Conceptualising Marine Biodiversity Mainstreaming as an Enabler of Regional Sustainable Blue Growth: The Case of the European Atlantic Area

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Policies and Mechanisms Driving Blue Economic Development in the EU and the Atlantic Area

1.2. The Necessity for Marine Biodiversity Mainstreaming in EU’s Blue Economy Sectoral Policies

2. Materials and Methods

- One point of view is that Blue Economy sectors may harm marine ecosystems in various ways, and this impact must be identified and addressed.

- Another point of view is that a sector may have a positive contribution to marine ecosystems in various ways, and these types of positive impacts must be identified and considered as well.

- In the meantime, marine ecosystems, and the need for protecting them can be seen as elements that block economic development.

- At the same time, these same ecosystems may contribute to economic development for the economic value they produce on their own. Indeed, the marine ecosystem itself can be one of the Blue Economy sectors. This is because all activities that aim at preserving ecosystems and the services that they provide (such as blue carbon sequestration) may form part of an economic sector, as the “Communication on a new approach for a sustainable blue economy in the EU” [4] suggests.

3. Results

3.1. The Position of Marine Biodiversity in Blue Economy Sectoral Policies at the EU Level

3.1.1. Marine and Coastal Tourism Policies

3.1.2. Coastal and Marine Aquaculture Policies

3.1.3. Marine Renewable Energy Policies

3.1.4. Fisheries Policies

3.1.5. Maritime Transport, Including Ports

3.2. The Position of Marine Biodiversity in Blue Economy Sectoral Policies and Initiatives in the Atlantic-Area Countries

3.2.1. Maritime Transport and Ports in UK (Northern Ireland)

3.2.2. Maritime and Coastal Tourism in the Republic of Ireland

3.2.3. Marine and Coastal Aquaculture in Portugal

3.2.4. Marine Renewable Energy in France

3.2.5. Sustainable Fisheries in Spain

4. Discussion: Marine Biodiversity Mainstreaming as a Catalyst for Sustainable Blue Growth in the Atlantic Area

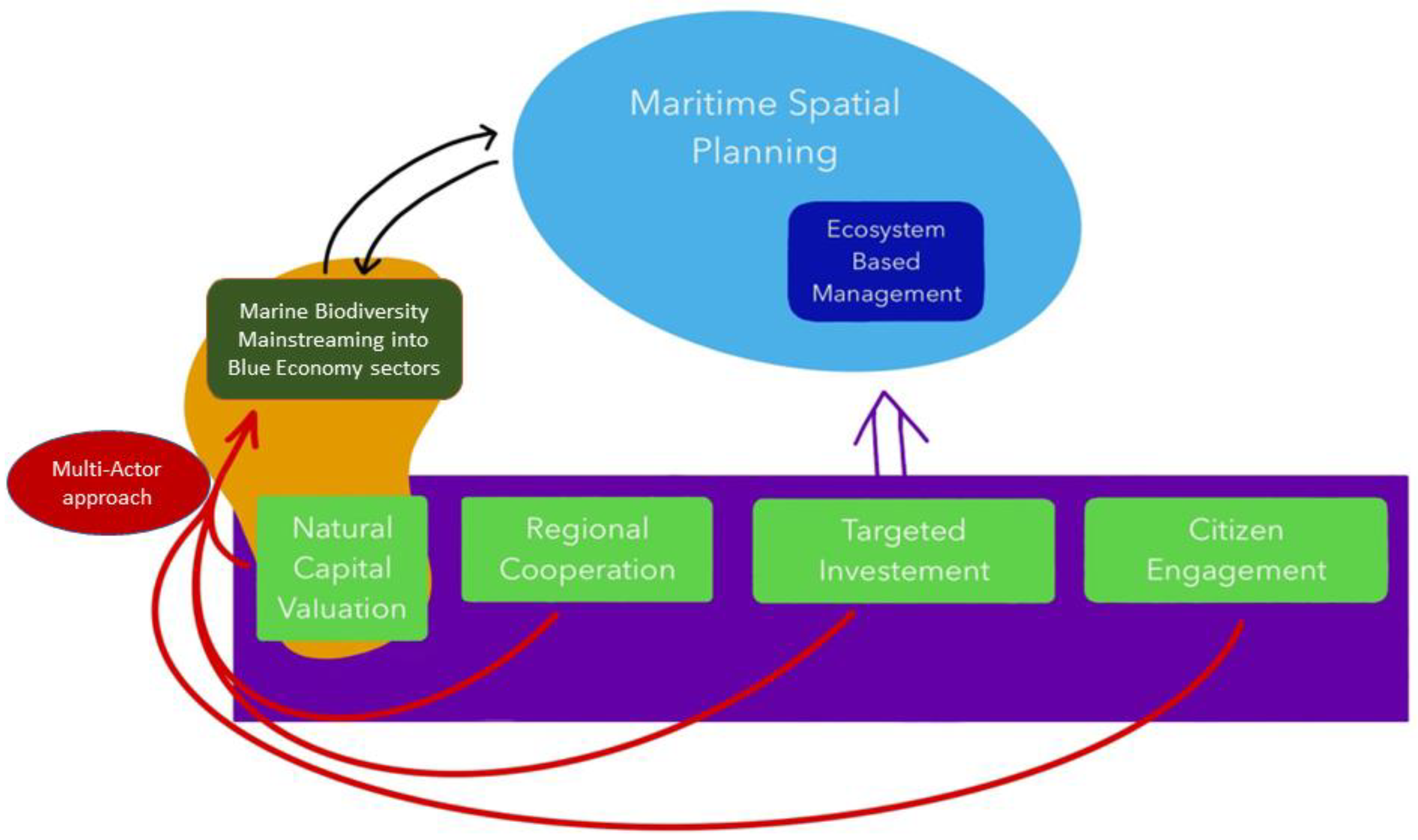

- Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) provides benefits that include reduced sectoral conflicts, a more stable investment environment, and multiple uses of space and environmental protection through the early identification of impacts.

- Ecosystem-Based Management (EBM) requires managers to analyse and address the cumulative impacts of multiple human activities on ecosystems and to understand the resulting transboundary effects as well as medium- and long-term ecosystem changes and their knock-on effects on human wellbeing.

- Natural capital valuation (NCV) can facilitate the mainstreaming of marine biodiversity which in turn is required by EBM and MSP. NCV is necessary to estimate the contribution of ecosystem health to human wellbeing and to assess trade-offs between economic growth and environmental protection. The prioritising of NCV addresses the environmental aspect of SBG.

- Regional cooperation (RC) can create new markets and support the supply of innovation to overcome barriers to either new market entrants or the creation of new market niches for goods and services in the Blue Economy. This action addresses the governance concerns of SBG.

- Targeted investment (TI) and public spending allocated towards forward-thinking ocean research and development can contribute not only to economic growth but also address marine biodiversity loss and climate change. The prioritising of TI addresses the economic concerns of SBG.

- Citizen engagement (CE) and the encouragement of partnerships between practitioners (small and medium-sized enterprises, academia, researchers, public authorities, and investors) are required to co-design and co-implement Sustainable Blue Economy solutions. The prioritising of CE addresses the societal concerns of SBG.

- MBM can be seen as a concept that underpins the implementation of marine management frameworks but that also depends on the same elements (i.e., NCV, RC, TI, and CE) that ensure the effectiveness of these frameworks.

- There is an interdependency between the successfulness of MSP (including EBM) and the successfulness of MBM, as it can be said that one encourages the implementation of the other. MSP is a framework that requires MBM, and MBM is a concept that is linked to actions that need to be part of a broader process involving goals beyond the need for sectors to address environmental issues, a fact that makes MBM an even stronger necessity with a catalytic role. Thus, MBM can be seen as a goal on its own but also a sub-goal of MSP and EBM.

- NCV and the marine ecosystem services valuation within NCV lie at the core of MBM and act as the foundation of MBM. Nevertheless, the concept of ecosystem services was integrated into the European Commission EU Biodiversity Strategy to as a way of mainstreaming biodiversity into other policies, notably agriculture, fisheries, forestry, and regional development. It is apparent that Blue Growth strategies in the Atlantic area would also benefit from NCV and, hence, MBM.

- Such positioning of MBM corresponds to both approaches to policy integration according to Tosun and Lang (2017) [64], i.e., the creation of interdependencies between policy sectors (and consequent coordination between them) and the understanding that policy integration is mostly of a procedural rather than a substantive nature. Also, such positioning addresses the need for cooperation between the involved parts from different policy domains or sectors [64] and is reflected in the horizontal multi-actor approach, as shown in the flowchart. The policy domains can be seen as stable coalitions of involved parties that have shared interests according Trein (2017) [65], and in the suggested flowchart, those can be groups that represent economic, societal, environmental, and governance interests and subsequently the NCV, RC, TI, and SC elements and synergies between them. Finally, it fits well with what Candel and Biesbroek (2016) [66] suggest: that policy integration should be composed of, i.e., a policy frame, subsystem involvement, policy goals, and policy instruments. A policy frame is used to refer to the definition of a dominant problem of societal problems in public policy debates [67]. Policy goals, as the name implies, are the adoption of a specific concern within the policies and strategies of a governance system, including its subsystems, with the goal of addressing this same concern [66]. Policy instruments consist of substantive and/or procedural policy instruments within a governance system (and subsystems) [66]. The substantive instruments assign governing resources of nodality, authority, treasure, and organisation [68] to directly affect “nature types, quantities and distribution of the goods and services provided in society” [66]. The procedural instruments, on the other hand, indirectly affect outcomes through the manipulation of policy processes [69].

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Blue Growth Opportunities for Marine and Maritime Sustainable Growth; 13.9.2012 COM(2012) 494 final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- ECORYS. Blue Growth. Scenarios and Drivers for Sustainable Growth from the Oceans, Seas and Coasts; Final Report; ECORYS Nederland BV.: Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; The European Green Deal/COM/2019/640 final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. On a New Approach for a Sustainable Blue Economy in the EU Transforming the EU’s Blue Economy for a Sustainable Future; COM(2021) 240 final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- EU Sea Basins. 2023. Available online: https://oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu/ocean/sea-basins/eu-sea-basins_en (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- da Silva Marques, I.; Santos, C.; Guerreiro, J. Comparative analysis of National Ocean Strategies of the Atlantic Basin countries. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1001181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Developing a Maritime Strategy for the Atlantic Ocean Area; Com/2011/0782 final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Action Plan for a Maritime Strategy in the Atlantic Area Delivering Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth; COM/2013/0279 final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A New Approach to the Atlantic Maritime Strategy—Atlantic Action Plan 2.0. An Updated Action Plan for a Sustainable, Resilient and Competitive Blue Economy in the European Union Atlantic Area; COM(2020) 329 final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ECORYS. Study on Deepening Understanding of potential Blue Growth in the EU Member States on Europe’s Atlantic Arc; Sea Basin Report; (Client: DG MARE); ECORYS Nederland BV.: Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ertör, I.; Hadjimichael, M. Blue degrowth and the politics of the sea: Rethinking the blue economy. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queffelec, B.; Bonnin, M.; Ferreira, B.; Bertrand, S.; Teles Da Silva, S.; Diouf, F.; Trouillet, B.; Cudennec, A.; Brunel, A.; Billant, O.; et al. Marine spatial planning and the risk of ocean grabbing in the tropical Atlantic. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2021, 78, 1196–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Higgins, T.G.; Lago, M.; DeWitt, T.H. Ecosystem-Based Management, Ecosystem Services and Aquatic Biodiversity: Theory, Tools and Applications; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; p. 580. [Google Scholar]

- Lammerant, J.; Grigg, A.; Dimitrijevic, J.; Leach, K.; Brooks, S.; Burns, A.; Berger, J.; Houdet, J.; Van Oorschot, M.; Goedkoop, M. Assessment of Biodiversity Measurement Approaches for Businesses and Financial Institutions; Update Report 3 on behalf of the EU Business @ Biodiversity Platform; Arcadis: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thushari, G.G.N.; Senevirathna, J.D.M. Plastic pollution in the marine environment. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 Bringing Nature Back into Our Lives; Com/2020/380 Final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, R. Environmental Assessment Report Screening of the Strategic Environmental Assessment Interreg Atlantic Area 2021–2027 Programme. Sociedade Portuguesa de Inovação: SPI on Behalf of the European Union. 2021. Available online: https://light.ccdr-n.pt/index.php?data=a897f81b221255fd3c85e7c9337f0474d5c899506bc2d1cfa885e86b906dbb403f3499d1b1cbfa2f27b5f9bd60659e07 (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Sandström, C.; Ring, I.; Olschewski, R.; Simoncini, R.; Albert, C.; Acar, S.; Adeishvili, M.; Allard, C.; Anker, Y.; Arlettaz, R.; et al. Mainstreaming biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people in Europe and Central Asia: Insights from IPBES for the CBD Post-2020 agenda. Ecosyst. People 2023, 19, 2138553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environmental Agency. EEA Technical report No 5/2005. In Environmental Policy Integration in Europe Administrative Culture and Practices; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lafferty, W.; Hovden, E. Environmental policy integration: Towards an analytical framework. Environ. Politics 2003, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.G. Managing horizontal government. Public Adm. 1998, 76, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, U. Energy and Environment in the European Union: The Challenge of Integration; Ashgate Publishing: Hampshire, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Liberatore, A. The Integration of Sustainable Development Objectives into EU Policy-Making; Routledge: London, UK, 1997; pp. 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A.; Lenschow, A. Environmental policy integration: A state of the art review. Environ. Policy Gov. 2010, 20, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šumrada, T.; Lovec, M.; Juvančič, L.; Rac, I.; Erjavec, E. Fit for the task? Integration of biodiversity policy into the post-2020 Common Agricultural Policy: Illustration on the case of Slovenia. J. Nat. Conserv. 2020, 54, 125804. [Google Scholar]

- Huntley, B.; Petersen, C. Mainstreaming Biodiversity in Production Landscapes; GEF Working Paper 20; Global Environment Facility: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S.; Kok, M.T.; Visseren-Hamakers, I.J.; Termeer, C.J. Mainstreaming biodiversity in economic sectors: An analytical framework. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 210, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinngrebe, Y.M. Mainstreaming across political sectors: Assessing biodiversity policy integration in Peru. Environ. Policy Gov. 2018, 28, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Biodiversity pressure and the driving forces behind. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 61, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazi, Z.; Maes, F.; Rabaut, M.; Vincx, M.; Degraer, S. The integration of nature conservation into the marine spatial planning process. Mar. Policy 2013, 38, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacutan, J.; Galparsoro, I.; Murillas-Maza, A. Towards an understanding of the spatial relationships between natural capital and maritime activities: A Bayesian Belief Network approach. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 40, 101034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillebø, A.I.; Pita, C.; Rodrigues, J.G.; Ramos, S.; Villasante, S. How can marine ecosystem services support the blue growth agenda? Mar. Policy 2017, 81, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, S.; Abentin, E.; Audrey, D.T.; Chen, C.A.; Lim, L.S.; Sitti, R.M.S. Nature-based and technology-based solutions for sustainable blue growth and climate change mitigation in marine biodiversity hotspots. Environ. Biotechnol. 2019, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A European Strategy for More Growth and Jobs in Coastal and Maritime Tourism; COM (2014) 86 final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Tourism and Transport in 2020 and Beyond; COM(2020) 550 final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The N2K Group. Scoping Document on the Management of Tourism and Recreational Activities in Natura 2000. Contract N° 070202/2017/766291/SER/D3. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/natura2000/management/pdf/Scoping_Tourism_Natura2000_final.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Guidelines for the Establishment of the Natura 2000 Network in the Marine Environment. Application of the Habitats and Birds Directives. 2007. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/natura2000/marine/docs/marine_guidelines.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Strategic Guidelines for a More Sustainable and Competitive EU Aquaculture for the Period 2021 to 2030; COM(2021) 236 final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Commission Staff Working Document on the Application of the Water Framework Directive (WFD) and the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) in Relation to Aquaculture; SWD(2016) 178 final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The N2K Group. Guidance on Aquaculture and Natura 2000 Sustainable Aquaculture Activities in the Context of the Natura 2000 Network Environment. Contract N°07.0307/2011/605019/SER/B.3. 2012. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/natura2000/management/docs/Aqua-N2000%20guide.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. An EU Strategy to harness The Potential of Offshore Renewable Energy for a Climate Neutral Future; COM(2020) 741 final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Commission of the European Communities. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Offshore Wind Energy: Action Needed to Deliver on the Energy Policy Objectives for 2020 and Beyond; Com(2008) 768 final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Blue Energy Action Needed to Deliver on the Potential of Ocean Energy in European Seas and Oceans by 2020 and Beyond; COM(2014) 8 final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Le Lièvre, C. Sustainably reconciling offshore renewable energy with Natura 2000 sites: An interim adaptive management framework. Energy Policy 2019, 129, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Commission Notice Guidance Document on Wind Energy Developments and EU Nature Legislation; C(2020) 7730 final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.C. The Protection of Biodiversity in the Framework of the Common Fisheries Policy: What Room for the Shared Competence? In The Future of the Law of the Sea; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union. Council Regulation (EC) No 1005/2008 of 29 September 2008 Establishing a Community System to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing, Amending Regulations (EEC) No 2847/93, (EC) No 1936/2001 and (EC) No 601/2004 and Repealing Regulations (EC) No 1093/94 and (EC) No 1447/1999 (OJ L 286, 29.10.2008, p. 1); Council of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand, L.P.; Neil, A. Bellefontaine. Ocean Governance and Sustainability. Shipp. Oper. Manag. 2017, 231–248. [Google Scholar]

- The N2K Group. Overview of the Potential Interactions and Impacts of Commercial Fishing Methods on Marine Habitats and Species Protected under the EU Habitats Directive. 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/natura2000/marine/docs/Fisheries%20interactions.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- UROPEAN COMMISSION. Commission Staff Working Document on the Establishment of Conservation Measures under the Common Fisheries Policy for Natura 2000 Sites and for Marine Strategy Framework Directive purposes; SWD(2022) 23 final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. Report on Technical and Operational Measures for More Efficient and Cleaner Maritime Transport (2019/2193(ini)); Committee on Transport and Tourism: Strasbourg, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Commission Staff Working Document on the Implementation of the EU Maritime Transport Strategy 2009–2018; SWD(2016) 326 final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. Commission Staff Working Document on Integrating Biodiversity and Nature Protection into Port Development; SEC(2011) 319 final; The Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION. EC Guidance on the Implementation of the EU Nature Legislation in Estuaries and Coastal Zones. 2011. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/natura2000/management/docs/Estuaries-EN.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Kelly, C.; Flannery, W. Blue Growth Pathway for Ports. MOSES. 2020. Available online: http://mosesproject.eu/project_outputs/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Fahy, F.; Carr, L.; Norton, D.; Farrell, D.; Corless, R.; Hynes, S. Blue Growth Pathway for Marine and Coastal Tourism Trail Development. 2020. Available online: http://mosesproject.eu/project_outputs/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Kyriazi, Z.; Marhadour, A. Blue Growth Pathway for Aquaculture. 2020. Available online: http://mosesproject.eu/project_outputs/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- DGPM. Estratégia Nacional para o Mar 2013–2020. 2015. Available online: http://mosesproject.eu/project_outputs/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Kalaydjian, R. Blue Growth Pathway for Offshore Renewable Energy. 2020. Available online: http://mosesproject.eu/project_outputs/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Murillas, A.; Prellezo, R. Blue Growth Pathway for Fisheries. 2020. Available online: http://mosesproject.eu/project_outputs/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Edgar, G.J.; Russ, G.R.; Babcock, R.C. Marine protected areas. Mar. Ecol. 2007, 27, 533–555. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, W.; Jones, P.J. The emerging policy landscape for marine spatial planning in Europe. Mar. Policy 2013, 39, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburto, M.O.; De Los Angeles Carvajal, M.; Barr, B.; Barbier, E.B.; Boesch, D.F.; Boyd, J.; Crowder, L.B.; Cudney-bueno, R.; Essington, T.; Ezcurra, E. Ecosystem-Based Management for the Oceans; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, J.; Lang, A. Policy integration: Mapping the different concepts. Policy Stud. 2017, 38, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trein, P. Coevolution of policy sectors: A comparative analysis of healthcare and public health. Public Adm. 2017, 95, 744–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candel, J.J.; Biesbroek, R. Toward a processual understanding of policy integration. Policy Sci. 2016, 49, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, F.R.; Jones, B.D. Agendas and Instability in American Politics; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, C. The Tools of Government; Chatham House: Chatham, NJ, USA, 1986; pp. 1–978. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, M. Managing the “hollow state”: Procedural policy instruments and modern governance. Can. Public Adm. 2000, 43, 412–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austen, M.C.; Anderson, P.; Armstrong, C.; Döring, R.; Hynes, S.; Levrel, H.; Oinonen, S.; Ressurreição, A. Valuing Marine Ecosystems—Taking into account the value of ecosystem benefits in the Blue Economy. In Future Science Brief; Coopman, J., Heymans, J.J., Kellett, P., Muñiz Piniella, A., French, V., Alexander, B., Eds.; European Marine Board: Ostend, Belgium, 2019; p. 32. ISBN 9789492043696. ISSN 4920-43696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramley, B.; Rogers, A.D.; Hamflett, A.; Turner, J.; Howell, D.; Giannoumis, J.; Matthew, E.; Lambert, N. The Blue Economy in Practice: Raising Lives and Livelihoods; NLA International: Oxford, UK, 2021; 75p. [Google Scholar]

| Reference | Definition |

|---|---|

| European Environmental Agency 2004 [19] | Environmental Policy Integration (EPI) means including environmental considerations in other policies, with a view of achieving sustainable development. |

| Lafferty and Hovden (2003) [20] | “its [EPI] ‘mother concept’—sustainable development—attributed ‘principled priority’ to environmental objectives in the process of ‘balancing’ economic, social and environmental concerns” |

| Peters (1998) [21] | “coordination that emphasizes comprehensiveness, aggregation and especially consistency” |

| Collier (1994) [22] | “the search for synergy effects and ‘win-win’ solutions in the making of sectoral policy choices” |

| Liberatore (1997) [23]; Jordan and Lenschow (2010) [24] | “the notion of reciprocity between equally weighed parties or objectives” |

| Conflicting interactions | Sectoral development causes conflict with marine biodiversity | Marine biodiversity protection may hinder SBG |

| Synergistic interactions | Sectoral developments may have positive impacts on marine ecosystems | Marine biodiversity contributes positively to SBG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kyriazi, Z.; de Almeida, L.R.; Marhadour, A.; Kelly, C.; Flannery, W.; Murillas-Maza, A.; Kalaydjian, R.; Farrell, D.; Carr, L.M.; Norton, D.; et al. Conceptualising Marine Biodiversity Mainstreaming as an Enabler of Regional Sustainable Blue Growth: The Case of the European Atlantic Area. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16762. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416762

Kyriazi Z, de Almeida LR, Marhadour A, Kelly C, Flannery W, Murillas-Maza A, Kalaydjian R, Farrell D, Carr LM, Norton D, et al. Conceptualising Marine Biodiversity Mainstreaming as an Enabler of Regional Sustainable Blue Growth: The Case of the European Atlantic Area. Sustainability. 2023; 15(24):16762. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416762

Chicago/Turabian StyleKyriazi, Zacharoula, Leonor Ribeiro de Almeida, Agnès Marhadour, Christina Kelly, Wesley Flannery, Arantza Murillas-Maza, Régis Kalaydjian, Desiree Farrell, Liam M. Carr, Daniel Norton, and et al. 2023. "Conceptualising Marine Biodiversity Mainstreaming as an Enabler of Regional Sustainable Blue Growth: The Case of the European Atlantic Area" Sustainability 15, no. 24: 16762. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416762

APA StyleKyriazi, Z., de Almeida, L. R., Marhadour, A., Kelly, C., Flannery, W., Murillas-Maza, A., Kalaydjian, R., Farrell, D., Carr, L. M., Norton, D., & Hynes, S. (2023). Conceptualising Marine Biodiversity Mainstreaming as an Enabler of Regional Sustainable Blue Growth: The Case of the European Atlantic Area. Sustainability, 15(24), 16762. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416762