Abstract

This study aims to present a methodological framework for estimating the recreational value as part of the ecosystem’s services provided by the Sudanese forests. The number of visitors ready to pay for the forest’s services has been analyzed using the individual travel cost method (ITCM). The data were collected using questionnaires with 640 visitors randomly participating at the forest site, and respondents’ results were analyzed using SPSS software v21. Further analysis of ITCM was performed using analysis of moment structure. The linear regression model is used to estimate the effects of variables, like socioeconomic variables, on the frequency of the visits to assess the recreational value of the forest site. The results showed that the consumer’s excess for each visitor was 21,500 Sudanese pounds (SDG), and travel costs, age, income, distance, and family size of visitors affect the recreational use of the site. Most of the visitors were students, with the majority of their ages ranging between 21 and 30. An additional discovery indicated that higher-income visitors were more willing to travel. These encouraging findings are a helpful guide for planning the future management of forests for recreational uses. This meant that forests offer great recreational value, which might help the Forestry Office ensure that natural forests are planned for and used sustainably.

1. Introduction

Ecosystem service (ES) is defined as ecosystems’ direct and indirect contributions to human well-being, impacting our survival and quality of life []. There are four types of ecosystem services: provisioning, regulating, cultural, and supporting services [,]. The ES concept was developed to measure the intricate relationship between people and nature []. This approach can be employed to study the value of different ES for human well-being []. Humans generally derive benefits from forests associated with the services provided by forests []. Resources with many uses include forests and forest lands []. As such, forests offer a wide range of goods and services, including recreational activities, biodiversity, landscaping, and carbon sequestration, in addition to timber and wood-related items [,]. Ecosystem services, which encompass both the direct and indirect benefits of ecosystems to human well-being, demonstrate how well-suited a landscape is to sustaining human life [,,]. Recreational activities are mainly intended to amuse or provide fun; consider them to provide opportunities for mental stimulation [].

The benefits and effects of natural protected areas that are also destinations for recreation must be distinctly outlined and proven. However, as most visitors to natural recreational sites only pay a small entrance fee, which reduces their extreme readiness to pay, the worth of these resources to the general public is unclear and must be estimated using non-market valuation techniques []. The demand for outdoor recreation is rising along with the growing population. Still, due to the depletion of natural resources and the scarcity of funding, it was essential to assess the economic advantage of recreation areas to ensure that such resources could remain as independent as feasible [].

Sudan is blessed with a wide range of ecosystems that are significant on a national and international scale. These include forests, dry and semi-arid rangelands, and a diverse range of natural and artificial wetlands, from rain pools to crater lakes and riverine to coastal ecosystems. Forests in Sudan are essential in integrated land use systems in terms of economic development, environmental protection, supporting the demands of multiple stakeholders, and sustaining livelihoods [,]. Recreation is merely one of the many services offered by ecosystems []. Users’ value of recreation in nature can be significant, although it is not reflected in market prices and is presented as a semi-public good []. Recreation is one of the many functions of a forest; Al-Sunut Forest Reserve is the only urban forest in Khartoum State. Here, people can go for walks, picnics, bird and animal watching, enjoy the fresh air, and gather valuable resources like tree seeds and deciduous wood. The forest is a significant site for students as well. The Sudanese civil code ensures the general public’s right to freedom and the reserve’s recreational purposes in Khartoum []. Although it was officially declared a forest reserve in 1932 and a bird reserve in 1945, this forest has been subjected to several attempts to clear its trees and use its prime lands for investment [,].

Recreation is a non-market service and, hence, not readily observable; economic valuation methods have been developed to determine the demand for that specific environmental service []. Non-market forest goods satisfy social needs at the same time while also being produced, but they are not accessible to market procedures of valuation [,]. Thus, consumers’ assessments of the advantages correlate to the value of these goods and services, and their willingness to pay for the forest’s natural values dictates the cost of ecosystem goods and services []. Natural ecosystems provide vital life-supporting functions on which human civilization depends [,]. Natural ecosystems can supply huge advantages, such as clean air, water, food, and fuel, that can improve the quality of life and advance human civilization []. ES are the rewards people enjoy from ecosystems, which are increasingly regarded for contributing to human well-being []. From a local to a global scale, forests and trees offer essential services and goods, such as the provision of medicine, the regulation of water, and sacred sites [,].

The Travel Cost Method (TCM) is the most popular indirect technique for determining the value of natural areas used for recreation [,,,]. Harold Hotelling initially suggested this approach as a possible way of evaluating national parks in the 1930s. Clawson and Kentsch developed the Hotelling Method, and they named it the “Travel Cost Method” []. TCM is predicated on the idea that an individual’s overall spending on a recreational site indicates their willingness to pay for that particular site. The deciding factor is how often a specific recreation site is visited in a given time frame (usually one year). Estimating consumer surplus involves comparing spending to the number of visits []. The individual travel cost method (ITCM) and the zonal travel cost method (ZTCM) are two different uses of the travel cost method [].

Economic valuation aims to give quantifiable values to the goods and services that environmental resources supply [], whether or not there is market pricing. Whether or not we have made any payments, the economic value of a good or service describes the resource’s value in producing those goods []. Therefore, the economic assessment considers the resource’s existing stock, direct costs and flows to the communities, and the environmental services it offers [,]. Reviews of ecosystem services play a vital role in the development of knowledge about the state of the environment and the sustainable management of natural capital []. Therefore, it is crucial to quantify recreational sites’ economic benefits to allocate finite resources in the most optimal potential approach [].

The main objective of this study is to estimate the economic value per trip per visitor for visitors who take trips to Al-Sunut Forest Reserve using the individual travel cost method. The basic premise of this theory is that the costs spent by an individual to enter the Al-Sunut Forest indicate the area’s economic value. In this study, the researcher assesses the function of encouraging site visits after gathering the appropriate questionnaires and then calculates the consumer surplus, which is equal to the economic value of the recreational site. The second objective is to identify factors that affect recreation and to understand the recreational value of this forest reserve. This is important because it will inform the nature reserve managers about visitors’ challenges and obstacles.

As a result, the TCM was used in this study to assess the economic value per trip per visitor for recreation in Al-Sunut Forest. Because the TCM is effective and widely used for evaluating recreational value and policies related to recreational activity planning, numerous studies have used the TCM to analyze recreational value [,,]. Other statewide studies (e.g., [] in Sweden and [] Finland) focus on outdoor or nature-based recreation in general, demonstrating that forests constitute the primary source of recreation benefits in these nations. TCMs are classified as ZTCM, random utility model (RUM), and ITCM. The ITCM assesses the value of a recreational activity place using survey data from personal visits. It provides more information about individual visitors and produces more precise results than the ZTCM []; in this study, we used the ITCM to obtain information about the estimation of recreational values and the characteristics of recreation sites in Al-Sunut Forest that were considered. Throughout the paper, we will use ‘TCM’ as shorthand for ‘ITCM’.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

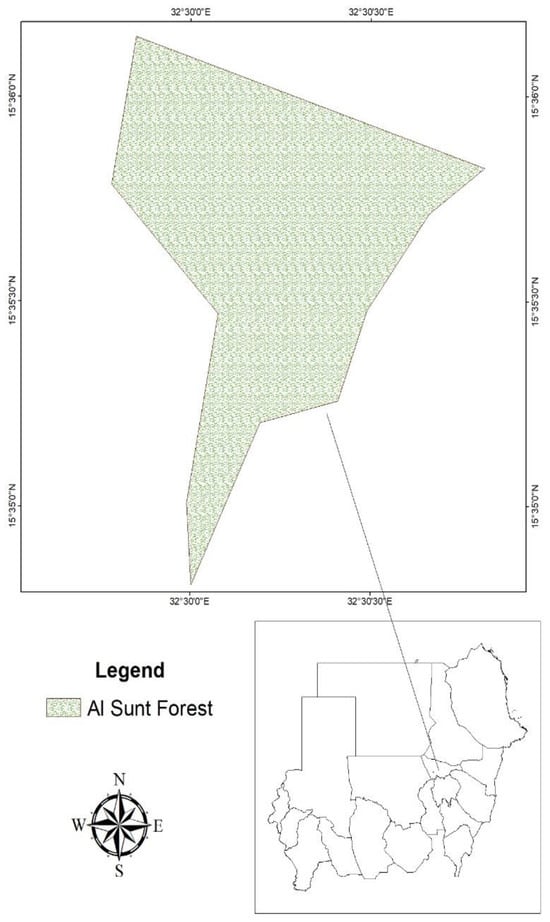

The study was conducted in Al-Sunut Forest Reserve Figure 1, Khartoum State, Sudan. Khartoum State—the capital of Sudan—is located in the sub-Saharan Africa region []. It was founded in 1820 AD and later became northeastern Africa’s national capital. Its development is concentrated at 15°33′06″ N latitude and 32°31′56″ E longitude, and it is 380 m above sea level on average. The city is one of the most important towns in Sudan due to its strategic location at the confluence of the Blue and White Niles and its central location within the country []. The state has experienced outstanding urbanization over the past few decades, which has created an urban heat island effect. The state comprises the three most significant towns of Khartoum, Khartoum North, and Omdurman []. Khartoum State has a semi-arid climate, with yearly rainfall between 150 and 250 mm. The average monthly temperature ranges from 25 °C in December to 45 °C in May, and the Nile flood season coincides with the rainy season []. Al-Sunut Forest Reserve is strategically located at the confluence of the White and Blue Nile within the latitude of 15°34′ N–15°35′ N, longitude 32°30′ E–32°29′ E, covering an area of about 164 hectares, representing one of the rare remaining urban forests in Sudan []. It is an important educational site for students and researchers and the only natural recreation area available to the people of the capital. Migratory bird species utilize this area to fly from Eurasia to Africa, making it an essential educational site. The White Nile’s bank is dedicated to the bird sanctuary, which covers 15 km and includes islands and cultivated areas [].

Figure 1.

The map of Sudan shows the Al-Sunut Forest Reserve site (taken from DIVA-GIS version 7.5 (https://www.diva-gis.org/Data, accessed on 19 January 2020) and extracted to our study area in ArcGIS 10.5).

2.2. Data Collection and Questionnaire Design

2.2.1. Data Collection of the Field Survey

A structured questionnaire is designed to obtain the flight data required for the ITCM application. The participants were chosen through convenience sampling []. The data for this study were collected by questionnaires with the visitors inside the Al-Sunut Forest from January to March 2020. It began with an informed consent statement indicating the purpose of the study, ensuring confidentiality, and arousing people’s interest. The study is based on responses only from participants who took trips to the Al-Sunut Forest for recreation. This is because the study focuses on using nature values, and ITCM can only be used to capture use values.

2.2.2. Construction of the Questionnaire

The questionnaire contained questions to determine the socio-economic characteristics of the visitors and the travel costs involved when visiting the forest site. A beta test was conducted on 30 visitors to check the suitability of the questions and to evaluate the response of the visitors to filling out the questionnaire. Accordingly, some questions were deleted while others were modified. Questionnaires were randomly distributed to visitors to the forest site, with 640 surveys being questioned during weekdays and weekends.

2.2.3. Selection of Respondents

The questionnaire consisted of four parts. The first part included socio-economic information such as gender, age, education, housing, occupation, and years of experience. The second part about respondents’ opinions included knowing the location of the forest, the number of visits, the number of trips made and planned in the last and next year, and the purpose of the visit. The third part included information about the monthly income, the source of income, and knowledge of the alternative activities that he would undertake if he did not come for this visit. The fourth part included financial expenses, the different types of travel vehicles they used, distance, round-trip costs, and costs incurred within the forest site, such as water, food, and other services. The questionnaire concluded by questioning the visitors’ opinions about the importance of the forest and its role in society and stating the obstacles they face inside the forest.

The primary study questions are personal information such as (gender, age, family size, educational level, etc.); How many kilometers is your residence from Al-Sunut Forest recreation? For how many years have you known Al-Sunut Forest recreational sites? How many trips did you plan to take to the Al-Sunut forest recreation sites during the last 12 months? How many times have you visited Al-Sunut Forest recreation? How long do you usually stay or want to stay at Al-Sunut Forest recreational sites? Do you have a monthly income source/s? Which mode of transport did you use to and from the Al-Sunut Forest recreation site? On average, what are your total recreational costs at the Al-Sunut Forest recreational site?

2.3. Methods

Individual Travel Cost Method (ITCM)

This study measures the recreational value of the Al-Sunut Forest from the individual travel method of travel expenses. The travel cost method is one of the techniques used to estimate the value of recreational sites using consumption behavior in related markets [,]. In other words, this method is a nonmarket procedure in which a recreational site value is estimated by considering how much people spend to access the site. TCM’s basic concept is that the costs of traveling to and from an area for recreation are correlated with the destination’s value and visitors’ willingness to spend time on the site []. It is used to examine empirical models that spotlight the relationship between the amount of time required for recreation and the expense of travel [].

One of the value systems for recreational sites that have been used the most widely recently is ITCM. The basic principle of this theory is that a trip’s cost is equivalent to a destination’s value [,]. Other aspects of a person’s life, such as their family’s socioeconomic status and income, the availability of substitute destinations, and their awareness of environmental conditions, influence their travel choices []. Then, the following is done to generate the individual demand function:

The recreational value of a forest site is estimated using a linear function by estimating the effects of explanation variables, such as economic and social variables, on the number of visits, as shown below (Equation (1)):

where:

is the number of visits by individual I to a recreational site annually.

is the cost of each visit’s travel. This includes the total entry price, transportation, food, time (opportunity cost), and other expenses specified in the questionnaire.

is the hypothetical ‘entry price’ paid by visitors to the park.

are socioeconomic variables like income, education level, age, choices, and close alternatives defining specific visitors [,].

In its simplest form, the single site model is (Equation (2)):

where r is the number of trips taken by an individual in a season to the site, and is the cost to travel to the site. Like any demand function, one expects an opposite relationship between the quantity required and the quantity provided (i.e., trip (r) and price (trip cost)). Living nearby reduces the cost of traveling to the site for such individuals and, r all else constant, probably takes more trips. An individual’s desire for recreational travel cannot be explained by trip spending alone [].

For an accurate and trustworthy assessment of the site’s recreational value, the sample size (number of questionnaires) is an important issue. Analysis was initiated by descriptive and exploratory manipulation of the data obtained from the study. Frequencies and percentages were used to determine socioeconomic factors influencing an individual’s decision to visit the forest, such as travel costs, age, income, and educational level. Data from 640 questionnaires were entered, cleaned, processed, and analyzed using SPSS version 21, and further analysis was performed for ITCM. Regression analysis and unobserved factors were evaluated against the number of annual visits as a dependent variable.

ITCM is used for estimating the economic values of ecosystem goods and services. It is generally utilized for assessing the monetary value of recreational assets such as national parks and forest sites []. ITCM is based on the assumption that travel costs represent the price of access to a recreational area. People’s willingness to pay to visit a site is thus estimated based on the number of trips they make at different travel costs [,]. This method is known as a “showed choice” approach because it “reveals” visitors’ willingness to pay through their habits of spending [,].

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Sample Characteristics of the Respondents

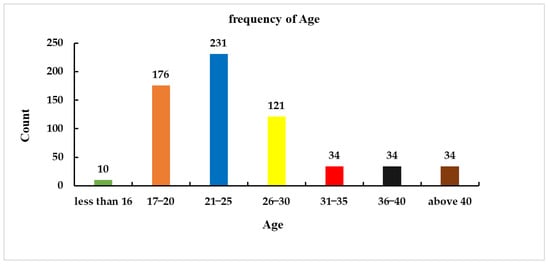

Questionnaires were used to determine the recreational value of the Al-Sunut Forest. The first part includes the socio-economic status of visitors, and the second part concerns questions about the travel distance, the type of vehicle, the period, and the cost spent in the forest site; the third part discusses the monthly income, the number of annual visits and the duration of stay within the forest site. This analysis uses data from 640 questionnaires completed by visitors inside the Al-Sunut Forest site. The descriptive statistics of the socioeconomic characteristics of the Al-Sunut Forest visitors are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The results indicate no gender difference in the visitors and that their proportion was almost equal. Young people represent more than half of the visitors between the ages of 21 and 30, and senior visitors over 30 represent 16%. On the other hand, 72% of the visitors were unmarried, representing the vast majority. Additionally, nearly half of the respondents live in a medium-sized household. Since most visitors are young people, this result shows that young people are more interested in visiting recreational sites, and this is in agreement with Fixon and Pangapanga (2016) [], who showed that almost all visitors to Lengwe National Park in Malawi are young and aged between 31 and 50 years.

Figure 2.

The age frequency of visitors to the Al-Sunut Forest site.

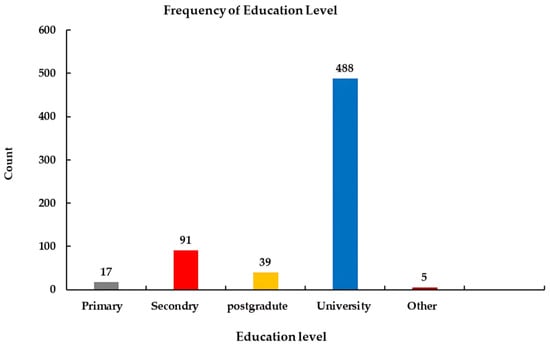

Figure 3.

Education level of visitors in Al-Sunut Forest site.

Education level and employment figures indicated that more than three-quarters of the visitors were undergraduate students. Over 35% of the participants’ permanent dwellings were within 10 to 19 km of the forest—participants who reside within 20 to 29 miles account for 30%. Most visitors stayed near the site, with 57% of participants spending one hour or less to get to the entertainment site. According to the study’s results, most visitors are middle-aged groups and singles, indicating that these age groups consider this recreational site more appealing. Figure 2 and Figure 3 analyze some sample characteristics of the respondents (Age and education level).

3.2. Analysis Content of Individual Travel Cost Method

This subsection elaborates on the respondents’ opinions on the site and their visits. The results showed that more than 40% and 28% of the respondents have 2–6 and 7–11 years of awareness about the recreation site, respectively (Table 1). More than 92% of the respondents visited the recreation site last year at least once, and a third of them visited multiple times (3 to 6 times), while 21% visited the recreation site more than 15 times. Moreover, 71% of the respondents had various trips between the recreation Plan trips and recreation tips they took during the 12 months. A set of reasons were stated for the variation between the planned and the actual visits. Limited leisure time was the most frequently stated reason, followed by income limitation. This indicates that the individual’s previous awareness of the location of the site, the level of income, and availability of leisure time influence the number of trips; in other words, the more there is prior awareness of the location of the site and the higher the level of income, the higher the number of trips to the forest site. This latter result is in line with Kassaye (2019). Recreational areas that, visitors’ monthly income is considered one of the main variables positively affecting the number of visits [].

Table 1.

Analysis content of individual travel cost method in Al-Sunut Forest site.

Also, the results showed that the time enjoyed in the forest recreational site ranges between 3 to 11 h, with the majority of visitors spending about 3 to 6 h per visit, representing 68%. Most of their visits are organized in groups of 3 to 6 and 7 to 11 people, with the friend groups representing three-quarters of them Table 1. Less than 60% frequently prefer weekend recreation, followed by public holidays (33%). Approximately 58% of the visitors prefer to carry their visits in the summer, while 36% prefer the winter. Undoubtedly, the recreational sites are mostly filled with rainwater in autumn. Hence, just 6% of visitors said they like to visit recreational areas in autumn.

3.3. Analysis of Opportunity Cost of Time

Results of Table 2 showed that almost all visitors have a monthly income, but more than 60% of them have a monthly income of less than 5000 SD; it should be mentioned that 1 US dollar was equivalent to 55 Sudanese pounds when the necessary data for this study was gathered in 2020, according to the exchange rates provided by the Sudanese central bank in March of that year []. This is in line with the reality that most of the visitors are students. The monthly income of the visitors ranges between 5000 and 9000 SD, representing 29%. Moreover, more than half of the respondents’ monthly payments depend on the support and remittances of their family, relatives, friends, and rent (house, property for business activities). Visitors have a monthly income from business activities, representing more than 25%. More than 53% of the visitors were most likely to do non-payable work if they were not on this trip.

Table 2.

Analysis of opportunity cost of time.

3.4. Analysis of Money Expenditure

According to the results (Table 3), more than 83% of the visitors favor public transportation. All visitors prefer to visit recreation areas that offer free entry. The transport expense is sufficiently justified in the residential area because fewer than 70% of visitors have transportation costs less than 50 SD. Additionally, 25% of visitors spend less than 50 SD on transportation compared to more than 30% who spend between 50 and 100 SD.

Table 3.

Analysis of money expenditure.

The results also show that 76.3% of the visitors were college students with academic education. It appears that university learners are more interested in visiting this site. This result is similar to Enyew’s 2003; according to Enyew’s results, most visitors have a college or university education []. The results indicated that 68.4% of visitors stay at the entertainment site for about half a day, between 3–6 h. This may be a particular site for trips organized by visitors to wait half a day at this site. The results show that 92% of visitors are in family and friend groups. This is a good indication of the interest of the visitor sample in this site that it is suitable for families to enjoy different recreational activities.

However, this study sheds light on the costs and advantages of recreational trips to natural areas in the Al-Sunut Forest. The results show that travel expenses and forest sites are closely related to trips to the forest. More amenities that could help shorten travel distances and, as a result, reduce travel expenses to forests are needed if the goal is to motivate visitors to frequent natural areas for recreational purposes. For instance, to help ease traffic congestion, the existing road network to natural areas might be enhanced. Poor roads should also receive maintenance.

3.5. Estimating Different Forms of Individual Travel Cost Functions

The economic theories do not offer much guidance on selecting a suitable functional form of trip cost. As a result, the statistical method was employed to ascertain the active state of the travel cost. The Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) method was utilized with R package software to determine the relationship between variables. Several associations were examined, and a linear relationship was the best-fitting model. Using Eviews software, the relationship between the variables was determined using OLS. Although there were other associations, Nillesen et al. (2005) found that the linear relationship was the most acceptable model []; log-likelihood values, modified R-squared, and F-statistic are typically employed to evaluate various functional forms. The Test statistic of Durbin–Watson expands on the most well-known test for identifying serial autocorrelation. There was no autocorrelation in the linear-log and log-linear models in this investigation, as indicated by the Durbin–Watson value of around 2. The linear model was selected to estimate the travel function since its variables’ significance was more significant than the other models. The F-statistic was substantial in the linear model at a level of 1% []. In the linear model, the rectified R-squared statistic approaches 0.01684. It indicates that 84% of changes in the model’s dependent variable, which is the number of visits to the study site, could be accounted for by the explanatory factors of the model. Additionally, the residual of the estimated model does not appear to be autocorrelated based on the Durbin–Watson value of 0.7825. The model as a whole is significant at the level of 1%, as evidenced by the F-statistics significance at the 1% level. Using the OLS approach, the results of estimated coefficients, the significance level of variables, and the potency of explanatory factors in regression models on dependent variables are achieved.

Otherwise (Table 4 and Table 5) show a significant relationship between willingness to pay and the variables education level, family size, income, cost of the trip, and impacts at the level of certainty of 99%. Additionally, frequent variations in site visitors’ stay time occurred with a 95% certainty level.

Table 4.

The results of estimating different travel function forms.

Table 5.

Estimating travel cost functions to assess the value of a forest site for recreational purposes.

The Linear-log model is regarded as the most appropriate based on the coefficient of deamination (R2), Durbin–Watson, and log-likelihood ratio. Table 5 shows the results of the linear regression model’s analysis of the six explanatory variables, which showed that five statistically impacted the number of visitors to the forest site. Five explanatory factors, all of statistical significance, are included in the linear regression model. These variables all affect how many people visit the forest site.

4. Discussion

The investigation aimed to estimate the economic assessment of the recreational value of the Al-Sunut natural reserved forest in Khartoum, Sudan. As a result, the ITCM determines the economic importance of ecosystem goods and services according to the descriptive data on the socioeconomic characteristics of the visitors to the Al-Sunut Forest; there was slight variation in visitor gender, with a virtually equal proportion of male and female visitors. The result above is linked to a study conducted in the Munich Metropolitan Region’s Adventure Trail and World Forests, where women were slightly overrepresented. The age group between 31 and 40 was overrepresented in the “Forest Adventure Trail”, whereas the largest age group in the “World Forest” was younger, between 21 and 30 []. Based on the results of the previous research, the characteristics of visitors appear differently, with women representing the majority of visitors (57%) [].

Given that young people represent the majority of visitors, this result indicates that young people are more interested in visiting recreational sites. This finding is consistent with [], which found that most visitors to Malawi’s Lengwe National Park are from 31 to 50.

Over 75% of the visitors were undergraduate students, according to employment and education statistics, which is shown in our results. This finding was consistent with [], which indicates that people with higher levels of education were often overrepresented in forests. In the “World Forest”, the percentage of people with a higher education is more significant.

According to the results, the permanent residences of more than 35% of the participants were located 10–19 km from the forest. Thirty percent of participants live 20 to 29 miles away. With 57% of participants taking an hour or less to travel to the forest site, most visitors were lodging near the location. However, a prior survey discovered that while little less than twenty-five percent of visitors to national forests traveled more than 200 miles, nearly half of them were residents living within 50 miles of the park they visited; according to this information, a significant proportion of visitors live close to the forest [].

According to the findings, over 40% and 28% of the participants knew the recreation site for two to six and seven to eleven years, respectively. More than 92% of the respondents said they had visited the site for recreation at least once in the previous year; 33% had visited three to six times, and 21% had visited more than fifteen times. In addition, 71% of the participants reported varying numbers of excursions between their recreation plan trips and advice for recreation over the year. The differences between the planned and actual visits were clarified with a list of reasons. Recreation time constraints were the most commonly cited cause, followed by financial constraints. This indicates that the individual’s previous awareness of the location of the forest site, the level of income, and availability of leisure time influence the number of trips; in other words, the more there is prior awareness of the location of the site and the higher the level of income, the higher the number of trips to the forest site. This latter result is in line with Kassaye’s 2019 []. Recreational areas, where visitors’ monthly income is considered one of the main variables positively affecting the number of visits []. This finding is consistent with [], which found that the coefficient on the income variable showed that the number of trips could increase if the income level of visitors rose to a higher income level. In contrast, the total number of trips per person could increase if the average duration of education increased by one year.

Additionally, the results showed that visitors spend an average of 3 to 11 h per visit at the forest recreational site, with 68% spending between 3 and 6 h. Most of these visits are planned in groups of 3 to 6 and 7 to 11 individuals, with friends making up three-quarters of these groups. However, less than 60% of visitors usually prefer weekend recreation, with public holidays traveling in second (33%). About 58% of visitors say they would rather travel during the summer, while 36% say they would rather travel during the winter. Of the visitors, just 6% said they preferred visiting recreational places in the fall because the sites are undoubtedly flooded with rainfall during this time of year.

The majority of visitors are students, as evidenced by the fact that nearly all of them have a monthly income. However, over 60% of them earn less than 5000 SD. The visitors make between 5000 and 9000 SD monthly, or 29% of total income. Furthermore, rent (home, property used for business purposes) and the assistance of friends, family, and other relatives account for more than half of the respondents’ monthly income. Over 25% of the visitors’ monthly income comes from business activity. Almost 53% of the visitors said they would most likely perform unpaid work if they were not traveling.

More studies on fuel-efficient vehicles and frequent public transportation to these regions may exist. Urban gardening, urban forestry, and urban greening are all potential ways to address some urban dwellers’ needs for nature-based amenities. Though recreation experiences benefit society, it is necessary to remember when planning and building a recreation site that nature also offers other ESs that are crucial for society. The loss of other ESs may result from managing nature to the supply of a single service. To support the simultaneous provision of numerous ESs, land use planners and recreation managers must consider potential design and management strategies for nature areas.

The transportation cost to visit the recreational site had a variable coefficient of 0.005053, which, at a 1% significance level, was considered significant; it shows that when a recreational site’s distance increases, the number of visits decreases. In this study, ITCM was used to evaluate the economic worth of Al-Sunut Forest, one of the most significant recreational destinations in Khartoum State. Results showed that the trip expense was negatively linked with the number of visits, indicating that the number of visits will decrease as the travel expense increases. These findings were consistent with those of other studies, such as Chae et al. (2011) [] and Fixon and Pangapanga (2016) []. According to a 2016 study on the Lengwo Forest Park in Malawi by Fixon and Pangapanga, there is a definite association between income and the number of trips as well as an opposite relationship between the number of visits and the cost of travel for each individual every year. At a 95% confidence level, there was a significant negative connection between the number of visits and the distance traveled. Roughly half a day was spent by 38% of visitors to the park once a week, making up the majority of visitors to the Ghaleh Rudkhan forest park (55.7%) who were locals who traveled no more than 200 km. The length of stay and cost will increase with the site’s increasing distance [].

5. Conclusions

The estimated consumer surplus for each person for his visit to Al-Sunut Forest amounted to 21,500 SDG; the results also showed that travel expenses, income, distance, family size, and age of visitors are factors affecting the recreational use of the site. Most visitors were between the ages of 21 and 30, and most were students. A further finding from our study was that visitors with higher incomes were willing to take more trips. The results of this study are positive and serve as a helpful reference in formulating policies for the future management of forests for recreational purposes. The results additionally showed that forests have significant recreational value, which from this vantage point may assist the national forestry office and economic managers in ensuring the future planning and sustainable use of natural forests.

Accurate knowledge of travel expenses, including those associated with distance and travel time, and the amount of time tourists are willing to spend traveling to and staying at the recreation site, is essential for ITCM. Estimating the recreational value of the study area using the ITCM, showing that the cost of visitor travel and expenses spent within the forest site, such as the expenses of eating and drinking and others, is the estimated value to visit an entertainment site; however, the results of this study could help policymakers and managers improve the quality of Entertainment sites according to the destinations and opinions of visitors. Further studies can be conducted based on the current findings to obtain more precise strategies to enhance the value of urban recreation, improve the effectiveness of management and planning of recreation sites, and promote sustainable development in protected areas in Sudan.

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The findings of this study have significant policy implications for the economic assessment of recreation value in Sudan’s protected areas. The study illustrates the significance of using this kind of travel cost methodology for estimating the economic value of recreation to natural attractions. There are also some limitations to this study. On the one hand, the characteristics identified in this study for the recreation forest site may not be accessible to other sites. The attribute of this method must be verified or redesigned when assessing the recreational value of various natural resources in other places.

7. Recommendations

Suppose the goal is to motivate people to frequent nature areas for recreation. In that case, providing additional services that might reduce travel time and expenses to a natural area is essential. The Al-Sunut natural reserved forest is one of the distinctive sites with the potential to provide such service if authorities pay attention to the site’s resources, as there is a need for good organization and planning of the site. The site offers opportunities to practice many recreational activities such as photography, bird watching, adventure sports tourism, cultural tourism, cycling, and fishing. All these activities can be provided within the forest with good planning, management, and improved visitor services. Based on the results, it can be determined that the Al-Sunut natural reserved forest is a valuable site for visitors, and this result was based on their actual conduct. These findings can help Sudanese municipal planners, decision-makers, and the forest office.

A distinctive and attractive recreational site characterizes the Al-Sunut Forest. Therefore, it is recommended that the competent authorities pay attention to this site and provide various tourist means that have positive effects on increasing the recreational demand for local visitors, as well as it would be a destination for visitors from around the world and this will enhance the recreational value of the valuable site for the management of the Al-Sunut Forest.

8. Limitations and Future Studies

Due to the shortage of funds and the authors’ limited capabilities, the questionnaires only circulated from January to March during the winter season. We suggest that future studies conduct additional season surveys to improve the accuracy of the findings and obtain opinions for recreational during different seasons.

The study also reveals some areas that require improvements for more site views, such as (tourism, sailing sports, fishing, etc.) which can increase the recreational benefit of the forest site for visitors. The results will also inform government officials to decide about the Al-Sunut Forest and other recreational areas and consider international places for tourists.

We also advise the government to pay attention to the investment in the Al-Sunut Forest, which would lead to regular maintenance of ecosystem services, job creation, and local economic and recreational site support.

Based on the questionnaire results, we proposed developing the Al-Sunut Forest Reserve site for visitors who want to spend more than one day in the forest and facilities such as cable transportation. ITCM study in various areas with different techniques and assumptions is required to strengthen and improve the robustness to understand its potential and limitations better.

Author Contributions

Y.C. helped conceptualize the study design idea and advised in all processes. S.Y.: study design, data collection, Performed the statistical analysis, and contributed to writing (review and editing). A.E. and E.E. reviewed, edited, formal data analysis, and validated. Contributed to the collection of data and provided their intellectual insight. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Key research topics for economic and social development in Heilongjiang Province (22JYB231).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The article contains the original contributions presented in the study; the First author can be contacted for more information.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Chinese government scholarship (CSC Scholarship) and the Northeast Forestry University (NEFU) doctoral research, and we extend gratitude to the College of Economics and Management for their cooperation and support as well as to the School of International Education and Exchange Northeast Forestry University Harbin for assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Vallés-Planells, M.; Galiana, F.; Van Eetvelde, V. A classification of landscape services to support local landscape planning. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, R.; Fisher, B.; Christie, M.; Aronson, J.; Braat, L.; Gowdy, J.; Haines-Young, R.; Maltby, E.; Neuville, A.; Polasky, S. Integrating the ecological and economic dimensions in biodiversity and ecosystem service valuation. In The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Ecological and Economic Foundations; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 9–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sangha, K.K.; Le Brocque, A.; Costanza, R.; Cadet-James, Y. Ecosystems, and indigenous well-being: An integrated framework. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2015, 4, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour, M.D.; Barati, A.A.; Azadi, H.; Scheffran, J.; Shirkhani, M. Analyzing forest residents’ perception and knowledge of forest ecosystem services to guide forest management and conservation. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 146, 102866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daněk, J.; Blättler, L.; Leventon, J.; Vačkářová, D. Beyond nature conservation? Perceived benefits and role of the ecosystem services framework in protected landscape areas in the Czech Republic. Ecosyst. Serv. 2023, 59, 101504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raum, S. The ecosystem approach, ecosystem services, and established forestry policy approaches in the United Kingdom. Land Use Policy 2017, 64, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestard, A.B.; Font, A.R. Estimating the aggregate value of forest recreation in a regional context. J. For. Econ. 2010, 16, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.L.; Jones, S.K.; Johnson, J.A.; Brauman, K.A.; Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Fremier, A.; Girvetz, E.; Gordon, L.J.; Kappel, C.V.; Mandle, L. Distilling the role of ecosystem services in the Sustainable Development Goals. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 29, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, H.; Jaung, W.; Bhatta, L.; Phuntsho, S.; Sharma, S.; Paudyal, K.; Zarandian, A.; Sears, R.; Sharma, R.; Dorji, T. Approaches and Tools for Assessing Mountain Forest Ecosystem Services; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2018; Volume 235. [Google Scholar]

- Bulatovic, J.; Mladenović, A.; Rajović, G. The possibility of development of sport-recreational tourism on mountain area trešnjevik-lisa and environment. Eur. J. Econ. Stud. 2019, 8, 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Amoako-Tuffour, J.; Martínez-Espiñeira, R. Leisure and the net opportunity cost of travel time in recreation demand analysis: An application to Gros Morne National Park. J. Appl. Econ. 2012, 15, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limaei, S.M.; Ghesmati, H.; Rashidi, R.; Yamini, N. Economic evaluation of natural forest park using the travel cost method (case study; Masouleh forest park, north of Iran). J. For. Sci. 2014, 60, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sri Lanka, U.-R. Sri Lanka’s Forest Reference Level Submission to the UNFCCC; UN-REDD: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Daur, N.; Adam, Y.O.; Pretzsch, J. A historical political ecology of forest access and use in Sudan: Implications for sustainable rural livelihoods. Land Use Policy 2016, 58, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paracchini, M.L.; Zulian, G.; Kopperoinen, L.; Maes, J.; Schägner, J.P.; Termansen, M.; Zandersen, M.; Perez-Soba, M.; Scholefield, P.A.; Bidoglio, G. Mapping cultural ecosystem services: A framework to assess the potential for outdoor recreation across the EU. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 45, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandersen, M.; Tol, R.S. A meta-analysis of forest recreation values in Europe. J. For. Econ. 2009, 15, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassaye, T.A. Determinant factors affecting the number of visitors in recreational parks in Ethiopia: The case of Addis Ababa recreational parks. World Sci. News 2019, 118, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Eltayeb, H.; Idris, E.; Adam, A.; Ezaldeen, T.; Hamed, D. A forest in a city Biodiversity at Sunut forest, Khartoum, Sudan. Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci. B Zool. 2012, 4, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, N.E.A. Appraisal of Forest Changes Using Change Detection Analysis in Alsunt Forest Khartoum State of Sudan. Master’s Thesis, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Skudai, Malaysia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Borzykowski, N.; Baranzini, A.; Maradan, D. A travel cost assessment of the demand for recreation in Swiss forests. Rev. Agric. Food Environ. Stud. 2017, 98, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornatowska, B.; Sienkiewicz, J. Forest ecosystem services–assessment methods. Folia For. Polonica. Ser. A For. 2018, 60, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, R.S.; Wilson, M.A.; Boumans, R.M. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 41, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, J.; Smith, L.; Case, J.; Linthurst, R. A review of the elements of human well-being with an emphasis on the contribution of ecosystem services. Ambio 2012, 41, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Tahir, B.A. Climate Change Adaptation through Sustainable Forest Management in Sudan: Needs to Qualify Agroforestry Application. Sudan Acad. Sci. J. 2015, 11, 162–185. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, S.; Baral, H.; Nitschke, C.R. Identification, prioritization and mapping of ecosystem services in the Panchase Mountain Ecological Region of Western Nepal. Forests 2018, 9, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiszewski, I.; Costanza, R.; Dorji, L.; Thoennes, P.; Tshering, K. An initial estimate of the value of ecosystem services in Bhutan. Ecosyst. Serv. 2013, 3, e11–e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, R.R.; Choden, K.; Dorji, T.; Dukpa, D.; Phuntsho, S.; Rai, P.B.; Wangchuk, J.; Baral, H. Bhutan’s forests through the framework of ecosystem services: Rapid assessment in three forest types. Forests 2018, 9, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S. Travel Cost Method for Environmental Valuation; Dissemination Paper; Center of Excellence in Environmental Economics, Madras School of Economics: Chennai, India, 2013; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Ortaçeşme, V.; Özkan, B.; Karagüzel, O. An estimation of the recreational use value of Kursunlu Waterfall Nature Park by the individual travel cost method. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2002, 26, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Tisdell, C.; Wen, J. Foreign tourism as an element in PR China’s economic development strategy. Tour. Manag. 1991, 12, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayaga, P.; Rolfe, J.; Sinden, J. A travel cost analysis of the value of special events: Gemfest in Central Queensland. Tour. Econ. 2006, 12, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, A. Economic valuation of wetlands: An important component of wetland management strategies at the river basin scale. In The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2003; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.; Kumar, P. Valuation of the ecosystem services: A psycho-cultural perspective. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 808–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, D.; Singh, S.; Dhameliya, J. Assessing the value of our forests: Quantification and valuation of revegetation efforts. In Proceedings of the Paper Submitted for the Fourth Biennial Conference of the Indian Society for Ecological Economics (INSEE), Mumbai, Bali, Indonesia, 19–23 June 2006; pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- D’amato, D.; Rekola, M.; Li, N.; Toppinen, A. Monetary valuation of forest ecosystem services in China: A literature review and identification of future research needs. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 121, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, W.H.; Elagib, N.A.; Gaese, H.; Heinrich, J. Rainfall conditions and rainwater harvesting potential in the urban area of Khartoum. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 91, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.M.; Sevinc, H. Adaptation of climate-responsive building design strategies and resilience to climate change in the hot/arid region of Khartoum, Sudan. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 47, 101429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M.I.; Elagib, N.A.; Horn, F.; Saad, S.A. Lessons learned from Khartoum flash flood impacts: An integrated assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 601, 1031–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, N.A.; Madsen, H.; Ahmed, A.A.A. Types of trematodes infecting freshwater snails found in irrigation canals in the East Nile locality, Khartoum, Sudan. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2016, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, O.; Idris, E. A note on the bird diversity at two sites in Khartoum, Sudan. Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci. B Zool. 2013, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-Y.; Chen, P.-Z.; Hsieh, C.-M. Assessing the recreational value of a national forest park from ecotourists’ perspective in Taiwan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawacki, W.T.; Marsinko, A.; Bowker, J.M. A travel cost analysis of nonconsumptive wildlife-associated recreation in the United States. For. Sci. 2000, 46, 496–506. [Google Scholar]

- Khoshakhlagh, R.; Safaeifard, S.V.; Sharifi, S.N.M. Estimating recreation demand function by using zero truncated Poisson distribution: A case study of Tehran Darband site (Iran). J. Empir. Econ. 2013, 1, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, R.K.; Seidl, A.F.; Moraes, A.S. Value of recreational fishing in the Brazilian Pantanal: A travel cost analysis using count data models. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 42, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, S.; Mohammadi Limaei, S.; Amiri, N. An economic evaluation of a forest park using the individual travel cost method (a case study of Ghaleh Rudkhan forest park in northern Iran). Environ. Socio-Econ. Stud. 2018, 6, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, G.R. The travel cost model. In A Primer on Nonmarket Valuation; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 269–329. [Google Scholar]

- Pirikiya, M.; Amirnejad, H.; Oladi, J.; Solout, K.A. Determining the recreational value of forest park by travel cost method and defining its effective factors. J. For. Sci. 2016, 62, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wubalem, A.; Reynolds, T.W.; Wodaju, A. Estimating the recreational use value of Tis-Abay Waterfall in the upstream of the Blue Nile River, North-West Ethiopia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wubalem, A.; Woldeamanuel, T.; Nigussie, Z. Economic Valuation of Lake Tana: A Recreational Use Value Estimation through the Travel Cost Method. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fixon, W.; Pangapanga, P. Economic valuation of recreation at Lengwe National Park in Malawi. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2016, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, S. Exchange rate reform in Sudan. In Policy Brief-SDN-20260; Internatioal Growth Center: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yimer, E.; Enyew, M. Parasites of fish at Lake Tana, Ethiopia. SINET Ethiop. J. Sci. 2003, 26, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nillesen, E.; Wesseler, J.; Cook, A. Estimating the recreational-use value for hiking in Bellenden Ker National Park, Australia. Environ. Manag. 2005, 36, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghshenas, H.; Ghanbari Malidarreh, A. Response of yield and yield components of released rice cultivars from 1990-2010 to nitrogen rates. Cent. Asian J. Plant Sci. Innov. 2021, 1, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, D.-R.; Wattage, P.; Pascoe, S. Recreational benefits from a marine protected area: A travel cost analysis of Lundy. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).