Corporate Decision on Digital Transformation: The Impact of Non-Market Factors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

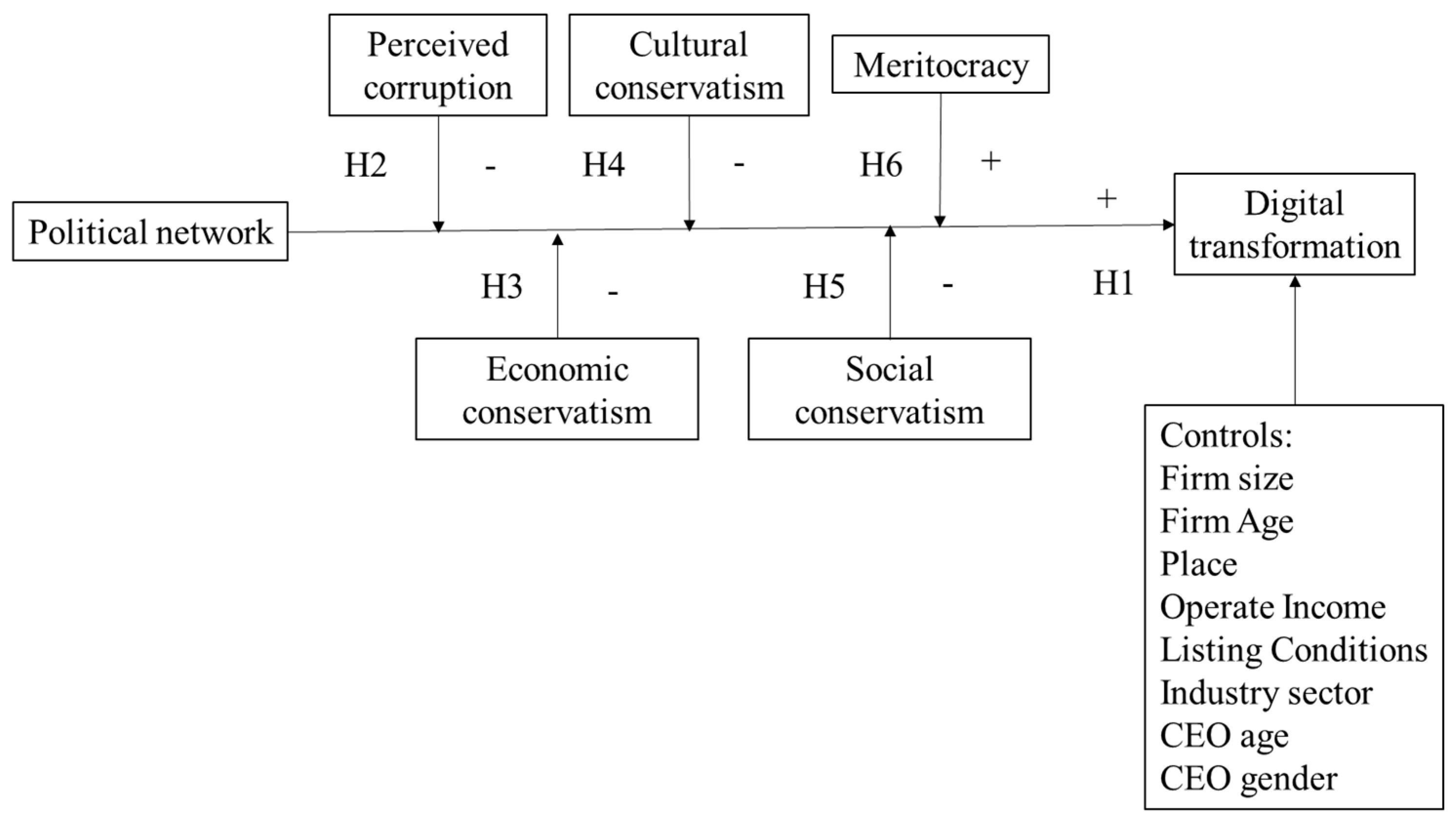

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

2.1. Integrating Coopetition Theory and Political Networks on Digital Transformation Strategy

2.1.1. Coopetition Theory

2.1.2. Public–Private Alliance (PPA) and Digital Transformation

2.2. Engagement in Perceived Corruption as a Moderator of Political Networks and Digital Transformation Relationships: An Institution-Based View

2.3. Engagement in Political Ideology as Moderators of Political Networks and Digital Transformation Relationships: Leveraging Upper Echelons Theory

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Models

3.2. Description of the Population and Sample

4. Results

4.1. Details of the Analysis

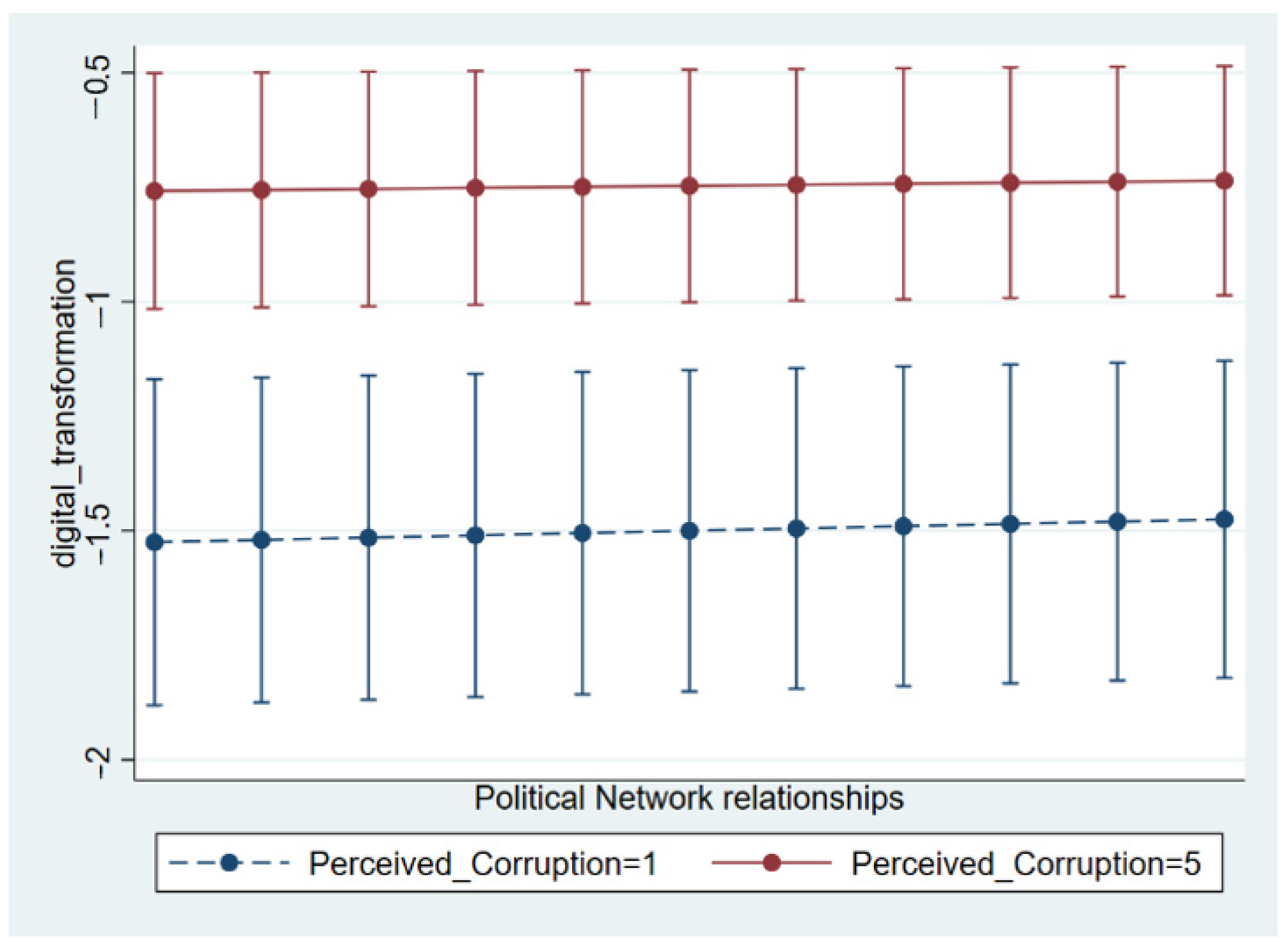

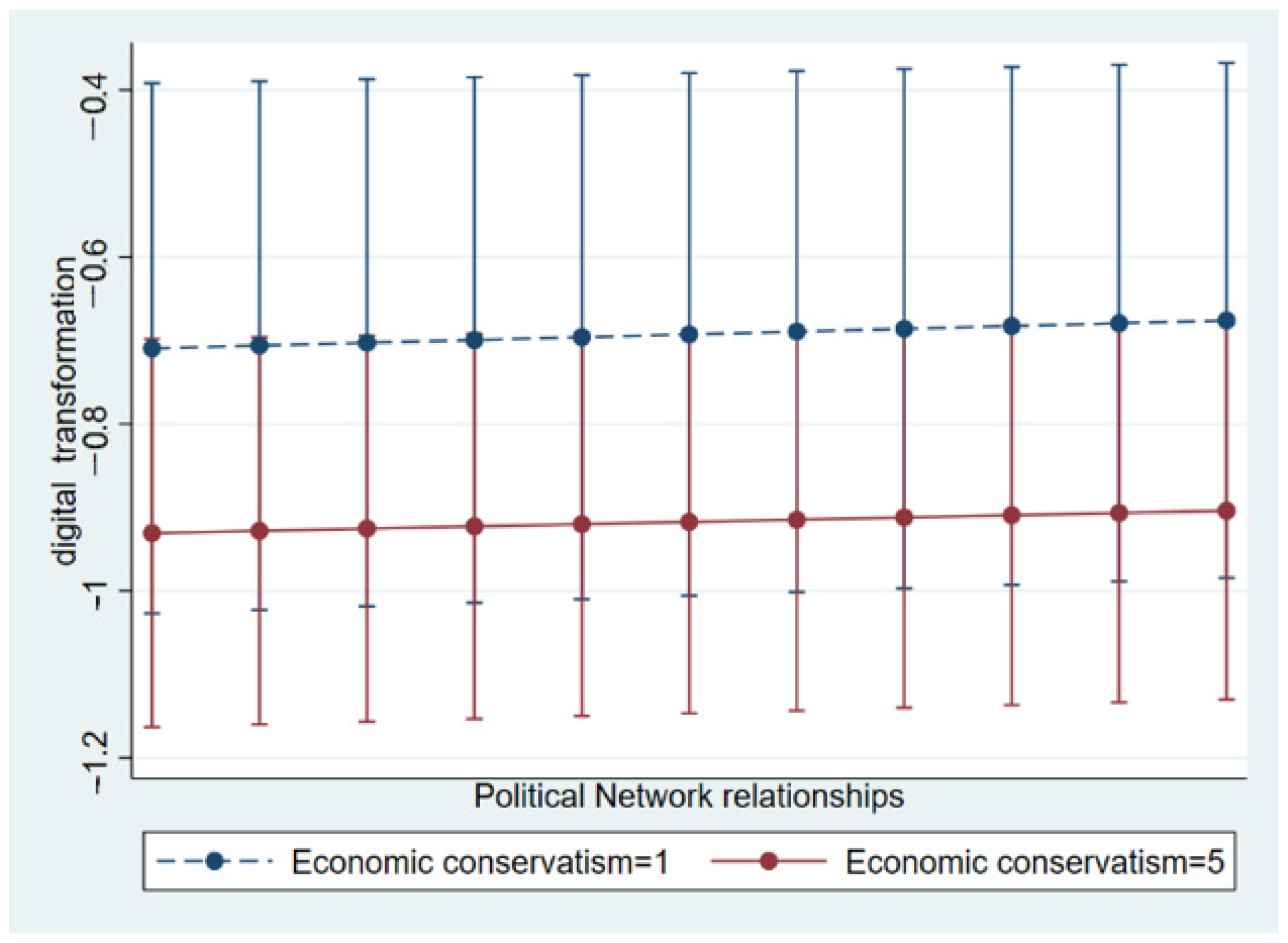

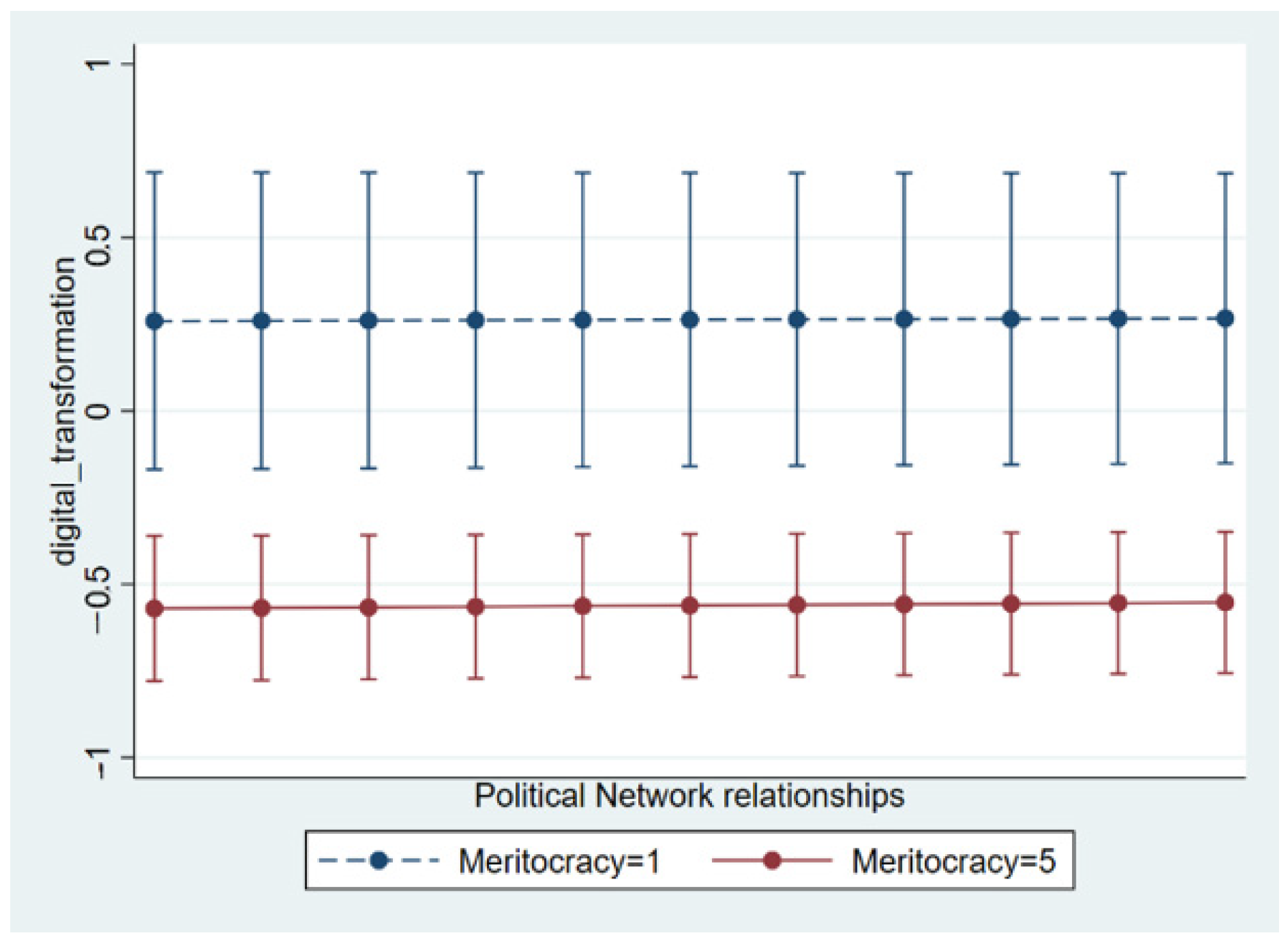

4.2. Details of the Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications for Theory

5.2. Implications for Practice

5.3. Theoretical Results Relate to Practice

5.4. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviations | Items |

| CDO | Chief Digital Officer |

| CEO | Chief executive officer |

| DT | Digital transformation |

| GLS | Generalized Least Squares |

| OLS | Ordinary least squares |

| PPA | Public–private alliance |

| SMEs | Small and medium-sized enterprises |

| TMT | Top management team |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

References

- Dalenogare, L.S.; Benitez, G.B.; Ayala, N.F.; Frank, A.G. The expected contribution of Industry 4.0 technologies for industrial performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 204, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkan, H.; Spohrer, J.C.; Welser, J.J. Digital innovation and strategic transformation. IT Prof. 2016, 18, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElMassah, S.; Mohieldin, M. Digital transformation and localizing the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Ecol. Econ. 2020, 169, 106490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, L. Innovations and Marketing Management of Family Businesses: Results of Empirical Study. Int. J. Entrep. Knowl. 2020, 8, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudose, M.B.; Georgescu, A.; Avasilcai, S. Global Analysis Regarding the Impact of Digital Transformation on Macroeconomic Outcomes. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhironkina, O.; Zhironkin, S. Technological and Intellectual Transition to Mining 4.0: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 1427. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Chen, X.; Dai, W. Effects of Digital Transformation on Environmental Governance of Mining Enterprises: Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarnert, L.V. Population Sorting and Human Capital Accumulation. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2023, 75, 780–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, J.; Mettler, T.; Brenner, W. Using a digital services capability model to assess readiness for the digital consumer. MIS Q. Exec. 2017, 16, 171–195. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian, I.M.; Ross, J.W.; Beath, C.; Mocker, M.; Moloney, K.G.; Fonstad, N.O. How Big Old Companies Navigate Digital Transformation. MIS Q. Exec. 2017, 16, 197–213. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Su, F.; Zhang, W. Digital transformation by SME entrepreneurs: A capability perspective. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 28, 1129–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parakhina, V.N.; Boris, O.A.; Vorontsova, G.V.; Momotova, O.N.; Ustaev, R.M. Priority of public-private partnership models in the conditions of digital transformation of the Russian economic system. Socio-Econ. Syst. Paradig. Future 2021, 314, 837–845. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W.; Zheng, D.; Luo, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. Research of cooperation strategy of government-enterprise digital transformation based on differential game. Open Math. 2022, 20, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xia, J.; Zajac, E.J. On the duality of political and economic stakeholder influence on firm innovation performance: Theory and evidence from Chinese firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittaway, J.J.; Montazemi, A.R. Know-how to lead digital transformation: The case of local governments. Gov. Inf. Q. 2020, 37, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casprini, E.; Palumbo, R. Reaping the benefits of digital transformation through Public-Private Partnership: A service ecosystem view applied to healthcare. Glob. Public Policy Gov. 2022, 2, 453–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Shi, Z.-Z.; Shi, R.-Y.; Chen, N.-J. Enterprise digital transformation and production efficiency: Mechanism analysis and empirical research. Econ. Res. 2022, 35, 2781–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Mardani, A. Does digital transformation improve the firm’s performance? From the perspective of digitalization paradox and managerial myopia. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 163, 113868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W. Political connections and entrepreneurial investment: Evidence from China’s transition economy. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, S.; Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Tarba, S.Y.; Khan, Z. Perceived corruption, business process digitization, and SMEs’ degree of internationalization in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Bus. Res 2021, 123, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ma, G.; Song, X.; Liu, Y. Political connection and business transformation in family firms: Evidence from China. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2016, 7, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, M.; Masulis, R.W.; McConnell, J.J. Political connections and government bailouts. J. Financ. 2006, 61, 2597–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburger, A.M.; Nalebuff, B.J. The right game: Use game theory to shape strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1995, 73, 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Collective rationality and institutional isomorphism in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yami, S.; Castaldo, S.; Dagnino, B.; Le Roy, F. Coopetition: Winning Strategies for the 21st Century; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 325–418. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada, I.; Faems, D.; de Faria, P. Coopetition and product innovation performance: The role of internal knowledge sharing mechanisms and formal knowledge protection mechanisms. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 53, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafezalkotob, A. Competition, cooperation, and coopetition of green supply chains under regulations on energy saving levels. Transp. Res. 2017, 97, 228–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.; Li, J.; Tangpong, C.; Clauss, T. The interplays of coopetition conflicts trust and efficiency process innovation in vertical B2B relationships. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 85, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J. Politicians on the board of directors: Do connections affect the bottom line? J. Manag. 2005, 31, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J. Size and composition of corporate boards of directors: The organization and its environment. Adm. Sci. Q. 1972, 17, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monticelli, J.M.; Verschoore, J.R.; Garrido, I.L. The emergence of coopetition in highly regulated industries: A study on the Brazilian private healthcare market. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2023, 108, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ding, Y. Holistic governance for sustainable public services: Reshaping government–enterprise relationships in China’s digital government context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weritz, P.; Braojos, J.; Matute, J. Exploring the Antecedents of Digital Transformation: Dynamic Capabilities and Digital Culture Aspects to Achieve Digital Maturity. AMCIS 2020 Proc. 2020, 22. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2020/org_transformation_is/org_transformation_is/22 (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Nguyen, S.K.; Vo, X.V.; Vo, T.M.T. Innovative strategies and corporate profitability: The positive resources dependence from political network. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Ribiere, V. Developing a unified definition of digital transformation. Technovation 2021, 102, 102217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Weingast, B.R. Federalism as a commitment to preserving market incentives. J. Econ. Perspect. 1997, 11, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trounstine, J. All politics is local: The reemergence of the study of city politics. Perspect. Politics 2009, 7, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walder, A. Local governments as industrial firms: An organizational analysis of China’s transitional economy. Am. J. Sociol. 1995, 101, 263–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathalikhani, S.; Hafezalkotob, A.; Soltani, R. Government intervention on cooperation, competition, and coopetition of humanitarian supply chains. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 69, 100715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anim-Yeboah, S.; Boateng, R.; Odoom, R. Digital transformation process and the capability and capacity implications for small and medium enterprises. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2020, 10, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwaja, A.I.; Mian, A. Do lenders favor politically connected firms? Rent provision in an emerging financial market. Q. J. Econ. 2005, 120, 1371–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, E.; Rocholl, J.; So, J. Do politically connected boards affect firm value? Rev. Financ. Stud. 2009, 22, 2331–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Meadows, M.; Angwin, D.; Gomes, E.; Child, J. Strategic alliance research in the era of digital transformation: Perspectives on future research. Br. J. Manag. 2020, 31, 589–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmecová, I.; Stuchlý, J.; Sagapova, N.; Tlustý, M. Sme human resources management digitization: Evaluation of the level of digitization and estimation of future developments. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 23, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, R.H.; Hillman, A.J.; Zardkoohi, A.; Cannella, A.A. Former government officials as outside directors: Role of human and social capital. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Knoeber, C.R. Do some outside directors play a political role? J. Law Econ. 2001, 14, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, M.A.L.D.; Vasconcelos, F.C.D.; Goldszmidt, R.G.B. Economic rents and legitimacy: Incorporating elements of organizational analysis institutional theory to the field of business strategy. J. Contemp. Adm. 2007, 11, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakawa, Y.; Peng, M.W.; Deeds, D.L. What drives new ventures to internationalize from emerging to developed economies? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2008, 32, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W.; Sun, S.L.; Pinkham, B.; Chen, H. The institution-based view as a third leg for a strategy tripod. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2009, 23, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elango, B.; Dhandapani, K. Does institutional industry context matter to performance? An extension of the institution-based view. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 115, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meschi, P.X. Government corruption and foreign stakes in international joint ventures in emerging economies. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2009, 26, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R. Why is rent seeking so costly to growth? Am. Econ. Rev. 1993, 83, 409–414. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.J.; Jia, N.; Lu, J. The structure of political institutions and effectiveness of corporate political lobbying. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 158–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capron, I.L.; Chatain, O. Competitors’ resource-oriented strategies: Acting on competitors’ resources through interventions in factor markets and political markets. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Kuper, P.; Choi, Y.H.; Choi, S.J. Does ICT development curb firms’ perceived corruption pressure? The contingent impact of institutional qualities and competitive conditions. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 135, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersema, M.F.; Bantel, K.A. Top management team demography and corporate strategic change. Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Tushman, M.L. Managing strategic contradictions: A top management model for managing innovation streams. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrede, M.; Velamuri, V.K.; Dauth, T. Top managers in the digital age: Exploring the role and practices of top managers in firms’ digital transformation. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2020, 41, 1549–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.A.N.; Simsek, Z.; Lubatkin, M.H.; Veiga, J.F. Transformational leadership’s role in promoting corporate entrepreneurship: Examining the CEO-TMT interface. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, J.; Glaser, J.; Kruglanski, A.; Sulloway, F. Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 339–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jost, J. Ideological asymmetries and the essence of political psychology. Polit. Psychol. 2017, 38, 167–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M.K.; Hambrick, D.C.; Trevi~no, L.K. Political ideologies of CEOs: The influence of executives’ values on corporate social responsibility. Adm. Sci. Q. 2013, 58, 197–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Briscoe, F.; Hambrick, D.C. Evenhandedness in resource allocation: Its relationship with CEO ideology, organizational discretion, and firm performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 1848–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M.K.; Zhang, S.X.; Jahanshahi, A.A.; Nadkarni, S. Unpacking political ideology: CEO social and economic ideologies, strategic decision-making processes, and corporate entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. J. 2021, 64, 1213–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorisdottir, H.; Jost, J.T.; Liviatan, I.; Shrout, P.E. Psychological needs and values underlying left–right political orientation: Cross-national evidence from Eastern and Western Europe. Public Opin. Q. 2007, 71, 175–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hiel, A.; Onraet, E.; De Pauw, S. The relationship between social–cultural attitudes and behavioral measures of cognitivestyle: Ameta-analytic integration of studies. J. Pers. 2010, 78, 1765–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, K.T.; Banti, C.; Instefjord, N. Managerial conservatism and corporate policies. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 68, 101973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malka, A.; Lelkes, Y.; Soto, C.J. Are cultural and economic conservatism positively correlated? A largescale cross-national test. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 2019, 49, 1045–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veselovsky, M.Y.; Izmailova, M.A.; Yunusov, L.A.; Yunusov, I.A. Quality of digital transformation management on the way of formation of innovative economy of Russia. Calitatea 2019, 20, 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, G.C.; Palmer, D.; Phillips, A.N.; Kiron, D.; Buckley, N. Achieving Digital Maturity. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2017, 59, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Imgrund, F.; Fischer, M.; Janiesch, C.; Winkelmann, A. Approaching digitalization with business process management. In Proceedings of the MKWI, Lüneburg, Germany, 6–9 March 2018; pp. 1725–1736. [Google Scholar]

- Deppe, K.D.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Neiman, J.L.; Jacobs, C.; Pahlke, J.; Smith, K.B.; Hibbing, J.R. Reflective liberals and intuitive conservatives: A look at the Cognitive Reflection Test and ideology. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2015, 10, 314–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazachanskaya, E.; Mamychev, A.Y. Conservatism And Conservative Legal Thinking: The Era of Public Systems’ Digital Transformation. In AmurCon 2021: International Scientific Conference, Birobidzhan, Russia, 17 December 2021; Bogachenko, N.G., Ed.; European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences; European Publisher: Crete, Greece, 2022; Volume 126, pp. 446–455. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, S.; Hambrick, D.C.; Cannella, A.A. Strategic Leadership: Theory and Research on Executives, Topmanagement Teams, and Boards; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 157–264. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, M.W.; Luo, Y. Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: The nature of a micro-macro link. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.P.; Rodriguez, P.; Uhlenbruck, K.; Collins, J.; Eden, L. Coping with corruption in foreign markets. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2003, 17, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 236–287. [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj, A.; El Sawy, O.A.; Pavlou, P.A.; Venkatraman, N. Digital Business Strategy: Toward a Next Generation of Insights. MIS Q. Exec. 2013, 37, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustinza, O.F.; Gomes, E.; Vendrell-Herrero, F.; Baines, T. Product–service innovation and performance: The role of collaborative partnerships and R&D intensity. R&D Manag. 2019, 49, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Azarnert, L.V. Transportation costs and the great divergence. Macroecon. Dyn. 2016, 20, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.E. Organizations Evolving; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1979; p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, R.; Surana, M. Neither complements nor substitutes: Examining the case for coalignment of contract-based and relation-based alliance governance mechanisms in coopetition contexts. Long Range Plan. 2022, 55, 102199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Firmographic Category | Frequency | Valid % |

|---|---|---|

| Firm size (employees) | ||

| SMEs | 113 | 52.8% |

| Large companies | 101 | 47.2% |

| Firm age (operating history) | ||

| Strat-ups (less than 42 months) | 29 | 13.6% |

| Firms operating more than 42 months | 185 | 86.4% |

| Place | ||

| Yangtze River Delta region (Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui) | 42 | 19.6% |

| The Pearl River Delta (Guangdong, Hong Kong, Macao) | 26 | 12.1% |

| The Bohai Rim region (Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shandong, Liaoning) | 48 | 22.4% |

| West Triangle Region (Chongqing, Shaanxi, Sichuan) | 25 | 11.7% |

| Middle Yangtze River region (Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi) | 29 | 13.6% |

| Middle Yellow River region (Shanxi, Henan, Inner Mongolia) | 27 | 12.6% |

| Other regions | 17 | 7.9% |

| Listing conditions | ||

| Yes | 21 | 9.8% |

| No | 193 | 90.2% |

| Industry sector | ||

| Manufacturing | 72 | 33.6% |

| Service | 105 | 49.1% |

| Other industries | 37 | 17.3% |

| Firmographic Category | Frequency | Valid % |

|---|---|---|

| CEO gender | ||

| Male | 157 | 73.4% |

| Female | 57 | 26.6% |

| CEO education level (degree) | ||

| Junior high school | 9 | 4.2% |

| Senior high school | 25 | 11.7% |

| Junior college education | 26 | 12.1% |

| Bachelor’s | 87 | 40.7% |

| Master’s | 47 | 22.0% |

| Doctorate | 20 | 9.3% |

| Variable | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital transformation | −2.71 | 1.00 | −2.65 | 2.09 |

| Political network | 3.27 | 1.22 | 1 | 5 |

| Perceived corruption | 3.46 | 1.24 | 1 | 5 |

| Economic conservatism | 3.32 | 1.16 | 1 | 5 |

| Cultural conservatism | 2.32 | 1.11 | 1 | 5 |

| Social conservatism | 3.21 | 0.97 | 1 | 5 |

| Meritocracy | 2.48 | 1.19 | 1 | 5 |

| Factors | Description of Factors | Factor Loading | Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professionals | Enterprise benefits from employee’s specialization in IT and digital knowledge | 0.315 | |

| Flexibility | An adequate degree of organizational flexibility to adapt to changing market conditions | 0.499 | |

| Association | Customers participate in the design and development of new products and services | 0.68 | |

| Digitization | To use IT for process automation, digitization, and data integration | 0.28 | |

| Restructuring | To align technological and business structures | 0.259 | |

| Security | To formulate rules and guidelines for data and information security | 0.531 | |

| Collaboration | To eliminate the obstacles to cross-department cooperation | 0.455 | |

| Culture | Our culture encourages employees to innovate and share knowledge | 0.321 | a = 0.83 |

| Variables | VIF |

|---|---|

| Political network | 1.38 |

| Perceived corruption | 1.23 |

| Economic conservatism | 1.12 |

| Cultural conservatism | 1.21 |

| Social conservatism | 1.29 |

| Meritocracy | 1.43 |

| Firm age (startup or not) | 1.30 |

| Industry | 1.17 |

| Place | 1.24 |

| CEO gender | 1.08 |

| CEO degree | 1.36 |

| Listing conditions | 1.68 |

| Operating income | 2.54 |

| Firm size | 2.79 |

| Variables | Model 1 (Controls) | Model 2 (H1) | Model 3 (H2) | Model 4 ((H3)) | Model 5 (H4) | Model 6 (H5) | Model 7 (H6) | Model 8 (Full Model) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political network | 0.189 *** | 0.520 *** | 0.456 *** | 0.250 *** | 0.281 *** | 0.394 *** | 0.917 *** | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.005) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| Political network X Perceived corruption | −0.094 *** | −0.070 *** | ||||||

| (0.000) | (0.002) | |||||||

| Political network X Economic conservatism | −0.081 *** | −0.067 *** | ||||||

| (0.001) | (0.006) | |||||||

| Political network X Cultural conservatism | −0.027 | −0.032 | ||||||

| (0.266) | (0.192) | |||||||

| Political network X Social conservatism | −0.03 | −0.018 | ||||||

| (0.332) | (0.564) | |||||||

| Political network X Meritocracy | 0.085 *** | 0.056 ** | ||||||

| (0.001) | (0.027) | |||||||

| Perceived corruption | 0.098 *** | 0.083 *** | 0.378 *** | 0.100 *** | 0.086 *** | 0.090 *** | 0.076 *** | 0.323 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.005) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.009) | (0.000) | |

| Economic conservatism | −0.143 *** | −0.171 *** | −0.152 *** | 0.087 | −0.170 *** | −0.168 *** | −0.157 *** | 0.069 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.289) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.400) | |

| Cultural conservatism | −0.024 | −0.02 | 0.002 | −0.022 | 0.065 | −0.019 | −0.006 | 0.104 |

| (0.462) | (0.534) | (0.955) | (0.495) | (0.434) | (0.566) | (0.850) | (0.205) | |

| Social conservatism | 0.187 *** | 0.103 *** | 0.128 *** | 0.109 *** | 0.105 *** | 0.200 * | 0.101 *** | 0.185 * |

| (0.000) | (0.007) | (0.001) | (0.004) | (0.006) | (0.062) | (0.008) | (0.078) | |

| Meritocracy | −0.208 *** | −0.174 *** | −0.164 *** | −0.181 *** | −0.178 *** | −0.173 *** | −0.468 *** | −0.370 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Firm age (startups or not) | 0.021 | −0.087 | −0.127 | −0.109 | −0.089 | −0.071 | −0.108 | −0.144 |

| (0.845) | (0.419) | (0.233) | (0.307) | (0.404) | (0.510) | (0.312) | (0.178) | |

| Industry | −0.207 *** | −0.232 *** | −0.241 *** | −0.215 *** | −0.244 *** | −0.225 *** | −0.239 *** | −0.239 *** |

| (0.007) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.004) | (0.001) | (0.003) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Place | 0.013 | 0.029 | 0.023 | 0.032* | 0.027 | 0.03 | 0.026 | 0.023 |

| (0.514) | (0.131) | (0.222) | (0.090) | (0.161) | (0.118) | (0.174) | (0.213) | |

| CEO gender | −0.039 | −0.025 | 0.034 | 0.019 | −0.034 | −0.033 | −0.022 | 0.043 |

| (0.623) | (0.742) | (0.660) | (0.811) | (0.657) | (0.668) | (0.775) | (0.587) | |

| CEO degree | 0.195 *** | 0.178 *** | 0.161 *** | 0.179 *** | 0.174 *** | 0.181 *** | 0.177 *** | 0.163 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Listing conditions | −0.083 | −0.123 | −0.175 | −0.174 | −0.13 | −0.121 | −0.123 | −0.212 |

| (0.540) | (0.352) | (0.182) | (0.186) | (0.324) | (0.359) | (0.347) | (0.105) | |

| Operate income | 0.116 *** | 0.111 *** | 0.092 *** | 0.101 *** | 0.108 *** | 0.107 *** | 0.098 *** | 0.075 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.006) | |

| Firm size | 0.024 | 0.027 | 0.026 | 0.029 * | 0.028 * | 0.027 | 0.034 ** | 0.035 ** |

| (0.176) | (0.116) | (0.119) | (0.088) | (0.098) | (0.109) | (0.044) | (0.039) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Jimenez, A.; Ordeñana, X.; Choi, S. Corporate Decision on Digital Transformation: The Impact of Non-Market Factors. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416628

Zhang L, Jimenez A, Ordeñana X, Choi S. Corporate Decision on Digital Transformation: The Impact of Non-Market Factors. Sustainability. 2023; 15(24):16628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416628

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Luyao, Alfredo Jimenez, Xavier Ordeñana, and Seongjin Choi. 2023. "Corporate Decision on Digital Transformation: The Impact of Non-Market Factors" Sustainability 15, no. 24: 16628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416628

APA StyleZhang, L., Jimenez, A., Ordeñana, X., & Choi, S. (2023). Corporate Decision on Digital Transformation: The Impact of Non-Market Factors. Sustainability, 15(24), 16628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416628

_Lu.png)