Abstract

Despite growing scholarly attention to what determines effective corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication, consumers’ limited awareness of and attention to CSR messages remain critical challenges for organizations. This study aims to examine the effects of message specificity on an organization’s intended outcomes of CSR communication and to explore the mediating role of perceived social distance in these relationships by applying construal level theory (CLT). We conducted an online experiment (n = 293), and the results revealed that message specificity had a positive impact on consumer-company identification, word-of-mouth intention, and CSR participation intention. Moreover, perceived social distance significantly mediated the relationships between message specificity and the outcomes of CSR communication. Applying CLT, this study offers theoretical implications for the psychological mechanism of how message specificity generates desired outcomes in CSR communication. In addition, we tested these mediation effects in the context of the geographic proximity (close vs. remote) of the CSR communication to participants; the practical implication is that reducing perceived social distance through message specificity is even more effective for geographically distant CSR campaigns.

1. Introduction

Consensus on the definition of corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities is lacking, but they typically focus on corporations’ commitment to avoiding harm and enhancing society’s well-being [1,2,3]. In recent years, consumers’ expectations of companies’ role in society and behavior as responsible businesses have increased, and in today’s globalized society, CSR activities often extend beyond the boundaries of one country. The benefits of CSR activities, both to companies and society, have been well documented in the literature [4,5,6,7].

The crucial condition for maximizing these benefits is consumers’ awareness of and engagement with CSR activities. CSR communication scholars have endeavored to develop effective communication strategies to increase awareness of [8], reduce skepticism about [9], and generate favorable attitudes toward companies [10], as well as increase consumer engagement with CSR activities [11]. A fundamental challenge to CSR communication, however, is consumers’ lack of attention to CSR messages, unless a CSR activity has led to controversy [12,13], and this is likely to be even more true of CSR activities occurring overseas. Although studies have explored strategies to make CSR activities more relatable to consumers [14,15,16], these have largely been restricted to activities carried out within a single nation.

In the present study, we aim to fill this gap by focusing on message specificity as a strategy to overcome the challenges of CSR communication. The purpose of this study, therefore, is to investigate the role of message specificity in generating the intended outcomes of CSR activities and explore the mediating role of perceived psychological distance as grounded in construal level theory (CLT). We also tested these relationships on two different levels of geographic proximity—close vs. remote—to examine whether there is an optimal context for leveraging the message strategy. Ultimately, our results have both theoretical and practical implications.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2, the literature review, describes (1) the concept of message specificity and its relevance to CSR communication; (2) the role of perceived social distance as a mediator between the effect of message specificity and the three outcomes of CSR communication (consumer-company identification (CCI), word-of-mouth (WOM) intention, and CSR participation intention); and (3) the geographic proximity of a CSR campaign location as a contextual factor. Based on our conceptual framework, we developed research hypotheses and a research question. Section 3 discusses our experimental design and procedure, along with information about participants, stimuli, measures, and manipulation checks. Section 4 summarizes the research results. Section 5 discusses the study results and practical implications, as well as its limitations and suggestions for future research. Finally, Section 6 presents conclusions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Message Specificity in CSR Communication

Given the importance of CSR communication, researchers have analyzed various aspects and functions of CSR communication. Among them, the message content factor is fundamental, as it drives awareness and consumer reactions, which determines the success of a CSR campaign [17]. Increased stakeholder awareness can be achieved through corporate efforts to share detailed information about CSR activities, such as specific commitments, social impact, and motives for CSR engagement [8]. Previous research has demonstrated the effects of message specificity on various outcomes, such as message evaluations [9,18,19,20], consumer perceptions of companies [17,21], and behavioral intentions [11,22].

Although message specificity has no single definition, it typically involves the extent to which an object or piece of information is described in terms of “specific-ness” or the degree of uniqueness of a particular subject or piece of information [9]. In the context of CSR, Pérez et al. [20] defined message specificity as the introduction of concrete facts that demonstrate how much the company contributes to CSR, as well as the extent to which “CSR activities make a real and meaningful difference to society and corporate stakeholders” (p. 34).

Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of message specificity on various outcomes. At the cognitive level, Petty and Cacioppo [23] demonstrated that product messages with concrete arguments generated more favorable responses regarding perceived product attributes than did messages with general arguments. Similarly, Benoit [24] found argument specificity to be related to favorable cognitions about product brand and attitude change. Roberson et al. [25] demonstrated that message specificity led to improved perceptions of organization qualities and person–organization fit. Baghi et al. [21] showed that vivid statements—defined as being elaborated, mentally stimulating, and emotionally engaging—as opposed to pallid ones, elicited more favorable affective responses and higher consumer trust in a company’s efficient use of resources. These insights demonstrate how comprehensive CSR information may help influence how customers react to CSR initiatives.

Furthermore, Pérez et al. [20] found that providing customers with concrete information about the results of the CSR activities increased their perceptions of the attractiveness and legitimacy of the CSR message. Message specificity mattered even when there was a good fit between a company and its CSR initiatives, according to Lim and Lee [9]. They showed that specific messages improved cognitive fluency and reduced suspicion about a company’s CSR more than less specific ones. Similarly, Ganz and Grimes [19] demonstrated the influence of message specificity on the perceived credibility of green claims in advertisements.

Other studies have suggested that the impact of message specificity extends to behavioral outcomes. According to Grau et al. [11], detailed information about cause-related marketing (CRM) initiatives, such as the sums donated, the length of the campaign, and the maximum contributions, can boost consumer confidence. Xiao et al. [22] also found that a message that included specific fundraising results prompted a stronger intention to donate through heightened message credibility and perceptions of transparency. One possible reason for the positive impact of specific information is that it can help consumers simplify processing mechanisms by considering concrete language as a heuristic cue that increases perceived authenticity [20]. Therefore, when crafting CSR messages, companies need to provide an authentic and compelling story that incorporates various facts while meeting consumer expectations [8,26]. Thus, message specificity can be considered an effective way to communicate corporate actions based on the use of concrete language, which enables consumers to recognize the realistic aspects of CSR efforts and find the information conveyed to be believable [26].

In the present study, we focus on three outcomes of CSR communication—consumer-company identification (CCI), word-of-mouth (WOM) intention, and CSR participation intention—as they have not been explored in relation to message specificity. We assume that message specificity as an accessible heuristic cue can simplify consumers’ processing, thus bypassing further cognitive efforts to develop skepticism and resulting in favorable evaluations at the cognitive (i.e., CCI) and behavioral levels (i.e., WOM and CSR participation intention).

First, CCI has been identified as a moderator that determines the consequences of CSR communication [27]. CCI indicates a strong, committed, and meaningful consumer-company relationship that refers to consumers’ identification with companies that help them satisfy their self-definitional needs [28]. Kim [27] found that consumers with high CCI were more likely to exhibit positive outcomes of CSR communication, such as consumer CSR knowledge, trust, and perception of corporate reputation, than were those with low CCI—even a promotional tone in CSR messages was more acceptable to consumers with high CCI than to those with low CCI. Although CCI has been examined as a moderating factor in the context of CSR communication, the present study examines the impact of message specificity on CCI. Specifically, message specificity is expected to have a positive influence on CCI, demonstrating the link between consumers’ message processing of specific information and their identification with the company. Therefore, we posit the following hypothesis:

H1a.

A specific message leads to greater consumer-company identification (CCI) than does an abstract message.

The positive corporate image created by CSR endeavors can contribute to consumers’ favorable perceptions of the company through the halo effect, which can help increase consumer attention to and interest in corporate products and services [29]. Once consumers appreciate the corporations’ active CSR involvement, they tend to build favorable attitudes toward and speak positively about the company, which results in spreading positive WOM for the company [29]. Positive WOM refers to favorable communications about a particular company that a consumer is willing to share with others [30], which helps the company obtain new customers [31,32]. In particular, Dalla-Pria and Rodríguez-de-Dios [33] demonstrated how message-related aspects are the foundation for WOM’s operation: CSR messages that were framed in terms of values-driven (as opposed to performance-driven) motives and that had a corporate source as opposed to an influencer source generated increased WOM intention.

CSR messages that were based on a corporate source (vs. an influencer source) and framed in terms of values-driven (vs. performance-driven) motives gained more WOM intention. Thus, discovering how to identify predictors of positive WOM intention should be an important consideration when developing CSR messages. In line with our literature review, we hypothesize that increased WOM intention occurs when a CSR message is more specific than abstract, as follows:

H1b.

A specific message leads to greater word-of-mouth (WOM) intention than does an abstract message.

Previous studies investigating the outcomes of CSR activities have consistently confirmed that consumers are inclined to exhibit favorable behavioral intentions, such as speaking positively about companies that are actively engaged in CSR initiatives [4]. Once a cause is presented with a localized, tangible impact, even less involved consumers tend to show interest in the cause, indicating a potential connection to their willingness to participate [11]. Conversely, the literature emphasizes the negative impact of consumer skepticism on achieving desired CSR outcomes [34,35,36], and this skepticism extends to CSR messages. Consequently, consumer skepticism toward CSR communications can significantly influence behavioral intentions, including CSR participation intentions. However, using concrete messages can help consumers envision a company’s CSR efforts and, in turn, recognize the genuine value of these endeavors in the real world and perceive the CSR information as reliable and trustworthy [26].

In light of the previous findings, we posit that message specificity can lead to consumer participation intentions in response to CSR communication:

H1c.

A specific message leads to greater CSR participation intention than does an abstract message.

2.2. The Role of Perceived Social Distance as a Mediator

The fundamental process by which CSR messages affect consumers based on their individual psychological perceptions of CSR activities, however, is still unknown. Research has indicated that the success of CSR communication is influenced by public perceptions, such as perceptions of a company’s CSR efforts and CSR skepticism [17,20,34] as well as people’s involvement in causes [11,37,38]. We attempt to fill this gap in the CSR communication literature by delving into the fundamental mechanisms that underlie the influence of message specificity on cognitive and behavioral outcomes. Specifically, we employed CLT, which elucidates the cognitive processes that mediate the translation of abstract and concrete information into mental representations. By leveraging CLT, we aim to provide a nuanced understanding of how message specificity shapes people’s perceptions and behavioral intentions.

According to CLT, individuals form mental construals, and these are influenced by the psychological distance they perceive between themselves and various objects, events, and behaviors. These mental construals serve to facilitate the comprehension, evaluation, and prediction of these items, events, and behaviors [39]. To compensate for the limitations of firsthand experiences in the current moment, individuals must transcend their immediate circumstances and take into account different dimensions of psychological distance [40]. CLT posits that there is a positive relationship between psychological distance and the level at which people mentally construe objects. In other words, the reference point for psychological distance, according to CLT, is “the self” in the “here and now” [39]. Psychological distance is said to influence how an event is mentally construed [39,41,42]. Depending on their subjective assessments of the psychological distance between themselves and the event, people interpret the same experience in a variety of ways, ranging from low-to-high construals [42,43]. The more distant an event is from a person, the more abstract their thinking will be regarding it, whereas the closer the event is, the more concrete their thinking will be about it [39]. This psychological distance consists of four dimensions: spatial, social, temporal, and hypothetical [40,44].

Liberman et al. [44] define social distance as the perceived differences between one person or group and another. According to Linville et al. [45], social proximity or distance of another person or circumstance, such as an in-group versus an out-group member, is typically used to measure social distance. When the social distance from another individual increases—for example, from an in-group member (close social distance) to an out-group member (distant social distance)—people become more likely to construe the target person using abstract terms [41]. This is because people construe socially distant objects and situations using abstract representations (high-level construal), whereas they construe socially close events in more action-oriented and concrete terms (low-level construal) [39,42,46].

In other words, social distance has an impact on people’s subjective views, making similar people—like members of their own group—appear closer to them than different people—like members of other groups [39]. For instance, individuals tend to interpret the target event of a CSR campaign in abstract terms when the social distance from it grows, making them perceive it as different and making them feel as though it were an unrelatable target (far social distance). In contrast, people tend to think more concretely about a CSR campaign when their social distance from it is reduced and they begin to see it as comparable to themselves or as an extension of their social group (near social distance). Given consumers’ low degree of understanding of CSR, making CSR messages that affect other people, such as the participants and beneficiaries of a CSR campaign, accessible to people who do not directly benefit becomes crucial. We anticipate that assessing perceived social distance as a mediator can enhance the effectiveness of the message in generating favorable CSR outcomes.

In one study, when consumers were exposed to detailed information versus abstract information in an approachable luxury brand’s CSR ad, they perceived the detailed ad as being more congruent with the brand compared to the abstract ad [47]. For an aspiration-based (less-approachable) luxury brand, however, the difference in ad–brand congruency effects disappeared because this brand was construed on a high-level. This study applies this link to the setting of CSR communication.

Previous research has demonstrated how social distance can function as a relevant factor in understanding consumer perceptions of CSR efforts, such as consumer–CSR activity closeness or consumer-company closeness [42,48,49]. For instance, Lii et al. [48] found that the relationship between CSR initiatives and consumer evaluations was stronger when consumers perceived both the brand and the cause as socially closer to themselves and that positive consumer evaluations were generated when consumers believed companies’ values to be similar to their own (CCI), signaling the important role of closer social distance in perceiving CSR initiatives. In a similar vein, Sung et al. [50] explained that shortening social distance can positively influence brand equity when developing CSR messages on social media. In the advertising and marketing domains, consumer–brand social distance has been found to affect consumer responses and brand evaluations [51,52,53]. Recent research has provided an explanation for the link between CSR messages and social distance [54]. CSR messages designed to decrease social distance increased individuals’ cause involvement and, subsequently, their positive WOM intention and brand attitudes.

In contrast to previous studies using perceived social distance from a target organization itself, such as consumer-company/brand social distance [55], the present study examines, from a consumer perspective, how perceived social distance from a CSR campaign mediates the impact of message specificity on the results of CSR communication. To perform this, we evaluated how consumers assessed CSR campaigns by considering the conceptual combinations of message specificity, framed as either specific or abstract, paired with either low-level or high-level construal and perceived social distance to the target CSR campaign, defined as either close or distant.

Moreover, the present study seeks to fill the gap in the literature on CSR communication in the context of message specificity and the role of perceived social distance, assuming that consumers do not simply accept CSR messages but instead interpret them according to their perceived social distance. Although previous research has demonstrated the role of social distance as a mediator in influencing brand equity [50], the literature has not sufficiently demonstrated the impact of different types of CSR message specificity on the outcomes of CSR communication along with a mediating factor, such as perceived social distance to CSR campaigns. Accordingly, we focus on the mediating role of perceived social distance in the interplay between message specificity and consumer perceptions and behavioral intentions as outcomes of CSR communication. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2a.

Perceived social distance mediates the effect of message specificity on consumer-company identification (CCI).

H2b.

Perceived social distance mediates the effect of message specificity on word-of-mouth (WOM) intention.

H2c.

Perceived social distance mediates the effect of message specificity on CSR participation intention.

2.3. Geographic Proximity: Location of a CSR Campaign

Businesses increasingly demand CSR actions on a global scale as they expand their operations across borders, and corporate managers are becoming more attuned to and accepting of global CSR engagement [56]. Global CSR initiatives hold particular significance for enterprises in emerging economies because of their rapid international expansion and the imperative to establish credibility in global markets [57]. Moreover, modern consumers are deeply concerned about issues transcending national boundaries, such as human rights and climate change, underscoring the growing need for CSR efforts. Implementing CSR on an international level demands substantial resources, as it necessitates the consideration of unique socioeconomic and cultural factors in the target country, alongside internal alignment within the company’s management structure. Given the potential for local skepticism of the legitimacy of global CSR, it is pivotal to explore effective communication strategies to garner local support in the target country.

Only a handful of studies, however, have explored the role of the geographic proximity of CSR initiatives—how local consumers perceive a CSR effort taking place outside the country. For example, Grau and Folse [11] demonstrated the importance of donation proximity in an experiment where the participants expressed a more positive attitude and higher participation intention for donations made locally rather than nationally. This effect was valid only among those who were less involved with the cause and not among highly involved individuals. This suggests that by decreasing geographic proximity, a campaign can encourage less-involved individuals to participate in a campaign. Moreover, Grau and Folse [11] found that consumers are more likely to participate in campaigns when they believe others who are physically close to them will be directly impacted. They [11] proposed the dynamic social impact theory [58] as an explanatory mechanism. According to this theory, individuals perceive those within their immediate social sphere as more influential in their decision-making processes. Therefore, campaigns with the capacity to promptly impact nearby geographical areas not only signal a business’s commitment to creating positive social influence but also align with the principles of the dynamic social impact theory. This perspective underscores the significance of considering geographical proximity as a key factor in designing and implementing effective campaigns.

Recent studies have found similar results: Proximity increased trust toward the company [59], purchase and donation intentions [60,61], and engagement [62]. A few studies have tried to explain the tendency to evaluate a closer geographic subject more positively using personal dispositions, such as cosmopolitan orientation and ethnocentrism, but the patterns are inconclusive. Although Grinstein and Riefler [63] suggested that consumers with high cosmopolitan orientation preferred geographically distant campaigns than geographically close ones, Boulouta and Manika [60] found that a preference for close (vs. far) CSR was more prevalent among non-ethnocentric consumers.

Although previous research has shown that CSR activities located proximate to consumers tend to generate more favorable outcomes [48,64], it is unknown whether the effect of different levels of geographic proximity between consumers and a given CSR campaign may offer further explanations of the mediating role of perceived social distance. To fill this gap in the existing literature, we examined the effect of perceived social distance on the interplay between message specificity and CSR outcomes by considering the geographic proximity to the CSR campaign. The role of perceived social distance, therefore, can differ depending on the level of geographic proximity to a CSR initiative. In line with this rationale, we pose the following research question:

- RQ. Do the effects of message specificity through perceived social distance differ depending on the geographic proximity of a CSR campaign?

3. Methods

3.1. Experimental Design and Procedure

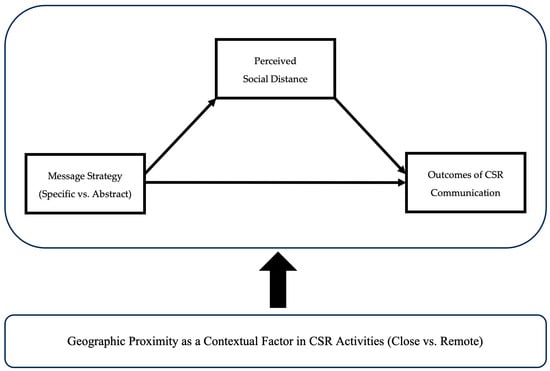

We employed message specificity (specific vs. abstract) as an independent variable, outcomes of CSR communication (CCI, WOM intention, and CSR participation intention) as dependent variables, and perceived social distance as a mediator in an experimental design (see Figure 1 for the theoretical model). Each participant read two stories. In the first step, each participant read a brief fictional news story about a corporation describing aspects, such as its business category, vision, and consumer base. In the second step, each participant read a fictional news story about a corporation’s recent corporate social responsibility (CSR) campaign that was either focused on a specific or abstract message. After reading the second news story, participants were asked to indicate their level of consumer-company identification (CCI), word-of-mouth (WOM) intention, and CSR participation intention. Demographic information was gathered at the end.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3.2. Participants

We recruited a general adult sample using a market research panel where individuals sign up to participate in online surveys. As the target audiences for CSR campaigns are typically the general population, rather than college students, who are extremely homogeneous, samples from a market research panel offer more diverse samples than do college student sample pools. All participants were given monetary compensation for their participation. A total of 293 adults in South Korea participated in the online survey. Gender was balanced (male: n = 144, 49.1%; female: n = 148, 50.5%; other: n = 1, 0.3%). Participant ages ranged from 20 to 69 years (Mage = 44.18, SD = 13.69). For education level, 17.1% (n = 50) were high school graduates or lower, 18% (n = 18) were college students, 66.2% (n = 194) completed college, and 10.6% (n = 31) had postgraduate education.

3.3. Stimuli

The stimuli were based on news stories about a corporation’s CSR campaign. We used a fictitious company name and CSR campaign name to prevent any confounding effects from participants’ previous knowledge and attitudes. We described the fictitious company, “NauB”, as leading an environmental CSR campaign, “Eco Challenge”, aimed at raising young adults’ awareness of and engagement with recycling and upcycling old items into new and interesting products.

Message specificity was manipulated to be either specific or abstract in its description of the CSR campaign. For the specific message design, the news story depicted a company’s CSR activity focusing on what they were doing in detail, such as how the company has been involved in CSR efforts and the concrete impact of the CSR program on consumers and the environment. For the abstract message design, the news story described a company’s CSR efforts broadly by presenting the goals for the CSR campaign based on their corporate vision.

3.4. Measures

Perceived social distance. To measure perceived social distance, we adopted three items using a 7-point response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) from Stephan et al. [65]. The three items were (1) “I feel familiar with NauB’s ‘Eco Challenge’ campaign”, (2) “I feel close to NauB’s ‘Eco Challenge’ campaign”, and (3) “NauB’s ‘Eco Challenge’ campaign seems like a close friend to me” (Cronbach’s α = 0.92).

Consumer-company identification (CCI). We measured perceptions of CCI with four items using a 7-point response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) adopted from Pérez and del Bosque [66]. Participants rated their agreement with the following statements: (1) “I strongly identify with NauB”, (2) “NauB fits my personality”, (3) “I feel closely linked to NauB”, and (4) “I have a strong feeling of attachment to NauB” (Cronbach’s α = 0.90).

Word-of-mouth (WOM) intention. To assess WOM intention, we adopted three items using a 7-point response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) from Wang et al. [67]: (1) “I will encourage my friends and relatives to use NauB’s products”, (2) “I will say positive things about NauB”, and (3) “I am glad to recommend NauB to others” (Cronbach’s α = 0.93).

CSR participation intention. We measured CSR participation intention with three items using a 7-point response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) adopted from Grau and Folse [11]. Participants rated their agreement with the following statements: (1) “I would be willing to participate in this CSR campaign”, (2) “I would consider taking actions in order to meet this CSR campaign goal”, and (3) “It is likely that I would contribute to this CSR campaign by getting involved” (Cronbach’s α = 0.94). Table 1 shows all of the measurement items. Table 2 shows the reliability and validity of the constructs of dependent variables.

Table 1.

Measurement items.

Table 2.

Reliability and validity of constructs of dependent variables.

3.5. Manipulation Checks

To check the message specificity (specific message vs. abstract message) manipulation, we adopted four items from Connors et al. [68]. The four bipolar items utilized a 7-point scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.902): “According to the article, NauB’s CSR campaign appears to be…” (1) abstract–concrete, (2) ambiguous–clear, (3) not easy to imagine–easy to imagine, and (4) not descriptive–descriptive. A t-test analysis revealed that participants correctly identified the conditions to which they were assigned (Mspecific = 5.15, SD = 1.09; Mabstract = 3.99, SD = 1.57; t = −6.533, df = 140.99, p < 0.001).

The manipulation checks for geographic proximity (close vs. remote) used the following six items on a 7-point scale (strongly disagree–strongly agree; Cronbach’s α = 0.883): (1) “NauB’s ‘Eco Challenge’ campaign has been carried out domestically”, (2) “NauB’s ‘Eco Challenge’ campaign has been carried out internationally” (reverse coded), (3) “NauB’s ‘Eco Challenge’ campaign targets young people in the home”, (4) “NauB’s ‘Eco Challenge’ campaign targets young Vietnamese people” (reverse coded), (5) “NauB’s ‘Eco Challenge’ campaign seems to be taking place close to me”, and (6) “NauB’s ‘Eco Challenge’ campaign seems to be taking place far away from me” (reverse coded). A t-test analysis revealed that participants correctly identified the conditions to which they were assigned (Mclose = 4.80, SD = 0.99; Mremote = 2.37, SD = 1.03; t = 20.642, df = 291, p < 0.001).

4. Results

H1a predicted the effect of message specificity on consumer-company identification (CCI). The results support H1a, indicating a significant effect of message specificity on CCI [F (1, 291) = 17.676; p < 0.001]. The specific message generated a higher CCI (M = 4.26, SD = 1.06) than the abstract message (M = 3.73, SD = 1.17). H1b predicted the effect of message specificity on WOM intention, and there was a significant main effect of message specificity on WOM intention [F (1, 291) = 11.252; p < 0.001]. The specific message generated higher WOM intention (M = 4.70, SD = 1.14) than the abstract message (M = 4.20, SD = 1.29). H1c predicted the effect of message specificity on CSR participation intention, and there was a significant effect of message specificity on CSR participation intention [F (1, 291) = 14.363; p < 0.001]. The specific message also generated higher CSR participation intention (M = 4.62, SD = 1.08) than the abstract message (M = 4.08, SD = 1.28). Therefore, H1a, H1b, and H1c were all supported. Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics of the dependent variables—CCI, WOM intention, and CSR participation intention.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of dependent variables.

H2a predicted that perceived social distance mediates the effect of message strategy (specific vs. abstract) on consumer-company identification (CCI). A mediation analysis was conducted using the PROCESS macro (Model 4) for SPSS [69]. The effect of message strategy was a significant predictor of perceived social distance (B = 0.50; SE = 0.15, p < 0.01). The results also indicate that perceived social distance significantly mediated the relationship between message strategy and CCI (B = 0.34; SE = 0.11, 95% CI = [0.13, 0.55], excluding zero). Message strategy was no longer a significant predictor of CCI (B = 0.19; SE = 0.10, p > 0.05) when the mediator, perceived social distance, was inserted (B = 0.68; SE = 0.04, p < 0.001), suggesting full mediation.

H2b predicted that perceived social distance mediates the effect of message strategy (specific vs. abstract) on WOM intention. The results indicate that perceived social distance significantly mediated the relationship between message strategy and WOM intention (B = 0.31; SE = 0.10, 95% CI = [0.14, 0.51], excluding zero). Moreover, message strategy was no longer a significant predictor of WOM intention (B = 0.18; SE = 0.12, p > 0.05) when the mediator, perceived social distance, was inserted (B = 0.63; SE = 0.05, p < 0.001), suggesting full mediation.

H2c predicted that perceived social distance mediates the effect of message strategy (specific vs. abstract) on CSR participation intention. The results indicate that perceived social distance significantly mediated the relationship between message strategy and CSR participation intention (B = 0.29; SE = 0.10, 95% CI = [0.11, 0.48], excluding zero). In addition, perceived social distance had a significant effect on CSR participation intention (B = 0.59; SE = 0.05, p < 0.001). Message strategy was also a significant predictor of CSR participation intention (B = 0.25; SE = 0.12, p < 0.05), suggesting partial mediation. Table 4 shows the mediation results of perceived social distance.

Table 4.

Mediation of perceived social distance (PSD).

RQ asked whether the mediating role of perceived social distance varies depending on geographic proximity as a contextual factor in CSR activities (close CSR vs. remote CSR). First, we tested the mediation effect of perceived social distance in the close CSR condition (n = 146) using the same PROCESS macro (Model 4) for SPSS [69]. The results indicated that perceived social distance significantly mediated the relationship between message strategy and CCI (B = 0.34; SE = 0.18, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.71], excluding zero). Message specificity was still a significant predictor of CCI (B = 0.28; SE = 0.13, p < 0.05), suggesting partial mediation.

Similarly, perceived social distance significantly mediated the relationship between message strategy and WOM intention (B = 0.33; SE = 0.16, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.66], excluding zero). Message specificity was still a significant predictor of CCI (B = 0.34; SE = 0.15, p < 0.05), suggesting partial mediation.

Perceived social distance also significantly mediated the relationship between message strategy and CSR participation intention (B = 0.29; SE = 0.15, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.60], excluding zero). Message specificity was still a significant predictor of CSR participation intention (B = 0.40; SE = 0.14, p < 0.01), suggesting partial mediation.

Second, we tested the mediation effect of perceived social distance in the remote CSR condition (n = 147) using the same PROCESS macro (Model 4) for SPSS (Hayes, 2013). The results indicated that perceived social distance significantly mediated the relationship between message strategy and CCI (B = 0.33; SE = 0.13, 95% CI = [0.08, 0.59], excluding zero). Message specificity was no longer a significant predictor of CCI (B = 0.09; SE = 0.14, p > 0.05) when the mediator, perceived social distance, was inserted (B = 0.62; SE = 0.05, p < 0.001), suggesting full mediation.

Similarly, perceived social distance significantly mediated the relationship between message strategy and WOM intention (B = 0.30; SE = 0.12, 95% CI = [0.06, 0.55], excluding zero). Message specificity was no longer a significant predictor of WOM intention (B = 0.04; SE = 0.18, p > 0.05) when the mediator, perceived social distance, was inserted (B = 0.55; SE = 0.07, p < 0.001), suggesting full mediation.

Perceived social distance also significantly mediated the relationship between message strategy and CSR participation intention (B = 0.30; SE = 0.13, 95% CI = [0.06, 0.58], excluding zero). Message strategy was no longer a significant predictor of CSR participation intention (B = 0.10; SE = 0.18, p > 0.05) when the mediator, perceived social distance, was inserted (B = 0.56; SE = 0.07, p < 0.001), thus suggesting full mediation. Table 5 shows the mediation results of perceived social distance depending on CSR proximity.

Table 5.

Mediation of perceived social distance (PSD) depending on CSR proximity.

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of Results

The present study examines the role of message specificity in generating the intended CSR outcomes and explores the mediating role of perceived social distance in the relationships between message specificity as a message strategy and perceptions and behavioral intentions. Ultimately, the results reveal that the more specific the messages in the CSR communication, the greater the CCI, WOM, and CSR participation intention. Additionally, perceived social distance accounted for the positive association between message specificity and the three dependent variables.

As supported by the previous literature [9,20,22,70], the current study showed the positive effect of specific messages compared to abstract messages. While scholars have primarily focused on the role of CSR message specificity in consumer perceptions of company trustworthiness [68,71], our study expands the understanding of message specificity by investigating its effects on CCI, WOM intention, and CSR participation intention, which have not previously been extensively studied.

In addition, the present study explores the mediating role of perceived social distance in the relationships between message strategy and CSR communication outcomes. Although previous research has recognized the positive effects of message specificity on consumer evaluations [9,17,20,21,22], the underlying mechanisms and, particularly, the mediating role of perceived social distance, have not been fully elucidated. By employing the theoretical framework of CLT [43], we have shed light on how perceived social distance mediates the effectiveness of message specificity in CSR communication.

According to Trope and Liberman [39], social distance refers to people’s subjective perceptions of similar others as belonging to their in-group and dissimilar others as belonging to their out-group. As such, people are likely to interpret a CSR campaign’s message either concretely (close social distance) or abstractly (distant social distance), depending on how relatable or unrelatable they believe it to be to them. According to the current research, message specificity as a communication strategy may improve consumers’ perceptions of CSR campaigns via the psychological mechanism of perceived social distance to the CSR campaign message.

This study applies perceived social distance not to companies or specific CSR topics, as previous research based on involvement and familiarity has been conducted [54,72,73], but rather to consumers’ perceptions of a given CSR campaign. By focusing on the perceived social distance from the CSR campaign itself, our research provides a nuanced perspective distinct from involvement or familiarity measures in CSR communication.

Intuition suggests that a more specific communication of CSR campaigns inherently fosters greater relatedness, subsequently encouraging CSR involvement and action. Despite the apparent logic of this connection, there is a dearth of empirical studies systematically testing this relationship, preventing its evolution into a robust theoretical framework. Our research fills this important vacuum by considerably adding to theory development in the domain of specificity as a messaging strategy. Our work, which is based on CLT, goes beyond mere observation by offering a precise theoretical explanation for the observed phenomena. This both enhances our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of why a specific message is perceived more positively and lays a solid foundation for future theory-building endeavors in the realm of CSR message strategies. By bridging the gap between intuition and empirical evidence, our research paves the way for more nuanced and effective strategies in the ever-evolving landscape of CSR.

5.2. Practical Implications

Given the increasing complexity and diversity of CSR campaigns in terms of topics, target audiences, and impacts, practitioners will find that considering perceived social distance can offer valuable insights for crafting effective CSR messages. Additionally, our findings highlight the importance of reducing perceived social distance, particularly in the context of international CSR campaigns occurring in far geographic proximity.

More specifically, the explanatory power of perceived social distance provides insights into how to make CSR communication efforts successful on a message level, as perceived social distance, unlike involvement or familiarity, is a fluid perception that can be modified by disseminating messages within a short period of time. To make CSR messages more specific, companies can incorporate specific CSR themes, a thorough description of the CSR campaign, information on the campaign’s beneficiaries, and the expected outcomes of the CSR campaign. Additionally, CSR managers can use narratives that go into specifics about the benefits that the CSR campaign can offer to particular participants to develop a CSR campaign that reduces the perceived social distance between customers and the CSR campaign.

Furthermore, our research demonstrates that reducing perceived social distance through message specificity is even more effective for geographically distant CSR cases, so when a company conducts an international CSR campaign, it is even more important to develop specific and detailed information, including the CSR background and what is behind its mission as well as the anticipated benefits on the individual and societal levels. Notably, multinational companies can enhance the specificity and richness of their CSR messages by considering the convergence of cultural contexts between the regions where the CSR initiatives are communicated and the region where they are executed. This approach underscores the importance of aligning the cultural nuances and sensitivities of both regions to ensure that CSR messages resonate authentically with customers by shortening the perceived social distance between the regions.

From a management perspective, elaborating specific CSR information is not highly resource-intensive work and simply needs to be strategically streamlined in the CSR planning. Therefore, using message specificity as a CSR communication strategy can increase the effectiveness of CSR planning and execution and, ultimately, raise the value of CSR initiatives. Although corporations have rights and control over what to communicate and how to selectively frame their CSR messages, reputational benefits from CSR initiatives can be obtained only when consumers are aware of corporate endeavors and believe them to be accurate [74].

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations. First, it only examines one type of CSR campaign message focusing on environmental issues. Future studies can use different types of CSR initiatives to more comprehensively capture the interplay of message specificity as a message factor and perceived social distance in influencing consumer interpretations of CSR messages. Second, as an experimental design, we created CSR campaign messages for one fictitious company. Future work should replicate our study using CSR campaigns from multiple companies and using real-world companies, to improve the external validity of our findings. Third, CSR-related information may be perceived differently depending on the time of exposure due to different news coverages and policy changes; therefore, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution. Lastly, this study uses a sample of Korean adults, and East Asians are known to be more holistic in their information processing compared to Westerners [75,76]. Therefore, our sample might have recognized more contextual signals in the CSR campaigns than a sample of Westerners would, which could have affected the results of our study. Future research should replicate this study in other cultural contexts for better generalizability.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the impact of message specificity in CSR communication on consumer outcomes and explored the mediating role of perceived social distance. The results supported our hypotheses, revealing that specific messages in CSR communication led to higher levels of CCI, WOM intention, and CSR participation intention than did abstract messages. The perceived social distance mediated the relationship between message specificity and the outcome variables, indicating its crucial role in shaping consumer perceptions and behavioral intentions. The study contributes theoretically by expanding the understanding of message specificity beyond trustworthiness and exploring its effects on CCI, WOM intention, and CSR participation intention. Additionally, the mediating role of perceived social distance, rooted in CLT, offers insights into the psychological mechanisms involved in CSR communication. On a practical level, the findings suggest that practitioners should consider perceived social distance when crafting CSR messages, especially in international campaigns. Reducing perceived social distance through specific and detailed CSR information can enhance the effectiveness of communication efforts, particularly in geographically distant cases. This study underscores the importance of aligning cultural contexts in multinational campaigns to ensure authentic resonance with consumers and emphasizes the strategic value of message specificity in enhancing the overall effectiveness and value of CSR initiatives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K., H.J.O. and S.Y.L.; methodology, J.K., H.J.O. and S.Y.L.; formal analysis, J.K. and H.J.O.; interpretation of the results, J.K., H.J.O. and S.Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K. and H.J.O.; writing—review and editing, J.K., H.J.O. and S.Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Incheon National University Research Grant in 2019.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted with the approval of Incheon National University, in compliance with the guidelines and regulations of the university institutional review board for the method.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

List of Abbreviations

| CSR | Corporate social responsibility |

| CLT | Construal level theory |

| CRM | Cause-related marketing |

| CCI | Consumer-company identification |

| WOM intention | Word-of-mouth intention |

References

- David, P.; Kline, S.; Dai, Y. Corporate social responsibility practices, corporate identity and purchase intention: Viability of a dual-process model. J. Public Relat. Res. 2005, 17, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunig, J.E. Collectivism, Collaboration, and Societal Corporatism as Core Professional Values in Public Relations. J. Public Relat. Res. 2000, 12, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J.; Harris, K.E. Do Consumers Expect Companies to be Socially Responsible? The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Buying Behavior. J. Consum. Aff. 2001, 35, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Doing better at doing good: When, why and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2004, 47, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernev, A.; Blair, S. Doing Well by Doing Good: The Benevolent Halo of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Consum. Res. 2015, 41, 1412–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Korschun, D. The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Strengthening Multiple Stakeholder Relationships: A Field Experiment. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.; Sen, S. Maximizing Business Returns to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The Role of CSR Communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, R.E.; Lee, W. Communicating corporate social responsibility: How fit, specificity, and cognitive fluency drive consumer skepticism and response. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Lee, S.Y. Visual CSR Messages and the Effects of Emotional Valence and Arousal on Perceived CSR Motives, Attitude, and Behavioral Intentions. Commun. Res. 2019, 46, 926–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, S.L.; Folse, J.A.G. Cause-Related Marketing (CRM): The Influence of Donation Proximity and Message-Framing Cues on the Less-Involved Consumer. J. Advert. 2007, 36, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öberseder, M.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Gruber, V. “Why Don’t Consumers Care About CSR?”: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Role of CSR in Consumption Decisions. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rank, S.; Contreras, F. Do Millennials pay attention to Corporate Social Responsibility in comparison to previous generations? Are they motivated to lead in times of transformation? A qualitative review of generations, CSR and work motivation. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2021, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, K.; Saha, R.; Goswami, S.; Sekar; Dahiya, R. Consumer’s response to CSR activities: Mediating role of brand image and brand attitude. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeltz, L. Consumer-oriented CSR communication: Focusing on ability or morality? Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2012, 17, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torelli, R.; Balluchi, F.; Furlotti, K. The materiality assessment and stakeholder engagement: A content analysis of sustainability reports. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.; Eilert, M. The role of message specificity in corporate social responsibility communication. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 90, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alter, A.L.; Oppenheimer, D.M. Easy on the mind, easy on the wallet: The roles of familiarity and processing fluency in valuation judgments. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2008, 15, 985–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, B.; Grimes, A. How Claim Specificity Can Improve Claim Credibility in Green Advertising. J. Advert. Res. 2018, 58, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; Salmones, M.; Liu, M.T. Information specificity, social topic awareness and message authenticity in CSR communication. J. Commun. Manag. 2020, 24, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghi, I.; Rubaltelli, E.; Tedeschi, M. A strategy to communicate corporate social responsibility: Cause related marketing and its dark side. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, A.; Huang, Y.; Bortree, D.S.; Waters, R.D. Designing Social Media Fundraising Messages: An Experimental Approach to Understanding How Message Concreteness and Framing Influence Donation Intentions. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2022, 51, 832–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Attitudes and Persuasion: Classic and Contemporary Approaches; William C. Brown: Dubuque, IA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit, W.L. Argument evaluation. In Argumentation: Across the Lines of Discipline; van Eemeren, F.H., Grootendorst, R., Blair, J.A., Willard, C.A., Eds.; Foris: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1987; pp. 189–297. [Google Scholar]

- Roberson, Q.M.; Collins, C.J.; Oreg, S. The Effects of Recruitment Message Specificity on Applicant Attraction to Organizations. J. Bus. Psychol. 2005, 19, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.-C.; Hsieh, Y.-C.; Kuo, Y.-C. How to Align your Brand Stories with Your Products. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. The Process Model of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Communication: CSR Communication and its Relationship with Consumers’ CSR Knowledge, Trust, and Corporate Reputation Perception. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 1143–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.; Sen, S. Consumer–Company Identification: A Framework for Understanding Consumers’ Relationships with Companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, S.; Iglesias, O.; Singh, J.J.; Sierra, V. How does the Perceived Ethicality of Corporate Services Brands Influence Loyalty and Positive Word-of-Mouth? Analyzing the Roles of Empathy, Affective Commitment, and Perceived Quality. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 721–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, R.; Kennett-Hensel, P.A. Longitudinal Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Customer Relationships. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.W. Customer Satisfaction and Word of Mouth. J. Serv. Res. 1998, 1, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The Behavioral Consequences of Service Quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla-Pria, L.; Rodríguez-De-Dios, I. CSR communication on social media: The impact of source and framing on message credibility, corporate reputation and WOM. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2022, 27, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, C.-D.; Kim, J. The effects of CSR communication in corporate crises: Examining the role of dispositional and situational CSR skepticism in context. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, H.; Kim, S. Dimensions of corporate social responsibility (CSR) skepticism and their impacts on public evaluations toward CSR. J. Public Relat. Res. 2016, 28, 248–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kristensen, L.; Villaseñor, E. Overcoming skepticism towards cause related claims: The case of Norway. Int. Mark. Rev. 2009, 26, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné-Alcañiz, E.; Currás-Pérez, R.; Ruiz-Mafé, C.; Sanz-Blas, S. Consumer behavioural intentions in cause-related marketing. The role of identification and social cause involvement. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2010, 7, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broniarczyk, S.M.; Alba, J.W. The Importance of the Brand in Brand Extension. J. Mark. Res. 1994, 31, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. The Psychology of Transcending the Here and Now. Science 2008, 322, 1201–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Temporal construal. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 110, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N.; Wakslak, C. Construal Levels and Psychological Distance: Effects on Representation, Prediction, Evaluation, and Behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2007, 17, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Trope, Y.; Stephan, E. Psychological Distance. In Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles; Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; Volume 2, pp. 353–381. [Google Scholar]

- Linville, P.W.; Fischer, G.W.; Yoon, C. Perceived covariation among the features of ingroup and outgroup members: The outgroup covariation effect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglio, S.J.; Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. The Common Currency of Psychological Distance. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 22, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, S.-Y.; Cho, E. CSR ads matter to luxury fashion brands: A construal level approach to understand Gen Z consumers’ eWOM on social media. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 26, 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lii, Y.; Wu, K.; Ding, M. Doing Good Does Good? Sustainable Marketing of CSR and Consumer Evaluations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.; Yang, Y. The effect of authenticity and social distance on CSR activity. Soc. Responsib. J. 2016, 12, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K.K.; Tao, C.-W.W.; Slevitch, L. Restaurant chain’s corporate social responsibility messages on social networking sites: The role of social distance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.J.; Winterich, K.P. Can Brands Move in from the Outside? How Moral Identity Enhances Out-Group Brand Attitudes. J. Mark. 2013, 77, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E.; Bettman, J.R. Self-Construal, Reference Groups, and Brand Meaning. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakis, I.G.; Painesis, G. The Impact of Psychological Distance and Construal Level on Consumers’ Responses to Taboos in Advertising. J. Advert. 2018, 47, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y.; Choi, C.-W.; Overton, H.; Kim, J.K.; Zhang, N. Feeling Connected to the Cause: The Role of Perceived Social Distance on Cause Involvement and Consumer Response to CSR Communication. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2022, 99, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, D.; de Andrade, L.M.; Negrão, A. How motivations for CSR and consumer-brand social distance influence consumers to adopt pro-social behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 36, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.S. Explicating firm international corporate social responsibility initiatives. Rev. Int. Bus. Strat. 2020, 30, 515–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Mirshak, R. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Theory and Practice in a Developing Country Context. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 72, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latané, B. Dynamic Social Impact: The Creation of Culture by Communication. J. Commun. 1996, 46, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, V.S.; Vafeiadis, M.; Bober, J. Greening Professional Sport: How Communicating the Fit, Proximity, and Impact of Sustainability Efforts Affects Fan Perceptions and Supportive Intentions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulouta, I.; Manika, D. Cause-Related Marketing and Ethnocentrism: The Moderating Effects of Geographic Scope and Perceived Economic Threat. Sustainability 2022, 14, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterich, K.P.; Mittal, V.; Ross, W.T. Donation Behavior toward In-Groups and Out-Groups: The Role of Gender and Moral Identity. J. Consum. Res. 2009, 36, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillani, A.; Kutaula, S.; Leonidou, L.C.; Christodoulides, P. The Impact of Proximity on Consumer Fair Trade Engagement and Purchasing Behavior: The Moderating Role of Empathic Concern and Hypocrisy. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169, 557–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinstein, A.; Riefler, P. Citizens of the (green) world? Cosmopolitan orientation and sustainability. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2015, 46, 694–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groza, M.D.; Pronschinske, M.R.; Walker, M. Perceived Organizational Motives and Consumer Responses to Proactive and Reactive CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, E.; Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. Politeness and psychological distance: A construal level perspective. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, A.; del Bosque, I.R. Corporate social responsibility and customer loyalty: Exploring the role of identification, satisfaction and type of company. J. Serv. Mark. 2015, 29, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Xue, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. Green image and consumers’ word-of-mouth intention in the green hotel industry: The moderating effect of Millennials. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, S.; Anderson-MacDonald, S.; Thomson, M. Overcoming the ‘Window Dressing’ Effect: Mitigating the Negative Effects of Inherent Skepticism Towards Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 599–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grau, S.L.; Garretson, J.A.; Pirsch, J.; D, P. Cause-Related Marketing: An Exploratory Study of Campaign Donation Structures Issues. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2007, 18, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, W.; Su, C. Going green: How different advertising appeals impact green consumption behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2663–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, S.; Khamitov, M.; Thomson, M.; Perkins, A. They’re Just Not That into You: How to Leverage Existing Consumer–Brand Relationships Through Social Psychological Distance. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. The Process of CSR Communication—Culture-Specific or Universal? Focusing on Mainland China and Hong Kong Consumers. J. Bus. Commun. 2022, 59, 56–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T.; Holladay, S.J. The pseudo-panopticon: The illusion created by CSR-related transparency and the internet. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2013, 18, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boduroglu, A.; Shah, P.; Nisbett, R.E. Cultural Differences in Allocation of Attention in Visual Information Processing. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2009, 40, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chee, M.W.L.; Zheng, H.; Goh, J.O.S.; Park, D.; Sutton, B.P. Brain Structure in Young and Old East Asians and Westerners: Comparisons of Structural Volume and Cortical Thickness. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2011, 23, 1065–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).