Exploring the Role of Shared Leadership on Job Performance in IT Industries: Testing the Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

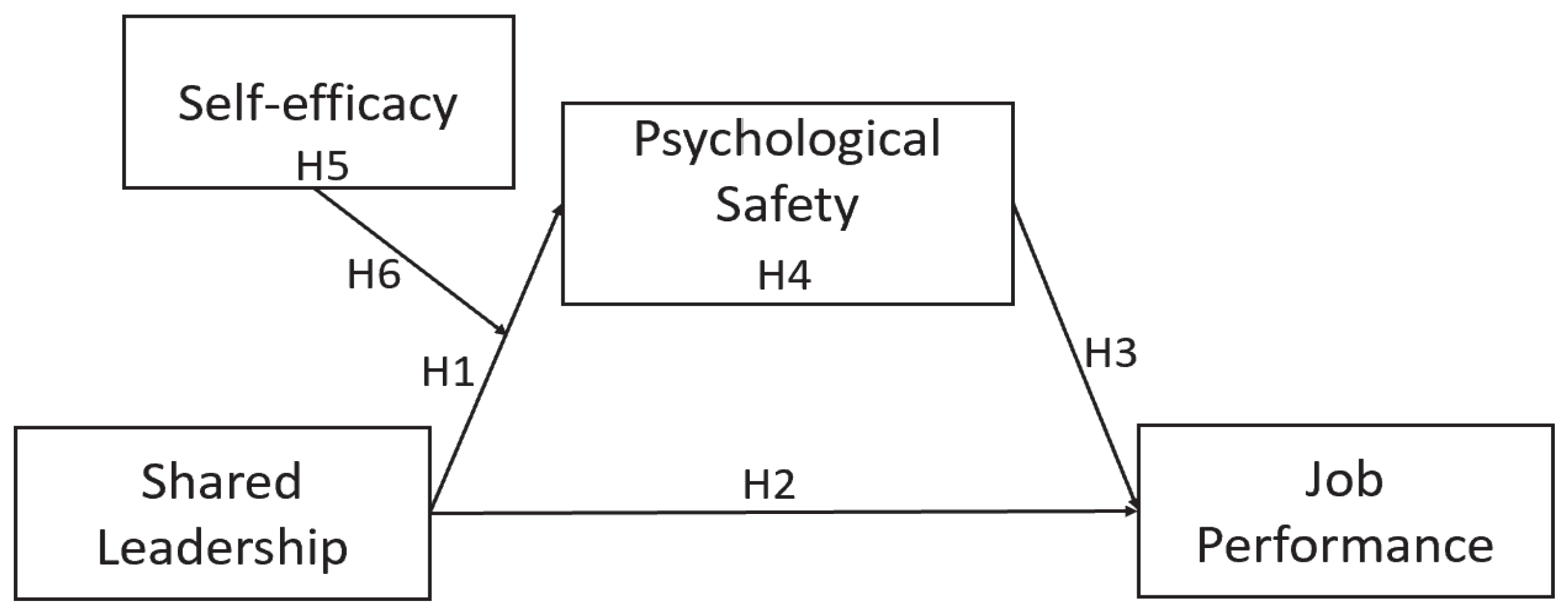

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Shared Leadership

2.2. Self-Efficacy

2.3. Psychological Safety

2.4. Job Performance

2.5. Shared Leadership and Psychological Safety

2.6. Shared Leadership and Job Performance

2.7. Psychological Safety and Job Performance

2.8. The Mediating Effect of Psychological Safety

2.9. The Moderated Mediation Effects of Self-Efficacy

3. Methods

3.1. Respondents and Procedures

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor and Reliability Analyses

4.2. Reliability Analysis

4.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

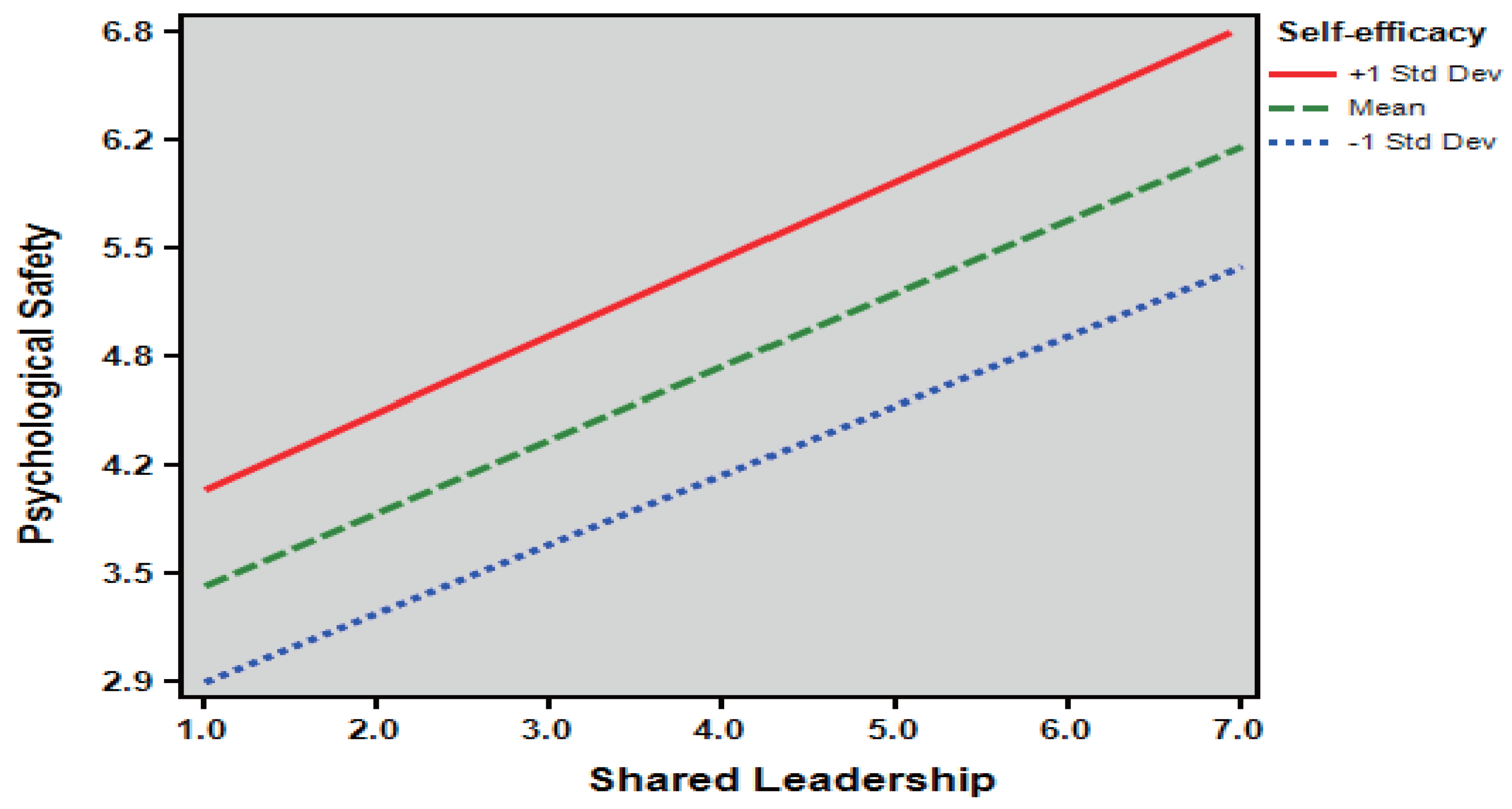

4.5. Moderating Role of Tacit Self-Efficacy

4.6. Moderated Mediation Effect of Tacit Self-Efficacy

5. Conclusions

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implication

5.4. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, J.X.; Wang, D.X.; Peng, H. The Influence of Employees’ Work Engagement on Job Performance in the Context of the Digital Economy: The Mediating Role of Psychological Capital. J. Heihe Univ. 2023, 14, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, M.; Lee, H.S. The Effect of Shared Leadership on Organizational Effectiveness: Mediating of Psychological Empowerment. Korean Acad. Assoc. Bus. Adm. 2020, 33, 2257–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, D.V.; Gronn, P.; Salas, E. Leadership capacity in teams. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 857–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, J.; Dulebohn, J. Shared leadership in enterprise resource planning and human resource management system implementation. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2013, 23, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, J. Transformational leadership and gatekeeping leadership: The roles of norm for maintaining consensus and shared leadership in team performance. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2012, 29, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, J.E.; Gosselin, J.T. Self-Efficacy; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 10, pp. 198–224. [Google Scholar]

- Hamel, G.; Breen, B. Building an innovation democracy: WL Gore. In The Future of Management; Path Institute: Fontana, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Avery, G.C.; Bergsteiner, H. Honeybees & Locusts: The Business Case for Sustainable Leadership; Allen & Unwin: Crows Nest, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Krittayaruangroj, K.; Iamsawan, N. Sustainable Leadership practices and competencies of SMEs for sustainability and resilience: A community-based social enterprise study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shondrick, S.J.; Dinh, J.E.; Lord, R.G. Developments in implicit leadership theory and cognitive science: Applications to improving measurement and understanding alternatives to hierarchical leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 959–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunjak, A.; Bruch, H.; Černe, M. Context is key: The joint roles of transformational and shared leadership and management innovation in predicting employee IT innovation adoption. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 66, 102516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, T.L.; Vessey, W.B.; Schuelke, M.J.; Ruark, G.A.; Mumford, M.D. A framework for understanding collective leadership: The selective utilization of leader and team expertise within networks. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 933–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.M. Leadership; Open Road Media: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Youmin, X.; Hongwen, X.; Hongtao, W. HeXie Management Theory and Its New Development in the Principles. Chin. J. Manag. 2005, 2, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Waldman, D.A.; Zhang, Z. A meta-analysis of shared leadership and team effectiveness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, B.; Wang, J. The role of growth mindset, self-efficacy and intrinsic value in self-regulated learning and English language learning achievements. Lang. Teach. Res. 2023, 27, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhigang, S.; Fengmei, R. Shared Leadership in Innovation Teams: Connotation Expansion and Scale Development. J. Tianjin Univ. 2023, 25, 108–117. [Google Scholar]

- Yixin, M.; Yuexian, T. Research status of shared leadership theory in nursing management. Chin.-Evid.-Based Nurs. 2023, 9, 1023–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Ro, Y.S. A Study on The Impacts of Shared Leadership on Organizational Effectiveness with the Mediating Effect of Organizational Trust. Hankuk Univ. Foreign Stud. Inst. Gov. 2022, 39, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sangeetha, P.; Kumaran, S. Impact of shared leadership on cross functional team effectiveness and performance with respect to manufacturing companies. J. Manag. Res. 2018, 18, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Son, E.L.; Song, J.S. The Study on the Relationship of Between Ethical Leadership, Psychological Empowerment and Organizational Committment. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Res. 2012, 19, 237–252. [Google Scholar]

- Peracek, T.; Kassaj, M. The influence of jurisprudence on the formation of relations between the manager and the limited liability company. Jurid. Trib. 2023, 13, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Hoch, J.E. Shared leadership and innovation: The role of vertical leadership and employee integrity. J. Bus. Psychol. 2013, 28, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Cha, M. The study on the influence of the shared leadership on the organizational performance: Mediating effects of the positive psychological capital and the knowledge sharing. Korea Leadersh. Rev. 2018, 9, 97–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, J.H.; Zhang, Y.L. How shared leadership affects team performance: Examining sequential mediation model using MASEM. J. Manag. Psychol. 2022, 37, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Liu, X.J.; Fu, F.L. Research on the Relationship Between Shared Leadership and Employee Engagement. J. Hunan Univ. Financ. Econ. 2012, 37, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ertürk, K.A.; Ertürk, K.A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: Social Foundations of Thought and Action; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Career development from a social cognitive perspective. Career Choice Dev. 1996, 3, 373–421. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. The nature and structure of self-efficacy. In Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; WH Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 37–78. [Google Scholar]

- Heslin, P.A.; Klehe, U.; Rogelberg, S. Encyclopedia of industrial/organizational Psychology; Rogelberg, S.G., Ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 705–708. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, H.; Xu, H.; Dupre, M.E. Self-efficacy. In Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 4410–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselin, J.T.; Maddux, J.E. Self-efficacy. In Handbook of Self and Identity; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 218–238. [Google Scholar]

- Yan-Hua, H.U.; Ying, J.; Xue-Mei, C.; Education, S.O. The Relationship between College Students’ Self-efficacy in Career Decision-making and Employability: The Intermediary Role of Career Planning. Theory Pract. Educ. 2019, 39, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.W.; Cho, Y.H. Mediation and moderation effects of self-efficacy between career stress and college adjustment among freshmen. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2011, 18, 197–218. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Kim, B. The effect of anxiety and career decision-making self-efficacy on career decision level. J. Career Educ. Res. 2007, 20, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, R.; He, Y.; Gan, C. Research on the Impact of Authentic Leadership on Employees’ Happiness: Based on the Chained Mediational Role between Self-efficacy and the Authenticity of Work and Family. J. China Univ. Labor Relat. 2021, 32, 283–288. [Google Scholar]

- Samancioglu, M.; Baglibel, M.; Erwin, B.J. Effects of Distributed Leadership on Teachers’ Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment and Organizational Citizenship. Pedagog. Res. 2020, 5, em0052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, S.J.; Rothbard, N.P.; Piderit, S.K.; Dutton, J.E. Out on a limb: The role of context and impression management in selling gender-equity issues. Adm. Sci. Q. 1998, 43, 23–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessel, M.; Kratzer, J.; Schultz, C. Psychological Safety, Knowledge Sharing, and Creative Performance in Healthcare Teams. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2012, 21, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, J.; Baek, S. The Impact of Leader-member Exchange (LMX) on EmployeesTaking Charge Behavior and Voice Behavior: Focusing on the Mediating Role of Psychological safety. Korean Manag. Rev. 2013, 42, 613–643. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Wei, K.K.; Chen, H. Exploring the role of psychological safety in promoting the intention to continue sharing knowledge in virtual communities. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2010, 30, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Power and Exchange in Social Life; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Pu, K. Correlation Research of Psychological Security and Happiness Subjectivity of College Students from the Cultural Perspective of “Slow Employment”. Heilong Jiang Sci. 2023, 14, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.J. A Study About the Effect of Outplacement Support Program for Discharged Soldiers on Job-Seeking Efficacy and Psychological Stability-with Focus on the Mediating Effect of Learning Commitment and Program Satisfaction. J. Vocat. Educ. Res. 2010, 29, 265–289. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S.J. The Relationships among TVET Service Quality, Psychological stability, Informal Networks and Employability of the Middle-aged Unemployed Vocational Trainees. J. Vocat. Educ. Res. 2015, 24, 115–139. [Google Scholar]

- Borman, W. Expanding the Criterion Domain to Include Elements of Contextual Performance. In Personnel Selection in Organizations; Psychology Faculty Publications: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, D.; Avolio, B. Opening the Black Box: An Experimental Investigation of the Mediating Effects of Trust and Value Congruence on Transformational and Transactional Leadership. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 949–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P. Does Mentorship among Social Workers Make a Difference? An Empirical Investigation of Career Outcomes. Soc. Work. 1994, 39, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, S.H. A study on relationship among self-leadership, teamwork, self-efficacy, job satisfaction, organizational commitment and job performance of hotel staffs. J. Hosp. Tour. Stud. 2010, 37, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.; Peterson, R. Antecedents and Consequences of Salesperson Job Satisfaction: Meta-Analysis and Assessment of Causal Effects. J. Mark. Res. 1993, 30, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.C.; Wu, J.Q.; Chen, D.J. The Impact of Technostress on Teachers’ Work Performance under the Digital Transformation: Based on the Analysis of Mediating and Moderating Effects of Teaching Innovation Behavior and Different Mindsets. Mod. Educ. Technol. 2023, 33, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, H.; Shim, D.S.; Kim, M.J. The effects of leaders’ ethical leadership on followers’ job performance, organizational commitment and organization citizenship behaviors: The mediating effect of organization-based self-esteem and the moderating effect of corporate ethical values. Korean J. Bus. Adm. 2013, 26, 801–827. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H. A study on the effects of organizational justice in Local governments performance-oriented human resource management on civil servants job satisfaction, organizational commitment and job performance: Focused on Busan. Korean J. Local Gov. Stud. 2015, 19, 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. Study on the Effects of Work—Family Conflict and Family Support on Job Performance of Resident Village Cadres. J. Guizhou Norm. Univ. Sci. 2018, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E. Energize Your Workplace: How to Create and Sustain High-Quality Connections at Work; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, H.W.; Kim, S.U.; Kim, O.L.S.L.J.E.M. The School Characteristics with High Psychological Safety: Focusing on the Principal Leadership. J. Korean Teach. Educ. 2021, 38, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y.B.; Lee, N.Y.; Park, K.H. The Effect of Inclusive Leadership on Organizational Commitment: The Mediating effect of Psychological safety. J. Soc. Value Enterp. 2018, 10, 231–259. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A.; Gelbard, R.; Reiter-Palmon, R. Leadership, Creative Problem-Solving Capacity, and Creative Performance: The Importance of Knowledge Sharing. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 52, 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.; Parker, S.; Mason, C. Leader Vision and the Development of Adaptive and Proactive Performance: A Longitudinal Study. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, M.; Ahmad, D.S.; Poespowidjojo, D. The Role of Psychological Safety and Psychological Empowerment on Intrapreneurial Behavior towards Successful Individual Performance: A Conceptual Framework. Sains Humanika 2018, 10, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological Safety, Trust, and Learning in Organizations: A Group-level Lens. In Trust and Distrust in Organizations: Dilemmas and Approaches; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A.; Lei, Z. Psychological Safety: The History, Renaissance, and Future of an Interpersonal Construct. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detert, J.; Treviño, L. Speaking Up to Higher-Ups: How Supervisors and Skip-Level Leaders Influence Employee Voice. Organ. Sci. 2010, 21, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bartol, K. Linking Empowering Leadership and Employee Creativity: The Influence of Psychological Empowerment, Intrinsic Motivation, and Creative Process Engagement. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Erdogan, B.; Jiang, K.; Bauer, T.; Liu, S. Leader Humility and Team Creativity: The Role of Team Information Sharing, Psychological Safety, and Power Distance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 103, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, M.; Frese, M. Innovation is Not Enough: Climates for Initiative and Psychological Safety, Process Innovations, and Firm Performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.; Schaubroeck, J. Leader Personality Traits and Employee Voice Behavior: Mediating Roles of Ethical Leadership and Work Group Psychological Safety. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1275–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, J.; Mayo, M. Shared Leadership in Work Teams: A Social Network Approach; Working paper; Instituto de Empresa: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Han, J.; Fisher, C.; Pan, Y. Learning to Share: Exploring Temporality in Shared Leadership and Team Learning. Small Group Res. 2017, 48, 104649641769002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, J.D.; Neck, C.P.; Manz, C.C. Self-leadership and superleadership. In Shared Leadership: Reframing the Hows and Whys of Leadership; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Liu, M. Shared leadership, psychological security and voice behavior. Indus. Eng. Manag. 2018, 23, 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Yaping, M.; Liang, L.; Guyang, T.; Xue, Z.; Yezhuang, T. Research on the Shared Roles and Shared Timings of Shared Leadership in the Context of Environmental Uncertainty Based on Case Study. Chin. J. Manag. 2023, 20, 1263–1274. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, J.H.; Zhang, Y.L. How Shared Leadership Affects Team Performance: A Mediation Analysis with MASEM. Q. J. Manag. 2022, 7, 26–48+130–131. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, E.J.; Harrington, K.M.; Clark, S.L.; Miller, M.W. Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2013, 73, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derahim, N.; Arifin, K.; Wan Isa, W.M.Z.; Khairil, M.; Mahfudz, M.; Ciyo, M.B.; Ali, M.N.; Lampe, I.; Samad, M.A. Organizational safety climate factor model in the urban rail transport industry through CFA analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Farh, C.; Farh, J.L. Psychological Antecedents of Promotive and Prohibitive Voice: A Two-Wave Examination. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G. Socialization Tactics, Self-Efficacy, and Newcomers’ Adjustments to Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 1986, 29, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.; Boles, J. The effects of perceived co-worker involvement and supervisor support on service provider role stress, performance and job satisfaction. J. Retail. 1996, 72, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Schunk, D. Cultivating competence, self-efficacy, and intrinsic interest through proximal self-motivation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 41, 586–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S. The criteria for selecting appropriate fit indices in structural equation modeling and their rationales. Korean J. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 19, 161–177. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, X. Structural Equation Modeling: Applications Using Mplus; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.G.; Lee, H.B. Structural Relationships among Customer Loyalty, Satisfaction and Trust of Internet Banking. J. Korean Data Anal. Soc. 2012, 14, 1139–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Zhou, M. Analysis of farmers’ land transfer willingness and satisfaction based on SPSS analysis of computer software. Clust. Comput. 2019, 22, 9123–9131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. An overview of psychological measurement. In Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders: A Handbook; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1978; pp. 97–146. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D. Alternatives to P value: Confidence interval and effect size. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2016, 69, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.G.; Wang, C.H.; Jiang, M.Y.; Yang, H.L. A Study on the Relationship between Cyberloafing of Employees and Job Performance: The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction and the Moderating Role of Organizational Justice. J. Zhengzhou Univ. Aeronaut. 2023, 41, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Grille, A.; Kauffeld, S. Development and Preliminary Validation of the Shared Professional Leadership Inventory for Teams (SPLIT). Psychology 2015, 06, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenhead, J.; Franco, L.; Grint, K.; Friedland, B. Complexity theory and leadership practice: A review, a critique, and some recommendations. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 101304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonnaya, C.; Valizade, D. High performance work practices, employee outcomes and organizational performance: A 2-1-2 multilevel mediation analysis. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 29, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherf, E.; Parke, M.; Isaakyan, S. Distinguishing Voice and Silence at Work: Unique Relationships with Perceived Impact, Psychological Safety, and Burnout. Acad. Manag. J. 2020, 64, 114–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Wang, H.; Boekhorst, J.A. A moderated mediation examination of shared leadership and team creativity: A social information processing perspective. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2023, 40, 295–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.D.; Jin, Y.G.; Qian, Z.C. The Effect of Shared Leadership on Employee Adaptive Performance: Based on Self-Determination Theory. Sci. Sci. Manag. 2019, 40, 140–154. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.; Kim, S.; Yun, S. Supervisor knowledge sharing and creative behavior: The roles of employees’ self-efficacy and work–family conflict. J. Manag. Organ. 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Liu, M.; Xu, M. The Effectiveness of Shared Leadership Competency: Roles of Shared Leadership And Team Participatory Safety. Chin. J. Manag. 2020, 17, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Ding, R.; Wang, N. Emergence of Shared Leadership Behaviors and Effect on Innovation Performance in R&D Team: Based on the Influence of Vertical Leadership. J. Manag. Sci. 2018, 31, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Ma, L. The influence of shared leadership on employee proactive innovation behavior. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Management Science and Innovative Education, Sanya, China, 15–16 October 2016; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, B. The Mediation Effect of Knowledge Sharing and Organizational Identification between Collective Leadership and Work Engagement. J. Contents Ind. 2023, 5, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.S. The effect of shared leadership on organizational trust, knowledge sharing and innovative behavior. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2019, 19, 485–500. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Oh, S. The Effect of Shared Leadership on Knowledge Hiding: Mediating Role of Knowledge Sharing and Organizational Silence. Korean Acad. Assoc. Bus. Adm. 2020, 33, 1193–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, Q.; Ling, L.; Yan, Y. Team Leadership, Trust, and Team Psychological Safety: A Mediation Analysis. J. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 35, 208. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.M.; Liu, Z. Research on the Influence of Shared Leadership on Team Creativity. Soft Sci. 2019, 33, 114–118+140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suk, J.H. The Mediating Effect of Academic Resilience on the Relationship between Shared Leadership, Self-efficacy for Group work, and Team Efficacy in University Team Based Learning. J. Wellness 2023, 31, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.; Qing, C.; Jin, S. Ethical Leadership and Innovative Behavior: Mediating Role of Voice Behavior and Moderated Mediation Role of Psychological Safety. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jin, X. Exploring the relationship between Transformational Leadership and Innovative Behavior: Testing the Moderated Mediation Effect of Psychological Safety. J. Ind. Converg. 2023, 21, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, D.M.; Fedor, D.B.; Caldwell, S.; Liu, Y. The effects of transformational and change leadership on employees’ commitment to a change: A multilevel study. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, A.; Clarke, N.; Higgs, M. Shared leadership in commercial organizations: A systematic review of definitions, theoretical frameworks and organizational outcomes. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binaku, M. Violations of the Rigts of Employees in Public and Private Sector in Kosova. Perspect. Law Public Adm. 2021, 10, 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Marica, M.E. Considerations on Employee Sharing in the Context of GDPR. Perspect. Law Public Adm. 2021, 10, 241–246. [Google Scholar]

| Number of Respondents | Percentage of Respondents | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total respondents | 320 | 100 | |

| Gender | Male | 249 | 77.80% |

| Female | 71 | 22.20% | |

| Age | 20–29 | 234 | 73.10% |

| 30–39 | 33 | 10.30% | |

| 40–49 | 26 | 8.10% | |

| 50 or more | 27 | 8.50% | |

| Education | Graduates from junior college | 226 | 70.70% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 67 | 20.90% | |

| Master’s degree | 19 | 5.90% | |

| Doctoral degree or higher | 8 | 2.50% | |

| Service Year | 1 year or less | 166 | 51.90% |

| 1–3 years | 58 | 18.10% | |

| 4–6 years | 19 | 5.90% | |

| 7–9 years | 13 | 4.10% | |

| 10 years or more | 64 | 20% | |

| Position | General staff | 96 | 30% |

| Team leaders | 16 | 5% | |

| Section chief | 11 | 3.40% | |

| Division chief | 6 | 1.90% | |

| other kinds | 191 | 59.70% |

| Variables | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Standardized Regression Weights | AVE | C.R | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shared Leadership (SL) | SL25 | 1 | 0.91 | 0.848 | 0.99 | |||

| SL24 | 1.04 | 0.031 | 33.57 | *** | 0.924 | |||

| SL23 | 1.03 | 0.03 | 34.428 | *** | 0.929 | |||

| SL22 | 1.06 | 0.03 | 35.628 | *** | 0.937 | |||

| SL21 | 1.062 | 0.03 | 34.969 | *** | 0.933 | |||

| SL20 | 1.038 | 0.032 | 32.342 | *** | 0.916 | |||

| SL19 | 1.027 | 0.031 | 32.882 | *** | 0.919 | |||

| SL18 | 1.04 | 0.029 | 36.189 | *** | 0.94 | |||

| SL17 | 1.031 | 0.042 | 24.375 | *** | 0.838 | |||

| SL16 | 1.043 | 0.036 | 28.583 | *** | 0.885 | |||

| SL15 | 1.032 | 0.031 | 33.64 | *** | 0.924 | |||

| SL14 | 1.019 | 0.033 | 31.105 | *** | 0.906 | |||

| SL13 | 1.059 | 0.032 | 33.512 | *** | 0.924 | |||

| SL12 | 1.062 | 0.031 | 34.367 | *** | 0.929 | |||

| SL11 | 1.068 | 0.03 | 35.145 | *** | 0.934 | |||

| SL10 | 1.036 | 0.027 | 38.743 | *** | 0.953 | |||

| SL9 | 1.027 | 0.029 | 35.845 | *** | 0.938 | |||

| SL8 | 1.029 | 0.03 | 33.754 | *** | 0.925 | |||

| SL7 | 1.039 | 0.028 | 37.172 | *** | 0.945 | |||

| SL6 | 1.055 | 0.029 | 36.442 | *** | 0.941 | |||

| SL5 | 1.068 | 0.029 | 36.509 | *** | 0.942 | |||

| SL4 | 1.036 | 0.03 | 35.031 | *** | 0.933 | |||

| SL3 | 1.07 | 0.037 | 28.997 | *** | 0.888 | |||

| SL2 | 1.016 | 0.034 | 29.811 | *** | 0.896 | |||

| SL1 | 1.047 | 0.034 | 31.231 | *** | 0.907 | |||

| Self-efficacy (SE) | SE1 | 1 | 0.875 | 0.754 | 0.943 | |||

| SE2 | 1.03 | 0.034 | 29.953 | *** | 0.899 | |||

| SE3 | 0.997 | 0.053 | 18.78 | *** | 0.751 | |||

| SE4 | 1.032 | 0.04 | 26.116 | *** | 0.862 | |||

| SE5 | 1.045 | 0.043 | 24.279 | *** | 0.84 | |||

| SE6 | 1.019 | 0.033 | 30.489 | *** | 0.904 | |||

| SE7 | 1.051 | 0.031 | 34.117 | *** | 0.929 | |||

| SE8 | 1.06 | 0.038 | 27.795 | *** | 0.879 | |||

| Psychological safety (PS) | PS1 | 1 | 0.917 | 0.774 | 0.918 | |||

| PS2 | 1.066 | 0.03 | 35.403 | *** | 0.935 | |||

| PS3 | 1.106 | 0.03 | 37.16 | *** | 0.945 | |||

| PS4 | 1.03 | 0.037 | 27.897 | *** | 0.879 | |||

| PS5 | 0.917 | 0.056 | 16.437 | *** | 0.7 | |||

| Job Performance (JP) | JP1 | 1 | 0.88 | 0.815 | 0.959 | |||

| JP2 | 1.06 | 0.038 | 27.993 | *** | 0.881 | |||

| JP3 | 1.038 | 0.033 | 31.449 | *** | 0.911 | |||

| JP4 | 1.023 | 0.032 | 31.521 | *** | 0.911 | |||

| JP5 | 1.038 | 0.033 | 31.466 | *** | 0.911 | |||

| JP6 | 1.031 | 0.028 | 36.378 | *** | 0.942 | |||

| JP7 | 1.024 | 0.036 | 28.223 | *** | 0.883 | |||

| Model Fit Index | 3153.684 (0.000), 3.777, GFI = 0.706, RMR = 0.518, | |||||||

| RMSEA = 0.093, IFI = 0.923, CFI = 0.923, TLI = 0.908, NFI = 0.898, | ||||||||

| AGFI = 0.636, AIC = 3553.684, PGFI = 0.570, PNFI = 0.758 | ||||||||

| Variables | Item | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Shared Leadership (SL) | 1. Members work together to develop a plan for accomplishing the work. | 0.995 |

| 2. Members work together to allocate the required resources based on work priorities. | ||

| 3. Members work together to set goals. | ||

| 4. Members work together to coordinate efforts to ensure a smooth flow of business. | ||

| 5. Members work together to decide how to get the job done. | ||

| 6. Members provided useful comments on the overall workplan. | ||

| 7. Members work together to determine the best response to problems as they arise. | ||

| 8. The members quickly came together to analyze the problems faced. | ||

| 9. Members utilize the expertise of the entire team to solve problems. | ||

| 10. Members work together to explore alternatives to issues affecting job performance. | ||

| 11. Members work together to preempt problems before they occur. | ||

| 12. Members work together to develop solutions to problems. | ||

| 13. Members work together to solve problems as soon as they arise. | ||

| 14. Providing support to team members who need help. | ||

| 15. Showing patience toward other team members. | ||

| 16. Encouraging other team members when they’re upset. | ||

| 17. Listening to complaints and problems of team members. | ||

| 18. Members work together to create an atmosphere of mutual solidarity. | ||

| 19. Members treat each other with courtesy. | ||

| 20. Members share work-related advice. | ||

| 21. Members work together to help develop each other’s skills. | ||

| 22. Learning skills from all other team members. | ||

| 23. Being positive role models to new members of the team. | ||

| 24. Guidance among members on how underperforming members should improve. | ||

| 25. Helping out when a team member is learning a new skill. | ||

| Self-efficacy (SE) | 1. My new job is well within the scope of my abilities. | 0.971 |

| 2. I do not anticipate any problems in adjusting to work in this organization. | ||

| 3. I feel I am overqualified for the job I will be doing. | ||

| 4. I have all the technical knowledge I need to deal with my new job, all I need now is practical experience. | ||

| 5. I feel confident that my skills and abilities equal or exceed those of my future colleagues. | ||

| 6. My past experiences and accomplishments increase my confidence that I will be able to perform successfully in this organization. | ||

| 7. I could have handled a more challenging job than the one I will be doing. | ||

| 8. Professionally speaking, my new job exactly satisfies my expectations of myself. | ||

| Psychological Safety (PS) | 1. In my work unit, I can express my true feelings regarding my job. | 0.959 |

| 2. In my work unit, I can freely express my thoughts. | ||

| 3. In my work unit, expressing I true feelings is welcomed. | ||

| 4. Nobody in my unit will pick on me even if I have different opinions. | ||

| 5. I’m worried that expressing true thoughts in my workplace would do harm to myself. | ||

| Job Performance (JB) | 1. I average higher sales per check than most. | 0.978 |

| 2. I am in the top 10% of the servers here. | ||

| 3. I manage my work time better than most. | ||

| 4. I know more about the menu items. | ||

| 5. I know what my customers expect. | ||

| 6. I am good at my job. | ||

| 7. I get better tips than most of the others. |

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Shared Leadership | Self-Efficacy | Psychological Safety | Job Performance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shared Leadership | 5.7214 | 1.28077 | - | |||

| Self-efficacy | 5.6227 | 1.2525 | 0.899 *** | - | ||

| Psychological safety | 5.5669 | 1.30561 | 0.892 *** | 0.904 *** | - | |

| Job Performance | 5.6192 | 1.25668 | 0.879 *** | 0.936 *** | 0.917 *** | - |

| Path | Estimate | S.E. | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shared Leadership | → | Psychological Safety | 0.909 | 0.025 | 35.225 | 0 | 0.8587 | 0.9603 |

| Shared Leadership | → | Job Performance | 0.862 | 0.026 | 32.887 | 0 | 0.8109 | 0.9142 |

| Psychological Safety | → | Job Performance | 0.625 | 0.044 | 13.929 | 0 | 0.5375 | 0.7143 |

| Total effect of X on Y | ||||||||

| Shared Leadership → Psychological Safety → Job Performance | 0.862 | 0.026 | 32.887 | 0 | 0.8109 | 0.9142 | ||

| Direct effect of X on Y | ||||||||

| Shared Leadership → Job Performance | 0.293 | 0.045 | 6.4024 | 0 | 0.2032 | 0.3834 | ||

| Indirect effect(s) of X on Y | ||||||||

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |||||

| Shared Leadership → Psychological Safety → Job Performance | 0.569 | 0.059 | 0.447 | 0.682 | ||||

| Psychological Safety | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

| VIF | |||||||

| Shared leadership (A) | 0.892 *** | 35.226 | 0.414 *** | 8.351 | 0.332 *** | 4.851 | 1 |

| Self-efficacy (B) | 0.532 *** | 10.735 | 0.432 *** | 5.645 | 5.206 | ||

| Interaction (A × B) | 0.181 | 1.716 | 23.716 | ||||

| (Adjusted ) | 0.796 | 0.85 | 0.852 | ||||

| (ΔAdjusted ) | 0.796 | 0.054 | 0.001 | ||||

| F | 1240.865 *** | 900.944 *** | 605.292 *** | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Job Satisfaction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderator | Level | Conditional Indirect Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| −1 SD (−1.3097) | 0.1512 | 0.0447 | 0.0698 | 0.2437 | |

| Self-efficacy | M | 0.1597 | 0.0461 | 0.0762 | 0.2552 |

| +1 SD (1.3097) | 0.1682 | 0.0481 | 0.0811 | 0.2678 | |

| Index of moderated mediation | |||||

| Index | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||

| 0.0068 | 0.004 | 0.0004 | 0.0158 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Jin, X. Exploring the Role of Shared Leadership on Job Performance in IT Industries: Testing the Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16767. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416767

Wang Y, Jin X. Exploring the Role of Shared Leadership on Job Performance in IT Industries: Testing the Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability. 2023; 15(24):16767. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416767

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yu, and Xiu Jin. 2023. "Exploring the Role of Shared Leadership on Job Performance in IT Industries: Testing the Moderated Mediation Model" Sustainability 15, no. 24: 16767. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416767

APA StyleWang, Y., & Jin, X. (2023). Exploring the Role of Shared Leadership on Job Performance in IT Industries: Testing the Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability, 15(24), 16767. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416767