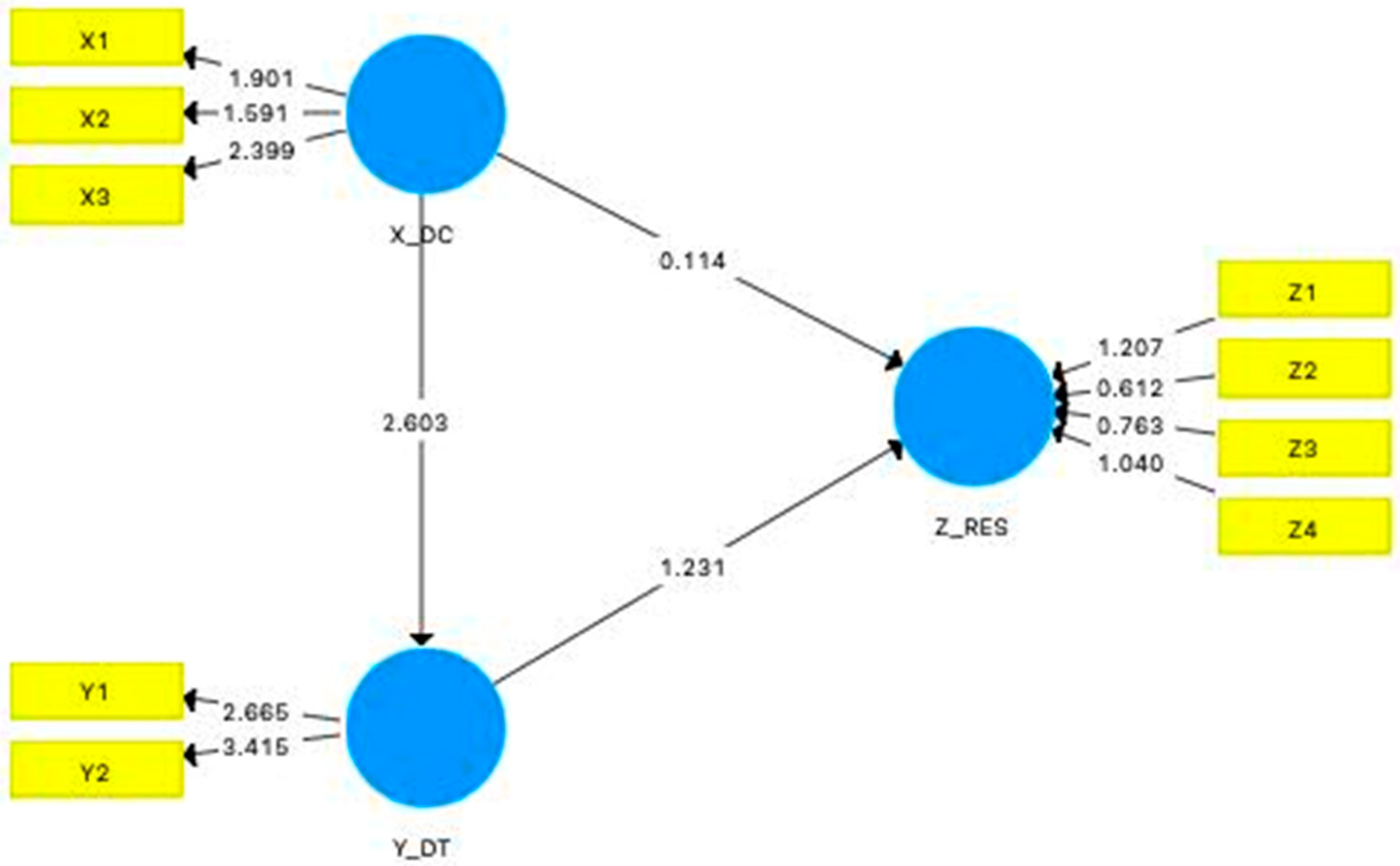

4.2. Structural Measurement Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Micro-FB

5.2. Small-FB

5.3. Small-NFB

5.4. Medium-FB

5.5. Theoretical Contributions

5.6. Practical Implications

5.7. Limitation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Belitski, M.; Guenther, C.; Kritikos, A.S.; Thurik, R. Economic Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Entrepreneurship and Small Businesses. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 58, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.H.; Fisch, C.; Hirschmann, M. The Determinants of Bootstrap Financing in Crises: Evidence from Entrepreneurial Ventures in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 58, 867–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, S.; Miryugin, F. Pandemics and Firms: Drawing Lessons from History. Int. Financ. 2021, 24, 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Fu, M.; Pan, H.; Yu, Z.; Chen, Y. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Firm Performance. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2020, 56, 2213–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toiba, H.; Efani, A.; Rahman, M.S.; Nugroho, T.W.; Retnoningsih, D. Does the COVID-19 Pandemic Change Food Consumption and Shopping Patterns? Evidence from Indonesian Urban Households. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2022, 49, 1803–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Zhang, W.-W.; Dinca, M.S.; Raza, M. Determining the Impact of COVID-19 on the Business Norms and Performance of SMEs in China. Econ. Res. -Ekon. Istraživanja 2022, 35, 2234–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achim, M.V.; Safta, I.L.; Văidean, V.L.; Mureșan, G.M.; Borlea, N.S. The Impact of COVID-19 on Financial Management: Evidence from Romania. Econ. Res. -Ekon. Istraživanja 2022, 35, 1807–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.; Depenbusch, L.; Pal, A.A.; Nair, R.M.; Ramasamy, S. Food System Disruption: Initial Livelihood and Dietary Effects of COVID-19 on Vegetable Producers in India. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, J.; Hosseini, S. Simulation-Based Assessment of Supply Chain Resilience with Consideration of Recovery Strategies in the COVID-19 Pandemic Context. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 160, 107593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Food and Agriculture Data. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy. 2018. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Shafi, M.; Liu, J.; Ren, W. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Micro, Small, and Medium-Sized Enterprises Operating in Pakistan. Res. Glob. 2020, 2, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.K.; Chowdhury, P.; Moktadir, M.A.; Lau, K.H. Supply Chain Recovery Challenges in the Wake of COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 136, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, P.C.F.; da Rocha, A. Building Resilience during the Covid-19 Pandemic: The Journey of a Small Entrepreneurial Family Firm in Brazil. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, T.; Hua, N. Transcending the COVID-19 Crisis: Business Resilience and Innovation of the Restaurant Industry in China. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beninger, S.; Francis, J.N.P. Resources for Business Resilience in a Covid-19 World: A Community-Centric Approach. Bus. Horiz. 2022, 65, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braes, B.; Brooks, D. Organisational Resilience: A Propositional Study to Understand and Identify the Essential Concepts. Ph.D. Thesis, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, B.; Salt, D. Resilience Practice: Building Capacity to Absorb Disturbance and Maintain Function; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; ISBN 1610912314. [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan, B.; Larsen, T.J.; Levine, L. Editorial Introduction to the Special Issue on: Transfer and Diffusion of IT for Organizational Resilience. J. Inf. Technol. 2007, 22, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeone, C.L. Business Resilience: Reframing Healthcare Risk Management. J. Healthc. Risk Manag. 2015, 35, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiksel, J. Sustainability and Resilience: Toward a Systems Approach. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2006, 2, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahles, H.; Susilowati, T.P. Business Resilience in Times of Growth and Crisis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 51, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangalaraj, G.; Nerur, S.; Dwivedi, R. Digital Transformation for Agility and Resilience: An Exploratory Study. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgazzar, Y.; El-Shahawy, R.; Senousy, Y. The Role of Digital Transformation in Enhancing Business Resilience with Pandemic of COVID-19. In Digital Transformation Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 323–333. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, K.S.R.; Wäger, M. Building Dynamic Capabilities for Digital Transformation: An Ongoing Process of Strategic Renewal. Long Range Plann 2019, 52, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soluk, J.; Kammerlander, N. Digital Transformation in Family-Owned Mittelstand Firms: A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 30, 676–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozanne, L.K.; Chowdhury, M.; Prayag, G.; Mollenkopf, D.A. SMEs Navigating COVID-19: The Influence of Social Capital and Dynamic Capabilities on Organizational Resilience. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 104, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ritchie, B.W.; Verreynne, M. Building Tourism Organizational Resilience to Crises and Disasters: A Dynamic Capabilities View. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 882–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, M.; Miao, S. Executive Overconfidence, Digital Transformation and Environmental Innovation: The Role of Moderated Mediator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songkajorn, Y.; Aujirapongpan, S.; Jiraphanumes, K.; Pattanasing, K. Organizational Strategic Intuition for High Performance: The Role of Knowledge-Based Dynamic Capabilities and Digital Transformation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczak, A. Robotic Process Automation as a Digital Transformation Tool for Increasing Organizational Resilience in Polish Enterprises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Long, J.; von Schaewen, A.M.E. How Does Digital Transformation Improve Organizational Resilience?—Findings from Pls-Sem and Fsqca. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, Y.A.; Giorgio, G.M.; Addeo, N.F.; Asiry, K.A.; Piccolo, G.; Nizza, A.; di Meo, C.; Alanazi, N.A.; Al-qurashi, A.D.; El-Hack, M.E.A.; et al. COVID-19 Pandemic: Impacts on Bees, Beekeeping, and Potential Role of Bee Products as Antiviral Agents and Immune Enhancers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 9592–9605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrieu, J.; Fernández-Uclés, D.; Mozas-Moral, A.; Bernal-Jurado, E. Popularity in Social Networks. The Case of Argentine Beekeeping Production Entities. Agriculture 2021, 11, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding Digital Transformation: A Review and a Research Agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magistretti, S.; Pham, C.T.A.; Dell’Era, C. Enlightening the Dynamic Capabilities of Design Thinking in Fostering Digital Transformation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 97, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellström, D.; Holtström, J.; Berg, E.; Josefsson, C. Dynamic Capabilities for Digital Transformation. J. Strategy Manag. 2022, 15, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Huang, H.; Choi, H.; Bilgihan, A. Building Organizational Resilience with Digital Transformation. J. Serv. Manag. 2023, 34, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, I.; Dutta, D.K.; Singh Ghura, A. SMEs and Digital Transformation during a Crisis: The Emergence of Resilience as a Second-Order Dynamic Capability in an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 150, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, R.M.; Nikraftar, H.; Farsi, J.Y.; Dariani, M.A. The concept of international entrepreneurial orientation in competitive firms: A review and a research agenda. Int. J. Entrep. 2019, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gholizadeh, S.; Mohammadkazemi, R. International Entrepreneurial Opportunity: A Systematic Review, Meta-Synthesis, and Future Research Agenda. J. Int. Entrep. 2022, 20, 218–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, D.J.; Varvakis, G. Dynamic Capabilities and Organizational Resilience in Turbulent Environments. In Competitive Strategies for Small and Medium Enterprises: Increasing Crisis Resilience, Agility and Innovation in Turbulent Times; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 19–37. ISBN 9783319273037. [Google Scholar]

- Wided, R. Achieving Sustainable Tourism with Dynamic Capabilities and Resilience Factors: A Post Disaster Perspective Case of the Tourism Industry in Saudi Arabia. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2060539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Rao, J.; Wan, L. The Digital Economy, Enterprise Digital Transformation, and Enterprise Innovation. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2022, 43, 2875–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Zomer, T.T.; Neely, A.; Martinez, V. Digital Transforming Capability and Performance: A Microfoundational Perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 1095–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.; Gouveia Rodrigues, R.; Ferreira, J.J. Small Agricultural Businesses’ Performance—What Is the Role of Dynamic Capabilities, Entrepreneurial Orientation, and Environmental Sustainability Commitment? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 1898–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.; Sidorova, A.; Jones, M.C. Enabling Firm Performance through Business Intelligence and Analytics: A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 822–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Pateli, A. Information Technology-Enabled Dynamic Capabilities and Their Indirect Effect on Competitive Performance: Findings from PLS-SEM and FsQCA. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Raza, S.; Nurunnabi, M.; Minai, M.S.; Bano, S. The Impact of Entrepreneurial Business Networks on Firms’ Performance Through a Mediating Role of Dynamic Capabilities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, O.; Daddi, T.; Iraldo, F. Sensing, Seizing, and Reconfiguring: Key Capabilities and Organizational Routines for Circular Economy Implementation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Malik, M. How Do Dynamic Capabilities Enable Hotels to Be Agile and Resilient? A Mediation and Moderation Analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 106, 103266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Martín, M.Á.; Castaño-Martínez, M.S.; Méndez-Picazo, M.T. Digital Transformation, Digital Dividends and Entrepreneurship: A Quantitative Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sharma, M.; Dhir, S. Modeling the Effects of Digital Transformation in Indian Manufacturing Industry. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assar, S.; Rupeika-Apoga, R.; Petrovska, K.; Bule, L. The Effect of Digital Orientation and Digital Capability on Digital Transformation of SMEs during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaziz, F.; Smaoui Hachicha, Z. Strategic Human Resource Management Practices and Organizational Resilience. J. Manag. Dev. 2018, 37, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, D.; Joshi, G. Impact of Psychological Capital and Life Satisfaction on Organizational Resilience during COVID-19: Indian Tourism Insights. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 2398–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.S.; Rai, S.; Singh, N.K. Organizational Resilience and Social-Economic Sustainability: COVID-19 Perspective. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 12006–12023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM): An Emerging Tool in Business Research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M.; Baron, P.; Balev, J. The Beck Depression Inventory: A Cross-Validated Test of Second-Order Factorial Structure for Bulgarian Adolescents. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1998, 58, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syamsulbahri, D. Analisis Keberhasilan Dan Kegagalan Pelaksanaan Program Iptekda LIPI. Pemberdayaan UKM Melalui Program Iptekda LIPI 2006. Available online: http://lipi.go.id/berita/single/Iptekda-LIPI-Agar-Dijadikan-Model/7184 (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Villalonga, B.; Amit, R. How Do Family Ownership, Control and Management Affect Firm Value? J. Financ. Econ. 2006, 80, 385–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, M. Corporate Governance and Competitive Advantage in Family–Controlled Firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Newsted, P.R. Structural Equation Modeling Analysis with Small Samples Using Partial Least Squares. Stat. Strateg. Small Sample Res. 1999, 1, 307–341. [Google Scholar]

- Atmadja, A.S.; Su, J.J.; Sharma, P. Examining the Impact of Microfinance on Microenterprise Performance (Implications for Women-Owned Microenterprises in Indonesia). Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2016, 43, 962–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Pieper, T.M.; Ringle, C.M. The Use of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in Strategic Management Research: A Review of Past Practices and Recommendations for Future Applications. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 320–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 1462523358. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS Path Modeling in New Technology Research: Updated Guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fueki, K.; Yoshida, E.; Igarashi, Y. A Structural Equation Model to Investigate the Impact of Missing Occlusal Units on Objective Masticatory Function in Patients with Shortened Dental Arches. J. Oral Rehabil. 2011, 38, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vathanophas, V.; Krittayaphongphun, N.; Klomsiri, C. Technology Acceptance toward E-Government Initiative in Royal Thai Navy. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2008, 2, 256–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearne, M.; Srinivasan, N.; Weinstein, L. Effect of Technology on Sales Performance: Progressing from Technology Acceptance to Technology Usage and Consequence. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2004, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Suárez, K.; de Saá-Pérez, P.; García-Almeida, D. The Succession Process from a Resource-and Knowledge-based View of the Family Firm. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2001, 14, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D Macredie, R.; Mijinyawa, K. A Theory-Grounded Framework of Open Source Software Adoption in SMEs. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2011, 20, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, Z.; Nieto, M.J. Internationalization Strategy of Small and Medium-Sized Family Businesses: Some Influential Factors. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2005, 18, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarazzo, M.; Penco, L.; Profumo, G.; Quaglia, R. Digital Transformation and Customer Value Creation in Made in Italy SMEs: A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, O.; Daddi, T.; Iraldo, F. Microfoundations of Dynamic Capabilities: Insights from Circular Economy Business Cases. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1479–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellermanns, F.W.; Eddleston, K.A.; Sarathy, R.; Murphy, F. Innovativeness in Family Firms: A Family Influence Perspective. Small Bus. Econ. 2012, 38, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. An Overview of the Field of Family Business Studies: Current Status and Directions for the Future. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2004, 17, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; le Breton-Miller, I.; Scholnick, B. Stewardship vs. Stagnation: An Empirical Comparison of Small Family and Non-family Businesses. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, B.; Jaussaud, J. Family and Non-Family Business Resilience in an Economic Downturn. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2012, 18, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosse, S.; Grubbström, A. Continuity in Farming-Not Just Family Business. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 50, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Eggers, F.; Kraus, S.; Cheng, C.-F.; Chang, M.-L. Marketing-Related Resources and Radical Innovativeness in Family and Non-Family Firms: A Configurational Approach. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5620–5627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Xie, Y.; Hu, S.; Song, J. Exploring How Entrepreneurial Orientation Improve Firm Resilience in Digital Era: Findings from Sequential Mediation and FsQCA. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewton, K.E.; Danes, S.M.; Stafford, K.; Haynes, G.W. Determinants of Rural and Urban Family Firm Resilience. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2010, 1, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, F.; Nordqvist, M. Dynamic Capabilities and Trans-Generational Value Creation in Family Firms: The Role of Organizational Culture. Int. Small Bus. J. 2010, 28, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, P.; Kammerlander, N.; van Essen, M.; Zellweger, T. Doing More with Less: Innovation Input and Output in Family Firms. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1224–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Hayton, J.C.; Salvato, C. Entrepreneurship in Family vs. Non–Family Firms: A Resource–Based Analysis of the Effect of Organizational Culture. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2004, 28, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Doll, W.J.; Cao, M. Exploring the Absorptive Capacity to Innovation/Productivity Link for Individual Engineers Engaged in IT Enabled Work. Inf. Manag. 2008, 45, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimpe, C.; Sofka, W. Search Patterns and Absorptive Capacity: Low-and High-Technology Sectors in European Countries. Res. Policy 2009, 38, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, J.J.; Hanelt, A.; Kolbe, L.M. Understanding the Influence of Absorptive Capacity and Ambidexterity on the Process of Business Model Change–the Case of On-premise and Cloud-computing Software. Inf. Syst. J. 2016, 26, 477–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, R.K.Z.; Mishra, C.S. Family Entrepreneurship. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2008, 46, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, G.G.; da Silva Braga, V.L.; da Encarnação Marques, C.S.; Ratten, V. Corporate Entrepreneurship Education’s Impact on Family Business Sustainability: A Case Study in Brazil. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Huang, W.-C.; Toiba, H.; Efani, A. Does adaptation to climate change promote household food security? Insights from Indonesian fishermen. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2022, 29, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dynamic Capability (X) [26,45,46,47,48,49,50] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sensing | 1 | I can identify new, more profitable technologies |

| 2 | I have regular customers | |

| 3 | I can understand market conditions | |

| 4 | I always try to identify obstacles that make business processes inefficient | |

| 5 | I can identify new opportunities in the beekeeping business that competitors have not discovered | |

| 6 | I continue to develop beekeeping products to suit consumer needs | |

| 7 | I constantly look for ideas to improve the honey product quality | |

| 8 | I have to be proactive and reactive to business changes during the pandemic to anticipate challenges that threaten the sustainability | |

| Seizing | 9 | I am willing to learn about new technology |

| 10 | I continue to improve business strategies to take advantage of the current situation | |

| 11 | I am willing to spend money to solve pandemic-induced problems in the beekeeping business | |

| 12 | I maintained the best beekeeping business model during the pandemic | |

| 13 | I continue to increase my knowledge to develop beekeeping products | |

| 14 | I use knowledge to create new products | |

| 15 | I can formulate a business strategy | |

| 16 | I can secure strategic partnerships | |

| 17 | I can plan future investments in the beekeeping business | |

| 18 | I can analyze business feasibility (IRR/NPV, ROI, ROA, ROE) | |

| 19 | I can identify human resource requirements for the business | |

| Reconfiguring | 20 | I can control and access beekeeping products’ prices |

| 21 | I can create new beekeeping products that are different from competitors | |

| 22 | I can respond and adapt to unexpected business changes | |

| 23 | I can invite business partners with high potential to work together, and I terminate partnerships with lower potential | |

| 24 | I can adapt the business processes to respond to changing business priorities | |

| 25 | I can change business processes to generate better profits | |

| 26 | I try to create effective and efficient communication in the beekeeping business | |

| 27 | I can grow employees’ sense of responsibility to succeed in changing business plans for the better | |

| 28 | I can maintain consistency amid the changes in the beekeeping business caused by the pandemic | |

| 29 | I implement changes in the business plan to be flexible and adaptive to changes in the current business conditions | |

| Digital Transformation (Y) [51,52,53] | ||

| IT Readiness | 1 | I use online platforms to store data related to the beekeeping business, such as Google Drive and Dropbox |

| 2 | I use emails to support the beekeeping business | |

| 3 | I use software such as Microsoft Word, Excel, and PowerPoint to run a honey business | |

| 4 | I use social media (such as WA, Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, Twitter, and YouTube) to support my honey business | |

| 5 | I use the website to support the honey business | |

| 6 | I use the Google Analytics/Search Engine Optimization/Google Business/Social Media Analytics application to analyze honey sales | |

| 7 | I can integrate digital technology (WhatsApp, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, data storage platforms (Google Drive), and data analytical tools (Google Analytics and social media analytics) in running a beekeeping business | |

| Strategic Alignment | 8 | The role of digital technology, such as social media, storage platforms, and analytical tools, can change my business model |

| 9 | I feel that social media helps me connect directly with consumers and suppliers and better analyze the consumer journey | |

| 10 | I feel that digital technology can maintain beekeeping business market shares in the future and can even create new jobs | |

| 11 | I feel that digital technology helps strengthen the beekeeping business’ internal capabilities | |

| 12 | I feel that digital technology helps increase the amount of annual income of the beekeeping business | |

| Business Resilience (Z) [26,54,55,56] | ||

| Organizational Robustness | 1 | I can take quick actions to deal with business changes |

| 2 | I am prepared to manage business challenges that we can foresee | |

| 3 | I can develop new business alternatives to take advantage of the pandemic situation | |

| 4 | I can meet customer needs without disruption | |

| 5 | I continued to maintain the supply network during the pandemic | |

| 6 | I prepared myself when the news of the pandemic broke | |

| 7 | I act in totality in dealing with undesirable business situations | |

| Readiness | 8 | I realize and understand that the pandemic has an impact on the beekeeping business |

| 9 | I took precautions because honey products did not sell well | |

| 10 | I plan and prepare strategies for dealing with future business disruptions | |

| Response | 11 | I recognized the business threats posed by the COVID-19 pandemic |

| 12 | I could quickly respond to the negative impact of the pandemic honey sales | |

| 13 | I could provide a solution and recover the beekeeping business from the decreasing consumer awareness after the pandemic | |

| 14 | I have honey products that are considered essential for consumption not only during but also after the COVID-19 pandemic | |

| 15 | I built partnerships with partners during the pandemic and will continue to survive after the pandemic | |

| 16 | I have sufficient internal resources (financial, human resources, production) to deal with unexpected business changes, such as a pandemic | |

| 17 | I can respond appropriately to unexpected disruptions such as pandemics | |

| 18 | I prepare myself as a business manager to deal with a future crisis | |

| Recovery | 19 | I have good internal and external communication, such as with partners and consumers |

| 20 | I managed to deal with the crisis caused by the pandemic | |

| 21 | I responded quickly to threats that arose during a pandemic | |

| Description | Micro-FB (78) | Small-FB (217) | Small-NFB (37) | Medium-FB (56) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | |

| Age | ||||||||

| 21–30 | 23.0 | 29.5 | 31 | 14.3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7.1 |

| 31–40 | 16.0 | 20.5 | 54 | 24.9 | 9 | 24.3 | 14 | 25.0 |

| 41–50 | 31.0 | 39.7 | 94 | 43.3 | 13 | 35.1 | 22 | 39.3 |

| 51–60 | 8.0 | 10.3 | 35 | 16.1 | 13 | 35.1 | 14 | 25.0 |

| 60 above | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1.4 | 2 | 5.4 | 2 | 3.6 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 71.0 | 91 | 210 | 96.8 | 37 | 100.0 | 55 | 98.2 |

| Female | 7.0 | 9 | 7 | 3.2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Occupation | ||||||||

| First job | 72.0 | 92.3 | 204 | 94.0 | 37 | 100.0 | 53 | 94.6 |

| Side job | 6.0 | 7.7 | 13 | 6.0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5.4 |

| Capital | ||||||||

| Self Capital | 7.0 | 9 | 49 | 22.6 | 11 | 29.7 | 14 | 25.0 |

| Formal | 25.0 | 32 | 68 | 31.3 | 16 | 43.2 | 16 | 28.6 |

| Informal | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2.3 | 8 | 21.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Self and formal | 46.0 | 59,0 | 95 | 43.8 | 1 | 2.7 | 26 | 46.4 |

| Self and informal | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Formal and informal | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.7 | 0 | 0 |

| Income | ||||||||

| <10 juta | 31.0 | 39.7 | 70 | 32.3 | 8 | 21.6 | 5 | 8.9 |

| 10–20 juta | 39.0 | 50.0 | 89 | 41.0 | 21 | 56.8 | 13 | 23.2 |

| 20 juta above | 8.0 | 10.3 | 58 | 26.7 | 8 | 21.6 | 38 | 67.9 |

| Education | ||||||||

| No education | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6.6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Primary education | 19.0 | 24.4 | 76 | 35.0 | 3 | 8.1 | 13 | 23.2 |

| Junior education | 22.0 | 28.2 | 78 | 35.9 | 5 | 13.5 | 17 | 30.4 |

| Senior education | 35.0 | 44.9 | 51 | 23.5 | 29 | 78.4 | 22 | 39.3 |

| Graduate | 2.0 | 2.6 | 6 | 2.8 | 1 | 2.7 | 3 | 5.4 |

| Postgraduate | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Firm Age | ||||||||

| <10 years | 15 | 19.2 | 17 | 7.8 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7.1 |

| 10 years above | 63 | 80.8 | 200 | 92.2 | 37 | 100.0 | 52 | 92.9 |

| Number of Family | ||||||||

| <5 | 63 | 80.8 | 162 | 74.7 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 71.4 |

| >5 | 15 | 19.2 | 55 | 25.3 | 37 | 100.0 | 16 | 28.6 |

| Product demand during crisis | ||||||||

| Stable | 6 | 8.0 | 15 | 6.9 | 8 | 21.6 | 3 | 5.4 |

| Decrease | 2 | 3.0 | 8 | 3.7 | 7 | 18.9 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Increase | 70 | 89.0 | 194 | 89.4 | 22 | 59.5 | 52 | 92.9 |

| Business Risk Factor | ||||||||

| Internal | 7 | 9.0 | 19 | 8.8 | 14 | 37.8 | 14 | 25.0 |

| Eksternal | 68 | 87.2 | 159 | 73.3 | 23 | 62.2 | 33 | 58.9 |

| Internal and External | 3 | 3.8 | 39 | 18.0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 16.1 |

| Business Motivation | ||||||||

| Investation | 25 | 32.1 | 57 | 26.3 | 4 | 10.8 | 16 | 28.6 |

| Business oriented | 36 | 46.2 | 26 | 12.0 | 33 | 89.2 | 28 | 50.0 |

| Both | 17 | 21,8 | 134 | 61,80 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 21.4 |

| Honey Product Variance | ||||||||

| Pure honey | 77 | 98.7 | 170 | 78.3 | 32 | 86.5 | 31 | 55.4 |

| Honey product processing | 0 | 0 | 9 | 4.1 | 5 | 13.5 | 10 | 17.9 |

| Both | 1 | 1.3 | 38 | 17.5 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 26.8 |

| Social Media Used | ||||||||

| Facebook, instagram | 65 | 83.3 | 207 | 95.4 | 37 | 100.0 | 55 | 98.2 |

| Facebook, isntagram, TikTok | 13 | 16.7 | 10 | 4.6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Youtoube | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Payment Method | ||||||||

| Cash | 16 | 20.5 | 64 | 29.5 | 2 | 5.4 | 17 | 30.4 |

| Cashless (mobile banking, e-money) | 18 | 23.1 | 116 | 53.5 | 33 | 89.2 | 21 | 37.5 |

| Both | 44 | 56.4 | 37 | 17.1 | 2 | 5.4 | 18 | 32.1 |

| Offline Store | ||||||||

| Yes, available | 62 | 79.5 | 153 | 70.5 | 1 | 2.7 | 21 | 37.5 |

| No | 16 | 20.5 | 64 | 29.5 s | 36 | 97.3 | 35 | 62.5 |

| Construct. | Second Order | Item | Loading | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (micro-FB) | ||||||

| DC | 0.758 | 0.857 | 0.667 | |||

| Sensing | X1 | 0.759 | ||||

| Seizing | X2 | 0.874 | ||||

| Reconfiguring | X3 | 0.813 | ||||

| DT | 0.550 | 0.813 | 0.686 | |||

| IT-Readiness | Y1 | 0.877 | ||||

| Strategic Alignment | Y2 | 0.777 | ||||

| Model 2 (small-FB) | ||||||

| DT | 0.837 | 0.901 | 0.753 | |||

| Sensing | X1 | 0.828 | ||||

| Seizing | X2 | 0.867 | ||||

| Reconfiguring | X3 | 0.906 | ||||

| DT | 0.674 | 0.857 | 0.751 | |||

| IT-Readiness | Y1 | 0.906 | ||||

| Strategic Alignment | Y2 | 0.824 | ||||

| Model 3 (small-NFB) | ||||||

| DC | 0.602 | 0.788 | 0.564 | |||

| Sensing | X1 | 0.555 | ||||

| Seizing | X2 | 0.731 | ||||

| Reconfiguring | X3 | 0.921 | ||||

| DT | 0.904 | 0.954 | 0.912 | |||

| IT-Readiness | Y1 | 0.951 | ||||

| Strategic Alignment | Y2 | 0.959 | ||||

| Model 4 (Medium-FB) | ||||||

| DC | 0.843 | 0.903 | 0.758 | |||

| Sensing | X1 | 0.871 | ||||

| Seizing | X2 | 0.924 | ||||

| Reconfiguring | X3 | 0.813 | ||||

| DT | 0.644 | 0.848 | 0.737 | |||

| IT-Readiness | Y1 | 0.878 | ||||

| Strategic Alignment | Y2 | 0.839 | ||||

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Std.Beta | O/STDEV | p-Values | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (Micro-Family Business) | ||||||

| Direct effect | ||||||

| H1 | DC > > > DT | 0.655 | 11.692 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| H2 | DT > > > RES | 0.024 | 0.110 | 0.912 | Rejected | |

| H3 | DC > > > RES | 0.522 | 2.442 | 0.015 | Supported | |

| Indirect effect | ||||||

| H4 | DC > DT > RES | 0.016 | 0.111 | 0.912 | Rejected | |

| Model 2 (Small-Family business) | ||||||

| Direct effect | ||||||

| H1 | DC > > > DT | 0.773 | 34.512 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| H2 | DT > > > RES | 0.627 | 7.865 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| H3 | DC > > > RES | 0.245 | 3.289 | 0.001 | Supported | |

| Indirect effect | ||||||

| H4 | DC > DT > RES | 0.189 | 3.270 | 0.001 | Supported | |

| Model 3 (Small-Non Family Business) | ||||||

| Direct effect | ||||||

| H1 | DC > > > DT | 0.802 | 2.603 | 0.010 | Supported | |

| H2 | DT > > > RES | 0.033 | 0.114 | 0.909 | Rejected | |

| H3 | DC > > > RES | 0.816 | 1.231 | 0.219 | Rejected | |

| Indirect effect | ||||||

| H4 | DC > DT > RES | 0.654 | 1.476 | 0.141 | Rejected | |

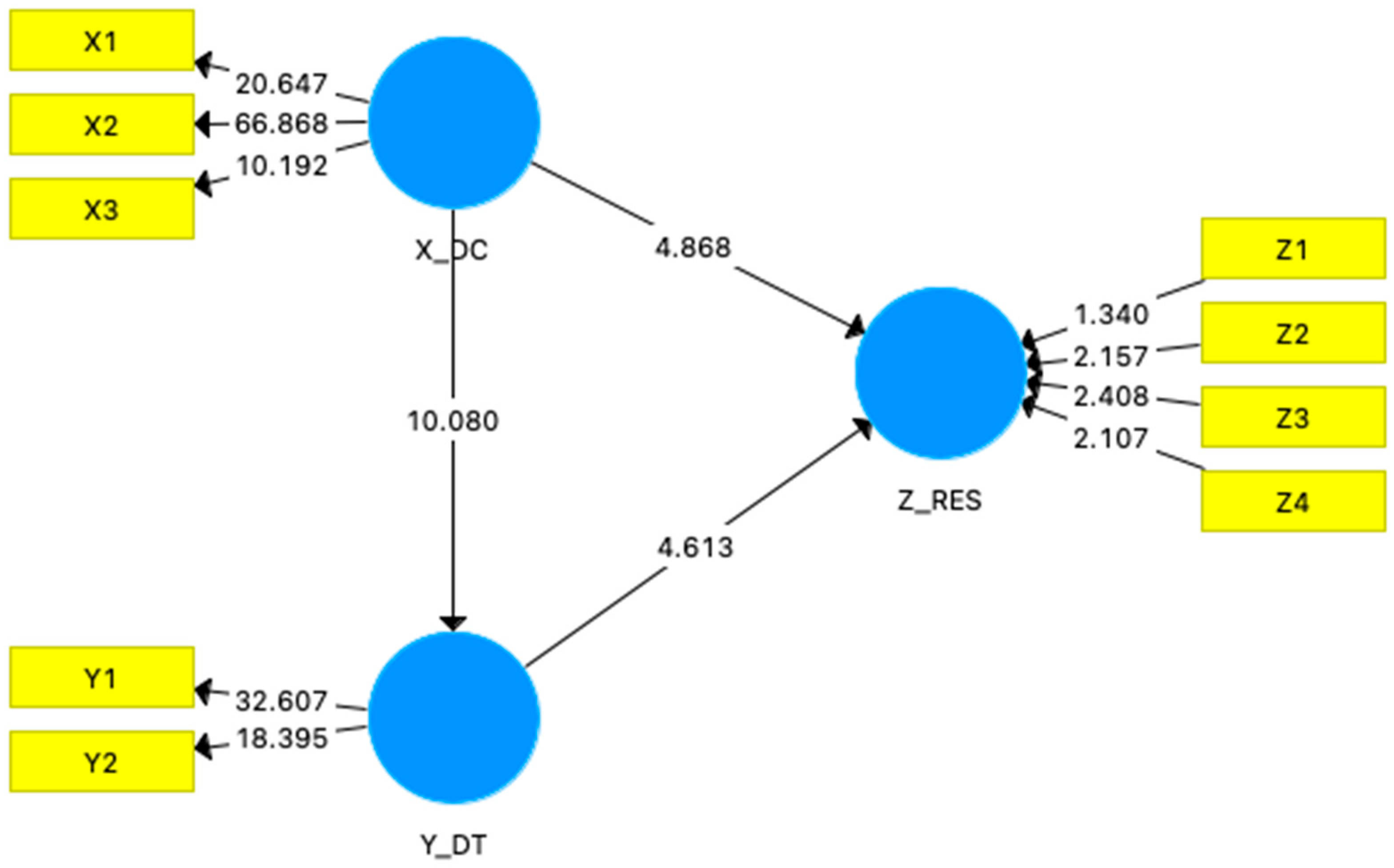

| Model 4 (Medium-Family Business) | ||||||

| Direct effect | ||||||

| H1 | DC > > > DT | 0.601 | 10.080 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| H2 | DT > > > RES | 0.455 | 4.613 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| H3 | DC > > > RES | 0.482 | 4.868 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| Indirect effect | ||||||

| H4 | DC > DT > RES | 0.274 | 3.895 | 0.000 | Supported | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Putritamara, J.A.; Hartono, B.; Toiba, H.; Utami, H.N.; Rahman, M.S.; Masyithoh, D. Do Dynamic Capabilities and Digital Transformation Improve Business Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Insights from Beekeeping MSMEs in Indonesia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031760

Putritamara JA, Hartono B, Toiba H, Utami HN, Rahman MS, Masyithoh D. Do Dynamic Capabilities and Digital Transformation Improve Business Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Insights from Beekeeping MSMEs in Indonesia. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):1760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031760

Chicago/Turabian StylePutritamara, Jaisy Aghniarahim, Budi Hartono, Hery Toiba, Hamidah Nayati Utami, Moh Shadiqur Rahman, and Dewi Masyithoh. 2023. "Do Dynamic Capabilities and Digital Transformation Improve Business Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Insights from Beekeeping MSMEs in Indonesia" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 1760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031760

APA StylePutritamara, J. A., Hartono, B., Toiba, H., Utami, H. N., Rahman, M. S., & Masyithoh, D. (2023). Do Dynamic Capabilities and Digital Transformation Improve Business Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Insights from Beekeeping MSMEs in Indonesia. Sustainability, 15(3), 1760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031760